Abstract

Integrated reporting, the latest attempt to overcome the shortcomings of financial and sustainability reporting, has fast emerged as a new accounting practice. Recently, however, the integrated reporting movement has lost some of its momentum and is increasingly the subject of heated debate and controversy. In the related academic discourse, numerous scholars have started to question and challenge this new reporting trend from diverse angles. Against this backdrop, the present article reviews the current state of the academic literature to identify the major lines of criticism. Our findings show that the central critique relates to the fundamental concepts and guiding principles of the integrated reporting framework as well as to the International Integrated Reporting Council itself. By carving out the pivotal problem areas of integrated reporting, we identify critical issues that likely need to be addressed before integrated reporting can be expected to stand the test of time. We further identify three priority areas of criticism and discuss the attribution of responsibilities as well as approaches that offer potential solutions within these areas. Practitioners are invited to build upon our findings as potential intervention points for promoting the future acceptance and dissemination of integrated reports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The landscape of corporate reporting practice is in a constant state of flux. One underlying driver of change stems from the growing awareness that neither traditional financial nor sustainability reporting truly satisfies the information needs of diverse stakeholder groups (Atkins et al. 2015; Cohen et al. 2012; Fasan and Mio 2017). In response to related concerns, the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) advocates the integration of financial and non-financial information to provide a more holistic perspective of an organization’s value creation and performance (IIRC 2013). More specifically, the IIRC recommends that companies produce an integrated report, generally defined as “a concise communication about how an organization’s strategy, governance, performance and prospects, in the context of its external environment, lead to the creation of value over the short, medium and long term” (IIRC 2013, para. 1.1).

As the latest development in a long series of reporting innovations, integrated reporting (IR) has attracted marked attention among academics, practitioners, and policymakers (Baboukardos and Rimmel 2016; Higgins et al. 2014). With respect to international corporate reporting practice, however, the number of companies labeling their reports as integrated has not grown significantly over the last few years (KPMG 2017). In 2017, 14% of N100 and G250 reporting companies produced an integrated report versus 11% of N100 and 15% of G250 reporting companies in 2015 (KPMG 2017).Footnote 1 The overall diffusion of IR is further characterized by considerable geographic variation. For instance, industry observers have noted the pace at which German DAX 30 companies are adopting IR has been slowing down (PwC 2016) and has even been declining in absolute terms among N100 reporting companies from the Netherlands (KPMG 2017). In other parts of the globe, such as Brazil (+16%), Japan (+21%), Mexico (+16%), and Spain (+9%), the number of IR companies experienced significant growth in 2017 (KPMG 2017).

According to the IIRC (2013, p. 2), IR aims to “[e]nhance accountability and stewardship” and is envisaged “as a force for financial stability and sustainability.” The IIRC further sees IR as a means for organizations to provide information that is more attuned to the needs of investors, thereby enabling “a more efficient and productive allocation of capital” (IIRC 2013, p. 2). Despite these (potential) advantages, the IR movement has recently lost some impetus and been the subject of heated debate and controversy (Günther et al. 2017; PwC 2016; Zhou et al. 2017). Within the academic discourse on IR, it is possible to distinguish a division into two camps (Brown and Dillard 2014; Haji and Anifowose 2016). On the one hand, several scholars take a positive view of the IR agenda (e. g., Coulson et al. 2015; Eccles and Armbrester 2011; Phillips et al. 2011). Seen from their perspective, IR is a paradigm shift in corporate reporting practice (Adams 2017), i. e., “a shift from a ‘financial capital market system’ to an ‘inclusive capital market system’” (Coulson et al. 2015, p. 293) with multiple beneficiaries inside and outside the reporting organization (Adams 2017; Eccles and Armbrester 2011). On the other hand, a considerable number of academics have begun to adopt a critical stance toward IR, questioning the new reporting trend on various fronts. Critics have, for instance, scrutinized the capability of IR to bring about profound changes in corporate reporting practice (Stubbs and Higgins 2014) and to promote sustainability (Flower 2015; Thomson 2015). A clear sign of growing skepticism toward IR in academia is also reflected by the recent call “for more research that critiques <IR>’s rhetoric and practice” (Dumay et al. 2016, p. 166).

In recent years, a substantial but heterogeneous body of literature critical of IR has accumulated. As will be discussed in more detail later on, these critical articles address different aspects and problem areas of IR, apply different methodologies, build upon distinct data sources, and focus on various geographic regions. Given the number and diversity of articles critical of IR, we argue that the time is right to review the current state of research on the potential downsides of IR. More specifically, we seek to identify the major lines of criticism that have been put forth against IR in extant research. To reach this objective, we conduct a systematic literature review following the well-established guidelines suggested by Fink (2014). Complementing more broad-ranging reviews of IR (e. g., Dumay et al. 2016; Owen 2013), we contribute to the (critical) IR literature by providing a focused and condensed account of a crucial and evolving stream of research.

Finally, it should be noted that unless the major concerns about IR are tackled, it is not unlikely that practitioners will successively lose interest in the IIRC’s project and that IR will eventually be remembered as a failed reporting initiative (Chaidali and Jones 2017). In carving out the major problem areas of IR, our findings at the same time highlight points where potential intervention could promote the future dissemination of IR. We further identify three priority areas of criticism and discuss the attribution of responsibilities as well as approaches for potential solutions within these areas. Our review therefore adds value and contributes insights to academia and practice alike.

2 Methodology

In light of the increasing quantity of publication outlets, research output, and potentially conflicting findings, literature reviews serve an important function in terms of unearthing “the nuggets of knowledge that lie buried underneath” (Kirca and Yaprac 2010, p. 306). While various review approaches exist, a distinction is commonly made between systematic and traditional (narrative) reviews (Rousseau et al. 2008; Tranfield et al. 2003). In contrast to the latter, systematic reviews approach the literature in a rigorous, transparent, and replicable manner, thereby reducing the risk of biased conclusions (Rousseau et al. 2008; Tranfield et al. 2003).

For the present review, we followed the systematic review guidelines of Fink (2014) by implementing five process steps (as will be outlined in more detail below). We deemed these guidelines suitable as they are well-established and have been widely adopted in previous systematic reviews. For instance, at the time of this writing (August 2018), prior textbook versions of Fink’s (2014) guidelines have received several hundred Google Scholar citations. In addition, these guidelines have been applied in various reviews on closely related topics, including sustainability reporting (Hahn and Kühnen 2013), carbon accounting (Stechemesser and Guenther 2012), and carbon disclosure (Hahn et al. 2015).

As a first step, we specified our research question. Despite offering a plethora of contingent advantages, the IR movement has nevertheless come under increased criticism (as outlined in the following chapter) and has lost some of its momentum (Günther et al. 2017; PwC 2016; Zhou et al. 2017). Our objective was thus to shed light on the potential downsides of IR. More specifically, we aimed to answer the following research question: What major lines of criticism have been put forth against IR in prior research?

Our second step was to identify relevant databases. We selected the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) due to its broad coverage of peer-reviewed journals published in English across various domains (e. g., accounting, finance, management, and business). The SSCI further captures all journals with an impact factor; therefore, it presumably covers the leading academic outlets in the social sciences (Hahn et al. 2015). To obtain even broader coverage of peer-reviewed business journals, we additionally employed the EBSCO Business Source Complete database.

Third, specific search terms were chosen. The search term selection was kept as broad as possible so as not to miss relevant articles, given our intention to cover the research field exhaustively. Building upon our research question, a conscious decision was made to select the search term integrated report*. Employing the asterisk as a truncation symbol allowed us to search for different endings of our search term (e. g., integrated report, integrated reports, integrated reporting).

Fourth, we specified practical screening criteria to include or exclude articles from our literature review. To uphold the standards of scientific quality and rigor, we only considered peer-reviewed journal articles. Furthermore, only English-language literature was incorporated. In October 2017, we applied our search term to titles, abstracts, and keywords in both databases. Our search strategy resulted in a total of 302 articles. Of this sample, 203 articles were obtained from the EBSCO Business Source Complete and 99 articles from the SSCI database. After the deletion of duplicates, a preliminary sample of 243 articles remained. Subsequently, both contributing authors independently screened all the articles in accordance with predetermined steps and criteria. In the first screening round, each article was subject to a quick content check. Articles not focused on the topic of IR were excluded from the review. We further excluded non-English as well as non-academic articles that had found their way into the preliminary literature sample despite the application of the respective limiters in both databases. In the second screening round, we excluded all articles lacking a clear critical perspective toward IR. To determine the (non-)existence of a critical perspective, we searched each article’s title, abstract, and keywords for expressive terms (e. g., critique, criticism, downside, shortcoming, challenge, barrier, obstacle) and words with a negative connotation in the IR context (e. g., ceremonial, symbolic, rhetorical, fashion-setting, impression management).Footnote 2 Finally, we excluded literature reviews from further analysis given our intention to identify the original lines of criticism aimed at IR in extant research. Screening results were compared after each screening round. In rare cases of divergent screening outcomes, the respective articles were screened again and subsequently discussed until a consensus decision was reached. This process resulted in 37 articles of central relevance to the present review.

Fifth, we conducted the actual review of the identified body of literature and synthesized our findings. To accomplish this task, both authors independently engaged with the collected material and summarized each article’s critical perspective toward IR. In this context, we exclusively focused on those points of criticism that were based on the article’s original research and thus of a primary source character—in contrast to criticism that was, for example, simply rephrased in an article’s background or literature review section. While some papers only provided one or very few lines of original criticism, other articles captured a more widespread critique of IR (see Table 3). The individual summaries of both authors were subsequently compared, discussed, and finally consolidated into one primary file. Identified points of critique were then assigned to specific thematic categories, aggregating issues of high similarity into major lines of criticism. Several thematic categories were deductively derived, i. e., developed before the material was analyzed (Seuring and Gold 2012). For this purpose, the IR framework (IIRC 2013) was utilized as a template given its prominent role within the IR movement. Table 1 provides an overview of those analytical categories that were selected from the IR framework (IIRC 2013) and includes a brief summary of each category. Building upon the fundamental concepts and guiding principles of the IR framework (IIRC 2013) allowed us to assign most but not all lines of criticism to specific categories. Therefore, after examining the collected material, one additional thematic category was inductively derived (Seuring and Gold 2012) to account for criticism directly targeted at the IIRC. After the thematic analysis, a descriptive analysis was conducted to provide additional background information about the reviewed articles (see Table 2). Informed by prior literature reviews, the following descriptive categories were applied: research methodology, data collection approach, data source, and geographic focus. The synthesis of our descriptive and thematic findings is presented in the following two chapters.

3 Descriptive analysis

Based on the aforementioned four categories, Table 2 provides an overview of the descriptive analysis findings. With 34 out of 37 articles, the identified body of literature strongly builds upon empirical research methodologies. Among the empirical studies, document analyses (23) and interviews (14) clearly represent the most frequently applied data collection methods. Further empirical methods include quantitative data analyses (3), surveys (2), participant observation (1), and netnography (1). Eleven empirical articles utilize more than one data collection method, predominantly by combining interviews with document analyses. Data sources differ considerably across the reviewed articles. Studies that draw on document analyses primarily investigate the integrated reports of companies or IIRC-related documents, including IIRC discussion papers, comment letters responding to IIRC discussion papers, and responses to the IIRC’s public consultation phases. Interview studies primarily sample participants from the realm of practice, such as sustainability managers, communication managers, report preparers, or audit experts. With respect to the geographic targets of empirical studies, most articles were found to be global in focus (14), followed by studies on South Africa (9) and Australia (4). Further geographic foci capture Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sri Lanka as well as the UK and USA. Only three articles followed a non-empirical research approach, including a commentary, a theoretical paper, and a conceptual paper.

4 Major lines of criticism aimed at IR

In the following, we present the synthesis of our thematic findings. We start with criticism of the fundamental concepts and proceed to major issues surrounding the guiding principles of the IR framework (IIRC 2013). After that, we present the central lines of criticism put forth against the IIRC.

4.1 Criticism of the fundamental concepts

The capitals and the notion of value creation over time, as fundamental concepts of IR, are both heavily criticized in the identified literature. Regarding the concept of value creation, Humphrey et al. (2017), for instance, point out how it is perceived as vague, ambiguous, and one-sided. Zappettini and Unerman (2016) caution against the potential misuse of the term value as a rhetorical tool. Also criticized is the missing acknowledgement that consumption of value represents a necessary prerequisite for the possibility of creating value (Humphrey et al. 2017). Furthermore, Flower (2015, p. 5) poses the key question of: “Value to whom?” Value could, for instance, be interpreted with reference to stakeholders, future generations, or society, but critics find fault with IR for focusing on value to investors (Alexander and Blum 2016; Brown and Dillard 2014; Cheng et al. 2014; Flower 2015; Reuter and Messner 2015; Thomson 2015; Van Bommel 2014). Alexander and Blum (2016, p. 246) criticize how “the key customer of the IIRC is identical” to that of the International Accounting Standards Board and comment how “[t]his does not seem to be a brave new world.” As outlined by Flower (2015, p. 14), the principle of “responsiveness and stakeholder inclusiveness” was at one time included in the IR discussion paper (IIRC 2011) but was later eliminated from the final framework (IIRC 2013). Since then, the primary purpose of IR has been to “explain to providers of financial capital how an organization creates value over time” (IIRC 2013, p. 4). Van Bommel (2014, pp. 1177–1178) concludes that IR has become a compromise of which the focus “is no longer the common good of many, but is rather the specific interest of a few […]”.

The discussion surrounding the notion of value creation is not limited to the intended user of an integrated report but also captures the type of organization that produces an integrated report. Simnett and Huggins (2015, p. 36) draw attention to the fact that pursuant to the IR framework (IIRC 2013, para. 1.4), IR is also intended for organizations with “a broader mandate than generating financial profit, such as government and NFPs.” In light of the investor focus, however, the relevance of IR for these users is yet to be determined (Simnett and Huggins 2015).

Due to the interwoven nature of fundamental concepts, the investor focus comes along with direct consequences for the disclosure of information on the six capitals. In this context, the identified literature is characterized by widespread uncertainty surrounding the terminology of capitals, as prevalent definitions leave ample room for interpretation (Cheng et al. 2014; Coulson et al. 2015; Flower 2015; Humphrey et al. 2017; Perego et al. 2016). Furthermore, reporting on capitals is only required if the creation of value is affected—value, as discussed above, being de facto defined as value to investors. Under this premise, specifics on some forms of capitals, especially natural capital, may often not require inclusion in an integrated report (Flower 2015). Based on the interpretation of value as value to investors and due to the lack of clear definitions of the capitals, several authors express great concern that integrated reports primarily focus on financial capital (Alexander and Blum 2016; Cheng et al. 2014; Flower 2015; Humphrey et al. 2017; Simnett and Huggins 2015; Zappettini and Unerman 2016).

Another line of argument that is central to the criticism of the capitals relates to the reporting of trade-offs among multiple capitals (IIRC 2013, para. 4.56). The topic of trade-offs is largely seen as being problematic in the literature, particularly in light of their susceptibility to abuse (Cheng et al. 2014; Flower 2015; Haji and Anifowose 2016, 2017; Robertson and Samy 2015; Simnett and Huggins 2015). Trade-offs between natural and financial capitals may, for instance, pose an intriguing opportunity for organizations to easily justify negative environmental impacts and to engage in self-promotion (Cheng et al. 2014; Flower 2015). Furthermore, reporting trade-offs is only feasible if capitals can be consistently and comparably measured, a premise that is often rejected in the literature (Cheng et al. 2014; Coulson et al. 2015; Flower 2015; Humphrey et al. 2017; Searcy and Buslovich 2014; Simnett and Huggins 2015). Along with these “complexities of measurement”, Robertson and Samy (2015, p. 207) note the lack of guidance by the IIRC as a decisive cause for companies failing to adopt the core concept of capital measurement, resulting in a subjective measurement of capitals. Subjectivity in measurement also leaves room for obscuring or dismissing negative trade-offs, as observed in corporate reporting practice (Haji and Anifowose 2016, 2017; Haji and Hossain 2016). Robertson and Samy (2015, p. 195) conclude that the difficulties surrounding the concept of multiple capitals “can be an obstacle to the innovation of new trends in the adoption of IR”. Flower (2015, p. 8), however, sees the concept of multiple capitals itself merely as “a means of enabling firms to justify damaging the environment.”

In light of the above, it becomes apparent why many authors argue that IR is far from fostering or contributing to sustainability (Alexander and Blum 2016; Brown and Dillard 2014; Flower 2015; van Bommel 2014; Zappettini and Unerman 2016). Brown and Dillard (2014, p. 1147), for example, conclude that IR “may code well with mainstream accounting and existing governance structures that privilege finance capital” but “is likely to take us ever further away from social and environmental reporting that might promote corporate accountability, stakeholder empowerment, democratic governance and sustainability.” Van Bommel (2014) acknowledges that IR originally tried to combine different logics of valuation but stresses the risk of IR becoming a private arrangement in which investor concerns are privileged over societal and environmental ones. Flower (2015, p. 8) succinctly speaks of the “abandoning of sustainability”, whereas Alexander and Blum (2016) conclude that a reporting framework addressing the problems of current sustainability reporting still needs to be invented.

4.2 Criticism of the guiding principles

The IR framework (IIRC 2013) is built on seven guiding principles that guide the preparation and presentation of an integrated report. These principles are (1) strategic focus and future orientation, (2) connectivity of information, (3) stakeholder relationships, (4) materiality, (5) conciseness, (6) reliability and completeness, and (7) consistency and comparability (IIRC 2013). In the following, we present the central lines of criticism surrounding these guiding principles. As these principles are also reflected in the fundamental concepts, the following presentation is complemented by several issues already outlined in the previous section.

The guiding principle of (1) strategic focus and future orientation deals with risks and opportunities that may affect value creation over time as well as descriptions of the organization’s business model and its relation to strategic objectives. The IR framework further calls for a connection of the organization’s past and future performance and a description of how future strategic decisions will build on lessons learned in the past (IIRC 2013, paras. 3.3–3.5). The principle of (1) strategic focus and future orientation has caused some confusion among scholars and practitioners alike (Reuter and Messner 2015; Stacchezzini et al. 2016; Steyn 2014). As with many terms in the IR framework (IIRC 2013), the definition of the term future is not well specified, implying that the exact time frame remains unclear (Reuter and Messner 2015). Furthermore, the critical issue has been raised of how organizations can provide useful content on future outlook and strategy without giving away sensitive information (James 2015; Reuter and Messner 2015; Stacchezzini et al. 2016; Steyn 2014; Strong 2015; Veltri and Silvestri 2015). It therefore comes as no surprise that integrated reports have been found to provide little information on future orientation in practice (Melloni 2015; Melloni et al. 2016; Stacchezzini et al. 2016). A lack of or biased disclosure of information on future orientation may also be interpreted as one indicator of organizational impression management (Haji and Anifowose 2016; Melloni 2015; Melloni et al. 2016; Stacchezzini et al. 2016).

The second guiding principle, (2) connectivity of information, is closely linked with the process of integrated thinking. According to this principle, organizations are asked to provide a holistic picture of those factors creating value over time, thereby ensuring dynamic and interconnected communication. The interdependencies of the capitals, the links between financial information and other information, between past and future information, as well as between types and sources of information should be reported (IIRC 2013, paras. 3.6–3.9). Here again, difficulties regarding the exact meaning of key terminology have been criticized; in particular, integrated thinking has been described as “unclear and challenging” (Feng et al. 2017, p. 339). These difficulties are also reflected in reporting practice as organizations often do not take the principle of connectivity fully into consideration when producing integrated reports (Burke and Clark 2016; Gunarathne and Senaratne 2017; Haji and Anifowose 2016, 2017; Haji and Hossain 2016; Robertson and Samy 2015; Veltri and Silvestri 2015). Internal struggles and even resistance constitute significant obstacles to the full adoption of integrated thinking as employees find it hard to cope with fundamental changes and the new way of thinking within the organization (Burke and Clark 2016; Stubbs and Higgins 2014). Practitioners have even described integrated thinking as “a painful process by which organizations are pushed to report on things that might make them uncomfortable” (Burke and Clark 2016, p. 277). Thus, IR practice often only serves to bring about first-order change but no second-order change (Feng et al. 2017; Gunarathne and Senaratne 2017; Stubbs and Higgins 2014). The former entails the intensification of existing structures of sustainability reporting; the latter, however, requires that a transformative change throughout the entire organization take place (Stubbs and Higgins 2014). For instance, some organizations still have not implemented a single database dedicated to capturing all relevant information but rather maintain their former, separate ones. Moreover, departments of finance and sustainability often remain separated by location, thus hindering cross-functional communication (Robertson and Samy 2015). In addition, no shift of ownership (i. e., change in who is involved in the reporting process) has occurred, and there appears to be a lack of engagement of finance departments (Stubbs and Higgins 2014). Overall, organizations appear to be continuing to work in functional silos by separating internal decision-making processes from external reporting (Perego et al. 2016; Robertson and Samy 2015). This lack of connectivity of information is often interpreted as one indication of impression management and legitimation strategy; although several studies have found the amount of information disclosure to be increasing, no respective increase in connectivity has been documented (Haji and Anifowose 2016, 2017; Setia et al. 2015). Gunarathne and Senaratne (2017) add that even when the principle of connectivity seems to be followed, it may merely be the imitation of a successful IR adopter to serve a legitimation strategy and ensure competitive advantage.

The third guiding principle, (3) stakeholder relationships, requires organizations to report insights about their relations with key stakeholders and how they respond to stakeholders’ needs (IIRC 2013, paras. 3.10–3.16). In this context, organizations have expressed concerns about the feasibility of producing a report that is understandable to the stakeholders (Rensburg and Botha 2014; Veltri and Silvestri 2015). In addition, practical difficulties in mapping all stakeholders have been raised (Vorster and Marais 2014). After the release of the 2011 discussion paper (IIRC 2011), concerns about possible tensions between an investor focus and responsiveness and stakeholder inclusiveness emerged (Reuter and Messner 2015). As discussed above, emphasis was placed on financial capital providers in the IIRC framework of 2013; nevertheless, organizations may not concur with this approach and adopt a broader definition of stakeholder (Beck et al. 2017). Beck et al. (2017) point out that, consequentially, organizations may determine that a static annual integrated report is not sufficient to meet the needs of the information recipients. They assert that it is unlikely that a static annual integrated report would meet the financial capital providers’ information needs “as such users continuously seek information from all available sources” (Beck et al. 2017, p. 203).

Another issue raised in relation to the principle of (3) stakeholder relationships is the question of stakeholder involvement as an “ordinary part of conducting business” in organizations in which integrated thinking is successfully embedded (IIRC 2013, para. 3.13). Searcy and Buslovich (2014) find that companies often do not, or only poorly, involve external stakeholders in decision-making and business management or consider their input. Haji and Anifowose (2016, p. 207) speak of “symbolic gestures of stakeholder relationships” and describe disclosures on stakeholder relationships as “soft and generic” and part of legitimation strategy.

(4) Materiality forms the fourth guiding principle of the IR framework (IIRC 2013, paras. 3.17–3.35). This principle refers to matters substantively affecting an “organization’s ability to create value over the short, medium and long term” (IIRC 2013, para. 3.17). Relevant matters need to be identified, evaluated in terms of their performance, and subsequently prioritized (IIRC 2013, para. 3.18). Closely linked to the guiding principle of (4) materiality are the principle of (5) conciseness as well as the notion of completeness, a component of the guiding principle of (6) reliability and completeness (IIRC 2013, paras. 3.36–3.38, 3.39 and 3.47–3.53). The former calls for an integrated report of sufficient length “without being burdened” with irrelevant information (IIRC 2013, para. 3.37), whereas the latter requires organizations to disclose all positive and negative information that is material. As Reuter and Messner (2015) observe, the investor focus—as clarified in the IR framework (IIRC 2013)—may answer the question “material to whom?” However, this does not sort out all issues surrounding the principle of (4) materiality, and significant uncertainties remain. Chaidali and Jones (2017, p. 14), for instance, explicitly identify the lack of guidance provided by the IIRC on “what needs to be disclosed” as responsible for the hesitation of organizations to adopt IR.

Among those who do adopt IR, research shows that organizations face difficulties with identifying truly relevant matters; in particular, the balanced disclosure of positive and negative matters is often not well applied in practice (Haji and Anifowose 2016, 2017; Maniora 2017; Melloni 2015; Searcy and Buslovich 2014; Stubbs and Higgins 2014). Stubbs and Higgins (2014) point out the subjectivity of the principle of (4) materiality and the danger that organizations may exclude reporting information that is subjectively not considered material. This process has been described as “picking and choosing” (cited in Stubbs and Higgins 2014, p. 1085). In particular, the lack of guidance may be misused by organizations in service of their legitimation strategy and impression management (Beck et al. 2017; Gunarathne and Senaratne 2017; Haji and Anifowose 2016, 2017; Haji and Hossain, 2016; Melloni 2015; Melloni et al. 2016; Zappettini and Unerman 2016). Reported information tends to remain rather vague, rudimentary, and not company-specific; furthermore, the disclosure of negative material issues is often lacking (Gunarathne and Senaratne 2017; Haji and Anifowose 2016, 2017; Haji and Hossain 2016). Haji and Anifowose (2016) observe selectivity in the information disclosed in the form of a strong focus on positive information. They further find “uniformity in the positive tone of disclosure language”, thereby following a reporting pattern that focuses on soft social spots, such as disadvantaged groups (Haji and Anifowose 2016, p. 210). This finding is further amplified by Melloni et al. (2016), who report that a positive tone in the reports is associated with disclosure manipulation. Similarly, Melloni (2015) refers to thematic manipulation regarding the disclosure of intellectual capital, as a positive tone of information disclosure on intellectual capital is found to be associated with declining performance. Zappettini and Unerman (2016, p. 538) conclude that “IRs “sustainability talk” was appropriated as a legitimacy tool” in order to portray “the organization as a trustworthy agent.”

Delving more deeply into the principle of (5) conciseness, several authors found that reports were excessive in length, lacking in focus, and less readable (Chaidali and Jones 2017; Haji and Anifowose 2016, 2017; Haji and Hossain 2016; Maniora 2017; Melloni et al. 2017; Rensburg and Botha 2014). Although IR was intended to reduce the amount of reported information and to render that information more concise and readable, it appears that the quantity of information is nevertheless increasing (Rensburg and Botha 2014; Setia et al. 2015). Organizations might be overwhelmed by the task of disclosing material information while keeping this information concise and without fragmentation at the same time (Reuter and Messner 2015; Searcy and Buslovich 2014). An alternative explanation could be, yet again, that organizations capitalize on the lack of guidance by employing a legitimation strategy, i. e., providing a large amount of positive information (Melloni et al. 2017).

Selectivity, fragmentation, and lack of balance, as discussed above under the principles of (4) materiality and (5) conciseness, often lead to incomplete integrated reports that violate the notion of completeness under the principle of (6) reliability and completeness (Gunarathne and Senaratne 2017; Haji and Anifowose 2016; Melloni et al. 2017). However, this lack of completeness may also be due to difficulties in obtaining relevant high-quality data (Burke and Clark 2016; Searcy and Buslovich 2014). The process of data collection may seem “never-ending and time-consuming”; data must be collected and validated, usability must be determined, and appropriate data storage and analysis systems are required (Burke and Clark 2016, p. 277). Staff availability poses another issue in that regard (Searcy and Buslovich 2014). Thus, the issue of completeness significantly builds upon the cost dimension, which has been found to be a substantial burden for organizations generating an integrated report (Chaidali and Jones 2017; James 2015; Searcy and Buslovich 2014; Steyn 2014).

The issue of cost directly leads to the notion of reliability, a component of the guiding principle of (6) reliability and completeness, which requires that integrated reports be free of any material error. The IR framework (IIRC 2013, para. 3.40) suggests using mechanisms to enhance the reliability of reports, “such as robust internal control and reporting systems, stakeholder engagement, internal audit or similar functions, and independent, external assurance.” In this context, the assurance of integrated reports is a major topic in the academic debate (Burke and Clark 2016; Cheng et al. 2014; Humphrey et al. 2017; Maroun 2017; Simnett and Huggins 2015; Veltri and Silvestri 2015). Simnett and Huggins (2015) question whether traditional assurance mechanisms are applicable to integrated reports. They further mention the costs and challenges associated with the determination of assurance levels and standards, specifically with regard to future-oriented information. Maroun (2017) criticizes how little guidance is given on this assurance engagement, especially with respect to the technical approach (i. e., criteria for assurance) and scope. Maroun (2017) further points out how challenging assurance becomes, considering that multiple types of data (e. g., factual, soft, qualitative, quantitative) are used and reported. Burke and Clark (2016) also see the variation in sources for assurance as a major issue as well as the lack of unified standards for assurance. Veltri and Silvestri (2015) express concern that there might be a trade-off between the assurance of reliable information and providing accountable information. Assurance encourages a rather formal adoption, “to the detriment of a real process of accountability towards organizational stakeholders” (Veltri and Silvestri 2015, p. 456). Cheng et al. (2014) additionally mention liability concerns for accounting firms, whereas Humphrey et al. (2017) claim that an IR profession, which would provide the necessary specialists, is still lacking. Others, in contrast, argue “the Integrated Report might be a means for external organisations (e. g., accounting firms, lawyers, and design consultants) to market additional services to help organisations prepare their Integrated Reports” (Chaidali and Jones 2017, p. 11).

The principle of (6) reliability and completeness also addresses the responsibility of an organization’s management. According to the IR framework (IIRC 2013, para. 3.41; see also para. 1.20), “[t]hose charged with governance […] are responsible for ensuring that there is effective leadership and decision-making regarding the preparation and presentation of an integrated report, including the identification and oversight of the employees actively involved in the process.” In line with this, the identified literature highlights the role of management as change agent, i. e., the driver of organizational change toward integrated thinking (Perego et al. 2016; Robertson and Samy 2015). If the adoption of integrated thinking is to be successful, the internal promotion of IR needs to be realized throughout all levels of the organization (Feng et al. 2017; Stubbs and Higgins 2014). In this context, the management should be “visually leading and supporting” (as cited in Feng et al. 2017, p. 340). Stated differently, “a buy-in from top-level management” is necessary to “sell the process internally” (Burke and Clark 2016, p. 277). However, the lack of such support is found to be a major constraint in establishing an integrated report (Chaidali and Jones 2017; Gunarathne and Senaratne 2017).

Last but not least, IR is guided by the principle of (7) consistency and comparability. The former refers to consistent reporting from one period to another, whereas the latter calls for the comparability of reports among organizations. Although the latter principle carries with it the notion of standardization across organizations, this possibility is often questioned in the literature (Beck et al. 2017; Lueg et al. 2016; Reuter and Messner 2015; Stubbs and Higgins 2014). According to the empirical findings of Haji and Anifowose (2016, p. 213), integrated reports are “inconsistent over time and across organizations” and thus not conducive to increasing standardization. Although standardization has been found to be important to encourage significant internal change (Stubbs and Higgins 2014), there is considerable resistance to the idea that such standardization works across different types of organizations and sectors. Reuter and Messner (2015), for example, anticipate a trade-off between the comparability and truthfulness of reports and further question the feasibility of applying the same performance metrics even to organizations in the same sector. Lueg et al. (2016, p. 30) do not see IR as a “one size fits all solution” either, but instead recommend company-specific approaches, particularly in the case that more regulators decide to make IR mandatory. Beck et al. (2017, p. 203) point out that as part of legitimation strategy, organizations might use IR “as they see fit.” Stubbs and Higgins (2014) state that there will be no comparability until IR has matured, whereas Beck et al. (2017, p. 203) conclude that “the IIRC’s vision of IR as a standardised means […] might never be realised in practice.”

4.3 Criticism of the IIRC

In the identified body of literature, criticism is not limited to the IR framework’s fundamental concepts and guiding principles (IIRC 2013) but also extends to the IIRC as a governing body. Critical questions reflecting the essence of this debate include: Who is involved in the development and shaping of IR? Who is excluded from that process? How do the interests of those involved shape the (original) idea of IR?

Pursuant to the IIRC constitution, the body of council members comprises various stakeholders ranging from providers of financial capital to regulators, accountants, and representatives of civil society (IIRC 2015a, para. 1.2). Flower (2015) sees the decisive reason for the failure of the original idea in the structure of the IIRC, which allows the undermining of the idealists by the realists. The idealists include all council members who support environmental and social accounting, whereas the realists encompass accountants, preparers, and regulators (Flower 2015). Alexander and Blum (2016, p. 246) agree and describe how “regulatory capture was achieved before the process had even publicly started.” During the drafting processes of the IR framework, the realist group held the majority within the IIRC. Flower (2015) therefore concludes that the notion of sustainability was stepwise abandoned and the interests of accountants and preparers took over.

Chaidali and Jones (2017, p. 2) look at the development of IR from the angle of trustworthiness, criticizing the IIRC as being “an abstract, impersonal coalition of the professional accounting elite” pursuing nothing beyond their own interests. Following this line of thought, IR acts as a self-serving mechanism seeking to convince organizations that they are in need of specialized experts’ knowledge to enable them to produce an integrated report. The IIRC is therefore seen as being commercially driven, thereby undermining the trust of other stakeholder groups as well as the future success of IR. Humphrey et al. (2017) argue that IR appealed to the dominant stakeholder group (i. e., the realists) not because they saw it as a reform of the widely criticized former method of corporate reporting but rather merely as an opportunity to shape IR in the way that was most beneficial to them. Strong (2015) notes that important stakeholder groups (such as civic interest groups) were either excluded from the process of establishing IR or consequently withdrew when their concerns were no longer heard. After the realists had taken over the drafting process, the principle of “responsiveness and stakeholder inclusiveness” was eliminated from the final framework, with a consequent emphasis on the investor focus of IR (Flower 2015, p. 14).

Humphrey et al. (2017) add how at first the IIRC had “strong advantages of timing, of being in the “right” place at the “right” time” to answer the overall call for transparency and accountability after the global financial crisis; however, such “winds of time” can change easily and “blow with great contrary force” (Humphrey et al. 2017, pp. 56–57). According to Humphrey et al. (2017, p. 57), “it remains to be seen whether any conceptual, financial or social and environmental storm will hinder the development” of IR. Flower (2015) and Thomson (2015), however, see failure as already well underway. Thomson (2015) asserts that the formerly idealistically driven IIRC has been overshadowed by capitalist views, with IR ending up being the wrong tool for pursuing the goal of sustainability. Flower (2015, p. 17) makes clear that the IIRC is a “severe disappointment for those […] who had hoped for a fundamental reform of financial reporting.”

5 Discussion and conclusion

According to the IIRC (2013) and many advocates from the realm of practice, IR “should be the next step in the evolution of corporate reporting” (IIRC 2013, p. 1) and eventually become the “new corporate reporting norm” per se (IIRC 2013, p. 2). However, a blind and uncritical acceptance of IR as the new reporting norm entails the risk that organizations will lavish resources on a reporting approach that might fall short of its promise (Dumay et al. 2016). Academic research therefore plays an important role in terms of directing (practitioners’) attention to the potential problems, limitations, and downsides of IR. Although a division of camps can be distinguished in the academic discourse on IR (Brown and Dillard 2014; Haji and Anifowose 2016), critical voices have increasingly been raised.

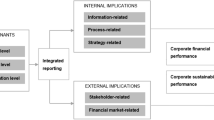

Based on a synthesis of 37 critical articles, our review shows that the central lines of academic criticism can be assigned to each of the fundamental concepts and guiding principles of the IR framework (IIRC 2013) as well as to the IIRC as the governing body. As such, we have identified and highlighted decisive problem areas that need to be addressed before IR can be expected to stand the test of time. From a practical perspective, these problem areas may be viewed as potential intervention points for promoting the future dissemination and acceptance of IR.Footnote 3 Table 3 depicts all the original lines of criticism identified across the reviewed articles. An examination of the distribution of criticism indicates that three categories are most prevalent in extant research, namely, reliability and completeness (17); the capitals (15); and materiality (13). From an academic perspective, these three categories can thus be seen as urgent priority aspects that deserve particular attention in practice. However, questions arise regarding who is responsible for these criticisms, which actor(s) should become active, and how the respective issues might be resolved in the future.

With respect to criticism linked to the guiding principle of reliability and completeness, our review findings indicate that most scholars view external assurance as a promising if not vital step. Yet, the debate on assurance on IR is still evolving and various obstacles need to be overcome, including a broad range of technical and methodological issues (IIRC 2015b). Furthermore, it needs to be emphasized that “[t]he IIRC does not see itself as a standard setter for assurance on <IR>, but it recognizes the role of assurance in enhancing credibility and trust […]” (IIRC 2018). As such, various actors are called to promote the practice of external assurance on IR. However, as long as an IR profession is still lacking (Humphrey et al. 2017), increasing regulatory involvement and pressure can be seen as promising drivers of professional development. Although the guiding principle of reliability and completeness is unlikely to be satisfactorily put into practice without external assurance, the role and importance of complementary internal assurance mechanisms are not to be neglected. As organizations possess the means to promote the reliability of their corporate data through internal audits and controls over information flows, responsibility for criticism and problem-solving capacity both fall under the purview of reporting companies as well.

The capitals, one of the fundamental concepts of IR, have attracted considerable criticism in the academic literature. In this context, the central lines of critique relate to terminological uncertainty, the focus on financial capital, and the issue of trade-offs among multiple capitals. Considering the problem of terminological fuzziness, responsibility can be assigned to the IIRC as the composer of the IR framework (IIRC 2013). One potential avenue for mediating this issue in the future could lie in a supplementary IIRC publication specifically devoted to the clarification of the capitals concept. The development of such a document could, for instance, be grounded on the consultation of different stakeholders, a comment period, and a collection of best-practice examples. Regarding the focus on financial capital and the issue of trade-offs, we associate the underlying root causes and responsibilities to “an overly influential power block” during the IR discussion paper phases (Reuter and Messner 2015, p. 392). A possible solution could be the reopening of a dialog among the IIRC, IR practitioners and preparers, and those interest groups that withdrew from the debate when their concerns were no longer heard. Yet, given the dominance and interests of the financial capital providers, this is clearly not a likely scenario, although possible approaches have been put forth in prior research (e. g., Alexander and Blum 2016; van Bommel 2014).

As regards the guiding principle of materiality, our review has shown that organizations tend to experience considerable difficulties with identifying material information due to a lack of guidance in the IR framework (IIRC 2013). In light of this, responsibility for materiality-related criticism can again be assigned to the IIRC, the governing body and composer of the IR framework (IIRC 2013). However, our review also captures research findings indicating that the corporate disclosure of negative material information is often lacking. As such, responsibility can also be attributed to those IR organizations that misuse the lack of guidance as part of legitimation strategy. With respect to potential solutions, we believe that a crucial first step was already taken by the IIRC and the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) at the end of 2015, namely, the publication of a technical guidance paper specifically devoted to materiality in IR (IIRC and IFAC 2015). We strongly recommend this complementary source to all practitioners interested in the issue of materiality and particularly to those organizations struggling with the separation of material from non-material information. Naturally, the technical guidance paper provides no substantial problem-solving capacity when considering those IR companies that intentionally exploit their degree of freedom to serve legitimation strategy. In this context, one may argue that financial capital providers will play an important role in terms of exerting discipline over IR companies. This point of view is supported by the recent empirical finding that “the improvement in the level of alignment of integrated reports with the <IR> framework is associated with a subsequent reduction in the cost of equity capital and the realized market returns” (Zhou et al. 2017, p. 123). Stated differently, “investors are willing to accept a lower rate of return as a result of reduced information risk” (Zhou et al. 2017, p. 123), implying a strong financial incentive to generate an integrated report in accordance with the IR framework (IIRC 2013).

Our findings should be considered in light of several potential limitations related to the systematic review approach, namely, objectivity, validity, reliability, and generalizability (Hahn and Kühnen 2013). To ensure objectivity, we followed the systematic review process as outlined in the second chapter. A limitation might be seen in our choice of databases and the exclusive focus on English-language literature. However, both databases represent major knowledge sources for social science research, and English is the primary language of the international research community (Narvaez-Berthelemot and Russell 2001). In addition, an unrestricted approach to material collection and analysis is unfeasible, implying that researchers inevitably need to “choose the reasonable from the feasible” and balance “input and yield” (Seuring and Gold 2012, p. 552). This study aimed for validity by adhering to the review guidelines suggested by Fink (2014). Given their widespread application in prior research, we deemed those guidelines applicable and valid for the review at hand. Our focus on peer-reviewed journal articles further enhanced validity, given that the peer-review process is generally regarded as an effective measure to promote validity (Hahn and Kühnen, 2013; Spina et al. 2013). To enhance reliability, both contributing authors independently screened and analyzed the collected material before jointly synthesizing the review’s findings. This study aimed for generalizability by employing two major databases and selecting a broad search term. However, importantly, no claim of generalizability beyond the reviewed material is made.

Notes

According to the KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2017 (KPMG 2017), about one-third of companies label their reports as integrated without specific reference to the IIRC framework. However, and for the sake of clarity, this article uses the terms integrated reporting and integrated report(s) in the following chapters exclusively to refer to those reports that comply with the IIRC reporting framework. The abbreviation G250 captures “the world’s 250 largest companies by revenue based on the Fortune 500 ranking of 2016,” whereas N100 “refers to a worldwide sample of 4900 companies comprising the top 100 companies by revenue in each of the 49 countries researched” in the study (KPMG 2017, p. 3).

The term impression management is generally defined as “the process by which individuals attempt to control the impressions others form of them” (Leary and Kowalski 1990, p. 34). In the specific context of corporate reporting practice, impression management refers to “the tendency for the organization to use data selectively and present them in a favourable light to manipulate audience perceptions of corporate achievements” (Melloni 2015, p. 665).

We fully acknowledge that the identified points of criticism are not necessarily unique to IR. For instance, the principle of reliability has also been subject to criticism and controversial debate within the context of sustainability (Boiral and Henri 2017) and financial reporting (Zhang 2012). In contrast to these reporting approaches, however, IR is far from being a mainstream reporting practice. We therefore argue that all identified points of criticism deserve attention within the IR movement, although some issues are applicable to reporting frameworks in general.

All 37 articles included in our review are marked with an asterisk (*).

References

All 37 articles included in our review are marked with an asterisk (*).

Adams C (2017) Understanding integrated reporting: The concise guide to integrated thinking and the future of corporate reporting. Routledge, New York

* Alexander D, Blum V (2016) Ecological economics: A Luhmannian analysis of integrated reporting. Ecol Econ 129:241–251

Atkins J, Atkins BC, Thomson I, Maroun W (2015) “Good” news from nowhere: Imagining utopian sustainable accounting. Account Auditing Account J 28:651–670

Baboukardos D, Rimmel G (2016) Value relevance of accounting information under an integrated reporting approach: A research note. J Account Public Policy 35(4):437–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2016.04.004

* Beck C, Dumay J, Frost G (2017) In pursuit of a ‘single source of truth’: From threatened legitimacy to integrated reporting. J Bus Ethics 141:191–205

Boiral O, Henri JF (2017) Is sustainability performance comparable? A study of GRI reports of mining organizations. Bus Soc 56:283–317

* Bommel K van (2014) Towards a legitimate compromise? An exploration of integrated reporting in the Netherlands. Account Auditing Account J 27:1157–1189

* Brown J, Dillard J (2014) Integrated reporting: On the need for broadening out and opening up. Account Auditing Account J 27:1120–1156

* Burke JJ, Clark CE (2016) The business case for integrated reporting: Insights from leading practitioners, regulators, and academics. Bus Horiz 59:273–228

* Chaidali P, Jones MJ (2017) It’s a matter of trust: Exploring the perceptions of integrated reporting preparers. Crit Perspect Account 48:1–20

* Cheng M, Green W, Conradie P, Konishi N, Romi A (2014) The international integrated reporting framework: Key issues and future research opportunities. J Int Financ Manag Account 25(1):90–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/jifm.12015

Cohen JR, Holder-Webb LL, Nath L, Wood D (2012) Corporate reporting on nonfinancial leading indicators of economic performance and sustainability. Account Horiz 26(1):65–90. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-50073

* Coulson AB, Adams CA, Nugent MN, Haynes K (2015) Exploring metaphors of capitals and the framing of multiple capitals. Sustain Account Manag Policy J 6:290–314

Dumay J, Bernardi C, Guthrie J, Demartini P (2016) Integrated reporting: A structured literature review. Account Forum 40:166–185

Eccles R, Armbrester K (2011) Integrated reporting in the cloud. IESE Insight 8:13–20

Fasan M, Mio C (2017) Fostering stakeholder engagement: The role of materiality disclosure in integrated reporting. Bus Strategy Environ 26:288–305

* Feng T, Cummings L, Tweedie D (2017) Exploring integrated thinking in integrated reporting—an exploratory study in Australia. J Intellect Cap 18:330–353

Fink A (2014) Conducting research literature reviews. From the Internet to paper, 4th edn. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

* Flower J (2015) The international integrated reporting council: A story of failure. Crit Perspect Account 27:1–17

* Gunarathne N, Senaratne S (2017) Diffusion of integrated reporting in an emerging South Asian (SAARC) nation. Manag Auditing J 32:524–548

Günther E, Herrmann J, Lange A (2017) Hemmnisse der integrierten Berichterstattung: Warum entscheiden sich Unternehmen gegen die Umsetzung? Z Corp Gov 17:97–144

Hahn R, Kühnen M (2013) Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J Clean Prod 59:5–21

Hahn R, Reimsbach D, Schiemann F (2015) Organizations, climate change, and transparency: Reviewing the literature on carbon disclosure. Organ Environ 28:80–102

* Haji AA, Anifowose M (2016) The trend of integrated reporting practice in South Africa: Ceremonial or substantive? Sustain Account Manag Policy J 7:190–224

* Haji AA, Anifowose M (2017) Initial trends in corporate disclosures following the introduction of integrated reporting practice in South Africa. J Intellect Cap 18:373–399

* Haji AA, Hossain DM (2016) Exploring the implications of integrated reporting on organisational reporting practice. Qual Res Account Manage 13(4):415–444. https://doi.org/10.1108/qram-07-2015-0065

Higgins C, Stubbs W, Love T (2014) Walking the talk(s): Organisational narratives of integrated reporting. Account Auditing Account J 27:1090–1119

* Humphrey C, O’Dwyer B, Unerman J (2017) Re-theorizing the configuration of organizational fields: The IIRC and the pursuit of ‘enlightened’ corporate reporting. Account Bus Res 47:30–63

IIRC (2011) Towards integrated reporting: Communicating value in the 21st century. http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/IR-Discussion-Paper-2011_spreads.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2017

IIRC (2013) The international 〈IR〉 framework. http://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/13-12-08-THE-INTERNATIONAL-IR-FRAMEWORK-2-1.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2017

IIRC (2015a) Constitution of the international integrated reporting council. http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/IIRC-CONSTITUTION-2015-SEPTEMBER.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2018

IIRC (2015b) Assurance on 〈IR〉: Overview of feedback and call to action. http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/IIRC-Assurance-Overview-July-2015.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2018

IIRC (2018) Assurance on 〈IR〉http://integratedreporting.org/resource/assurance/. Accessed 15 May 2018

IIRC, IFAC (2015) Materiality in 〈IR〉: Guidance for the preparation of integrated reports. http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/1315_MaterialityinIR_Doc_4a_Interactive.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2018

* James ML (2015) Accounting majors’ perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of sustainability and integrated reporting. J Legal Ethical Regul Issues 18:107–123

Kirca AH, Yaprac A (2010) The use of meta-analysis in international business research: Its current status and suggestions for better practice. Int Bus Rev 19:306–314

KPMG (2017) The road ahead. The KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2017. http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/kpmg-survey-of-corporate-responsibility-reporting-2017.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2018

Leary MR, Kowalski RM (1990) Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychol Bull 107:34–47

* Lueg K, Lueg R, Andersen K, Dancianu V (2016) Integrated reporting with CSR practices: A pragmatic constructivist case study in a Danish cultural setting. Corp Commun Int J 21:20–35

* Maniora J (2017) Is integrated reporting really the superior mechanism for the integration of ethics into the core business model? An empirical analysis. J Bus Ethics 140:755–786

* Maroun W (2017) Assuring the integrated report: Insights and recommendations from auditors and preparers. Br Account Rev 49:329–346

* Melloni G (2015) Intellectual capital disclosure in integrated reporting: An impression management analysis. J Intellect Cap 16:661–680

* Melloni G, Stacchezzini R, Lai A (2016) The tone of business model disclosure: An impression management analysis of the integrated reports. J Manage Gov 20(2):295–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-015-9319-z

* Melloni G, Caglio A, Perego P (2017) Saying more with less? Disclosure conciseness, completeness and balance in integrated reports. J Account Public Policy 36(3):220–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2017.03.001

Narvaez-Berthelemot N, Russell J (2001) World distribution of social science journals: A view from the periphery. Scientometrics 51:223–239

Owen G (2013) Integrated reporting: A review of developments and their implications for the accounting curriculum. Account Educ 22:340–356

* Perego P, Kennedy S, Whiteman G (2016) A lot of icing but little cake? Taking integrated reporting forward. J Clean Prod 136:53–64

Phillips D, Watson L, Willis M (2011) Benefits of comprehensive integrated reporting. Financ Exec 27:26–30

PwC (2016) Integrated reporting in Germany. The DAX 30 benchmark survey 2015. https://www.pwc.de/de/rechnungslegung/assets/studie-integrated-reporting-2015.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2017

* Rensburg R, Botha E (2014) Is integrated reporting the silver bullet of financial communication? A stakeholder perspective from South Africa. Public Relat Rev 40:144–152

* Reuter M, Messner M (2015) Lobbying on the integrated reporting framework: An analysis of comment letters to the 2011 discussion paper of the IIRC. Account Auditing Account J 28:365–402

* Robertson FA, Samy M (2015) Factors affecting the diffusion of integrated reporting—a UK FTSE 100 perspective. Sustain Account Manag Policy J 6(2):190–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/sampj-07-2014-0044

Rousseau DM, Manning J, Denyer D (2008) Evidence in management and organizational science: Assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through reflective reviews. Acad Manag Ann 2:475–515

* Searcy C, Buslovich R (2014) Corporate perspectives on the development and use of sustainability reports. J Bus Ethics 121:149–169

* Setia N, Abhayawansa S, Joshi M, Huynh AV (2015) Integrated reporting in South Africa: Some initial evidence. Sustain Account Manag Policy J 6:397–424

Seuring S, Gold S (2012) Conducting content-analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management. J Supply Chain Manag 17:544–555

* Simnett R, Huggins AL (2015) Integrated reporting and assurance: Where can research add value? Sustain Account Manag Policy J 6:29–53

Spina G, Caniato F, Luzzini D, Ronchi S (2013) Past, present and future trends of purchasing and supply management: An extensive literature review. Ind Mark Manag 42:1202–1212

* Stacchezzini R, Melloni G, Lai A (2016) Sustainability management and reporting: The role of integrated reporting for communicating corporate sustainability management. J Clean Prod 136:102–110

Stechemesser K, Guenther E (2012) Carbon accounting: A systematic literature review. J Clean Prod 36:17–38

* Steyn M (2014) Organisational benefits and implementation challenges of mandatory integrated reporting: Perspectives of senior executives at South African listed companies. Sustain Account Manag Policy J 5:476–503

* Strong PT (2015) Is integrated reporting a matter of public concern? J Corp Citizensh 60:81–100. https://doi.org/10.9774/gleaf.4700.2015.de.00008

* Stubbs W, Higgins C (2014) Integrated reporting and internal mechanisms of change. Account Auditing Account J 27:1068–1089

* Thomson I (2015) ‘But does sustainability need capitalism or an integrated report’: A commentary on ‘The International Integrated Reporting Council: A story of failure’ by Flower, J. Crit Perspect Account 27:18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2014.07.003

Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P (2003) Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag 14(3):207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

* Veltri S, Silvestri A (2015) The Free State University integrated reporting: A critical consideration. J Intellect Cap 16:443–462

* Vorster S, Marais C (2014) Corporate governance, integrated reporting, and stakeholder management: A case study of Eskom. Afr J Bus Ethics 8:31–57

* Zappettini F, Unerman J (2016) ‘Mixing’ and ‘Bending’: The recontextualisation of discourses of sustainability in integrated reporting. Discourse Commun 10(5):521–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481316659175

Zhang XJ (2012) Information relevance, reliability and disclosure. Rev Account Stud 17(1):189–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-011-9170-7

Zhou S, Simnett R, Green W (2017) Does integrated reporting matter to the capital market? Abacus 53:94–132

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J. Oll and S. Rommerskirchen declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oll, J., Rommerskirchen, S. What’s wrong with integrated reporting? A systematic review. NachhaltigkeitsManagementForum 26, 19–34 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00550-018-0475-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00550-018-0475-x