Abstract

Pregnant women are at high risk of mood and anxiety disorders, and options for non-pharmacological treatment are limited. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) has strong evidence among people with mood and anxiety disorders, but limited studies reported the effectiveness of MBCT on perinatal comorbid conditions. This study aimed to examine the effects of an 8-week MBCT intervention on pregnant women with comorbid depression and anxiety. In this randomized controlled study, 38 pregnant women with a diagnosis of depression and varying levels of comorbid anxiety disorders were randomly assigned to either MBCT or a control group. Scores on the Beck Depression Inventory-II, Beck Anxiety Inventory, Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, and Scales of Psychological Wellbeing were used as outcome measures at baseline, after MBCT, and through 1-month follow-up. Intent to treat analyses provided preliminary evidence that MBCT can be effective in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms and in enhancing the use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies and psychological well-being. Improvements in outcomes were maintained 1 month. Results provide cross-cultural support for MBCT as a treatment for depression and anxiety in pregnant women. This brief and non-pharmacological treatment can be used to improve maternal psychological health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite common perceptions of the perinatal period as a time of joy and psychological well-being, pregnancy does not protect against psychiatric disorders, as mental health issues may emerge or worsen during the pregnancy (Prady et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2018). Specifically, some women are more vulnerable to a wide range of psychological disorders during the pregnancy (Novick and Flynn 2013), with mood and anxiety disorders among the most common mental health diagnoses (Fairbrother et al. 2015). Evidence suggests that up to 20% of women are affected by depression and anxiety during pregnancy (Dhillon et al. 2017; Dimidjian and Goodman 2009; Fairbrother et al. 2015).

From a treatment perspective, perinatal depression and anxiety may be under-detected and untreated. Prospective studies indicate that when perinatal depression and anxiety are left untreated, they have a variety of important health outcomes for mothers and infants (Madigan et al. 2018; Schetter and Tanner 2012). These problems can represent a significant burden for mothers in terms of reducing psychological well-being, quality of life, and overall health (Brummelte 2018; Lancaster et al. 2010). Therefore, development and validation of effective treatment programs during pregnancy are important and crucial (Lin et al. 2018; Prady et al. 2018).

Psychotropic medications such as antidepressants and benzodiazepines are often used to manage depression and anxiety during pregnancy (Yonkers et al. 2014); however, because of potential risks of fetal exposure to psychotropic medications, the majority of pregnant women overwhelmingly prefer non-pharmacological treatments during pregnancy (Goodman et al. 2011). So, effective and evidence-based non-pharmacologic approaches are urgently needed in this context (Udechuku et al. 2010). It is evident that there is a need for innovation in developing and expanding feasible, acceptable, and efficacious non-pharmacologic treatment approaches to address perinatal depression and anxiety at all levels of symptom severity (Bonacquisti et al. 2017).

Mindfulness-based interventions make them particularly good candidates for intervention during pregnancy (Vieten and Astin 2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) may have high applicability for at-risk pregnant women (Dhillon et al. 2017; Shi and MacBeth 2017), and recent studies provide support for the benefits of this treatment approach for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (Dimidjian et al. 2015, 2016; Luberto et al. 2018; Shallcross et al. 2018; Shulman et al. 2018). It specifically targets the most robust risk factors and depressive cognitive styles among pregnant women (Dimidjian et al. 2016; Pearson et al. 2013), and maternal anxious thoughts such as intrusive thoughts of harm to baby, fears of childbirth, concerning delivery or malformations of child (Loughnan et al. 2018; Ross and McLean 2006).

MBCT has garnered considerable support for the efficacious treatment of depression relapse (Segal et al. 2018) and is beginning to garner support to treat acute depression along with many other forms of psychopathology (Shapero et al. 2019). Mindfulness also has been linked to the positive outcomes regarding one’s mental health such as increased emotion regulation capacities, and psychological well-being (Arch and Craske 2006; Stevenson et al. 2018). Mindfulness increases willingness to tolerate and handle uncomfortable emotions (Hayes et al. 2011). Participants develop body awareness, self-regulation, and emotion regulation skills through repeated meditation practices in MBCT (Grabovac et al. 2011; Shapero et al. 2019). Additionally, it is important to note that mindfulness-based interventions do not target symptom reduction as a goal, but rather, their primary aim is to increase people’s psychological well-being (Brown and Ryan 2003; Dunn et al. 2012). As Dimidjian et al. (2016) noted, the goal of perinatal MBCT is to enhance psychological well-being in the context of pregnancy and motherhood.

To our knowledge, limited randomized controlled trials have been conducted evaluating the effectiveness of MBCT on perinatal depressive and anxiety disorders in various cultures. Thus, further research and randomized control trials on this method are needed (Dimidjian et al. 2016). Given the high prevalence of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders during pregnancy (Dhillon et al. 2017) and significant cost associated with delayed treatment (Madigan et al. 2018), and also given the importance of having empirically validated treatments available in different cultures, we conducted the current study to assess the effectiveness of MBCT for pregnant women in Iranian population. The main aim of this study was to extend the effectiveness of the MBCT in order to contribute to the dissemination of evidence-based approaches for the treatment of depression and anxiety in pregnant women. It was hypothesized that participation in this intervention would reduce depressive and anxious disorders, modify emotion regulation strategies, and would increase psychological well-being during pregnancy. The results of present study provide cross-cultural support for MBCT as a treatment for mood and anxiety disorders during pregnancy.

Method

Procedure

The method was based on a randomized controlled trial design using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines (Schulz et al. 2010). The study included a pre-test, post-test, and a 1-month follow-up session. Women were recruited from eight medical and obstetric services in Qorveh city, Kurdistan province, Iran. Study information was provided to mental health clinicians, gynecologists, and midwives, and they were encouraged to refer potentially eligible women. Pregnant women who were within 1 to 6 months of gestational age were asked if they were interested in participating in a study focused on improving mood and anxiety. Following informed consent procedures, the full structured clinical interview for DSM-5 (First and Williams 2016) was administered by a trained master’s level clinical psychologist as the primary clinical diagnostic instrument. Following eligibility assessment, participants provided demographic and other background information and completed a series of standardized questionnaires aimed at evaluating levels of depression, anxiety, emotion regulation, and psychological well-being.

Primary inclusion criteria included pregnant women (1) within 1 to 6 months of gestational age, (2) meeting DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) criteria for depression and anxiety disorders, (3) to have a score at least in the moderate range on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II total score > 20) and on the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI total score > 22), and (4) aged 18 years or older. Participants were excluded if they met diagnostic criteria for other DSM-5 psychiatric disorders, including current psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, substance abuse or dependence, personality disorders, taking psychotropic drugs, and risk pregnancies.

Two hundred and sixty-three patients met inclusion criteria, and among these, 38 accepted to take part in the study. Participants who agreed to participate were randomly assigned to either an MBCT group (n = 19) or control group (n = 19). Randomization was conducted by an independent assessor who had no involvement in recruitment or in post-treatment assessments, using a computer-generated blocks of random numbers. When groups were evenly balanced, pre-prepared blocked randomization lists were used to allocate participants to either MBCT or control. The MBCT group received eight sessions of MBCT while the control group did not receive any intervention. In order to comply with ethical principles, after 1-month follow-up, two psychoeducational sessions about depression and anxiety and its effects on mother and the fetus development were conducted for the control group.

Participants

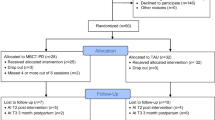

The CONSORT diagram (Fig. 1) summarizes the process of recruitment and flow of participants through the study to the primary follow-up point. Table 1 illustrates participant baseline socio-demographic features and clinical characteristics. The majority of participants (53.8%) were ranged in age from 26 to 30 years (Mage = 28.63, SD = 3.02). Approximately 61.50% participants reported being unemployed, 27.47% had a high school diploma, and 57.89% a university education, 79.36% was urban, 68.42% had low socioeconomic status, and 31.57% of them had the first pregnancy experience. Approximately 47.36% of them met full diagnostic criteria for current or life time major depression disorder, and 42.10% had also comorbid anxiety disorder (including GAD, social phobia, or post-traumatic stress disorder).

Treatment

The MBCT group participants received eight weekly 2-h group sessions. Treatment rationale, model, objectives, and themes were according to the standard MBCT treatment manual (Segal et al. 2018) with modifications for the perinatal period. Modifications for perinatal depression and anxiety were based on clinical trials in this fields (Dimidjian et al. 2016; Goodman et al. 2014; Luberto et al. 2018) and included stronger emphasis on brief formal and informal mindfulness and meditation practices customized for the perinatal period. Formal practices included the body scan, mindful yoga, and sitting meditation. Informal mindfulness practices included mindfulness of everyday activities such as mindful eating and mindful walking. Each session had a central theme and included didactic presentations, group exercises aimed at cognitive skill development, formal meditation practices, and leader-facilitated group inquiry and discussion. The overarching theme of momentary awareness and acceptance of negative emotions and affect during pregnancy (e.g., depression, anxiety, rumination, worry) was introduced and reinforced in complementary ways throughout the training. Approximately 30 min of daily home practice of formal and informal mindfulness practices was assigned and encouraged between classes. Audio-recorded files were provided each week to guide mindfulness meditation practices at home. In addition, for five of the weeks, participants were encouraged to also practice the 3-min breathing space three times per day. During the last 3 weeks of the intervention, they were encouraged to also utilize the 3-min breathing space ‘whenever they noticed unpleasant thoughts or feelings’.

Sessions were run by a trained master’s level clinical psychologist who had at least 2 years of clinical experience and received supervised training in delivering MBCT for mood and anxiety disorders. All sessions were audiotaped and were reviewed weekly by a supervisor to establish internal validity. At the end of each session, the supervisor and the therapist discussed the contents of the sessions to ensure adherence to MBCT. The adherence of intervention was under the supervision of one doctoral-level clinical psychologists (MZ) with varying lengths of post-qualification experience and extensive experience in the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders.

Measures

Beck Depression Inventory-II

The BDI-II (Beck et al. 1996) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure the level of severity of disorders of depression. Items are scored from 0 to 3; higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. The BDI-II has high internal consistency (α = 0.93) and test-retest reliability for a 1-week interval (0.93) (Beck et al. 1996). Cronbach’s α in the present study was 0.82.

Beck Anxiety Inventory

The BAI (Beck et al. 1988) is a 21-item self-report measure designed to reflect the severity of somatic and cognitive symptoms of anxiety over the previous week. Items are scored on a 4-point scale (0–3) with a total score ranging from 0 to 63. Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.79.

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

The ERQ (Gross and John 2003) is a 10-item self-report measure designed to assess individual differences in the habitual use of two emotion regulation strategies: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Items are scored on a 7-point scale (1–7). In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.78 for the cognitive reappraisal subscale and 0.81 for the expressive suppression subscale.

Scales of Psychological Well-being

The SPWB (Ryff 1989) is a 42-item scale that assesses six dimensions of psychological well-being: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. This 42-item measure has been used as a reliable measure of well-being with high internal consistencies (Stevenson et al. 2018). In the current study, Cronbach’s α coefficients for all of the six dimensions were as follows: autonomy, 0.77; environmental mastery, 0.68; personal growth, 0.91; positive relations; 0.84; purpose in life, 0.81; and self-acceptance, 0.77.

Data analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23 (IBM). Independent sample t tests and Chi-square tests were conducted to examine baseline differences between the two groups. To compare the effects of MBCT and control group on the outcome measures (i.e., BDI, BAI, ER, SPWB), a series of 3 (time: baseline, post-treatment, follow-up) × 2 (group: MBCT vs. control) mixed method repeated measure (MMRM) were conducted. MMRM analysis allows for analysis of the full intent-to-treat sample and all available data points as any missing data points are modeled and included in the analysis. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses were conducted with the use of SPSS Missing Value Analysis to impute all missing data on the continuous measures with the expectation-maximization method. This method computes missing values based on maximum likelihood estimates using observed data in an iterative process.

Results

Demographic data were analyzed employing Chi-square and independent two-sample Student’s t tests. Independent sample t test and Chi-square analysis showed no significant pretreatment differences (ps > .05) between two groups for any baseline socio-demographic feature or clinical characteristic, indicating homogeneity between groups. See Table 1 for detailed demographic comparison results. The means and standard deviations in BDI-II, BAI, ERQ, and SPWB at baseline, post-treatment, and follow-up are illustrated in Table 2.

Results from the MMRM indicate greater improvements in levels of depression and anxiety in the MBCT groups than in the control group. As to BDI-II, results from the ITT analysis indicated a significant effect of time, F = (39.53), p < .0001, ηp2 = .60; and a significant time × group interaction, F = (55.06), p < .0001, ηp2 = .68. Post hoc comparisons showed that the MBCT group had a significant decrease in BDI-II scores from baseline to post-treatmenti and BDI-II scores remained significantly lower than those of the control group at follow-up (ps < .0001) (Table 3).

As to BAI, results from the ITT analysis indicated a significant effect of time, F = (43.72), p < .0001, ηp2 = .62; and a significant time × group interaction, F = (52.68), p < .0001, ηp2 = .67. Post hoc comparisons showed that the MBCT group had a significant decrease in BAI scores from baseline to post-treatment and BAI scores remained significantly lower than those of the control group at follow-up (ps < .0001).

Results from the ITT analysis also indicated that the MBCT group had stronger effects in improving emotion regulation strategies both at post-treatment and follow-up than the wait-list group. For cognitive reappraisal subscale, a significant effect of time, F = (7.61), p = .003, ηp2 = .22; and a significant time × group interaction, F = (9.27), p = .001, ηp2 = .26, emerged. Post hoc analyses showed that the MBCT group had significant increases in levels of cognitive reappraisal from baseline to post-treatment, and scores remained significantly higher compared to the control group at follow-up (ps < .0001). For expressive suppression subscale, a significant effect of time, F = (8.31), p = .001, ηp2 = .24; and a significant time × group interaction, F = (5.85), p < .008, ηp2 = .18, emerged. Post hoc analyses showed that the MBCT group had a significant decrease in levels of expressive suppression from baseline to post-treatment, and scores remained significantly lower than those of the control group at follow-up (ps < .0001).

As to SPWB, results from the ITT analysis indicated a significant effect of time, F = (94.09), p < .0001, ηp2 = .78; and a significant time × group interaction, F = (91.39), p < .0001, ηp2 = .77. Post hoc comparisons showed that the MBCT group had a significant decrease in SPWB scores from baseline to post-treatment and SPWB scores remained significantly lower than those of the control group at follow-up (ps < .0001).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of MBCT intervention for pregnant women with comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders. We found that MBCT reduces the depressive and anxiety symptoms comparing with the control group. The results of time effect indicate that MBCT had a large, significant impact on reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms from pre-to posttreatment that continued through follow-up. Consistent with our results, previous findings showed the effectiveness of MBCT in the treatment of depression and anxiety in pregnant women (Dimidjian et al. 2015; Krusche et al. 2018; Loughnan et al. 2018; Luberto et al. 2018; Shulman et al. 2018; Taylor et al. 2016).

Previous studies suggest that individuals with depression and anxiety are particularly vulnerable to negative cognitive style that trigger the onset or relapse of depressive and anxiety disorders and prolong the duration of these disorders (Alloy et al. 2006; Shapero et al. 2017; Zemestani et al. 2017). Stressful life events (e.g., pregnancy) activate these negative cognitive styles, which include perseverative negative thinking patterns such as depressive rumination, worry, and self-criticism; if persistent, these may escalate to depressive or anxiety onset or relapse (Shapero et al. 2019). The theoretical model on which MBCT is based emphasizes identifying these thought patterns as they arise and viewing them as temporary mental phenomena rather than as facts or realities to identify with or react to (a process referred to as “meta-awareness,” sometimes used interchangeably with “decentering” (Segal et al. 2018; van der Velden et al. 2015)

MBCT for perinatal depression and anxiety focuses on training pregnant women to develop a different relationship with their thoughts by developing the skill to notice one’s thinking patterns and then practicing different strategies to distance oneself from these thoughts. Taken together, based on the theoretical underpinnings of MBCT, reductions in severity of depression and anxiety in pregnant women may be explained by increases in meta-awareness, self-transcendence, coupled with encouraging acceptance, and non-reactivity to the negative thoughts and emotions.

Regarding emotion regulation, we found that MBCT increases the cognitive reappraisal and decreases expressive suppression strategies compared to control group. The results of time effect indicate that MBCT had a small, yet significant impact on modifying adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies from pre-to posttreatment that continued through follow-up. This findings are consistent with previous research on the effectiveness of mindfulness on emotion regulation (Arch and Craske 2006; Goldin and Gross 2010; Hölzel et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2008). The results may explain by the fact that women who learn mindfulness during pregnancy are likely to use those skills to manage stressful aspects of pregnancy, resulting in better regulating emotions. It seems that nonjudgmental stance conveyed in MBCT teaches pregnant women to handle their emotions in a more rational way with less emotional suppression. These elevated emotion regulation skills through MBCT led to decrease in depressive and anxiety symptoms and to increase in psychological well-being (Shapero et al. 2019; Zemestani and Ottaviani 2016). Recent research suggests that there is a cultural difference in regulating emotions, especially in expressive suppression (Sun and Lau 2018). Eastern cultures mainly emphasize the suppression of emotions in women and suppression could consider as an advantage for these women (Ghorbani et al. 2013). Therefore, in therapeutic interventions in these cultures, we may find significant reduction in the depressive and anxiety symptoms and not find more reduction in suppression of emotions (Zemestani et al. 2017). The intersection between culture, suppression of emotions, and paradoxical treatment outcomes could be a fruitful area for future research.

Regarding psychological well-being, we found that MBCT increases the SPWB scores compared to control group. The results of time effect indicate that MBCT had a large, significant impact on psychological well-being from pre-to posttreatment that continued through follow-up. These outcomes are consistent with previous studies (Dunn et al. 2012) that suggested acting with self-acceptance and non-judging aspects of mindfulness could be predictive of psychological well-being in pregnant women. Mindfulness serves as an important mechanism in allowing individuals to disengage from automatic thoughts and unhealthy copping patterns, while simultaneously promoting informed and self-endorsed emotion regulation, which is associated with the enhancement of well-being outcomes including lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (Stevenson et al. 2018).

This study has a number of limitations that should be noted. First, the relatively small number of participants per group and missing data in the follow-up resulted in limited power to demonstrate consistently significant findings. Future work with larger samples to provide a more robust test of the effectiveness of MBCT in pregnant women is needed. Second, our sample included women with different gestational age, thereby limiting generalizability. It is important for future research to examine the extent to which these findings can be generalized to women who are in similar gestational age. Third, our outcome measures were limited to self-reported levels of depression, anxiety, emotion regulation, and psychological well-being, highlighting the need for a more comprehensive assessment. Fourth, our follow-up was relatively short and may have been insufficient to detect long-term treatment gains. It will be important for future studies to investigate the long-term effects of MBCT. Repeated measurements of follow-up at 6 and 12 months would be useful. Lastly, the current study compared MBCT to a control group; it did not provide a test of whether MBCT differed from other empirically validated active treatments. Future studies should utilize more active control groups including other viable treatments from a variety of theoretical orientations.

Despite these limitations, findings are particularly encouraging and support the applicability and effectiveness of MBCT in other cultures. Results add to the literature and provide cross-cultural support for the effectiveness of MBCT in treating comorbid depression and anxiety during pregnancy.

References

Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Panzarella C, Rose DT (2006) Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. J Abnorm Psychol 115(1):145–156

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author, Washington, DC

Arch JJ, Craske MG (2006) Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behav Res Ther 44(12):1849–1858

Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA (1988) An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 5(6):893–897

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK (1996) Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio 78(2):490–498

Bonacquisti A, Cohen MJ, Schiller CE (2017) Acceptance and commitment therapy for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders: development of an inpatient group intervention. Arch Women's Ment Health 20(5):645–654

Brown KW, Ryan RM (2003) The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(4):822–848

Brummelte S (2018) Treating maternal depression: considerations for the well-being of the mother and child. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci 5(1):110–117

Dhillon A, Sparkes E, Duarte RV (2017) Mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness 8(6):1421–1437

Dimidjian S, Goodman S (2009) Nonpharmacological intervention and prevention strategies for depression during pregnancy and the postpartum. Clin Obstet Gynecol 52(3):498–515

Dimidjian S, Goodman SH, Felder JN, Gallop R, Brown AP, Beck A (2015) An open trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of perinatal depressive relapse/recurrence. Arch Women's Ment Health 18(1):85–94

Dimidjian S, Goodman SH, Felder JN, Gallop R, Brown AP, Beck A (2016) Staying well during pregnancy and the postpartum: a pilot randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol 84(2):134–145

Dunn C, Hanieh E, Roberts R, Powrie R (2012) Mindful pregnancy and childbirth: effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on women’s psychological distress and well-being in the perinatal period. Arch Women's Ment Health 15(2):139–143

Fairbrother N, Young AH, Janssen P, Antony MM, Tucker E (2015) Depression and anxiety during the perinatal period. BMC psychiatry 15(1):206

First MB, Williams JB (2016) SCID-5-CV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders: Clinician Version. American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Philadelphia

Ghorbani N, Watson P, Salimian M, Chen Z (2013) Shame and guilt: relationships of test of self-conscious affect measures with psychological adjustment and gender differences in Iran. Interpersona: Int J Pers Relat 7(1):97–109

Goldin PR, Gross JJ (2010) Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion 10(1):83–91

Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D (2011) Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(1):1–27

Goodman JH, Guarino A, Chenausky K, Klein L, Prager J, Petersen R, Forget A, Freeman M (2014) CALM pregnancy: results of a pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal anxiety. Arch Women's Ment Health 17(5):373–387

Grabovac AD, Lau MA, Willett BR (2011) Mechanisms of mindfulness: a Buddhist psychological model. Mindfulness 2(3):154–166

Gross JJ, John OP (2003) Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 85(2):348–362

Hayes CS, Strosahl DK, Wilson GK (2011) Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change. Guilford Press, New York City

Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U (2011) How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci 6(6):537–559

Krusche A, Dymond M, Murphy SE, Crane C (2018) Mindfulness for pregnancy: a randomised controlled study of online mindfulness during pregnancy. Midwifery 65:51–57

Kumar S, Feldman G, Hayes A (2008) Changes in mindfulness and emotion regulation in an exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression. Cogn Ther Res 32(6):734–744

Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM, Davis MM (2010) Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202(1):5–14

Lin P-Z, Xue J-M, Yang B, Li M, Cao F-L (2018) Effectiveness of self-help psychological interventions for treating and preventing postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Arch women's Ment Health 21(5):491–503

Loughnan SA, Wallace M, Joubert AE, Haskelberg H, Andrews G, Newby JM (2018) A systematic review of psychological treatments for clinical anxiety during the perinatal period. Arch Women's Ment Health 21(5):481–490

Luberto CM, Park ER, Goodman JH (2018) Postpartum outcomes and formal mindfulness practice in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal women. Mindfulness 9(3):850–859

Madigan S, Oatley H, Racine N, Fearon RP, Schumacher L, Akbari E, Cooke J, Tarabulsy GM, Tarabulsy GM (2018) A meta-analysis of maternal prenatal depression and anxiety on child socio-emotional development. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 57(9):645–657

Novick D, Flynn H (2013) Psychiatric symptoms and pregnancy. Women’s health psychology. Wiley, New York

Pearson RM, Evans J, Kounali D, Lewis G, Heron J, Ramchandani PG, O'Conner TG, Stein A (2013) Maternal depression during pregnancy and the postnatal period: risks and possible mechanisms for offspring depression at age 18 years. JAMA Psychiatry 70(12):1312–1319

Prady SL, Hanlon I, Fraser LK, Mikocka-Walus A (2018) A systematic review of maternal antidepressant use in pregnancy and short-and long-term offspring’s outcomes. Arch Women's Ment Health 21(2):127–140

Ross LE, McLean LM (2006) Anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry 67(8):1285–1298

Ryff CD (1989) Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 57(6):1069–1083

Schetter CD, Tanner L (2012) Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Curr Opin Psychiatry 25(2):141–148

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D (2010) CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med 8(1):18

Segal Z, Williams M, Teasdale J (2018) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. Guilford Publications, New York City

Shallcross AJ, Willroth EC, Fisher A, Dimidjian S, Gross JJ, Visvanathan PD, Mauss IB (2018) Relapse/recurrence prevention in major depressive disorder: 26-month follow-up of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus an active control. Behav Ther 49(5):836–849

Shapero BG, McClung G, Bangasser DA, Abramson LY, Alloy AB (2017) Interaction of biological stress recovery and cognitive vulnerability for depression in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 46(1):91–103

Shapero BG, Greenberg J, Pedrelli P, Desbordes G, Lazar SW (2019) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. In: The Massachusetts General Hospital Guide to Depression. Springer, Berlin, pp 167–177

Shi Z, MacBeth A (2017) The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on maternal perinatal mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Mindfulness 8(4):823–847

Shulman B, Dueck R, Ryan D, Breau G, Sadowski I, Misri S (2018) Feasibility of a mindfulness-based cognitive therapy group intervention as an adjunctive treatment for postpartum depression and anxiety. J Affect Disord 235:61–67

Smith CA, Shewamene Z, Galbally M, Schmied V, Dahlen H (2018) The effect of complementary medicines and therapies on maternal anxiety and depression in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 245(15):428–439

Stevenson JC, Millings A, Emerson L-M (2018) Psychological well-being and coping: the predictive value of adult attachment, dispositional mindfulness, and emotion regulation. Mindfulness 10(2):256–271

Sun M, Lau AS (2018) Exploring cultural differences in expressive suppression and emotion recognition. J Cross-Cult Psychol 49(4):664–672

Taylor BL, Cavanagh K, Strauss C (2016) The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in the perinatal period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 11(5):e0155720

Udechuku A, Nguyen T, Hill R, Szego K (2010) Antidepressants in pregnancy: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 44(11):978–996

van der Velden AM, Kuyken W, Wattar U, Crane C, Pallesen KJ, Dahlgaard J, Fjorback LO, Piet J (2015) A systematic review of mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in the treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 37:26–39

Vieten C, Astin J (2008) Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention during pregnancy on prenatal stress and mood: results of a pilot study. Arch Women's Ment Health 11(1):67–74

Yonkers KA, Blackwell KA, Glover J, Forray A (2014) Antidepressant use in pregnant and postpartum women. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 10(1):369–392

Zemestani M, Ottaviani C (2016) Effectiveness of mindfulness-based relapse prevention for co-occurring substance use and depression disorders. Mindfulness 7(6):1347–1355

Zemestani M, Imani M, Ottaviani C (2017) A preliminary investigation on the effectiveness of unified and Transdiagnostic cognitive behavior therapy for patients with comorbid depression and anxiety. Int J Cogn Ther 10(2):175–185

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in these studies were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All study procedure was approved by the Kurdistan University ethic review board.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zemestani, M., Fazeli Nikoo, Z. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for comorbid depression and anxiety in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Womens Ment Health 23, 207–214 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-019-00962-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-019-00962-8