Abstract

Background

The use of endoscopes in transnasal surgery offers increased visualization. To minimize rhinological morbidity without restriction in manipulation, we introduced the mononostril transethmoidal-paraseptal approach.

Methods

The aim of the transethmoidal-paraseptal approach is to create sufficient space within the nasal cavity, without removal of nasal turbinates and septum. Therefore, as a first step, a partial ethmoidectomy is performed. The middle and superior turbinates are then lateralized into the ethmoidal space, allowing a wide sphenoidotomy with exposure of the central skull base.

Conclusions

This minimally invasive transethmoidal-paraseptal approach is a feasible alternative to traumatic transnasal concepts with middle turbinate and extended septal resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Relevant surgical anatomy

The aim of our mononostril transethmoidal-paraseptal approach is to create sufficient space for exposure of the central skull base while minimizing sinonasal injury (Fig. 1) as an alternative to traumatic approaches with extensive septal and turbinate resection causing subsequent postoperative nasal morbidity [6, 8].

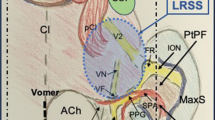

The intranasal septum, inferior, middle and superior turbinates, epipharynx, choana, and sphenoid ostium should be clearly identified within the main nasal cavity (Fig. 2). The olfactory epithelium, extending 2 cm along the supero-posterior septum to the upper part of the superior and middle turbinates [9], has to be preserved. For intraoperative orientation during ethmoidectomy, the natural ostium of the maxillary sinus, uncinate process, ethmoidal bulla, middle turbinate’s basal lamella, and the posterior ethmoidal cells have to be identified. Within the sphenoid sinus, the parasellar course of the optic nerves and carotid arteries, the fontal skull base, sellar floor, and the clivus have to be recognized to avoid complications.

First inspection of the left nasal cavity (a). After nasal decongestion, anatomical landmarks of the anterior nasal cavity can be identified, e.g., the septum, the inferior, and middle turbinates (b). Superiorly, the head and axilla of the middle turbinate and the uncinate process are recognized (c). Dissecting posteriorly between the inferior turbinate and the tail of the middle turbinate, the epipharynx becomes evident (d)

Description of the technique

Patients are placed supine with the head slightly elevated to lower the venous pressure, reclined, and slightly rotated for a more ergonomic working position (Fig. 3). After general anesthesia and navigation system setup, cottonoid pads, impregnated with epinephrine and tetracaine, are successively inserted towards the olfactory cleft, middle meatus, and the sphenoethmoid recess for mucosal decongestion.

The side for the unilateral approach is determined based on individual anatomical conditions and location of the lesion to achieve optimal surgical access.

In a first step, after identification of intranasal landmarks, the middle turbinate is gently medialized exposing the middle meatus. The uncinate process is identified, incised with a curved knife and partially resected (Fig. 4a). After identification of the maxillary sinus, the ethmoidal bulla is opened (Fig. 4b). Afterwards, the basal lamella of the middle turbinate is partially removed to gain access to the posterior ethmoidal cells (Fig. 4c). The antero-lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus is opened after complete anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy, exposing the lateral sphenoid sinus (Fig. 4d).

In the first step of dissection, the middle turbinate is gently medialized exposing the middle meatus. The uncinate process is identified and incised with a curved knife (a). After controlling the natural ostium of the maxillary sinus, the ethmoidal bulla is opened (b). The basal lamella of the middle turbinate is partially removed to gain access to the posterior ethmoidal cells (c). The antero-lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus is opened after completing the partial anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy (d)

Now, the key step of the technique follows: the middle and superior turbinates are gently lateralized into the space created with the ethmoidectomy (Fig 5a). Thereby, the natural ostium of the sphenoid sinus can be exposed through a unilateral approach without turbinate resection.

The key step of the technique remains the lateralization of the middle and superior turbinates into the space created with the ethmoidectomy (a). Within the sphenoethmoidal recess, the posterior septal mucosa is incised and mobilized inferiorly (b) and the rostrum is removed saving the surrounding nasal mucosa (c). The transethmoidal paraseptal approach allows wide bilateral exposure of the sphenoid sinus for safe and unhindered tumor resection (d)

In the sphenoethmoidal recess, the posterior septal mucosa is incised and mobilized inferiorly (Fig. 5b). Now, the anterior sphenoidal wall as well as the rostrum are removed (Fig. 5c). Thereby, a wide bilateral sphenoidotomy is created, exposing the sphenoid sinus and central skull base for unhindered and well-visualized tumor resection (Fig. 5d).

By creating this minimally invasive unilateral exposure, the nasal septum and turbinates remain intact (Fig. 6). Nevertheless, the target lesion can be approached bimanually without restriction of surgical movements.

Indication

Indications for a mononostril approach include pituitary adenomas and central skull base lesions such as chordomas and craniopharyngiomas.

Limitations

This approach is limited to lesions confined to the sellar region. Pathologies with a wide lateral extension (e.g. large clival chordomas) may not be sufficiently treated mononostrally, making binostril expanded approaches necessary.

How to avoid complications

To achieve optimal exposure, endoscopic transnasal surgeons often use a wide approach causing extensive intranasal injury [6]. However, rhinological symptoms secondary to a destructive surgery may permanently impair patients’ postoperative quality of life. Delayed secondary healing, intranasal adhesions, and extensive crusting may lead to symptoms such as a congested nose, nasal discharge, hyposmia and facial pain [2, 3, 7, 8]. With our technique, we have introduced rhinosurgical principles based on sinonasal physiology into transnasal neuroendoscopy in order to avoid the complications mentioned above [1, 4]. During a mono-nostril approach, the second nostril stays untouched, and therefore immediate postoperative recovery is faster since breathing and olfaction are possible through the second nostril.

Specific complications of this mononostril transethmoidal-paraseptal approach are mainly related to the transnasal part. While performing the ethmoidectomy, the lamina papyracea may be perforated with possible consecutive intraorbital complications (hematoma, injury to muscles and nerves leading to double vision/loss of vision). The eyes of the patients should be visible during the entire surgery to allow constant surveillance. Furthermore, it is of great importance to clearly identify the natural ostium of the maxillary sinus prior to opening the ethmoidal bulla. Working with an experienced sinonasal surgeon decreases approach-related complications [1].

Other complications of transnasal endoscopic neurosurgery such as cardiocirculatory events while placing the epinephrine pads for decongestion, CSF leakage, and injury to the carotid artery or optic nerve can be avoided with concise communication with the anesthesiologist and careful preoperative evaluation of the individual anatomy as well as intraoperative use of neuronavigation.

Specific perioperative considerations

Our patients receive detailed preoperative rhinological workup including CT of the paranasal sinuses, endonasal endoscopic examination, bilateral testing of the olfactory function and objective measurement of nasal quality of life (SNOT-22) [5]. After surgery nasal douching and nasal ointment are applied to help wound healing, prevent drying out or excessive crusting. Intranasal endoscopy is repeated on the 1st to 3rd postoperative days to clean the nasal airways. Routine endoscopic examination, evaluation of olfactory function, and SNOT-22 measurement are repeated at 1 month and 1 year after surgery.

A postoperative MRI is performed within 24–48 h to exclude surgical complications and evaluate tumor resection. Neurosurgical follow-up examinations are scheduled after 3 and 12 months with repeat MRI scans.

Additionally, all patients are perioperatively also cared for by an endocrinologist.

Specific information to give to the patient about surgery and potential risks

Patients need to be informed about the general surgical risks, specific risks as mentioned above, the perioperative and follow-up examinations (MRI, CT, rhinology, endocrinology).

Our patients receive additional information about the benefits of endoscopic surgery (direct visualization of deep structures), the rhino-neurosurgical teamwork (two different specialties, four hands, two brains) as well as the possible improvement of their nasal function and quality of life (SNOT-22) based on our experience.

Summary and key points

-

1.

Transnasal endoscopic approaches offer increased visualization in the deep and narrow surgical field.

-

2.

Without the use of a nasal speculum, surgeons often remove nasal turbinates and the posterior nasal septum or use binostril approaches for better exposure.

-

3.

Destructive transnasal endoscopic surgery, however, may increase postoperative nasal complaints with a significant effect on quality of life.

-

4.

The aim of modern minimally invasive transnasal endoscopy is to achieve maximal exposure while minimizing approach-related nasal morbidity.

-

5.

The objective of this approach is exposure of the central skull base unilaterally without removal of the nasal turbinates or septum, thus preserving normal anatomy and nasal function.

-

6.

The main step of our technique is the partial ethmoidectomy, creating significantly more space in the nasal cavity without a negative influence on postoperative nasal function.

-

7.

Gently lateralizing the intact middle and superior turbinates into the space, created by the ethmoidectomy, establishes an enlarged endonasal paraseptal corridor.

-

8.

Exposing the sphenoethmoid recess, bilateral wide sphenoidotomy can be performed without extensive posterior septal resection.

-

9.

Despite its unilateral design, the transethmoidal paraseptal approach creates sufficient exposure of the central skull base for unhindered surgical manipulation.

-

10.

This technique provides the greatest possible protection of the nasal mucosa and the olfactory cleft with patency of the natural sinus ostia preserving physiological sinonasal drainage and normal postoperative nasal function.

References

Briner HR, Simmen D, Jones N (2005) Endoscopic sinus surgery: advantages of the bimanual technique. Am J Rhinol 19:269–273

Friedman M, Caldarelli DD, Venkatesan TK, Pandit R, Lee Y (1996) Endoscopic sinus surgery with partial middle turbinate resection: effects on olfaction. Laryngoscope 106:977–981

Gliklich RE, Metson R (1995) The health impact of chronic sinusitis in patients seeking otolaryngologic care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 113:104–109

Graham SM, Iseli TA, Karnell LH, Clinger JD, Hitchon PW, Greenlee JD (2009) Endoscopic approach for pituitary surgery improves rhinologic outcomes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 118:630–635

Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, Lund VJ, Browne JP (2009) Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin Otolaryngol 34:447–454

Kassam AB, Prevedello DM, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Thomas A, Gardner P, Zanation A, Duz B, Stefko ST, Byers K, Horowitz MB (2011) Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: analysis of complications in the authors’ initial 800 patients. J Neurosurg 114:1544–1568

Marchioni D, Alicandri-Ciufelli M, Mattioli F, Marchetti A, Jovic G, Massone F, Presutti L (2008) Middle turbinate preservation versus middle turbinate resection in endoscopic surgical treatment of nasal polyposis. Acta Otolaryngol 128:1019–1026

Rice DH, Kern EB, Marple BF, Mabry RL, Friedman WH (2003) The turbinates in nasal and sinus surgery: a consensus statement. Ear Nose Throat J 82:82–84

Thompson CF, Kern RC, Conley DB (2015) Olfaction in endoscopic sinus and skull base surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 48:795–804

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Prof. Dr. med. R. Reisch and KD Dr. med. H. R. Briner are consultants of Karl Storz GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

The video “trans-ethmoidal, paraseptal approach to the sella” illustrates the main steps of a minimally invasive, mono-nostril approach to the sella preserving the middle turbinate and the septum, yet allowing a mono-nostril bimanual resection. (MP4 299966 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reisch, R., Briner, H.R. & Hickmann, AK. How I do it: the mononostril endonasal transethmoidal-paraseptal approach. Acta Neurochir 159, 453–457 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3075-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3075-6