Abstract

Well’s syndrome, in many circumstances, is determined by intensive eosinophilic infiltration into dermal layer with the clinical presentation of erythematous and edematous plaques which can easily be remitted by current corticosteroid therapies. Up to now, different etiologies have been proposed governing Well’s pathophysiological procedure. Of note, no evidence of seasonal association has been already reported. A 70-years-old afebrile male presented with a chief complaint of 30-years history of cutaneous manifestations along with non-ulcerated edematous, erythematous plaques and patches, and extensive pruritus confined on both dorsal and palmar surface of upper extremities occurred annually in early summer. We hereby report a case in season-dependent of Well’s syndrome occurrence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Well’s syndrome was first described by Sir George Wells in 1971, nominated by different terms such as “recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia” or “eosinophilic cellulitis,” driven by unknown etiology (Wells 1971). Up to date, a few cases have however been seen through the world (Tugnet et al. 2012). Common and more prominent clinical characteristics relevant to Well’s syndrome include a pruritic, erythematous, and edematous rashes or plaques resemble urticaria or cellulitis, although it has a similar appearance of bacterial cellulitis (Powell et al. 2012). Two consequent clinical phases have distinctively been notified through the progression of eosinophilic cellulitis; a primary symptom of pain and burning followed by plaques extend centrifugally. Thereafter, the plagues undergo the second stage which starts 1 to 3 weeks after plague formation leaving post-inflammatory changes which are characterized by noticeable dermal infiltrate of eosinophil and simultaneous scattered flame-like figures (Powell et al. 2012). Different mechanisms and stimuli have been proposed to participate in pathophysiology procedure of Well’s syndrome. For example, insect bites by arthropods and bee, thimerosal-contained vaccines cases were also reported previously (Schorr et al. 1984; Wood et al. 1986). Moreover, viral-, bacterial-, parasitic-, and antibiotic-associated cases were also resulted at the center of triggering events with a distinctive eosinophilic reaction (Calvert et al. 2006; Koh et al. 2003; Reichel et al. 1991; Toulon et al. 2007). Tugnet et al. announced two cases of anti-TNF treatment by adalumimab (Tugnet et al. 2012). The eosinophilic reaction has been seen at cutaneous plagues occurred simultaneously by an elevated level of serum interleukin 5 (IL-5), immunoglobulin E (IgE) and eosinophilia response utmost in over than 50 % affected individuals (EspaÑA et al. 1999; Powell et al. 2012). Some authorities declared that elevated IL-5 levels recruit eosinophils into site of cellulitis which in turn contribute to eosinophilic degranulation and consequent cutaneous destruction orchestrated by an eosinophil-derived cationic protein, ribonuclease enzyme (Gilliam et al. 2005). Up to present time, though different modalities have been exploited to treat Well’s syndrome, a variable prosperity was not achieved until yet (Sinno et al. 2012). Therefore, it was necessitated to perform an extensive workup, para-clinical examination, and cellular and molecular assessment to reveal underlying mechanisms participating in Well’s syndrome. To our knowledge, no seasonal relationship of Well’s syndrome cases was reported previously. Here, we represent a patient with seasonal relapsing of Well’s syndrome-related clinical signs.

Case history

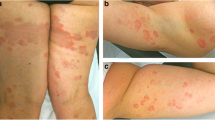

A healthy 70-years-old afebrile male presented to our clinic at Sina teaching hospitals affiliated to Tabriz University of Medical Sciences with a chief complaint of 30-year history of cutaneous manifestations of non-ulcerated edematous, erythematous plaques, and patches coinciding with extensive pruritus and sting which was confined on either dorsal or palmar surface of upper extremities (Fig. 1a). It occurred annually in early summer, but dramatically, around June to July. These cutaneous involvement, lasted for a period of 4–8 weeks, remitted after receiving intramuscular corticosteroid therapy (including prednisolone and dexamethasone) within 24–48 h and relapsed subsequently after a year vernally. Of note, no symptom of hypo-, hyperpigmentation, or scar tissue was developed post-corticosteroids administration (Fig. 1b). The patient had no history of other diseases unless mild hypertension and type II diabetes mellitus admitted for captopril and metformin. The patient has been working at grocery store and had no clues towards of any insect bite, sting, viral, or bacterial infection upon on local or systemic levels.

Pathological finding

A punch biopsy of lesion was performed with written informed consent obtained from patient. This study was approved by the local ethic committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and ethical principles of declaration of Helsinki. Histopathological examination revealed a severe edema in the papillary dermis. Dense interstitial inflammatory infiltration of large number of granulocytes, predominantly eosinophils and neutrophils with leukocytoclasis was evident in mid and deep dermis layers (Fig. 2a). Lymphocyte extravasation at perivascular areas as well as panniculitis without epidermal layer involvement was also evident indicating Well’s syndrome pattern (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, a low number of flame structures consisting of eosinophils entrapped in collagen fiber bundles was described (Fig. 2b).

a–c Low and high power photomicrograph of dense infiltration of inflammatory cell, particularly eosinophils within the dermis. a A severe edema was evident in the papillary dermis (asterisks). b Active cellular extravasation (black arrow heads) and flame figure (black arrows) structures are indicative for Well’s syndrome. c The most abundant cell type that was found infiltrated into the dermis included neutrophils and mainly eosinophils

In summary, Well’s syndrome, nominated as an eosinophilic cellulitis, has unknown etiology with a few cases reported until now. Here, we described a seasonal dependent occurrence of Well’s syndrome. It seems that a large body of documents collected by previous studies focused on multiple predisposing factors, unless seasonal, which prone cutaneous tissue to aforementioned syndrome. We here notified that even seasonal changes have important effect on Well’s remitting and relapsing procedure.

References

Calvert J, Shors AR, Hornung RL, Poorsattar SP, Sidbury R (2006) Relapse of Wells’ syndrome in a child after tetanus-diphtheria immunization. J Am Acad Dermatol 54(5 Suppl):S232–S233

España A, Sanz ML, Sola J, Gil P (1999) Wells’ syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): correlation between clinical activity, eosinophil levels, eosinophil cation protein and interleukin-5. Br J Dermatol 140(1):127–130

Gilliam AE, Bruckner AL, Howard RM, Lee BP, Wu S, Frieden IJ (2005) Bullous “cellulitis” with eosinophilia: case report and review of Wells’ syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics 116(1):e149–e155

Koh KJ, Warren L, Moore L, James C, Thompson GN (2003) Wells’ syndrome following thiomersal‐containing vaccinations. Australas J Dermatol 44(3):199–202

Powell JG, Ramsdell A, Rothman IL (2012) Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome) in a pediatric patient: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis 89(4):191–194

Reichel M, Isseroff R, Vogt P, Gandour‐Edwards R (1991) Wells’ syndrome in children: varicella infection as a precipitating event. Br J Dermatol 124(2):187–190

Schorr WF, Tauscheck AL, Dickson KB, Melski JW (1984) Eosinophilie cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome): histologic and clinical features in arthropod bite reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol 11(6):1043–1049

Sinno H, Lacroix J-P, Lee J, Izadpanah A, Borsuk R, Watters K, Gilardino M (2012) Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome): a case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg 20(2):91–97

Toulon A, Bourdon-Lanoy E, Hamel D, Fraitag S, Leruez-Ville M, de Prost Y, Hadj-Rabia S (2007) Wells’ syndrome after primoinfection by parvovirus B19 in a child. J Am Acad Dermatol 56(2 Suppl):S50–S51

Tugnet N, Youssef A, Whallett AJ (2012) Wells’ syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis) secondary to infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51(1):195–196

Wells G (1971) Recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc 57(1):46–56

Wood C, Miller AC, Jacobs A, Hart R, Nickoloff BJ (1986) Eosinophilic infiltration with flame figures a distinctive tissue reaction seen in Wells’ syndrome and other diseases. Am J Dermatopathol 8(3):186–193

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Additional information

Mohammad Reza Ranjkesh and Reza Rahbarghazi contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mokhtari, F., Rezabakhsh, A., Cheraghi, O. et al. The seasonal occurrence of Well’s syndrome. Comp Clin Pathol 25, 479–481 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-015-2220-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-015-2220-y