Abstract

Purpose

Seeking Safety is an evidence-based treatment for individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. This treatment shows promise to address the unique, unmet needs of women in prison. The current systematic literature review aims to highlight several critical gaps in research on Seeking Safety in forensic settings that need to be filled before Seeking Safety can be implemented in a widespread manner.

Methods

PsycINFO, PubMed and Google scholar databases were used to identify studies that were published in English, included women in forensic settings, and incorporated Seeking Safety treatment. A total of seven studies met review criteria. The quality of studies was assessed with the mixed methods appraisal tool.

Results

High risk of contamination, inclusion of small, predominantly White samples, high attrition rates, need for dose-response testing, and lack of follow-up data currently limit the ability to assess the efficacy of Seeking Safety in forensic settings. In addition, there is a lack of research on Seeking Safety’s ability to reduce symptoms of substance use disorder for incarcerated women and further cultural adaptation may be needed.

Conclusion

Seeking Safety has the potential to address the underlying causes of incarceration for justice-involved women, but additional research addressing these identified gaps is needed to facilitate more widespread implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Recent research has demonstrated that women are being incarcerated at a disproportionately increasing rate, even though the US prison population has seen a 25% decrease from 2011 (Carson 2022; Salina et al. 2011). In 2021, women represented almost 7% of the total prison population, up from 4% in 1978 (Carson 2022). One primary underlying cause of incarceration among women is substance use: “The war on drugs has inadvertently become a war on women, clearly contributing to the explosive increase in the number of women who are incarcerated” (Covington 1998, p.142). Consistent with this assertion, women are more likely to report using at least one drug at the time of arrest (Maruschak et al. 2021). Further, research suggests that women face unique barriers to treatment for substance use disorders, including greater perceived stigma (Agterberg et al. 2020), which may increase risk of continued use leading to incarceration. Salina et al. (2011) highlighted the exacerbated impact of incarceration on women, noting that these women are often the sole financial providers for their families, especially if they have children. Further, many leave the system without treatment for the underlying cause of their incarceration, increasing risk of recidivism.

Most women in incarceration also endorse a history of experiencing at least one traumatic event, conveying risk for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Simpson et al. 2021; Tripodi et al. 2020). Accordingly, both PTSD and substance use disorder (SUD) are more prevalent among justice-involved women compared to the general population (Zlotnick et al. 2003). Importantly, people with comorbid PTSD and SUD are usually less responsive to treatment, and the recovery process is complex given that PTSD and SUD “reciprocally reinforce” one another (Hien et al. 2021). In particular, symptoms of PTSD may be worsened by abstinence from substances (Hien et al. 2021). Moreover, while trauma-focused therapy is a strong intervention for PTSD, it may worsen symptoms of SUD and destabilize the client (Najavits 2007). As such, freely available treatments targeting PTSD and SUD simultaneously may be particularly impactful for people involved in the justice system (López-Castro et al. 2019; Zielinski et al. 2016).

Seeking Safety was developed by Lisa Najavits with the support of a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and was the first treatment designed to treat both PTSD and SUD simultaneously with published research support (Najavits 2003). The main goal of the treatment is to help clients establish safety—from substances, destructive relationships, etc.—which is considered the most urgent need of clients with these comorbidities (Najavits 2002). The integrated nature of Seeking Safety facilitates clients’ ability to accept both diagnoses, see the links between them, and understand how one triggers the other. Najavits also posits that a loss of ideals is characteristic of comorbid PTSD and SUD. Seeking Safety covers 25 topics to help clients attain safety by reconnecting clients with lost ideals and values (e.g., compassion, honesty, creating meaning, and discovery). It is manualized, present-focused, cost-effective, and applicable in a wide variety of situations (Najavits 2007). In addition, Seeking Safety can be administered individually or in a group setting, with varying session lengths and pace based on the clients’ needs, and in both inpatient and outpatient settings (Najavits 2007). This flexibility makes Seeking Safety particularly well suited to treatment of women who are incarcerated and who face notable barriers to accessing mental healthcare in this setting (Bright et al. 2022; Canada et al. 2022).

Seeking Safety has been recognized as an effective treatment by the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Practice Guidelines and is considered an encouraging intervention by the Society for Traumatic Stress Studies for comorbid PTSD and SUD (Forbes et al., 2020; Riggs & Foa, 2008; Wolff et al. 2012). A meta-analysis of 12 Seeking Safety treatment studies reported moderate effects on symptoms of PTSD and modest effects of treatment on symptoms of SUD (Gatz et al. 2007). In addition, a more recent meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of Seeking Safety found the treatment produced medium to large effects for symptoms of PTSD and small-to-medium effects for symptoms of SUD (Sherman et al. 2023). Seeking Safety has also demonstrated good effectiveness for clients with chronic disorders and multiple co-occurring life problems (Desai et al. 2008; Lenz et al. 2016). Researchers have begun to explore the efficacy and effectiveness of Seeking Safety in treatment for incarcerated women with promising results (Lynch et al. 2012; Tripodi et al. 2019; Wolff et al. 2012; Zlotnick et al. 2003).

To date, there are no established, evidence-based treatments that are commonly administered to women in prisons suffering from comorbid PTSD and SUD (Peters et al. 2017). Further, incarcerated women are rarely included in clinical research due to the complex nature of their living situation, changing conditions of safety, and severity of symptoms (Bright et al. 2022). The aim of the present review is to identify gaps in the literature that need to be filled to facilitate more widespread implementation of a treatment well suited to address comorbid symptoms of PTSD, Seeking Safety, and provide recommendations for how best to fill these gaps. While the small number of studies conducted to date precludes use of meta-analysis, the present systematic review will suggest how future research can address present limitations in the literature (including contamination, small sample sizes and high attrition rates, variable doses, predominantly White samples, need for follow-up studies, and more measurement of outcomes for SUD) with the hope that future research will facilitate more widespread implementation of this promising treatment for women involved in the criminal justice system in the USA.

Methods

Protocol and information sources

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al. 2021). PsycINFO, Pubmed, and Google Scholar were searched separately on the 27th of April 2022 to identify peer-reviewed literature and gray literature. To identify studies with the targeted intervention and population, the following search words were used: Google scholar ("Seeking safety" OR incarcerated OR women), PubMED (“Seeking Safety", women, prison) and PsycINFO (incarcerat* OR prison OR jail) AND (cognitive therapy OR trauma treatment OR cognitive behavioral therapy). In addition, the references sections for each included study, references sections for relevant reviews and meta-analyses, and the list of publications on the Seeking Safety website (Treatment Innovations 2020) were examined in an effort to identify additional studies for review. In an effort to improve the breadth of our search strategy, a separate search was conducted in October 2023 and the following search terms were added: “corrections,” “criminal justice,” and “justice-involved.” No additional studies were identified for inclusion in the present review.

Inclusion criteria

All treatment studies published in English evaluating Seeking Study for women in forensic settings were included. We included both peer-reviewed, published articles and the gray literature. We applied no restriction on the type of correctional institution, level of security clearance for participants, or the nature of the crimes. Moreover, no inclusion restrictions were made with respect to population age, study type, study outcomes, or comparators.

Search strategy

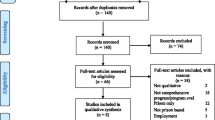

The original search was conducted on April 27, 2022. The first author and a research assistant evaluated articles for inclusion/exclusion criteria independently and discrepancies were discussed until consensus was obtained. This process was supervised by the second author. The first author conducted an additional search on October 26, 2023, and did not identify any more studies for inclusion. Figure 1 is a PRISMA flowchart detailing the study identification process used for this systematic review. During the full-text review, one article was removed because it was identified as a Department of Justice report for a pilot study which was published one year later (Zlotnick 2002; Zlotnick et al. 2003). A total of seven studies were included in the current review.

Quality assessment

The mixed-methods appraisal tool (MMAT) was used to evaluate the quality of the studies included in this systematic review. Given the variability in study designs, the authors chose the MMAT because it offers flexibility to appraise a variety of study methodologies and designs (qualitative, quantitative randomized controlled trial, quantitative nonrandomized, quantitative descriptive, and mixed methods; Hong et al. 2018). The MMAT evaluates risk of bias and quality of studies based on criteria that vary based on the type of study being evaluated. Studies included in the present review were quantitative randomized controlled trials and quantitative non-randomized studies. Quantitative randomized controlled trials were evaluated based on randomization, comparable groups at baseline, complete outcome data, single-blind assessments of outcome measures, and treatment adherence. Quantitative non-randomized studies were evaluated based on representativeness of the sample, appropriate measurement, complete outcome data, potential confounds, and appropriate administration of the intervention. We independently applied the tool to each included study and recorded supporting information and justifications for each domain of quality assessment (yes; no; cannot tell). Any discrepancies in judgements or their justifications were resolved by discussion to reach consensus between the two authors. Study quality is summarized in Table 1. Notably, the MMAT authors discourage use of an overall score in favor of a more nuanced presentation of study quality (Hong et al. 2018), so we chose not to include an overall score in Table 1. All studies demonstrated good quality in terms of appropriate sampling and randomization methods. Two of the three randomized controlled trials demonstrated comparable groups at baseline. All quantitative nonrandomized studies used appropriate measures. None of the studies provided sufficient evidence to confirm complete reporting of outcome data, such as pre-registration. Interpretation of results was commonly limited by potential confounds (n = 5) such as lack of blinding among outcome assessors in randomized controlled trials. Most studies demonstrated effective implementation of the intervention (n = 5), in terms of treatment adherence or sufficient evidence the treatment was administered as intended, with two unknown.

Results

Seven studies have been published evaluating Seeking Safety among justice-involved women: two quasi-experiments (Lynch et al. 2012; Wolff et al. 2012), three randomized controlled trials (Tripodi et al. 2019; Tripodi et al. 2020; Zlotnick et al. 2009), and two open trials (Holman et al. 2020; Zlotnick et al. 2003). These studies are summarized in Table 2. Notably, six studies showed positive results supporting the efficacy and effectiveness of Seeking Safety and one study reported null findings (Zlotnick et al. 2009). Meta-analysis would be most appropriate for assessment of Seeking Safety’s efficacy in treatment of women in the criminal justice system; however, more studies are needed for a sufficiently powered meta-analyses, especially given the preliminary nature of many of the studies included in this review (Jackson and Turner 2017). The results will therefore focus on evaluation of weaknesses in the literature (see Table 3) and make recommendations for future research.

A notable strength of the current literature is that all studies utilized group formats for administration of treatment. This facilitates comparison across studies. In addition, group treatment is highly advantageous for use in forensic settings, which are often limited in resources. Participants’ positive view of group treatment may also improve retention rates, a notable challenge for treatment of people in forensic settings (Zielinski et al. 2016). In addition, group treatments may maximize the impact of treatment by allowing participants to normalize their experiences and share their struggles with one another (Zielinski et al. 2016). For instance, participants noted that Seeking Safety led to increased feelings of group cohesion and reported “feeling safe and comfortable” in sharing their experiences (Wolff et al. 2012).

Additionally, the studies included in this review evaluated Seeking Safety in a variety of real-world settings, ranging from minimum to maximum security prisons, and reported promising outcomes, suggesting the potential for widespread implementation. Further, participants viewed Seeking Safety as favorable and reported high satisfaction rates (Wolff et al. 2012; Zlotnick et al. 2009). Taken together, current research on Seeking Safety is promising; however, additional research is needed to address several limitations to better inform more widespread implementation of this treatment for women who are incarcerated.

Contamination

The potential for contamination between conditions was noted by several studies (Lynch et al. 2012; Tripodi et al. 2019; Zlotnick et al. 2009). Lynch et al. (2012) found evidence of contamination; they learned that participants were sharing handouts and group materials with others in their cell blocks. Similarly, Tripodi et al. (2019) and Zlotnick et al. (2009) acknowledged the high risk of contamination in their studies given close living spaces as well as the sense of camaraderie among the women. This contamination reflects the positive interest in Seeking Safety among women in the criminal justice system but could result in underestimates of treatment efficacy. While controlling for contamination can prove to be difficult in forensic settings, none of the studies reported any attempts to control for contamination across groups. Future studies may include psychoeducation about the importance of not sharing materials during the consent process and following every session. Additionally, future researchers may offer alternative treatments as opposed to using waitlist control groups, conduct different treatment conditions in different units, and/or offer Seeking Safety to women in waitlist control groups after the end of the treatment period (assuming recruitment of women with sufficiently long sentences or telehealth options for women who have left the original prison setting, if feasible). Alternatively, researchers can modify the treatment protocol to include and encourage sharing of materials, not only to maximize the impact of the treatment in a limited-resource setting, but also to normalize people’s traumatic experiences and struggles (Karlsson et al. 2015; Zielinski et al. 2016). Group members may potentially feel empowered when given the opportunity to support others with common struggles. In addition, this sharing of materials may reduce stigma associated with psychological treatment. These outcomes could be measured.

Small sample sizes and high attrition rates

Studies evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of Seeking Safety for women in prison have been characterized by small sample sizes and may be underpowered. Five studies reported fewer than 50 participants who completed the study (Holman et al. 2020; Tripodi et al. 2019; Tripodi et al. 2020; Zlotnick et al. 2003; Zlotnick et al. 2009). While we expect pilot studies to have small sample sizes, it limits the extent to which data can inform the efficacy of Seeking Safety for women in forensic settings.

A major challenge that can contribute to small samples in this field is attrition, which was particularly high for three of the included studies (30% in Lynch et al. 2012; approximately 50% in Tripodi et al. 2020; and 33% in Wolff et al. 2012). We defined a high attrition rate as 30% or greater based on the findings of a systematic review conducted by Lipsey et al. (2007), which examined moderators of the effect of CBT on recidivism in general offender populations. For the 58 studies included in their review, the attrition rate was found to range from “virtually zero” to over 30%. Among the other studies included in the present review, attrition rates ranged from 11% (Zlotnick et al. 2003) to 25% (Tripodi et al. 2019). Holman et al. (2020) did not report an attrition rate.

High attrition rates may be expected given the nature of a forensic population. Wolff et al. (2012) noted high attrition in their study was typically the result of factors outside the researchers’ control, including relocations, confinement due to violation of rules, disinterest, and scheduling conflicts. Tripodi et al. (2019) and Holman et al. (2020) reported similar reasons for dropout in their studies, including administrative decisions over which the researchers had no influence. Despite a high attrition rate, Lynch et al. (2012) had the biggest sample size of 114 women. These authors did not randomly assign participant to condition. Instead, they chose to assign participants by prison staff’s recommendations based on anticipated release or transfer dates. Although this technique is clever and possibly the reason for a larger sample size, it introduces an alternative explanation for positive findings; Seeking Safety participants had earlier transfer or release dates and it may have been the anticipation of release that contributed to positive change. As such, researchers may benefit from utilizing a strategy similar to Lynch et al. (2012) in future work, but they are encouraged to identify participants with comparable release dates when allocating participants to conditions.

Dose

Given the high risk of attrition associated with a prison population, streamlining Seeking Safety in a way that maximizes benefit and minimizes number of sessions or “dose” is important for more widespread benefit to this population. Sherman et al. (2023) conducted a dose-response analysis as part of their meta-analysis and found that a partial dose of Seeking Safety was comparable to the full dose for long-term effects, which they defined as longer than 3 months. However, the minimum “dose” of Seeking Safety remains unclear. There was considerable variability in the number of Seeking Safety sessions offered and attended by participants across studies included in this review. Among studies that reported session attendance, participants only received 14–18 sessions of treatment, on average (Lynch et al. 2012; Wolff et al. 2012; Zlotnick et al. 2003; Zlotnick et al. 2009). Five studies offered the full dose of treatment (at least 24 sessions) to their participants (Lynch et al. 2012; Tripodi et al. 2019; Wolff et al. 2012; Zlotnick et al. 2003; Zlotnick et al. 2009). The remaining two studies offered abbreviated versions of Seeking Safety but did not report the average number of sessions attended. Holman et al. (2020) offered a total of eight sessions, occurring once a week for 8 weeks. Tripodi et al. (2020) offered a total of 12 sessions occurring twice weekly over a period of 6 weeks. Both of these abbreviated interventions were associated with positive outcomes and large effect sizes.

Given the many factors contributing to high attrition rates among women who are incarcerated and the wide range of average number of sessions present in the literature, complete dose-response testing is needed for this population. Further, future efforts to streamline Seeking Safety would be best informed by identification of the mechanisms of change associated with this treatment and the aspects of treatment that target these mechanisms most effectively (see Kazdin 2007 for a relevant discussion on treatment mechanisms).

Predominantly White samples

Five out of the seven studies included in this review had predominantly White samples, with at least 60% of participants identifying as White (Holman et al. 2020; Lynch et al. 2012; Tripodi et al. 2019; Tripodi et al. 2020; Zlotnick et al. 2003). Lynch et al. (2012) reported that 84% of their participants were White, which was representative of the local region. Holman et al. (2020) noted that most of the prisoners at the time of study were White and that their counselors were White. This predominance of White participants in these studies’ samples limits the generalizability of these studies’ findings, especially because it is representative of neither the criminal justice system nor the composition of American society overall. Furthermore, examining the effectiveness of Seeking Safety for People of Color living in forensic settings is crucial. People of Color are inequitably targeted by the criminal justice system and are overrepresented in prison populations (Carson 2022; Jeffers 2019; Nellis 2021). Research shows that culturally relevant assessment and treatment by culturally competent and humble clinicians are needed to maximize treatment outcomes for People of Color with PTSD (McClendon et al. 2020). In future studies, researchers are encouraged to include and describe a multicultural population with diverse identities in terms of race, gender identity, sexual identity, class, and disability, among other factors. Recommendations for recruitment strategies that may facilitate inclusion of diverse samples in trauma-focused research are described in Williams et al. (2020), and recommendations for recruitment in forensic settings are described in Zielinski et al. (2016).

Lack of follow-up data

Three studies collected follow-up data and support potential long-term benefits of Seeking Safety among justice-involved women. Zlotnick et al. (2003) reported maintenance of improvement in PTSD symptoms at a three-month follow-up assessment. Zlotnick et al. (2009) collected follow-up data at three months and six months post-release and found improvement at each time point for both PTSD symptoms and SUD symptoms. Tripodi et al. (2019) reported greater improvement for the Seeking Safety treatment group in symptoms of PTSD at a four-month follow-up assessment.

Four out of seven outcome studies did not collect follow-up data (Lynch et al. 2012; Wolff et al. 2012; Holman et al. 2020; Tripodi et al. 2020). Notably, collection of long-term follow-up data may be particularly important for evaluating the effect of Seeking Safety on improving functioning and quality of life for women post-incarceration as well as evaluating the effect of treatment on recidivism. Offering booster sessions for women post-treatment is one potential solution for evaluation of long-term outcomes, as women are less likely to be lost to follow-up if they continue to engage with treatment post-release (Zlotnick et al. 2009). Booster sessions may also lessen the high rates of recidivism (Zlotnick et al. 2003) and promote generalization of skills learned in Seeking Safety to post-release contexts. Additional strategies that may promote collection of long-term follow-up data are discussed by Hill et al. (2016).

Lack of data on efficacy of Seeking Safety for symptoms of SUD

Finally, more research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of Seeking Safety in reducing primary symptoms of SUD for justice-involved women. Five of the seven studies did not measure changes in symptoms of SUD (Holman et al. 2020; Lynch et al. 2012; Tripodi et al. 2019; Tripodi et al. 2020; Wolff et al. 2012). Lynch et al. (2012) did not measure substance use because women in incarceration allegedly did not have access to substances. However, the prohibition of the use of substances does not guarantee that no substances were being used, nor that the urge to use was not experienced. Wolff et al. (2012) reported that they did not collect data on symptoms of SUD because the researchers were required to report use of any substances. While this behavior is ethical, it defeats the purpose of evaluating Seeking Safety as an integrated treatment for comorbid PTSD and SUD. Measuring symptoms such as changes in addiction-related thinking and readiness for change, as suggested by Wolff et al. (2012), or measuring participants’ urge to use substances while women are in incarceration, and collecting explicit information on substance use post-release as part of the longitudinal studies may be a useful way to gather data on SUD symptoms.

Some researchers were able to assess SUD outcomes, but their findings demonstrated limited efficacy. Zlotnick et al. (2009) recruited participants from an evidence-based substance use treatment ward of a women’s prison and found no significant differences in reduction of frequency of substance use between Seeking Safety and treatment as usual. Null results could be due to contamination across conditions given the nature of the treatment setting. Zlotnick et al. (2003) found that six out of 17 women reported use of illegal substances within three months of release from prison. Notably, once women are released from prison, they likely have different lifestyles and different exposure to cues and triggers that could reinforce substance use behaviors. Thus, adaptations to Seeking Safety for women in incarceration such as skills coaching or booster sessions post-release may be needed to promote generalization of skills learned while in prison.

Discussion

Seeking Safety is a promising treatment to address the unique needs of justice-involved women because it is one of very few integrated treatments with efficacy data and it is accepted widely by women in prison as well as prison authorities (Wolff et al. 2012; Zlotnick et al. 2003). This treatment is easy to administer and cost-effective, and studies report high group cohesion when it is administered in group settings (Lynch et al. 2012; Zlotnick et al. 2009). However, the current state of the literature on the efficacy of Seeking Safety in forensic settings is currently sparse with limited reproducibility. Conclusive findings on the efficacy and effectiveness of this treatment could improve the likelihood of more widespread use. The present review makes recommendations for how future studies might fill current gaps in the literature. This is an urgent and critical need (Norris et al. 2022; Zielinski et al. 2023).

In addition, current research on Seeking Safety for justice-involved women suggests cultural adaptation of this treatment is warranted. Lenz et al. (2016) found the greatest treatment effects for White participants relative to racially and ethnically minoritized participants. In contrast, Wolff et al. (2012) found similar improvements in PTSD symptoms for White and African American women as well as comparable improvements in symptom severity for White and Hispanic participants, indicating potential benefit of Seeking Safety for People of Color. We contend that cultural adaptation of Seeking Safety is important for maximizing the benefits this treatment may convey for women in prison settings with minoritized racial and ethnic identities. Further, the culture in prison settings is unique and may require adaptations above and beyond those commonly used for treatment of People of Color. Bernal et al.'s (1995) Ecological Validity Model offers a helpful framework that may be used to guide cultural adaptation. Methodological approaches that invite stakeholders to join in the development of said cultural adaptations is also highly recommended (e.g., Hwang 2009). In addition, Zielinski et al. (2016) offer valuable insights into how trauma-focused treatments might best be adapted for treatment of incarcerated women.

Another factor that may play a role in the cultural applicability of Seeking Safety for women in the criminal justice system is the language in which the treatment is administered. Even though a Spanish version of the treatment manual was published in 2006, all studies evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of Seeking Safety for women in prison included in the present review have been conducted in English, and fluency in English was listed as an inclusion criterion for five studies (Lynch et al. 2012; Tripodi et al. 2020; Wolff et al. 2012; Zlotnick et al. 2003; Zlotnick et al. 2009). Consistent with the APA ethical principle of justice, the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1964, and legal requirements to offer interpreter services in healthcare settings, future studies will need to offer this treatment in languages other than English (APA 2017; Diamond et al. 2010; Ku and Flores 2005). With a considerable Spanish-speaking population in the justice system, implementation of the Spanish manual is warranted.

Despite our efforts to include qualitative research studies in the current review, none were identified in our search. The literature on Seeking Safety could benefit greatly from qualitative research evaluating multiple perspectives, including but not limited to treatment group facilitators, study supervisors, prison staff, and administration. This research may be particularly important for informing cultural adaptations to treatment and challenging stigma against people who have experienced incarceration, among other benefits (Willig 2019).

There are several notable limitations of this review. First, we only included literature published in English. Given that the Seeking Safety manual has been published in multiple languages, it is possible that there are studies assessing the intervention for women in incarceration that were not included in our review. Second, most studies included in our review are preliminary in nature. While preliminary studies provide valuable insights in assessing the feasibility and effectiveness of Seeking Safety, more controlled trials and meta-analyses are required to evaluate this treatment as a viable option. Third, the generalizability of our findings is limited given the small number of studies available that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Despite these limitations, we hope this review will inspire researchers to continue to explore different ways to improve and evaluate the efficacy of Seeking Safety as a treatment for justice-involved women. Moreover, we hope that this work will address some of the underlying causes for incarceration and benefit the lives of justice-involved women.

References

Agterberg S, Schubert N, Overington L, Corace K (2020) Treatment barriers among individuals with co-occurring substance use and mental health problems: examining gender differences. J Subst Abus Treat 112:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.01.005

American Psychological Association (2017) Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C (1995) Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. J Abnorm Child Psychol 23(1):67–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01447045

Bright AM, Higgins A, Grealish A (2022) Women's experiences of prison-based mental healthcare: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Int J Prison Health 19(2):181–198. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-09-2021-0091

Canada K, Barrenger S, Bohrman C, Banks A, Peketi P (2022) Multi-level barriers to prison mental health and physical health care for individuals with mental illnesses. Front Psych 13:777124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.777124

Carson E (2022) Prisoners in 2021 – statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisoners-2021-statistical-tables

Covington SS (1998) Women in prison: approaches in the treatment of our most invisible population. Women Ther 21(1):141–155. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015v21n01_03

Desai RA, Harpaz-Rotem I, Najavits LM, Rosenheck RA (2008) Impact of the seeking safety program on clinical outcomes among homeless female veterans with psychiatric disorders. Psych Serv (Washington, D.C.) 59(9):996–1003. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.9.996

Diamond LC, Wilson-Stronks A, Jacobs EA (2010) Do hospitals measure up to the national culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards? Med Care 48(12):1080–1087. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f380bc

Forbes D, Bisson JI, Monson CM, Berliner L (2020) Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 3rd edn. The Guilford Press

Gatz M, Brown V, Hennigan K, Rechberger E, O'Keefe M, Rose T, Bjelajac P (2007) Effectiveness of an integrated, trauma-informed approach to treating women with co-occurring disorders and histories of trauma: the Los Angeles site experience. J Community Psychol 35(7):863–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20186

Hien DA, López-Castro T, Fitzpatrick S, Ruglass LM, Fertuck EA, Melara R (2021) A unifying translational framework to advance treatment research for comorbid PTSD and substance use disorders Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 127:779–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.05.022

Hill KG, Woodward D, Woelfel T, Hawkins JD, Green S (2016) Planning for long-term follow-up: strategies learned from longitudinal studies. Prevention Science: Official J Soc Prevention Res 17(7):806–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0610-7

Holman LF, Ellmo F, Wilkerson S, Johnson RS (2020) Quasi-experimental single- subject design: comparing Seeking Safety and canine-assisted therapy interventions among mentally ill female inmates. J Addict Offender Couns 41(1):35–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaoc.12074

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’Cathain A, Rousseau M-C, Vedel I (2018) Mixed methods sppraisal tool (MMAT). Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada.http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf

Hwang W-C (2009) The formative method for adapting psychotherapy (FMAP): a community-based developmental approach to culturally adapting therapy. Prof Psychol Res Pract 40(4):369–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016240

Jackson D, Turner R (2017) Power analysis for random-effects meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 8(3):290–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1240

Jeffers JL (2019) Justice is not blind: disproportionate incarceration rate of people of color. Soc Work Public Health 34(1):113–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2018.1562404

Karlsson ME, Zielinski MJ, Bridges AJ (2015) Expanding research on a brief exposure-based group treatment with incarcerated women. J Offender Rehabil 54:599–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2015.1088918

Kazdin AE (2007) Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 3:1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432

Ku L, Flores G (2005) Pay now or pay later: providing interpreter services in health care. Health Aff 24(2):435–444. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.435

Lenz AS, Henesy R, Callender K (2016) Effectiveness of Seeking Safety for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use. J Couns Dev 94(1):51–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12061

Lipsey MW, Landenberger NA, Wilson SJ (2007) Effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for criminal offenders. Campbell Syst Rev 3(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2007.6

López-Castro T, Smith KZ, Nicholson RA, Armas A, Hien DA (2019) Does a history of violent offending impact treatment response for comorbid PTSD and substance use disorders? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J Subst Abus Treat 97:47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.11.009

Lynch SM, Heath NM, Mathews KC, Cepeda GJ (2012) Seeking safety: an intervention for trauma-exposed incarcerated women? J Trauma Dissociation 13(1):88–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2011.608780

Maruschak L, Bronson J, Alper M (2021) Alcohol and drug use and treatment reported by prisoners. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Office of Justice Programs. https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/adutrpspi16st.pdf

McClendon J, Dean KE, Galovski T (2020) Addressing diversity in PTSD treatment: disparities in treatment engagement and outcome among patients of color. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 7:275–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-020-00212-0

Najavits LM (2002) Seeking safety: a treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. Guilford Press

Najavits LM (2003) Seeking safety: a new psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. In: Ouimette P, Brown PJ (eds) Trauma and substance abuse: causes, consequences, and treatment of comorbid disorders. American Psychological Association, pp 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/10460-008

Najavits LM (2007) Seeking safety: an evidence-based model for substance abuse and trauma/PTSD. In: Witkiewitz KA, Marlatt GA (eds) Therapist's guide to evidence-based relapse prevention. Academic Press, pp 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012369429-4/50037-9

Nellis A (2021) The color of justice: racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/the-color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons-the-sentencing-project/

Norris WK, Allison MK, Fradley MF, Zielinski MJ (2022) 'You're setting a lot of people up for failure': what formerly incarcerated women would tell healthcare decision makers. Health & Justice 10(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-022-00166-w

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Peters RH, Young MS, Rojas EC, Gorey CM (2017) Evidence-based treatment and supervision practices for co-occurring mental and substance use disorders in the criminal justice system. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 43(4):475–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2017.1303838

Riggs DS, Foa EB (2008) Treatment for co-morbid posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders. In Stewart SH, Conrod PJ (eds) Anxiety and substance use disorders: The vicious cycle of comorbidity. Springer Science + Business Media. pp 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-74290-8_7

Salina DD, Lesondak LM, Razzano LA, Parenti BM (2011) Addressing unmet needs in incarcerated women with co-occurring disorders. J Soc Serv Res 37(4):365–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2011.582017

Simpson TL, Goldberg SB, Louden DKN, Blakey SM, Hawn SE, Lott A, Browne KC, Lehavot K, Kaysen D (2021) Efficacy and acceptability of interventions for co-occurring PTSD and SUD: a meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord 84:102490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102490

Sherman ADF, Balthazar M, Zhang W, Febres-Cordero S, Clark KD, Klepper M, Coleman M, Kelly U (2023) Seeking safety intervention for comorbid post-traumatic stress and substance use disorder: a meta-analysis. Brain Behav 13(5):e2999. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2999

Treatment Innovations (2020) Seeking Safety. https://www.treatment-innovations.org/evid-all-studies-ss.html

Tripodi SJ, Mennicke AM, McCarter SA, Ropes K (2019) Evaluating Seeking Safety for women in prison: a randomized controlled trial. Res Soc Work Pract 29(3):281–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731517706550

Tripodi SJ, Killian MO, Gilmour M, Curley EE, Herod L (2020) Trauma-informed care groups with incarcerated women: an alternative treatment design comparing Seeking Safety and STAIR. J Soc Soc Work Res 13:657–676. https://doi.org/10.1086/712732

Williams MT, Reed S, Aggarwal R (2020) Culturally informed research design issues in a study for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychedelic Stud 4(1):40–50. https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2019.016

Willig C (2019) What can qualitative psychology contribute to psychological knowledge? Psychol Methods 24(6):796–804. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000218

Wolff N, Frueh BC, Shi J, Schumann BE (2012) Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral trauma treatment for incarcerated women with mental illnesses and substance abuse disorders. J Anxiety Disord 26(7):703–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.06.001

Zielinski MJ, Karlsson ME, Bridges AJ (2016) Adapting evidence-based trauma treatment for incarcerated women: a model for implementing exposure-based group therapy and considerations for practitioners. Behav Ther 39(6):205–210

Zielinski MJ, Allison MK, Smith MKS, Curran G, Kaysen D, Kirchner JE (2023) Implementation of group cognitive processing therapy in correction centers: anticipated determinants from formative evaluation. J Trauma Stress 36(1):193–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22898

Zlotnick C (2002) Treatment of incarcerated women with substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder, final report. Office of Justice Programs https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/195165.pdf

Zlotnick C, Najavits LM, Rohsenow DJ, Johnson DM (2003) A cognitive-behavioral treatment for incarcerated women with substance abuse disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a pilot study. J Subst Abus Treat 25(2):99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00106-5

Zlotnick C, Johnson J, Najavits LM (2009) Randomized controlled pilot study of cognitive-behavioral therapy in a sample of incarcerated women with substance use disorder and PTSD. Behav Ther 40(4):325–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.09.004

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Alex De La Rosa for double-coding methods.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Agarwal, I., Draheim, A.A. Seeking Safety for women in incarceration: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health 27, 317–327 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-023-01411-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-023-01411-3