Abstract

Purpose

In recent years, depression rates have been on the rise, resulting in soaring mental health issues globally. There is paucity of literature about the impact of depression on lumbar fusion for adult spine deformity. The purpose of this study is to investigate whether patients with depressive disorders undergoing lumbar deformity fusion have higher rates of (1) in-hospital length of stay; (2) ninety-day medical and surgical complications; and (3) medical reimbursement.

Methods

A retrospective study was performed using a nationwide administrative claims database from January 2007 to December 2015 for patients undergoing lumbar fusion for spine deformity. Study participants with depressive disorders were selected and matched to controls by adjusting for sex, age, and comorbidities. In total, the query yielded 3706 patients, with 1286 who were experiencing symptoms of depressive disorders, and 2420 who served as the control cohort.

Results

The study revealed that patients with depressive disorders had significantly higher in-hospital length of stay (6.0 days vs. 5.0 days, p < 0.0001) compared to controls. Study group patients also had higher incidence and odds of ninety-day medical and surgical complications (10.2% vs. 5.0%; OR, 2.50; 95% CI, 2.16–2.89; p < .0001). Moreover, patients with depressive disorders had significantly higher episode of care reimbursement ($54,539.2 vs. $51,645.2, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

This study illustrated that even after controlling for factors such as sex, age, and comorbidities, patients with depressive disorders had higher rates of in-hospital length of stay, medical and surgical complications, and total reimbursement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depressive disorder is defined as a culmination of symptoms including depressed mood or anhedonia, weight and/or appetite changes, fatigue, sleep disturbances, feelings of worthlessness, inability to concentrate, and/or suicidal ideation [1]. While there is now greater awareness about mental health issues such as depression, epidemiological trends show that the prevalence of depressive disorders will continue to increase in the United States as well as globally [2,3,4]. The World Health Organization has established major depression to be the third cause of worldwide burden of disease and predicts that by the year 2030, the disease will rank number one [5]. Additionally, increased rates of depressive disorders will inevitably lead to higher healthcare costs for patients [6,7,8,9]. Moreover, for patients undergoing complex surgical procedures, these soaring rates can have significant clinical implications due to the various manifestations of depressive disorder.

In recent years, there has been a noteworthy increase in the number of spinal procedures, such as lumbar fusion to correct spinal deformity [10]. This recent increase in spinal procedures coupled with the high rates of depressive disorders can pose significant challenges for spine surgeons. According to multiple studies, patients with preoperative depression experience significantly increased rates of postoperative complications and adverse effects following spine surgery [11,12,13,14]. However, a major limitation of the aforementioned studies is that they have small sample sizes with most having fewer than 200 study participants. Additionally, many of the current studies analyze multiple preoperative health conditions in a single study or lump together various spine surgeries rather than focusing on one specific procedure. For this reason, further research is needed to properly address the impact of depressive disorder on lumbar deformity surgery by using an adequately large sample size.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to analyze the impact of depressive disorder on patients undergoing lumbar deformity surgery and investigate whether they have higher rates of (1) in-hospital length of stay, (2) medical and surgical complications, and (3) total reimbursement.

Methods

Data source

A retrospective level III case–control study from January 1st, 2007 to December 31st, 2015 was performed using the Humana administrative claims database from the PearlDiver (PearlDiver Technologies, Fort Wayne, Indiana) supercomputer. The database contains the records of over 100 million patients from the Humana and Medicare administrative claims database. The Humana dataset was used for the study as it allowed to exclude pharmacological use and any adverse effects due to certain anti-depressant medications. Due to the large population of patients within the database, the supercomputer has been used extensively for spine related research and for other orthopaedic subspecialties. Information such as complications, diagnoses, costs, in-hospital length of stay, and other metrics are available from the supercomputer. Data from the supercomputer is extracted as a comma separated value (.csv) spreadsheet without patient identifiers. Since the database contains deidentified information, the study was exempt from our institution’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals (Table 1).

Study cohorts

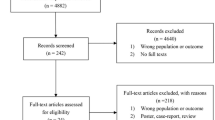

The inclusion criteria for the study group consisted of all patients undergoing lumbar deformity fusion with a diagnosis of depressive disorder. Patients without depressive disorder served as controls. The exclusion criteria consisted of all patients with the following conditions: traumatic fracture, pathologic fractures, or infections. A comprehensive list of codes used in the study can be found in Supplementary Table 1. The database was initially queried for all patients in the database undergoing primary lumbar fusion using International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) procedural codes 81.04 to 81.08. Patients undergoing fusion of 4 to 8 vertebral levels were filtered using ICD-9 procedural code 81.63. The study cohort was randomly matched to controls in a 1:2 ratio by age, sex, and medical comorbidities–chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity [body mass index (BMI > 30 kg/m2)], and tobacco use. In total, the query yielded 3706 patients, with 1286 who were experiencing symptoms of depressive disorders, and 2420 who served as the control cohort (Fig. 1).

Outcomes

Primary endpoints of the study were to compare in-hospital length of stay, ninety-day medical and surgical complications, and total global ninety-day episode of care costs. Ninety-day medical and surgical complications assessed included acute renal failure, cerebrovascular accidents, deep vein thromboses, dural tears, ileus, myocardial infarction, neurological complications, pneumonia, pulmonary emboli, respiratory failure, surgical site infections, and urinary tract infections. Ninety-day episode of care reimbursements were compared using reimbursement data from PearlDiver Mariner, which has been used in previously published studies as well.

Data analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the programming language R (R), Foundation for Computational Statistics; Vienna, Austria). Patient demographics of age, sex, and medical comorbidities were compared using Pearson’s chi-square analyses. Logistics regression analyses were used to calculate odds-ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) to assess the impact of depressive disorder on medical and surgical complications within ninety days following the index procedure. Since the continuous variables were not normally distributed, Mann–Whitney U test was used to test for significance for in-hospital length of stay and reimbursement between the matched cohorts. Due to the number of comparisons being made in the study and to reduce the probability of a type I error, Bonferroni adjusted corrections were performed. Thus, a p-value less than 0.003 was considered statistically significant. This was attained by dividing 0.05 by the total number of comparisons performed in the study (n = 13).

Results

In-hospital length of stay

The study found that patients with depressive disorders undergoing lumbar deformity fusion were found to have significantly higher in-hospital length of stay (6.0 days vs. 5.0 days, p < 0.0001) when compared to the control groups.

Ninety-day medical and surgical complications

Patients suffering from depressive disorders undergoing lumbar deformity fusion were discovered to have higher incidence and odds (10.2% vs. 5.0%; OR, 2.50; 95% CI, 2.16–2.89; P < 0.0001) of medical and surgical complications between ninety days following the spine procedure. More specifically, when compared to the control group, patients with depressive disorders had higher incidence and odds of developing respiratory failure (15.7% vs. 9.1%; OR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.82–2.99; P < 0.0001), myocardial infarction (4.0% vs. 1.2%; OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.38–3.66; P = 0.0001), and cerebrovascular accident (12.9% vs. 5.4%; OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.63–3.06; P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Other statistically significant complications are noted in Table 2.

Medical reimbursement

Compared to controls, patients with depressive disorders incurred substantially higher reimbursement. There was a statistically significant difference in the ninety-day episode of care reimbursement ($54,539.2 vs. $51,645.2, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Depressive Disorder is a prevailing and debilitating illness that dramatically impacts overall quality of life and surgical outcomes. Unfortunately, its prevalence is steadily increasing with at least one in five individuals suffering from depression in their lifetime [5]. This is also a serious public health issue as epidemiological trends show that the global burden of depression will continue to rise [15,16,17,18]. The World Health Organization estimates that 322 million people are battling against depression and that just in the years 2005 to 2015 alone, there was an 18.4% increase in the number of people living with depression [19]. With the advent of new technological innovations and surgical techniques, the rate of lumbar fusion procedures for spinal deformity have been increasing as well [20, 21]. However, despite the aforementioned trends, there is limited research analyzing the effects of depressive disorders on lumbar fusion outcomes. Our study demonstrated that patients with depressive disorders experience significantly longer in-hospital length of stay, increased ninety-day medical and surgical complications, and higher reimbursement.

The literature regarding depressive disorder is consistent with the findings of this study [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. For instance, patients with depressive disorders have higher in-hospital length of stay [22,23,24]. In a retrospective study of 5749 patients, Anastasio et al. analyzed the impact of depression and anxiety on in-hospital length of stay after patients underwent posterior spinal fusion [22]. Even after controlling for confounding variables and comorbidities, patients with depression had higher odds ratios for increased length of stay (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.08–1.26; P < 0.0001). These results were corroborated by a retrospective study by Krampe et al. which examined whether depression mediates effects of loneliness, social support, and living alone on in-hospital length of stay [23]. The study found that patients with depression had significantly longer length of stay when compared to controls (4.0 days vs. 3.0 days, p < 0.001). In contrast, in a retrospective study of 3759 patients, Elsamadicy et al. found that affective disorders amongst adolescents do not significantly impact surgical outcomes [24]. However, this is likely due to a smaller sample size; out of the 3759 total study participants, only 164 (4.4%) participants had an affective disorder, which is a limitation of the study.

In addition to longer in hospital length of stay, we found that patients with depression also have increased ninety-day medical and surgical complications after surgery. In a retrospective study conducted on 923 patients undergoing elective spine surgery, Elsamadicy et al. found that when compared to the control group, patients in the depression group had an approximate twofold increase in rates of postoperative delirium (10.6% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.01) [25]. In another retrospective study conducted on 70,581 patients who underwent lumbar spine surgery, Schoell et al. found that depression was a significant risk factor for a plethora of medical and surgical complications, such as dural tear (risk ratio, 1.2, p < 0.0001), damage to nervous tissue (risk ratio, 1.4, p < 0.0001), and failed back surgery syndrome (risk ratio, 1.7, p < 0.0001) [26]. These findings were further supported by a retrospective study conducted by Shah et al. using the Pearl Diver patient record database to explore whether patients with depression and/or anxiety undergoing posterior thoracolumbar spinal surgery had an increased risk of postoperative complications and reoperations [27]. Similar to our study, it was found that patients with depression and/or anxiety had significantly higher rates of infection (OR = 1.743, p = 0.022) and respiratory complications (OR = 1.492, p = 0.02) at the ninety-day postoperative period. We hypothesize patients with depressive disorders might have higher likelihood of medical complications due to patients with psychiatric illness having poor overall medical health compared to the baseline medical health of patients without a psychiatric illness before undergoing the procedure. This discrepancy could make certain patient populations more prone to adverse surgical outcomes. Another reason could be the reluctance of surgeons to operate on patients with psychiatric illnesses, which potentially leads to patients with only the most severe conditions getting invasive procedures done and thus overestimating the poor outcomes.

Our study results also revealed that there was a significant increase in the cost of care for patients with depressive disorder. This could partially be explained by the increased rates of medical and surgical complications and higher length of stay amongst patients with depression. These findings are also supported by similar studies conducted on patients with depression encountering various forms of spine pathology. In a retrospective cross-sectional analysis conducted on 37,094 patients, Ren et al. investigated the increased health care reimbursement for patients with depression undergoing treatment for spine pathology [28]. It was found that for spine patients with depression, the cost of treatment was 1.42 times more than cost of treatment for patients without depression (95% CI, 1.34–1.52; P < 0.001) and that this could translate to an additional $3500 annually. Similar findings were noted in another retrospective study conducted by O’Connell et al. on patients undergoing lumbar fusion [29]. The study utilized a national longitudinal administrative database which provides reimbursement information and diagnostic data in order to acquire one-year and two-year costs. One of the major findings of the study was that patients with preoperative depression faced increased health care reimbursement postoperatively at both the one-year and two-year mark (p < 0.001). This study reported an estimated $3024 increase in annual reimbursement for patients with depression, which also supports our results. It is also important to note that some of these additional reimbursement can be attributed to increased use of antidepressants amongst patients with depression [30].

Limitations

Despite the large sample size, our study is not without limitations. For instance, since we utilized a single insurance database, the cross-sectional analysis may not be generalizable and truly representative of patients with different insurances who are also suffering from depression and undergoing lumbar deformity fusion. Moreover, the study data is dependent on precise coding for procedural and diagnostic information in addition to patient identification. However, there is an estimated 1.3% rate of coding errors when using administrative databases [31]. Another factor that could impact study results is if patients in the control group were suffering from depression but were never formally diagnosed, which could lead to an underestimation of the impact of depression. In fact, even amongst patients who are diagnosed, there can be discrepancies due to inadequate management or lack of treatment. Moreover, the study’s retrospective nature can also be a limitation as it can introduce selection bias due to the study design. In addition, while the study controlled for factors such as sex, age, and comorbidities, there could be additional variables and comorbidities which could contribute to the study results. Additionally, variation in surgical procedure and protocol for lumbar fusion can potentially affect patient outcomes; however, this information was not provided by the database. Last but not least, while the study shows statistically significant differences in factors such as length of stay and reimbursement, these differences are not clinically as significant. Length of stay can also be impacted by various other factors such as patient proximity, invasiveness of the procedure, and availability of beds. Despite these limitations, this study is the first to analyze the impact of depressive disorder on patient outcomes following lumbar deformity fusion while controlling for factors like sex, age, and comorbidities.

Future directions

Moving forward, future studies can focus on treated and untreated depressive disorders in order to compare surgical outcomes of different patient populations based on the severity of symptoms and the level of treatment received. Another factor that can be analyzed is age of the patients because the impact of depressive disorders may differ between younger and older patient populations. Additionally, future research can be done comparing psychiatric conditions besides depressive disorders and their impact on surgical outcomes.

Conclusion

Ultimately, this study served to highlight the significant increase in length of stay, complications, and total reimbursements despite controlling for factors such as sex, age, and comorbidities for patients diagnosed with depressive disorders undergoing lumbar deformity fusion.

Abbreviations

- OR: :

-

Odds ration

References

Tolentino JC, Schmidt SL (2018) DSM-5 criteria and depression severity: implications for clinical practice. Front Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYT.2018.00450

Daly M, Sutin AR, Robinson E (2021) Depression reported by US adults in 2017–2018 and March and April 2020. J Affect Disord 278:131–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2020.09.065

Lu W (2019) Adolescent depression: national trends, risk factors, and healthcare disparities. Am J Health Behav 43(1):181–194. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.43.1.15

Todd M, Teitler J (2019) Darker days? Recent trends in depression disparities among US adults. American J Orthopsychiatry 89(6):735

Malhi GS, Mann JJ (2018) Depression. Lancet 392(10161):2299–2312. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31948-2

Sporinova B, Manns B, Tonelli M et al (2019) Association of mental health disorders with health care utilization and costs among adults with chronic disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2(8):199910. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9910

König H, König HH, Konnopka A (2019) The excess costs of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000180

Cronin KJ, Mair SD, Hawk GS et al (2020) Increased health care costs and opioid use in patients with anxiety and depression undergoing rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy 36(10):2655–2660. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ARTHRO.2020.05.038

Mausbach BT, Yeung P, Bos T et al (2018) Health care costs of depression in patients diagnosed with cancer. Psychooncology 27(7):1735–1741. https://doi.org/10.1002/PON.4716

Singh R, Moore ML, Hallak H et al (2002) Recent trends in medicare utilization and reimbursement for lumbar fusion procedures 2000–2019. World Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.05.131

Zhou Y, Deng J, Yang M et al (2021) Does the preoperative depression affect clinical outcomes in adults with following lumbar fusion?: A retrospective cohort study. Clin Spine Surg 34(4):E194–E199. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000001102

Doi T, Nakamoto H, Nakajima K et al (2019) Effect of depression and anxiety on health-related quality of life outcomes and patient satisfaction after surgery for cervical compressive myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 31(6):816–823. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.6.SPINE19569

Jiménez-Almonte JH, Hautala GS, Abbenhaus EJ et al (2020) Spine patients demystified: what are the predictive factors of poor surgical outcome in patients after elective cervical and lumbar spine surgery? Spine J 20(10):1529–1534. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SPINEE.2020.05.550

Divi SN, Goyal DK, Mangan JJ et al (2020) Are outcomes of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion influenced by presurgical depression symptoms on the mental component score of the short form-12 survey? Spine 45(3):201–207. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003231

Liu Q, He H, Yang J et al (2020) Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: findings from the global burden of disease study. J Psychiatr Res 126:134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPSYCHIRES.2019.08.002

Friedrich MJ (2017) Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA 317(15):1517. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2017.3826

Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Porras-Segovia A, Dunne H, Andrade-González N, Cervilla JA (2020) Prevalence and correlates of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Brazilian J Psychiatry 42:657–672. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0650

Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Martinez AM et al (2018) Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychol Med 48(8):1308–1315. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002781

World Health Organization (2017). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254610.

Reisener MJ, Pumberger M, Shue J et al (2020) Trends in lumbar spinal fusion-a literature review. J Spine Surg 6(4):752–776. https://doi.org/10.21037/JSS-20-492

Souslian FG, Patel PD (2021) Review and analysis of modern lumbar spinal fusion techniques. Br J Neurosurg Published online. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2021.1881041

Anastasio AT, Farley KX, Rhee JM (2020) Depression and anxiety as emerging contributors to increased hospital length of stay after posterior spinal fusion in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. North American Spine Soc J. 2:100012. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.XNSJ.2020.100012

Krampe H, Barth-Zoubairi A, Schnell T et al (2018) Social relationship factors, preoperative depression, and hospital length of stay in surgical patients. Int J Behav Med 25(6):658–668

Elsamadicy AA, Koo AB, Lee M et al (2019) Reduced influence of affective disorders on perioperative complication rates, length of hospital stay, and healthcare costs following spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Neurosurg Pediatr 24(6):722–727. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.7.PEDS19223

Elsamadicy AA, Adogwa O, Lydon E et al (2017) Depression as an independent predictor of postoperative delirium in spine deformity patients undergoing elective spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine 27(2):209–214. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.4.SPINE161012

Schoell K, Wang C, D’Oro A et al (2019) depression increases the rates of neurological complications and failed back surgery syndrome in patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery. Clin Spine Surg 32(2):E78–E85. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000000730

Shah I, Wang C, Jain N et al (2019) Postoperative complications in adult spinal deformity patients with a mental illness undergoing reconstructive thoracic or thoracolumbar spine surgery. Spine J 19(4):662–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SPINEE.2018.10.003

Ren BO, Khambete P, Rasendran C et al (2022) Quantifying the economic impact of depression for spine patients in the United States. Clin Spine Surg 35(3):E374–E379. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000001220

O’Connell C, Azad TD, Mittal V et al (2018) Preoperative depression, lumbar fusion, and opioid use: an assessment of postoperative prescription, quality, and economic outcomes. Neurosurg Focus. 44(1):E5. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.10.FOCUS17563

Sayadipour A, Kepler C, Mago R et al (2016) Economic effects of anti-depressant usage on elective lumbar fusion surgery - pubmed. Archiv Bone Joint Surg. 4(3):231–235

CMS. Medicare Fee-For-Service 2016 Improper Payments Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Medicare Fee-For-Service Improper Payments Report. Accessed July 20, 2022. www.cms.gov/cert,

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZJ made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. HP made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. LCV made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. ANR made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; also the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. JS made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; also the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AER made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; also the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. Drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study does not utilize any HPI and was exempt from IRB approval.

Informed consent

This is a database study and therefore did not require obtaining informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jamil, Z., Prior, H., Voyvodic, L.C. et al. A matched-control study on the impact of depressive disorders following lumbar fusion for adult spinal deformity: an analysis of a nationwide administrative database. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 34, 973–979 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-023-03719-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-023-03719-3