Abstract

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) has onset in adolescence, but is typically first diagnosed in young adulthood. This paper provides a narrative review of the current evidence on diagnosis, comorbidity, phenomenology and treatment of BPD in adolescence. Instruments available for diagnosis are reviewed and their strengths and limitations discussed. Having confirmed the robustness of the diagnosis and the potential for its reliable clinical assessment, we then explore current understandings of the mechanisms of the disorder and focus on neurobiological underpinnings and research on psychological mechanisms. Findings are accumulating to suggest that adolescent BPD has an underpinning biology that is similar in some ways to adult BPD but differs in some critical features. Evidence for interventions focuses on psychological therapies. Several encouraging research studies suggest that early effective treatment is possible. Treatment development has just begun, and while adolescent-specific interventions are still in the process of evolution, most existing therapies represent adaptations of adult models to this developmental phase. There is also a significant opportunity for prevention, albeit there are few data to date to support such initiatives. This review emphasizes that there can be no justification for failing to make an early diagnosis of this enduring and pervasive problem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper was commissioned by the European Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (ESCAP) as part of one of the themes for the 2015 ESCAP Congress. A working group representing several European countries and drawing on international collaborations met to discuss the clinical issues raised by early diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and drafted this position paper.

Past reluctance to diagnose BPD in adolescence has included concerns about stigma, the difficulty of distinguishing ‘normal’ adolescent turmoil from BPD and the incompleteness of personality development in this age group [1, 2]. This expert review of the extant literature was undertaken in order to establish whether sufficient data exist to justify BPD as a valid and reliable diagnosis in adolescence, with a clearly definable presentation, course and outcome that separates it from other disorders. Furthermore, we are keen to establish whether enough is known about disease mechanisms specific to BPD to justify linking adolescent presentation to the adult disorder, and whether adolescent BPD could be seen as an early stage of adult BPD or a separate diagnosis. Finally, the relevance of any diagnosis rests on the availability of appropriate interventions. Our review also examined the extant literature on evidence-based biological and psychosocial treatments. We also discuss potentially promising treatments that are currently in development.

The overarching aim of the review is to provide a platform for a timely and much-needed discussion about current practice in relation to the diagnosis and treatment of BPD in adolescence. BPD is a distressing and sometimes lifelong condition [3] accompanied by substantial personal, social and economic burdens [4–6]. The success of the early and rapid treatment of psychoses in adolescence should encourage us to take a similar proactive and courageous approach to the treatment of personality disorder. This cannot happen without a substantial research platform upon which early interventions could be based.

Phenomenology of borderline personality disorders in adolescence

The diagnosis of BPD in adolescents has been a topic of debate in recent years, with controversial reports concerning its validity and its stability over time [7, 8]. Despite long-standing agreement that personality disorders have their roots in childhood and adolescence, clinicians have been overall reluctant to diagnose personality disorders during this age period, as adolescents are undergoing fast-changing developmental processes [9]; from this point of view, even ‘adolescence’ should not be considered as a single developmental period [10]. Controversy over the legitimacy of the diagnosis may be most justifiable when it concerns those children who have just entered adolescence (11–13 year olds), about whom extant studies say surprisingly little [11]. However, although to date there are no official developmentally focused criteria for BPD, current psychiatric classification systems imply that personality disorder categories (including BPD) can be applied to children and young people in cases where the maladaptive personality traits appear to be pervasive and persistent (at least 1 year), and are considered unlikely to be limited to a particular developmental stage [12, p. 647, 13, p. 123]. Moreover, recent reviews have concluded that the reliability and validity of the diagnosis of BPD in at least middle-to-late adolescence is comparable to that in adulthood [8, 14–16]. In line with this, several national treatment guidelines [17–21] acknowledge that diagnosing BPD is now justified and practical in adolescence.

Using DSM-IV criteria, the prevalence of BPD in adolescents is similar to or higher than that found in adults: approximately 3 % of community dwellers [22], 11 % of outpatients [23, 24], and up to 50 % of inpatients [25]. The disorder identifies a group of adolescents with high co-occurring mental disorders and poor outcome [15]. It predicts current psychopathology and psychosocial dysfunction [26], as well as negative outcome in longitudinal studies [27, 28].

In adults, the essential feature of BPD is a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, emotion regulation and marked impulsivity that is present in a variety of contexts. On a psychological level, high rejection sensitivity, difficulties with trust and cooperation, shame proneness, negative self- and body perception, and intermittent hostility are at the core of both adolescent and adult clinical presentations; however, the importance of these specific constructs will need to be confirmed in future systematic studies of BPD in adolescents.

While there are some differences between adolescents and adults in diagnostic-related phenomena associated with BPD, a review concluded that these differences can be explained by the principle of heterotypic continuity in development (suggesting a developmental process of continuing and consistent impairment with changing manifestations) [29]. Reported differences between adults and adolescents concern the dominance of specific diagnostic criteria at certain stages of development [30]. Compared with adults, adolescents who are identified as having BPD are more likely to present with the more ‘acute’ (executive) symptoms of BPD, such as recurrent self-harm and suicidal behaviour, other impulsive and self-damaging behaviours and inappropriate anger. In contrast, enduring characteristic symptoms, such as unstable relationships and identity disturbances, are more often diagnosed among adults with BPD [31]. However, fear of abandonment was found to be the most specific inclusion criterion for adolescents [32], with patients having an 85 % chance of meeting full diagnostic criteria when they endorsed this symptom. Similarly, Westen and colleagues [33] assessed the potential manifestations of identity disturbance in adolescence and concluded that the features most distinctively associated with a diagnosis of BPD were feelings of emptiness, fluctuations in self-perception and dependency on specific relationships to maintain a sense of identity. Nonetheless, due to the over-representation of acute symptoms in adolescent BPD, it is critical to carefully distinguish acute mental states (which might occur during a mental state disorder or a developmental crisis) from traits that indicate a more general pattern of maladaptive and dysfunctional behaviours. Future work will have to demonstrate how early specific symptoms differ from early manifestations of full BPD in order for clinicians to have clear indications of when specialized intervention may be appropriate, and at what dosage.

The current literature suggests that the presentation of individual symptoms is likely to vary over time, but that an accurate diagnosis can be made by considering core dysfunctional areas of BPD such as affective dysregulation, interpersonal disturbances and impulsivity or behavioural dysregulation, which are intrinsically linked to each other [34, 35] (see also the section on psychological mechanisms). Several studies have shown that the categorical stability of BPD in adolescents is relatively low [27, 36, 37]. It appears that a dimensional approach might lead to greater stability compared with the use of categorical diagnoses. The dimensional approach uses selected symptoms or dimensions, such as impulsivity, negative affectivity and interpersonal aggression, which are known to be significant predictors of a BPD diagnosis in both adolescents and adults [38]. Conceptualizing BPD from a dimensional, rather than a categorical, perspective could be particularly pertinent in adolescents, as a dimensional approach may better account for the developmental variability and heterogeneity observed during this age period [8, 23, 24].

Of particular note are the newly proposed diagnostic entities of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) disorder and suicidal behaviour disorder, which have been included in Section III of DSM-5 [12]. NSSI is a common feature in early adolescence and may be associated with a range of clinical syndromes. However, repetitive NSSI might differ from occasional NSSI and be associated with BPD at this age [39]. Moreover, the likelihood of meeting the diagnosis of BPD is greater in adolescents reporting both NSSI and suicide attempts than in individuals reporting either NSSI or suicide attempts [40]. While there is no doubt that all forms of self-harm can be undertaken independently of BPD, descriptive diagnoses of pure behaviours or symptoms such as NSSI and suicide attempts may detract from important underlying psychopathological factors such as dimensional features of personality pathology and thus prevent specific interventions.

Diagnosing BPD in adolescence

Despite strong evidence for the early identification of individuals with BPD, stigma is a key lingering barrier to early diagnosis in day-to-day clinical practice [41]. BPD is highly stigmatized among professionals [42] and is sometimes associated with patient ‘self-stigma’ [1, 43]. While concerns about stigma are genuine and the response is well intentioned, this practice runs the risk of perpetuating negative stereotypes, reducing the prospect of applying specific beneficial interventions and education for the problems associated with BPD and increasing the likelihood of inappropriate diagnoses and interventions and iatrogenic harm (such as polypharmacy) [41]. As for most other disorders, there is likely to be a negative correlation between the duration of illness and the prognosis of BPD, and early detection of and intervention for adolescent BPD should therefore become a crucial goal for European health care systems. Increasing knowledge about BPD in adolescence is likely to make its early detection feasible and perhaps even conventional. This might result in timely and specific evidence-based interventions that target comorbid psychiatric disorders, reduce impairment of psychosocial functioning and consequently improve the prognosis for adolescents with BPD [15]. Clinical experience suggests that inappropriate or insufficient psychiatric treatment often reinforces dysfunctional behaviour. Early diagnosis and appropriate evidence-based interventions are required to reduce these serious, long-lasting and stigmatizing iatrogenic problems. Most individuals with early BPD symptoms will be seen by a general practitioner, a pediatrician or another health care worker. Early detection thus relies upon these practitioners’ knowledge of the clinical indicators of BPD and the existence of appropriate networks to refer young people to mental health professionals [15]. Reliable diagnosis of BPD is essential and the use of well-established interview tools to support clinical assessment is highly recommended [44]. The official tools of the DSM-IV (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders; SCID-II [45] and ICD-10 International Personality Disorder Examination; IPDE [46]) have been widely used in clinical and research settings for adults and have also been successfully adopted for the adolescent population [24, 30, 47–49]. A recent development was the validation of the Childhood Interview for DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder (CI-BPD) [50], which is the first interview-based measure of adolescent BPD and shows good reliability and validity [51]. In addition, interview-based assessments of symptoms from multiple sources including adolescents and parents are recommended, as each source provides unique information about symptoms [52, 53]. Despite the fact that the measures listed above allow reliable and valid diagnosis of adolescent BPD, current classification systems and assessment tools require further work to establish unequivocal developmentally adapted criteria for BPD that account for the normative changes across the normal and abnormal spectrum of personality during adolescence [54].

Self-report scales have been widely used in population-based studies of BPD and as screening measures in clinical settings. Widely used examples from the adult population, which have also been usefully employed in adolescent samples, are the BPD items of the SCID-II Personality Questionnaire (SCID-II-PQ) [24, 45], the Borderline Personality Questionnaire (BPQ) [24, 48, 55], the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD) [56], and the International Personality Disorder Examination Screening Questionnaire (IPDE-SQ) [57], along with measures of symptom severity such as the Borderline Symptom List (BSL) [58, 59]. Specifically for children and adolescents, there is the Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children (BPFS-C) [60], including a newly developed parent report version of the measure (BPFS-P) [61]. All scales mentioned have been validated, and showed good-to-satisfactory psychometric properties. The SCID-II-PQ, the MSI-BPD, the IPDE-SQ and the BPQ have all been investigated for screening purposes among youth, with the best results reported for the BPQ [24]. While these measures may all be used for screening purposes among adolescents, it is important to note that BPD should never be diagnosed solely on the basis of self-report questionnaires.

Comorbidity of BPD in adolescence

BPD in adolescents demarcates a group with high psychiatric comorbidity and low psychosocial functioning [30, 62–64]. Compared to psychiatric inpatients without BPD, borderline adolescents are significantly more likely to meet criteria for psychiatric disorders in the area of externalizing problems (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional and conduct disorders), substance abuse/dependence problems, and internalizing disorders including mood and anxiety disorders (obsessive–compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, separation anxiety disorder and social phobia) [30, 47, 64]. Moreover, a significantly higher percentage of BPD patients (up to 60 %) met criteria for complex comorbidity, which can be defined as a confluence of internalizing and externalizing disorders (e.g. having any mood or anxiety disorder plus a disorder of impulsivity) [47, 65]. According to Ha and colleagues [64], such complex comorbidity increases the likelihood of adolescents receiving a BPD diagnosis. This implies that clinicians should be aware that among help-seeking adolescents, complex comorbidity may suggest the presence of a BPD diagnosis. Moreover, these findings have recently led to the suggestion of using this characteristic mixture of high levels of both internalizing and externalizing problems as a warning sign that may indicate a possible diagnosis of BPD in adolescents, thus warranting a specific diagnostic assessment [15]. This is supported by longitudinal studies that have shown that disruptive behaviour disorders along with depressive symptoms in childhood are predictive of BPD diagnoses in adolescence [66]; consequently, this represents one possible developmental pathway to BPD [67]. While results are consistent with the existing adult literature, these data provide additional evidence toward the overall construct validity of BPD in adolescents.

Mechanisms of BPD in adolescence

The view that core impairments in BPD are intrinsically related is consistent with three recent large twin studies that suggest a common pathway model with one highly heritable general BPD factor [68–70]. This view is also consistent with factor analytic studies in adolescents suggesting that BPD in adolescence is best represented by a single hierarchical superordinate factor [51, 71].

We have only limited data available on the mechanisms specific to BPD in adolescence. Here, we discuss growing insights into the psychological and biological mechanisms of the key features of BPD in adolescence, drawing from both the adult and the child/adolescent literature. We assume that what we know in relation to adult-diagnosed cases is likely to be relevant to understanding the developmental pathways leading to the condition in adolescents, but we also focus on potential differences between the presentation of BPD in adults and in adolescents that are emerging from this body of findings. Unfortunately, extant research does not yet support a comprehensive data-based developmental theory of BPD.

Genetics

Twin studies suggest that BPD features in adulthood have an estimated heritability of around 40–50 % [72–75]. However, as yet, no specific genes have been associated with BPD [35].

Two studies found that children and adolescents (aged 9–15 years) who carried the s-allele of 5-HTTLPR (the serotonin transporter gene promoter region) had the highest levels of BPD features [76]. This is congruent with the view that BPD is associated with high stress sensitivity, which may drive the key features of the disorder. In a nationally representative birth cohort of over 1100 families with twins, Belsky et al. [77] found a highly significant interaction between maltreatment and BPD features assessed at age 12, but only in children with a family history of psychopathology as an index of genetic vulnerability. Currently, most other genetic studies on BPD are based on small samples and require replication.

Neuroimaging

Structural imaging and spectroscopy

Among the most robust findings of structural imaging in adult BPD patients are reduced volumes of the amygdala, hippocampus, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC); these are brain areas that play a key role in emotion regulation and the processing of social information. A recent meta-analysis of 11 studies comprising 205 BPD patients and 222 healthy controls showed an average decrease of 11 % in the size of the hippocampus and of 13 % in the size of the amygdala in patients relative to controls [78].

Reduced volumes of the left ACC and right OFC have also been found in adolescent BPD patients, and were found to correlate with impulsivity and NSSI [79–81]; however, negative results for the ACC [79] and OFC [82] have also been reported. Furthermore, one study reported no differences in the volume of the amygdala or hippocampus in adolescent BPD [80], while, in contrast, Richter and colleagues [83] reported reduced volumes in these structures, congruent with findings in the adult literature. A recent study also reported an association between atypical hippocampal asymmetry and BPD features in interaction with temperamental features [84].

Diffusion tensor imaging studies have shown decreased fractional anisotropy in the fornix of adolescents with BPD [85]. New and colleagues [86] reported decreased fractional anisotropy in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus and other areas in adolescents, but not in adults, with BPD, which may point to a transient impairment in connectivity in the development of BPD (see also ‘Psychological mechanisms’, below).

Inconsistent findings in adolescents with BPD may be explained by heterogeneous samples, and by the fact that structural brain changes typically associated with BPD in adulthood have not yet fully materialized, which would emphasize the importance of early intervention. In addition, it is not yet clear whether findings concerning brain abnormalities are specific for adolescent BPD and/or reflect trauma or general vulnerability for psychopathology [87].

Functional imaging

Functional neuroimaging studies in adult BPD patients suggest that impairments in connectivity between the medial frontal cortex and OFC, amygdala, hippocampus, posterior cingulate and insular cortex (for a review, see [88]) may underlie the typical features of BPD. To date, one fMRI study conducted in adolescents with repetitive NSSI has been able to replicate findings of amygdala hyperresponsiveness [89].

Neurobiological studies

BPD in adults has been associated with dysfunctions in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (for reviews, see [90, 91]). The most robust findings in experimental stress paradigms can be interpreted as attenuated peripheral cortisol release [92]. These findings have been confirmed in self-harming adolescents [93]. HPA data in adolescents are rather preliminary and even controversial (e.g. [94]), but these findings might be interpreted within a bimodal temporal model, wherein chronic stress-induced hypercortisolism leads to long-term HPA depletion. Early chronic stress has been shown to initially lead to a pattern of HPA axis hyperresponsiveness; however, in later life this may switch to either hyporesponsiveness of the HPA axis or low central and/or peripheral cortisol release in response to stress [95].

Environmental factors

There is now good evidence from longitudinal studies suggesting that a mix of adverse childhood experiences (emotional neglect and abuse in particular), a broader problematic family environment and low socioeconomic status are associated with the key features of BPD (for reviews, see [34, 96]). The Children in the Community Study [97], for instance, found that documented childhood maltreatment was prospectively associated with a highly increased risk for BPD in young adulthood even when controlling for symptoms of other personality disorders, age, parental education, and parental psychiatric disorders (adjusted odds ratio = 7.7). In this study, low socioeconomic status and early maternal separation also emerged as predictors of BPD symptoms assessed repeatedly from early adolescence to middle adulthood, and were largely independent from other predictors such as maltreatment and maternal problems [98, 99]. Lyons-Ruth and colleagues [100] found that maternal withdrawal at 18 months predicted borderline symptoms in late adolescence. Similarly, Carlson and colleagues [101] found prospective relationships between early adversity, including attachment disorganization and parental hostility, and BPD features in middle childhood, early adolescence and adulthood, mediated by impairments in self-representation. These findings also point to the importance of the social context and social inequality in particular. Wilkinson and Pickett [102], for example, have provided substantial evidence that countries with the highest levels of income inequality also manifest the highest levels of mental health and social problems that are closely associated with BPD, such as substance abuse and teenage births.

Psychological mechanisms

Studies assessing the emotional responsiveness of BPD patients in the daily flow of life have found an overall heightened affective instability of patients compared with healthy controls (for an overview, see [103]). However, affective instability is not specific to BPD and has also been found in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder and binge eating disorder [103]. Social emotions such as shame, guilt, disgust, and fear of social rejection seem to be central in the phenomenology of BPD in adults [104] and may give rise to marked dissociative symptoms, which in turn are related to hypoalgesia [105, 106]. Similar findings have been reported in adolescents with BPD [107].

Experimental research has considerably increased our insights into the relationship between these emotional patterns and interpersonal problems by studying interactional behaviour in standardized situations within distinct social domains. The domains of social rejection sensitivity, provocation of aggressive behaviour, and inability to become involved in trustful and cooperative behaviour stand out as particularly important (for a review, see [108]). In adult BPD patients, the experience of being socially excluded—mainly under experimental conditions [109]—leads to distorted perceptions of others, as expressed in feelings such as contempt, resentment and anger towards others [110, 111]. Similar to findings in adults, a recent study in adolescent BPD patients found that, compared with normal controls, they experienced negative emotions more intensely in a social exclusion paradigm; however, there were no differences in their pattern of responding [112]. Impairments in social cognition and mentalizing in particular have been linked to each of the core features of BPD. Mentalizing (or mentalization) refers to the capacity to understand the self and others in terms of intentional mental states, such as feelings, desires, goals and values, which enables individuals to navigate the social world effectively [34]. Studies in adult BPD patients suggest a tendency to judge positive and neutral social cues as more negative [113]. This goes with impairments in tasks requiring more in-depth processing of the intentions and emotions of others (for a review, see [34]). A similar pattern of hypersensitivity to negative faces and problems with disengaging from threatening social information has been observed in adolescents with BPD [114–116]. However, not all studies have confirmed these findings, with some studies reporting similar [117] and even inferior [118] sensitivity to emotional expressions. Although methodological issues may in part explain these divergent findings, the notable heterogeneity of BPD (e.g. regarding trauma history) might also be relevant here (for a review, see [34]).

Further, from a neurobiological perspective, adolescence is characterized by synaptogenesis (i.e. an increase in the number of neural connections in the brain) followed by synaptic pruning, which by early adulthood leads to more efficient brain networks, as well as axonal myelination, which increases the efficiency of neural transmission [119]. Brain areas involved in mentalizing and affect regulation (e.g. the prefrontal cortex and superior temporal cortex) undergo major structural reorganization during adolescence, which seriously impairs mentalizing capacities in adolescence. The experience of peer group rejection, in combination with the adverse childhood experience that is typical of many BPD patients (see below), may have serious consequences for brain maturation in the late adolescent phase, as has recently been demonstrated in animal models [120]. Studies suggest that these neurobiological alterations are expressed not necessarily in terms of a lack of mentalizing, but rather in terms of hypermentalizing, that is, excessive or overinterpretive mentalizing [60].

Evidence-based treatments

Although effective interventions are available for adults, there are few studies on interventions specifically for adolescents with BPD. This is a missed opportunity, because adolescence is a key period for intervention, due to the flexibility and malleability of BPD traits in youth [41]. While early intervention in full-syndrome BPD is now considered crucial for adolescents, adolescent BPD symptoms may also serve as a potential target for indicated prevention of BPD, since personality traits tend to be more flexible during this age period, and early intervention may prevent the negative consequences of chronic BPD (e.g. repetitive trauma, polypharmacy, etc.) [41].

In this section, we discuss the available studies, which in general show that adolescent BPD features respond to intervention. All treatment models are based on evidence-based treatment models for adults with BPD that have been tailored to make them more appropriate for adolescents, for example, by involving parents in treatment. In a meta-analysis reviewing treatment for BPD in adults, characteristics such as the treatment model or treatment setting did not explain between-study heterogeneity [121]. Hence, in reviewing the current knowledge about this topic, we also consider evidence-based aspects of routine clinical care.

Early interventions

Two programmes have been developed as early interventions that target both subsyndromal borderline pathology and syndromal BPD in adolescents. These programmes have broad inclusion criteria (with limited exclusions for co-occurring psychopathology, as this is common in BPD) and are time-limited, with treatments typically lasting 4–6 months.

Emotion regulation training (ERT) [122] is a manual-based group training for adolescents with BPD traits, developed as an add-on to treatment as usual (TAU). ERT focuses on problems in emotion regulation, using the structure of Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) [123] complemented with elements of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT; see later) skills training and cognitive-behavioural therapy. Schuppert et al. [124] compared ERT to TAU in a multisite study that involved 109 adolescents with BPD (73 %) or subthreshold BPD (27 %), but were unable to demonstrate an additional effect of ERT over TAU.

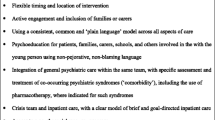

Helping Young People Early (HYPE) [44] consists of a team-based, integrated intervention that includes assertive ‘psychologically informed’ case management, active engagement of families or carers, general psychiatric care (including assessment and treatment of comorbid psychiatric syndromes), capacity for outreach care in the community, crisis team and brief inpatient care, access to a psychosocial recovery programme, individual and group supervision of staff, and a quality insurance programme. All treatment elements are embedded within a psychotherapeutic framework of cognitive analytic therapy (CAT). CAT is a collaborative therapeutic model, with a focus on understanding the individual’s problematic relationship patterns acquired throughout early and subsequent development and the thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that result from these patterns.

In an RCT [125], both CAT and manualized ‘good clinical care’ (GCC) within the comprehensive HYPE service model were effective in reducing psychopathology and parasuicidal behaviour and improving the global functioning of adolescents with subsyndromal or full-syndrome BPD. Both groups showed substantial clinical improvement, and no significant differences were found between the outcomes of the treatment groups at 24 months, although patients allocated to HYPE + CAT seemed to improve more rapidly. In both groups, the number of behavioural problems, depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms was reduced by half. BPD symptoms dropped by the equivalent of one DSM-IV criterion over 24 months. The prevalence of parasuicidal behaviour decreased from 76 % of members in the CAT group and 68 % of the GCC group at baseline to 31 and 33 %, respectively, at 24 months. Social and occupational functioning improved from ‘moderate’ difficulties at the start of the trial to ‘slight’ difficulties at 24 months.

In a quasi-experimental study, Chanen et al. [126] compared the effectiveness of the HYPE (CAT + GCC) comprehensive service model with TAU in the same service setting prior to the implementation of HYPE (historical TAU; H-TAU). Participants had between 2 and 8 BPD criteria, with a mean of 4.4 in the CAT sample and 4.1 in H-TAU. Thirty-nine percent of participants in the CAT sample and 34.4 % in H-TAU had a current BPD diagnosis. Follow-up at 24 months showed that HYPE was more effective than H-TAU and achieved faster rates of improvement for both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, and lower levels of psychopathology, compared to H-TAU. HYPE (GCC) had a better rate of improvement in general functioning (0.49 SDs).

Treatments aimed at self-harm and suicidality

Adaptations of two further, more time-intensive, interventions, DBT and mentalization-based treatment (MBT), have been developed for adolescents with the most concerning BPD symptoms, namely self-harm and suicidality.

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) [127] is a cognitive-behavioural treatment that makes use of change and acceptance techniques within a dialectical framework. DBT was originally developed for chronically suicidal adults with BPD. In DBT, BPD is conceptualized primarily as a disorder of emotion regulation. Different formats have been developed (e.g. [128]) to make DBT more developmentally appropriate for adolescents and their families, by involving parents and families more, reducing the length of the therapy, reducing the number of skills taught, and adding an adolescent-specific skills module focusing on finding a balance between validation and change in adolescent–family dilemmas. McPherson and colleagues [129] reviewed 18 studies on DBT with adolescents with different psychiatric disorders and found that, when compared to TAU, DBT for adolescents with BPD was associated with significant reductions in inpatient hospitalizations, attrition, and behavioural incidents. Recently, a randomized trial of 77 adolescents with repetitive self-harm treated in the community was reported from Norway [59]. A relatively brief treatment of 19 weeks combining individual therapy with multifamily training and family therapy sessions as well as telephone coaching achieved medium-to-large effect sizes relative to usual care in terms of reducing suicidal ideation, depression and borderline symptoms, although it remains to be seen whether these are maintained at follow-up. Overall, different studies, predominantly conducted with females in outpatient or community clinic settings, show promising effects for adolescents with BPD symptoms plus suicidal ideation, suicidal behaviour and/or NSSI. McPherson and colleagues’ review [129] showed improvements in suicidal ideation and behaviour, NSSI, thoughts of NSSI, BPD symptoms, depressive symptoms, hopelessness, dissociative symptoms, anger, overall psychiatric symptoms, general functioning and psychosocial adjustment. Although these effects are promising, more definitive evidence for efficacy of DBT, with adequate randomization and follow-up, is needed. Studies are underway, for example, the Collaborative Adolescent Research on Emotions and Suicide (CARES) study of Marsha Linehan and colleagues [130].

Mentalization-based treatment (MBT) [131, 132] is based on psychodynamic psychotherapy and attachment theory. As noted earlier, mentalization refers to the ability to understand and predict subjective states and mental processes, such as thoughts and feelings, in oneself and in others. Patients with BPD are considered to have a fragile mentalizing capacity, which makes them vulnerable in interpersonal relationships. MBT aims at the recovery of mentalizing in order to help patients regulate their thoughts and feelings, to promote functioning in relationships and self-regulation [133]. The MBT-A programme developed specifically for adolescents consists of weekly individual sessions for 12 months, combined with monthly family sessions (MBT-F) aimed at improving the family’s ability to mentalize, particularly in the context of family conflict [134].

In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Rossouw and Fonagy [134] compared MBT-A with TAU in 80 adolescents presenting to mental health services with self-harm within the prior month, of whom 73 % met DSM-IV criteria for BPD. MBT-A was found to be more effective than TAU in decreasing self-harm and depressive symptoms. The effects of treatment on self-harm were mediated by an increased ability to mentalize and a decrease in attachment avoidance. Although recovery from self-harm was not complete in either group, MBT-A had a higher self-harm recovery rate than TAU, based on both self-report instruments (MBT-A 44 % versus TAU 17 %) and interview-based assessment (57 versus 32 %). A reduction of BPD diagnoses and traits was found in the MBT-A group at the end of treatment, in line with studies on MBT in adults. No specific results on general functioning were reported. Preliminary findings from a 6-month follow-up reported that treatment effects were maintained [135].

More recently, a naturalistic pilot study [136] investigated the feasibility and effectiveness of inpatient MBT-A in 11 female adolescents with borderline symptoms. MBT-A was associated with significant decreases in symptoms and improvements in personality functioning and quality of life 1 year after the start of treatment, with medium-to-large effect sizes (d = 0.58 − 1.46). Ten of the adolescents (91 %) showed reliable change on the Brief Symptom Inventory, and two (18 %) moved to the functional range on this instrument. RCT studies are underway.

Pharmacotherapy

Observational studies of inpatient and outpatient adolescents with BPD report high levels of psychotropic treatment use, with the prescription of psychotropic drugs being primarily symptom-orientated [137, 138]. However, as evidence concerning the efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of adolescents with BPD is sparse, a cautious stance should be adopted in the use of medications and limited to the treatment of co-occurring disorders [139]. In a review, Biskin [139] identified two observational studies on pharmacotherapy, both with many limitations. The review concludes that because of numerous risks and side effects of these treatments, it is strongly advisable to avoid pharmacotherapy in this population [139].

In a small double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT, Amminger et al. [140] investigated whether omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), given as capsules of a fish oil supplement, improved psychosocial functioning and psychopathology in 15 adolescents with BPD who also met ultra-high risk criteria for psychosis. After a 12-week intervention, omega-3 PUFAs significantly improved functioning and reduced psychiatric symptoms compared with placebo. The authors conclude that omega-3 PUFAs should be further explored as a treatment strategy for adolescents with BPD.

In view of the limited studies that currently exist on this subject, the effects of pharmacotherapy need to be further explored before recommendations can be made. On the basis of evidence from adult studies [17], clinicians should be cautious in recommending the use of pharmacotherapy (especially second-generation antipsychotics) as a primary treatment for adolescents.

Summary

Although data are still limited, early results on the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic treatments for BPD in adolescents appear relatively promising. The data from the different studies gathered in this expert review support the view that specialized intervention or treatment for BPD may be more effective than TAU, although methodological limitations of the studies and small effect sizes should dictate caution. In view of the variation in symptomatology and diagnosis in existing study populations, perhaps future studies should recruit on the basis of BPD criteria or BPD features, as opposed to a single diagnostic criterion (e.g., self-harm); in addition, outcome measures should focus more clearly on recovery or partial remission.

Although there are no data supporting the value of family interventions specifically in adolescent BPD, we want to state the clinical importance of working with the family in the treatment of an adolescent with BPD. In the reviewed treatment models, family members are actively engaged, for example, in family therapy, psychoeducation and other forms of family intervention. Evidence for the additional effects of family intervention is needed. Early studies reported problems with retention of adolescents in treatment, and clinical experience confirms that keeping adolescents and their families in treatment for long enough to be able to provide an effective dose of treatment is an important challenge for the field.

In sum, based on the extant research findings, psychosocial treatment appears to be the treatment of choice, as indicated in many guidelines for the treatment of patients with BPD.

Discussion

BPD in adolescents can and should be diagnosed when appropriate. The diagnosis has moderate stability, particularly when assessed dimensionally, and is closely linked with repetitive NSSI and chronic suicidal behaviour. As in adults, BPD in adolescents has complex comorbidity and many individuals are seen in different clinical contexts for a range of conditions before a diagnosis is arrived at. Earlier identification and treatment of these young people is needed as it is likely to have a positive influence on the prognosis of the disorder. Whilst the genetic underpinnings of BPD in adolescence are unequivocal, it is quite likely that this indexes a vulnerability for various kinds of psychosocial distress. The emerging findings on brain structural anomalies in adults with BPD have been only partially replicated in adolescents, suggesting an unfolding developmental neurobiological course. Similarly, impairments in brain connectivity and the neurobiological stress response found in adults with BPD have also been shown in adolescents. The environmental influences upon BPD in adolescence are clear, although no single stressor has been identified as uniquely associated with BPD. BPD is therefore most likely associated with a host of negative environmental factors, ranging from neglect and abuse in close relationships to a broader difficult and invalidating environment. Similarly, affective instability, rejection sensitivity and obvious difficulties in being involved in trustful, cooperative behaviour characterize adolescent BPD. Adverse environmental factors may interact with brain development, leading to persistent dysfunctional social cognitions.

The malleability of social and neurological development of adolescents presents an opportunity for early and potentially preventive intervention. A number of evidence-based therapeutic modalities for adult BPD have been successfully extended to adolescents, including DBT, MBT, CAT and ERT. A specifically adolescent-focused programme, HYPE, based on CAT, promises to be a comprehensive model for addressing a range of adolescent-specific issues alongside target symptoms addressed by adult-oriented programmes. Although HYPE, DBT for adolescents and MBT-A include treatment components for families, the current literature lacks evaluations of family-based interventions.

In the light of our review, we would like to make the following recommendations for future studies and clinical practice.

First, with regard to diagnosis and assessment of personality disorder in adolescents, future research should incorporate a staging theory of BPD distinguishing early precursors and early manifestations of BPD symptoms, including developmentally adapted criteria for young and older adolescents [141]. Diagnosis of BPD should also integrate dimensional factors (as identified in factor analytic studies) alongside categorical DSM/ICD diagnostic criteria, including further research on the promising alternative model for personality disorders presented in Section III of DSM-5 [12, p. 761], which emphasizes impairments in self and relatedness as dimensional core features of personality disorders. As in other diagnostic domains of child and adolescent psychiatry, the use of multiple informants and a comprehensive evaluation of contextual factors and of individual behavioural, cognitive and emotional characteristics, focusing on strengths and resources for change alongside difficulties, is essential to assess the personality fully and plan treatment [142].

Second, in terms of basic research, studies are needed that allow a reliable discrimination of ‘real’ BPD from the so-called ‘storm and stress’ of adolescence, that is, differentiating normal neural development from changes associated with the emergence of symptoms of BPD. In the course of these studies, we may identify a clinically more useful nosology for BPD, including adaptations of the prototype approach to BPD [12], and greater emphasis on the absence of resilience (as opposed to the presence of specific pathology) as a vulnerability factor for severe personality disorder [143].

Finally, with regard to intervention, the development of more efficient (i.e. shorter and more effective) and phase-specific interventions is needed, with long-term follow-up to identify those interventions with the greatest impact on the long-term life course of young people diagnosed with BPD. Although we anticipate that future evidence will confirm the value and efficiency of early intervention, as has been shown to be the case for psychotic illnesses [144], more work in this area is urgently needed. Adaptations of adult models of treatment for adolescent populations have identified the need to pay greater attention to the preferences of adolescents in decisions concerning their treatment, to increase the acceptability of interventions, than may routinely be the case for adult patients [145]. In this context we also wish to emphasize the importance of incorporating a social psychiatric perspective in treatment planning for young people with BPD. Key targets for intervention should include educational goals, work readiness, independence and addressing relationship problems with the young person’s family. From this perspective, involving the social context of young people and treating them in the context of their ‘eco-system’ may be as—or more—important as addressing troubling behaviour such as self-harm or other symptoms of BPD.

To conclude, it is clear that BPD is a social disorder with biological correlates including genetic causation and neurobiological anomalies, but against the background of profoundly disturbed interpersonal relationships. The social reality of BPD is one of interpersonal distress for the sufferer and the family alike. Given the absence of effective pharmacotherapies, effective intervention must start by addressing the immediate social challenges young people with BPD experience. Their social isolation and the challenges encountered by their families both deserve our sympathy and require our urgent empathic help. It is regrettable that the profession has thus far failed to respond to their legitimate needs.

References

Laurenssen EM, Hutsebaut J, Feenstra DJ, Van Busschbach JJ, Luyten P (2013) Diagnosis of personality disorders in adolescents: a study among psychologists. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 7:3. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-7-3

Griffiths M (2011) Validity, utility and acceptability of borderline personality disorder diagnosis in childhood and adolescence: survey of psychiatrists. Psychiatrist 35:19–22. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.109.028779

Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Skodol AE (2014) Course and outcome. In: Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS (eds) Textbook of personality disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington DC, pp 165–186

Soeteman DI, Verheul R, Delimon J, Meerman AM, van den Eijnden E, Rossum BV, Ziegler U, Thunnissen M, Busschbach JJ, Kim JJ (2010) Cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy for cluster B personality disorders. Br J Psychiatry 196:396–403. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.070482

Soeteman DI, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Verheul R, Busschbach JJ (2008) The economic burden of personality disorders in mental health care. J Clin Psychiatry 69:259–265

Feenstra DJ, Hutsebaut J, Laurenssen EM, Verheul R, Busschbach JJ, Soeteman DI (2012) The burden of disease among adolescents with personality pathology: quality of life and costs. J Pers Disord 26:593–604. doi:10.1521/pedi.2012.26.4.593

Bondurant H, Greenfield B, Tse SM (2004) Construct validity of the adolescent borderline personality disorder: a review. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev 13:53–57

Miller AL, Muehlenkamp JJ, Jacobson CM (2008) Fact or fiction: diagnosing borderline personality disorder in adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev 28:969–981. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.004

Bleiberg E (1994) Borderline disorders in children and adolescents: the concept, the diagnosis, and the controversies. Bull Menn Clin 58:169–196

Crockett LJ, Crouter AC (2014) Pathways through adolescence: Individual development in relation to social contexts. Psychology Press, New York

Tackett JL, Sharp C (2014) A developmental psychopathology perspective on personality disorder: introduction to the special issue. J Pers Disord 28:1–4. doi:10.1521/pedi.2014.28.1.1

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington

World Health Organization (1993) The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. World Health Organization, Geneva

Chanen AM, Jovev M, McCutcheon LK, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD (2008) Borderline personality disorder in young people and the prospects for prevention and early intervention. Curr Psychiatry Rev 4:48–57. doi:10.2174/157340008783743820

Kaess M, Brunner R, Chanen A (2014) Borderline personality disorder in adolescence. Pediatrics 134:782–793. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3677

Westen D, DeFife JA, Malone JC, DiLallo J (2014) An empirically derived classification of adolescent personality disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:528–549. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.030

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) Borderline personality disorder: treatment and management. Clinical guideline 78. The British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists, Leicester and London

Bohus M, Buchheim P, Doering S, Herpertz S, Kapfhammer H, Linden M, Müller-Isberner R, Renneberg B, Saß H, Schmitz B, Schweiger U, Resch F, Tress W (2008) S2 Praxisleitlinien in Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie. Band 1 Behandlungsleitlinie Persönlichkeitsstörungen. Steinkopff Verlag, Berlin

Landelijk Kenniscentrum Kinder- en Jeugdpsychiatrie (2011) Borderline persoonlijkheidsstoornis bij adolescenten. Landelijk Kenniscentrum Kinder- en Jeugdpsychiatrie, Utrecht. http://www.kenniscentrum-kjp.nl/Professionals/Stoornissen/Borderline-persoonlijkheidsstoornis/Omschrijving-2. Accessed 13 Nov 2014

Landelijke Stuurgroep Multidisciplinaire Richtlijnontwikkeling in de GGZ (2008) Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn Persoonlijkheidsstoornissen. Richtlijn voor de diagnostiek en behandeling van volwassen patiënten met een persoonlijkheidsstoornis. Trimbos-instituut, Utrecht

National Health and Medical Research Council (2012) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Borderline Personality Disorder. NHMRC, Canberra. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/mh25_borderline_personality_guideline.pdf

Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Velez CN, Schwab-Stone M, Siever LJ, Shinsato L (1993) Prevalence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorders in a community-based survey of adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 150:1237–1243

Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Allot KA, Clarkson V, Yuen HP (2004) Two-year stability of personality disorder in older adolescent outpatients. J Pers Disord 18:526–541. doi:10.1521/pedi.18.6.526.54798

Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D, McDougall E, Yuen HP, Rawlings D, Jackson HJ (2008) Screening for borderline personality disorder in outpatient youth. J Pers Disord 22:353–364. doi:10.1521/pedi.2008.22.4.353

Grilo CM, Becker DF, Fehon DC, Walker ML, Edell WS, McGlashan TH (1996) Gender differences in personality disorders in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 153:1089–1091

Chanen AM, McCutcheon LK, Jovev M, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD (2007) Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder. Med J Aust 187:18–21

Crawford TN, Cohen P, Brook JS (2001) Dramatic-erratic personality disorder symptoms: II. Developmental pathways from early adolescence to adulthood. J Pers Disord 15:336–350. doi:10.1521/pedi.15.4.336.19185

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR (2003) The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 160:274–283

Sharp C, Romero C (2007) Borderline personality disorder: a comparison between children and adults. Bull Menn Clin 71:85–114. doi:10.1521/bumc.2007.71.2.85

Kaess M, von Ceumern-Lindenstjerna IA, Parzer P, Chanen A, Mundt C, Resch F, Brunner R (2013) Axis I and II comorbidity and psychosocial functioning in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology 46:55–62. doi:10.1159/000338715

Lawrence KA, Allen JS, Chanen AM (2011) A study of maladaptive schemas and borderline personality disorder in young people. Cogn Ther Res 35:30–39. doi:10.1007/s10608-009-9292-4

Becker DF, Grilo CM, Edell WS, McGlashan TH (2002) Diagnostic efficiency of borderline personality disorder criteria in hospitalized adolescents: comparison with hospitalized adults. Am J Psychiatry 159:2042–2047

Westen D, Betan E, Defife JA (2011) Identity disturbance in adolescence: associations with borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol 23:305–313. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000817

Fonagy P, Luyten P (2015) A multilevel perspective on the development of borderline personality disorder. In: Cicchetti D (ed) Development and psychopathology. Wiley, New York (in press)

Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F (2011) Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 377:74–84. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61422-5

Mattanah JJ, Becker DF, Levy KN, Edell WS, McGlashan TH (1995) Diagnostic stability in adolescents followed up 2 years after hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry 152:889–894

Crawford TN, Cohen P, Brook JS (2001) Dramatic-erratic personality disorder symptoms: I. Continuity from early adolescence into adulthood. J Pers Disord 15:319–335. doi:10.1521/pedi.15.4.319.19182

Stepp SD, Pilkonis PA, Hipwell AE, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M (2010) Stability of borderline personality disorder features in girls. J Pers Disord 24:460–472. doi:10.1521/pedi.2010.24.4.460

Nock MK, Joiner TE Jr, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ (2006) Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res 144:65–72. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010

Muehlenkamp JJ, Ertelt TW, Miller AL, Claes L (2011) Borderline personality symptoms differentiate non-suicidal and suicidal self-injury in ethnically diverse adolescent outpatients. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52:148–155. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02305.x

Chanen AM, McCutcheon L (2013) Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder: current status and recent evidence. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 54:24–29. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119180

Aviram RB, Brodsky BS, Stanley B (2006) Borderline personality disorder, stigma, and treatment implications. Harv Rev Psychiatry 14:249–256. doi:10.1080/10673220600975121

Rusch N, Holzer A, Hermann C, Schramm E, Jacob GA, Bohus M, Lieb K, Corrigan PW (2006) Self-stigma in women with borderline personality disorder and women with social phobia. J Nerv Ment Dis 194:766–773. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000239898.48701.dc

Chanen AM, McCutcheon LK, Germano D, Nistico H, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD (2009) The HYPE Clinic: an early intervention service for borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract 15:163–172. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000351876.51098.f0

First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Smith Benjamin L (1997) User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC

Loranger AW (1999) International personality disorder examination: DSM-IV and ICD-10 interviews. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa

Chanen AM, Jovev M, Jackson HJ (2007) Adaptive functioning and psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 68:297–306

Henze R, Barth J, Parzer P, Bertsch K, Schmitt R, Lenzen C, Herpertz S, Resch F, Brunner R, Kaess M (2013) Validierung eines Screening-Instruments zur Borderline-Personlichkeitsstorung im Jugend- und jungen Erwachsenenalter—Gutekriterien und Zusammenhang mit dem Selbstwert der Patienten. [Validation of a screening instrument for borderline personality disorder in adolescents and young adults—psychometric properties and association with the patient’s self-esteem.] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 81:324–330. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1335408

Kaess M, Resch F, Parzer P, von Ceumern-Lindenstjerna IA, Henze R, Brunner R (2013) Temperamental patterns in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 201:109–115. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827f6480

Zanarini MC (2003) The Childhood Interview for DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder (CI-BPD). McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Belmont

Sharp C, Ha C, Michonski J, Venta A, Carbone C (2012) Borderline personality disorder in adolescents: evidence in support of the Childhood Interview for DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder in a sample of adolescent inpatients. Compr Psychiatry 53:765–774. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.12.003

van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2005) Informant, gender and age differences in ratings of adolescent problem behaviour. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 14:117–126. doi:10.1007/s00787-005-0438-y

Schuppert HM, Bloo J, Minderaa RB, Emmelkamp PM, Nauta MH (2012) Psychometric evaluation of the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index-IV–adolescent version and parent version. J Pers Disord 26:628–640. doi:10.1521/pedi.2012.26.4.628

Kaess M (2014) Diagnosing PD in adolescence—current dilemmas and challenges. ESSPD Newsletter 3:2–4

Poreh AM, Rawlings D, Claridge G, Freeman JL, Faulkner C, Shelton C (2006) The BPQ: a scale for the assessment of borderline personality based on DSM-IV criteria. J Pers Disord 20:247–260. doi:10.1521/pedi.2006.20.3.247

Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, Boulanger JL, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J (2003) A screening measure for BPD: the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord 17:568–573

Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, Berger P, Buchheim P, Channabasavanna SM, Coid B, Dahl A, Diekstra RF, Ferguson B, Jacobsberg LB, Mombour W, Pull C, Ono Y, Regier DA (1994) The International Personality Disorder Examination. The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51:215–224

Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, Stieglitz RD, Domsalla M, Chapman AL, Steil R, Philipsen A, Wolf M (2009) The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology 42:32–39. doi:10.1159/000173701

Mehlum L, Tormoen AJ, Ramberg M, Haga E, Diep LM, Laberg S, Larsson BS, Stanley BH, Miller AL, Sund AM, Groholt B (2014) Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:1082–1091. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.003

Sharp C, Mosko O, Chang B, Ha C (2011) The cross-informant concordance and concurrent validity of the Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children in a community sample of boys. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 16:335–349. doi:10.1177/1359104510366279

Chang B, Sharp C, Ha C (2011) The criterion validity of the Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children in an adolescent inpatient setting. J Pers Disord 25:492–503. doi:10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.492

Speranza M, Revah-Levy A, Cortese S, Falissard B, Pham-Scottez A, Corcos M (2011) ADHD in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry 11:158. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-158

Loas G, Pham-Scottez A, Cailhol L, Perez-Diaz F, Corcos M, Speranza M (2013) Axis II comorbidity of borderline personality disorder in adolescents. Psychopathology 46:172–175. doi:10.1159/000339530

Ha C, Balderas JC, Zanarini MC, Oldham J, Sharp C (2014) Psychiatric comorbidity in hospitalized adolescents with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 75:457–464. doi:10.4088/JCP.13m08696

Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Keyes KM, Skodol AE, Markon KE, Grant BF, Hasin DS (2011) Borderline personality disorder co-morbidity: relationship to the internalizing-externalizing structure of common mental disorders. Psychol Med 41:1041–1050. doi:10.1017/S0033291710001662

Stepp SD, Burke JD, Hipwell AE, Loeber R (2012) Trajectories of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms as precursors of borderline personality disorder symptoms in adolescent girls. J Abnorm Child Psychol 40:7–20. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9530-6

Nigg JT, Silk KR, Stavro G, Miller T (2005) Disinhibition and borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol 17:1129–1149. doi:10.1017/S0954579405050534

Distel MA, Willemsen G, Ligthart L, Derom CA, Martin NG, Neale MC, Trull TJ, Boomsma DI (2010) Genetic covariance structure of the four main features of borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 24:427–444. doi:10.1521/pedi.2010.24.4.427

Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, Choi-Kain LW, Mitchell KS, Jang KL, Hudson JI (2011) Family study of borderline personality disorder and its sectors of psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:753–762. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.65

Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Ystrom E, Neale MC, Aggen SH, Mazzeo SE, Knudsen GP, Tambs K, Czajkowski NO, Kendler KS (2013) Structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for symptoms of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 70:1206–1214. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1944

Michonski JD, Sharp C, Steinberg L, Zanarini MC (2013) An item response theory analysis of the DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria in a population-based sample of 11- to 12-year-old children. Personal Disord 4:15–22. doi:10.1037/a0027948

Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, McGue M (2009) Stability, change, and heritability of borderline personality disorder traits from adolescence to adulthood: a longitudinal twin study. Dev Psychopathol 21:1335–1353. doi:10.1017/S0954579409990186

Distel MA, Trull TJ, Derom CA, Thiery EW, Grimmer MA, Martin NG, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI (2008) Heritability of borderline personality disorder features is similar across three countries. Psychol Med 38:1219–1229. doi:10.1017/S0033291707002024

Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Czajkowski N, Roysamb E, Tambs K, Torgersen S, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T (2008) The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for DSM-IV personality disorders: a multivariate twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65:1438–1446. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1438

Torgersen S, Lygren S, Oien PA, Skre I, Onstad S, Edvardsen J, Tambs K, Kringlen E (2000) A twin study of personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 41:416–425. doi:10.1053/comp.2000.16560

Hankin BL, Barrocas AL, Jenness J, Oppenheimer CW, Badanes LS, Abela JR, Young J, Smolen A (2011) Association between 5-HTTLPR and borderline personality disorder traits among youth. Front Psychiatry 2:6. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00006

Belsky DW, Caspi A, Arseneault L, Bleidorn W, Fonagy P, Goodman M, Houts R, Moffitt TE (2012) Etiological features of borderline personality related characteristics in a birth cohort of 12-year-old children. Dev Psychopathol 24:251–265. doi:10.1017/S0954579411000812

Ruocco AC, Amirthavasagam S, Zakzanis KK (2012) Amygdala and hippocampal volume reductions as candidate endophenotypes for borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Psychiatry Res 201:245–252. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.02.012

Brunner R, Henze R, Parzer P, Kramer J, Feigl N, Lutz K, Essig M, Resch F, Stieltjes B (2010) Reduced prefrontal and orbitofrontal gray matter in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder: is it disorder specific? NeuroImage 49:114–120. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.070

Chanen AM, Velakoulis D, Carison K, Gaunson K, Wood SJ, Yuen HP, Yucel M, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Pantelis C (2008) Orbitofrontal, amygdala and hippocampal volumes in teenagers with first-presentation borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 163:116–125. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.08.007

Whittle S, Chanen AM, Fornito A, McGorry PD, Pantelis C, Yucel M (2009) Anterior cingulate volume in adolescents with first-presentation borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 172:155–160. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.12.004

Goodman M, Hazlett EA, Avedon JB, Siever DR, Chu KW, New AS (2011) Anterior cingulate volume reduction in adolescents with borderline personality disorder and co-morbid major depression. J Psychiatr Res 45:803–807. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.11.011

Richter J, Brunner R, Parzer P, Resch F, Stieltjes B, Henze R (2014) Reduced cortical and subcortical volumes in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 221:179–186. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.01.006

Jovev M, Whittle S, Yucel M, Simmons JG, Allen NB, Chanen AM (2014) The relationship between hippocampal asymmetry and temperament in adolescent borderline and antisocial personality pathology. Dev Psychopathol 26:275–285. doi:10.1017/S0954579413000886

Maier-Hein KH, Brunner R, Lutz K, Henze R, Parzer P, Feigl N, Kramer J, Meinzer HP, Resch F, Stieltjes B (2014) Disorder-specific white matter alterations in adolescent borderline personality disorder. Biol Psychiatry 75:81–88. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.03.031

New AS, Carpenter DM, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Ripoll LH, Avedon J, Patil U, Hazlett EA, Goodman M (2013) Developmental differences in diffusion tensor imaging parameters in borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res 47:1101–1109. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.03.021

Goodman M, Mascitelli K, Triebwasser J (2013) The neurobiological basis of adolescent-onset borderline personality disorder. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22:212–219

New AS, Goodman M, Triebwasser J, Siever LJ (2008) Recent advances in the biological study of personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 31:441–461. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2008.03.011

Plener PL, Bubalo N, Fladung AK, Ludolph AG, Lule D (2012) Prone to excitement: adolescent females with non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) show altered cortical pattern to emotional and NSS-related material. Psychiatry Res 203:146–152. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.12.012

Wingenfeld K, Spitzer C, Rullkotter N, Lowe B (2010) Borderline personality disorder: hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis and findings from neuroimaging studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35:154–170. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.09.014

Zimmerman DJ, Choi-Kain LW (2009) The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in borderline personality disorder: a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry 17:167–183. doi:10.1080/10673220902996734

Nater UM, Bohus M, Abbruzzese E, Ditzen B, Gaab J, Kleindienst N, Ebner-Priemer U, Mauchnik J, Ehlert U (2010) Increased psychological and attenuated cortisol and alpha-amylase responses to acute psychosocial stress in female patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35:1565–1572. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.06.002

Kaess M, Hille M, Parzer P, Maser-Gluth C, Resch F, Brunner R (2012) Alterations in the neuroendocrinological stress response to acute psychosocial stress in adolescents engaging in nonsuicidal self-injury. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37:157–161. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.05.009

Lyons-Ruth K, Choi-Kain L, Pechtel P, Bertha E, Gunderson J (2011) Perceived parental protection and cortisol responses among young females with borderline personality disorder and controls. Psychiatry Res 189:426–432. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.038

Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES (2007) If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychol Bull 133:25–45. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25

Chanen AM, Kaess M (2012) Developmental pathways to borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 14:45–53. doi:10.1007/s11920-011-0242-y

Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes EM, Bernstein DP (1999) Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:600–606. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.600

Cohen P, Chen H, Gordon K, Johnson J, Brook J, Kasen S (2008) Socioeconomic background and the developmental course of schizotypal and borderline personality disorder symptoms. Dev Psychopathol 20:633–650. doi:10.1017/S095457940800031X

Crawford TN, Cohen PR, Chen H, Anglin DM, Ehrensaft M (2009) Early maternal separation and the trajectory of borderline personality disorder symptoms. Dev Psychopathol 21:1013–1030. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000546

Lyons-Ruth K, Bureau JF, Holmes B, Easterbrooks A, Brooks NH (2013) Borderline symptoms and suicidality/self-injury in late adolescence: prospectively observed relationship correlates in infancy and childhood. Psychiatry Res 206:273–281. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.030

Carlson EA, Egeland B, Sroufe LA (2009) A prospective investigation of the development of borderline personality symptoms. Dev Psychopathol 21:1311–1334. doi:10.1017/S0954579409990174

Wilkinson R, Pickett K (2009) The spirit level: why equality is better for everyone. Penguin Books, London

Santangelo P, Bohus M, Ebner-Priemer UW (2014) Ecological momentary assessment in borderline personality disorder: a review of recent findings and methodological challenges. J Pers Disord 28:555–576. doi:10.1521/pedi_2012_26_067

Schmahl C, Herpertz S, Bertsch K, Ende G, Flor H, Kirsch P, Lis S, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Rietschel M, Schneider M, Spanagel R, Treede R-D, Bohus M (2014) Mechanisms of disturbed emotion processing and social interaction in borderline personality disorder: state of knowledge and research agenda of the German Clinical Research Unit. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysreg 1:12. doi:10.1186/2051-6673-1-12

Ludascher P, Bohus M, Lieb K, Philipsen A, Jochims A, Schmahl C (2007) Elevated pain thresholds correlate with dissociation and aversive arousal in patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 149:291–296. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2005.04.009

Stiglmayr CE, Ebner-Priemer UW, Bretz J, Behm R, Mohse M, Lammers CH, Anghelescu IG, Schmahl C, Schlotz W, Kleindienst N, Bohus M (2008) Dissociative symptoms are positively related to stress in borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 117:139–147. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01126.x

Hawes DJ, Helyer R, Herlianto EC, Willing J (2013) Borderline personality features and implicit shame-prone self-concept in middle childhood and early adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 42:302–308. doi:10.1080/15374416.2012.723264

Lis S, Bohus M (2013) Social interaction in borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 15:338. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0338-z

Bungert M, Liebke L, Thome J, Haeussler K, Bohus M, Lis S (2015) Rejection sensitivity and symptom severity in patients with borderline personality disorder: effects of childhood maltreatment and self-esteem. Borderline Personal Disorder Emotion Dysregulation 2:4. doi:10.1186/s40479-015-0025-x

Staebler K, Renneberg B, Stopsack M, Fiedler P, Weiler M, Roepke S (2011) Facial emotional expression in reaction to social exclusion in borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med 41:1929–1938. doi:10.1017/S0033291711000080

Domsalla M, Koppe G, Niedtfeld I, Vollstadt-Klein S, Schmahl C, Bohus M, Lis S (2013) Cerebral processing of social rejection in patients with borderline personality disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. doi:10.1093/scan/nst176

Lawrence KA, Chanen AM, Allen JS (2011) The effect of ostracism upon mood in youth with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 25:702–714. doi:10.1521/pedi.2011.25.5.702

Winter D, Herbert C, Koplin K, Schmahl C, Bohus M, Lis S (2015) Negative evaluation bias for positive self-referential information in borderline personality disorder. PLoS One 10:e0117083. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117083

Jovev M, Green M, Chanen A, Cotton S, Coltheart M, Jackson H (2012) Attentional processes and responding to affective faces in youth with borderline personality features. Psychiatry Res 199:44–50. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.027

von Ceumern-Lindenstjerna IA, Brunner R, Parzer P, Mundt C, Fiedler P, Resch F (2010) Attentional bias in later stages of emotional information processing in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology 43:25–32. doi:10.1159/000255960

von Ceumern-Lindenstjerna IA, Brunner R, Parzer P, Mundt C, Fiedler P, Resch F (2010) Initial orienting to emotional faces in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology 43:79–87. doi:10.1159/000274176

Jovev M, Chanen A, Green M, Cotton S, Proffitt T, Coltheart M, Jackson H (2011) Emotional sensitivity in youth with borderline personality pathology. Psychiatry Res 187:234–240. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.019

Robin M, Pham-Scottez A, Curt F, Dugre-Le Bigre C, Speranza M, Sapinho D, Corcos M, Berthoz S, Kedia G (2012) Decreased sensitivity to facial emotions in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 200:417–421. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.032

Sebastian C, Viding E, Williams KD, Blakemore SJ (2010) Social brain development and the affective consequences of ostracism in adolescence. Brain Cogn 72:134–145. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2009.06.008

Schneider P, Hannusch C, Schmahl C, Bohus M, Spanagel R, Schneider M (2014) Adolescent peer-rejection persistently alters pain perception and CB1 receptor expression in female rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 24:290–301. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.04.004

Barnicot K, Katsakou C, Marougka S, Priebe S (2011) Treatment completion in psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 123:327–338. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01652.x

van Gemert TM, Ringrose HJ, Schuppert HM, Wiersema HM (2009) Emotieregulatietraining (ERT), een programma voor adolescenten met emotieregulatieproblemen. Boom, Amsterdam

Bartels N, Crotty M, Blum N (1997) The borderline personality disorder skill training manual. University of Iowa, Iowa City

Schuppert HM, Timmerman ME, Bloo J, van Gemert TG, Wiersema HM, Minderaa RB, Emmelkamp PM, Nauta MH (2012) Emotion regulation training for adolescents with borderline personality disorder traits: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51(1314–1323):e1312. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.002

Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McCutcheon LK, Jovev M, Dudgeon P, Yuen HP, Germano D, Nistico H, McDougall E, Weinstein C, Clarkson V, McGorry PD (2008) Early intervention for adolescents with borderline personality disorder using cognitive analytic therapy: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 193:477–484. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048934

Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McCutcheon LK, Jovev M, Dudgeon P, Yuen HP, Germano D, Nistico H, McDougall E, Weinstein C, Clarkson V, McGorry PD (2009) Early intervention for adolescents with borderline personality disorder: quasi-experimental comparison with treatment as usual. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 43:397–408. doi:10.1080/00048670902817711

Linehan MM (1993) Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press, New York

Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan MM, Wetzler S, Leigh E (1997) Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. J Practical Psychiatry Behav Health 3:78–86

MacPherson HA, Cheavens JS, Fristad MA (2013) Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents: theory, treatment adaptations, and empirical outcomes. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 16:59–80. doi:10.1007/s10567-012-0126-7

Berk M, Adrian M, McCauley E, Asarnow J, Avina C, Linehan M (2014) Conducting research on adolescent suicide attempters: dilemmas and decisions. Behav Ther (N Y N Y) 37:65–69

Bateman A, Fonagy P (1999) Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 156:1563–1569. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.10.1563

Bateman A, Fonagy P (2008) 8-year follow-up of patients treated for borderline personality disorder: mentalization-based treatment versus treatment as usual. Am J Psychiatry 165:631–638. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040636

Bateman A, Fonagy P (2010) Mentalization based treatment for borderline personality disorder. World Psychiatry 9:11–15

Rossouw TI, Fonagy P (2012) Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51(1304–1313):e1303. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018

Rossouw T (2014) Minding the storms in adolescence. In: Second International Congress of MBT. June 12 to 13, 2014. Haarlem, The Netherlands

Laurenssen EM, Hutsebaut J, Feenstra DJ, Bales DL, Noom MJ, Busschbach JJ, Verheul R, Luyten P (2014) Feasibility of mentalization-based treatment for adolescents with borderline symptoms: a pilot study. Psychotherapy 51:159–166. doi:10.1037/a0033513

Wockel L, Goth K, Matic N, Zepf FD, Holtmann M, Poustka F (2010) Psychopharmakotherapie einer ambulanten und stationaren Inanspruchnahmepopulation adoleszenter Patienten mit Borderline-Personlichkeitsstorung. [Psychopharmacotherapy in adolescents with borderline personality disorder in inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment]. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 38:37–49. doi:10.1024/1422-4917.a000005

Cailhol L, Jeannot M, Rodgers R, Guelfi JD, Perez-Diaz F, Pham-Scottez A, Corcos M, Speranza M (2013) Borderline personality disorder and mental healthcare service use among adolescents. J Pers Disord 27:252–259. doi:10.1521/pedi.2013.27.2.252

Biskin RS (2013) Treatment of borderline personality disorder in youth. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22:230–234