Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the quality of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for dental caries prevention in children and adolescents

Materials and methods

We performed a systematic search of CPGs on caries preventive measures between 2005 and 2016. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, TripDatabase, websites of CPG developers, compilers of CPGs, scientific societies and ministries of health. We included CPGs with recommendations on sealants, fluorides and oral hygiene. Three reviewers independently assessed the included CPGs using the AGREE II instrument. We calculated the standardised scores for the six domains and made a final recommendation about each CPG. Also, we calculated the overall agreement among calibrated reviewers with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Results

Twenty-two CPGs published were selected from a total of 637 references. Thirteen were in English and nine in Spanish. The overall agreement between reviewers was very good (ICC = 0.90; 95%CI 0.89–0.92). The mean score for each domain was the following: Scope and purpose 89.6 ± 12%; Stakeholder involvement 55.0 ± 15.6%; Rigour of development 64.9 ± 21.2%; Clarity of presentation 84.8 ± 14.1%; Applicability 30.6 ± 31.5% and Editorial independence 59.3 ± 25.5%. Thirteen CPGs (59.1%) were assessed as “recommended”, eight (36.4%) “recommended with modifications” and one (4.5%) “not recommended”.

Conclusions

The overall quality of CPGs in caries prevention was moderate. The domains with greater deficiencies were Applicability, Stakeholder involvement and Editorial independence.

Clinical relevance

Clinicians should use the best available CPGs in dental caries prevention to provide optimal oral health care to patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dental caries is a common preventable disease and is still a major oral health problem around the world, affecting up to 90% of children and adolescents [1,2,3]. Caries can be arrested in early stages but, without proper prevention, the disease can progress until destruction or tooth loss, affecting the quality of life of the child, with potential negative social and economic repercussions in the family [4, 5]. Periodical dental control, oral hygiene, antimicrobial agents, fluorides, low-carbohydrate diet and dental sealants are preventive measures that can help prevent irreversible problems on the teeth such as dental caries [6].

Many countries have implemented preventive programs to decrease the incidence of caries in the general population. To standardise the dental caries preventive measures, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) have been developed, facilitating clinician and patient decisions about the most appropriate health care [7]. These are instruments that provide specific recommendations to optimise results, minimise risks and promote a cost-effective practice for health care professionals [8,9,10,11]. CPG recommendations should be based on the best available scientific evidence to obtain the desirable outcomes in patient care [12].

There are multiple CPGs for dental caries prevention, primarily developed by governmental health institutions and dental societies. Some countries adopt and/or adapt existing CPGs to their settings, leading to a vast variability in the CPG quality. The quality assessment of guidelines in other medical specialties has demonstrated high variability and is rarely considered optimal [12,13,14].

We found only one study that assessed the quality of CPGs in the prevention of dental caries; however, it was limited to European guidelines about fissure sealants [13]. The authors concluded that, according to the AGREE II instrument, the three guidelines evaluated showed high variability in the quality. Therefore, we conducted a systematic assessment of the quality of the CPGs about dental caries prevention in children and adolescents.

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted a systematic assessment of the quality of CPGs for dental caries prevention in children and adolescents with the AGREE II instrument.

Search strategy and selection of CPGs

We performed a systematic search of scientific literature published between 2005 and 2016 to identify CPGs about caries preventive measures. The search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS and Trip databases. It was complemented by hand searching websites of guideline developers (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE)), CPG compilers (National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC) and Guidelines International Network (GIN)), scientific societies of paediatric dentistry and Ministries of Health (Online Resource 1).

We included dental CPGs in English and Spanish that included at least one recommendation related to caries prevention measures (fluoride, sealants, oral hygiene and oral health counselling) and carried out a systematic search of the literature. We excluded CPGs developed exclusively for the adult population or patients with special care needs, previous versions of the same guideline, letters to the editor, policies and conference summaries. Two reviewers (A.S. and C.A.A.) independently evaluated the search results to determine eligibility of the references. In case of differences between the reviewers, consensus was reached by discussion or in consultation with a third reviewer (C.Z.).

Quality assessment

A pilot test in five potentially eligible CPGs was performed to calibrate the reviewers. As a minimum, information that involves subjective interpretation and information that is critical to the interpretation of results should be extracted independently by at least two reviewers [15]. This is also what AGREE II recommends to increase the reliability of the assessment [16, 17]. Three calibrated reviewers (A.S., C.A.A., C.Z. or A.O.) independently evaluated the CPGs using the online AGREE tool website My AGREE PLUS [17]: two paediatric dentists and two experts in research methodology. The AGREE II instrument includes 23 items divided into six domains: (1) Scope and purpose, refers to the aim of the guidelines; (2) Stakeholder involvement, represents the views of the intended users; (3) Rigour of development, reflects the quality of the CPG elaboration process and its recommendations; (4) Clarity of presentation, is about the structure of the guidelines; (5) Applicability, shows the barriers and facilitators for the implementation of the CPG, considering also the financial implications to implement the recommendations; and (6) Editorial independence, illustrates the transparency in the formulation of the guidelines recommendations. Each of the 23 items is rated from 1 to 7 points in the Likert scale [16].

Data analysis

We calculated the domain scores by summing up all scores of the individual items included in a domain and by scaling the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain [16]. If discrepancies were more than 3 points, or if the standard deviation (SD) in an item was greater than or equal to 1.5 SD, the item of the guideline was reassessed by the reviewers and agreement was reached [18]. The guidelines were examined separately according to their scope: fluorides, pit and fissure sealants, oral hygiene or CPGs that considered more than one preventive measure.

Inter-rater reliability

We calculated the intraclass coefficient (ICC) with its 95% confidence interval (95%CI) as an indicator of overall agreement between reviewers for each of the 23 items of the AGREE II instrument. According to the scale proposed by Landis and Koch, the degree of agreement between 0.01 and 0.20 is slight, from 0.21 to 0.40 is fair, from 0.41 to 0.60 is moderate, from 0.61 to 0.80 is substantial and from 0.81 to 1.00 is very good [19]. We used the statistical package IBM SPSS (version 23.0).

Identifying high-quality CPGs

The reviewers considered the “overall quality” of the CPGs and made a final recommendation about each guideline (“recommended”, “recommended with modifications” or “not recommended”) [16]. They also classified the CPG as high quality when at least three of the domains showed a score of 60% or higher, including the Rigour of development domain [18, 20, 21].

Results

Literature search

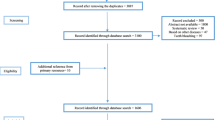

Of the 878 citations systematically searched, duplicates were firstly eliminated, leaving 637 citations for title and abstract review. Five hundred fifty-six titles and 56 abstracts were excluded because they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. Of the 25 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, 3 were excluded because they did not declare a systematic search of evidence [22,23,24,25]. Characteristics of the excluded studies can be found in the Online Resource 2. Finally, 22 CPGs were included (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the included CPGs

The characteristics of the CPGs are listed in Table 1. Thirteen of the included CPGs were in English: seven from the USA [26,27,28,29,30,31,32], three from Ireland [33,34,35], one from Scotland [36], one from Malaysia [37] and one from New Zealand [38]. The other nine were in Spanish: three from Chile [39,40,41], two from Colombia [42, 43], two from Mexico [44, 45], one from Ecuador [46] and one from Spain [47].

One CPG was exclusively about infants, one only considered preschool children and one was about caries in adolescents. Nine CPGs included infants, children and adolescents and eight guidelines aimed for the general population, including children and/or adolescents. Nineteen CPGs included recommendations about fluorides, but only five of them were exclusive to this topic. The fluoride preventive measure recommendations included varnish, toothpaste, foam, mouth rinse, gel and dietary supplements.

Thirteen CPGs formulated recommendations about pit and fissure sealant, but only three were exclusive about this topic. Other preventive measures considered in the recommendations of the guidelines with more than one preventive measure were diet, oral hygiene, oral health education, chlorhexidine varnish and mouth rinse, periodical dental examinations, casein phosphopeptide and xylitol chewing gum. We found only one guideline exclusive to oral hygiene, and there were no CPGs limited to oral health counselling only. For analysis, the CPG of oral hygiene was assessed in the group of guidelines with more than one preventive measure.

Of the 22 guidelines, 15 declared an instrument to assess the quality of the included studies to develop the recommendations: Three used the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) checklist, two used the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) system, two used the AGREE instrument to assess the quality of other CPGs and eight used more than one system. The level of evidence and the grade of recommendation used were declared in 18 of the guidelines.

Appraisal of CPGs

The final standardised scores by domain, CPG and preventive measure, in addition to the overall recommendation, are presented in Tables 2, 3 and 4. Figure 2 shows the mean scores for all preventive measures separated by domains. The overall agreement between the three reviewers for the CPG evaluation with the AGREE II instrument was very good (ICC = 0.90; 95%CI 0.89–0.92).

Scope and purpose

The mean score for this domain was 89.5 ± 12.3% (range 76–100%) in the sealant CPGs, 96.7 ± 3% (range 93–100%) in the fluoride CPGs and 87.1 ± 13.5% (range 54–100%) in the CPGs with more than one preventive measure. The mean score of all the 22 guidelines was 89.6 ± 12% (range 54–100%). Only one (4.5%) guideline scored below 60% in this domain [31].

Stakeholder involvement

For this domain, the main score for the sealant guidelines was 59.3 ± 3.7% (range 56–63%), for the fluoride guidelines was 57.8 ± 12.9% (range 37–72%) and for the CPGs with more than one preventive measure was 53 ± 18.1% (range 11–91%). The global mean score was 55 ± 15.6% (range 11–91%). Seven CPGs (31.8%) scored above 60% in this domain [32,33,34,35,36, 38, 41].

Rigour of development

The mean score for this domain was 73.8 ± 19.6% (range 53–92%) in the sealant CPGs, 76.5 ± 21.2% (range 39–90%) in the fluoride guidelines and 58.9 ± 20.4% (range 29–90%) in the CPGs with more than one preventive measure. The global mean score was 64.9 ± 21.2% (range 29–92%). Nine of the included guidelines (40.9%) scored below 60% [27, 30, 31, 39, 43,44,45,46,47].

Clarity of presentation

The mean score for this domain was 93.8 ± 5.3% (range 91–100%) in the sealant CPGs, 91.5 ± 7.9% (range 78–98%) in the fluoride guidelines and 80.4 ± 15.5% (range 50–100%) in the CPGs with more than one preventive measure. The global mean score was 84.8 ± 14.1% (range 50–100%). Only two guidelines (9.1%) scored below 60% in this domain [30, 31].

Applicability

The mean score for this domain was 29.2 ± 41% (range 3–76%) in the sealant CPGs, 26.7 ± 34% (range 0–86%) in the fluoride guidelines and 32.3 ± 31.4% (range 0–93%) in the CPGs with more than one preventive measure. The global mean score was 30.6 ± 31.5% (range 0–93%). Four of the assessed CPGs (18.2%) scored above 60% in this domain [33,34,35,36], and two guidelines (9.1%) scored 0% [27, 30].

Editorial independence

The mean score for this domain was 50.9 ± 22.5% (range 25–64%) in the sealant CPGs, 57.2 ± 33.4% (range 6–92%) in the fluoride guidelines and (61.9 ± 24.6% (range 11–86%) in the CPGs with more than one preventive measure. The global mean score was (59.3 ± 25.5% (range 6–92%). Nine of the elected guidelines (40.1%) scored below 60% [26,27,28, 30, 31, 38, 39, 41, 45].

Overall assessment

Thirteen of the 22 assessed CPGs (59.1%) were “recommended” by the reviewers (2 of sealants [26, 35], 4 of fluorides [28, 29, 33, 38] and 7 of the CPGs with more than one preventive measure [32, 34, 36, 37, 40,41,42]); eight (36.4%) were “recommended with modifications (1 of sealants [44], 1 of fluorides [27] and 6 of the CPGs with more than one preventive measure [30, 39, 43, 45,46,47]); and one (4.5%) was “not recommended” [31]. The same 13 CPGs evaluated as “recommended” were classified as high quality, scoring ≥ 60% in at least three domains, including the Rigour of development domain. The one “not recommended” guideline scored below 60% in all the domains.

Discussion

The evaluation of 22 worldwide CPGs in dental caries prevention in children and adolescent patients showed a moderate quality. Thirteen were classified as “recommended” and as high quality. However, only 4 CPGs scored above 60% in all six domains (1 published by the SIGN and 3 by the Irish Oral Health Services Guideline Initiative).

The guideline of the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) on adolescent oral health care [31] was the only one evaluated as “not recommended”. The main difference between this guideline and the other three AAPD guidelines, classified as “recommended with modifications”, was in the Scope and purpose domain because it did not have a clear objective.

Of all the guidelines included, the domain with the highest overall score was Scope and purpose (90%), followed by Clarity of presentation (85%) and Rigour of development (65%). In the other three domains, the overall score was below 60%, with the Applicability domain being the lowest (15%).

The CPGs considered in our study showed an overall higher quality than the ones assessed in other topics, with a 59.1% of “recommended” guidelines compared to a 37% reported in the literature [48]. Studies assessing the quality of CPGs are practically new in dentistry and have been reported since 2015 in the areas of dental radiology, implants, orthodontics and preventive dentistry [13, 49,50,51,52]. The guideline assessment of these studies in dentistry also obtained the highest scores in the Scope and purpose and Clarity of presentation domains, with the Applicability domain being the worst [49,50,51,52].

The Scope and purpose domain was the best assessed, which shows the overall aim of the guideline. The guidelines with the lower scores in this domain failed in giving a detailed description of the health questions covered by the CPG. The aim of the CPG needs to be clear and in coherence with the key recommendations to guide the user in implementing the most favourable care for a specific health problem [17].

Analysing the Stakeholder involvement domain, it appears that user opinions and preferences were not considered, or the results were simply not reported. Additionally, most guidelines did not include or report the specialist or expert involved in their development. The evidence shows that guidelines improve when specialists, experts and patients participate effectively in the process, thereby keeping it transparent, helping to define the objectives and showing that the recommendations are not based on bias decisions [53, 54].

The Rigour of development domain is usually considered the main domain in the assessment of the clinical guidelines. It directly evaluates the gathering of information and the quality of the development process of the recommendations. In our assessment, this domain obtained a high score, except in nine of the CPGs that scored below 60% in this domain. The main problems in our assessment were not indicating the limitations of the evidence, not reporting the possible harmful effects and not specifying the results of the expert’s external review, and their implications in the development process. It seems easier to highlight the positive aspects of preventive measures; nonetheless, every procedure has risks that need to be declared. For instance, fluorides can produce fluorosis; a defective sealant can put the teeth at further risk of caries than possibly not sealing them at all [55,56,57]. The guidelines need to be clear on this point, so that users and patients can make informed decisions about their dental health. On the other hand, the importance of the results of the external review is significant, as some guideline development groups can show bias in the development of their own guidelines [58, 59].

The Clarity of presentation domain was the second best evaluated, where the main problems in some of the CPGs were the ambiguity and the format in the presentation of the recommendations, which is important to make the guideline easier to use [16].

The low scores in the Applicability domain are mostly because the assessed CPGs did not consider economic analysis for the implementation of the recommendation guidelines. The evidence shows that economic analysis is seldom incorporated in the development of CPGs [60]. Further economic evaluations in preventive measures in dentistry are needed and should be incorporated in the guidelines [61, 62]. The economic analysis in the guidelines can impact both the quality of care and the efficient allocation of resources. Studies in medicine assessing cost-effectiveness of the guidelines have shown that there was an increment of QALYs using the evidence-based recommendations of the guidelines [8,9,10, 63].

There is also a lack of information as to how the guidelines are going to be disseminated and implemented. These measures should be available to patients, clinicians and the general population. However, there is no reliable evidence on which implementation method is the best [64].

The problem presented in the Editorial independence domain was in the declaration of the conflicts of interest, although, this was included in almost all the guidelines, it only considered financial conflicts of interest. For instance, political, intellectual or social conflicts of interest were not declared. Guideline members should make the interests of the target population their sole concern and set aside any competing financial or professional interests. It is particularly important that the funding body and the group members of the CPGs state their conflicts interest, because CPGs are being used in decisions regarding insurance coverage and standards of care [58]. The best way to avoid the influence of external interests is to link the recommendations to the evidence, particularly systematic reviews and avoiding those panellists with conflicts in the decision-making process [59, 65].

There is only one study in dentistry that focused on dental caries prevention and assessed European pit and fissure sealant CPGs [13]. In view of the differences in the inclusion criteria, it was difficult to compare our work with the above study; nonetheless, in both studies, the best results were in the Scope and purpose domain. They analysed three guidelines; the Irish CPG was the only one coinciding with our evaluation [35]. The scores of the Irish guideline are very similar between both studies; the main difference is that we classified this guideline as “recommended” and the European study as “recommended with modifications”.

We found a lack of uniformity in the grading systems used in the CPGs, and four of them did not rate the quality of the evidence and strength of their recommendations (three from the AAPD and one from the New Zealand Guidelines Group). Clinical guidelines must be based on the best available evidence and need to use validated recommendation rating systems, to provide an explicit connection with the evidence. It helps to avoid bias in the recommendation development process with the goal of developing high-quality guidelines [59].

Strengths and limitations

We identified some limitations in our review process. First, the study did not include all preventive measures in dental caries, such as diet assessment or chemical agents (for example xylitol and chlorhexidine). We decided to include the measures directly related to dental caries prevention and those that are usually used in public health measures. And second, we only considered guidelines in Spanish and English language, which prompted the omission of CPGs.

Access to the CPGs was not an obstacle in this study. The CPGs were all available in open access and free of charge, allowing easy dissemination of the information. The search of the methodological/procedure and manuals of the guidelines was sometimes difficult, particularly in guidelines that were developed with older versions of an updated manual. The data analysis was much easier in those guidelines that specified where to locate these manuals, or those that included a clear and complete methodology.

The main strengths of this study are that information regarding development process of CPGs was obtained in a systematic search of the literature and was evaluated independently by three calibrated reviewers using a standardised tool. The AGREE II instrument is currently the only validated and reliable instrument that enables a quantitative comparison of CPGs, and is designed to help users to evaluate their methodological quality. This tool also provides a methodological strategy for the development of guidelines and informs about the type of information to be reported [16].

To our knowledge, we are the first to report the quality assessment of dental guidelines in Spanish. These will be useful in Spanish-speaking countries, with private and public health services and dental societies able to readily access the “recommended” guidelines in the development and adaptation of their own guidelines. Access to this information is especially important in Latin American countries where the prevalence of dental caries continues to be a public health problem [4]. We carried out an extensive systematic search of scientific evidence, and three calibrated evaluators did the assessment of the CPGs, resulting in a high level of concordance between them. Finally, our team included clinical experts and methodologists with vast experience in CPGs.

Implications for practice and research

The variability of the guidelines stresses the importance of the clinicians’ need to identify high-quality guidelines before implementing the recommendations. A low-quality CPG may not meet effective health results in the use of its recommendations or might not consider the risks or disadvantages of using those recommendations in a specific scenario. Eight of the guidelines were “recommended with modifications”, which hopefully will prompt a discussion in the CPG development process to improve future updates.

Improvements in the quality can be made by using a standardised framework to present the recommendations and by including patient preferences in the development process and also by incorporating economic evaluations and cost-effectiveness studies of the measures, as well as through evaluations of the quality of the evidence available. Our results facilitate the decision-making process in the selection of the most suitable CPG in dental caries prevention.

Conclusion

CPGs in dental caries prevention in children and adolescents during the last 10 years showed a high quality in the assessment with the AGREE II instrument. However, they presented some deficiencies, in the domains of Stakeholder involvement, Applicability and Editorial independence.

References

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2016) Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_ECCClassifications1.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2017

Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C (2005) The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ 83:661–669

Zaror C, Pineda P, Orellana J (2011) Prevalence of early childhood caries and associated factors in 2 and 4 year-old Chilean children. Int J Odontostomatol 5:171–177

Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB (2007) Dental caries. Lancet 369(9555):51–59

Çolak H, Dülgergil ÇT, Dalli M, Hamidi MM (2013) Early childhood caries update: a review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. J Nat Sci Biol Med 4:29–38

Fejerskov O, Nyvad B, Kidd E (2015) Dental caries: the disease and its clinical management. Wiley Blackwell, Oxford

Field MJ, Lohr KN (1992) Guidelines for clinical practice: from development to use. National Academies Press, Washington

McEwan P, Gordon J, Evans M, Ward T, Bennett H, Bergenheim K (2015) Estimating cost-effectiveness in type 2 diabetes: the impact of treatment guidelines and therapy duration. Med Decis Mak 35:660–670

Moran AE, Odden MC, Thanataveerat A, Tzong KY, Rasmussen PW, Guzman D, Williams L, Bibbins-Domingo K, Coxson PG, Goldman L (2015) Cost-effectiveness of hypertension therapy according to 2014 guidelines. N Engl J Med 372:447–455

Deaño RC, Pandya A, Jones EC, Borden WB (2014) A look at statin cost-effectiveness in view of the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol management guidelines. Curr Atheroscler Rep 16:1–7

Giannattasio A, Poggi E, Migliorati M, Mondani P, Piccardo I, Carta P, Tomarchio N, Alberti G (2015) The efficacy of Italian guidelines in promoting oral health in children and adolescents. Eur J Paediatr Dent 16:93–98

Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Solà I, Gich I, Delgado-Noguera M, Rigau D, Tort S, Bonfill X, Burgers J, Schunemann H (2010) The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care 19:e58. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2010.042077

San Martin-Galindo L, Rodríguez-Lozano F, Abalos-Labruzzi C, Niederman R (2017) European fissure sealant guidelines: assessment using AGREE II. Int J Dent Hyg 15(1):37–45

Chen YP, Wang YQ, Li WF, Chen L, Xu C, Lu T-X, Lin A-H, Yao JJ, Li YC, Sun Y (2017) Critical evaluation of the quality and recommendations of clinical practice guidelines for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 15:336–344

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors) (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.handbook.cochrane.org

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L (2010) AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 182:e839–e842

AGREE (2009) The appraisal of guidelines for research & evaluation. The AGREE Next Steps Consortium. http://www.agreetrust.org/agree-ii/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Fuentes Padilla P, Martínez G, Vernooij RW, Cosp XB, Alonso-Coello P (2016) Nutrition in critically ill adults: a systematic quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines. Clin Nutr 35:1219–1225

Prieto L, Lamarca R, Casado A (1998) La evaluación de la fiabilidad en las observaciones clínicas: el coeficiente de correlación intraclase. Med Clin 110:142–145

Yaman ME, Gudeloglu A, Senturk S, Yaman ND, Tolunay T, Ozturk Y, Arslan AK (2015) A critical appraisal of the North American spine society guidelines with the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II instrument. Spine J 15:777–781

Brosseau L, Rahman P, Poitras S, Toupin-April K, Paterson G, Smith C, King J, Casimiro L, De Angelis G, Loew L (2014) A systematic critical appraisal of non-pharmacological management of rheumatoid arthritis with appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II. PLoS One 9:e95369

New South Wales Ministry of Health (2014) Early childhood oral health guidelines for child health professionals. www.health.nsw.gov.au. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Chandna P, Adlakha VK (2010) Oral health in children guidelines for pediatricians. Indian Pediatr 47:323–327

New South Wales Ministry of Health (2013) Pit and fissure sealants: use of in oral health services NSW. www.health.nsw.gov.au. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (2010) Prevention and management of dental caries in children. http://www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/caries-in-children/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Beauchamp J, Caufield PW, Crall JJ, Donly K, Feigal R, Gooch B, Ismail A, Kohn W, Siegal M, Simonsen R (2008) Evidence-based clinical recommendations for the use of pit-and-fissure sealants: a report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc 139:257–268

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2014) Guideline on fluoride therapy. Pediatr Dent. http://www.aapd.org/policies/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Rozier RG, Adair S, Graham F, Iafolla T, Kingman A, Kohn W, Krol D, Levy S, Pollick H, Whitford G (2010) Evidence-based clinical recommendations on the prescription of dietary fluoride supplements for caries prevention: a report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc 141:1480–1489

Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT, Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Donly KJ, Frese WA, Hujoel PP, Iafolla T, Kohn W, Kumar J (2013) Topical fluoride for caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc 144:1279–1291

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2014) Guideline on infant oral health care. Pediatr Dent. http://www.aapd.org/policies/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2015) Guideline on adolescent oral health care. Pediatr Dent. http://www.aapd.org/policies/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Moyer VA, Preventive Services Task Force US (2014) Prevention of dental caries in children from birth through age 5 years: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Pediatrics 133:1102–1111

Irish Oral Health Services Guideline Initiative (2008) Topical fluorides: evidence-based guidance on the use of topical fluorides for caries prevention in children and adolescents in Ireland. https://www.ucc.ie/en/ohsrc/publications-guidelines/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Irish Oral Health Services Guideline Initiative (2009) Strategies to prevent dental caries in children and adolescents: evidence-based guidance on identifying high caries risk children and developing preventive strategies for high caries risk children in Ireland. https://www.ucc.ie/en/ohsrc/publications-guidelines/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Irish Oral Health Services Guideline Initiative (2010) Pit and fissure sealants: evidence-based guidance on the use of sealants for the prevention and management of pit and fissure caries. https://www.ucc.ie/en/ohsrc/publications-guidelines/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2014) Dental interventions to prevent caries in children (SIGN publication no. 138). http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/index.html. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Ministry of Health (2012) Clinical practice guidelines: management of severe early childhood caries. http://www.moh.gov.my/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

New Zealand Guidelines Group (2009) Guidelines for the use of fluorides. http://www.health.govt.nz/publications. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Ministerio de Salud (2009) Guía clínica: atención primaria odontológica del preescolar de 2 a 5 años. http://web.minsal.cl/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Ministerio de Salud (2013) Guía clínica: salud oral en adolescentes de 10 a 19 años: prevención, diagnóstico y tratamiento de caries. http://web.minsal.cl/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Ministerio de Salud (2013) Guía Clínica Salud Oral integral para niños y niñas de 6 años. http://web.minsal.cl/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Secretaría Distrital de Salud, Colombia (2010) Guía de práctica clínica en salud oral: higiene oral. http://www.saludcapital.gov.co/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Secretaría Distrital de Salud (2010) Guía de práctica Clínica en Salud Oral: Infancia y Adolescencia. http://www.saludcapital.gov.co/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Secretaría de Salud (2011) Guía de práctica clínica: Prevención de caries Dental a través de la Aplicación de Selladores de Fosetas y Fisuras Dentales. http://cenetec-difusion.com/gpc-sns/?cat=141. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Secretaría de Salud (2012) Guía de práctica clínica: prevención y diagnóstico de la caries Dental en pacientes de 6 a 16 años de edad. http://cenetec-difusion.com/gpc-sns/?cat=141. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Ministerio de Salud Pública (2015) Caries, guía de práctica clínica. http://salud.gob.ec/. Accessed 01 Aug 2016

Casals Peidró E, García Pereiro M (2014) Guía de práctica clínica para la prevención y tratamiento no invasivo de la caries dental. RCOE 19:189–248

Armstrong JJ, Goldfarb AM, MacDermid JC (2017) Improvement evident but still necessary in clinical practice guideline quality: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 81:13–21

Faggion CM Jr, Apaza K, Ariza-Fritas T, Málaga L, Giannakopoulos NN, Alarcón MA (2017) Methodological quality of consensus guidelines in implant dentistry. PLoS One 12:e0170262. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173437

Goodwin T, Devlin H, Glenny A, O'Malley L, Horner K (2017) Guidelines on the timing and frequency of bitewing radiography: a systematic review. Br Dent J 222:519–526. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.314

Horner K, O'Malley L, Taylor K, Glenny A (2014) Guidelines for clinical use of CBCT: a review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 44:20140225. https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20140225

Tejani T, Mubeen S, Seehra J, Cobourne MT (2017) An exploratory quality assessment of orthodontic clinical guidelines using the AGREE II instrument. Eur J Orthod 39:654–659. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjx017

Roman BR, Feingold J (2014) Patient-centered guideline development best practices can improve the quality and impact of guidelines. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 151(4):530–532

Armstrong MJ, Mullins CD, Gronseth GS, Gagliardi AR (2017) Recommendations for patient engagement in guideline development panels: a qualitative focus group study of guideline-naïve patients. PLoS One 12:e0174329. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174329

Alves LS, Giongo FCMS, Mua B, Martins VB, Barbachan E Silva B, Qvist V, Maltz M (2017) A randomized clinical trial on the sealing of occlusal carious lesions: 3–4-year results. Braz Oral Res e44:31. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0044

Condò R, Cioffi A, Riccio A, Totino M, Condò S, Cerroni L (2013) Sealants in dentistry: a systematic review of the literature. Oral Implantol (Rome) 6:67–74

Yeung CA (2008) A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation. Evid Based Dent 9:39–43

Sox HC (2017) Conflict of interest in practice guidelines panels. JAMA 317:1739–1740

IOM (Institute of Medicine) (2011) Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209539/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK209539.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2017

Wallace JF, Weingarten SR, Chiou CF, Henning JM, Hohlbauch AA, Richards MS, Herzog NS, Lewensztain LS, Ofman JJ (2002) The limited incorporation of economic analyses in clinical practice guidelines. J Gen Intern Med 17:210–220

Källestål C, Norlund A, Söder B, Nordenram G, Dahlgren H, Petersson LG, Lagerlöf F, Axelsson S, LingstroÈm P, Mejàre I (2003) Economic evaluation of dental caries prevention: a systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand 61:341–346

Leo M, Cerroni L, Pasquantonio G, Condò S, Condò R (2016) Economic evaluation of dental sealants: a systematic review. Clin Ter 167:e13–e20. https://doi.org/10.7417/T.2016.1914

Zhang S, Incardona B, Qazi SA, Stenberg K, Campbell H, Nair H, Group SAW (2017) Cost-effectiveness analysis of revised WHO guidelines for management of childhood pneumonia in 74 countdown countries. J Glob Health 7:010409. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.07.010409

Grimshaw J, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay C, Vale L, Whitty P, Eccles M, Matowe L, Shirran L (2005) Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 21:149–149

Norris SL, Holmer HK, Ogden LA, Burda BU (2011) Conflict of interest in clinical practice guideline development: a systematic review. PLoS One 6:e25153. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025153

Acknowledgements

Andrea Seiffert is a MSc candidate, Faculty of Dentistry, Universidad de La Frontera, Temuco, Chile. Ma. José Martínez is funded by a Miguel Servet research contract from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and European Social Fund (CP15/00116). We would like to acknowledge Ingrid Obrecht for her help in the English editing process.

Funding

This project was partially funded by a grant from Universidad de La Frontera, DIUFRO No. DI16-0087.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seiffert, A., Zaror, C., Atala-Acevedo, C. et al. Dental caries prevention in children and adolescents: a systematic quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines. Clin Oral Invest 22, 3129–3141 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2405-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2405-2