Abstract

Purpose

Surgical site infection (SSI) occurs at a high rate after ileostomy closure. The effect of preventive negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) on SSI development in closed wounds remains controversial. We conducted a prospective multicenter study to evaluate the usefulness of preventive NPWT for SSI after ileostomy closure.

Methods

From January 2018 to November 2018, 50 patients who underwent closure of ileostomy created after surgery for colorectal cancer participated in this study. An NPWT device was applied to each wound immediately after surgery and then treatment was continued for 3 days. The primary endpoint was 30-day SSI, and the secondary endpoints were the incidence of seroma, hematoma, and adverse events related to NPWT.

Results

No patients developed SSI, seroma, or hematoma. Adverse events that may have been causally linked with NPWT were contact dermatitis in two patients and wound pain in one patient, and there were no cases of discontinuation or decompression of NPWT.

Conclusion

The use of NPWT following ileostomy closure may be useful for reducing the development of SSI in colorectal cancer patients. This is a prospective multicenter pilot study and we are planning a comparative study based on these successful results.

Trail registration

Registration number: UMIN000032053 (https://www.umin.ac.jp/).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) is one of the most common postoperative complications [1]; it prolongs hospital stays, reduces patient satisfaction with treatment, and increases medical costs. In the previous reports, the duration of hospitalization was extended by 10.0–17.8 days and medical expenses were increased by USD 3945–5928 [2, 3]. Various measures have been taken to reduce the incidence of SSI, such as bowel preparation [4], the administration of appropriate perioperative antibiotics [4], skin disinfection [4], reduction of wound length [5], wound protection [4], use of absorbable sutures [4], wound irrigation with saline [6], and use of subcuticular sutures [7].

A diverting stoma may be created in cases of anal-preserving surgeries such as low anterior resection or intersphincteric resection (ISR) for rectal cancer to preemptively prevent anastomotic leakage. In any case, a stoma is an indispensable option in patients undergoing colorectal surgery. When constructing a diverting stoma, ileostomy is often selected, because it is easier to establish and close than a colostomy.

Various complications occur after ileostomy closure, such as SSI, seroma, hematoma, bowel obstruction, and postoperative paralytic ileus. SSI is a very common complication; its incidence after primary wound closure and subsequent ileostomy closure was reported to be as high as 40% [8, 9], which is one of the highest rates among all surgical procedures [5]. Generally, the risk factors for SSI are diabetes, smoking history, a high body mass index (BMI), long operative time, and blood loss [10]. There are several risk factors for SSI after ileostomy closure, namely wound dehiscence, subcutaneous fat thickness, and American Society of Anesthesiologists classification ≥ 3 [11].

Negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in the form of vacuum-assisted closure was first introduced in 1997 [12]. NPWT is a treatment that promotes wound healing by applying negative pressure to an infected wound in a closed environment. Two studies have demonstrated that SSI decreased by the application of preventive NPWT to closed laparotomy incisions [13, 14]. Preventive NPWT for primary wound closure was shown to reduce SSI in several meta-analyses that examined studies on abdominal and orthopedic surgery. In the setting of abdominal surgery, three randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated contradictory results. In an RCT of 50 patients, 25% of whom underwent colorectal operations, O’Leary found that the incidence of SSI was significantly lower in the NPWT group than in controls: 8.3% vs. 32.0%, respectively (p = 0.043) [15]. A meta-analysis by Sahebally recently showed that preventive NPWT for general abdominal surgery and colorectal resection reduced the incidence of SSI (odds ratio 0.25; 95% confidence interval, 0.12–0.52; p < 0.001) [16].

Two single-center studies demonstrated that preventive NPWT after ileostomy closure decreased the incidence of SSI. In the first study, Cantero et al. [17] reported that patients who received preventive NPWT did not develop SSI, but the pressure and duration of NPWT were not standardized. In the second study [18], NPWT was performed with a continuous negative pressure of 125 mmHg for 5 days, and the surgical procedure was standardized; the incidence of SSI decreased from 20 to 12.5% with preventive NPWT.

To eliminate any bias to the greatest extent possible, this prospective multicenter study established a protocol involving strict standardization of perioperative antibiotics, intestinal anastomosis, wound irrigation, and NPWT. As a preparatory step for future comparative studies, a pilot study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of preventive NPWT using this protocol.

Methods

This is a prospective multicenter pilot study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each participating center. All the patients provided their written informed consent. This study is registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (https://www.umin.ac.jp; registration number ID 000032053).

Patients

Patients who underwent temporary loop ileostomy created after surgery for colorectal cancer at a participating hospital between January 2018 and November 2018 were screened for the exclusion criteria, and if eligible, were asked to participate.

The inclusion criteria were patients with colorectal cancer who underwent elective closure of a loop ileostomy, and who were aged 20 years or older and who gave their consent to participate. The exclusion criteria were patients who had ileostomy-related wound infection or severe liver or renal dysfunction.

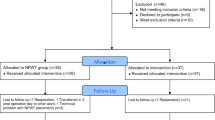

Interventions

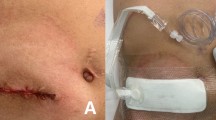

The study schedule is delineated in Fig. 1. All patients had no mechanical bowel lavage as a preoperative procedure. The intestinal canal was sutured closed, then the skin was closed, and the intestinal tract was buried. The skin was washed with chlorhexidine gluconate and the skin was disinfected with povidone iodine. The technique for ileostomy closure involved creating a spindle-shape incision around the ileostomy, followed by its complete mobilization. The ileostomy was extracted through this incision, and extracorporeal functional end-to-end anastomosis was performed. The fascia was closed with antibacterial polydioxanone (PDS) sutures. The wound was irrigated with 500 ml of saline, and then, skin closure was performed with interrupted dermal sutures using 4–0 PDS sutures (Fig. 2a, b). The NPWT system consisted of a GranuForm dressing (V.A.C.®; KCI, San Antonio, TX) covered with an adhesive sheet. This was attached immediately after surgery to a wound vacuum pump (V.A.C.®) set to 125 mmHg continuous negative pressure, and which was thereafter maintained for 3 days (Fig. 2c). To reduce any bias associated with the surgical procedure, we created a video of the procedure and standardized the protocol at all participating hospitals.

Each patient received 1 g of cefmetazole as prophylaxis before the skin incision and up to 24 h postoperatively every 8 h. The patients were followed up daily during hospitalization, and again at 30 days postoperatively.

The primary endpoint was the incidence of SSI at 30 days after surgery. SSI was defined according to the definition of the Centers for Disease Control and guidelines [4]: any infection of the superficial or deep tissues or the organ/space affected by surgery, and which occurs within 30 days of surgery. We diagnosed any patient with at least one of the following symptoms as having SSI: (1) purulent drainage from a superficial incision; (2) organisms isolated from an specimen obtained aseptically from a superficial incision or subcutaneous tissue; (3) any sign or symptoms of infection, including pain or tenderness; localized swelling; redness; a deliberate opening of the superficial incision by the surgeon, unless the incision was culture negative; and diagnosis of a superficial incisional SSI by the surgeon or attending physician. The primary endpoint was evaluated by a team led by a nurse certified in wound, ostomy, and continence nursing (WOCN) at postoperative days 3, 5, 7, and 30.

The secondary endpoints were the incidence of seroma, hematoma, and adverse events related to NPWT. NPWT could be interrupted for unavoidable reasons such as wound pain and contact dermatitis and resumed if there were no problems with the wound. Decompression was permissible if the pain was severe; the pressure was changed to 80 mmHg and NPWT was continued.

Follow-up was performed every day until discharge, as well as at 30 days after surgery. Wounds were checked by a physician at every follow-up examination (Fig. 2d, e, f). The above procedures for ileostomy closure, NPWT, and postoperative follow-up were performed at all centers in the same manner.

This study was completed and the finalization of data for analysis was performed in January 2019.

Results

This study included a total of 50 patients who underwent ileostomy closure for colorectal cancer. The median age was 65 years (range 34–80 years), and 62% were male. The median BMI was 22.5 kg/m2 (range 14.8–33.6 kg/m2). Seven patients had diabetes. There were 28 patients with a smoking history; of these, 19 were ex-smokers and nine were current smokers. Only one patient was a steroid user. The median preoperative albumin and total lymphocyte counts were 4.1 g/dl (range 3.5–4.6 g/dl) and 1394 mm3 (range 516–2533 g/dl). In addition, the median prognostic nutritional index was 47.9 (41.1–53.6). The operative procedure at primary tumor resection was low anterior resection in 35 patients and ISR in 12 patients, and 23 patients had received adjuvant chemotherapy. The median duration of ileostomy was 177 days (range 70–446 days) (Table 1). The median heights of the proximal and distal limbs of the ileostomy were 37 mm (range 5–50 mm) and 25 mm (range 5–30 mm), respectively. Before ileostomy closure, the level of parastomal dermatitis as measured by the discoloration, erosion and tissue overgrowth (DET) score was 2 (range 0–6).

The median operative time and blood loss volume were 78 min (range 41–174 min) and 5 ml (range 5–110 ml), respectively. The length of the skin incision was 60 mm (range 40–90 mm) (Table 2). Table 3 shows the operative outcomes of ileostomy closure. None of the patients were diagnosed with SSI, seroma, or hematoma. Postoperative paralytic ileus occurred in seven patients, with grade 3 severity in two patients according to the Clavien–Dindo Classification (CD). Adverse events that may have been causally linked with NPWT were contact dermatitis in two patients and wound pain in one patient, but all of these events were CD grade 2 or less. No patients experienced interruption or decompression of NPWT. The leachate volume collected at the NPWT was small amount in all cases. The median length of hospital stay was 6 days (range 4–19 days).

Discussion

In this study, preventive NPWT was associated with a reduced incidence of SSI after ileostomy closure in colorectal cancer patients. A previous study showed that preventive NPWT decreased the incidence of SSI, but did not eliminate its occurrence [18]. As a result, NPWT alone apparently cannot prevent SSI, and other factors such as the methods of anastomosis, wound irrigation, and suturing might be involved in the occurrence of SSI. It would be worthwhile to examine these factors in a multicenter prospective study that standardized ileostomy closure methods as much as possible. Our cohort in this multicenter study was relatively more likely to have risk factors for SSI such as high BMI, diabetes, and smoking history, but the results were positive despite the inclusion of patients with these comorbidities. While the previous study mentioned above was a single-center study [18], this study was the first to show the usefulness of preventive NPWT using a standardized approach with a multicenter design.

The manufacturer of the NPWT device used in this study generally recommends a suction pressure of 125 mmHg. Blood flow levels in wounds increased fourfold with a continuous negative pressure of 125 mmHg. The appropriate duration of the preventive NPWT is unclear. In the previous reports, preventive NPWT was conducted for 3–7 days [13, 15, 17,18,19]. The usual primary closed wound is closed in 48 h. When performing NPWT on infected wounds, the dressing is usually changed every 2–3 days and wounds are observed. We considered that preventive treatment should be performed with a minimum treatment period and medical materials. In this study, preventive NPWT was performed for 3 days with good results, and this treatment period was considered to be appropriate. It was considered that the protocol used in this study was safe and appropriate, because there were no cases in which NPWT was interrupted or in which decompression was necessary, and because there were a few adverse events that were definitively linked to NPWT.

Ileostomy construction procedures might be associated with the occurrence of SSI at ileostomy closure. An ileostomy proximal limb height of less than 10 mm was reported to be a risk factor for parastomal dermatitis and mucocutaneous separation after ileostomy creation [20]. There were also patients with a low ileostomy height and with parastomal dermatitis as determined by the DET score. Preventive NPWT may promote the healing of peristomal dermatitis and reduce the incidence of SSI. A consistent effort following ileostomy construction seems to be important for preventing the occurrence of SSI.

Patients in a previous study had a long operative time and large amount of bleeding [10]. This suggests that the occurrence of SSI could be reduced using the protocol in this study, in which abdominal wall closure was performed using absorbable dermal sutures and wound irrigation was conducted with pressurized saline; together, these approaches were reported to reduce SSI by 25 [21], 6 [22], and 1% [23].

It was reported that the hospital stay after ileostomy closure without preventive NPWT ranged from 6 to 9 days [18, 24]. Our cohort that did not undergo preventive NPWT had a median postoperative hospital stay of 9 days, whereas the median hospital stay in the cohort that underwent preventive NPWT was 6 days; thus, our protocol might shorten the length of hospital stay.

The medical cost of performing NPWT for 3 days was reported to be USD 330 [25]. Assuming that preventive NPWT reduces the incidence of SSI from 40 [3] to 3% [17, 18], the additional medical cost will be reduced by 80% even if preventive NPWT is performed on all cases. Kalady et al. report that the medical cost of performing an ileostomy closure is $ 4000 [26]. The average total medical cost is reduced by 30%. In conducting this research, education related to NPWT was provided to nurses certified in WOCN. The material was relatively easy to learn, and no extra cost was required.

As first described by Banerjee [27], the purse-string skin closure (PSC) technique reduced the incidence of SSI compared to the conventional linear closures (CLC) [28, 29]. Lee et al. [28] reported that PSC significantly reduced the incidence of SSI compared to CLC (2% vs 15%, p = 0.01), but it did not lead to patient satisfaction in terms of cosmesis and wound care. As shown in this study, if the incidence of SSI is reduced by adding NPWT to the CLC, patient satisfaction may be higher, and we will clarify this in future studies.

There are two main limitations associated with this study. First, this study was not a comparative study. Second, this study had a small sample size. Preventive NPWT was found to reduce the incidence of SSI from 20 to 12.5% [18], but if this efficacy could be further improved, this would reduce medical costs and shorten hospital stays. We considered that it was important to examine these issues prospectively, and a pilot study of 50 cases was performed. We are planning a randomized clinical trial based on these successful results.

Conclusion

The use of NPWT following ileostomy closure may be useful for reducing the development of SSI in colorectal cancer patients. This is a prospective multicenter pilot study and we are planning a comparative study based on these successful results.

References

Culver DH, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, et al. Surgical wound infection rates by wound class, operative procedure, and patient risk index. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Am J Med. 1991;91(3b):152s–s157157.

Kashimura N, Kusachi S, Konishi T, Shimizu J, Kusunoki M, Oka M, et al. Impact of surgical site infection after colorectal surgery on hospital stay and medical expenditure in Japan. Surg Today. 2012;42(7):639–45.

Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1990s;20(11):725–30.

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR, Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) hospital infection control practices advisory committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27(2):97–132 (quiz 3-4; discussion 96).

Yoshida K, Honda M, Kumamaru H, Kodera Y, Kakeji Y, Hiki N, et al. Surgical outcomes of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy compared to open distal gastrectomy: a retrospective cohort study based on a nationwide registry database in Japan. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;2(1):55–64.

Norman G, Atkinson RA, Smith TA, Rowlands C, Rithalia AD, Crosbie EJ, et al. Intracavity lavage and wound irrigation for prevention of surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;10:Cd012234.

Tsujinaka T, Yamamoto K, Fujita J, Endo S, Kawada J, Nakahira S, et al. Subcuticular sutures versus staples for skin closure after open gastrointestinal surgery: a phase 3, multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2013;382(9898):1105–12.

Gessler B, Haglind E, Angenete E. Loop ileostomies in colorectal cancer patients–morbidity and risk factors for nonreversal. J Surg Res. 2012;178(2):708–14.

Chun LJ, Haigh PI, Tam MS, Abbas MA. Defunctioning loop ileostomy for pelvic anastomoses: predictors of morbidity and nonclosure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(2):167–74.

Korol E, Johnston K, Waser N, Sifakis F, Jafri HS, Lo M, et al. A systematic review of risk factors associated with surgical site infections among surgical patients. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83743.

van Westreenen HL, Visser A, Tanis PJ, Bemelman WA. Morbidity related to defunctioning ileostomy closure after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and low colonic anastomosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(1):49–544.

Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38(6):563–76 (discussion 77).

Blackham AU, Farrah JP, McCoy TP, Schmidt BS, Shen P. Prevention of surgical site infections in high-risk patients with laparotomy incisions using negative-pressure therapy. Am J Surg. 2013;205(6):647–54.

Bonds AM, Novick TK, Dietert JB, Araghizadeh FY, Olson CH. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy significantly reduces surgical site infection in open colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(12):1403–8.

O'Leary DP, Peirce C, Anglim B, Burton M, Concannon E, Carter M, et al. Prophylactic negative pressure dressing use in closed laparotomy wounds following abdominal operations: a randomized, controlled, open-label trial: the P.I.C.O. trial. Annals Surg. 2017;265(6):1082–6.

Sahebally SM, McKevitt K, Stephens I, Fitzpatrick F, Deasy J, Burke JP, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy for closed laparotomy incisions in general and colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(11):e183467.

Cantero R, Rubio-Perez I, Leon M, Alvarez M, Diaz B, Herrera A, et al. Negative-pressure therapy to reduce the risk of wound infection following diverting loop ileostomy reversal: an initial study. Adv Skin wound care. 2016;29(3):114–8.

Poehnert D, Hadeler N, Schrem H, Kaltenborn A, Klempnauer J, Winny M. Decreased superficial surgical site infections, shortened hospital stay, and improved quality of life due to incisional negative pressure wound therapy after reversal of double loop ileostomy. Wound Repair Regen. 2017;25(6):994–1001.

Masden D, Goldstein J, Endara M, Xu K, Steinberg J, Attinger C. Negative pressure wound therapy for at-risk surgical closures in patients with multiple comorbidities: a prospective randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. 2012;255(6):1043–7.

Miyo M, Takemasa I, Ikeda M, Tujie M, Hasegawa J, Ohue M, et al. The influence of specific technical maneuvers utilized in the creation of diverting loop-ileostomies on stoma-related morbidity. Surg Today. 2017;47(8):940–50.

Ruiz-Tovar J, Alonso N, Morales V, Llavero C. Association between triclosan-coated sutures for abdominal wall closure and incisional surgical site infection after open surgery in patients presenting with fecal peritonitis: a randomized clinical trial. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2015;16(5):588–94.

Nikfarjam M, Weinberg L, Fink MA, Muralidharan V, Starkey G, Jones R, et al. Pressurized pulse irrigation with saline reduces surgical-site infections following major hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: randomized controlled trial. World J Surg. 2014;38(2):447–55.

Kobayashi S, Ito M, Yamamoto S, Kinugasa Y, Kotake M, Saida Y, et al. Randomized clinical trial of skin closure by subcuticular suture or skin stapling after elective colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2015;102(5):495–500.

Reid K, Pockney P, Pollitt T, Draganic B, Smith SR. Randomized clinical trial of short-term outcomes following purse-string versus conventional closure of ileostomy wounds. Br J Surg. 2010;97(10):1511–7.

Kim JJ, Franczyk M, Gottlieb LJ, Song DH. Cost-effective alternative for negative-pressure wound therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5(2):e1211.

Kalady MF, Fields RC, Klein S, Nielsen KC, Mantyh CR, Ludwig KA. Loop ileostomy closure at an ambulatory surgery facility: a safe and cost-effective alternative to routine hospitalization. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(4):486–90.

Banerjee A. Pursestring skin closure after stoma reversal. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(8):993–4.

Lee JT, Marquez TT, Clerc D, Gie O, Demartines N, Madoff RD, et al. Pursestring closure of the stoma site leads to fewer wound infections: results from a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(11):1282–9.

O'Leary DP, Carter M, Wijewardene D, Burton M, Waldron D, Condon E, et al. The effect of purse-string approximation versus linear approximation of ileostomy reversal wounds on morbidity rates and patient satisfaction: the 'STOMA' trial. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(11):863–8.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Drs. M. Kimura (Saiseikai Otaru Hospital), J. Kimura (Hokkaido Ohno Memoriarl Hospital), M Nishimori (Sapporo Dohto Hospital), H Ohshima (Sapporo Teishinkai Hospital), and S. Son (Saiseikai Otaru Hospital) for their assistance in this study.

Funding

This research was carried out using research funds from the Sapporo Medical University. There was no financial support from any companies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okuya, K., Takemasa, I., Tsuruma, T. et al. Evaluation of negative-pressure wound therapy for surgical site infections after ileostomy closure in colorectal cancer patients: a prospective multicenter study. Surg Today 50, 1687–1693 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-020-02068-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-020-02068-6