Abstract

The present study examined the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent internalizing symptoms, substance use, and digital media use before and during the pandemic. A nationally representative longitudinal cohort of 3718 Israeli adolescents aged 12–16 at baseline completed measures of internalizing symptoms (anxiety, depression, and somatization), the prevalence of substance use (i.e., previous 30-day use of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis), and average daily use of internet/television, video games, and social media. Social support and daily routines were assessed as potential protective factors for mental health. Data were collected in 10 public schools at four measurement points: before the Covid-19 outbreak (September 2019), after the first wave lockdown (May 2020), after the third wave lockdown (May 2021), and after the fifth wave of the pandemic (May 2022). Multi-level mixed models were used to analyze the longitudinal data. The results showed significant increases in internalizing symptoms, substance use (tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis), and daily screen time from the start of the study to the 33-month follow-up. Social support and daily routines moderated the increases in internalizing symptoms and digital media use. These findings highlight the need for public and educational mental health services to address the continuing impact of the pandemic on adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to constitute a major threat to the mental health of adolescents globally. During adolescence, there is a significant increase in the incidence of internalizing symptoms such as depression, somatization, and anxiety [1]. These emotional difficulties frequently co-occur [2] and can intensify when adolescents face stressful situations, particularly those related to family or health issues [3].

The COVID-19 pandemic produced uncertainty, financial strain, and familial distress, in addition to necessitating social isolation. The enforcement of social distancing, confinement, mass quarantines and school closures significantly impacted adolescents’ lives, since they experienced extended periods of isolation and had limited social contact with their peers. As a result, their physical and social routines were disrupted, leading to a decrease in social support and an increase in social isolation, loneliness, and distress [4]. Since school and peers often constitute sources of support and connection during adolescence, teens were particularly vulnerable to the stress caused by COVID-19-related restrictions and changes [5].

Studies have ascribed significant developmental impairments and psychological symptoms in adolescents to the pandemic period [6]. The literature worldwide has reported wide-ranging psychological reactions ranging from isolated symptoms such as anger, worry, fear and other externalizing behaviors to high rates of internalizing symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic symptoms [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Other studies have indicated that the lengthy periods of quarantine and isolation led to greater use of psychoactive substances in adolescents, including illicit drugs, alcohol, and tobacco [14,15,16,17,18]. Reports also indicate a generalized increase in adolescents’ use of digital technologies and social media in particular to alleviate the negative effects of social distancing during the pandemic [19]. A study involving 5,114 adolescents from five countries showed that over 40% increased their social media consumption to maintain social relations in the absence of in-person interactions [20]. Another study that examined the use of digital technology in 1,860 Italian adolescents found that they spent over six hours a day on screen for educational purposes and from four to six hours a day on recreational activities [21]. Similarly, a study on Australian adolescents reported an increase in social media, internet, and smartphone use along with a decrease in happiness [22].

The excessive use of screen devices has been associated with mental health symptoms such as anxiety and depression [23, 24], and has been associated with addictive behaviors such as alcohol consumption and smoking in adolescents [25]. It has been suggested that these increases can be linked to pandemic-related distress and pressures [26, 27].

The current literature consists primarily of cross-sectional investigations. Today, however, as the pandemic recedes, attempts evaluate the severity of pandemic experiences need to take the dynamic and cumulative nature of this stressful period into account. Exposure to the pandemic cannot be appraised as an isolated singular event or even as a set of discrete events since exposure and responses to earlier pandemic-related events can impact responses to later waves, lockdowns, and the return to ‘normalcy’. An analysis of longitudinal exposure can thus shed light on the potential associations between the COVID-19 pandemic and more long-term psychological outcomes in children and adolescents.

The few longitudinal findings to date suggest that anxiety and depression symptoms tended to increase in adolescents during the pandemic [28,29,30]. Screen use was also found to increase in this age group [31, 32], although some studies have reported lower levels of anxiety and depression and fewer symptoms of social media addiction during the pandemic [33, 34].

Studies on adolescents' substance use during the pandemic have also yielded mixed results. For instance, one study in Italy reported a sharp rise in emergency room treatment for alcohol abuse in adolescents after a strict lockdown [35]. Conversely, a study in Canada found that there was minimal change in substance use throughout the pandemic period [36]. A different Canadian study indicated that substance use declined across clinical and community samples [37]. Yet another Canadian study found that while the proportion of substance users decreased for most substances, the frequency of alcohol and cannabis use increased in adolescents during periods of social distancing [38].

This brief overview suggests that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent mental health, substance use, and screen time depends to a great extent on individual and contextual factors. Nevertheless, most of these analyses are based on short-term assessments without pre-pandemic evaluations, thus making it difficult to determine the specific impact of the pandemic. Although a number of studies have focused on mental health symptoms, only a handful have explored substance use and screen time.

To address these gaps, the current study took advantage of an ongoing pre-pandemic assessment and followed the same cohort over three school years. It is thus uniquely positioned to assess changes in adolescent mental health, substance use, and digital media use during the phases of the pandemic, and can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the pandemic's impact on young people’s mental health.

Relatively few studies have examined the protective factors that may contribute to reducing internalizing symptoms and substance and screen abuse in adolescents during the pandemic. For example, social support is known to buffer reactions to stressful events and help mitigate the severity of psychological symptoms [39]. Previous research has indicated that the presence of significant adults and peers who provide emotional support can reduce negative mental health outcomes in the context of mass disasters and pandemics [40, 41]. Studies have found that social support during the COVID-19 pandemic indeed reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents [42] as well as alcohol use in college students [43]. However, these studies were conducted within a limited time frame during the pandemic, hence, more longitudinal studies with a focus on adolescents are needed.

Consistent everyday routines are also known to shield children and adolescents in times of stress and are crucial to a sense of stability, predictability, and better mental health [44, 45]. Studies have shown that during the home confinements, children engaged in less physical activity, had irregular sleep patterns, and spent more time on digital devices [46]. These effects were aggravated by restrictions on afterschool activities, organized sports, and recreational spaces [15]. By contrast, adolescents who maintained regular routines during the pandemic, including good hygiene, sleep, diet, and study habits experienced less anxiety, conduct problems, and inattention/hyperactivity [47, 48].

The present longitudinal study examined the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on internalizing symptoms, substance, and digital media use in adolescents in Israel over a period of three school years with a baseline measurement before the outbreak of the pandemic. This three-year period included three lengthy lockdowns, numerous school closures/re-openings and remote learning, followed by a relatively more stable period of return to routine in the last year of the study, thus reflecting the unpredictable, rapidly fluctuating conditions of the pandemic. It also examined key potential protective factors in the literature (social support and daily routines) to assess their contribution to adolescents’ ability to cope with this crisis.

The pandemic in Israel had five waves, each with different country-wide lockdown regulations and effects on daily life. The first wave (February 2020–May 2020) involved an abrupt nationwide lockdown, where schools and non-essential businesses were closed, and classes were taught remotely. The regulations for the second wave (June 2020–October 2020) involved hybrid model of in-person classes on a rotating basis in middle schools and high schools. However, restrictions were reinstated when the caseload rose. The third wave (December 2020–March 2021) brought about a return to remote learning and another nationwide lockdown. The Israeli government launched its first vaccination campaign during this wave, and prioritized teachers and students. The fourth (June 2021–October 2021) and fifth waves (December 2021–April 2022) were marked by a high number of cases and hospitalizations among the unvaccinated. To curb the spread of the virus, the government implemented a Green Pass system requiring proof of vaccination or a negative COVID-19 test to enter designated buildings and for public events. Nevertheless, this period was more stable since schools reopened and resumed their regular routines.

Based on the literature, hypothesis 1 posited that the pandemic would lead to increases in psychological distress and internalizing symptoms, as well as more substance and digital media use in comparison to pre-COVID-19 levels. Hypothesis 2 predicted that structured daily routines and social support would moderate the increase in internalizing symptoms, substance and screen use during the pandemic.

Method

Participants and procedure

The sample was composed of 3718 eighth to tenth grade students aged 12.8 to 16.5 (1,865 boys and 1,853 girls; mean age = 14.51, SD = 1.11) at the start of the study from 10 schools from three representative geographic regions in Israel. The procedure involved selecting 10 schools out of a pool of 45 in three representative geographic regions in Israel using a stratified random sampling technique. The initial pool of schools was recruited through municipal education departments and were representative of the general population. The schools were stratified by geographic region, socio-economic distribution, and school type (high school/middle school), and then randomly selected to ensure representation from each stratum. The selection was based on a computer-generated random number list. Special education and ultra-orthodox religious institutions were not included in this study.

After receiving academic and municipal ethics committee authorizations, the parents of all eighth to tenth grade students in these schools received a letter explaining the study. A total of 231 students whose parents opted out of participation (5%) were excluded. All other students who were in school on the day of the baseline assessment (3860 students) were eligible and were asked to provide their written consent to participate. At baseline, 38 students declined to participate. In addition, 104 surveys were removed because of incomplete data. The final sample was thus composed of 3718 students who completed the baseline survey. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The students were guaranteed anonymity and their questionnaires were identified solely by code number.

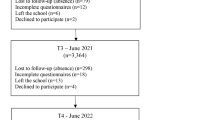

The school year in Israel typically begins in September and ends in mid-June for secondary schools. The participants in this study completed the questionnaires at four different time points: before the COVID-19 outbreak, at the beginning of the school year in September 2019 (N = 3718), after the first wave lockdown in May 2020 (9-month follow-up; N = 3385), after the second and third wave lockdowns in May 2021 (21-month follow-up; N = 3473), and after the fourth and fifth waves of the pandemic in May 2022 (33-month follow-up; N = 3526). The measurement points during the pandemic were situated during the back-to-school phases after periods of lockdowns and all took place towards the end of the school year in Israel.

In total, 3526 participants (95%) from the original sample completed 1 or more follow-up surveys. Over the course of the follow-ups, 71 students left school, 28 students declined to participate, and the others were absent or were excluded because of incomplete data. Participants completed the questionnaires in school on tablets via the Qualtrics application.

There were no statistically significant baseline differences between the participants who dropped out as compared to those who completed the study in terms of demographic characteristics such as age (t = 1.21, p = 0.23), gender (χ2 = 0.01, p = 0.92) family structure (χ2 = 1.22, p = 0.75), and socioeconomic status (χ2 = 2.17, p = 0.34), or the outcome variables, including internalizing symptoms (t = 0.26, p = 0.79), gaming (t = 0.30, p = 0.76), internet use (t = 0.53, p = 0.60), social media (t = 1.58, p = 0.11), and substance use (χ2 = 1.68, p = 0.43).

Measures

The brief symptom inventory [49] (BSI-18) comprises 18 self-report items rated on a five-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). This measure assesses three symptom subscales: somatization, depression, and anxiety. The Global Severity Index (GSI) is calculated as the sum of distress ratings on the 18 items, which can range from 0 to 72, with higher scores indicating greater psychological symptom levels (Derogatis, 2001). The Cronbach's alphas for the total scale ranged from 0.83 to 0.90 across the different measurement points.

The screen time scale [50] examines the daily duration of internet/television, video game, and social media use. The number of hours of use per day in the previous month for each category is reported on a scale ranging from 0 h to more than 7 h. Three scores are derived, one for each category, and the total score for recreational screen time per day.

The adolescent alcohol and drug involvement scale (AADIS) [51] measures history and current substance use. The screening part of the scale examines lifetime use of cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs. If participants report any lifetime substance use, the second 12-item section on specific substance use is completed. The items are rated on an 8-point scale ranging from 0 (never used) to 7 (several times a day). Current substance use is calculated as the percentage of participants who report past 30-day use of each substance category. In this study, only data on the use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, inhalants, and prescription drug misuse were analyzed, given the very low reported numbers of other illicit drug use.

The multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS) [52] measures perceptions of family members and peers as providers of support.

The scale contains eight items and uses a 5-point Likert-type response format that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items are averaged to create a total social support score. The Cronbach's alphas for the scale ranged from 0.82 to 0.87.

The Adolescent Routines Questionnaire (ARQ) [53]. The (ARQ) consists of 20 self-report items that assess daily routines in four domains: hygiene routines, time management, family communication, and extracurricular or social routines. Participants rate how often they engage in these behaviors in a routine manner on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (almost never) to 4 (nearly always). The 20 items are averaged to obtain the total score. The Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.80-0.88 for the total scale.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for the baseline data. For the longitudinal analyses, each change in outcome from pre-COVID-19 to May 2022 was entered into a mixed model growth curve analysis. For the substance use variables, growth curve models with binary outcomes (logistical regressions) were used. Inhalant and prescription drug misuse were not included in the growth models due to their low prevalence.

Trend analyses using SPSS 27.0 indicated that linear trend models had the best fit for the outcome variables. The growth curves modelled the four time points as a linear function of time with the intercept and slope as parameters. The intercept represented the level of the outcome variable at Time 1 and the slope represented the changes in the outcome variable from Time 1 to Time 4. An unstructured variance–covariance matrix was used to allow the variances for the intercept and slope to differ. Full maximum likelihood estimation was used to account for missing data, which totaled less than 3% across the study variables.

The level 1 models examined students' growth trajectories based on the Time variable (0, 1, 2, and 3), perceived social support, daily routines, and their interactions with Time, which captured within-person changes over the different assessments. The level 2 models examined how between-subject variables accounted for the growth parameters in the Level 1 models.

Demographic factors such as age, gender, family structure, and socio-economic status were considered as potential predictors of the outcome variables, given their previous associations with mental health [54, 55] and substance and screen use in adolescents [56, 57]. However, only age and gender were found to significantly contribute to the variability in the outcome scores in this study and were included in the final models.

Based on intraclass correlation analyses, the school effects were below 5% and were not included in the final models. Cohen's d was used to calculate effect sizes for differences in mean scores in the four measurement points. χ2 analyses were conducted to examine differences in substance use over time.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The variables were normally distributed with no unusual skewness or kurtosis. The participants’ summary demographic information and baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The GSI mean score at baseline of 16.26 (SD = 10.94) indicated a mild psychological distress level in the sample at the beginning of the study according to Israeli norms [58]. Prevalence of previous 30-day use of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, inhalants, and prescription drug misuse at baseline were 8.9%, 7.5%, 7.9%, 2.3%, and 1.8% respectively. The mean age at onset of substance use in the sample was 13 years for alcohol and tobacco, and 15 years for cannabis. Boys (n = 167) reported more cannabis use than girls (n = 126) at baseline (χ2 = 5.94; p = 0.01).

At baseline, the participants spent 7 h 25 min a day on average on the internet, video games, and social media. About 56% of the sample spent more than 5 h a day and 40% of the sample spent more than 7 h a day on digital media. Boys spent more time playing video games (M = 1.93 h, SD = 1.80) than girls (M = 1.51 h, SD = 1.76), t(3716) = 7.12, p < 0.001, and girls spent more time on social media (3.01 h, SD = 2.29), t(3716) = 9.34, p < 0.001, and the internet (M = 3.22 h, SD = 2.05), t(3716) = 5.68, p < 0.001) than boys (social media: M = 2.35 h, SD = 2.07; internet: M = 2.84 h, SD = 2.04).

Changes in internalizing symptoms, digital media use, and substance use

The means and standard deviations for the variables at the four time points are reported in Table 2. Tables 3, 4, 5 show the estimated fixed effects for the final models. The ICC ranges were low (0.08–0.17) according to the unconditional mean models, indicating relatively low within-person stability in internalizing symptoms and addictive behaviors during the pandemic, with the majority of the overall variability arising from year-to-year fluctuations in mental health, and substance and digital media use.

The unconditional linear growth curve models of internalizing symptoms, substance use, gaming, and social media use showed significant positive values for the linear slope parameter (time), indicating a positive and significant linear growth rate during each school year. These results indicate that the mean scores of these variables increased significantly over the pandemic period.

Participants exhibited significant increases in symptoms of depression (B = 0.37, SE = 0.05; p < 0.001), anxiety (B = 0.19, SE = 0.05; p < 0.001), somatization (B = 0.26, SE = 0.05; p < 0.001), and general distress (B = 0.82, SE = 0.12; p < 0.001) from the beginning to the end of the study (see Table 3 for CIs). The effect sizes for these changes were relatively small (Cohen's ds = 0.08–0.29).

During the study period, the average daily use of video games increased from 1.72 to 2.81 h per day, and the total daily screen use increased from 7 h 25 min to 8 h 32 min. The effect sizes were small to moderate (Cohen's ds = 0.26–0.55). At the end of the study, 75% of the sample spent more than 5 h a day and 55% of the sample spent more than 7 h a day on digital media.

Prevalence rates of past 30-day tobacco use increased from the baseline level of 7.5% to 11.5% at the end of the study (χ2 = 34.29; p < 0.001). Alcohol use increased from 8.9% at baseline to 17.6% at the end point (χ2 = 119.37; p < 0.001), and cannabis use increased from 7.9% at baseline to 11.9% at the end of the study (χ2 = 34.91; p < 0.001). In contrast, inhalant use declined from 2.3% at baseline to 1% at the end point (χ2 = 21.03; p < 0.001), while prescription drug misuse showed no significant change from 1.8% at baseline to 1.4% at the end of the study (χ2 = 2.01; p = 0.16). Students who reported greater structured and consistent daily routines during the pandemic reported significantly lower increases in depression, anxiety, somatization symptoms, and digital media use. However, daily routines had relatively little effect on reducing the relationship between time and tobacco smoking trajectories. Social support emerged as a significant moderator of mental health symptoms and changes in digital media use.

Adding gender and age to the models yielded statistically significant improvements in all the models. Female gender was a significant predictor of greater mental health symptoms, internet and social media use as well as daily screen time during the pandemic, whereas male gender was a significant predictor of tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use. The significant gender × time interaction indicated that girls experienced a greater increase over the study period than boys in depressive anxiety, and somatization symptoms, and in general distress as reflected in the GSI.

Age was a significant predictor of substance use, daily screen time, and mental health. The findings indicated age increases in cigarette, alcohol, cannabis and digital media use over the course of the study, with greater increases in cannabis use in the older participants and in digital media use in the younger participants.

Discussion

The findings indicated a significant increase in overall reported internalizing symptoms, as well as notable rises in digital media usage, and the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis over three academic years in this cohort of Israeli secondary school students. These results are suggestive of the substantial mental health burden experienced by the adolescent population in general during the pandemic.

Trend analyses showed that the longer the pandemic persists, the greater the anxiety, depression, and somatization symptoms and general psychological distress in this cohort. These findings are consistent with the classic dose–response effect characterizing the relationship between the magnitude of a given stressor and an individual’s response [59]. Here, there was an exacerbation of internalizing symptoms over the course of repeated lockdowns, home isolations and quarantines, but also during more routine periods later on in the pandemic.

Adolescent mental health was already a growing concern prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies over the last ten years have attributed mental health problems in adolescents to the impact of increased screen time and social media use on teens’ social life [60]. Israel is no exception; the increase in mental health symptoms has been associated with a concomitant recourse to psychological and psychiatric treatment in the last decade [61]. Thus, the pandemic may have exacerbated pre-existing mental health concerns in Israeli teens.

The pandemic brought about radical changes in daily life that are likely to have affected adolescent mental health. During the first wave, school closures and remote learning resulted in an overnight upheaval in routine and social contacts, which may explain the considerable increase in depression and anxiety symptoms observed at the 9-month follow-up. In the second wave, schools operated on the basis of a hybrid model, but restrictions were soon reintroduced, creating additional stress and uncertainty that may have contributed to the persistently high levels of internalizing symptoms. However, during the third wave, the national vaccination campaign may have reduced the stress and uncertainty associated with school closures, leading to a slight decrease in internalizing symptoms.

When adolescents returned to their routine lives, the stress and anxiety from the pandemic may have been compounded by the stress of returning to school. This may account for the increase in somatization observed on the last measurement point. Long periods of remote learning, restricted contacts with friends, and disruptions in extracurricular activities may have also taken a toll on their mental health. These factors may have led to the accumulation of stress, anxiety, and depression in the adolescents in this study.

The average total scores for the BSI-18 subscales during the pandemic ranged from 4.85 to 9.19, which correspond to very high levels of symptom profiles and psychological distress. These levels far exceed the Israeli norms for the BSI, which range from 2.76 to 5.64 and in general are higher than the British and U.S. norms [49, 58].

Gender differences emerged in the relationships between pandemic exposure and internalizing symptoms. Girls had greater increases in depression, somatization, and general distress scores than boys, whereas boys reported higher substance use. These findings concur with classic empirical findings indicating greater internalizing symptoms among girls and substance use among boys after exposure to stressful events [62]. Together with the internalizing symptoms, the adolescents' use of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis increased significantly during the study period. However, the findings suggest a mixed picture, with a small, non-significant decrease in tobacco and cannabis use during lockdown periods, and a significant increase, especially in alcohol consumption during the back-to-school routine period.

The decline in tobacco and cannabis use after the first wave may be attributed to the lockdown measures that kept adolescents at home, which reduced their exposure to social situations that tend to facilitate substance use. On the other hand, the increase in alcohol use during this period may be due to its greater availability and accessibility for personal or social consumption at home. During the second wave, when schools reopened with a hybrid model and restrictions were reintroduced, reported substance use levels increased. The easing of the lockdowns may have allowed for more social gatherings, while the prolonged period of lockdown may have caused stress and anxiety, leading to an increase in substance use. The increase in substance use during the back-to-school period, during the fourth and fifth waves, may be an indication of the accumulation of mental health symptoms.

The results also showed an increase in non-school-related digital media use from the pre-pandemic period to the end of the study, where adolescents went from an average of 7 h 25 min to an average of 8 h 32 min per day, including 55% who spent more than 7 h a day on digital media. Although it makes sense that adolescents who experience mental health issues, stress, and social isolation may use screen time to withdraw from stressors, connect with their friends, or manage negative feelings, the results indicated that screen use remained persistently elevated during the gradual relaxing of quarantine restrictions and the return to school, suggesting that personal or familial rules and norms for media use changed significantly.

The findings also point to the importance of two key moderating variables that appeared to have a protective or buffering effect on adolescents during the pandemic. Social support from friends and/or caring family members was associated with fewer depressive symptoms and less screen use in this sample. This finding is consistent with research indicating that social support is associated with lower levels of symptoms and addictive behaviors in stressful circumstances [63, 64].

Daily routines were also important. Chronic stress conditions often lead to less regularity and the disruption of usual routines [65]. Consistent daily routines such as waking up and bedtime hours, adequate sleep, healthy eating behaviors and family meals, balanced daily activities such as socializing with friends, doing schoolwork, recreation, sports, and hobbies all moderated the increases in internalizing symptoms, digital media use and tobacco. The results suggest that adolescents who actively engaged in these foundational activities and had nurturing and supporting relationships appeared to be more resilient to the mental health challenges imposed by the pandemic.

Age was significantly related to mental health symptoms and digital media and substance use, with greater symptoms, problematic media use, and substance use increases during the pandemic. Although it is impossible to disentangle the contextual effects of the pandemic from the developmental effects, the steeper increases in internalizing symptoms and addictive behaviors with age highlight the widespread challenges adolescents continue to face in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. In late adolescence, the development of autonomy and expectations of independent functioning and social interaction with peers become dominant. The current findings suggest that the social isolation and the curtailment of freedom of movement affected adolescents' ability to engage in this developmental phase [66].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sensitive nature of this study could have impacted the students' responses and led to underreporting of symptoms and substance use as a result of reporting bias, recall bias, and social desirability. This may also explain the low reporting of illicit hard drug use. Other measures should be considered in the future to provide a more precise estimation of mental health and substance use outcomes. Second, the study was based on self-report questionnaires and should be extended to include multiple informant reports.

In this study, we had no access to data or medical records on psychiatric disorders in the sample, which could have inflated the outcome measures. Future investigations should account for this factor, given the heightened vulnerability of children and teens with pre-existing mental health issues and the increased difficulties of accessing mental health services [67]. Furthermore, we only measured time spent on digital media and did not simultaneously assess internet addiction or problematic internet use. It is worth noting that adolescent quantitative digital media use was increasing annually before the pandemic [60], so that the increase in digital media use observed in this study cannot be solely attributed to the pandemic.

Finally, this study focused on two potential resilience factors: social support and daily routines. However, other potential protective and risk factors may be significant moderators of the internalizing symptoms and addictive behaviors associated with the pandemic, such as loneliness and emotion dysregulation [34], attachment [68], family cohesion and adaptability [69], parent–child relationships [70], income [71], and urban versus rural living area [72]. Further studies should assess the long list of individual, familial, and social factors that can affect the symptoms associated with the pandemic and the prolonged stressful conditions it generated.

Conclusion

The findings have major implications for policies designed to respond to the broader consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescents’ lives. The sharp increases in internalizing symptoms underscore the urgent need for targeted mental health support and interventions for this vulnerable population. It is crucial to acknowledge that these effects can persist far beyond the pandemic itself, thus highlighting the importance of long-term mental health care for adolescents to address and mitigate potential long-lasting consequences.

The observed rises in substance use are concerning, since breaking away from these newly formed habits can be difficult. These findings emphasize the need to implement substance use prevention and intervention programs specifically designed for adolescents. Ongoing monitoring and support are vital to addressing the potential long-term consequences of increased substance use in order to promote healthier choices and behaviors.

The increased reliance on digital media usage during the pandemic points towards the emergence of new norms among adolescents. As digital platforms have become integral to communication, education, and entertainment, their potential impact on adolescents' overall well-being and social development needs further exploration. Efforts should be made to promote responsible and healthy digital media use, by fostering a balanced approach that acknowledges both the benefits and potential risks associated with excessive screen time. This could involve initiatives centered on digital literacy that would educate adolescents and their families about the potential risks and encourage the development of healthy digital habits.

The importance of the protective factors of social support and consistent daily routines found here clearly suggests that adolescents’ mental health and well-being are deeply intertwined with their social environments and daily habits. Investing in fostering supportive relationships, both among peers and caring family members, can offer crucial support to adolescents, by enabling them to better navigate the challenges posed by the pandemic and by promoting resilience during difficult times. Similarly, encouraging consistent daily routines can provide stability, structure, and a sense of normalcy, all of which can positively impact adolescents' mental health.

Given these findings, it is imperative for schools, parents, and healthcare professionals to work together to develop comprehensive strategies to address the multifaceted challenges faced by adolescents during and beyond the pandemic. Enhancing mental health support services, implementing evidence-based substance use prevention programs, and promoting digital literacy and responsible media use are all key components of these strategies.

References

Petersen IT, Lindheim O, LeBeau B, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Lansford JE, Dodge KA (2018) Development of internalizing problems from adolescence to emerging adulthood: Accounting for heterotypic continuity with vertical scaling. Dev Psychol 54:586–599. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000449

Hankin BL, Snyder HR, Gulley LD, Schweizer TH, Bijttebier P, Nelis S et al (2016) Understanding comorbidity among internalizing problems: integrating latent structural models of psychopathology and risk mechanisms. Dev Psychopathol 28:987–1012. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579416000663

McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML (2009) Stressful life events, anxiety sensitivity, and internalizing symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 118:659–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016499

Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, Crawley E (2020) Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 59:1218–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr 174:819–820. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

Samji H, Wu J, Ladak A, Vossen C, Stewart E, Dove N, Long D, Snell G (2022) Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth–a systematic review. Child Adolesc Ment Health 27(2):173–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12501

Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, Huang Y, Miao J, Yang X, Zhu G (2020) An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord 275:112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

Li W, Zhang Y, Wang J, Ozaki A, Wang Q, Chen Y et al (2021) Association of Home Quarantine and Mental Health Among Teenagers in Wuhan, China, During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Pediatr 175(3):313. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5499

O’Sullivan K, Clark S, McGrane A, Rock N, Burke L, Boyle N et al (2021) A qualitative study of child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ireland. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(3):1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031062

Shah S, Kaul A, Shah R, Maddipoti S (2020) Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and lockdown on mental health symptoms in children. Indian Pediatr 58(1):75–76

Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, Marengo L, Krancevich K, Chiyka E et al (2020) The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety 38(2):233–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23120

Ren H, He X, Bian X, Shang X, Liu J (2021) The protective roles of exercise and maintenance of daily living routines for Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 quarantine period. J Adolesc Health 68(1):35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.026

Yue J, Zang X, Le Y, An Y (2020) Anxiety, depression and PTSD among children and their parent during 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in China. Curr Psychol 41(8):5723–5730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01191-4

Amram O, Borah P, Kubsad D, McPherson SM (2021) Media exposure and substance use increase during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(12):6318. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126318

Chaffee BW, Cheng J, Couch ET, Hoeft KS, Halpern-Felsher B (2021) Adolescents’ substance use and physical activity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr 175(7):715–722. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0541

Lundahl LH, Cannoy C (2021) COVID-19 and substance use in adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am 68(5):977–990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2021.05.005

Pigeaud L, de Veld L, van Hoof J, van der Lely N (2021) Acute alcohol intoxication in dutch adolescents before, during, and after the first COVID-19 lockdown. J Adolesc Health 69(6):905–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.038

Villanti AC, LePine SE, Peasley-Miklus C, West JC, Roemhildt M, Williams R et al (2022) COVID-related distress, mental health, and substance use in adolescents and young adults. Child Adolesc Ment Health 27(2):138–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12550

MediaBriefAdmin (2020) KalaGato report: COVID 19 digital impact: a boon for social media? MediaBrief. https://mediabrief.com/kalagato-vocid-19-digital-impact-report-part-1/ Accessed 5 May 2023

Kerekes N, Bador K, Sfendla A, Belaatar M, Mzadi AE, Jovic V et al (2021) Changes in adolescents’ psychosocial functioning and well-being as a consequence of long-term covid-19 restrictions. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:8755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168755

Salzano G, Passanisi S, Pira F, Sorrenti L, La Monica G, Pajno GB et al (2021) Quarantine due to the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of adolescents: the crucial role of technology. Ital J Pediatr 47:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-021-00997-7

Sikorska IM, Lipp N, Wróbel P, Wyra M (2021) Adolescent mental health and activities in the period of social isolation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Adv Psychiatry Neurol/Postępy Psychiatrii i Neurologii 30:79–95. https://doi.org/10.5114/ppn.2021.108472

Chen IH, Chen CY, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Lin CY, Li XD, Tsang HW (2021) Problematic internet-related behaviors mediate the associations between levels of internet engagement and distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 lockdown: A longitudinal structural equation modeling study. J Behav Addict 10:135–148. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00006

Li X, Vanderloo LM, Keown-Stoneman CD, Cost KT, Charach A, Maguire JL et al (2021) Screen use and mental health symptoms in Canadian children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2140875. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40875

Efrati Y, Spada MM (2022) Self-perceived substance and behavioral addictions among Jewish Israeli adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict Behav Rep 15:100431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2022.100431

Hartshorne JK, Huang YT, Lucio Paredes PM, Oppenheimer K, Robbins PT, Velasco MD (2021) Screen time as an index of family distress. Curr Res Behav Sci 2:100023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100023

Seguin D, Kuenzel E, Morton JB, Duerden EG (2021) School’s out: Parenting stress and screen time use in school-age children during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord Rep 6:100217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100217

Bignardi G, Dalmaijer ES, Anwyl-Irvine AL, Smith TA, Siugzdaite R, Uh S, Astle DE (2020) Longitudinal increases in childhood depression symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown. Arch Dis Child 106:791–797. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-320372

Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Otto C, Devine J, Löffler C, Hölling H (2021) Quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: results of a two-wave nationwide population-based study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32:575–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01889-1

Waite P, Pearcey S, Shum A, Raw JAL, Patalay P, Creswell C (2021) How did the mental health symptoms of children and adolescents change over early lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13458

McArthur BA, Racine N, Browne D, McDonald S, Tough S, Madigan S (2021) Recreational screen time before and during COVID-19 in school-aged children. Acta Paediatr 110:2805–2807. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15966

Kor A, Shoshani A (2023) Moderating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s and adolescents’ substance use, digital media use, and mental health: A randomized positive psychology addiction prevention program. Addict Behav 141:107660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107660

Van der Velden PG, Hyland P, Contino C, von Gaudecker H-M, Muffels R, Das M (2021) Anxiety and depression symptoms, the recovery from symptoms, and loneliness before and after the COVID-19 outbreak among the general population: Findings from a Dutch population-based longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 16(1):e0245057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245057

Pace CS, Rogier G, Muzi S (2022) How are the youth? A brief-longitudinal study on symptoms, alexithymia and expressive suppression among Italian adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Psychol 57(6):700–708. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12866

Grigoletto V, Cognigni M, Occhipinti AA, Abbracciavento G, Carrozzi M, Barbi E, Cozzi G (2020) Rebound of severe alcoholic intoxications in adolescents and young adults after COVID-19 lockdown. J Adolesc Health 67(5):727–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.01

Hawke LD, Szatmari P, Cleverley K, Courtney D, Cheung A, Voineskos AN, Henderson J (2021) Youth in a pandemic: a longitudinal examination of youth mental health and substance use concerns during COVID-19. BMJ Open 11(10):e049209. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049209

Hawke LD, Barbic SP, Voineskos A, Szatmari P, Cleverley K, Hayes E, Henderson JL (2020) Impacts of COVID-19 on Youth Mental Health, Substance Use, and Well-being: A Rapid Survey of Clinical and Community Samples. Can J Psychiatry 65:701–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720940562

Dumas TM, Ellis W, Litt DM (2020) What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors. J Adolesc Health 67:354–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.018

Killgore WDS, Taylor EC, Cloonan SA, Dailey NS (2020) Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Res 291:113216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113216

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N et al (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395(10227):912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30460-8

Lynch KB, Geller SR, Schmidt MG (2004) Multi-year evaluation of the effectiveness of a resilience-based prevention program for young children. J Prim Prev 24(3):335–353. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOPP.0000018052.12488.d1

Qi M, Zhou SJ, Guo ZC, Zhang LG, Min HJ, Li XM, Chen JX (2020) The effect of social support on mental health in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Adolesc Health 67(4):514–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.001

Tam CC, Qiao S, Garrett C, Zhang R, Aghaei A, Aggarwal A, Li X (2022) Substance use, psychiatric symptoms, personal mastery, and social support among COVID-19 long haulers: A compensatory model. medRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.23.22282679v1

Evans J, Rodger S (2008) Mealtimes and bedtimes: Windows to family routines and rituals. J Occup Sci 15(2):98–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2008.9686615

Shoshani A, Kor A (2021) The mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents: risk and protective factors. Psychol Trauma. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001188

Jacob L, Tully MA, Barnett Y, Lopez-Sanchez GF, Butler L, Schuch F, López-Bueno R, McDermott D, Firth J, Grabovac I, Yakkundi A (2020) The relationship between physical activity and mental health in a sample of the UK public: a cross-sectional study during the implementation of COVID-19 social distancing measures. Ment Health Phys Act 19:100345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100345

Qi H, Liu R, Chen X, Yuan XF, Li YQ, Huang HH, Zheng Y, Wang G (2020) Prevalence of anxiety and associated factors for Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 74(9):555–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13102

Ezpeleta L, Navarro JB, de la Osa N, Trepat E, Penelo E (2020) Life conditions during COVID-19 lockdown and mental health in Spanish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(19):7327. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197327

Derogatis LR (2001) Brief symptom inventory 18. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

Mark AE, Janssen I (2008) Relationship between screen time and metabolic syndrome in adolescents. J Public Health 30(2):153–160. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdn022

Moberg DP (2003) Screening for alcohol and other drug problems using the Adolescent Alcohol and Drug Involvement Scale (AADIS). Center for Health Policy and Program Evaluation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 52(1):30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Piscitello J, Cummins RN, Kelley ML, Meyer K (2019) Development and initial validation of the adolescent routines questionnaire: parent and self-report. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 41(2):208–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9707-1

Jose PE, Ratcliffe V (2004) Stressor frequency and perceived intensity as predictors of internalizing symptoms: Gender and age differences in adolescence. N Z J Psychol 33:145–154

Hughes EK, Gullone E (2008) Internalizing symptoms and disorders in families of adolescents: a review of family systems literature. Clin Psychol Rev 28(1):92–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.002

Whitesell M, Bachand A, Peel J, Brown M (2013) Familial, social, and individual factors contributing to risk for adolescent substance use. J Addict 2013:579310. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/579310

Odgers CL, Schueller SM, Ito M (2020) Screen time, social media use, and adolescent development. Annu Rev Dev Psychol 2:485–502. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-084815

Canetti L, Shalev AY, De-Nour AK (1994) Israeli adolescents’ norms of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sc 31(1):13–18

Braun-Lewensohn O, Celestin-Westreich S, Celestin LP, Verleye G, Verté D, Ponjaert-Kristoffersen I (2009) Coping styles as moderating the relationships between terrorist attacks and well-being outcomes. J Adolesc 32(3):585–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.003

Twenge JM, Martin GN, Campbell WK (2018) Decreases in psychological well-being among American adolescents after 2012 and links to screen time during the rise of smartphone technology. Emotion 18(6):765–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000403

Berman T (2019) The State of Young Children in Israel- 2019. The Israel National Council for the Child, Jerusalem

Leadbeater BJ, Kuperminc GP, Blatt SJ, Hertzog C (1999) A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Dev Psychol 35(5):1268–1282. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1268

Slone M, Shoshani A (2014) The centrality of the school in a community during war and conflict. In: Pat-Horenczyk R, Brom D, Vogel JM (eds) Helping Children Cope with Trauma. Routledge, pp 180–192

Wang ES, Wang MC (2013) Social support and social interaction ties on internet addiction: Integrating online and offline contexts. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 16(11):843–849. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0557

Lai FT, Chan VK, Li TW, Li X, Hobfoll SE, Lee TM, Hou WK (2022) Disrupted daily routines mediate the socioeconomic gradient of depression amid public health crises: A repeated cross-sectional study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 56(10):1320–1331. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674211051271

Allen JP, Grande L, Tan J, Loeb E (2018) Parent and peer predictors of change in attachment security from adolescence to adulthood. Child Dev 89(4):1120–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12840

Huscsava MM, Scharinger C, Plener PL, Kothgassner OD (2022) ‘The world somehow stopped moving’: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent psychiatric outpatients and the implementation of teletherapy. Child Adolesc Ment Health 27(3):232–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12481

Muzi S, Rogier G, Pace CS (2022) Peer power! Secure peer attachment mediates the effect of parental attachment on depressive withdrawal of teenagers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(7):4068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074068

Li M, Li L, Wu F, Cao Y, Zhang H, Li X, Kong L (2021) Perceived family adaptability and cohesion and depressive symptoms: A comparison of adolescents and parents during COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord 287:255–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.048

Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT (2020) Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol 75(5):631–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660

Li M, Zhou B, Hu B (2022) Relationship between Income and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(15):8944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158944

Henning-Smith C, Meltzer G, Kobayashi LC, Finlay JM (2023) Rural/urban differences in mental health and social well-being among older US adults in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Ment Health 27(3):505–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2022.2060184

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: AS, AK Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: AS, AK Drafting of the manuscript: AS, AK Statistical analysis: AS, AK

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shoshani, A., Kor, A. The longitudinal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescents' internalizing symptoms, substance use, and digital media use. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 1583–1595 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02269-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02269-7