Abstract

Purpose

To summarise recommendations about 20 non-surgical interventions for recent onset (<12 weeks) non-specific low back pain (LBP) and lumbar radiculopathy (LR) based on two guidelines from the Danish Health Authority.

Methods

Two multidisciplinary working groups formulated recommendations based on the GRADE approach.

Results

Sixteen recommendations were based on evidence, and four on consensus. Management of LBP and LR should include information about prognosis, warning signs, and advise to remain active. If treatment is needed, the guidelines suggest using patient education, different types of supervised exercise, and manual therapy. The guidelines recommend against acupuncture, routine use of imaging, targeted treatment, extraforaminal glucocorticoid injection, paracetamol, NSAIDs, and opioids.

Conclusion

Recommendations are based on low to moderate quality evidence or on consensus, but are well aligned with recommendations from international guidelines. The guideline working groups recommend that research efforts in relation to all aspects of management of LBP and LR be intensified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

In 2012, the Danish Finance Act appropriated a total of €10.8 mio for the preparation of clinical guidelines. The Danish Health Authority (DHA) was subsequently commissioned to formulate 47 national clinical guidelines to support evidence-based decision making within health areas with a high burden of disease, a perceived large variation in practice, or uncertainty about which care was appropriate [1]. Two of these areas were low back pain (LBP) and lumbar radiculopathy (LR). Consequently in 2014, two working groups were formed with the aim of developing national clinical guidelines for non-surgical interventions for recent onset (<12 weeks) LBP and for recent onset (<12 weeks) LR. The primary target groups for these guidelines were primary sector healthcare providers, i.e., general practitioners, chiropractors, and physiotherapists, but also medical specialists or others in the primary or secondary healthcare sector handling patients with LBP or LR.

An estimated 15% of the Danish population suffers from low back pain (LBP) [2], and most will experience LBP during their lifetime [3], which is in accordance with estimates globally [4]. Both globally [5] and in Denmark [6], LBP with or without LR is a leading cause of years lived with disability, and consequently has major socioeconomic impact on society. For example, out of the 2.9 million Danes in the workforce, those with LBP have 5.5 million more days off work annually when compared to those without LBP, which accounts for 20% of all sick days, and LBP with or without LR is the most common reason for seeing a general practitioner, accounting for almost one in ten visits [2]. In addition, Danes with LBP visit their general practitioner 3.3 times more often compared to Danes without LBP, and they consult approximately 30% more often chiropractors and physiotherapists [2]. Once you have had an episode of LBP, most will experience recurrences [7], and only a minority will stay pain free for longer periods of time [8]. Additionally, 1–10% of patients with LBP will experience LR, which is associated with a poorer prognosis compared to LBP without LR [9].

This paper summarises the two Danish national clinical guidelines, which were published in 2016 as full reports in Danish [10, 11]. The mandates for the two working groups were to make recommendations based on a maximum of ten clinical questions for LBP and LR each. The working groups were not asked to make recommendations for diagnostic procedures or care pathways.

Methods

Study design

The guidelines were based on systematic reviews of the scientific literature and subsequent meta-analyses. The evidence of effect was balanced against the risk of harms and patient preferences to make recommendations related to each of the clinical questions. The method followed international standards for clinical guidelines [12], which were operationalised in a handbook from DHA [13] and briefly summarised below. This method was based on the Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [14]. The full clinical guidelines are available with all supportive material, including a description of the methods on the DHA webpage (in Danish) [13].

Organisation of the work

For each guideline, a project group within DHA consisting of a chairman, a project manager, a lead reviewer, a search specialist, a methodologist, and a multidisciplinary working group with 10 (LBP) and 12 (LR) members was set up. Working group members were appointed by invitation from professional organisations and scientific societies. They were involved in all parts of the process including formulating the clinical questions, selecting literature, data extraction, rating the quality of evidence, and formulating recommendations. Reference groups with representatives from stakeholders from the Danish healthcare system (municipalities, regions and hospitals), and patient organisations discussed and gave suggestions to the clinical questions and feedback on the recommendations. The lead reviewers coordinated the tasks of the working groups and drafted the reports. Potential conflicts of interest were declared by all involved partners and made publicly available on the DHA webpage (in Danish) [10, 11].

Finally, drafts of each of the clinical guidelines were in a public hearing and reviewed by two external peer-reviewers. The comments and feedback were considered by the working groups and taken into consideration when formulating the final versions of the guidelines.

Formulating the clinical questions

The clinical guidelines addressed a maximum of ten clinical questions, which were structured according to the Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome approach (PICO) framework [14].

Populations

The target populations were: (1) patients above the age of 16 years suffering from non-specific LBP with or without associated leg pain, but no signs of LR, and (2) patients with symptoms and clinical signs of LR above the age of 18 years. The symptoms had to have lasted less than 12 weeks for both populations. It was assumed that the differentiation between non-specific LBP and LR could be based on anamnestic information and a clinical examination without diagnostic imaging. Therefore, no distinction was made between LR caused by disc herniation and other degenerative conditions. Studies were eligible for the clinical guideline on LBP if at least 75% of the participants in a study matched the inclusion criteria. No such cut point was used in the LR guideline.

Interventions and comparisons

The mandate restricted the clinical guidelines to non-surgical interventions, and for the clinical guideline on LR only to non-pharmacological interventions. The choice of clinical questions was based on the working group’s perceived frequency of use, uncertainty about effectiveness, or uncertainty about whether one intervention was superior to another. Because it was assumed that all patients would receive basic information regarding disease progression, prognosis and danger signals, advice on activity and possible medical pain management when seeking care, it was decided to make recommendations about the interventions as a supplement or add-on to this basic treatment with no further specification, hereafter named ‘usual care’. Thus, trials were eligible for inclusion when usual care was provided in both the intervention and the control group, and the intervention in question was added in the intervention group. By doing so, the effects of adding the interventions to usual care were reviewed; if this was not possible, a comparison of treatments or sham-controlled trials was accepted. Some clinical questions addressed a head-to-head comparison of two interventions when it was assumed that clinicians often will choose between the two.

Outcome measures

For each of the clinical questions, two or more primary outcome measures and their timing were chosen a priori by the working groups. For most LBP questions, back pain intensity and back pain-related activity limitation were deemed primary outcomes. Back pain intensity, leg pain intensity, back pain-related activity limitation, and neurological deficits were considered primary outcome measures for the LR questions. For all outcome measures, the absolute differences between intervention and control groups on generally accepted and validated instruments such as a visual analogue scale (VAS), a numeric pain rating scale (NRS), Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) or Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) should be available. In the LBP guideline, the pharmacological questions also included as primary outcomes were serious adverse events. Secondary outcomes measures included fear-avoidance, work status, health-related quality of life, study drop outs, recurrence, and surgery rates.

The working groups defined minimally clinically relevant effects as a difference of 15 mm on a 100 mm on a VAS-scale, two points on an 11-point NRS, and 10 points on a 100-point scale of back pain-related disability [15].

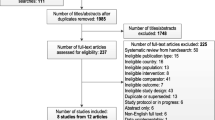

Literature searches and inclusion of literature

For each of the clinical questions, the literature was systematically searched in three-steps: Firstly, Embase, Medline, Cinahl (LBP only), Psycinfo (LBP only), PEDRO (LBP only) as well as national and international guideline databases were searched for clinical guidelines 10 years back (2004 and 2005 included, respectively, for LR and LBP). Secondly, Medline, Embase, Cinahl, PsycInfo, and Pedro (LBP only), and the Cochrane Library were searched for systematic reviews 10 years back, and thirdly, the same databases were searched for randomised clinical trials (RCTs) with no lower limit for publication year. In case a high-quality clinical guideline or systematic review would have covered earlier studies, the date for the last search for this review was used as the lower limit for the new search for randomised trials. All literature searches included studies published until and including December 2014 (LR) or March 2016 (LBP) published in English, German (LBP only), Norwegian, Swedish, or Danish. The search terms and strategies are available at the DHA website [10, 11].

Where no RCTs dealing with recent onset LR could be identified, indirect evidence from LR populations with symptoms lasting for more than 12 weeks informed consensus recommendations.

The lead reviewer screened and retrieved titles and abstracts. Potentially eligible papers were then collected in full text. Subsequently, the lead reviewer and a member of the working group independently screened the full text papers for inclusion or exclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The lead reviewer and a member of the working group or a scientific methods advisor independently extracted data for each clinical question and assessed all included papers for quality. If a high-quality clinical guideline or systematic review was available, data were extracted from these. The quality was assessed using the AGREE-II tool [16] for clinical guidelines, the AMSTAR tool [17] for systematic reviews, and the Cochrane risk of bias tool for RCTs [18]. When a risk of bias assessment was available from a Cochrane review, it was transferred directly to the clinical guideline. The handling of references and data extractions were performed using the web-based software Covidence [19], from which data were exported to the RevMan software [20] for meta-analyses; the results of which were further transferred to either GradePro [21] (LR) or MAGIC [22] (LBP) for GRADE assessment. Disagreements in data extraction and quality assessment were solved by consensus between the two evaluators in all instances. The quality of evidence was graded from very low to high according to the GRADE definitions (Table 1) for each outcome. Downgrading was done following standard definitions of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias [23]. The overall level of evidence supporting the recommendation for each clinical question was determined based on the quality for the primary outcome with the lowest quality evidence.

From evidence to recommendations

Finally, the evidence was summarised in evidence tables, and forest plots were constructed when meta-analyses were feasible. Based on the available evidence, strong or weak recommendations for or against an intervention were proposed following the criteria outlined in Table 2. Each recommendation was annotated with the strength of the recommendation and the level of evidence according to GRADE. In case no evidence was available from RCTs, a good practice recommendation was formulated based on clinical experience and consensus in the working group. The recommendations were based on weighing the quality of evidence, positive versus negative effects, patient values and preferences as well as the perception and experience of the working groups.

Results

The guidelines considered ten clinical questions concerning LBP and ten concerning LR. Six interventions were covered by both clinical guidelines, two of which were stand-alone interventions (advice to stay active vs rest; routine use of Magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] and/or X-ray vs. no imaging), and four were evaluated as an add-on to usual care vs. usual care (individualised patient information, supervised exercise, acupuncture, and manual therapy). In addition, the clinical guideline for LBP covered three questions addressing pharmacological interventions [paracetamol, opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)] as add-on to usual care, and targeted group-based care vs. non-targeted care. For LR, three head-to-head comparisons of exercise and manual therapy interventions (directional exercise vs. neuromuscular control training; directional exercise in combination with neuromuscular control training vs directional exercise alone; supervised exercises vs. manual therapy) were performed. An overview of the clinical questions and recommendations are provided in Table 3.

A short description of eligible papers, primary outcomes, recommendations, and levels of evidence are provided in Tables 4 and 5. Forest plots of all outcomes and risk of bias assessments are provided in Supplementary Appendix 1 and 2. Evidence tables are available in the complete clinical guidelines following each clinical question at the DHA website (in Danish) [10, 11].

Generally, recommendations from the two guidelines endorse patient enablement through information and education, advice to remain physically active and supervised exercise in addition to usual care. For pain relief, manual therapy including joint mobilisation and manipulation in addition to usual care was recommended, whereas the expert groups recommended only using pain medication in the form of paracetamol, NSAID, and opioids in addition to usual care after careful consideration in patients with LBP. No recommendations were made for the use of pain medication in relation to LR because this was outside of the mandate of the group.

Acupuncture was not endorsed for routine use in the two conditions. The groups recommended against routine imaging, i.e., X-ray or MRI, in patients presenting with both recent onset LBP and/or LR, and against the use of extraforaminal glucocorticoid injections in addition to usual care in patients with LR. Finally, it was recommended that patients with LR are referred for surgical consultation within 12 weeks if severe and disabling pain persists despite non-surgical treatment.

Of the 20 clinical questions, none could be answered by any of the clinical guidelines or systematic reviews that were retrieved. Recommendations were based on RCTs when available (16 out of 20 questions) and the remaining on professional consensus (four questions). Flow charts of included literature, quality assessments of clinical guidelines, systematic reviews, and RCTs and evidence tables are available at the DHA website (in Danish) [10, 11].

Discussion

Multidisciplinary expert groups formulated two national clinical guidelines for the DHA covering non-surgical treatment of recent onset LBP and LR in adults and found a striking lack of evidence for the effectiveness of the interventions examined. Thus, commonly used interventions like information and guidance, medication, mechanical diagnosis and therapy, massage, acupuncture, motor control exercise, and spinal manual therapy had either no or limited quality supporting evidence. Consequently, guideline recommendations are to a large extent based on consensus between members of the working groups; therefore, new high-quality trials focusing on LBP and LR patients are likely to impact future guideline recommendations greatly.

Wong et al. reviewed clinical practice guidelines for non-surgical management of LBP with or without LR published between 2005 and 2014 and found that advice and education about self-management and reassurance as well as advice for staying active, supervised exercise, and manual therapy were universally recommended for people presenting to health care professionals with these conditions [108]. They also found that paracetamol, and NSAID were recommended as treatment options in all guidelines reviewed, whereas muscle relaxants, and a short course of opioids were recommended in some but not all guidelines [108]. In 2016, new guidelines for non-invasive treatments for LBP and sciatica were published from The National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK [109]. These guidelines are more comprehensive than the Danish national guidelines because they also deal with chronic LBP, clinical examination and surgical treatments. However, for recent onset LBP and sciatica they also recommend providing people with advice and education as well as encouragement to stay active and continue with normal activities, to consider group exercises, and to consider manual therapy treatments as part of treatment that also include exercise [109]. With respect to pharmacological treatment, the NICE guidelines are similar to the Danish guidelines when they recommend against routine use of paracetamol as a stand-alone treatment, that NSAID is only to be used after careful consideration of co-morbidities and other risk-factors for side-effects and if used, then only in the lowest effective dose. Finally, they recommended that opioids should not be given routinely for managing LBP or sciatica [109].

Expert groups have used lack of evidence for benefit or harm for a particular intervention as an argument for not putting forward a recommendation [110]. Such interpretation of the evidence; however, has been met with frustration by health care professionals and professional societies who look to expert groups and task forces for guidance [111]. Fortunately, the GRADE methodology accommodates these circumstances as it classifies evidence as either strong or weak and provide interpretations for patients, clinicians, and policy makers [112]. Faced with either no or weak evidence, it is important that patients know that their particular preference among the various therapies should guide choice of intervention. Clinicians must, therefore, acknowledge that different choices may be appropriate for different patients and must help each patient choose a management option consistent with his or her values or preferences. Finally, policy makers must involve all relevant professional groups and stakeholders when determining how best to design care pathways [112]. Importantly, guideline panels should not refrain from making recommendations because individual patients and clinicians will make different choices when faced with a weak recommendation. In fact, this is to be expected. Consequently, the GRADE Working Group encourage panels to make recommendations wherever possible whether they are based on solid evidence or not [113].

Strengths of this national clinical guideline include the chairmanship by the DHA and the rigorous adherence to relevant scientific standards. Furthermore, the guideline working groups were composed of clinicians and academics with a range of professional backgrounds, as well as relevant professional societies and agencies were consulted during the process, which together aims to ensure buy-in by relevant stakeholders in the country. The guideline working groups were assisted by expert research librarians and guideline methodologists. Finally, the guidelines were peer-reviewed by international experts who provided detailed comments which resulted in revisions and clarifications prior to release of the final report. The main weakness of this work relates to the lack of clinical trials in some areas; therefore, the weak recommendations are mostly based on consensus in the guideline working groups. The DHA recommend that the guidelines are updated three years after the publication unless new developments warrant an earlier update.

Conclusion

Two multidisciplinary working groups developed two national clinical guidelines for non-surgical treatment in adult patients with LBP and LR of less than 12 weeks’ duration under the Danish Health Authority. The recommendations are based on limited evidence or on consensus, but are well aligned with recommendations from similar international guidelines. The guideline working groups strongly recommend that research efforts in relation to all aspects of the management of LBP and, in particular, LR be intensified.

References

Danish Health Authority. Mandate for Development of National Clinical Guidelines [In Danish]. 4-1013-10/1/SBRO. Denmark: Danish Health and Medicines Authority, 2012. https://www.sst.dk/da/sundhed/kvalitet-og-retningslinjer/~/media/EA5CFD60216C4DAA9102C21DF6C121D1.ashx

Flachs EM, Eriksen L, Koch MB, Ryd JT, Dibba E, Skov-Ettrup L, Juel K. The burden of disease in Denmark—Diseases [In Danish]. National Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark. Copenhagen: Danish Health Authority, 2015. https://www.sst.dk/da/sygdom-og-behandling/~/media/00C6825B11BD46F9B064536C6E7DFBA0.ashx

Danish Health Authority. Health of the Danish people—The national health profile 2013[In Danish]. Danish Health Authority, Copenhagen, 2014. https://www.sst.dk/~/media/1529A4BCF9C64905BAC650B6C45B72A5.ashx

Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F et al (2012) A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 64(6):2028–2037

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (2016) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388(10053):1545–1602

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C et al (2014) The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 73(6):968–974

Dunn KM, Hestbaek L, Cassidy JD (2013) Low back pain across the life course. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 27(5):591–600

Kongsted A, Kent P, Hestbaek L, Vach W (2015) Patients with low back pain had distinct clinical course patterns that were typically neither complete recovery nor constant pain. A latent class analysis of longitudinal data. Spine J 15(5):885–894

Konstantinou K, Hider SL, Jordan JL, Lewis M, Dunn KM, Hay EM (2013) The impact of low back-related leg pain on outcomes as compared with low back pain alone: a systematic review of the literature. Clin J Pain 29(7):644–654

Danish Health Authority. National Clinical Guideline: interventions for recent onset low back pain [in Danish]. 2016. https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2016/nkr-laenderygsmerter

Danish Health Authority. National Clinical Guideline: interventions for recent onset lumbar radiculopathy [in Danish]. 2016. https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2016/lumbal-nerverodspaavirkning-ikke-kirurgisk-behandling

Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F, Ollenschlager G, Phillips S, van der Wees P et al (2012) Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med 156(7):525–531

Danish Health Authority. Handbook of methodology: a model for conducting clinical guidelines [in Danish]. 2015. https://www.sst.dk/da/nkr/metode/metodehaandbog, 2017

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Atkins D, Brozek J, Vist G et al (2011) GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 64(4):395–400

Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, Waddell G, Croft P, Von Korff M et al (2008) Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33(1):90–94

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G et al (2010) AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol 63(12):1308–1311

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C et al (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 7:10

Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, vanTulder M, Editorial Board CBRG (2009) 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34(18):1929–1941

http://www.covidence.org. Accessed 18 Apr 2017

http://community.cochrane.org/tools/review-production-tools/revman-5. Accessed 18 Apr 2017

https://gradepro.org. Accessed 18 Apr 2017

https://www.magicapp.org. Accessed 18 Apr 2017

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, Rind D et al (2011) GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence-imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol 64(12):1283–1293

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J et al (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 64(4):401–406

Pengel LH, Refshauge KM, Maher CG, Nicholas MK, Herbert RD, McNair P (2007) Physiotherapist-directed exercise, advice, or both for subacute low back pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 146(11):787–796

Rozenberg S, Delval C, Rezvani Y, Olivieri-Apicella N, Kuntz JL, Legrand E et al (2002) Bed rest or normal activity for patients with acute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 27(14):1487–1493

Malmivaara A, Hakkinen U, Aro T, Heinrichs ML, Koskenniemi L, Kuosma E et al (1995) The treatment of acute low back pain–bed rest, exercises, or ordinary activity? N Engl J Med 332(6):351–355

Olaya-Contreras P, Styf J, Arvidsson D, Frennered K, Hansson T (2015) The effect of the stay active advice on physical activity and on the course of acute severe low back pain. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 7:19

Luijsterburg PA, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, van den Hoogen HJ, Peul WC, Avezaat CJ et al (2008) Physical therapy plus general practitioners’ care versus general practitioners’ care alone for sciatica: a randomised clinical trial with a 12-month follow-up. Eur Spine J 17(4):509–517

World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe (1998) Therapeutic patient education: continuing education programmes for health care providers in the field of prevention of chronic diseases: report of a WHO working group. Copenhagen

Traeger AC, Hubscher M, Henschke N, Moseley GL, Lee H, McAuley JH (2015) Effect of primary care-based education on reassurance in patients with acute low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 175(5):733–743

Hasenbring MI, Pincus T (2015) Effective reassurance in primary care of low back pain: what messages from clinicians are most beneficial at early stages? Clin J Pain 31(2):133–136

Damush TM, Weinberger M, Perkins SM, Rao JK, Tierney WM, Qi R et al (2003) The long-term effects of a self-management program for inner-city primary care patients with acute low back pain. Arch Intern Med 163(21):2632–2638

Jellema P, van der Windt DA, van der Horst HE, Twisk JW, Stalman WA, Bouter LM (2005) Should treatment of (sub)acute low back pain be aimed at psychosocial prognostic factors? Cluster randomised clinical trial in general practice. BMJ 331(7508):84

Indahl A, Velund L, Reikeraas O (1995) Good prognosis for low back pain when left untampered. A randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 20(4):473–477

Storheim K, Brox JI, Holm I, Koller AK, Bo K (2003) Intensive group training versus cognitive intervention in sub-acute low back pain: short-term results of a single-blind randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med 35(3):132–140

Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Pohjolainen T, Hurri H, Mutanen P, Rissanen P et al (2003) Mini-intervention for subacute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 28(6):533–540 (discussion 40-1)

Hay EM, Mullis R, Lewis M, Vohora K, Main CJ, Watson P et al (2005) Comparison of physical treatments versus a brief pain-management programme for back pain in primary care: a randomised clinical trial in physiotherapy practice. Lancet 365(9476):2024–2030

Gohner W, Schlicht W (2006) Preventing chronic back pain: evaluation of a theory-based cognitive-behavioural training programme for patients with subacute back pain. Patient Educ Couns 64(1–3):87–95

Hagen EM, Grasdal A, Eriksen HR (2003) Does early intervention with a light mobilization program reduce long-term sick leave for low back pain: a 3-year follow-up study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 28(20):2309–2315 (discussion 16)

Childs JD, Fritz JM, Flynn TW, Irrgang JJ, Johnson KK, Majkowski GR et al (2004) A clinical prediction rule to identify patients with low back pain most likely to benefit from spinal manipulation: a validation study. Ann Intern Med 141(12):920–928

Brennan GP, Fritz JM, Hunter SJ, Thackeray A, Delitto A, Erhard RE (2006) Identifying subgroups of patients with acute/subacute “nonspecific” low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31(6):623–631

Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, Herbert RD, McAuley JH (2008) Independent evaluation of a clinical prediction rule for spinal manipulative therapy: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J 17(7):936–943

Rabin A, Shashua A, Pizem K, Dickstein R, Dar G (2014) A clinical prediction rule to identify patients with low back pain who are likely to experience short-term success following lumbar stabilization exercises: a randomized controlled validation study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 44(1):6-B13

Klaber Moffett JA, Carr J, Howarth E (2004) High fear-avoiders of physical activity benefit from an exercise program for patients with back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 29(11):1167–1172

Ash LM, Modic MT, Obuchowski NA, Ross JS, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Grooff PN (2008) Effects of diagnostic information, per se, on patient outcomes in acute radiculopathy and low back pain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29(6):1098–1103

Gilbert FJ, Grant AM, Gillan MG, Vale L, Scott NW, Campbell MK et al (2004) Does early imaging influence management and improve outcome in patients with low back pain? A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 8(17):iii, 1–131

Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, Miller P, Kerslake R, Pringle M (2001) The role of radiography in primary care patients with low back pain of at least 6 weeks duration: a randomised (unblinded) controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 5(30):1–69

Kerry S, Hilton S, Dundas D, Rink E, Oakeshott P (2002) Radiography for low back pain: a randomised controlled trial and observational study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 52(479):469–474

Cruser A, Maurer D, Hensel K, Brown SK, White K, Stoll ST (2012) A randomized, controlled trial of osteopathic manipulative treatment for acute low back pain in active duty military personnel. J Man Manip Ther. 20(1):5–15

Hsieh CY, Adams AH, Tobis J, Hong CZ, Danielson C, Platt K et al (2002) Effectiveness of four conservative treatments for subacute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 27(11):1142–1148

Hurley DA, McDonough SM, Dempster M, Moore AP, Baxter GD (2004) A randomized clinical trial of manipulative therapy and interferential therapy for acute low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 29(20):2207–2216

Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, McLachlan AJ, Cooper CW, Day RO et al (2007) Assessment of diclofenac or spinal manipulative therapy, or both, in addition to recommended first-line treatment for acute low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 370(9599):1638–1643

Faas A, Chavannes AW, van Eijk JT, Gubbels JW (1993) A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exercise therapy in patients with acute low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 18(11):1388–1395

Faas A, van Eijk JT, Chavannes AW, Gubbels JW (1995) A randomized trial of exercise therapy in patients with acute low back pain. Efficacy on sickness absence. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 20(8):941–947

Seferlis T, Nemeth G, Carlsson AM, Gillstrom P (1998) Conservative treatment in patients sick-listed for acute low-back pain: a prospective randomised study with 12 months’ follow-up. Eur Spine J 7(6):461–470

Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Battie M, Street J, Barlow W (1998) A comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for the treatment of patients with low back pain. N Engl J Med 339(15):1021–1029

Chok B, Lee R, Latimer J, Tan SB (1999) Endurance training of the trunk extensor muscles in people with subacute low back pain. Phys Ther 79(11):1032–1042

Machado LA, Maher CG, Herbert RD, Clare H, McAuley JH (2010) The effectiveness of the McKenzie method in addition to first-line care for acute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 8:10

Liu JL, Li N (2010) Clinical observation of a combination of acupuncture and drug administration for non-specific acute lumbar sprain. J Acupunct Tuina Sci 8(1):47–49

Kennedy S, Baxter GD, Kerr DP, Bradbury I, Park J, McDonough SM (2008) Acupuncture for acute non-specific low back pain: a pilot randomised non-penetrating sham controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 16(3):139–146

Williams CM, Maher CG, Latimer J, McLachlan AJ, Hancock MJ, Day RO et al (2014) Efficacy of paracetamol for acute low-back pain: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 384(9954):1586–1596

Friedman BW, Dym AA, Davitt M, Holden L, Solorzano C, Esses D et al (2015) Naproxen with cyclobenzaprine, oxycodone/acetaminophen, or placebo for treating acute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314(15):1572–1580

Hofstee DJ, Gijtenbeek JM, Hoogland PH, van Houwelingen HC, Kloet A, Lotters F et al (2002) Westeinde sciatica trial: randomized controlled study of bed rest and physiotherapy for acute sciatica. J Neurosurg 96(1 Suppl):45–49

Vroomen PC, de Krom MC, Wilmink JT, Kester AD, Knottnerus JA (1999) Lack of effectiveness of bed rest for sciatica. N Engl J Med 340(6):418–423

Bakhtiary AH, Safavi-Farokhi Z, Rezasoltani A (2005) Lumbar stabilizing exercises improve activities of daily living in patients with lumbar disc herniation. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 18(3–4):55–60

Paatelma M, Kilpikoski S, Simonen R, Heinonen A, Alen M, Videman T (2008) Orthopaedic manual therapy, McKenzie method or advice only for low back pain in working adults: a randomized controlled trial with one year follow-up. J Rehabil Med 40(10):858–863

Huber J, Lisinski P, Samborski W, Wytrazek M (2011) The effect of early isometric exercises on clinical and neurophysiological parameters in patients with sciatica: An interventional randomized single-blinded study. Isokinet Exerc Sci 19(3):207–214

Albert HB, Manniche C (2012) The efficacy of systematic active conservative treatment for patients with severe sciatica: a single-blind, randomized, clinical, controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 37(7):531–542

Ye C, Ren J, Zhang J, Wang C, Liu Z, Li F et al (2015) Comparison of lumbar spine stabilization exercise versus general exercise in young male patients with lumbar disc herniation after 1 year of follow-up. Int J Clin Exp Med 8(6):9869–9875

Machado LA, de Souza M, Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML (2006) The McKenzie method for low back pain: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis approach. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31(9):E254–E262

Santilli V, Beghi E, Finucci S (2006) Chiropractic manipulation in the treatment of acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion: a randomized double-blind clinical trial of active and simulated spinal manipulations. Spine J 6(2):131–137

Bronfort G, Hondras MA, Schulz CA, Evans RL, Long CR, Grimm R (2014) Spinal manipulation and home exercise with advice for subacute and chronic back-related leg pain: a trial with adaptive allocation. Ann Intern Med 161(6):381–391

Petersen T, Larsen K, Nordsteen J, Olsen S, Fournier G, Jacobsen S (2011) The McKenzie method compared with manipulation when used adjunctive to information and advice in low back pain patients presenting with centralization or peripheralization: A randomized controlled trial. Spine 36(24):1999–2010

Furlan AD, Yazdi F, Tsertsvadze A, Gross A, Van Tulder M, Santaguida L et al (2012) A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of selected complementary and alternative medicine for neck and low-back pain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012:953139

Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC, Tsukayama H, Lao L, Koes BW et al (2005) Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD001351

Webster BS, Bauer AZ, Choi Y, Cifuentes M, Pransky GS (2013) Iatrogenic consequences of early magnetic resonance imaging in acute, work-related, disabling low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38(22):1939–1946

Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, Fu R, Bougatsos C, Dana T et al (2015) Epidural corticosteroid injections for radiculopathy and spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 163(5):373–381

Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, Fu R, Dana T, Sullivan S et al (2015) Pain management injection therapies for low back pain. US: Rockville, Maryland: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Contract No.: Report

Kolsi I, Delecrin J, Berthelot JM, Thomas L, Prost A, Maugars Y (2000) Efficacy of nerve root versus interspinous injections of glucocorticoids in the treatment of disk-related sciatica. A pilot, prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Joint Bone Spine. 67(2):113–118

Arden NK, Price C, Reading I, Stubbing J, Hazelgrove J, Dunne C et al (2005) A multicentre randomized controlled trial of epidural corticosteroid injections for sciatica: the WEST study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 44(11):1399–1406

Buchner M, Zeifang F, Brocai DR, Schiltenwolf M (2000) Epidural corticosteroid injection in the conservative management of sciatica. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 375(375):149–156

Bush K, Hillier S (1991) A controlled study of caudal epidural injections of triamcinolone plus procaine for the management of intractable sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 16(5):572–575

Carette S, Leclaire R, Marcoux S, Morin F, Blaise GA, St-Pierre A et al (1997) Epidural corticosteroid injections for sciatica due to herniated nucleus pulposus. N Engl J Med 336(23):1634–1640

Cohen SP, Gupta A, Strassels SA, Christo PJ, Erdek MA, Griffith SR et al (2012) Effect of MRI on treatment results or decision making in patients with lumbosacral radiculopathy referred for epidural steroid injections: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 172(2):134–142

Cohen SP, White RL, Kurihara C, Larkin TM, Chang A, Griffith SR et al (2012) Epidural steroids, etanercept, or saline in subacute sciatica: a multicenter, randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 156(8):551–559

Cuckler JM, Bernini PA, Wiesel SW, Booth RE Jr, Rothman RH, Pickens GT (1985) The use of epidural steroids in the treatment of lumbar radicular pain. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 67(1):63–66

Datta R, Upadhyay KK (2011) A randomized clinical trial of three different steroid agents for treatment of low backache through the caudal route. Med J Armed Forces India 67(1):25–33

el Zahaar MS (1991) The value of caudal epidural steroids in the treatment of lumbar neural compression syndromes. J Neurol Orthop Med Surg 12:181–184

Ghahreman A, Ferch R, Bogduk N (2010) The efficacy of transforaminal injection of steroids for the treatment of lumbar radicular pain. Pain Med 11(8):1149–1168

Helliwell M, Robertson JC, Ellis RM (1985) Outpatient treatment of low-back pain and sciatica by a single extradural corticosteroid injection. Brit J Clin Pract. 39(6):228–231

Iversen T, Solberg TK, Romner B, Wilsgaard T, Twisk J, Anke A et al (2011) Effect of caudal epidural steroid or saline injection in chronic lumbar radiculopathy: multicentre, blinded, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 343:d5278

Karppinen J, Malmivaara A, Kurunlahti M, Kyllonen E, Pienimaki T, Nieminen P et al (2001) Periradicular infiltration for sciatica: a randomized controlled trial. Spine 26(9):1059–1067

Klenerman L, Greenwood R, Davenport HT, White DC, Peskett S (1984) Lumbar epidural injections in the treatment of sciatica. Br J Rheumatol 23(1):35–38

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Cash KA, Pampati V, Damron KS, Boswell MV (2012) Effect of fluoroscopically guided caudal epidural steroid or local anesthetic injections in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation and radiculitis: a randomized, controlled, double blind trial with a two-year follow-up. Pain Physician 15(4):273–286

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Cash KA, Pampati V, Falco FJ (2014) A randomized, double-blind, active-control trial of the effectiveness of lumbar interlaminar epidural injections in disc herniation. Pain Physician 17(1):E61–E74

Mathews JA, Mills SB, Jenkins VM, Grimes SM, Morkel MJ, Mathews W et al (1987) Back pain and sciatica: controlled trials of manipulation, traction, sclerosant and epidural injections. Br J Rheumatol 26(6):416–423

Riew KD, Park JB, Cho YS, Gilula L, Patel A, Lenke LG et al (2006) Nerve root blocks in the treatment of lumbar radicular pain. A minimum five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88(8):1722–1725

Rogers P, Nash T, Schiller D, Norman J (1992) Epidural steroids for sciatica. Pain Clin 5:67–72

Sayegh FE, Kenanidis EI, Papavasiliou KA, Potoupnis ME, Kirkos JM, Kapetanos GA (2009) Efficacy of steroid and nonsteroid caudal epidural injections for low back pain and sciatica: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34(14):1441–1447

Snoek W, Weber H, Jorgensen B (1977) Double blind evaluation of extradural methyl prednisolone for herniated lumbar discs. Acta Orthop Scand 48(6):635–641

Tafazal S, Ng L, Chaudhary N, Sell P (2009) Corticosteroids in peri-radicular infiltration for radicular pain: a randomised double blind controlled trial. One year results and subgroup analysis. Eur Spine J 18(8):1220–1225

Valat JP, Giraudeau B, Rozenberg S, Goupille P, Bourgeois P, Micheau-Beaugendre V et al (2003) Epidural corticosteroid injections for sciatica: a randomised, double blind, controlled clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis 62(7):639–643

Wilson-MacDonald J, Burt G, Griffin D, Glynn C (2005) Epidural steroid injection for nerve root compression. A randomised, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br 87(3):352–355

Sabnis AB, Diwan AD (2014) The timing of surgery in lumbar disc prolapse: A systematic review. Indian J Orthop 48(2):127–135

Peul WC, van den Hout WB, Brand R, Thomeer RT, Koes BW, Leiden-The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study G (2008) Prolonged conservative care versus early surgery in patients with sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation: two year results of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 336(7657):1355–1358

Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson AN, Hanscom B, Skinner JS et al (2006) Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA 296(20):2441–2450

Wong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, Randhawa K, Yu H, Varatharajan S et al (2016) Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: a systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Eur J Pain 21(2):201–216

National Institute for Health Care Excellence (2016) Low back pain and sciatica: management of non-specific low back pain and sciatica. National Institute for health Care Excellence, London

Preventive US (2009) Services Task Force. Screening for skin cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 150(3):188–193

Petitti DB, Teutsch SM, Barton MB, Sawaya GF, Ockene JK, DeWitt T et al (2009) Update on the methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: insufficient evidence. Ann Intern Med 150(3):199–205

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Vist GE, Liberati A et al (2008) Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ 336(7652):1049–1051

Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y et al (2013) GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 66(7):719–725

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Kirsten Birkefoss, Marina T. Axelsen, and Hanne Caspersen, research librarians at the Danish Health Authority; Christine Marie Bækø Halling, project manager at the Danish Health Authority; Helle Ulrichsen, chairman of the LBP working group, and Karsten Junker, chairman of LR working group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Funding was provided by The Danish Finance Act (2012), and the DHA was commissioned to formulate the national clinical guidelines. Funding was provided to members of the project groups, i.e. lead reviewers (MJS and PK), project manager (BH), methodologists (JA and ST), search specialists, and chairmen. No funding was provided to the working or reference group members. The funders had no role in the design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflicts of interest

Potential conflicts of interest have been declared by all involved partners and made publicly available on the DHA webpage (in Danish) [10, 11].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stochkendahl, M.J., Kjaer, P., Hartvigsen, J. et al. National Clinical Guidelines for non-surgical treatment of patients with recent onset low back pain or lumbar radiculopathy. Eur Spine J 27, 60–75 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5099-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5099-2