Abstract

Abstract

Therapeutic games represent a promising solution for addressing emotional difficulties in youths. The aim of the present study was to investigate the effectiveness of the REThink game, in helping children and adolescents, to develop psychological resilience. Therefore, 165 children aged between 10 and 16 years were randomly assigned in one of the three groups: 54 participants in the REThink condition, 55 participants in the Rational Emotive Behavior Education condition, and 56 participants in the waitlist condition. Results indicated that the REThink intervention had a significant impact on emotional symptoms (a moderate-effect size, d = 0.46) and on depressive mood (a large-effect size, d = 0.84). Furthermore, REThink had a significant impact on children’s ability to regulate their emotions, with a significant effect on emotional awareness (d = 0.64), and on the ability for emotional control (d = 0.69). In conclusion, the implications of the REThink game are discussed in relationship with resiliency building programs designed for youths.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03308981.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is estimated that a total of 13–20% of children experience a mental disorder in a given year [1]. Failing to prevent mental disorders in children has dire consequences for their later functioning, putting them at increased risk for mental disorders in adulthood [2,3,4,5,6], which are further associated with decreased productivity, increased substance use and injury, and substantial costs to the individual and society [7, 8]. As such, clinical work and research are geared towards developing and testing prevention efforts.

Although evidence-based interventions exist [9], estimates suggest that about 60% of children and adolescents with mental health disorders do not receive the care which they need [10, 11] due to institutional barriers to care, such as adequately trained therapists or available facilities [12, 13], or individual ones, such as stigma associated to receiving mental health care [12, 13]. In this context, offering evidence-based interventions to treat and prevent mental disorders is considered of crucial importance.

Consequently, there is a need to explore more feasible prevention alternatives and increasing access to evidence-based prevention programs for children and adolescents. Recently, one expanding strategy for increasing access to mental health promotion programs is the use of therapeutic games, which have already been investigated as an adjunct to individual and group psychotherapy (i.e., SPARX, Treasure Hunt, PlayMancer) [14, 15]. More so, according to the World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020, more prevention efforts are needed, which should focus on promoting accessible options for the general population, promoting mental health [16, 17] and developing resilience. Although the previous research pinpoints therapeutic games as a promising solution for addressing emotional difficulties, studies also highlight the need for more serious studies to document their efficacy. Thus, there is a need for theory-based effective interventions that can be used in the general population for preventing mental disorders in children and adolescents.

In this context, the REThink game was designed to respond to such concerns, aiming to offer a theory-based prevention tool that can build psychological resilience in children and adolescents from the general population. The REThink game is focused on helping children learn healthy strategies for coping with dysfunctional negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and depression. REThink is based on positive preventive programs derived from Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT [18]) and Rational Emotive Behavior Education (REBE [19]), which focus as mechanisms of change on cultivating rational beliefs to replace specific irrational beliefs, such as Demandingness, Catastrophizing, Frustration Intolerance, and Self/Other/Life-Downing, with their alternative rational beliefs, such as Preferences, Badness, Frustration Tolerance, and Unconditional Self/Other/Life Acceptance. This is done through learning modules that use experiential and educational methods meant to teach children how to identify their thinking, how to change their dysfunctional emotional reactions by restructuring their irrational beliefs, to engage in effective problem-solving and decision-making strategies, and to cultivate positive emotions and social behaviors [20, 21].

The previous meta-analytic studies have showed both REBT and REBE interventions to be efficacious in promoting mental health and preventing emotional disorders, with moderate-to-large effect sizes for reducing dysfunctional emotions and behaviors and irrational beliefs, increasing rational thinking [22,23,24]. Furthermore, REBE has developed and tested specific cognitive and behavioral techniques in an experiential format, to be used in classrooms [25], which makes it a particularly suitable intervention model when designing a therapeutic computer game.

REThink is a therapeutic videogame accessible online, meant to be used as a standalone intervention to promote emotional resilience in children and adolescents [26]. The game includes a main character, RETMAN, derived from other REBT-based therapeutic tools. RETMAN was first introduced at the Albert Ellis Institute in the 1970s as comics’ character [25], and later developed by David [27] and used in therapeutic stories, cartoons, and robotic systems. RETMAN is a superhero that helps children to think rational and have functional emotions.

In the present study, the primary aim was to test the effectiveness of the REThink game, in helping children and adolescents, aged between 10 and 16 years, to develop psychological resilience. We expected that participants in the REThink group will provide significantly better results compared to waitlist (WL) condition and similar results compared to a face-to-face REBE group, regarding (1) improvements in emotional symptoms (e.g., depressive mood), stress, and positive emotions; (2) improvements in emotion-regulation skills (e.g., focused attention and inhibitory control); (3) improvements in general mental health (e.g., conduct problems). In addition, we expected that participants in the REThink group will provide significantly higher levels of satisfaction compared to REBE group.

Methods

Participants

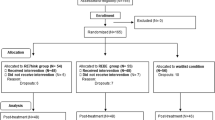

A total number of N=165 healthy children and adolescents, aged between 10 and 16 years, were recruited on a voluntary basis from one middle school located in a small urban community and invited to participate in the present study. Informed consent to participate in the experiment was obtained from their parents and from the school principal. Out of the randomized subjects (N = 56 in the waitlist condition; N = 55 in the REBE condition; N = 54 in the REThink condition; see Fig. 1) 23 (13.94%) did not complete the initial assessment (N = 10–17.86% in the WL condition; N = 7–12.73% in the REBE condition; N = 6–11.11% in the REThink condition). These subjects were thus not introduced in the analysis and were treated as dropouts. No other dropouts were recorded. A Chi-square test comparing the frequency of the dropout in the three groups reported above indicated no statistical differences and excepted distribution due to chance alone, χ2 (2) = 1.14, p =0 .564. The final sample used for data analysis consists of 142 subjects: 46 in the waitlist condition, 48 in the REBE group, and 48 in the REThink group. The mean age of participants was equal to 13.02 (SD = 2.06), 12.75 (SD = 1.95), and 12.93 (SD = 2.20) years old in the REThink group, REBE group, and WL condition, respectively. Sample consisted of 91 girls and 51 boys, with 71.8% of the participants being enrolled in secondary school (grades 5–8) and 28% being enrolled in high school (grades 9 and 10).

The randomization of the participants was done in a stratified manner, with the aim to ensure balance of the treatment groups with respect to the children’s grade. Trial participants were subdivided into seven strata (from the fourth to the tenth grade), and then, permuted block randomization was used for each stratum.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical review board at the institution to which the authors belong. The study protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03308981. One experienced psychologists (certified in CBT/REBT) assisted the REThink intervention and provided intervention in the REBE condition. Two protocols were elaborated for this study, one for each condition (REThink, REBE), including guidelines for intervention in each condition.

Participants in the REThink and REBE groups have completed the seven modules developed for this study. The psychological content of the modules was the same in both groups (see, Fig. 2), the method of delivery being different. In both groups, the application time of a module was approximately 50 min, meetings with students taking place after the classes. If participants from the REThink group did not manage to navigate the module’s levels in 50 min, the experimenter stopped the game and scheduled them to the next module. The delivery time was set at 50 min having as reference that the maximum playing time spent in the respective modules by five children who tested the game before implementing the study. Prior to the first module, children and adolescents completed pre-intervention questionnaires After finalizing module four, children and adolescents completed the mechanisms’ questionnaires. Finally, after finalizing all modules, during 1 month, children and adolescents completed the post-intervention measures. In the REBE group, pre-intervention, intermediate, and post-intervention questionnaires were provided by the psychologists in a group context. In the REThink group, each questionnaire was individually filled in by the participants on the iPad. Questionnaires were displayed before a module (Module 1) or when modules were completed (Modules 4 and 7). Before leaving the experiment room from every module, in both groups, participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation.

The waitlist condition (WL) was assigned to a waiting list and will receive the REThink intervention after the 6-month follow-up assessment, these analyses being reported in another study. WL served as an untreated comparison group during the study, participants taking part only in the three assessment stages during the trial.

Interventions

The REThink game

REThink is a therapeutic online videogame meant to be used as a standalone iOS application to promote emotional resilience in children and adolescents.

The game has seven levels (see, Fig. 3) that take place in different territories on Earth that are under the power of Irrationalizer and need to be conquered back from the bad mind, and at the end of each level, the player has to win the key to go into the next area. Each level has a trial part at the beginning, in which RETMAN is explaining player’s mission, and has various degrees of complexity, which increase as the player progresses.

The scenario of the game and the seven levels structure were developed based on the REBT model, such that it focuses on seven objectives: Level 1: identifying the emotional reactions, and differentiating between basic emotions, complex emotions, and functional and dysfunctional emotions; Level 2: identifying cognitive processes; Level 3: identifying the relation between cognitive processes, emotions, and behavioral reactions; Level 4: changing irrational cognitions into rational cognitions; Level 5: building problem-solving skills; Level 6: building relaxation skills; Level 7: consolidation of the previous skills and building happiness skills (see Fig. 3). For a detailed description of the game, see the supplementary material describing the development of the REThink game (Supplementary material 1).

Participants in the REThink group played twice the seven levels of the game, divided into seven modules (see, Fig. 4). The last module consisted only of applying the level 7 of the game, which is more complex than the others, since it involves practicing all the skills accumulated so far and cultivating positive emotions. Participants played each level on an Apple iPad Air 2.

The REBE group intervention

The REBE group intervention protocol was based on Passport to success curricula [21], using a class lessons format. The objectives of the first group meeting were to teach children emotion awareness and recognition skills, and differentiating between basic emotions, complex emotions, and functional and dysfunctional emotions. At the second meeting, group leader explained to participants what the cognitive processes are and the difference between irrational and rational beliefs. At the third meeting, participants learned to identify the relation between cognitive processes, emotions, and behavioral reactions, using the ABC (DE) model of REBT. During the fourth meeting, children and adolescents used the ABC (DE) model and learned to change irrational cognitions into rational ones. After finalizing session four, children and adolescents completed the mechanism measurement questionnaire. The objective of the fifth meeting was to develop problem-solving skills. The therapist explained, to the participants, the steps of a problem-solving process and provided examples of effective problem-solving. During the sixth meeting, participants learned to practice the abdominal breathing exercise; exercise practiced also in the REThink group (Level 6, see Supplementary material 1). At the final session, therapist with participants reviewed the skills learned in previous meetings and the therapist focused on explaining the positive emotions; the way of their appearance and techniques for the development of positive emotions have been practiced (e.g., the importance of pleasant and new activities).

Measures

Measures

All participants were evaluated before interventions, at the middle of the interventions (only the primary outcome measures and satisfaction levels), and at the time of termination. Primary outcomes were emotional symptoms and depressive mood, and secondary outcomes were emotion-regulation (emotional control, emotional self-awareness), temperamental emotion-regulation features (fear, focused attention, and inhibitory control), functional and dysfunctional negative emotions, positive emotions, and satisfaction levels.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire—child version (SDQ) [28] is a 25-item scale that was used to assess emotional symptoms, as a primary outcome and the total level of psychological difficulties, conduct problems, hyperactivity attention, peer problems, and prosocial behavior, as secondary outcomes. Each item is scored on a three-point Likert-type scale from 0 (“not true”) to 2 (“certainly true”). The score for each of the five scales is generated by summing the scores for the five items that make up that scale, thereby generating a scale score ranging from 0 to 10. The scores for hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, and peer problems can be summed to generate a total difficulties score ranging from 0 to 40; the prosocial score is not incorporated in the reverse direction into the total difficulties score, since the absence of prosocial behaviors is conceptually different from the presence of psychological difficulties. The SDQ demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties in the previous studies [29]. Internal consistency for the current study is α = 0.75 for emotional symptoms subscale, α = 0.80 for the total level of psychological difficulties, α = 0.65 for conduct problems subscale, α = 0.65 for hyperactivity-attention subscale, α = 0.63 for peer problems subscale, and α = 0.67 for prosocial behavior subscale.

The Emotion-Regulation Index for Children and Adolescents (ERICA) [30] was used to assess key aspects of emotion regulation in children and adolescents. In the present study, we used two subscales of the ERICA questionnaire as secondary outcomes: (1) emotional control, for assessing socially appropriate emotional expressions and responses; (2) emotional self-awareness, for assessing emotional recognition and flexibility, upregulation of positive effect and downregulation of negative effect. Participants completed a total number of 13 items on a five-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (“strong disagreement”) to 5 (“strong agreement”). For each subscale, higher scores reflect more adaptive or functional emotion-regulation skills. The measure has been shown to have good psychometric properties in the previous studies [31]. Internal consistency for the current study is α = 0.70 for emotional control subscale and α = 0.57 for emotional self-awareness subscale.

The Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire—Revised (EATQ-R) [32] is designed to measure temperamental effortful control, affiliativeness, surgency, and negative affectivity. The questionnaire contains 65 questions in the self-report form and asks adolescents how true each statement is for them. Response options use a five-point Likert-type scale, from one (“almost always untrue”) to five (“almost always true”). We employed, in the present study, only four subscales from the original questionnaire: (a) depressive mood (primary outcome)—unpleasant affect and lowered mood, loss of enjoyment and interest in activities, (b) attention (secondary outcome)—the capacity to focus attention as well as to shift attention when desired, (c) fear (secondary outcome)—unpleasant affect related to anticipation of distress, and (d) inhibitory control (secondary outcome)—the capacity to plan and to suppress inappropriate responses. For each subscale, we calculated a total score. The subscales were scored, such that a high score indicates that the assessed dimension is high for that individual. The EATQ-R demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in the previous studies [33]. Internal consistency for the current study is α = 0.48 for attention subscale, α = 0.56 for fear subscale, α = 0.52 for inhibitory control subscale, and α = 0.64 for depressive mood subscale.

Functional and Dysfunctional Child Mood Scales—girls and boys versions (FD-CMS; (Gavita, under-review) is composed of nine items based on the binary model of distress [34]. Thus, items on a ten-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (“no emotion”) to 10 (“strong emotion”) assess the intensity of emotions felt by children and adolescents, using images related to the emotions that they feel. The child gives a score to each emotion, depending on the intensity of the last week. Its subscales refer to functional negative emotions (sadness, anxiety, and irritation), dysfunctional negative emotions (depression, fear, and anger) and positive emotions (happiness, trust, and calmness). A high score indicates that the assessed dimension is high for that individual. Internal consistency for the current study is α = 0.80 for functional negative emotions subscale, α = 0.65 for dysfunctional negative emotions subscale, and α = 0.66 for positive emotions subscale.

The Treatment Satisfaction Visual Analogue Scales (TS-VAS) [35] is a self-report visual analogue scale that was used, in the present study, to assess participants’ level of satisfaction with the intervention. Participants were asked at the middle of the intervention and the post-test assessment how satisfied they are with the intervention, on a 10 cm visual analogue scale, with anchors from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very satisfied). Numerous studies validated the use of the VAS with children and adolescents. The VAS has demonstrated good psychometric properties [36].

Power analysis and sample size estimation

The sample size was estimated, so that we can test the efficacy of the REThink intervention by ensuring that we can detect at least a medium-to-large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.60) in a contrast between the REThink and Waitlist conditions at post-test, with a type I error probability of α = 0.05, in a two-tailed test, and a statistical power of at least 0.80. These parameters yielded a sample size of 45 participants per group. Taking into account a dropout rate of up to 20%, power analysis indicated that the require sample size should be of at least 162 participants. The total sample size included in the analysis was in the expected range for the comparison described above.

Statistical analysis

To analyze the results, we first checked for baseline differences between groups using one-way univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Variables that did not show significant differences in baseline measurements were then included in the main analysis, a mixed within-between MANOVA, having the time of measurement (pre-test vs. post-test) as the within-subjects factor, and the groups of treatment (Waitlist vs. REBE vs. REThink) as the between-subjects factor. Only the individual subscales of each measure were included in the MANOVA. We followed significant main effects and the interaction effect with Sidak-adjusted pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal mean, both for within- and between-subjects effects. We computed η 2p as an indicator of effect size for the main and the interaction effects, while, for significant pairwise comparisons, we computed Cohen’s d index of effect size, based on observed means and standard deviations (within-subject ds were adjusted for the correlation between the two measurement times). For measurements that indicated pre-test differences between groups, we computed separated univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs), comparing post-test scores between groups using the pre-test scores as covariates.

To analyze comparatively the satisfaction of participants in the REThink and REBE groups, at the middle of intervention and at post-test, we performed independent-samples t test. We computed the Cohen’s d index as an indicator of effect size [37].

Dropout, missing values, and imputations

Out of the N = 165 randomized subjects (N = 56 in the Waitlist condition; N = 55 in the REBE condition; N = 54 in the REThink condition), 23 (13.94%) did not complete the initial assessment (N = 10–17.86% in the WL condition; N = 7–12.73% in the REBE condition; N = 6–11.11% in the REThink condition). These subjects were thus not introduced in the analysis and were treated as dropouts. No other dropouts were recorded. A Chi-square test comparing the frequency of the dropout in the three groups reported above indicated no statistical differences form and excepted distribution due to chance alone, χ2 (2) = 1.14, p = 0.564.

Two subjects had one missing item each on SDQ behavioral symptoms subscale and FDCMST positive emotions subscale, respectively. The responses to these two items were inputted based on the average responses of the subjects to the items from the same subscales. Because of a data collection error, one subject had missing the pre-test scores for SDQ, EATQ-R, and ERICA instruments. For this subject, the pre-test scores on each subscale of these instruments were imputed based on the average of the group in which he was randomized (REThink) on each individual subscale. The same subject had also missing the values for ERICA instrument at post-test, and the values for the two subscales were inputted using the pre-test values (the average of the group), assuming thus that this subject did not express any change on this measure. No other missing values were identified.

Results

Descriptive statistics for all measures and effect sizes for changes from pre-test to post-test in each group (corrected for the correlation between the two measurement times) are presented in Table 1. One-way Welch robust test for the equality of means (to correct for unequal variances) indicated that the three groups differed at pre-test on two measures, namely SDQ peer-relationship problems, Welch (2, 88.97) = 5.83, p = 0.015, and SDQ prosocial behavior, Welch (2, 87.89) = 5.83, p = 0.004. Games-Howell post hoc test for SDQ peer-relationship problems indicated that REBE group had significantly higher scores than REThink group, p = 0.010, d = 0.61, while, for SDQ prosocial behavior, the same post hoc test indicated that REThink group had significantly higher scores than both Waitlist, p = 0.047, d = 0.50, and REBE, p = 0.009, d = 0.62. Thus, these variables were analyzed in a separate ANCOVA, and were not introduced in the subsequent MANOVA. No other pre-test differences were identified (all ps > 0.05).

For the main analysis (MANOVA), we identified a significant within-subjects main effect (pre-test vs. post-test), Pillai’s Trace = 0.47, F (12, 128) = 9.35, p < 0.001, η 2p = 0.47, but no significant between-subjects main effect (Waitlist vs. REBE vs. REThink), Pillai’s Trace = 0.17, F (24, 258) = 1.02, p = 0.447. The interaction effect was statistically significant, Pillai’s Trace = 0.35, F (24, 258) = 2.27, p = 0.001, and η 2p = 0.17.

Next, we followed the significant multivariate effects with univariate analyses. Time effects can be interpreted directly by looking at the trend in the descriptive statistics, given that there are only two time points when measurements were performed. We found significant univariate time effects for SDQ behavioral symptoms, F (1, 139) = 6.41, p = 0.012, and η 2p = 0.04 (scores have decreased across the three groups); for EATQ-R depressive mood, F (1, 139) = 24.69, p < 0.001, and η 2p = 0.15 (scores have decreased across the three groups); for EATQ-R fear, F (1, 139) = 34.03, p < 0.001, and η 2p = 0.20 (scores have decreased across the three groups); EATQ-R attention, F (1, 139) = 21.09, p < 0.001, and η 2p = 0.13 (scores have increased across the three groups); for EATQ-R inhibitory control, F (1, 139) = 14.16, p < 0.001, and η 2p = 0.09 (scores have increased across the three groups); for ERICA awareness, F (1, 139) = 10.59, p = 0.001, and η 2p = 0.07 (scores have increased across the three groups); for ERICA control, F (1, 139) = 42.70, p < 0.001, and η 2p = 0.24 (scores have increased across the three groups). However, when both time and interaction effects are present for a dependent variable, one should look at the interaction to have a better understanding of the results. All other univariate time effects were not significant (ps > 0.05).

We found significant univariate interaction effects for five dependent variables (see Fig. 5): SDQ emotional symptoms, F (2, 139) = 4.23, p = 0.016, η 2p = 0.06, EATQ-R depressive mood, F (2, 139) = 8.29, p < 0.001, η 2p = 0.11, EATQ-R attention, F (2, 139) = 5.95, p = .003, η 2p = 0.08, ERICA awareness, F (2, 139) = 4.46, p = 0.013, η 2p = 0.06, and ERICA control, F (2, 139) = 10.42, p < 0.001, η 2p = 0.13. All other univariate interaction effects were not significant (ps > 0.05).

Graphical representation for significant interaction effects. Panel a presents the results for SDQ emotional symptoms’ subscale; panel b presents the results for EATQ-R attention subscale; panel c presents the results for EATQ-R depressive mood subscale; panel d presents the results for ERICA awareness subscale; panel e presents results for ERICA control subscale

To understand the interaction effects, we computed both within- and between-subjects pairwise comparisons and generated plots for visual inspection (Fig. 5). The effect on SDQ emotional symptoms was explained by a decrease in scores for REThink group, p = 0.002, d = 0.46, in agreement with our main hypothesis. No other group showed any significant change, and no differences between groups were significant at any time point. The effect on EATQ-R attention was explained by increases in scores in both the REThink, p < 0.001, d = 0.60 and the REBE, p = 0.007, d = 0.47 conditions. Such a trend was not identified in the Waitlist condition, and no significant between-subject differences were found at pre- or post-test. The effect on EATQ-R depressive mood was due to a decrease in scores in the REThink condition, p < 0.001, d = 0.84. Moreover, the REThink group had lower scores at post-test, as compared to the WL group, p = 0.006, d = 0.66. No other significant changes or group differences were present. These results also come as confirmation for our hypothesis related to the efficacy of the REThink game in reducing emotional problems. The interaction effect for ERICA awareness was due to an increase in scores in the REThink condition, p < 0.001, d = 0.65. At post-test, REThink scores were significantly higher than WL scores, p = 0.037, d = 0.49. Finally, for ERICA control, there were improvements (scores have increased) in both REThink, p < 0.001 d = 0.83, and REBE, p = 0.009, d = 0.28, conditions. Again, REThink condition had higher scores compared with WL at post-test, p = 0.032, d = 0.53. The results on ERICA subscales provide additional evidence for the efficacy of the REThink game for emotional outcomes.

Next, we computed univariate ANCOVAs for SDQ peer-relationship problems and prosocial behavior measured ad post-test, having the group of treatment as the independent variable, and the pre-test scores as the covariate. The analyses indicated marginally significant differences between groups for SDQ peer-relationship problems, F (2, 138) = 2.89, p = 0.059, and no significant changes for SDQ prosocial behavior, F (2, 138) = 0.83, p = 0.825.

The comparative analysis yielded significant differences at the middle of intervention between REThink and REBE participants’ satisfaction, t(88) = 2.03, p = 0.045, d = 0.43 (REThink group: M = 8.51, N = 43; REBE group: M = 7.76, N = 47), but no significant post-test differences were observed, t(93) = 1.39, p = 0.166, (REThink group: M = 7.86, N = 47; REBE group: M = 7.36, N = 48).

Discussion

The current study evaluated the newly developed therapeutic game—REThink, which combines evidence-based REBT techniques for mental health prevention with game design principles aimed to build emotional skills in children and adolescents. The primary aim of the RCT was to test the prevention effects of REThink for emotional outcomes in a non-clinical sample of children and adolescents.

Results supported our hypothesis that the REThink intervention will have a significant impact on emotional symptoms. Indeed, children in the REThink group displayed a significant reduction in overall emotional symptoms, with a moderate-effect size (d = 0.46). REBE group and WL group did not show any significant change in overall emotional symptoms, and no differences between groups were significant at any time point. This effect is comparable to that found in a recent meta-analysis of CBT-based selective prevention programs (d = 0.53) and much higher than WL control groups from that same meta-analysis (d = 0.04) [38]. Furthermore, results indicated that children and adolescents in the REThink condition showed a significant decrease in depressive mood, with a large effect size, d = 0.84. The REThink group displayed reduced depressive mood at post-test, as compared to the WL group, d = 0.66. These results confirm our hypothesis that REThink is efficacious for reducing children’s vulnerability to develop emotional problems, both overall and specifically for depressive mood.

We hypothesized that REThink will have a significant impact not only on the children’s emotional wellbeing, but also on their ability to regulate their emotions. This hypothesis was also confirmed. We found a significant effect of REThink on emotional awareness, d = 0.64, and ability for emotional control, d = 0.69. Taken together, these results indicate that REThink is efficacious not only for directly preventing emotional problems in children and adolescents, but also in increasing their emotional awareness and their ability to control and regulate their own emotions, with clear implications for resiliency building.

In addition to the focus on reducing emotional difficulties and increasing emotional regulation, we also wanted to assess whether REThink will have an effect on more stable emotional characteristics. Indeed, we found a significant effect of the intervention for focused attention, with children displaying significantly increased focused attention scores in both REThink intervention, d = 0.60, and in REBE, d = 0.47. While no significant differences were found between REThink and REBE, a similar trend was not present in the WL condition, and no between-subject differences were significant at pre- or post-test.

Furthermore, considering that the REThink game is intended to be a widely accessed intervention by children and adolescents, we analyzed whether the game has this potential, evaluating comparatively the level of satisfaction of REThink’s players and participants in classical, face-to-face intervention. Results indicated that, at the middle of the intervention, participants in the REThink group were more satisfied with the intervention than those in the REBE group, while, in the post-test phase, this effect faded. We expected this difference due to the novelty and the interactive technologies on which the game is build, and this initial increased satisfaction could have potentiated the effect of the REThink game. Alternatively, although, at the end of the interventions, both groups had similar high levels of satisfaction, the mid satisfaction was important for boosting the effects of the game.

Our study was not without limitations. For pragmatic reasons, our intervention was delivered in schools where children were already exposed to REBE-based activities, and it is possible that the lack of significant results for the REBE group were due to that. REBE lessons were part of the monthly activities of the school counselor, and thus, each class participated to them during the past year. Although REThink game was funded on the same REBT principles, the gamified format may have been more attractive to children and this could, at least in part, explain why some results were obtained for REThink and not for REBE. Our satisfaction analyses will help to explain these results. Moreover, future analyses concerning follow-up effects need to establish the long-term effects, since it could be that the lower effects of the REBE face-to-face intervention were due to habituation effects, but it maintains better its effects.

Another limitation was that not all our measures were validated ones. For example, we chose to use Functional and Dysfunctional Child Mood Scales to capture the unique difference between negative functional/dysfunctional and positive emotions experienced by children. However, we obtained, for the subscales, low internal consistency (α = 0.65 for dysfunctional emotions, α = 0.66 for positive emotions) and it is possible that our results were affected by this. Future studies should use validated measures to capture the distinction between functional and dysfunctional emotions.

Overall, the REThink game has proven to be efficacious for reducing youth’s overall emotional problems, and specifically, lowering their depressive mood. More so, results indicate that REThink was efficacious in equipping children with emotional regulation skills (emotional awareness and emotional control), which highlights its role promoting their resilience. Our sample, as results indicate, was a non-clinical sample, which further supports the use of REThink as a prevention effort, to promote resilience in the general, non-clinical population. Future studies should test REThink in a larger public health context, in multiple different schools, as well as in an ecological context (at home, in their routine environments). Future studies should also seek to shed light on the mechanisms of change for REThink, by exploring the potential mediators of this intervention. Given its advantages of scalability, ability to engage children and adolescents, increased access and cost-effectiveness, REThink is a valuable tool in offering accessible and evidence-based prevention strategies for lowering the burden of emotional disorders in youth population.

References

WHO|Child and adolescent mental health. In: WHO. http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/child_adolescent/en/. Accessed 23 Oct 2017

Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2004) The NHSDA report. Availability of illicit drugs among youths. SAMHSA, Rockville, MD

Copeland WE, Miller-Johnson S, Keeler G et al (2007) Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: a prospective, population-based study. Am J Psychiatry 164:1668–1675. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122026

Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A et al (2003) Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:837–844. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837

Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S, Buka S (2006) Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics 118:189–200

Schieve LA, Boulet SL, Kogan MD et al (2011) Parenting aggravation and autism spectrum disorders: 2007 national survey of children’s health. Disabil Health J 4:143–152

Granic I, Lobel A, Engels RC (2014) The benefits of playing video games. Am Psychol 69:66–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034857

Smit F, Cuijpers P, Oostenbrink J et al (2006) Costs of nine common mental disorders: implications for curative and preventive psychiatry. J Ment Health Policy Econ 9:193–200

Weisz JR, Sandler IN, Durlak JA, Anton BS (2005) Promoting and protecting youth mental health through evidence-based prevention and treatment. Am Psychol 60:628–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.628

Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E et al (2003) The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 22:122–133. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.122

Patulny R, Muir K, Powell A et al (2013) Are we reaching them yet? Service access patterns among attendees at the headspace youth mental health initiative. Child Adolesc Ment Health 18:95–102

Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS et al (2014) Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 384:980–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6

Mukolo A, Heflinger CA, Wallston KA (2010) The stigma of childhood mental disorders: a conceptual framework. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2009.10.011

Brezinka V (2008) Treasure Hunt-a serious game to support psychotherapeutic treatment of children. Stud Health Technol Inform 136:71–76

Fernández-Aranda F, Jiménez-Murcia S, Santamaría JJ et al (2012) Video games as a complementary therapy tool in mental disorders: playMancer, a European multicentre study. J Ment Health 21:364–374

Bul KCM, Kato PM, Van der Oord S et al (2016) Behavioral outcome effects of serious gaming as an adjunct to treatment for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 18:e26. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5173

Cheek C, Fleming T, Lucassen MF et al (2015) Integrating health behavior theory and design elements in serious games. JMIR Ment. Health 2:e11. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.4133

Ellis A (1995) Changing rational-emotive therapy (RET) to rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT). J Ration-Emotive Cogn-Behav Ther 13:85–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(195507)11:3<207::aid-jclp2270110302>3.0.co;2-1

Ellis A, Bernard ME (2006) Rational emotive behavioral approaches to childhood disorders. Kluwer Academic\Plenum Publishers, New York

Vernon A (1997) Applications of REBT with children and adolescents. In: Yankura J, Dryden W (eds) Special applications of REBT: a therapist’s casebook. Springer Publishing Co., Inc., New York, pp 11–37

Vernon A (1998) The PASSPORT program: a journey through emotional, social, cognitive, and self-development, grades 9–12. Research Press, Champaign

Gonzalez JE, Nelson JR, Gutkin TB et al (2004) Rational emotive therapy with children and adolescents a meta-analysis. J Emot Behav Disord 12:222–235

Trip S, Vernon A, McMahon J (2007) Effectiveness of rational-emotive education: a meta-analytical study. J Cogn Behav Psychother 7:81–93

David D, Cotet C, Matu S et al (2018) 50 years of rational-emotive and cognitive-behavioral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 74:304–318

Merriefield C, Merriefield R (1979) Call me Ret-man and have a ball. Institute for Rational Living, New York

David OA, Predatu RM, Cardoş R (2018) A pilot study of the REThink online video game applied for coaching emotional understanding in children and adolescents in the therapeutic video game environment: the feeling better resources game. J Evid Based Psychother 18:57–67. https://doi.org/10.24193/jebp.2018.1.5

David D (2010) Retmagia şi minunatele aventuri ale lui Retman. Poveşti raţionale pentru copii şi adolescenţi (Retmagic and the wonderful adventures of Retman. Stories for children and adolescents). RTS Cluj, Cluj-Napoca

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586

Goodman R, Meltzer H, Bailey V (1998) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 7:125–130

Biesecker GE, Easterbrooks MA (2001) Emotion regulation checklist for adolescents. Adapted from shields, AM and Cicchetti D (1997) unpublished manuscript, Tufts University

Hughes EK, Gullone E, Watson SD (2011) Emotional functioning in children and adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 33:335–345

Ellis LK (2002) Individual differences and adolescent psychosocial development. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene

Ellis LK, Rothbart MK (2001) Revision of the early adolescent temperament questionnaire. Poster Present. 2001 Bienn. Meet. Soc. Res. Child Dev. Minneap. Minn

David D, Montgomery GH, Macavei B, Bovbjerg DH (2005) An empirical investigation of Albert Ellis’s binary model of distress. J Clin Psychol 61:499–516

Zecca C, Riccitelli GC, Calabrese P et al (2014) Treatment satisfaction, adherence and behavioral assessment in patients de–escalating from natalizumab to interferon beta. BMC Neurol 14:38

von Baeyer CL (2006) Children’s self-reports of pain intensity: scale selection, limitations and interpretation. Pain Res Manag 11:157–162

Cohen J (1988) The effect size index: d. stat power anal behav sci, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey, pp 20–26

Mychailyszyn MP, Brodman DM, Read KL, Kendall PC (2012) Cognitive-behavioral school-based interventions for anxious and depressed youth: a meta-analysis of outcomes. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 19:129–153. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-2598

Funding

This work was supported by a grant awarded to Oana A. David from the Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research, CNCS—UEFISCDI [Grant Number PN-II-PT-PCCA-2013-4-1937].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

We thank Carmen Pop, Răzvan Predatu, and Mădălina Sucală for their contribution, without which the present study could not have been completed.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

David, O.A., Cardoș, R.A.I. & Matu, S. Is REThink therapeutic game effective in preventing emotional disorders in children and adolescents? Outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28, 111–122 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1192-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1192-2