Abstract

Background

The treatment for multiple sclerosis-related trigeminal neuralgia (MS-TN) is less efficacious and associated with higher recurrence rates than classical TN. No consensus has been reached in the literature on the choice procedure for MS-TN patients. The aim of this study was to assess the incidence and surgical outcomes of medically refractory MS-TN.

Methods

Patient records were retrospectively reviewed for all Manitobans undergoing first procedure for medically refractory MS-TN between 2000 and 2014. Subsequent procedures were then recorded and analyzed in this subgroup of patients. The primary outcome measure was time to treatment failure.

Results

The incidence of medically refractory MS-TN was 1.2/million/year. Twenty-one patients with 26 surgically treated sides underwent first rhizotomy including 13 GammaKnife and 13 percutaneous rhizotomies comprised of ten glycerol injections and three balloon compressions. Subsequent procedures were required on 23 sides (88%), including 24 GammaKnife, 19 glycerol injections, 25 balloon compressions, two microvascular decompressions, and four open partial surgical rhizotomies with a total of 99 surgeries on 26 sides (range, 1–12 each).

Conclusions

The majority of MS-TN patients become medically refractory and require multiple repeat surgical procedures. MS-TN procedures were associated with high rates of pain recurrence and our data suggests reoperation within 1 year is often necessary. Optimal management strategy in this patient population remains to be determined. Patients need to be counseled on managing expectations as treatments commonly afford only temporary relief.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The International Headache Society defines trigeminal neuralgia (TN) as electric shock-like pains along the trigeminal nerve distribution that lasts up to 2 min and may be spontaneous or evoked [18]. With an annual incidence of 4–5 per 100,000 persons per year [9], the classic etiology is compression of the trigeminal root entry zone by blood vessels, primarily the superior cerebellar artery [5, 6]. A small subgroup of TN cases (2–4 %) is caused by multiple sclerosis (MS)-related demyelination of trigeminal nerve projections within the brainstem [5, 9].

When trigeminal symptoms become medically intractable or intolerance to drug side effects occur, neurosurgical procedures may be considered. Microvascular decompression of the trigeminal nerve is potentially curative when TN is caused by neurovascular compression. Alternatively, or in the absence of neurovascular compression (e.g., MS-TN), a variety of nerve injury or rhizotomy procedures may be available. These often provide only temporary pain relief but can be repeated if TN pain recurs and again becomes medically refractory.

Several studies have concluded that the pain recurrence following rhizotomies were higher in patients with MS-TN than classical TN [1,2,3, 10, 15]. Due to scarcity of comparative literature, no consensus has been reached on the choice procedure for MS-TN patients such that the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurological Societies concluded “There is insufficient evidence to support or refute the effectiveness of the surgical management of TN in patients with MS” and recommend only medically refractory MS-TN patients were candidates for surgical intervention [4]. Additionally, no data exists on the actual incidence of medically intractable MS-TN. Thus, the aim of this study was to analyze the utilization and outcomes of surgical procedures for MS-TN in Manitoba.

Methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the University of Manitoba Research Ethics Board (Approval #: HS16272).

Subjects

All Manitoban patients that underwent surgery for MS-TN at the Winnipeg Centre for Cranial Nerve Disorders between 2001 and 2014 were identified from a prospectively maintained database. These subjects had failed medical therapy preceding each operation.

Data collection

Patient medical charts consisting of referral letters, consultations, imaging reports, operative and follow-up notes were reviewed with relevant information compiled in a database for analysis. All procedures, including initial and subsequent, were recorded for every patient. Follow up was conducted through clinic visits and telephone calls in which patients were questioned about their TN pain and post-operative complications including but not limited to numbness, weakness, dysesthesia, and infection.

Surgical procedures

As a general treatment philosophy, the choice of surgical modality was considered on the basis of pain severity, urgency for pain relief, pain distribution, and patient preference. GammaKnife rhizotomy was expected to provide a slower onset of pain relief over weeks to months compared to the percutaneous rhizotomies. Balloon compression rhizotomy was utilized to alleviate V1 pain, while glycerol rhizotomy was used to target the V2 and V3 distributions. The anticipated degree of induced nerve injury was least with GammaKnife and greatest with balloon compression; a more severe injury technique that was generally elected after failure of milder rhizotomies. Open surgical partial sensory rhizotomy (Dandy procedure) was reserved as a “last measure” in this cohort, after multiple failed rhizotomies, due to the associated risks of a craniectomy and potential for severe sensory loss.

Outcome measurement

The primary treatment outcome was time-to-fail (TTF), which is defined as the interval between the surgical intervention and a subsequent procedure. Patients’ specific pain levels were recorded utilizing the Barrow Neurological Institute (BNI) Pain Intensity score, however were not analyzed in this study, as individual patient pain scores and medication usage were inconsistent and fluctuated prior to surgical interventions. Rather, we utilized time-to-fail as it was felt that this was the most objective, quantifiable and interpretable measure given the number of procedures analyzed. The indications for retreatment in all patients were standard: BNI scores of 4 or 5 or medication intolerance in the context of severe pain and was then typically offered within 1 to 2 weeks.

Complication assessment

Post-operative complications were attributed to the previous procedure if they did not exist pre-operatively. This prevented mistakenly assigning complications to procedures when patients had pre-existing deafferentation pain or sensory symptoms.

Bias

All TN surgery procedures in the province were performed by the senior author (A.M.K.) and selection of operation was based upon severity of symptoms, distribution of pain as well as patient and surgeon preferences. To minimize the confounding effect of past procedures on pain modulation, first and subsequent interventions were analyzed separately. Subsequent procedures were analyzed collectively, as there were multiple variations of procedures in order and number.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier method was applied to the TTF data collected on each procedure. Survival curves were generated utilizing IBM SPSS statistical software (version 24). The log-rank test was used for comparisons of TTF between initial GammaKnife versus percutaneous rhizotomy and initial versus repeat treatments. A two-sided Student’s t test was used for comparison where appropriate and P values of < 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Results

Twenty-one Manitoba patients, 13 females and eight males, were surgically treated for their MS-related TN in a 14-year period (Table 1). Seven or these patients (four females and three males) were diagnosed with bilateral TN; however, in two patients (one female and one male) the symptoms were medically managed on one side. Of the 26 sides that required neurosurgical intervention, 14 were left-sided and 12 were right-sided. At the time of first procedure, pain distribution along the trigeminal nerve was as follows: V1 in one patient, V2 in two patients, V3 in six patients, V2–V3 in 11 patients, V1–V3 in four patients, and unknown in two patients. At last follow-up, one patient with V1 symptoms developed pain in the V2 and V3 distributions and two patients with V2 and V3 pain progressed to include V1 symptoms. The mean age at TN diagnosis was 53 ± 8 years and the first surgery was performed at a mean age of 57 ± 8 years.

The incidence of medically refractory MS-TN was 1.2 cases per million persons per year in Manitoba. In total, 21 MS patients, with 26 medically intractable sides, underwent 99 neurosurgical procedures for TN, an average of 4.7 procedures per patient (range, 1–16), during a median follow-up time of 59 months (range, 13–158 months).

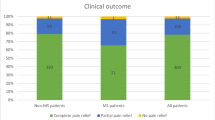

Of the 26 treated sides, the first procedure breakdown was as follows: 13 GammaKnife (80 Gy maximum dose) and 13 percutaneous rhizotomies (ten glycerol and three balloon). Due to the similarity in operative technique and effect on pain modulation, glycerol rhizotomy and balloon compression rhizotomy were analyzed together as percutaneous rhizotomy. The average ages at initial surgery GammaKnife and percutaneous rhizotomies were 56 ± 8 and 57 ± 9 years (p = 0.85), respectively. Initial pain relief defined as BNI 1–3 was achieved in 12/13 (92%) sides that underwent GammaKnife and 10/13 (77%) sides that underwent percutaneous rhizotomy (p = 0.30). As of the last follow-up, two GammaKnife (13 and 37 month’s follow-up time) and one percutaneous rhizotomy (126-month follow-up time) patients had required no repeat surgeries. The remaining 88% (23/26 sides) of first treatments failed with BNI scores of IV–V with intolerable pain or medication side effects. Additional surgeries were then performed. The average TTF for the first GammaKnife and percutaneous rhizotomy procedures were 12 ± 8 and 19 ± 17 months, respectively; this difference in TTF was not statistically significant (log-rank test, p = 0.64, Fig. 1). The three treatments that did not require additional surgeries were excluded from TTF calculations.

Sixty-seven additional procedures were required for the 23 sides that failed initial surgery; 24 GammaKnife and 43 percutaneous rhizotomies (19 glycerol and 24 balloon compression, Fig. 2). The average TTF for these GammaKnife and percutaneous rhizotomies were 17 ± 22 and 13 ± 15 months, respectively (Table 2). The difference of TTF between subsequent procedures compared to the initial procedure was not statistically significant (log-rank test, p = 0.2, Fig. 3 for GammaKnife and p = 0.67, Fig. 4 for percutaneous rhizotomy).

Four patients (five sides) ultimately developed severe recurrent MS-TN pain, despite multiple procedures and were therefore scheduled to undergo open surgical rhizotomy. In two of these patients, significant neurovascular compression was discovered at surgery leading to a microvascular decompression rather than nerve sectioning. One patient has maintained pain relief (80-month follow-up time) while the other developed recurrent pain and underwent open surgical partial sensory rhizotomy at 8 months. Among the four open surgical partial sensory rhizotomies performed in this cohort, none required retreatment and telephone follow-up also confirmed that all remained pain-free and off medications at 4, 12, 65, and 110 months, postoperatively.

No patients suffered any major surgical complications such as death, stroke or hemorrhage, infection or cerebrospinal fluid leak. There were no cases of anesthesia dolorosa, defined as constant, severe facial pain with associated numbness. Masseter weakness was reported after GammaKnife in two (6%) cases and percutaneous rhizotomies in four (7%) cases. One patient with medically refractory bilateral pain died of pancreatic cancer.

There were, however, a number of patients describing persisting procedure-related trigeminal dysesthesia not severe enough to be classified as anesthesia dolorosa. Dysesthesia (BNI Facial Numbness score III–IV) was reported for eight of 26 sides treated (four GammaKnife and four percutaneous rhizotomies). While most of these new dysesthesias developed after multiple procedures, one patient experienced this after their first GammaKnife rhizotomy. Persisting decreased sensation (BNI Facial Numbness score II) was reported after GammaKnife in five (14%) cases, and after percutaneous rhizotomies in 14 (25%) cases and after all four open surgical partial sensory rhizotomies.

We observed a mildly positive correlation between the degree of postoperative facial numbness (Table 3) and the time to fail for glycerol injection (r = 0.143, Fig. 5) and balloon compression (r = 0.124, Fig. 6). However, the correlation for these procedures did not achieve statistical significance (glycerol injection, p = 0.459 and balloon compression, p = 0.539).

Discussion

The incidence of MS-TN may be derived from the literature to be 1–2 cases/million/year [5, 9]. This value seemed to equal the incidence of medically refractory MS-TN we observed in this series. From this data, it may be inferred that the majority of MS-TN patients eventually fail pharmacologic treatment (i.e., suffering from intolerable pain or medication side effects) and require a neurosurgical procedure. This is in keeping with the aggressive nature of MS-TN. Compared to published literature on classical TN, we found MS-TN was diagnosed at a younger age (53 vs. 61 years old) and was more commonly bilateral (33 vs. 3%) [4, 20]. Also, nearly all MS-TN patients eventually became medically refractory compared to 33–50% of classical TN patients [22]. Furthermore, medications failed, on average, 5 years earlier in the MS-TN cohort and these patients were 13 years younger at the time of first surgery than their classical TN counterparts [7, 14, 17].

The conventional rhizotomies, GammaKnife, and percutaneous rhizotomies, provided only temporary relief for MS-TN and multiple procedures were necessary for the majority of patients. In contrast, most classical TN cases may be cured with microvascular decompression, an option not typically effective for MS-TN. An average of 4.7 procedures per patient were required over a mean follow-up of 59 months. Moreover, the primary outcome measure of TTF often did not represent an earlier failure point of ineffective pain control and mediation side effects. Prior to subsequent surgeries, all patients had recurrent TN pain with BNI scores of 4 and 5 after treatment with medications that eventually failed to provide adequate relief. Prophylactic procedures were not employed before medication failure due to the limited duration of their effectiveness and the risk of post-operative complications including deafferentation pain, which may sometimes be more disturbing than pre-operative TN pain. In this series, new deafferentation pain was encountered in eight of 26 sides (31%) usually after multiple rhizotomy procedures. Previous authors have found a positive correlation between degree of post-operative numbness and duration of pain relief among patients undergoing radiofrequency rhizotomy. This, however, was not the case after glycerol rhizotomy and balloon compression rhizotomy in our series and represents an interesting point of future study [17].

A comparison of outcomes between GammaKnife and percutaneous rhizotomies is hindered by differing treatment effects and indications. In patients with intolerable pain requiring immediate relief, percutaneous rhizotomy was preferred to GammKnife as the latter often required weeks to months for full treatment effect. Therefore, GammaKnife was generally reserved for patients with less severe treatment urgency and levels of pain. The effects of this selection bias may have influenced the apparent treatment effectiveness between techniques, as pre-operative pain levels may have been significantly different. We found that the group undergoing initial percutaneous rhizotomies had more than twice as many additional treatments than the initial GammaKnife group (52 vs. 21). It is unclear whether the difference in number of treatments required for pain modulation were related to the difference in severity of the disease, difference in total follow-up periods (126 months for percutaneous rhizotomies vs. 38 months for GammaKnife) or efficacy of the treatment modality.

Open surgical partial sensory rhizotomy provided long-term pain relief in the small number of patients treated. Preliminary results from this series are promising with no patients requiring retreatment at time of last follow-up, although the potentially increased risk of dysesthesia and ocular complications limits its usage as an initial treatment. No serious complications were encountered, although all patients experienced some anticipated facial numbness as a consequence of partial nerve sectioning. Partial sensory rhizotomy was typically employed later in the disease course after multiple previous procedures (range, 4–11) and nearly 8 years after the first surgery. While this period represented a significant period of potential suffering prior to partial sensory rhizotomy, enthusiasm for earlier utilization of this invasive procedure is balanced against the potential that long-term pain relief is sometimes achieved with conventional rhizotomies that may carry a reduced risk of deafferentation pain, anesthesia dolorosa, and ocular complications. Our data may be interpreted to support earlier use of the open partial sensory rhizotomy in patients with recurrent TN after multiple failed surgeries, although not as an upfront treatment. As noted above, this series includes a small number of such patients and therefore cannot make any strong conclusions or treatment recommendations. Given our promising preliminary observations, further study of the role of partial sensory rhizotomy in MS-TN patients seems warranted in order to provide further information regarding treatment efficacy, complication rates, and time to treatment failure in this patient population.

Two patients scheduled for open partial sensory rhizotomy were found to have significant neurovascular compression intra-operatively, which was not seen on pre-operative imaging. Microvascular decompression was then performed and provided long-lasting pain relief in one patient. In some cases, advanced MRI techniques with sequences, such as CISS and FIESTA, may be effective in identifying MS patients with neurovascular compression that should be considered for microvascular decompression. This has been the practice at our center, although to date few patients with MS-TN and associated brainstem plaques of demyelination have been found to have concurrent neurovascular compression on preoperative diagnostic imaging.

Literature review

Several MS-TN series have been published on the surgical outcomes for various rhizotomy procedures. These studies generally analyzed the results of a single type of operation, did not distinguish between first or subsequent treatments, or account for other treatment modalities. Therefore, a direct comparison with our multimodality longitudinal series is subject to several lines of bias and confounding factors. Nevertheless, in order to draw comparisons between these series and our own, we separately analyzed our patients that underwent initial GammaKnife and percutaneous rhizotomies (Tables 4 and 5).

Strengths and limitations

Our population-based study encompassed all MS patients in Manitoba that underwent any form of TN surgery. All of the procedures were performed at the Winnipeg Centre for Cranial Nerve Disorders by the senior author (A.M.K), and long-term follow-up was obtained for all patients with reasonable confidence that every procedure performed in the province was captured in the study.

A limitation of this study was the small sample size of only 21 patients with 26 surgically treated sides, resulting in a low statistical power. Moreover, the true incidence and prevalence for MS-TN in Manitoba is not known.

Additionally, the study was retrospective in nature and insufficient data was available in some medical charts to assess certain outcome measures such as initial pain-free response and pain-free interval. Although BNI scores were recorded for all patients, we found this to be a difficult outcome measure to analyze and interpret given the longitudinal nature of our study with multiple procedures, varying pain scores over time and varying follow-up intervals and duration. Rather, we elected to analyze time to treatment failure as the primary outcome measure for this longitudinal study. We felt that TTF provided the most objective measure of disease severity and impact on patient quality of life and represented a point in the disease course in which the patient and clinician felt the pain was sufficiently severe and persistent enough to accept the risks of a repeat procedure and warrant treatment. Repeat treatment was offered to patients with severe, persistent pain recurrence that was not adequately controlled with medications (BNI 4 or 5) or cases in which patients could not tolerate increased doses of medications required for pain control; the majority of these cases were BNI 5. Admittedly, our outcome measure of TTF does not quantify the percentage of patients with complete pain relief, completely pain-free intervals or time to pain recurrence, which are outcome measures commonly utilized in the literature. As demonstrated in our study, the disease course for this particular subgroup of TN patients is often characterized by years of suffering with severe, medically refractory pain requiring multiple, frequent procedures to provide pain relief or simply pain improvement. Therefore, the goal of treatment in these patients is often to provide the greatest degree of pain relief for the longest period of time rather than the expectation of complete pain relief, which is more commonly seen in cases of classical TN. As such, we feel that TTF represented the most appropriate outcome measure to assess disease severity and treatment efficacy given the nature of this longitudinal, multimodality study and this challenging patient population.

Conclusions

The incidence of medically refractory MS-TN in Manitoba was 1.2 per million people per year. There was a high failure rate for standard rhizotomies, and multiple retreatments were necessary for symptom relief. Overall, initial surgery for MS-TN failed in 85% after GammaKnife and 92% after percutaneous rhizotomies. An additional 73 treatments on 23 sides were required over the follow-up period. MS-TN remains a challenging clinical entity commonly requiring lifetime medical management and as evidenced by our series, multiple surgical procedures over the lifespan of the patient. Our report provides useful graphical outcome data highlighting the high rate of pain recurrence in this patient population, which can be used when counseling patients regarding treatment options and discussing realistic treatment goals, which may influence patient expectations and satisfaction with treatment.

References

Ariai MS, Mallory GW, Pollock BE (2014) Outcomes after microvascular decompression for patients with trigeminal neuralgia and suspected multiple sclerosis. World Neurosurg 81(3–4):599–603

Brisman R (2000) Gamma knife radiosurgery for primary management for trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg 93(Suppl 3):159–161

Cheng JS, Sanchez-Mejia RO, Limbo M, Ward MM, Barbaro NM (2005) Management of medically refractory trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurosurg Focus 18(5):e13

Cruccu G, Gronseth G, Alksne J, Argoff C, Brainin M, Burchiel K, Nurmikko T, Zakrzewska JM (2008) AAN-EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia management. Eur J Neurol 15(10):1013–1028

Jensen TS, Rasmussen P, Reske-Nielsen E (1982) Association of trigeminal neuralgia with multiple sclerosis: clinical and pathological features. Acta Neurol Scand 65(3):182–189

Maarbjerg S, Wolfram F, Gozalov A, Olesen J, Bendtsen L (2015) Significance of neurovascular contact in classical trigeminal neuralgia. Brain 138(2):311–319

Maesawa S, Salame C, Flickinger JC, Pirris S, Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD (2001) Clinical outcomes after stereotactic radiosurgery for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg 94(1):14–20

Mallory GW, Atkinson JL, Stien KJ, Keegan BM, Pollock BE (2012) Outcomes after percutaneous surgery for patients with multiple sclerosis-related trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery 71(3):581–586

Manzoni GC, Torelli P (2005) Epidemiology of typical and atypical craniofacial neuralgias. Neurol Sci 26(SUPPL. 2):65–67

Martin S, Teo M, Suttner N (2015) The effectiveness of percutaneous balloon compression in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosurg 123(6):1507–1511

Mathieu D, Effendi K, Blanchard J, Séguin M (2012) Comparative study of gamma knife surgery and percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosurg 117(Suppl(December)):175–180

Mohammad-Mohammadi A, Recinos PF, Lee JH, Elson P, Barnett GH (2013) Surgical outcomes of trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurosurgery 73(6):941–950

Montano N, Papacci F, Cioni B, Di Bonaventura R, Meglio M (2012) Percutaneous balloon compression for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis. Analysis of the potentially prognostic factors. Acta Neurochir 154(5):779–783

Nurmikko TJ, Eldridge PR (2001) Trigeminal neuralgia--pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. Br J Anaesth 87(1):117–132

Resnick DK, Jannetta PJ, Lunsford LD, Bissonette DJ (1996) Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis. Surg Neurol 46(4):358-61–358-62

Rogers CL, Shetter AG, Ponce FA, Fiedler JA, Smith KA, Speiser BL (2002) Gamma knife radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia associated with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosurg 97(5 Suppl):529–532

Sindou M, Tatli M (2009) Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia with thermorhizotomy. Neurochirurgie 55(2):203–210

Siqueira SRDT, da Nobrega JCM, de Siqueira JTT, Teixeira MJ (2006) Frequency of postoperative complications after balloon compression for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 102(5):e39–e45

Society IH, Icd IHSD, Paroxysmal A, Pain B, Attacks C, There D, Not E (2016) IHS Diagnosis ICD-10 13.1.1. 6–7

Tanrikulu L, Hastreiter P, Bassemir T, Bischoff B, Buchfelder M, Dörfler A, Naraghi R (2016) New clinical and morphologic aspects in trigeminal neuralgia. World Neurosurg 92:189–196

Tuleasca C, Carron R, Resseguier N, Donnet A, Roussel P, Gaudart J, Levivier M, Regis J (2014) Multiple sclerosis-related trigeminal neuralgia: a prospective series of 43 patients treated with gamma knife surgery with more than one year of follow-up. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 92(4):203–210

Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME (2014) Trigeminal Neuralgia BMJ 2014(February):g474

Zorro O, Lobato-Polo J, Kano H, Flickinger JC, Lunsford LD, Kondziolka D (2009) Gamma knife radiosurgery for multiple sclerosis-related trigeminal neuralgia. Neurology 73(14):1149–1154

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Conferences

1. Platform Speaker at University of Manitoba Department of Surgery Annual Research Day on January 13, 2016.

2. Platform Speaker at Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation 51st Congress in Quebec City on June 24, 2016.

3. Platform Speaker at University of Manitoba, UGME Research Symposium on August 18, 2016

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krishnan, S., Bigder, M. & Kaufmann, A.M. Long-term follow-up of multimodality treatment for multiple sclerosis-related trigeminal neuralgia. Acta Neurochir 160, 135–144 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3383-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3383-x