Abstract

Purpose

Given the health consequences, perinatal substance use is a significant public health concern, especially as substance use rates increase among women; ongoing data regarding the rates of substance use across trimesters of pregnancy is needed.

Methods

The present study utilized cross-sectional population-based data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) between 2009 and 2019. We aimed to explore both licit and illicit substance use assessed within each trimester among women endorsing past-year substance use. The NSDUH sample included 8,530 pregnant women.

Results

Perinatal substance use was less prevalent among women in later trimesters; however, past-month substance use was observed for all substances across trimesters. The prevalence of past-month licit substance use among pregnant women ranged from 5.77 to 22.50% and past-month illicit substance use ranged from 4.67 to 14.81%. In the second trimester, lower odds of past-month substance use were observed across tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana (odds ratios [ORs] ranging from 0.29 to 0.47), when compared to the first trimester. A similar lower rate of past-month substance use was observed in the third trimester compared to the first trimester, across tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use, as well as cocaine, prescription pain medication, and tranquilizer use (ORs ranging from 0.02 to 0.42). The likelihood of polysubstance use was lower among women in the second and third trimesters compared to the first trimester (ORs ranging from 0.09 to 0.46).

Conclusion

Findings indicate that a minority of women continue to use substances across all trimesters. This is especially true among women using licit substances and marijuana. These results highlight the need for improved interventions and improved access to treatment for these women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Substance use is a widespread problem across the United States (US) and while data suggest that many women discontinue substance use during pregnancy, a subset of women are unable to abstain from use during the perinatal period (Grant et al. 2016; Massey et al. 2011; McHugh et al. 2014; Qato et al. 2020). The discontinuation rate during pregnancy varies by drug of abuse; recent reports indicate problematic patterns of use of licit substances (tobacco, alcohol), cannabis, and the co-use of these substances among pregnant women (Alshaarawy and Anthony 2019; Massey et al. 2011; Qato et al. 2020; SAMSHA 2015; Shmulewitz and Hasin 2019; Young-Wolff et al. 2017). Approximately 14% of pregnant women endorsed past-month tobacco use in 2015, compared to 11.9% endorsing past-month use in 2014 (SAMSHA 2015). Similarly in 2015, 9.3% of pregnant women endorsed alcohol use over the past month, while 8.8% endorsed the same drinking pattern in 2014 (SAMSHA 2015), and increased odds of drinking was observed among co-use of other substances (Shmulewitz and Hasin 2019). Additionally in a recent study, 19% of pregnant women aged 18 to 24 years old and 5.1% of those 25–34 years old screened positive for cannabis use either through self-report or toxicology tests (Young-Wolff et al. 2017) and increasing rates of cannabis-related hospitalizations during pregnancy have been observed in states that have legalized recreational cannabis (Wang et al. 2022). Such figures represent a growing clinical and public health concern regarding trends in perinatal substance use.

These substance use rates are especially alarming as prenatal substance use presents extensive health consequences and negative birth outcomes for the neonate (Forray, 2016). These adverse effects range from blunted fetal growth to cognitive deficits; there are also multiple potential pregnancy/birth complications and increased risk of infant mortality (for review see Forray 2016). In addition to significant health consequences for the neonate, prenatal substance use is associated with substantial health implications and medical complications for the mother (Forray, 2016). For instance, tobacco use is associated with increased risk of miscarriage and maternal cocaine use is associated with premature rupture of the membrane and increased odds of negative placenta outcomes and abnormalities (Addis et al. 2001; Pineles et al. 2014; Salihu and Wilson 2007). Additional risks associated with substance use during the perinatal period are pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders, as well as increased risk of infection, and other negative health outcomes (Berenson et al. 1995; Gorman et al. 2014; Hudak and Tan 2012; Minozzi et al. 2013; Sokol et al. 2003).

Such pregnancy related complications, including perinatal and delivery complications, have been implicated as contributing factors to maternal deaths (Centers of Disease Control and Prevention 2019; Singh 2021; Trost et al. 2021). This is important considering that maternal deaths have more than doubled in the US in recent years (MacDorman et al. 2016) and there have been considerable increases in maternal mortalities, related to self-harm and substance use (Mangla et al. 2019). In fact, one study found that a large percentage of maternal deaths (among 421 pregnancy related deaths across 14 states) occurred among women with lifetime or current substance use (Trost et al. 2021). Similarly, another study exploring maternal-related deaths in California between 2010 and 2012 found that drug-related causes were the second leading cause of maternal death. These drug-related causes included ICD-10 codes for accidental poisonings, drug-induced disease, drugs in blood, and behavioral disorders related to drug use; this amounted to 18% of maternal deaths in California being attributed to substance use (Goldman-Mellor and Margerison 2019).

It should be noted when discussing drug-related maternal death that there is a range of pregnancy-related substance use consequences (Forray, 2016) and that there is some discord regarding the amount, if any, of a substance (e.g., alcohol), that should be consumed during pregnancy (Oh et al. 2017). While this discord falls outside the scope of the current paper, it is important to acknowledge that recent data illustrates increases in substance use among women of childbearing age (Grant et al. 2017, 2016). These increased rates of substance use, coupled with increases in drug-related maternal deaths, highlight the need for additional research exploring maternal substance use in order to improve the health of women.

Previous research has shown that substance use during pregnancy, generally decreases between trimesters (e.g., Ebrahim and Gfroerer 2003; Forray et al. 2015; Massey et al. 2011; Oh et al. 2017; Tong et al. 2008). It appears that there are higher decreases in rates of alcohol and illicit/recreational drug use than in rates of tobacco and marijuana, which remain more consistent across trimesters (Moore et al. 2010). This is problematic given the high rate of co-use of marijuana and tobacco among pregnant women, as these women report more high-risk behaviors than their abstaining or single substance using counterparts (Coleman-Cowger et al. 2017; Moore et al. 2010; Qato et al. 2020).

Research has demonstrated that women are less likely to achieve pregnancy-related abstinence from cigarettes and are more likely to abstain from alcohol use while pregnant compared to marijuana or cocaine (Forray et al. 2015). This is concerning given the recent increases in tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use during pregnancy, as well as rising rates of maternal mortality (Mangla et al. 2019; Massey et al. 2011; SAMSHA 2015; Shmulewitz and Hasin 2019; Soneji and Beltrán-Sánchez 2019; Young-Wolff et al. 2017). However, much of the information to date explores the change in substance use over the course of pregnancy within smaller sample populations (e.g., Forray et al. 2015; Best et al. 2009; Latuskie et al. 2019). Replication of such changes in perinatal substance use across licit/illicit substances within a recent, large epidemiological dataset would provide valuable, up-to-date data, which may inform health service delivery and improve effective interventions among pregnant women using substances. Conducting a study to explore licit/illicit substances across pregnancy in a single national dataset will provide researchers, providers, and policy makers with valuable data that is powered to observe clinically significant changes across pregnancy, as a large national data set improves generalizability via limiting variable definitions of substance use, sampling biases, and differences in study procedures (Lester et al. 2004; Oh et al. 2017). There is no recent national data available regarding perinatal substance use across trimesters; the last available published data was from 2005–2014 and these studies explore alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and co-use of substances (Oh et al. 2017; Qato et al. 2020; Shmulewitz and Hasin 2019). Data of both illicit and licit substances across the trimesters is especially important as alcohol and drug use rates are increasing for women of childbearing age (Grant et al. 2016, 2017). It would be beneficial for a study to explore alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and other illicit/licit substances (including opioids, sedatives, hallucinogens, and other drugs) in each trimester. This information would provide needed information to further tailor screenings, interventions, and policy to improve the health of women and neonates.

The present study

The present study sought to update perinatal substance use research and explore the association between substance use (including alcohol, tobacco, and other illicit substance use) and trimester in a representative national sample across the past decade. It was hypothesized that in the second and third trimesters, rates of substance use would be lower, but would not be completely eliminated. Furthermore, it was hypothesized that a greater reduction among illicit substances would be observed in the second and third trimesters versus the first trimester.

Materials and methods

Study data

Data utilized in the present study was from the annual waves (2009–2019) of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which was administered nationally by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA). This annual survey collects cross sectional data on alcohol and drug abuse, as well as other health-related factors, in a nationally representative sample of noninstitutionalized US civilians. The final sample included 8,530 pregnant women. A more detailed description of the survey methodology is available elsewhere (SAMSHA 2016).

Measures

Demographic variables

The present survey assessed sociodemographic variables including age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment, and income. Of note in 2015, questions assessing marital status, education, and employment were altered to provide additional detail; while these variables were represented by a different variable name in the public dataset, they were recoded to identically matched data sets from preceding and subsequent years (SAMSHA 2015, 2016, 2018). Thus, this variable was combined with the equivalent variables from years 2009–2014 and 2015–2019. Pregnancy was assessed by asking women survey respondents if they were pregnant. Furthermore, women who self-reported being pregnant reported the trimester of their pregnancy.

Substance use

Substance use was assessed by utilizing variables that queried alcohol, tobacco, and illicit substance use in the past year and past month. Variables were derived from the recency of use questions to represent respondents who have used alcohol, tobacco, and illicit substances (including: marijuana, cocaine, heroin, inhalants, and hallucinogens, as well as illicit/recreational use of prescription pain medication, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives) in the past eleven months, but stopped or continued use over the past month. Of note, variables surrounding cigars, cigarettes, and smokeless tobacco were combined to compute a tobacco recency variable. Furthermore, variables detailing recency of methamphetamine and prescription stimulant use were also combined to compute a stimulant use recency variable. Composite variables of licit substance use (e.g., alcohol and tobacco) and illicit substance use were also computed, as were rates of polysubstance use for individuals using 1 + , 2 + , and 3 + substances. Some drug variables had the survey question language altered in specific years (e.g., 2015); however, answers regarding recency of use remained identical; such variables were combined to represent that substance’s use across the decade. Additionally, analysis combined use over the past eleven months and use over the past 30 days to create the “past-year” variable.

Statistical analysis

Data utilized in the present study is cross-sectional. Among the pregnant women reporting past-year substance use, demographic variables and past-month substance use were calculated for each trimester to explore changes in substance use across the trimesters. Adjusted logistic regressions were conducted to examine the change in substance use in the past month across trimesters (reference group, first trimester) among pregnant women endorsing past-year substance use. Adjusted analyses included age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, and household income as covariates. Logistic regression analyses were weighted and accounted for the NSDUH survey design, including stratification, clustering (i.e., primary sampling unit), and unequal weighting of the sampling design.

Results

Sociodemographic

Of the respondents endorsing current pregnancy (n = 8,530) and past-year substance use (31.53% first trimester, 36.44% second trimester, 32.03% third trimester), participants were primarily White (56.18–57.79%). Most participants fell into the 18- to 25-year-old age category (32.24–35.64%) and reported being married (57.68–60.67%). The majority of individuals endorsed at least completing high school (70.22–84.66%). Additionally, most participants self-identified as working full time (38.68–47.75%) and earning over $20,000 annually (78.45–78.83%). See Table 1 for complete sociodemographic results by trimester.

Substance use across trimesters

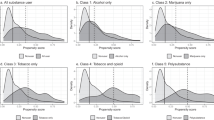

Table 2 presents past-year and past-month prevalence for substance use across the first, second, and third trimesters among women endorsing past-year substance use. Women who reported using licit substances (alcohol and tobacco) within the past month across trimesters (ranging from 5.77 to 22.50%) showed a decreasing pattern of use in the second and third trimesters. A similar pattern emerged regarding past-month tobacco use (ranging from 47.51 to 61.93%), with past-month use also decreasing in the second and third trimesters. Past-month use of alcohol (ranging from 6.16 to 26.83%) also was lower in the later trimesters. While there were significant decreases, a subset of women across all three trimesters continued to use licit substances.

Rates of past-month illicit substance use (ranging from 4.67 to 14.81%) were lower in the second and third trimesters. For example, past-month use of marijuana (ranging from 25.97 to 43.63%) was lower in the second and third trimester; however as observed with licit substances, a subset of women in all three trimesters endorsed past-month use. Polysubstance use (1 + drugs) ranged from 7.78 to 31.34% across the trimesters, again with use tapering in the second and third trimester for most pregnant women with past-year substance use. Complete data regarding rates of substance use can be found in Table 2.

Results indicated that across a variety of substances, the odds of both past-month licit and illicit substance use were lower in the second trimester (licit OR = 0.29, CI = 0.21–0.40; illicit OR = 0.40, CI = 0.30–0.53) and the third trimester (licit OR = 0.20, CI = 0.14–0.30; illicit OR = 0.23, CI = 0.21–0.38), compared to the first trimester. Specifically, past-month use of tobacco (OR = 0.47, CI = 0.34–0.65), alcohol (OR = 0.27, CI = 0.21–0.35), and marijuana (OR = 0.43, CI = 0.31–0.60) was lower in the second trimester compared to the first trimester among women reporting past-year substance use. Additionally, polysubstance use (1 + drug of use) also was lower in the second trimester compared to the first (ORs range from 0.21–0.44). In fact, among those endorsing polysubstance use, in the third trimester, over 90% of women quit use.

The odds of past-month use also were lower in the third trimester, compared to the first trimester for several substances, including tobacco (OR = 0.41, CI = 0.30–0.58), alcohol (OR = 0.18, CI = 0.13–0.26), marijuana (OR = 0.41, CI = 0.28–0.60), cocaine (OR = 0.02, CI = 0.00 = 0.18), prescription pain medication (OR = 0.42, CI = 0.18–097), and tranquilizers (OR = 0.14, CI = 0.03–0.67). Additionally, the odds of past-month polysubstance use (1 + drugs of use) also were lower as in the second and third trimesters in comparison to the first trimester (ORs = 0.17–0.46). See Table 3 for complete results.

Discussion and conclusions

Using a large epidemiological dataset, the present study demonstrated that perinatal use of most licit and illicit substances decreases as pregnancy moves into the later trimesters, among pregnant women with a history of past-year substance use. Pregnant women who reported past-year drug use had lower odds of reporting past-month drug use in the second and third trimesters when compared to the first trimester among a range of substances including tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, tranquilizers, and stimulants. Additionally, among those endorsing polysubstance use, in the third trimester, over 90% of women quit use; however, despite this promising quit rate, past-month substance use was observed throughout all three trimesters of pregnancy. This data is valuable as substance use among women of childbearing age is increasing (Grant et al. 2016; Grant et al. 2017); the present study provides the ongoing, nationally representative data needed to describe substance use in pregnant women given the rise of overall substance use among women.

The present study is consistent with previous research demonstrating differences in substance use between trimesters, with an overall decrease in substance use following the first trimester (Moore et al. 2010; Oh et al. 2017; Tong et al. 2013). Most pregnant women achieve abstinence in the second trimester, with one study reporting that approximately 60% of women stopped drinking once they recognized that they were pregnant (Forray et al. 2015; O’Connor and Whaley 2003). It has been postulated that recognizing pregnancy status may reduce maternal substance use, as women may consume substances before knowing they are pregnant. However, the current study was only able to explore the odds of past-month substance use in females who knew they were pregnant, and first trimester substance use rates remained high. Although it should be noted there may be a small percentage of women who has past-month use may have coincided with a time prior to knowledge of their pregnancy. Nonetheless, it is likely that additional mechanisms outside of the knowledge of the pregnancy impact this decrease in substance use among pregnant women and further investigation is warranted.

Results indicate that tobacco remains the most used substance across trimesters. This is problematic, as behavioral interventions for smoking cessation remain only moderately successful and pharmacological treatments (e.g., nicotine replacement therapies) are largely understudied among pregnant women (Forray 2016). High rates of maternal/perinatal smoking are also observed in younger (aged 20–24) women and those with less education, as well as those who identify as American Indian/Alaskan Native or live in rural communities (Ali et al. 2022; Azagba et al. 2020). Thus, additional research is needed to identify the specific needs of these groups to develop improved education, prevention, and treatment strategies.

The present results highlight the need for improved and easily accessed screening and treatment (Latuskie et al. 2019). This is particularly salient as legalization of cannabis and increased popularity of tobacco products (i.e., e-cigarettes) may change perceptions and increase use among pregnant women (Hawkins and Hacker 2022). Novel treatment interventions such as smartphone-based interventions, which have shown preliminary efficacy to reduce smoking among pregnant women (Kurti et al. 2022), may improve treatment and attenuate increasing use.

The present study demonstrated lower odds of past-month illicit prescription pain medication misuse in the third trimester compared the first trimester; however, this misuse (i.e., illicit/recreational use) remains significant, with approximately 10% of third trimester women, endorsing misuse of prescription pain medications within the past year. While this decrease (approximately 22% in first trimester) is positive, it highlights the problematic use of prescription opioids among pregnant women (Jones and Kraft 2019). Similar data from NSDUH 2005–2014 demonstrated that more than 5% of pregnant women reported past-year use of such medications (Kozhimannil et al. 2017). Given the numerous medical consequences of opioid use among mothers and neonates, this emphasizes the need to screen for illicit drugs and assess the misuse of prescription substances among pregnant women. Specifically, a recent study found that among drug- or self-harm-related maternal deaths in California, 74% of women made at least one visit to a local emergency department, and approximately 40% made three of more such visits (Goldman-Mellor and Margerison 2019). This offers a unique intervention point, when presenting to the local emergency department, to screen for perinatal substance use/misuse and refer women for treatment.

Overall, the present results highlight the need for continued screening and improved education and treatment for those continuing to use substances during pregnancy. Pregnant women are less likely than their non-pregnant counterparts to receive substance use treatment (Terplan et al. 2012). This may be due to the limited substance use interventions available (O’Connor and Whaley 2003). For example, opioid agonists have been shown to prevent relapse and improve substance use outcomes during pregnancy; however, these medications have high drop-out rates and this limits their effectiveness (Minozzi et al. 2013). In addition to the limited effective interventions for perinatal substance use, access to empirically supported interventions remain limited and legislation surrounding the criminalization of drug use during pregnancy has been shown to deter treatment seeking among pregnant women who use substances (Adams et al. 2021; Forray et al. 2015; Lester et al. 2004; Stone 2015; Tsuda-McCaie and Kotera 2022). This presents an urgent need for novel interventions and easily accessible treatment to improve the health outcomes of both mother and neonate, as well as conduct longitudinal research to examine drug use within pregnant women across all three trimesters.

Finally, given the lower likelihood of past-month drug use demonstrated in the second and third trimesters compared to the first trimester, there is a need to develop interventions to prevent postpartum relapse among those accessing care and achieving abstinence. A recent study demonstrated that 80% of women who had achieved abstinence during pregnancy relapsed postpartum (Forray et al. 2015). One promising line of research is the administration of progesterone following delivery to prevent relapse. A recent study demonstrated that abstinent, postpartum women smokers had a slower rate of relapse over a 3-month follow-up period when administered progesterone when compared to placebo (Forray et al. 2017). Exogenous progesterone administration has also shown promise among other illicit substances, including cocaine, so its utility as an intervention among postpartum women should be continued to be explored (Yonkers et al. 2014). Interventions designed to target postpartum psychosocial relapse factors, including stress, weight gain concerns, lack of social support, and postpartum depression, should continue to also be studied to address the high postpartum relapse rates reported in the literature (Chapman and Wu 2013; Hymowitz et al. 2003; Levine et al. 2016).

Treatment guidelines

It is strongly encouraged that providers utilize the Achieves of Women’s Mental Health (AWMH) and World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the management of alcohol use during pregnancy, which explicitly state that there is no safe level of alcohol use during pregnancy and screening of maternal alcohol use should be completed throughout pregnancy. Brief interventions are recommended for low to moderate alcohol consumption and hospitalization related to withdrawal symptoms is recommended for heavy/chronic alcohol use (Thibaut et al. 2019). Additionally, the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) guidelines for the management of illicit substance use during pregnancy include destigmatizing mental illness, providing accurate information to women, and implementing effective treatments; specifically, providers are encouraged to provide psychosocial and psychological treatments when appropriate and pharmacological interventions for moderate to severe disorders (Howard et al. 2017).

Limitations

The present study’s findings should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, a cross-sectional survey design was utilized in the NSDUH data collection. Thus, no causal inferences between pregnancy and substance use can be established. Additionally, the NSDUH is a survey-based measure, so the present study was limited to self-report data. This may be problematic as participants, especially pregnant women, may have underreported current substance use due to fear of subsequent consequences or stigma (Stone 2015). Additionally, due to the self-report nature of the survey, there was no assessment of substance use that coincided with the beginning of the current trimester; thus, it is difficult to assess past-month substance use that potentially overlapped trimesters or may overlap to a period of time in the first trimester when the women did not yet know she was pregnant. Finally, women in the first trimester may have been unaware of a positive pregnancy status at the time of the survey and were not included in the present results. Due to these concerns, the present study should be viewed as a conservative estimate of maternal substance use; however, results are consistent with those previously reported in the literature (e.g., Ebrahim and Gfroerer 2003; Forray et al. 2015; Massey et al. 2011; Tong et al. 2008).

Conclusion

Among pregnant women with past-year substance use, in the second and third trimesters, there are lower odds of past-month use of substances compared to the first trimester; however, some women struggle to abstain from substance use throughout their pregnancies. These findings are consistent with previous literature and provide further evidence that continued screening and intervention across trimesters is critical among pregnant women with a history of substance use. Utilizing the AWMH and WFSBP guidelines for the management of alcohol use during pregnancy and the WPA guidelines on management of illicit substance use during pregnancy is strongly encouraged. Continued efforts are needed to ameliorate barriers to substance use treatment among pregnant women and improve our current interventions for both prenatal substance use and postnatal relapse.

References

Adams ZM, Ginapp CM, Price CR, Qin Y, Madden LM, Yonkers K, Meyer JP (2021) “A good mother”: impact of motherhood identity on women’s substance use and engagement in treatment across the lifespan. J Subst Abuse Treat 130:108474

Addis A, Moretti ME, Ahmed Syed F, Einarson TR, Koren G (2001) Fetal effects of cocaine: an updated meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol 15(4):341–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-6238(01)00136-8

Ali MM, Nye E, West K (2022) Substance use disorder treatment, perceived need for treatment, and barriers to treatment among parenting women with substance use disorder in us rural counties. J Rural Health 38:70–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12488

Alshaarawy O, Anthony JC (2019) Cannabis use among women of reproductive age in the United States: 2002–2017. Addict Behav 99:106082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106082

Azagba S, Manzione L, Shan L, King J (2020) Trends in smoking during pregnancy by socioeconomic characteristics in the United States, 2010–2017. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2748-y

Berenson AB, Wilkinson GS, Lopez LA (1995) Substance use during pregnancy and peripartum complications in a triethnic population. Int J Addict 30(2):135–145

Best D, Segal J, Day E (2009) Changing patterns of heroin and crack use during pregnancy and beyond. J Subst Use 14(2):124–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890802658962

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019) Pregnancy-related deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-relatedmortality.htm

Chapman SLC, Wu L-T (2013) Postpartum substance use and depressive symptoms: a review. Women Health 53(5):479–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2013.804025

Coleman-Cowger VH, Schauer GL, Peters EN (2017) Marijuana and tobacco co-use among a nationally representative sample of US pregnant and non-pregnant women: 2005–2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health findings. Drug Alcohol Depend 177:130–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.025

Ebrahim SH, Gfroerer J (2003) Pregnancy-related substance use in the United States during 1996–1998. Obstet Gynecol 101(2):347–349

Forray A (2016) Substance use during pregnancy. F1000Research, 5, F1000 Faculty Rev-1887. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7645.1

Forray A, Gilstad-Hayden K, Suppies C, Bogen D, Sofuoglu M, Yonkers KA (2017) Progesterone for smoking relapse prevention following delivery: a pilot, randomized, double-blind study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 86:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.09.012

Forray A, Merry B, Lin H, Ruger JP, Yonkers KA (2015) Perinatal substance use: a prospective evaluation of abstinence and relapse. Drug Alcohol Depend 150:147–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.027

Goldman-Mellor S, Margerison CE (2019) Maternal drug-related death and suicide are leading causes of postpartum death in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol 221(5):489.e1-489.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.05.045

Gorman MC, Orme KS, Nguyen NT, Kent EJ, Caughey AB (2014) Outcomes in pregnancies complicated by methamphetamine use. Am J Obstet Gynecol 211(4):429.e421-429.e427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.005

Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, … Hasin DS (2017) Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiat, 74(9):911–923. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161

Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, . . . Hasin DS (2016) Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. JAMA Psychiat, 73(1), 39-47. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132

Hawkins SS, Hacker MR (2022) Trends in use of conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and marijuana in pregnancy and impact of health policy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 65(2):305–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000690

Howard LM, Chandra P, Hanlon C, Fisher J, Gregoire A, Herrman H, Honikman, Simone S, Kulkarni J, Milgrom J, Rahman A, Rondon MB, Wisner K (2017) Perinatal mental health: position statement. World Psychiatric Assoc

Hudak ML, Tan RC (2012) Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics 129(2):e540–e560. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3212

Hymowitz N, Schwab M, McNerney C, Schwab J, Eckholdt H, Haddock K (2003) Postpartum relapse to cigarette smoking in inner city women. J Natl 95(6):461–474

Jones HE, Kraft WK (2019) Analgesia, opioids, and other drug use during pregnancy and neonatal abstinence syndrome. Clin Perinatol 46(2):349–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2019.02.013

Kozhimannil KB, Graves AJ, Levy R, Patrick SW (2017) Nonmedical use of prescription opioids among pregnant U.S. women. Women’s Health Issues 27(3):308–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2017.03.001

Kurti AN, Nighbor TD, Tang K, Bolívar HA, Evemy CG, Skelly J, Higgins ST (2022) Effect of smartphone-based financial incentives on peripartum smoking among pregnant individuals: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 5(5):e2211889–e2211889

Latuskie KA, Leibson T, Andrews NCZ, Motz M, Pepler DJ, Shinya I (2019) Substance use in pregnancy among vulnerable women seeking addiction and parenting support. Int J Ment Health Addiction 17:137–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0005-7

Lester BM, Andreozzi L, Appiah L (2004) Substance use during pregnancy: time for policy to catch up with research. Harm Reduct J 1:5–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-1-5

Levine MD, Cheng Y, Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA, Emery RL (2016) Preventing postpartum smoking relapse: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 176(4):443–452. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0248

MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C (2016) Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol 128(3):447–455. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001556

Mangla K, Hoffman MC, Trumpff C, O’Grady S, Monk C (2019) Maternal self-harm deaths: an unrecognized and preventable outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 221(4):295–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.056

Massey SH, Lieberman DZ, Reiss D, Leve LD, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM (2011) Association of clinical characteristics and cessation of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy. Am J Addict 20(2):143–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00110.x

McHugh RK, Wigderson S, Greenfield SF (2014) Epidemiology of substance use in reproductive-age women. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 41(2):177–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2014.02.001

Minozzi S, Amato L, Bellisario C, Ferri M, Davoli M (2013) Maintenance agonist treatments for opiate-dependent pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006318.pub3

Moore DG, Turner JD, Parrott AC, Goodwin JE, Fulton SE, Min MO, . . . Singer LT (2010) During pregnancy, recreational drug-using women stop taking ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine) and reduce alcohol consumption, but continue to smoke tobacco and cannabis: initial findings from the development and infancy study. J Psychopharmacol 24(9), 1403-1410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109348165

O’Connor MJ, Whaley SE (2003) Alcohol use in pregnant low-income women. J Stud Alcohol 64(6):773–783. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2003.64.773

Oh S, Reingle Gonzalez JM, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, DiNitto DM (2017) Prevalence and correlates of alcohol and tobacco use among pregnant women in the United States: evidence from the NSDUH 2005–2014. Prev Med 97:93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.01.006

Pineles BL, Park E, Samet JM (2014) Systematic review and meta-analysis of miscarriage and maternal exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol 179(7):807–823. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt334

Qato DM, Zhang C, Gandhi AB, Simoni-Wastila L, Coleman-Cowger VH (2020) Co-use of alcohol, tobacco, and licit and illicit controlled substances among pregnant and non-pregnant women in the United States: findings from 2006 to 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data. Drug Alcohol Depend 206:107729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107729

Salihu HM, Wilson RE (2007) Epidemiology of prenatal smoking and perinatal outcomes. Early Hum Dev 83(11):713–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.08.002

Singh GK (2021) Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969–2018. Int J MCH AIDS 10(1):29–42. https://doi.org/10.21106/ijma.444

Shmulewitz D, Hasin DS (2019) Risk factors for alcohol use among pregnant women, ages 15–44, in the United States, 2002 to 2017. Prev Med 124:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.027

Soneji S, Beltrán-Sánchez H (2019) Association of maternal cigarette smoking and smoking cessation with preterm birth. JAMA Netw Open 2(4):e192514. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2514

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMSHA]. (2015). Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMSHA]. (2016, 01/14/2016). About Popuatlion Data/ NSDUH. Retrieved 01/22, 2017

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMSHA]. (2018). 2015 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH PUBLIC USE FILE CODEBOOK. 2021, from https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/field-uploads-protected/studies/NSDUH-2015/NSDUH-2015-datasets/NSDUH-2015-DS0001/NSDUH-2015-DS0001-info/NSDUH-2015-DS0001-info-codebook.pdf

Sokol RJ, Delaney-Black V, Nordstrom B (2003) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. JAMA 290(22):2996–2999. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.22.2996

Stone R (2015) Pregnant women and substance use: fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health & Justice 3(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-015-0015-5

Terplan M, McNamara EJ, Chisolm MS (2012) Pregnant and non-pregnant women with substance use disorders: the gap between treatment need and receipt. J Addict Dis 31(4):342–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2012.735566

Thibaut F, Chagraoui A, Buckley L, Gressier F, Labad J, Lamy S, Potenza MN, Rondon M, Riecher-Rössler A, Soyka M, Yonkers K (2019) WFSBP and IAWMH Guidelines for the treatment of alcohol use disorders in pregnant women. World J Biol Psychiatry 20(1):17–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2018.1510185

Tong VT, Dietz PM, Farr SL, D’Angelo DV, England LJ (2013) Estimates of smoking before and during pregnancy, and smoking cessation during pregnancy: comparing two population-based data sources. Public Health Rep 128(3):179–188

Tong VT, England LJ, Dietz PM, Asare LA (2008) Smoking patterns and use of cessation interventions during pregnancy. Am J Prev Med 35(4):327–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.033

Trost SL, Beauregard JL, Smoots AN, Ko JY, Haight SC, Moore Simas TA, . . . Goodman D (2021) Preventing pregnancy-related mental health deaths: insights from 14 US maternal mortality review committees, 2008–17. Health Aff., 40(10), 1551-1559. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00615

Tsuda-McCaie F, Kotera Y (2022) A qualitative meta-synthesis of pregnant women’s experiences of accessing and receiving treatment for opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Rev 41:851–862. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13421

Wang GS, Buttorff C, Wilks A, Schwam D, Metz TD, Tung G, Pacula RL (2022) Cannabis legalization and cannabis-involved pregnancy hospitalizations in Colorado. Prev Med 156:106993

Yonkers KA, Forray A, Nich C, Carroll KM, Hine C, Merry BC, . . . Sofuoglu M (2014) Progesterone for the reduction of cocaine use in post-partum women with a cocaine use disorder: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study. Lancet Psychiat 1(5), 360-367. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70333-5

Young-Wolff KC, Tucker L, Alexeeff S et al (2017) Trends in self-reported and biochemically tested marijuana use among pregnant females in California from 2009–2016. JAMA 318(24):2490–2491. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.17225

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants U54AA027989 (SAM), P50DA033945 (SAM), K01AA025670 (TLV), R03AA028361 (TLV), K23AA02689 (WR), and T32DA007238 (MRP). The funding agency had no involvement in the study design, interpretation of data, writing of the report or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by MacKenzie Peltier, PhD, and Walter Roberts, PhD. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MacKenzie Peltier, PhD, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This is an observational study, which utilizes publicly available, de-identified data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peltier, M.R., Roberts, W., Verplaetse, T.L. et al. Licit and illicit drug use across trimesters in pregnant women endorsing past-year substance use: Results from National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2009–2019). Arch Womens Ment Health 25, 819–827 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01244-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01244-6