Abstract

Objectives

To assess the quality of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) on screening and diagnosis of oral cancer and to describe the characteristics of their recommendations.

Materials and methods

We systematically searched EMBASE, MEDLINE, CPG’ websites, and dentistry and oncology scientific societies to identify CPGs that were related to screening and diagnosis of oral cancer. The quality of selected CPGs was independently assessed by four appraisers using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument. The inter-appraiser agreement was assessed. We performed a descriptive analysis of the recommendations included in the selected CPGs.

Results

Eight CPGs were selected. The overall agreement among reviewers was considered very good (ICC: 0.823; 95% CI: 0.777–0.861). The median scores of the six AGREE II domains were as follows: “scope and purpose” 97.9% (IQR: 96.2–100.0%); “stakeholder involvement” 86.1% (IQR: 69.8–93.1%); “rigor of development” 75.3% (IQR: 64.2–94.3%); “clarity of presentation” 91.7% (IQR: 82.6–94.4%); “applicability” 53.1% (IQR: 19.3–74.2%); and “editorial independence” 83.3% (IQR: 67.2–93.8%). Four CPGs were assessed as “recommended”, four “recommended with modifications”, and none “not recommended”. Twenty-three recommendations were provided, mostly with a low or very low level of evidence.

Conclusion

The methodological quality of CPGs on screening and diagnosis of oral cancer is moderate. The “applicability” domain scored the lowest. Most recommendations were based on a low o very low level of evidence.

Clinical relevance

Greater efforts are needed to provide healthcare based on high-quality evidence-based CPGs in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to increasing pressure to provide evidence-based medical care, the use of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) has been increasing worldwide over the last decade [1, 2]. CPGs are a summary of evidence-based recommendations that were developed using systematic methods of literature review. These are a very useful tool for the translation of research evidence into practice [3]. By using CPGs based on the best available evidence, healthcare professionals can be assisted in minimizing inappropriate variation in clinical practice, improving decision-making processes on the most suitable healthcare for explicit clinical circumstances, and promoting effective and safe patient outcomes [4]. However, some have reported that many CPGs are lacking quality and that there is a wide vast of heterogeneity among their recommendations [5, 6]. Thus, systematically developed CPGs using the best available evidence to provide transparent recommendations are required.

The appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument is a validated, generic tool to systematically appraise CPG methodological development and quality [7]. In 1988, the AGREE initiative was established by an international group of researchers and CPG developers; the original AGREE instrument was published in 2003, and its update—AGREE II—was released in 2010 [7]. This instrument has become the standard tool for CPG evaluation and development, with the purpose of improving CPG quality and the likelihood of broad endorsement [8].

Currently, oral cavity cancer is considered a public health issue worldwide. Around 600,000 new cases are expected per annum. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common type of oral cancer [9]. While it represents just over 2% of the global cancer incidence, its 50% fatality rate is a major cause of concern [10]. The high mortality rate of oral cancer may be associated with many factors, one the main ones being the diagnostic delay. Commonly, oral suspicious lesions are easy to assess and should be diagnosed early for the therapeutic intervention to be effective [11]. Nonetheless, patients are often diagnosed in advanced stages of disease; this might be due to the lack of consultation, or the barriers in adequate healthcare accessibility [12]. Moreover, the value of screening healthy adults with no symptoms and using several tools for diagnosing oral cancer is uncertain [13]; thus, these issues need to be addressed clearly using reliable and high-quality CPGs.

There are many CPGs on screening and diagnosis of oral cancer; nevertheless, little is known about the quality, applicability, and potential impact of those CPGs, since their quality has not been systematically evaluated. This study belongs to a project that aims to assess the quality of CPGs on oral cancer; the quality of CPGs on therapeutic interventions for oral cancer has been previously reported [14]. This report focuses on quality methodological assessment of CPGs on screening and diagnosis of oral cancer and describes the characteristics of their recommendations.

Materials and methods

We conducted a systematic critical appraisal of the quality and recommendations of CPGs on screening and diagnosis of oral cancer using the AGREE II instrument. The methods used were previously published [14].

Data sources and strategy search

Using search strategies developed by an expert, we systematically searched EMBASE (via Ovid), MEDLINE (via PubMed), CPG’ websites, and dentistry and oncology scientific societies to identify CPGs published between 2006 and 2018. We used key words and terms related to oral cavity tumor and CPGs such as “oral cancer”, “oral tumor”, “oral carcinoma”, “mouth neoplasms”, “buccal carcinoma”, “guideline”, “practice guideline”, “guidance”, and “recommendation”. The last search was conducted on 22 May 2018 (Additional file 1).

CPG identification

Our eligibility criteria were: (i) CPGs providing recommendations for screening, suspicion, or diagnosis of primary oral cavity cancer (all histopathological types of malignancies) in adults; (ii) CPGs about other cancers were selected if they provided at least two clear recommendations for oral cancer; (iii) inclusion of an explicit methods section; and (iv) the most recent version from a CPG developer.

Two authors independently reviewed titles/abstracts and full texts to identify eligible CPGs. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus, if needed, a third author was included in the discussion until a consensus was obtained.

Quality appraisal of CPG

The quality of CPGs was independently assessed by four appraisers using the AGREE II instrument [8, 15], which includes a 23-item checklist rated on a seven-point Likert scale and categorized into the following six domains:

-

Domain 1: Scope and purpose; including the main objectives of the CPGs, the health questions, and the target population.

-

Domain 2: Stakeholder involvement; this focuses on the extent to which the CPG was developed by the appropriate stakeholders and represents the views of its intended users.

-

Domain 3: Rigor of development; describing the process used to synthesize and gather evidence, and the methodology used to formulate and update the recommendations.

-

Domain 4: Clarity and presentation; assessing whether recommendations are explicit and unambiguous, different options for managing the condition or health issue are clearly presented, and key recommendations are easily identifiable.

-

Domain 5: Applicability; dealing with implementation issues, such as the assessment of organizational facilitators and barriers, the development of educational sources, economic implications, and monitoring or audit criteria.

-

Domain 6: Editorial independence; assessing whether the views or interests of the funding sources have influenced the recommendations, and if the conflicts of interest statement reports all information about the CPG developer team.

The AGREE II instrument also includes two overall quality appraisals for each CPG: an overall score of 1 to 7, and whether the reviewer would recommend using the CPG, assessing it as “recommended”, “recommended with modifications”, or “not recommended”.

CPG data extraction

Two authors independently extracted data from each CPG such as: title, country, year of publication, authoring organization, language, level of development, funding source, whether or not it is an update, recommendations, methods used to determine the recommendations, level of evidence, grading of the recommendations, and histological type of oral cancer.

Statistical analysis

Inter-appraiser agreement was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) [16]. We calculated the domain scores by adding up all the scores of the individual items within a domain and calculated the percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain [15]. Standardized scores (range, 0 to 100%) for each domain were calculated as follows: [(obtained score − minimum possible score) / (maximum possible score − minimum possible score)] × 100%. We used 60% as a cut-off point for adequate quality. Median and the interquartile range (IQR: Q1-Q3) were calculated for each domain score for each CPG. Moreover, we performed a descriptive analysis of recommendation included in the selected CPGs. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS® version 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Selection of CPGs

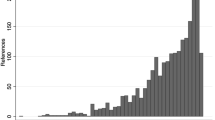

The selection process is presented in Fig. 1. We initially identified 496 records and excluded 433 references after screening titles and abstracts. We reviewed 63 full-text documents and excluded 55 of them (Additional file 2). Finally, we selected eight CPGs [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Characteristics of the selected CPGs

All included CPGs [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] were published in English language. Five CPGs [18,19,20,21,22] included recommendations for oral cancer exclusively, whereas the other three CPGs [17, 23, 24] also included recommendations for other cancers. Four CPGs [17, 19, 20, 22] included recommendations for diagnosis, two CPGs [18, 21] focused on screening and two CPGs [23, 24] focused on suspected oral cancer. Moreover, four CPGs [17, 19, 20, 22] also included recommendations related to processes such as the treatment and management of oral cancer. Five CPGs [17, 19,20,21,22] included recommendations for OSCC, one [17] of them also included recommendations for other histological types of mouth neoplasms, whereas three CPGs [18, 23, 24] did not specify that information. Two CPGs [18, 21] were from USA, two CPGs [17, 23] were from United Kingdom, while the others were one from each of the following: Canada [19], Belgium [20], Germany [22], and New Zealand [24]. Six CPGs [17,18,19,20, 23, 24] were developed by a government agency, three CPGs [18, 21, 23] were an update, only three CPGs [20, 21, 23] used GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) framework to develop their recommendations, and one CPG [19] did not report the level of evidence nor grading of its recommendations (Table 1).

Quality appraisal of CPGs

The overall agreement among reviewers was considered very good (ICC: 0.823; 95% CI: 0.777–0.861). Table 2 represents standardized scores across CPGs by domain, and the overall recommendation for clinical use of the included CPGs.

Scope and purpose

The median score for this domain was 97.4% (IQR: 96.2–100.0%), demonstrating that most CPGs were considered to have an adequate report of this domain. All CPGs [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] (100.0%) scored over 60%.

Stakeholder involvement

The median score for this domain was 86.1% (IQR: 69.8–93.1%). Seven CPGs [17, 18, 20,21,22,23,24] (87.5%) scored over 60%. The main limitation across some CPGs was that, although patients were included in the CPG process, the way the panel included their values and preferences remained unclear.

Rigor of development

The median score for this domain was 75.3% (IQR: 64.2–94.3%). Although all CPGs [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] (100.0%) scored over 60%, three of them [18, 19, 22] (37.5%) scored just above this threshold. Limitations included that it was unclear how some CPGs had assessed the potential harms of the screening and diagnostic recommendations. Moreover, one CPG [19] showed no direct link between the recommendation and the evidence, and there was no formal assessment of the strengths and limitations of the supporting evidence.

Clarity of presentation

The median score for this domain was 91.7% (IQR: 82.6–94.4%), indicating that recommendations were clearly presented. All CPGs [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] (100.0%) scored over 60%.

Applicability

The median score in this domain was 53.1% (IQR: 19.3–88.5%). Only four CPGs [17, 20, 23, 24] (50.0%) scored over 60%. The main limitations were that most CPGs lacked a discussion on their facilitators, and application barriers, and that they failed to assess the implications of use of resources or the auditing criteria.

Editorial independence

The median score in this domain was 83.3% (IQR: 67.2–93.8%). Seven CPGs [17,18,19,20,21, 23, 24] (87.5%) scored over 60%. Some CPGs did not fully describe a declaration about their funding sources and their possible influence on CPG development process or failed to clearly report the potential conflicts of interest of authors or CPG developer.

Overall CPG assessment

Among all CPGs evaluated, four CPGs [17, 20, 21, 23] (50%) were “recommended” by the reviewers; four CPGs [18, 19, 22, 24] (50%) were “recommended with modifications”; and no CPG (0%) was “not recommended”. Almost all CPGs assessed as “recommended” scored over 60% for all domains. The median of overall rate was 6.0 (IQR: 4.6–6.4), the highest score was 7.0 [20], and the lowest one was 4.0 [22].

Recommendation characteristics

Among the selected CPGs [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], one CPG [18] did not provide recommendation because the authors concluded that the current evidence was insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for oral cancer in asymptomatic adults, whereas the other seven CPGs [17, 19,20,21,22,23,24] provided a total of 23 recommendations, most of them having a low or very low level of evidence. Regarding grade of recommendation, three recommendations were reported as strong [20], 16 recommendations were reported as weak [17, 21, 22, 24] (conditional, B, C, D), and four recommendations did not report level of evidence or the grade of recommendation [19, 23] (Table 3). In addition, four CPGs [17, 21, 22, 24] provided 10 good practice points (Table 4).

Discussion

CPGs can be used to optimize clinical practice; however, their assimilation and use will depend on how they are developed. Hence, this study sought to assess the quality of CPGs involving screening and diagnosis oral cancer recommendations, to assist clinicians when selecting appropriate CPGs.

Overall, quality of CPGs on screening and diagnosis of oral cancer is moderate with only 50% of CPGs being assessed as “recommended”. The highest quality CPGs were developed by the Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE) [20], the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) [17], The American Dental Association (ADA) [21], and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [23], scoring over 60% in most domains. However, despite that some of these CPGs were rated as “recommended”, there are aspects that should be considered. For example, although the NICE CPG [23] was developed through a rigorous process, its recommendations neither report the level of evidence nor the strength of recommendations; the ADA CPG [21] scored below the threshold in the applicability domain, because it discussed the implications but there was no assessment of the use of resources nor auditing criteria. Likewise, the SIGN CPG [17] was published 12 years ago; thus, its recommendations are likely to be based on outdated evidence. It has been suggested that CPGs should be updated at 3-year intervals, because new evidence may result in substantial changes to the recommendations [25]. Moreover, we wish to highlight that the recommendations included in these CPGs should be considered with caution, since the AGREE II instrument only assesses the reporting of methodological quality aspects for their development, not judging the rationality of their recommendations.

Half of the included CPGs [18, 19, 22, 24] were assessed as “recommended with modifications”, indicating that there is room for improving their quality if their deficiencies are addressed. Some of the aspects that need to be addressed are: the lack of patient involvement in the CPG development process, the insufficient inclusion of patients’ values and preferences, the lack of direct link between the recommendation and the evidence, and the inadequate assessment of the strengths and limitations of the supporting evidence. Consistently, the methodological quality of CPGs in diverse clinical areas has been reported to be extremely variable, showing a substantial opportunity for improvement [6, 26].

The domain with the highest scores was “scope and purpose”, and the domain with the lowest scores was “applicability”. These results are in accordance with our previous report [14] that assessed the quality of CPGs on therapeutic interventions for oral cancer. However, we would like to highlight that both studies evaluated the same four CPGs [17, 19, 20, 22], which included recommendations for both screening/diagnosis and treatment for oral cavity cancer. Likewise, these findings are similar to some reports in oncology area, specifically in carcinoma of the head and neck [2, 27], as well as dentistry area [28, 29]. These findings are also similar to CPG quality appraisals in other clinical fields [6, 30,31,32]. The fact that most CPGs do not consider economic analysis for the implementation of their recommendations or that the cost implications are usually not fully described have been reported as some of the reasons for lower scores in the applicability domain [28, 33]. These results suggest that nowadays, most CPGs report their main objectives, the health questions, and the target population, but they have a lack guidance on their applicability; therefore, a major effort is required to address this issue, which reflects on factors such as implementation, organizational facilitators and barriers, additional materials provided, and economical implications. Similarly, it is important to disseminate the quality of available CPGs. This could improve clinicians’ adherence to CPGs, since it has been reported that healthcare professionals’ lack of adherence may be a result of distrust in CPG development processes and recommendations [34].

Regarding quality of CPGs and their recommendations, the following main recommendations were included in CPGs rated as “recommended” and including grading of evidence; thus, these may be key recommendations for clinical practice: (i) rapid access to clinics should be available for patients who have a suspicious lesion of oral cancer [17]; (ii) if the lesion has not resolved, clinicians should perform a biopsy of the lesion and/or refer the patient to a specialist [21]; (iii) a biopsy should be taken from the most suspicious part of the tumor and its report should be clearly described [20]; (iv) fine needle aspiration cytology should be used in the investigation of head and neck masses [17]; (v) every uncommon tumor diagnosis besides classical OSCC should be reviewed by an expert from a reference laboratory [20]; (vi) the autofluorescence, tissue reflectance, or vital staining adjuncts for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders are not recommended [21]; (vii) cytologic adjuncts are not recommended for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders, it should be an alternative if the patient declines a biopsy [21]; (viii) the use of commercially available salivary adjuncts for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders should only be considered in the context of research [21]; (ix) for adult patients with no clinically evident lesions or symptoms, no further action is necessary at that time [21]. This approach is based on the fact that high-quality CPGs are likely to provide helpful recommendations [33]. However, we wish to highlight that all these recommendations should be considered with caution because we only performed a descriptive analysis with no assessment of the quality of the evidence underlying each recommendation. For this purpose, it is necessary to use other tools such as the GRADE framework [35]. Moreover, most of these recommendations were based on low or very low level of evidence. Likewise, some CPGs did not take in account key risk factors to define their target population for oral cancer screening. It has been reported that oral cancer screening in general population is considered unnecessary, whereas that screening has a value in reducing the oral cancer mortality in high-risk group of population [36]. Therefore, any recommendations and practice points should be considered in the context of clinical judgment for each patient, his/her values and preferences, the available alternatives and their risk/benefit ratio, the available resources, and other contextual aspects [37].

Some CPGs developed by important healthcare organizations, such as the British Dental Association [38], the College of Dental Surgeons of British Columbia [39], Royal Australian College of General Practitioners [40], Australian Head and Neck Cancer Working Group [41], and individual authors as Kerawala [42], were excluded since they did not provide a written methods section. Therefore, we did not assess all existing recommendations on screening and diagnosis of oral cancer that may impact the clinical practice of healthcare professionals. However, a thorough review of the methodology used to develop a CPG is mandatory to evaluate its quality and the reliability of its recommendations [32].

We wish to highlight that the AGREE II instrument lacked clear instructions regarding the weight of the different domain scores when determining the optimal CPG [31, 43]. It did not set minimum domain scores or score patterns across different domains that would allow establishing a difference between high- and low-quality CPGs [8, 44]. These decisions are left to the user’s discretion [45]. Therefore, to improve the selection of optimal CPGs for clinical use, instead of assigning different weights across domains, we based on inter-appraiser agreement.

Among the main implications of our study is evidencing the need to improve CPG-development processes in this area, considering methodological aspects and applicability. The variability across the included CPGs shows the importance of identifying high-quality CPGs before implementing recommendations. For instance, the use of recommendations from low-quality CPGs may not meet effective health outcomes or might not contemplate the risk of their use in specific scenarios [28]. To standardize high-quality care, CPGs must be developed to minimize the use of unnecessary—and sometimes even harmful—medical interventions [44]. Therefore, it is essential to make available high-quality CPGs on screening and diagnosis of oral cancer that could serve as a useful and reliable tool for clinical decision-making. Authors have reported that CPGs must be based on the best available evidence and need to use validated recommendation-rating systems, to provide an explicit connection with the evidence [28].

This study has several strengths, such as the use of a protocol describing aims, selection criteria, planned methodology, and data analysis. The access to the included CPGs had no barrier, since they were available in full-text with no charges. Moreover, all information regarding the methodological quality of CPGs was obtained through a systematic search and was assessed independently by four appraisers using a standardized instrument. Currently, the AGREE II instrument is the only reliable and validated tool that allows a quantitative comparison of CPGs, providing also a methodological strategy for the development of CPGs, and the type of information that should be reported [7].

A limitation of this study might be our inability to retrieve CPGs that are not indexed or easily accessible. Nevertheless, some authors have reported that the methodology quality of non-indexed CPGs is likely lower than that of those indexed [6]. Likewise, the AGREE II tool was only used to evaluate the methods used to formulate and present recommendations, and not to appraise their validity; consequently, we only performed a description of recommendations. Another limitation is the restriction of CPGs in English, thus limiting the external validity of these findings to non-English CPGs. Likewise, although the English version of the German CPG [22] for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Oral Cavity Cancer was fully described, we were unable to read the full version in German. Hence, this CPG could possibly score higher in some domains.

Conclusion

The overall methodological quality of CPGs providing recommendations on screening and diagnosis of oral cancer is moderate, with only half of the included CPGs being assessed as recommended for clinical practice. The lowest domain scored was “applicability”. Most recommendations were based on a low or very low level of evidence. One of the most common recommendations across all CPGs is that clinicians should perform a biopsy of the lesion and/or refer the patient to a specialist for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders. Thus, it is essential that all CPGs provide a clear implementation strategy. This could facilitate clinicians’ adherence to CPGs, contributing to evidence-based health care.

References

Grilli R, Magrini N, Penna A, Mura G, Liberati A (2000) Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: the need for a critical appraisal. Lancet 355(9198):103–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02171-6

Chen YP, Wang YQ, Li WF, Chen L, Xu C, Lu TX, Lin AH, Yao JJ, Li YC, Sun Y, Mao YP, Ma J (2017) Critical evaluation of the quality and recommendations of clinical practice guidelines for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 15(3):336–344

Eslava-Schmalbach J, Sandoval-Vargas G, Mosquera P (2011) Incorporating equity into developing and implementing for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota) 13(2):339–351

Lee GH, McGrath C, Yiu CK (2016) Developing clinical practice guidelines for caries prevention and management for pre-school children through the ADAPTE process and Delphi consensus. Health Res Policy Syst 14(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0117-0

Graham ID, Beardall S, Carter AO, Glennie J, Hebert PC, Tetroe JM, McAlister FA, Visentin S, Anderson GM (2001) What is the quality of drug therapy clinical practice guidelines in Canada? CMAJ 165(2):157–163

Fuentes Padilla P, Martinez G, Vernooij RW, Cosp XB, Alonso-Coello P (2016) Nutrition in critically ill adults: a systematic quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines. Clin Nutr 35(6):1219–1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.03.005

Brouwers M, Kho M, Browman G, Burgers J, Cluzeau F, Feder G (2010) AGREE next steps consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 182(18):E839–E842. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090449

Brouwers M, Kho M, Browman G, Burgers J, Cluzeau F, Feder G (2010) For the AGREE next steps consortium. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ 182(10):E472–E478. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.091716

Warnakulasuriya S (2009) Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol 45(4–5):309–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2017) Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 67(1):7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21387

Moreira MA, Lessa LS, Bortoli FR, Lopes A, Xavier EP, Ceretta RA, Sonego FGF, Tomasi CD, Pires PDS, Ceretta LB, Perry IDS, Waleska Simoes P (2017) Meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging accuracy for diagnosis of oral cancer. PLoS One 12(5):e0177462. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177462

Costa K, Cunha K, Rodrigues F, Silva L, Dias E (2013) Concordance between cytopathology and incisional biopsy in the diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Braz Oral Res 27(2):122–127

Macey R, Walsh T, Brocklehurst P, Kerr AR, Liu JL, Lingen MW, Ogden GR, Warnakulasuriya S, Scully C (2015) Diagnostic tests for oral cancer and potentially malignant disorders in patients presenting with clinically evident lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5:CD010276. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010276.pub2

Madera Anaya MV, Franco JV, Merchan-Galvis AM, Gallardo CR, Bonfill Cosp X (2018) Quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines on treatments for oral cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 65:47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.03.001

AGREE (2009) (Update: 2013) The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation. AGREE. Ontario, Canada:The AGREE Next Steps Consortium. (http://www.agreetrust.org)

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174

SIGN (2006) SIGN (2006) The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Diagnosis and management of head and neck cancer. A national clinical guideline: 1–96. https://www.uhb.nhs.uk/Downloads/pdf/CancerPbDiagnosisHeadAndNeckCancer.pdf. Accessed 28 Jan 2018

Moyer VA, Force USPST (2014) Screening for oral cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 160(1):55–60. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-2568

AHS (2014) Alberta Health Services. Oral cavity cancer. Clinical Practice Guideline HN-002. Version 1: 1–22. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/cancer/if-hp-cancer-guide-hn002-oral-cavity.pdf. Accessed 28 Jan 2018

Grégoire V, Leroy R, Heus P, Van de Wetering F, Hooft L, Scholten R, Verleye L, Carp L, Clement P, Deron P, Goffin K, Hamoir M, Hauben E, Hendrickx K, Hermans R, Kunz S, Lenssen O, Nuyts S, Van Laer C, Vermorken J, Appermont E, De Prins A, Hebbelinck E, Hommez G, Vandenbruaene C, Vanhalewyck E, Vlayen J (2014) Oral cavity cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Good Clinical Practice (GCP). Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), Brussels KCE Reports 227

Lingen MW, Abt E, Agrawal N, Chaturvedi AK, Cohen E, D'Souza G, Gurenlian J, Kalmar JR, Kerr AR, Lambert PM, Patton LL, Sollecito TP, Truelove E, Tampi MP, Urquhart O, Banfield L, Carrasco-Labra A (2017) Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders in the oral cavity: a report of the American dental association. J Am Dent Assoc 148(10):712–727 e710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2017.07.032

Wolff KD, Follmann M, Nast A (2012) The diagnosis and treatment of oral cavity cancer. Dtsch Arztebl Int 109(48):829–835. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2012.0829

NICE (2015) NICE Guideline. In: Suspected Cancer: Recognition and Referral. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines, London, pp 1–378

NZGG (2009) New Zealand Guidelines Group. Suspected Cancer in primary care. Guidelines for investigation, referral and reducing ethnic disparities. Wellington: 1–190. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/suspected-cancer-guideline-sep09.pdf. Accessed 28 Jan 2018

Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, Morton SC, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Woolf SH (2001) Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated? Jama 286(12):1461–1467

Yaman ME, Gudeloglu A, Senturk S, Yaman ND, Tolunay T, Ozturk Y, Arslan AK (2015) A critical appraisal of the North American Spine Society guidelines with the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II instrument. Spine J 15(4):777–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2015.01.012

Jiang Y, Zhu XD, Qu S, Li L, Zhou Z (2015) Guidelines for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a systematic assessment of quality. Ear Nose Throat J 94(4–5):E14–E24

Seiffert A, Zaror C, Atala-Acevedo C, Ormeno A, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Alonso-Coello P (2018) Dental caries prevention in children and adolescents: a systematic quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines. Clin Oral Investig. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2405-2

Mubeen S, Patel K, Cunningham Z, O'Rourke N, Pandis N, Cobourne MT, Seehra J (2017) Assessing the quality of dental clinical practice guidelines. J Dent 67:102–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2017.10.003

Acuna-Izcaray A, Sanchez-Angarita E, Plaza V, Rodrigo G, de Oca MM, Gich I, Bonfill X, Alonso-Coello P (2013) Quality assessment of asthma clinical practice guidelines: a systematic appraisal. Chest 144(2):390–397. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-2005

Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Sola I, Gich I, Delgado-Noguera M, Rigau D, Tort S, Bonfill X, Burgers J, Schunemann H (2010) The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care 19(6):e58. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2010.042077

Erickson J, Sadeghirad B, Lytvyn L, Slavin J, Johnston BC (2017) The scientific basis of guideline recommendations on sugar intake: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 166(4):257–267. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2020

Wang Y, Ye ZK, Li JF, Cui XL, Liu LH (2018) Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a critical appraisal of clinical practice guidelines with the AGREE II instrument. Thromb Res 166:10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2018.03.017

Sox HC (2014) Assessing the trustworthiness of the guideline for management of high blood pressure in adults. Jama 311(5):472–474. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.284429

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ (2008) GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336(7650):924–926. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

Iyer S, Thankappan K, Balasubramanian D (2016) Early detection of oral cancers: current status and future prospects. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 24(2):110–114. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0000000000000237

Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD (2016) GRADE evidence to decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: introduction. BMJ 353:i2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2016

BDA (2010) Early detection and prevention of oral cancer: a management strategy for dental practice. The British Dental Association-Occasional paper, pp 1–37

CDSBC (2008) College of Dental Surgeons of British Columbia. Guideline for the early detection of Oral Cancer in British Columbia 2008: 1–8. https://www.cdsbc.org/CDSBCPublicLibrary/Oral-Cancer-Clinical-Practice-Guideline.pdf. Accessed 28 Jan 2018

RACGP (2012) The Royal Australian College of General Practitioner. Early detection of cancers. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice ('the red book') 8th edition: 68. https://www.racgp.org.au. Accessed 28 Jan 2018

AHNCWG (2013) Australian Head and Neck Cancer Working Group. South Australian Head and Neck Cancer Pathway: Optimising outcomes for all South Australians diagnosed: 1–146. http://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au. Accessed 28 Jan 2018

Kerawala C, Roques T, Jeannon JP, Bisase B (2016) Oral cavity and lip cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol 130(S2):S83–S89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215116000499

Vlayen J, Aertgeerts B, Hannes K, Sermeus W, Ramaekers D (2005) A systematic review of appraisal tools for clinical practice guidelines: multiple similarities and one common deficit. Int J Qual Health Care 17(3):235–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzi027

Jiang M, Liao LY, Liu XQ, He WQ, Guan WJ, Chen H, Li YM (2015) Quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines for respiratory diseases in China: a systematic appraisal. Chest 148(3):759–766. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-3201

Lytras T, Bonovas S, Chronis C, Konstantinidis AK, Kopsachilis F, Papamichail DP, Dounias G (2014) Occupational asthma guidelines: a systematic quality appraisal using the AGREE II instrument. Occup Environ Med 71(2):81–86. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2013-101656

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Ángela Merchán and Carmen Gallardo for participating in the guidelines assessment process, and to Andrea Cervera for proofreading this manuscript.

Funding

The Bolívar Gana con Ciencia grant financially supported Meisser Madera. This author is a Ph.D candidate at the Methodology and Biomedical Research and Public Health program, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Madera, M., Franco, J., Solà, I. et al. Screening and diagnosis of oral cancer: a critical quality appraisal of clinical guidelines. Clin Oral Invest 23, 2215–2226 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2668-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2668-7