Abstract

Purpose

The core outcome measures index (COMI) is a validated multidimensional instrument for assessing patient-reported outcome in patients with back problems. The aim of the present study is to translate the COMI into Dutch and validate it for use in native Dutch speakers with low back pain.

Methods

The COMI was translated into Dutch following established guidelines and avoiding region-specific terminology. A total of 89 Dutch-speaking patients with low back pain were recruited from 8 centers, located in the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium. Patients completed a questionnaire booklet including the validated Dutch version of the Roland Morris disability questionnaire, EQ-5D, the WHOQoL-Bref, the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for pain, and the Dutch translation of the COMI. Two weeks later, patients completed the Dutch COMI translation again, with a transition scale assessing changes in their condition.

Results

The patterns of correlations between the individual COMI items and the validated reference questionnaires were comparable to those reported for other validated language versions of the COMI. The intraclass correlation for the COMI summary score was 0.90 (95% CI 0.84–0.94). It was 0.75 and 0.70 for the back and leg pain score, respectively. The minimum detectable change for the COMI summary score was 1.74. No significant differences were observed between repeated scores of individual COMI items or for the summary score.

Conclusion

The reproducibility of the Dutch translation of the COMI is comparable to that of other validated spine outcome measures. The COMI items correlate well with the established item-specific scores. The Dutch translation of the COMI, validated by this work, is a reliable and valuable tool for spine centers treating Dutch-speaking patients and can be used in registries and outcome studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Low back pain is a complex condition, affecting comfort as well as function and participation. It has been well recognized that assessment of outcomes from treatments should include patient-reported information captured by means of standardized questionnaires [1,2,3,4,5]. Deyo et al. and Mannion et al. have developed a tool consisting of the essential questions derived from the longer validated questionnaires, originally termed ‘the core set’ [5, 6]. At the same time, Ferrer et al. validated the originally core items proposed by Deyo et al. [7]. This work was further refined and resulted in The Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) [8, 9]. Hence, the COMI comprises a short set of questions suitable and validated for assessing the impact of spinal disorders on multiple patient-oriented outcome domains [8, 9].

The COMI was designed in the English language. Cross-cultural adaptations of the COMI were completed for several languages [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], and the COMI has become the main tool for the Spine Tango registry of EuroSpine, the Spine Society of Europe [18]. The purpose of the present paper is to make a cross-cultural adaptation of the COMI questionnaire for the Dutch-speaking patients in Belgium and The Netherlands, following established translation guidelines, and to validate this translation.

Materials and methods

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

The cross-cultural adaptation of the original English version of the COMI into Dutch was performed in accordance with the guidelines previously published by Beaton et al. [19].

Translation and synthesis

Two native Dutch-speaking Belgians (T-1, T-2) translated the COMI from English into Dutch independently from each other. T-1 was a native Dutch-speaking English teacher, not familiar with the concepts and the clinical content of the questionnaires. T-2 was a native Dutch-speaking orthopedic spine surgeon. Given that some differences in common vocabulary exist between The Netherlands and Flanders (i.e., the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium), they were instructed to avoid any words that might be interpreted differently by residents of both regions. Both translators compared their version and consensus was reached on a final common Dutch translation, T-12.

Back translation

Back-translations of T-12 into English were performed independently by a native English speaker with perfect understanding of Dutch and by a Dutch-speaking professor in English literature. Both back-translators were blind to the original English version, had no medical knowledge and were not familiar with the field.

Expert committee

An expert committee, consisting of both translators, both back-translators, as well as a neurosurgeon and orthopedic surgeon familiar with patient-reported outcome monitoring in spinal conditions, examined the translations and the back-translations and processed these into a pre-final version of the Dutch COMI. Again, special care was given to avoid any phrasing that might lead to different interpretations in The Netherlands and Flanders.

Test of the pre-final version (face validation)

Fifteen patients with LBP were asked to complete the pre-final version of the Dutch COMI, as well as to provide comments on how they understood the questions and any ambiguities perceived. Final adaptations based on these comments resulted in the final Dutch COMI version.

Assessment of the psychometric properties of the Dutch COMI version

Questionnaire battery

Two questionnaire booklets were composed. The first consisted of a set of sociodemographic variables (age, gender, LBP history, work status and type of work) as well as the final Dutch COMI translation and the validated Dutch translations of the Roland Morris disability questionnaire (RMQ) [20], the World Health Organization Quality of Life-Bref questionnaire (WHOQoL-Bref) [21], the EQ-5D [22] and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) measure of pain. The second booklet, supplied 2 weeks after completion of the first booklet, consisted of the final Dutch COMI translation and a 7-point Likert scale assessing any perceived change in low back condition over the previous 2 weeks.

Patients

89 patients were recruited from neurosurgical, orthopedic and physical medicine departments in 8 hospitals in Flanders. Patients with LBP with or without leg pain for more than 3 months were included. Exclusion criteria were: red flag situations (fracture, infection, cancer, inflammatory disease, neurological deficit, referred non-spinal pain), the potential for fast improvement or deterioration of back-related complaints and insufficient understanding of the Dutch language. The study was formally approved by the ethics committees of all eight involved hospitals. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Statistical analysis

No missing data were allowed for COMI, EQ-5D and NRS. For the WHOQoL and RMQ a minimum of 80% of filled questions was required for each domain/questionnaire [3, 20, 23]. If a response was missing in the latter questionnaires, the mean of the remaining responses was used.

Floor and ceiling effects were calculated as the proportion of individuals obtaining scores equivalent to the worst status and the best status, respectively, for each item and scale investigated. Floor/ceiling effects of 70% are considered to be adverse and effects of <10–15% are ideal [24, 25]. Floor and ceiling effects were determined for all scales in order to provide some perspective for interpreting the corresponding values for the COMI.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients were used to determine construct validity. We calculated the correlations between the COMI worst score of back and leg pain and the NRS score for overall pain, between COMI function and RMQ and WHOQoL-Bref physical health, between COMI symptom-specific well-being and WHOQoL-Bref physical health and WHOQoL-Bref whole score, between COMI quality of life and WHOQoL-Bref whole score and EQ-5D, between COMI disability and RMQ and WHOQoL-Bref physical health and finally between COMI summary score and RMQ, WHOQoL-Bref physical health and EQ-5D. Overall, in similar research, correlation values of >0.40 are considered satisfactory. For the present analysis satisfactory coefficients were expected for the relation between each item of the COMI and its corresponding full-length questionnaire. Since the validity of the translation is predominantly established by the extent to which similar patterns of correlations are observed for the comparison between COMI and reference questionnaires in Dutch as were observed in COMI validation studies in other languages, the present correlations are matched with correlations from the original validation study and the validation studies in French, Italian and Chinese.

One-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC; model ICC agreement 2,1; 2-way random). The ICC allows to quantify the agreement between two repeated measurements. An intra-class Correlation Coefficient of >0.70 in at least 50 patients is usually considered to represent sufficient reproducibility [26].

Standard errors of measurement (SEM) were employed to estimate the absolute measurement error and to calculate the minimum detectable change (MDC) for the tools used. In addition to producing an estimate of the standard deviation of errors, SEM allows for quantifying the extent to which a test provides accurate scores. The MDC is defined as 1.96 × √2 × SEM, equivalent to 2.77 × SEM [27].

SPSSv23 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used for making the statistical calculations.

Results

Cross-cultural adaptation of the COMI

The Dutch version of the COMI is presented in Appendix 1. As opposed to other validation studies in which often the phrasing ‘housework’ was interpreted as ‘actual work at home’ (programming, consultancy, etc.) instead of ‘work around the house (cleaning, dishes, etc.), we observed no problems with the interpretation of ‘huishoudelijke taken’ as the translation for ‘housework’. ‘Work outside the home’ was first translated to ‘buitenhuis werk’ and then translated back to ‘outdoor work’. Considering the fact that some people do some of their actual professional activities at home we agreed that the use of ‘job’ was the best option for the translation of ‘work outside the home’, ‘work’ and ‘job’, as it is commonly used in Dutch to indicate professional activity (both in Flanders as in The Netherlands).

Patients and data

Patient demographics and characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The data of all patients were used for the analyses of floor/ceiling effects and construct validity. All patients returned the second questionnaire within maximum 2 weeks after completing the first. Sixty-eight patients (76.4%) reported no or minimal change of their condition at 2 weeks. The data of these 68 patients were used to determine ICC. There were no missing data for COMI, EQ-5D, NRS and RMQ. For the WHOQoL there were no missing data exceeding 20%.

Floor and ceiling effects

The floor and ceiling effects for the individual COMI items are shown in Table 2. Acceptable floor effects were found for most COMI items. A rather high floor effect of 38.2% was observed for the COMI symptom-specific well-being and a high ceiling effect of 49.4% for the COMI work disability item. Neither floor nor ceiling effects were observed for the COMI summary score.

Construct validity

Correlations between the COMI items and reference questionnaires are summarized in Table 3. Overall satisfactory correlations were found. In addition, when comparing correlation coefficients between COMI and reference questionnaires from the present study with validation studies in other languages, relatively similar patterns were identified. The correlation between the COMI work disability item and the sociodemographic question about work status was also satisfactory.

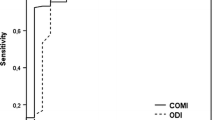

Test–retest reproducibility

The ICCs were 0.90 for the COMI summary score and 0.75 and 0.70 for the two pain scores (back and leg, respectively). The MDC for the COMI summary score was 1.74. The mean values of the COMI summary score were slightly lower in the 2 week assessment, but this difference was not significant (Table 4).

Discussion

As low back-related problems are multi-dimensional, patient-reported outcomes covering several outcome domains are of critical importance in assessing quality of care as well as in research in this field. The particular aim of the COMI was to include all domains considered relevant, i.e., pain, function, disease-specific well-being, overall quality of life and disability, in a concise and user-friendly, yet discriminative questionnaire. The COMI questionnaire is the cornerstone of Spine Tango, was validated on several occasions [7,8,9], and was recently found to be a responsive tool in spinal deformity surgery evaluation. [28]. Based on previous COMI studies, the estimated minimal clinically important difference for the COMI summary score is between 2 and 3 [9]. The minimum detectable change in the Dutch COMI summary score was 1.74. This means that for a change of 1.74 or more, there is a 95% likelihood that it is a result of the real change in the patient’s condition and not a measurement error. Similar values were reported for other language versions (French 1.98, German 1.74, Italian 1.51, Norwegian 2.21, Brazilian-Portuguese 1.66, Polish 1.79, Hungarian 1.63 [7,8,9,10, 12,13,14, 16]. The finding that the minimal clinically relevant difference for COMI exceeds the minimum detectable change (the noise) of the Dutch COMI version of 1.74 points, confirms its suitability as a LBP outcome measure instrument.

The cross-cultural adaptation of the English COMI version into Dutch was carried out carefully following established guidelines. While the Dutch language as it is used in The Netherlands and in Flanders differs in accent and is easily understandable across borders, some differences in vocabulary exist in spite of a huge overlap. Therefore, great care was given to avoid any phrasing that could lead to misinterpretation. We can state that ‘standard Dutch’ was used, which is the Dutch language officially taught and officially used by media and authorities in The Netherlands and Flanders, but also Suriname, Curaçao, Sint-Maarten, the Caribbean Netherlands and Aruba. A similar methodology was followed in the validation of the Dutch version of the Oswestry Disability Index [29]. No methodologist was involved in the adaptation process, which may be a limitation, as was the given that the second back-translator was not a native English speaker.

In general, the floor effects were low in the present study. The floor effects were higher for symptom-specific well-being, meaning that a relatively large proportion of patients considered their low back problems to affect their well-being to a considerable extent. A similar phenomenon was observed in the French cross-cultural adaptation, where, as opposed to other adaptations but similar to the present analysis, non-surgical patients were selected for the validation process [10]. The question referred to ‘having to live with the current complaint for the rest of life’. In the present study, 38.2% of the patients indicated that this would dissatisfy them to a large extent. This high floor effect in two non-surgical series as opposed to surgical cohorts in other cross-cultural adaptation studies might raise the question whether there could be a relation between the replies to this question and the perspective offered by the proposed therapy. A rather high ceiling effect (49.4%) was documented for the item work disability. As only 23.6% of the patients reported to be at work, this may seem odd. However, 25.8% responded to the work question as ‘not applicable’ because of retirement or unemployment and were not disabled. The sociodemographic work status question correlated well with the COMI work disability item after removing the N/A patients. Most patients were recruited from rehabilitation programs and not from surgical candidates, and therefore, a wide spectrum of severity was included. Yet, none of the floor/ceiling effect values exceeded 70%—the value considered adversely affecting the results. More importantly, in our mix of patients, sufficient construct validity was obtained, and patterns were observed that were highly comparable to the other cross-cultural adaptation analyses, as shown in Table 3. Overall, satisfactory correlations with full-length questionnaires were obtained. Of note, very good correlations between the Dutch version COMI summary score and the validated Dutch versions of RMQ, EQ-5D and WHOQOL-Bref were demonstrated. Also, the COMI summary score demonstrated excellent reproducibility, with an intraclass correlation being higher than that for the COMI back and leg pain scores.

We concluded from the analysis that the Dutch translation has acceptable psychometric properties and satisfactory reliability. As it was eventually brought to our attention through contacts with the developers of the original COMI (personal communication with Dr. A. Mannion) that correction of certain small inaccuracies would render the translation even closer to the original, the version published here is a very slightly amended one compared with the one used in the validation study. While these small adjustmentsFootnote 1 were considered unlikely to have a major impact on the overall validity of the instrument, it was considered a better strategy to amend the final version that will be recommended as the official Dutch version. As a consequence, the Dutch translation of the COMI presented here includes these changes, and we consider that it is suitable for widespread use in Dutch-speaking patients with low back-related problems in Belgium and The Netherlands.

Notes

Adjustments to validated Dutch translation: Q2: ‘Ergste pijn die ik mij kan voorstellen’ instead of ‘Ergste pijn die u zich kan voorstellen’; Q4: ‘Enigszins tevreden/ontevreden’ instead of ‘Tevreden/Ontevreden’; Q5: ‘Als u aan de afgelopen week terugdenkt, hoe zou u uw levenskwaliteit inschatten/beoordelen?’ instead of ‘Hoe zou u uw levenskwaliteit van de afgelopen week inschatten/beoordelen?’; Q7: ‘Hoeveel dagen van de laatste 4 weken heeft uw rugprobleem u belet om te werken?’ instead of ‘Hoeveel dagen van de laatste 4 weken kon u niet werken omwille van uw rugprobleem?’

References

Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, Buchbinder R (2010) The epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 24:769–781

Woolf AD, Pfleger B (2003) Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ 81:646–656

Mannion AF, Balague F, Pellise F, Cedraschi C (2007) Pain measurement in patients with low back pain. Nature Clin Pract Rheumatol 3:610–618

Resnik L, Dobrzykowski E (2003) Guide to outcomes measurement for patients with low back pain syndromes. J Orth Sports Phys Ther 33:307–316 (discussion 17-8)

Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B et al (1998) Outcome measures for low back pain research. A proposal for standardized use. Spine 23:2003–2013

Mannion AF, Elfering A, Staerkle R, Junge A, Grob D, Semmer NK et al (2005) Outcome assessment in low back pain: how low can you go? ESJ 14:1014–1026

Ferrer M, Pellise F, Escudero O, Alvarez L, Pont A, Alonso J, Deyo R (2006) Validation of a minimum outcome core set in the evaluation of patients with back pain. Spine 31:1372–1379 (discussion 1380)

Mannion AF, Porchet F, Kleinstuck FS, Lattig F, Jeszenszky D, Bartanusz V et al (2009) The quality of spine surgery from the patient’s perspective. Part 1: the core outcome measures index in clinical practice. ESJ 18(Suppl 3):S367–S373

Mannion P et al (2009) Minimal clinically important difference for improvement and deterioration as measured with the core outcome measures index. ESJ 18(Suppl 3):S374–S379

Mannion AF, Boneschi M, Teli M, Luca A, Zaina F, Negrini S et al (2012) Reliability and validity of the cross-culturally adapted Italian version of the core outcome measures index. ESJ 21(Suppl 6):S737–S749

Ferrer M, Pellise F, Escudero O, Alvarez L, Pont A, Alonso J et al (2006) Validation of a minimum outcome core set in the evaluation of patients with back pain. Spine 31:1372–1379 (discussion 1380)

Genevay S, Cedraschi C, Marty M, Rozenberg S, De Goumoens P, Faundez A et al (2012) Reliability and validity of the cross-culturally adapted French version of the core outcome measures index (COMI) in patients with low back pain. ESJ 21:130–137

Qiao J, Zhu F, Zhu Z, Xu L, Wang B, Yu Y et al (2013) Validation of the simplified Chinese version of the core outcome measures index (COMI). ESJ 22:2821–2826

Storheim K, Brox JI, Lochting I, Werner EL, Grotle M (2012) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Norwegian version of the core outcome measures index for low back pain. ESJ 21:2539–2549

Miekisiak G, Kollataj M, Dobrogowski J, Kloc W, Libionka W, Banach M et al (2013) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Polish version of the core outcome measures index for low back pain. ESJ 22:995–1001

Klemencsics I, Lazary A, Valasek T, Szoverfi Z, Bozsodi A, Eltes P et al (2016) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Hungarian version of the core outcome measures index for the back (COMI back). ESJ 25:257–264

Damasceno LH, Rocha PA, Barbosa ES, Barros CA, Canto FT, Defino HL et al (2012) Cross-cultural adaptation and assessment of the reliability and validity of the core outcome measures index (COMI) for the Brazilian-Portuguese language. ESJ 21:1273–1282

Roder C, Chavanne A, Mannion AF, Grob D, Aebi M (2005) SSE Spine Tango–content, workflow, set-up. www.eurospine.org-Spine Tango. ESJ 14:920–924

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB (2000) Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 25:3186–3191

Brouwer S, Kuijer W, Dijkstra PU, Goeken LN, Groothoff JW, Geertzen JH (2004) Reliability and stability of the Roland Morris disability questionnaire: intra class correlation and limits of agreement. Disabil Rehabil 26:162–165

Trompenaars FJ, Masthoff ED, Van Heck GL, Hodiamont PP, De Vries J (2005) Content validity, construct validity, and reliability of the WHOQoL-Bref in a population of Dutch adult psychiatric outpatients. Qual Life Res 14:151–160

EuroQol Group (2014) EQ-5D-3L official translation in Dutch for use in Belgium. http://www.euroqol.org/eq-5d-products/eq-5d-3l.html. Accessed 15 Jan 2016

The Whoqol Group (1998) The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQoL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 46:1569–1585

Hyland ME (2003) A brief guide to the selection of quality of life instrument. Health Qual Live Outcomes 1:24

McHorney CA, Tarlov AR (1995) Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res 4:293–307

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J et al (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidem 60:34–42

Bombardier C (2000) Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine 25:3100–3103

Mannion AF, Vila-Casademunt A, Domingo-Sàbat M, Wunderlin S, Pellisé F, Bago J, Acaroglu E, Alanay A, Pérez-Grueso FS, Obeid I, Kleinstück FS, European Spine Study Group (ESSG) (2016) The core outcome measures index (COMI) is a responsive instrument for assessing the outcome of treatment for adult spinal deformity. ESJ 25(8):2638–2648

van Hooff ML, Spruit M, Fairbank JC et al (2015) The oswestry disability index (version 2.1a): validation of a Dutch language version. Spine 40(2):pE83–pE90

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

There was no funding for this study and the authors declare to have no financial relations of any kind related to the subject of this study.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Van Lerbeirghe, J., Van Lerbeirghe, J., Van Schaeybroeck, P. et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Dutch version of the core outcome measures index for low back pain. Eur Spine J 27, 76–82 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5255-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5255-8