Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to examine the quality of data from the National Clinical Database (NCD) via a comparison with regional government report data and medical charts.

Methods

A total of 1,165,790 surgical cases from 3007 hospitals were registered in the NCD in 2011. To evaluate the NCD’s data coverage, we retrieved regional government report data for specified lung and esophageal surgeries and compared the number with registered cases in the NCD for corresponding procedures. We also randomly selected 21 sites for on-site data verification of eight demographic and surgical data components to assess the accuracy of data entry.

Results

The numbers of patients registered in the NCD and regional government report were 46,143 and 48,716, respectively, for lung surgeries and 7494 and 8399, respectively, for esophageal surgeries, leading to estimated coverages of 94.7% for lung surgeries and 89.2% for esophageal surgeries. According to on-site verification of 609 cases at 18 sites, the overall agreement between the NCD data components and medical charts was 97.8%.

Conclusion

Approximately, 90–95% of the specified lung surgeries and esophageal surgeries performed in Japan were registered in the NCD in 2011. The NCD data were accurate relative to medical charts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clinical registries and their data, which reflect real-world clinical practice and outcomes, are now being used to support healthcare quality improvement initiatives worldwide [1, 2]. The Japanese National Clinical Database (NCD), a registry involving a data collection scheme associated with surgical board certification, has provided several risk models for operative mortality and morbidities of commonly performed surgical procedures [3]. The NCD also provides a benchmark for reporting national and facility-specific risk-adjusted performance metrics to participating hospitals [4,5,6,7].

The usefulness of registry data is highly dependent on the quality of the data. However, it is difficult to assess the quality of registry data. Indeed, there are very few published reports describing the quality of registry data, although notable examples include those from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database [8, 9], the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program [10], the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery database [11], and the Japanese Congenital Cardiovascular Surgery Database [12]. Compared with clinical trials, the quality of data in clinical registries is not well monitored or evaluated, so the reliability of evidence from clinical registries is unclear. For example, a previous study revealed that patients with more severe disease were selectively not included in a registry [13].

The aim of this study was to assess the quality of data registered in the NCD in 2011. We evaluated the data in terms of the registration coverage and the accuracy of eight data components commonly recorded in surgical registries.

Methods

Data sources

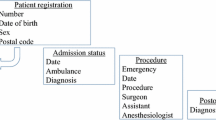

The NCD was established as part of a project to create a nationwide database that would allow researchers to assess surgical outcomes, with the goal of improving the quality of care (http://www.ncd.or.jp/). The NCD began collecting data in January 2011. It covers various specialties, including cardiac surgery, vascular surgery, gastroenterological surgery, pediatric surgery, breast cancer, and respiratory surgery. The participating hospitals are required to register all major surgical procedures. Clinical departments at each hospital participate in the NCD. A total of 1,165,790 surgical cases were submitted to the NCD in 2011 by 4313 participating departments at 3007 hospitals. The NCD covers approximately 50% of Japanese hospitals and approximately 80% of those that perform surgeries, according to a survey of medical institutions conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) [14].

Information is collected using data collection forms that contain 14 sections spanning patient characteristics and operative information as basic variables recorded for all cases. Each subspecialty collects up to 500 additional data components, including patient characteristics, preoperative risk, surgical information, postoperative complications, and outcomes. The variables recorded for cardiac surgery and gastroenterological surgery are nearly identical to those recorded in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database (http://www.sts.org/national-database) and the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/acs-nsqip). Data are submitted electronically and are automatically checked for logic, format, and range to reduce error due to data entry. Surgeons and data managers are responsible for registering the data in the NCD, and chief physicians are responsible for approving the data, confirming their integrity.

The Institutional Review Board of the Japan Surgical Society has approved data harvesting by the NCD [http://www.ncd.or.jp/about/ethical_considerations.html (in Japanese)], and the approval included opt-out clauses and processes for ensuring patient informed consent. Data registration at each hospital was approved by either the Institutional Review Committee or the hospital director.

Comparing NCD data with local government report data

To assess whether or not the data registration was complete, we compared the NCD data to regional government report data from eight regional health and welfare bureaus. This is a reporting that is mandatory for hospitals operating under Japanese universal health coverage, linked to facility reimbursement category certification [15]. The facilities report the number of specified surgical procedures performed under health insurance at all authorized medical institutions in Japan. The data are audited by the health and welfare bureaus via site visits. Twenty-five types of surgical procedures were recorded, including cerebral, ophthalmic, ear, lung, nasal, orthopedic, cardiac, and gastroenterological surgery. After assessing the comparability of the procedural definitions used in the regional government report data and NCD data, we selected lung surgeries and esophageal surgeries as target procedures (see supplemental table for the list of specific procedure types included). We compared the list of hospitals included in the regional government report data to those included in the NCD and confirmed the names and addresses of the corresponding hospitals.

Verifying the NCD data using on-site source data

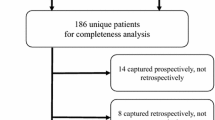

Of the 4313 participating sites, 21 were randomly selected for on-site data verification, and 19 of these sites agreed to our request. Verifications were conducted between August 2012 and March 2013. To confirm that data registered for all surgical cases were complete, we compared the operation logs at each facility with data registered in the NCD for 2829 cases (0.24% of all surgical cases registered in the NCD in year 2011). The operation logs included those managed by operating room staff, medical department staff, or those derived from the electronic medical records. We assessed whether or not the cases registered in the NCD could be matched with surgical logs using the date of surgery and NCD registration code.

To evaluate the accuracy of the registered data, up to 40 cases were randomly selected at each hospital for further data component verification. A total of 616 cases were selected (0.05% of all surgical cases in the NCD). The accuracy assessment included eight data components as follows: the patient’s date of birth, gender, admission date, whether or not an emergency ambulance was used, date of surgery, name of surgeon, data of discharge, and the patient’s status at discharge. We chose these variables because of their importance to the registry, the ability to objectively assess their correctness, and the standardized formats of recording these variables at hospitals [16]. Hospital records (operation records, admission and discharge summaries, and nursing records) were used as source documents. If the data registered with the NCD were the same as the source documents, the items were deemed to be “concordant”.

The present study was conducted by a team of non-clinicians that was commissioned by the NCD. Data were verified by staff who had general medical knowledge and standardized audit training. The main components of training included sessions on (1) overview of the NCD and its purposes/activities, (2) aims and purposes of the audit activities, (3) use of the NCD web-based case registration systems, (4) learning the definitions of the target data components, and (5) processes for data verification and recording of the results. The auditors were only allowed access to the patients’ medical records for verification purposes under conditions of maintaining patient confidentiality.

Statistical analyses

Comparing the NCD data to regional government report data

We compared the numbers of cases of the two surgical procedure groups (lung and esophagus) registered in the NCD relative to the regional government report data among two types of hospital groups: (1) all hospitals with either the regional government report data or NCD data, and (2) hospitals with at least one record of the procedure in both the regional government report and NCD. We also calculated the differences in the number of cases between the NCD data and the regional government report data at each hospital.

Verifying the NCD data using on-site source data

The completeness of case registration at 19 sites was assessed using on-site surgical logs. We estimated the proportion of confirmed registered cases among all surgical cases at each facility, and determined the number of duplicate registrations in the NCD. We assessed the accuracy of data entry by estimating the proportion of the concordance for the eight data items listed above. If the original data sources could not be identified using our standardized process of data verification, the data were excluded from the calculations. To assess how the accuracy of the data differed by whether or not the facility was an academic (university) hospital, we conducted an additional assessment stratified by this factor. All analyses were performed using the SAS software program, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Comparing the NCD data to regional government report data

We first assessed the registration coverage of NCD data relative to the regional government report data. The numbers of lung surgeries and esophageal surgeries reported to the regional health and welfare bureaus and in the NCD are listed in Table 1. For pneumonectomy, 48,716 cases were reported to the regional health and welfare bureaus, and 46,143 cases were registered in the NCD from a total of 1288 hospitals, yielding a coverage of 94.7% (46,143/48,716). In addition, 1010 hospitals with at least 1 procedure report in both the regional government report data and NCD data reported a total of 47,226 cases to the regional health and welfare bureaus and 45,648 cases to the NCD, yielding a coverage of 96.5% (45,648/47,226).

Regarding esophageal surgeries, 8399 cases were reported to the regional health and welfare bureaus, and 7494 cases were registered in the NCD from a total of 1087 hospitals, yielding a coverage of 89.2% (7494/8399). In addition, among 826 hospitals with reported cases in both databases, 8024 cases were reported in the regional report, and 7237 cases were registered in NCD, leading to a coverage of 90.2% (7237/8024).

Among the hospitals with reported cases in both databases, 21.9% of hospitals for lung surgery and 44.3% of hospitals for esophageal surgery had exact matching numbers of reports in the 2 databases, and 42.3% of hospitals for lung surgery and 70.7% of hospitals for esophageal surgery had numbers within ± 1 (Table 2).

Verifying the NCD data against hospital source data

We assessed the registration coverage and data accuracy of the NCD data against the hospitals’ surgery logs (Fig. 1). After assessing the completeness of registration, we excluded 1 of the 19 sites because the source data were insufficiently prepared or provided. A total of 2829 cases registered in the NCD were subjected to verification, and 2783 (98.4%) cases were confirmed to be valid, independent procedures. Twenty-six cases (0.9%) were falsely duplicated due to human error, and 20 cases (0.7%) could not be found in the surgical logs. A few cases were listed in surgical logs that were not registered in the NCD.

Of the 616 cases included in the assessment of data accuracy, seven were excluded because the patients’ charts were being used for patient care at the time of the audit. Therefore, 609 cases underwent verification, with a median of 39 cases per site (range 8–40 cases per site). The overall concordance of the eight variables was 97.8%, and all values for the individual variables were greater than 95% (Table 3). The discharge mortality status showed the greatest concordance at 99.4%. In general, there were no meaningful differences in these accuracy measures between academic and non-academic institutions (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study assessed the quality of the NCD data in 2011 in terms of its registration coverage and the accuracy of data entry. The registration coverage was high, at around 90–95%, for both procedures investigated (lung surgeries and esophageal surgeries) compared with the regional government report data. The eight data components that were adjudicated showed high concordance (≥ 95.0%) with the source data.

Many registries, especially ones that are not nationwide, do not report their coverage, making it difficult to compare the registration coverage with those of other registries. For cancer registries, registration coverage above 90% is considered to represent “silver-grade” coverage according to the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries [17]. A population-based US cancer registry reported a coverage of 80% or above [18], a Danish acute myeloid leukemia registry reported 99% coverage [19], and another Danish arthroplasty registry reported 70% coverage [20]. Two Swedish registries on cardiac surgery and esophagus/stomach cancer reported 99% [21] and 96% coverages [22], respectively. A low registration coverage may lead to selection bias. Therefore, the high registration coverage of the NCD supports the representativeness of the analyses based on the registry. It is easier to identify cases that are eligible for surgical registries than those eligible for registries in other settings (e.g., cancer). In the case of the NCD, we believe that requiring case registration for surgical certification was a major factor helping to ensure the complete recording of all cases at each facility. Regarding the few cases found in the surgical logs that were omitted from registration, the main reasons included human error or specific conditions, such as emergency surgeries during the night, surgeries with a low surgical difficulty, or surgeries conducted by visiting surgeons.

Basic variables, such as patient characteristics, discharge status after surgery, and discharge dates, were accurately recorded in the NCD, consistent with adjudication studies of other registries [8,9,10,11,12]. Some errors in data entry are expected in any registry. However, systematic and frequent errors may introduce bias. Accurate data entry is, therefore, essential for clinical registries and for their evaluation.

This is the first report to compare the coverage of the NCD relative to regional government report data, and the validity of our findings depends on the quality of the report used as the gold standard. In Japan’s healthcare system, all facilities are required to file all of their surgical procedures performed under universal healthcare insurance coverage to the regional health and welfare bureaus; therefore, in theory, such information should include 100% of major surgical procedures performed in Japan [23]. However, there remains a possibility of overreporting, since the reported numbers for particular procedures determine whether or not the facilities receive certification for specialty care. As the two surgical procedures that we referenced in the study are not used for such facility certification, we believe the risk of overreporting is minimal. Future studies may confirm our findings using different data sources, such as administrative claims data as the gold standard. In our study, on-site data identification and a comparison against the surgical logs complemented our assessment of the registration coverage of cases at these facilities. Therefore, it is important to elucidate how duplication and omission could occur in these nationwide registries. The sites included in the on-site data verification were randomly selected to avoid bias by selecting facilities with certain characteristics. However, due to time and cost constraints, we could only conduct on-site data verification at a small proportion of all sites involved in NCD activity.

A few limitations of our study should be noted. First, we were unable to compare all of the types of surgical procedures included in the regional government report data with the NCD data to assess registration coverage because the definitions of many procedures differed between the two databases. Furthermore, while the definitions of lung surgeries and esophageal surgeries were quite similar, small differences remained, as shown in the supplemental table. Second, not all hospitals in Japan participate in the NCD. Therefore, some facilities submitted data to the regional office but not the NCD. In addition, some facilities submitted data to the NCD but not to the regional office. We tried to identify and link as many facilities in the two databases as possible, but some remained unlinkable. Further and more granular investigation on the characteristics of these facilities with additional information collection may clarify the reasons for these discrepancies. Third, it was not possible to compare the NCD data and regional government report data at the individual case level because the government report does not provide the granularity necessary for such an analysis. Finally, due to time and cost constraints, on-site data adjudication was limited to a small number of variables. Therefore, we were unable to discuss the accuracies of some of the important variables in the database, especially the procedure type and postoperative complications. Data validation activities are now underway in many NCD registries, including the Japan Cardiovascular Surgery database, gastroenterological surgery database, breast cancer registry, vascular surgery registry, coronary intervention registry, and respiratory surgery database. Target data components for these validation studies conducted by the governing/database committees of each registry include specialty-specific data components, such as comorbidities and postoperative complications (e.g., reports by Tomotaki et al. [12] and Takahashi et al. [24]). While the activity is time- and effort-consuming, it builds the basis for scientific research conducted using these databases, and is, therefore, one of the most important activities for the governing/database committees.

Conclusion

This study showed high registration coverage of data in the NCD 2011 for the specified lung and esophageal surgeries. In addition, the NCD data showed high accuracy for the registration of basic variables, including patient characteristics and the discharge mortality status. Future studies should evaluate the accuracies of other important variables, such as postoperative complications and procedure types.

References

D’Agostino RS, Jacobs JP, Badhwar V, Paone G, Rankin JS, Han JM, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database: 2017 update on outcomes and quality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:18–24.

Cohen ME, Liu Y, Ko CY, Hall BL. Improved surgical outcomes for ACS NSQIP hospitals over time: evaluation of hospital cohorts with up to 8 years of participation. Ann Surg. 2016;263:267–73.

Miyata H, Gotoh M, Hashimoto H, Motomura N, Murakami A, Tomotaki A, et al. Challenges and prospects of a clinical database linked to the board certification system. Surg Today. 2014;44:1991–9.

Saze Z, Miyata H, Konno H, Gotoh M, Anazawa T, Tomotaki A, et al. Risk models of operative morbidities in 16,930 critically ill surgical patients based on a Japanese nationwide database. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1224.

Yokoo H, Miyata H, Konno H, Taketomi A, Kakisaka T, Hirahara N, et al. Models predicting the risks of six life-threatening morbidities and bile leakage in 14,970 hepatectomy patients registered in the National Clinical Database of Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5466.

Kurita N, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Shimada M, Imura S, Kimura W, et al. Risk model for distal gastrectomy when treating gastric cancer on the basis of data from 33,917 Japanese patients collected using a nationwide web-based data entry system. Ann Surg. 2015;262:295–303.

Gotoh M, Miyata H, Hashimoto H, Wakabayashi G, Konno H, Miyakawa S, et al. National Clinical Database feedback implementation for quality improvement of cancer treatment in Japan: from good to great through transparency. Surg Today. 2016;46:38–47.

Shroyer AL, Edwards FH, Grover FL. Updates to the data quality review program: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac National Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1494–7.

Grover FL, Shroyer AL, Edwards FH, Pae WE Jr, Ferguson TB Jr, Gay WA Jr, Clark RE. Data quality review program: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac National Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:1229–31.

Shiloach M, Frencher SK Jr, Steeger JE, Rowell KS, Bartzokis K, Tomeh MG, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:6–16.

Maruszewski B, Lacour-Gayet F, Monro JL, Keogh BE, Tobota Z, Kansy A. An attempt at data verification in the EACTS Congenital Database. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:400–4.

Tomotaki A, Miyata H, Hashimoto H, Murakami A, Ono M. Results of data verification of the Japan Congenital Cardiovascular Database, 2008 to 2009. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2014;5:47–53.

Elfström J, Stubberöd A, Troeng T. Patients not included in medical audit have a worse outcome than those included. Int J Qual Health Care. 1996;8:153–7.

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Survey of medical institutions of 2013. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/13/. Accessed 1 May 2017.

Kanto-Shinetsu Regional Bureau of Health and Welfare (in Japanese). https://kouseikyoku.mhlw.go.jp/kantoshinetsu/iryo_shido/sisetukijyunntodokede.html. Accessed 26 Oct 2017.

Miyata H, Tomotaki A, Okubo S, Motomura N, Murakami A, Kiuchi T, et al. Quality improvement initiative based on National Clinical Database (2) to enhance reliability and neutrality of quality assessment. Surg Ther. 2011;104:381–6.

The North American Association of Central Cancer Registries. https://www.naaccr.org/certification-criteria/. Accessed 26 Oct 2017.

Allemani C, Harewood R, Johnson CJ, Carreira H, Spika D, Bonaventure A, Ward K, Weir HK, Coleman MP. Population-based cancer survival in the United States: data, quality control, and statistical methods. Cancer. 2017;123(Suppl 24):4982–93.

Østgård LS, Nørgaard JM, Raaschou-Jensen KK, Pedersen RS, Rønnov-Jessen D, Pedersen PT, Dufva IH, Marcher CW, Nielsen OJ, Severinsen MT, Friis LS. The Danish National Acute Leukemia Registry. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:553–60.

Allepuz A, Serra-Sutton V, Martínez O, Tebé C, Nardi J, Portabella F, Espallargues M, en nombre del Registro de Artroplastias de Cataluña (RACat). Arthroplasty registers as post-marketing surveillance systems: the Catalan Arthroplasty Register. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57(1):27–37.

Vikholm P, Ivert T, Nilsson J, Holmgren A, Freter W, Ternström L, Ghaidan H, Sartipy U, Olsson C, Granfeldt H, Ragnarsson S, Friberg Ö. Validity of the Swedish Cardiac Surgery Registry. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivy030.

Linder G, Lindblad M, Djerf P, Elbe P, Johansson J, Lundell L, Hedberg J. Validation of data quality in the Swedish National Register for Oesophageal and Gastric Cancer. Br J Surg. 2016;103(10):1326–35.

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Outline of 2010 revision of medical fee (in Japanese). http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iryouhoken/iryouhoken12/index.html. Accessed 26 Oct 2017.

Takahashi A, Kumamaru H, Tomotaki A, Matsumura G, Fukuchi E, Hirata Y, Murakami A, Hashimoto H, Ono M, Miyata H. Verification of data accuracy in Japan Congenital Cardiovascular Surgery Database including its postprocedural complication reports. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2018;9:150–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the staff and academic societies involved in the National Clinical Database. AT, HK, and HM are affiliated with the Department of Healthcare Quality Assessment at the University of Tokyo, which is a social collaboration department supported by the National Clinical Database, Johnson & Johnson K.K., and Nipro corporation. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare. The data verification activities were supported by the National Clinical Database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tomotaki, A., Kumamaru, H., Hashimoto, H. et al. Evaluating the quality of data from the Japanese National Clinical Database 2011 via a comparison with regional government report data and medical charts. Surg Today 49, 65–71 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-018-1700-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-018-1700-5