Abstract

Childhood trauma is a major precipitating factor in psychiatric disease. Emerging data suggest that stress susceptibility is genetically determined, and that risk is mediated by changes in limbic brain circuitry. There is a need to identify markers of disease vulnerability, and it is critical that these markers be investigated in childhood and adolescence, a time when neural networks are particularly malleable and when psychiatric disorders frequently emerge. In this preliminary study, we evaluated whether a common variant in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene (Val66Met; rs6265) interacts with childhood trauma to predict limbic gray matter volume in a sample of 55 youth high in sociodemographic risk. We found trauma-by-BDNF interactions in the right subcallosal area and right hippocampus, wherein BDNF-related gray matter changes were evident in youth without histories of trauma. In youth without trauma exposure, lower hippocampal volume was related to higher symptoms of anxiety. These data provide preliminary evidence for a contribution of a common BDNF gene variant to the neural correlates of childhood trauma among high-risk urban youth. Altered limbic structure in early life may lay the foundation for longer term patterns of neural dysfunction, and hold implications for understanding the psychiatric and psychobiological consequences of traumatic stress on the developing brain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The human brain retains plasticity throughout life. Consequently, experiences have the potential to shape brain organization. Experiences that occur in early life appear to be especially potent in altering the trajectory of neurodevelopment. In particular, early trauma exposure is linked to changes in brain structure and function that persist decades later into adulthood [15]. Moreover, early trauma predicts nearly 45 % of childhood-onset and 30 % of adult-onset psychiatric disorders [33]. Identifying how trauma and stress are biologically embedded in brain organization during formative years has critical implications for lifelong emotional health and well-being [24].

Neurological consequences of trauma and cumulative stress have been studied most extensively in adults. Neuroimaging studies show gray matter volume (GMV) alterations in a number of regions in individuals with histories of early trauma (for a meta-analysis, see [43]). Notably, volumetric reductions are observed in the hippocampus [15, 41] and medial prefrontal cortex [3, 65], limbic brain regions involved in emotion regulation. It is also these regions that show reduced GMV in mood disorders (see [20] for a review). However, studies in adults are limited given that many years, even decades, have often passed since the trauma. As a result, neuroanatomic differences observed in adults may reflect secondary compensatory effects (e.g., brain reorganization in response to trauma) or new environmental exposures (e.g., substance use, stress in adulthood) rather than being the primary result of early traumatic stress.

Childhood trauma likely becomes biologically embedded in the brain during formative, developmental years. We know that many affective disorders originate in childhood and adolescence [52]. Moreover, limbic brain circuitry continues to develop across late childhood and early adolescence [30, 64] and thus may be especially vulnerable to injurious environmental influences. It is essential that neural correlates of traumatic stress be evaluated in children and adolescents (youth) to identify biological markers associated with early trauma that may underpin vulnerability to emotional psychopathology.

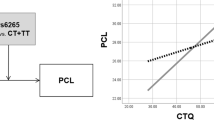

Although childhood trauma strongly predicts the emergence of mood disorders, not all individuals who experience trauma develop clinical conditions. The leading explanation for this disparity is that genetic variability modulates susceptibility to stress. Indeed, prior research provides compelling evidence for gene-by-stress interactions in disease susceptibility [9]. It has been suggested that gene-by-stress interactions explain approximately 60–70 % of variance in vulnerability to affective disorders [35]. Emerging data show that childhood trauma exposure interacts with a common functional variant of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene, consisting of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP; rs6265) in the 5′ prodomain region. This SNP, leading to a valine-to-methionine substitution at codon 66 (Val66Met), is associated with reduced activity-dependent secretion and intracellular trafficking of pro-BDNF, and thus reduced availability of biologically active BDNF. The role of BDNF in the brain is to promote neuronal survival and to aid in neuronal migration, synaptic sprouting, and remodeling [6, 53].

Several lines of research suggest that BDNF genotype interacts with traumatic stress to alter brain anatomy and thereby shift risk for development of emotional psychopathology. The BDNF Met allele has been linked to both anxiety and depressive symptomology, particularly in the presence of traumatic events [1, 40, 67]. Additionally, lower levels of BDNF have been reported in depressed individuals, and this effect is diminished with antidepressant medication (see [34] for a review). Animal studies indicate that early life stress reduces BDNF expression, particularly in BDNF-rich limbic brain regions [22, 27], and these effects persist into adulthood [11]. Human research has shown that healthy [28, 29, 36] and depressed adults [7] that carry the BDNF Met allele and who have histories of early adversity display reductions in subcallosal medial prefrontal and hippocampal GMV. In contrast, increased GMV in the amygdala has been reported in Val/Val homozygotes with histories of early life stress, and for these adults, amygdala GMV additionally predicted higher self-reported anxiety [28]. These observations are consistent with a model in which atypical BDNF function constitutes a risk factor for the development of affective disorders and altered brain limbic structure.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor operates distinctively at different developmental ages [8, 66]. Consequently, a more complex picture emerges when the function of BDNF is considered across development. A study of 4- to 12-year-olds demonstrated that children institutionalized between 0–5 years with the Val/Val genotype had reduced hippocampal GMV, while those with the Val/Met genotype had increased GMV of the amygdala, and that BDNF genotype had no impact on amygdala GMV in the absence of stress [8]. Contradiction between adult and pediatric neuroimaging results suggests that interactions in BDNF genotype, brain anatomy, and traumatic stress may vary for different age groups. Given that type [5] and timing [3] of traumatic exposure influence brain and behavioral outcomes, a second possible explanation for these contrary results is that institutionalization constitutes a specific form of trauma (e.g., early relational deprivation), and thus may predict different results than would other forms of early environmental adversity. The goal of this preliminary study is to begin to address these unknowns by evaluating interactions between BDNF genotype and trauma on limbic GMV in a high sociodemographic risk sample of youth, ages 7–15.

Trauma exposure is extreme among African Americans living in impoverished urban areas [2]. Moreover, African American urban residents are nearly two times more likely to develop psychopathology following trauma [32]. Based on these demographic risk factors, i.e., urban, low income, minority, the present study targeted youth residing in high-risk neighborhoods. We hypothesize that BDNF and trauma will interact to predict GMV of limbic brain regions, including the amygdala, hippocampus, and subcallosal area. In particular, we predict that children with the BDNF Met allele who are exposed to trauma will show larger amygdala volumes, and smaller hippocampal and subcallosal volumes. This is consistent with animal research showing that stress increases BDNF expression and produces dendritic growth in the amygdala, whereas it reduces BDNF expression and causes dendritic shortening in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex (see [47] for a review).

Materials and methods

Participants

55 children and adolescents, ages 7–15, were recruited through classified advertisements placed on Craigslist (Detroit), printed flyers, Wayne State University (WSU) community, and Metro Detroit mental health clinics. Recruitment materials targeted high-risk (urban, minority, low income) neighborhoods and clinics; however, these demographic factors were not considered necessary for study inclusion. Consistent with this, 42 % of study participants were African American and 54 % reported annual incomes <$40,000 (see Table 1). Exclusion criteria included history of neurological injury, significant learning disorder, English as a second language, and presence of MRI contraindications. Prior to the scan session, participants and parents were shown a brief video to prepare them for the MRI scan (http://www.brainnexus.com/links). Symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed using the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCR-C; [4]) and the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI, short version; [42]). Full-Scale IQ was determined using the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (KBIT2; [39]) and pubertal development was assessed using the self-reported Tanner stages questionnaire [45]. Written informed consent and child/adolescent assent was obtained for all participants and their parents as approved by the WSU Institutional Review Board.

BDNF polymorphism genotyping

Genetic analyses were carried out at the WSU Applied Genomics Technology Center. DNA was isolated from saliva collected in Oragene DNA collection tubes using EZ1 Advanced (Qiagen) with standard conditions. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism (rs6265) was investigated using a 5′-nuclease assay (Life Technologies TaqMan assay C_11592758_10). Assays were run in a 5 µl reaction under standard TaqMan conditions on a QuantStudio 12K Flex (Life Technologies). Data were analyzed using Taqman Genotyper software (v.1.3; Life Technologies).

Trauma and BDNF groups

Participants were characterized based on trauma exposure and genotype. Participants who experienced at least one trauma indicated on the Children’s Trauma Assessment Center Screen Checklist were categorized as ‘trauma’. Trauma checklist items are provided in Table 1. In this preliminary study, we were underpowered to dissociate different trauma types. Nonetheless, we excluded three checklist items narrowing trauma to deprivation (e.g., neglect) and victimization or threats to safety (e.g., abuse, violence exposure), distinct [49], but central trauma types. We excluded: exposure to drug activity, parental/caregiver drug use/substance abuse, and frequent and multiple moves or homelessness. Checklist items were reviewed with both parent/caregiver and child in interviews conducted by trained clinical psychology graduate students. 21 of the 55 participants endorsed trauma exposure. BDNF groups consisted of Val/Val homozygotes (n = 46) and Val/Met heterozygotes (‘Met carriers’; n = 9). Consistent with the rarity of the Met allele, no participants possessed a Met/Met genotype. Importantly, genotypic distribution did not differ between trauma and comparison groups, χ 2 = 0.107, p = 0.743 (n = 6 comparison Val/Val), and genetic distribution across the sample was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, χ 2 = 2.475, p = 0.116. African American and Caucasian participants (the largest racial groups) were also in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for their expected genotypic frequencies, χ 2 = 0.045, p = 0.835 and χ 2 = 2.659, p = 0.103, respectively. African American and Caucasian participants did not differ on whole-brain volume or GMV in regions assessed (ps > 0.3).

Trauma and comparison groups were matched on sex and race distribution, age, pubertal stage, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and highest level of parent educational attainment (median for both trauma and comparison groups: 4-year degree; p > 0.1). Average annual income was lower for trauma participants; however, this effect did not reach significance, p = 0.06 (see Table 1). Average IQ was lower for trauma relative to comparison youth (see Table 1), an effect anticipated based on prior work (e.g., [16]). To account for this group difference, we either controlled for IQ in statistical analyses or evaluated effects of BDNF separately within each group, as detailed below. In addition, groups differed on whole-brain volume (mean ± SD; trauma = 1422096.19 ± 141021.1 mm3; comparison = 1343082.65 ± 110538.21 mm3), t(53) = 2.316, p = 0.02. All GMV values were adjusted for whole-brain volume (described below). BDNF groups did not differ on sex or race distribution, age, pubertal stage, IQ, annual household income, anxiety or depressive symptoms, highest level of parent educational attainment, or whole-brain volume (ps > 0.1).

Magnetic resonance imaging data acquisition

Magnetic resonance imaging scanning was conducted at the WSU School of Medicine with a single Siemens 3.0 Tesla system (MAGNETOM Verio, Siemens Medical Solutions) equipped with a 12-channel head coil. High-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images were acquired for each subject. A three-dimensional T1 magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MP-RAGE) sequence was used with the following parameters: TR: 1680 ms, TE: 3.51 ms, orientation: axial, matrix: 384 × 384, 176 slices, flip angle: 90°, voxel size: 0.7 × 0.7 × 1.3 mm.

Structural image processing

Before analysis, T1-weighted anatomical images were screened for motion artifacts (ghosting, blurring). Six participants with scans exhibiting severe artifacts were excluded from the study sample. For remaining participants (N = 55), individual participant whole-brain intracranial masks were generated and manually edited by one rater (N.K.) using the interactive editing tools in the BrainSuite software package (v.13a4; [58]; http://brainsuite.org/). Intrarater reliability was tested by generating whole-brain intracranial masks twice for five brains, at least 2 weeks apart. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; [60]) was computed using the total number of voxels in each brain mask; reliability was confirmed by an ICC measure of >0.90. Whole-brain masks and MR image volumes were then processed using BrainSuite to produce participant-specific models of brain structure and derive total GMV of regions of interest (ROIs) in left and right hemispheres. Three ROIs were selected a priori: subcallosal area, hippocampus, and amygdala, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Computation of ROI GMV was achieved through a semi-automated series of steps implemented within BrainSuite. First, surface mesh models of the inner and outer boundaries of the cerebral cortex were produced using a series of steps, including bias field correction, tissue classification, and topology correction [57, 59]. The surface models, tissue maps, and bias-corrected MR images are then processed with SVReg, a surface and volume registration and labeling module integrated with BrainSuite, which maps the participant data to a reference atlas. SVReg first performs surface-based registration on a mid-cortical surface produced by averaging the inner and outer cortical surface meshes. Participant-specific ROIs are delineated by aligning participant-specific surface maps to the volume atlas; fits for each ROI are refined using geodesic curvature flow [37]. Coregistered cortical surfaces are used as a constraint to generate full volumetric registration using p-harmonic mapping and intensity-based refinement [38]. Data from 0–3 cases per ROI were missing due to artifacts that prohibited automatic segmentation of brain substructures, following manual masking procedures. Because these values were missing at random, whole-sample mean replacement was used.

Group analysis

Total GMV of each ROI (Fig. 1; separately for left and right hemispheres) was computed and adjusted for intracranial volume (cf. [26]). Outliers were Winsorized to two standard deviations above or below the mean. Results are reported on Winsorized data, and were further confirmed with analyses that excluded outliers and missing values. Main effect of BDNF genotype on ROI GMV was evaluated separately within trauma and comparison groups using two-sample t tests. Effects were considered significant at p < 0.0083, Bonferroni corrected for analysis of six ROIs. Significant effects were followed up with analysis of trauma-by-BDNF interaction for that ROI in the full sample (controlling for IQ). Post hoc power analysis suggested an acceptable power level of 0.89 for detecting a reliable group-by-genotype interaction (GPower; [23]). Trauma-by-sex interactions were evaluated in follow-up analyses. Pearson bivariate correlation was used to test for relationships between GMV and symptoms of anxiety; Spearman correlation was used for depressive symptoms given evidence of slight positive skew in CDI scores. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS v.22 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL). Follow-up analyses were considered significant at p < 0.05.

As a validation step, we repeated trauma-by-BDNF GMV interaction analyses in a case–comparison matched subsample. This addresses the presence of more Val/Val than Met participants in the study sample. Met allele carriers were compared to an equal number of Val/Val participants matched in trauma exposure, age, sex, IQ, and race.

Results

Interactive effects of trauma and BDNF genotype on subcallosal and hippocampal gray matter volume

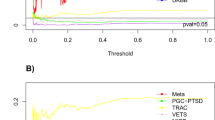

Within comparison youth, GMV of the right subcallosal area, t(32) = 3.08, p = 0.004, and right hippocampus, t(32) = 2.9, p = 0.008, was higher in Met carriers than Val/Val homozygotes (see Figs. 2, 3). Effects of BDNF were not observed within trauma-exposed youth (ts < 0.7, ps > 0.5). Effects of BDNF on amygdala GMV were not significant within trauma-exposed, p = 0.9 (left) and p = 0.97 (right), or comparison groups, p = 0.085 (left) and p = 0.583 (right).

Effects of BDNF genotype on gray matter volume of the right subcallosal area in comparison, but not trauma-exposed youth. Regional values are adjusted for whole-brain volume. Error bars represent standard error. *p < 0.0083 (Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons), within-group t tests. Effect of trauma within gene groups was not tested due to the limited number of Met allele carriers

Effects of BDNF genotype on gray matter volume of the right hippocampus in comparison, but not trauma-exposed youth. Regional values are adjusted for whole-brain volume. Error bars represent standard error. *p < 0.0083 (Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons), within-group t tests. Effect of trauma within gene groups was not tested due to the limited number of Met allele carriers

Significant within-group findings were further confirmed by trauma-by-BDNF interactions in the full sample (controlling for IQ) for right subcallosal, F(1,41) = 7.49, p = 0.009, and right hippocampal GMV, F(1,41) = 4.13, p = 0.049. No main effects of BDNF or trauma on GMV were observed, ps > 0.09. Additional supplementary analyses excluding outliers and missing values yielded consistent results: GMV of right hippocampus, t(30) = 2.59, p = 0.015, and right subcallosal area, t(32) = 3.08, p = 0.004, was higher in Met alleles than in Val/Met participants in the comparison group, and BDNF effects were not significant in the trauma group in these areas, p = 0.87 and p = 0.52, respectively.

To account for racial heterogeneity in the sample, subsequent analyses additionally co-varying for race were conducted, yielding no changes to the results. Specifically, main effects of BDNF genotype were significant for right subcallosal, F(1, 31) = 8.5, p = 0.007, and right hippocampal GMV, F(1, 31) = 8.64, p = 0.006, in comparison youth.

Results in the case–comparison matched subsample (equal number of Val/Val and Met participants) replicated the trauma-by-BDNF interaction on GMV of the right subcallosal area, F(1,14) = 13.36, p = 0.003. However, the trauma-by-BDNF interaction was not replicated for right hippocampal GMV, p = 0.32.

Relation of GMV to age, pubertal stage, sex, and internalizing symptoms

No sex differences in GMV were noted across ROIs, ps > 0.18. In addition, no trauma-by-sex interactions were observed for right hippocampal, F(1,51) = 1.73, p = 0.195, or right subcallosal GMV, F(1,51) = 2.12, p = 0.15. GMV of right hippocampus and right subcallosal area was not related to age or pubertal (Tanner) stage, ps > 0.12. Although anxiety and depressive symptoms did not differ between BDNF and trauma groups, we tested for correlations between ROI GMV and internalizing symptoms. Within the comparison group, right hippocampal GMV was negatively correlated with anxiety symptomology (SCR-C), r(34) = −0.39, p = 0.021. This relationship was not evident in the trauma group, r(21) = 0.33, p = 0.14.

Discussion

Emerging research indicates that impairments in neuroplasticity and cellular resilience induced through stress underlie risk for affective disorders (see [21]). As many of these disorders have their roots in childhood and adolescence [52], examining how prominent biological (i.e., altered BDNF function) and environmental (i.e., trauma) risk factors shape the brain in formative years may critically inform pathways responsible for lifelong emotional health. Here, we provide preliminary evidence that childhood trauma and BDNF Val66Met genotype interact to predict structural variation in limbic brain regions, known to regulate mood, in a sample of youth at high risk for emotional psychopathology. Altered development of limbic brain circuitry may lead to emotion dysregulation and pathology. Our results suggest that individual variation in BDNF neurobiology plays a central role in modifying vulnerability (or resilience) to traumatic stress.

We demonstrate a trauma-by-BDNF interaction in the subcallosal region, such that BDNF effects on GMV were observed in comparison but not trauma-exposed youth (see Fig. 2). Control participants with a Met allele had larger subcallosal GMV. In addition, trauma-exposed Met allele carriers appeared to have lower GMV relative to Met carriers without histories of trauma, but this difference was not significant possibly due to the modest number of Met alleles in the sample. It is nonetheless striking that these observations are consistent with those previously reported in a large (n = 568) sample of healthy adults [29]. Gerritsen and colleagues observed lower GMV in the subcallosal region in adults exposed to childhood trauma that also carry the Met allele. Volume reduction in this area is a consistent finding in mood disorders (for review, see [20]), and the subcallosal area is a target for deep brain stimulation in the treatment of depression [46]. There is also data to suggest that altered structural integrity of the subcallosal area underlies stress susceptibility [51, 54]. Research in experimental animals implicates the subcallosal region in the regulation of autonomic and neuroendocrine stress responses [61]. Taken together, our results provided preliminary support that subcallosal gray matter alterations could be an early indicator of risk that results from interaction of childhood trauma with genetic susceptibility.

We also found preliminary evidence for differential effects of BDNF genotype on hippocampal GMV in youth that did or did not experience trauma. Met allele children without histories of trauma had increased hippocampal GMV relative to Val/Val children (see Fig. 3). This effect was not observed in the trauma group. This suggests that BDNF-related hippocampal differences may be evident only in the absence of early traumatic stress. It is likely that certain types of environmental exposures, such as early trauma, can mask or override aspects of genetic disposition, for example through epigenetic mechanisms. As such, experience has the potential to diminish differences between gene groups. Having observed higher hippocampal GMV in children without trauma may reflect differences in plasticity [12], in neurogenesis [55], and/or in learning and memory [18]—all of which have been linked to BDNF profile and hippocampal integrity. It is unknown whether these differences similarly manifest in children that endure difficult early life experiences, but it is possible the gene-related distinctions are reduced.

In contrast to research in previously institutionalized children that was also preliminary [8], we did not observe trauma-by-BDNF effects in the amygdala. In that study, Met allele carriers were more likely to show increases in amygdala GMV following early life stress than individuals homozygous for the Val allele. Another study found increased GMV of the amygdala in adolescents exposed to maternal depression during infancy [44]. Taken together, amygdala volume changes detected during childhood may relate to trauma experienced during very early postnatal life. This is in line with nonhuman primate research showing that the most rapid rate of amygdala development occurs during infancy [50]. Moreover, given the variable role of BDNF at different developmental ages (see [8]), trauma-by-BDNF effects may differ depending on the age that trauma is experienced. Indeed, BDNF appears to exert either a permissive or obstructive role on activity-dependent synaptic changes, depending on the brain region and developmental stage [56]. This is consistent with the view that stress during different developmental windows may lead to disparate neurobiological and psychiatric consequences [63]. Another possibility for our null finding is that amygdala volume changes may relate to type of trauma (e.g., disrupted early nurturing). If this is the case, variability in types of adversity experienced in our sample (e.g., witnessing domestic violence, physical or sexual abuse) would diminish our ability to detect significant effects at the group level.

It should be noted that GMV changes are difficult to interpret. GMV differences are often interpreted as changes in the number or size of glial cells, neurons, dendrites, or synapses (cf. [20]); however, changes in intracortical myelination may also contribute to GMV alterations (cf. [62]). Moreover, gross volumetric differences might not be as sensitive as effects on subregions. For instance, a recent study in adults reporting histories of childhood trauma found trauma-by-BDNF effects on specific subregions of the hippocampus (i.e., CA2/3; [25]). Continued research will address regional specificity and cellular changes that underlie structural MRI GMV differences, and will contribute understanding to how BDNF modulates limbic brain structures over the course of development.

Study limitations warrant mention. Due to the limited sample size and the rarity of the Met allele, current results are presented as preliminary. These preliminary findings do, however, highlight neurological differences in an understudied population of urban-dwelling, minority youth with a high stress burden. Moreover, our results suggest interacting effects of trauma and BDNF on limbic GMV in ways that differ from an earlier preliminary report in youth [8]. The fact that our findings mirror those reported in a study of adults reporting early stress [29] affords further confidence in the observed pattern. Given the rarity of the Met allele, future studies may also consider performing genotyping prior to enrolling participants in the neuroimaging protocol. Next, findings in this report are based on a racially heterogeneous sample. We controlled for possible effects of race (which shows high correspondence with genotyped ancestry markers; [19]) in follow-up analyses; doing so allowed us to increase overall power by including all participants in analyses. While we were underpowered to confirm observed effects within race subgroups, our analyses do support the conclusion that results reported here are not likely attributable to population structure artifact. Similarly, we were underpowered to test for sex-by-BDNF effects on GMV in this sample and we urge future studies to address this important question. In addition, participants spanned a broad age range (7–15 years) and thus impacts of age and pubertal development should be considered. Although this preliminary study was not sufficiently powered to assess the effects of age on study outcomes, we were sensitive to these concerns. We found that age and pubertal stage did not differ between BDNF groups, or between trauma and comparison participants. Additionally, we did not find age- or puberty-related associations with GMV of ROIs showing trauma-by-BDNF effects (i.e., right hippocampus, right subcallosal area). Finally, in an effort to extend prior work in adults [29] and to limit the number of comparisons, we investigated only a subset of ROIs. Future work should evaluate effects of trauma and BDNF on other brain regions.

The present study provides preliminary evidence that, among high-risk urban youth, childhood trauma and BDNF genotype interact to predict variation in limbic brain regions during formative, developmental years. It is notable that BDNF effects were observed only in the absence of traumatic stress, supporting the conclusion that certain environmental contexts may be necessary to mask or unmask gene–brain associations. These data suggest that genetic variability may contribute to variable neurodevelopmental pathways leading to poor outcomes following early life trauma [14]. On the basis of these early results, however, it is unclear whether Met allele carriers are more prone to the detrimental effects of trauma on hippocampal and subcallosal gray matter integrity, or instead, trauma leads to decreased GMV, irrespective of genotype, and normalization is impaired in Met allele carriers (resulting in no observed effects of BDNF within the trauma group). In addition, trauma-exposed youth did not report higher levels of anxiety or depressive symptomology, suggesting that neurological effects observed in the dynamically developing brain may represent risk or adaptation to adverse early environments. We did, however, observe a negative correlation between hippocampal GMV and anxiety symptomology in youth without histories of trauma. This is consistent with the notion that early experience modulates gene–brain or gene–symptom effects. Future research should examine relationships among trauma, limbic brain circuitry, and psychiatric outcomes over the course of development, considerate of developmental changes in BDNF function.

Conclusions

In summary, this preliminary study demonstrates an interactive effect of BDNF genotype and childhood trauma on limbic GMV in youth. Our results support the notion that the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism functions as a stress vulnerability (and/or resiliency) factor in early life. It is critical that these effects were observed in children, whose brains are undergoing substantial maturational changes [17]. Research shows that psychopathology frequently emerges during childhood and adolescence, and once it manifests, it often becomes chronic [13]. It has been demonstrated that about 60 % of youth will experience a traumatic event before adulthood [48] and nearly a third of trauma-exposed youth will go on to develop an affective disorder [31]. These findings are a first step towards understanding the mechanisms through which early adversity forms a prelude to psychopathology, so that predictive biomarkers of risk may be identified. Future research in this area may carry implications for preventive interventions, including those that operate through BDNF pathways to re-open or extend developmental windows of plasticity [10].

References

Aguilera M, Arias B, Wichers M, Barrantes-Vidal N, Moya J, Villa H, van Os J, Ibanez MI, Ruiperez MA, Ortet G, Fananas L (2009) Early adversity and 5-HTT/BDNF genes: new evidence of gene–environment interactions on depressive symptoms in a general population. Psychol Med 39(9):1425–1432

Alim TN, Charney DS, Mellman TA (2006) An overview of posttraumatic stress disorder in African Americans. J Clin Psychol 62(7):801–813

Baker LM, Williams LM, Korgaonkar MS, Cohen RA, Heaps JM, Paul RH (2013) Impact of early vs. late childhood early life stress on brain morphometrics. Brain Imaging Behav 7(2):196–203

Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, Neer SM (1997) The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(4):545–553

Briere J, Runtz M (1990) Differential adult symptomatology associated with three types of child abuse histories. Child Abuse Negl 14(3):357–364

Calabrese F, Molteni R, Racagni G, Riva MA (2009) Neuronal plasticity: a link between stress and mood disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34(1(0)): S208–S216

Carballedo A, Morris D, Zill P, Fahey C, Reinhold E, Meisenzahl E, Bondy B, Gill M, Moller HJ, Frodl T (2013) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism and early life adversity affect hippocampal volume. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 162B(2):183–190

Casey BJ, Glatt CE, Tottenham N, Soliman F, Bath K, Amso D, Altemus M, Pattwell S, Jones R, Levita L, McEwen B, Magarinos AM, Gunnar M, Thomas KM, Mezey J, Clark AG, Hempstead BL, Lee FS (2009) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a model system for examining gene by environment interactions across development. Neuroscience 164(1):108–120

Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE (2010) Genetic sensitivity to the environment: the case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. Am J Psychiatry 167(5):509–527

Castren E, Rantamaki T (2010) The role of BDNF and its receptors in depression and antidepressant drug action: reactivation of developmental plasticity. Dev Neurobiol 70(5):289–297

Charney DS, Manji HK (2004) Life stress, genes, and depression: multiple pathways lead to increased risk and new opportunities for intervention. Sci STKE 2004(225): re5

Cheeran B, Talelli P, Mori F, Koch G, Suppa A, Edwards M, Houlden H, Bhatia K, Greenwood R, Rothwell JC (2008) A common polymorphism in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene (BDNF) modulates human cortical plasticity and the response to rTMS. J Physiol 586(Pt 23):5717–5725

Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ (2006) Developmental psychopathology, theory and method. Wiley, New York

Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA (1996) Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 8(04):597–600

Dannlowski U, Stuhrmann A, Beutelmann V, Zwanzger P, Lenzen T, Grotegerd D, Domschke K, Hohoff C, Ohrmann P, Bauer J, Lindner C, Postert C, Konrad C, Arolt V, Heindel W, Suslow T, Kugel H (2012) Limbic scars: long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment revealed by functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging. Biol Psychiatry 71(4):286–293

De Bellis MD (2001) Developmental traumatology: the psychobiological development of maltreated children and its implications for research, treatment, and policy. Dev Psychopathol 13(3):539–564

Dichter GS, Felder JN, Petty C, Bizzell J, Ernst M, Smoski MJ (2009) The effects of psychotherapy on neural responses to rewards in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 66(9):886–897

Dincheva I, Glatt CE, Lee FS (2012) Impact of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on cognition: implications for behavioral genetics. Neuroscientist 18(5):439–451

Divers J, Redden DT, Rice KM, Vaughan LK, Padilla MA, Allison DB, Bluemke DA, Young HJ, Arnett DK (2011) Comparing self-reported ethnicity to genetic background measures in the context of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). BMC Genet 12:28

Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML (2008) Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Struct Funct 213(1–2):93–118

Duman RS, Monteggia LM (2006) A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 59(12):1116–1127

Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Bertolino A, Zaitsev E, Gold B, Goldman D, Dean M, Lu B, Weinberger DR (2003) The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell 112(2):257–269

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39(2):175–191

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 14(4):245–258

Frodl T, Skokauskas N, Frey EM, Morris D, Gill M, Carballedo A (2014) BDNF Val66Met genotype interacts with childhood adversity and influences the formation of hippocampal subfields. Hum Brain Mapp 35(12):5776–5783

Furman DJ, Chen MC, Gotlib IH (2011) Variant in oxytocin receptor gene is associated with amygdala volume. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36(6):891–897

Gallinat J, Schubert F, Bruhl R, Hellweg R, Klar AA, Kehrer C, Wirth C, Sander T, Lang UE (2010) Met carriers of BDNF Val66Met genotype show increased N-acetylaspartate concentration in the anterior cingulate cortex. Neuroimage 49(1):767–771

Gatt JM, Nemeroff CB, Dobson-Stone C, Paul RH, Bryant RA, Schofield PR, Gordon E, Kemp AH, Williams LM (2009) Interactions between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and early life stress predict brain and arousal pathways to syndromal depression and anxiety. Mol Psychiatry 14(7):681–695

Gerritsen L, Tendolkar I, Franke B, Vasquez AA, Kooijman S, Buitelaar J, Fernandez G, Rijpkema M (2012) BDNF Val66Met genotype modulates the effect of childhood adversity on subgenual anterior cingulate cortex volume in healthy subjects. Mol Psychiatry 17(6):597–603

Giedd JN, Vaituzis AC, Hamburger SD, Lange N, Rajapakse JC, Kaysen D, Vauss YC, Rapoport JL (1996) Quantitative MRI of the temporal lobe, amygdala, and hippocampus in normal human development: ages 4–18 years. J Comp Neurol 366(2):223–230

Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S (2009) Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 373(9657):68–81

Goldmann E, Aiello A, Uddin M, Delva J, Koenen K, Gant LM, Galea S (2011) Pervasive exposure to violence and posttraumatic stress disorder in a predominantly African American Urban Community: the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study. J Trauma Stress 24(6):747–751

Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC (2010) Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(2):113–123

Hashimoto K, Shimizu E, Iyo M (2004) Critical role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in mood disorders. Brain Res Rev 45(2):104–114

Hasler G (2010) Pathophysiology of depression: do we have any solid evidence of interest to clinicians? World Psychiatry 9(3):155–161

Joffe RT, Gatt JM, Kemp AH, Grieve S, Dobson-Stone C, Kuan SA, Schofield PR, Gordon E, Williams LM (2009) Brain derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism, the five factor model of personality and hippocampal volume: implications for depressive illness. Hum Brain Mapp 30(4):1246–1256

Joshi AA, Shattuck DW, Leahy RM (2012) A fast and accurate method for automated cortical surface registration and labeling. In: Proceedings of the WBIR. LNCS. Springer, Berlin, pp 180–189

Joshi AA, Shattuck DW, Thompson PM, Leahy RM (2007) Surface-constrained volumetric brain registration using harmonic mappings. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 26(12):1657–1669

Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL (2004) Kaufman brief intelligence test: KBIT 2; Manual. Pearson, London

Kaufman J, Yang BZ, Douglas-Palumberi H, Grasso D, Lipschitz D, Houshyar S, Krystal JH, Gelernter J (2006) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-5-HTTLPR gene interactions and environmental modifiers of depression in children. Biol Psychiatry 59(8):673–680

Kitayama N, Vaccarino V, Kutner M, Weiss P, Bremner JD (2005) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 88(1):79–86

Kovacs M (1992) Children’s depression inventory. Multi-Health Systems Incorporated, Toronto

Lim L, Radua J, Rubia K (2014) Gray matter abnormalities in childhood maltreatment: a voxel-wise meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 171(8):854–863

Lupien SJ, Parent S, Evans AC, Tremblay RE, Zelazo PD, Corbo V, Pruessner JC, Seguin JR (2011) Larger amygdala but no change in hippocampal volume in 10-year-old children exposed to maternal depressive symptomatology since birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(34):14324–14329

Marshall WA, Tanner JM (1968) Growth and physiological development during adolescence. Annu Rev Med 19:283–300

Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, Schwalb JM, Kennedy SH (2005) Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 45(5):651–660

McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ (2011) Stress- and allostasis-induced brain plasticity. Annu Rev Med 62:431–445

McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC (2013) Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52(8):815–830 e814

McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Lambert HK (2014) Childhood adversity and neural development: deprivation and threat as distinct dimensions of early experience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 47:578–591

Payne C, Machado CJ, Bliwise NG, Bachevalier J (2010) Maturation of the hippocampal formation and amygdala in Macaca mulatta: a volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. Hippocampus 20(8):922–935

Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R (2003) Neurobiology of emotion perception I: the neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biol Psychiatry 54(5):504–514

Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y (1998) The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55(1):56–64

Poo MM (2001) Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat Rev Neurosci 2(1):24–32

Radley JJ, Williams B, Sawchenko PE (2008) Noradrenergic innervation of the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex modulates hypothalamo-pituitary–adrenal responses to acute emotional stress. J Neurosci 28(22):5806–5816

Rossi C, Angelucci A, Costantin L, Braschi C, Mazzantini M, Babbini F, Fabbri ME, Tessarollo L, Maffei L, Berardi N, Caleo M (2006) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is required for the enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis following environmental enrichment. Eur J Neurosci 24(7):1850–1856

Schinder AF, Poo M (2000) The neurotrophin hypothesis for synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci 23(12):639–645

Shattuck DW, Leahy RM (2001) Automated graph-based analysis and correction of cortical volume topology. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 20(11):1167–1177

Shattuck DW, Leahy RM (2002) BrainSuite: an automated cortical surface identification tool. Med Image Anal 6(2):129–142

Shattuck DW, Sandor-Leahy SR, Schaper KA, Rottenberg DA, Leahy RM (2001) Magnetic resonance image tissue classification using a partial volume model. Neuroimage 13(5):856–876

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL (1979) Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 86(2):420–428

Sullivan RM, Gratton A (1999) Lateralized effects of medial prefrontal cortex lesions on neuroendocrine and autonomic stress responses in rats. J Neurosci 19(7):2834–2840

Toga AW, Thompson PM, Sowell ER (2006) Mapping brain maturation. Trends Neurosci 29(3):148–159

Tottenham N, Sheridan MA (2009) A review of adversity, the amygdala and the hippocampus: a consideration of developmental timing. Front Hum Neurosci 3:68

Uematsu A, Matsui M, Tanaka C, Takahashi T, Noguchi K, Suzuki M, Nishijo H (2012) Developmental trajectories of amygdala and hippocampus from infancy to early adulthood in healthy individuals. PLoS One 7(10):e46970

van Harmelen AL, van Tol MJ, van der Wee NJ, Veltman DJ, Aleman A, Spinhoven P, van Buchem MA, Zitman FG, Penninx BW, Elzinga BM (2010) Reduced medial prefrontal cortex volume in adults reporting childhood emotional maltreatment. Biol Psychiatry 68(9):832–838

Webster MJ, Weickert CS, Herman MM, Kleinman JE (2002) BDNF mRNA expression during postnatal development, maturation and aging of the human prefrontal cortex. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 139(2):139–150

Wichers M, Kenis G, Jacobs N, Mengelers R, Derom C, Vlietinck R, van Os J (2008) The BDNF Val(66)Met × 5-HTTLPR × child adversity interaction and depressive symptoms: an attempt at replication. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 147B(1):120–123

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute and the Department of Pediatrics, Wayne State University (WSU) School of Medicine, a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award (MET), NIH National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences awards P30 ES020957 and R21 ES026022 (MET), and the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders And Stroke award R01 NS074980 (DWS and AAJ). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The WSU Genomics Core is supported, in part, by NIH National Cancer Institute award P30 CA022453. The authors thank Zahid Latif and Yashwanth Katkuri of WSU for their assistance in neuroimaging data acquisition, Kayla Martin, Gregory H. Baldwin, Rita Elias, Melissa Youmans, Mallory Gardner, Amy Katherine Swartz, Timothy Lozon, Berta Rihan, and Ali Daher of WSU for assistance in participant recruitment and data collection, Julianne Facca, Matthew Hess, and Susan Land of the WSU Applied Genomics Technology Center for assistance with genetic analyses, and the children and families who generously shared their time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marusak, H.A., Kuruvadi, N., Vila, A.M. et al. Interactive effects of BDNF Val66Met genotype and trauma on limbic brain anatomy in childhood. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25, 509–518 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0759-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0759-4