Abstract

Regorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, is effective in treating metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Hypertension is a frequently occurring adverse effect caused by regorafenib regardless of previous treatment with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors in almost all patients. We identified the risk factors associated with regorafenib-induced severe hypertension. Patients with mCRC (n = 100) who received regorafenib were evaluated retrospectively. The primary endpoint was the evaluation of the risk factors for grade ≥ 3 hypertension. The association between pre-existing hypertension at baseline and grade ≥ 3 hypertension symptoms was also assessed. Patients with pre-existing hypertension at baseline accounted for 55% of the total patients. The starting doses of regorafenib were 160 mg (49.0% of patients), 120 mg (29.0%), and 80 mg (22.0%). The incidence of grade ≥ 3 hypertension was 30.0%. The median time to grade ≥ 3 symptom development was 7 days (range: 1–56 days). Additional antihypertensive treatment was administered to 83.6% of patients who developed hypertension. Logistic regression analyses revealed that baseline pre-existing hypertension complications and previous anti-VEGF treatment for ≥ 700 days were independent risk factors for grade ≥ 3 hypertension development. Further analyses revealed that pre-existing hypertension before anti-VEGF treatment (primary hypertension) was significantly related to the symptom development (adjusted odds ratio, 8.74; 95% confidence interval, 2.86–26.72; P = 0.0001). Our study suggests that pre-existing primary hypertension and previous anti-VEGF treatment for ≥ 700 days are independent risk factors for regorafenib-induced severe hypertension. Deeper understanding of the symptom nature and management can significantly contribute to safer interventions, necessitating further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Regorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, exerts an inhibitory effect on several protein kinases associated with the regulation of tumor angiogenesis (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor [VEGFR] 1–3, TIE2), oncogenesis (KIT, RET, RAF1, BRAF, and BRAFV600E), and the tumor microenvironment (platelet-derived growth factor receptor [PDGFR] and fibroblast growth factor receptor [FGFR]) [1, 2]. It is also the first small-molecule multikinase inhibitor to provide survival benefits in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) [1, 2]. However, regorafenib administration frequently induces adverse effects such as hand-foot-skin reaction (HFSR), hypertension, liver dysfunction, diarrhea, fatigue, anorexia, proteinuria, and voice changes [1, 2]. A phase III trial on mCRC showed that 38% of patients had dose reduction, and 61% of them experienced dose interruption owing to severe symptoms [1].

Hypertension is one of the most frequently occurring adverse effects of regorafenib in mCRC treatment (30–60% of cases), regardless of previous treatment with VEGF inhibitors in almost all patients [1, 2]. It mainly manifests within 3 weeks from treatment initiation [3]. The mechanisms underlying this symptom are considered to be decreased nitric oxide (NO) production, increased endothelin-1, activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and capillary rarefaction, all of which are caused by the anti-VEGF effect [1, 4, 5]. Hypertension is related to cardiovascular events in patients receiving multikinase inhibitors, and, in general, it also induces renal events [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Risk factors associated with hypertension induced by multikinase inhibitors include pre-existing hypertension, older age, and higher body mass index (BMI) [12]. Additionally, pre-existing hypertension, antihypertensive drug use, older age, higher dosage, female sex, higher serum creatinine level, and presence of liver metastasis are associated with that by bevacizumab, which is the most representative anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody [5, 13,14,15,16,17]. However, a previous study on multikinase inhibitor-induced hypertension included a small number of patients with mCRC who received regorafenib and evaluated only anti-VEGF treatment-naive patients [12]. Patients with mCRC generally receive anti-VEGF agents such as bevacizumab, ramucirumab, and aflibercept beta as frontline treatment for a certain period [18], suggesting that patients’ profiles are quite different from those of patients with other malignancies in a real-world setting.

In the present study, we aimed to identify risk factors associated with regorafenib-induced severe hypertension in patients with mCRC.

Methods

Patients

Patients with mCRC who received regorafenib between May 2013 and March 2022 at Hokkaido University Hospital were retrospectively evaluated. All enrolled patients met the following baseline criteria: (1) age ≥ 20 years, (2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) score of 0 to 2, and (3) sufficient renal or liver function for treatment induction. Patients who had uncontrolled baseline hypertension (grade ≥ 3 symptoms), were not able to complete the first cycle of treatment due to progression disease and severe skin toxicity, and were transferred to another hospital during the treatment were excluded from the study. Patients with inadequate medical records were also excluded. The total number of patients was calculated based on the assumption that the incidence of grade ≥ 3 hypertension, which was defined as the primary symptom, would be 30%, and approximately three covariates were included in the multivariate analysis (10 events per variable) based on previous reports and our clinical experience [2, 19]. The present study was approved by the Ethical Review Board for Life Science and Medical Research of Hokkaido University Hospital (approval number:021–0141) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the STROBE statement. Given the retrospective nature of this study, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Treatment methods

Regorafenib was administered at an oral dose of 160 mg/day on days 1–21, every 4 weeks [1, 2]. Some patients received a reduced starting dose with a subsequent dose-escalation strategy (starting dose of 80–120 mg/day with weekly 40 mg escalation to 160 mg/day, if possible), which was in line with that mentioned in a previous study [20]. Treatment was discontinued according to the criteria stated on the medical package insert [21]. Antihypertensive drugs such as angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), calcium channel blockers, and diuretic drugs were administered to the patients to ameliorate the symptoms, at the physician’s discretion.

Survey of the incidence and severity of hypertension

All the required information was obtained from the patients’ medical records. Patients visited the hospital weekly during the first 2 months to undergo an evaluation of adverse effects. We strongly advised all patients to maintain a daily diary, which all patients wrote, provided by Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Home blood pressure by referring to the documented journal and in-hospital blood pressure were evaluated by physicians or pharmacists at every visit. Severity was graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0. For this study, hypertension was defined as the occurrence of any of the following conditions: (1) a diagnosis of hypertension as recorded in the medical records, (2) at least one antihypertensive medication prescription, and (3) blood pressure (home and visit) indicating CTCAE grade ≥ 2 according to the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology position paper [22, 23]. The incidence and severity of hypertension during the entire treatment period were evaluated. The primary endpoint was defined to reveal the risk factor(s) associated with the incidence of CTCAE grade ≥ 3 hypertension, as we considered that grade ≥ 3 symptoms are clinically problematic because they definitely require treatment with antihypertensive medication and suspension of regorafenib administration, as mentioned in a previous report [12].

Statistical analysis

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using logistic regression analysis to reveal the baseline independent risk factors for grade ≥ 3 hypertension development. For these analyses, we used the following covariates: sex, age, ECOG-PS score, clinical stage, KRAS status, body surface area, BMI, presence of liver metastasis, neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, liver dysfunction (grade ≥ 2 elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total bilirubin), renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance of < 60 mL/min), C-reactive protein elevation at baseline, dose reduction since treatment initiation, duration from the last anti-VEGF therapy to regorafenib initiation, duration of total pretreated anti-VEGF therapy, and presence of pre-existing hypertension, which is in line with previous reports [5, 12,13,14,15,16,17]. Variables that demonstrated potential associations with grade ≥ 3 hypertension incidence in the univariate logistic regression analysis (P ≤ 0.15) were input into the multivariable model. The incidence of grade ≥ 3 hypertension between specific patient groups was compared using Fisher’s exact probability method. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to estimate the optimal cutoff values of previous anti-VEGF treatment periods.

All data analyses were performed using JMP, version 14.0, statistical software (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Differences were considered statistically significant when P-values were less than 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, 100 patients with mCRC were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). Baseline patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Median patient age was 64 years (range; 28–83 years), BMI was 22.73 kg/m2 (14.95–30.39 kg/m2), and serum albumin levels were 3.8 g/dL (2.1–4.7 g/dL). Liver metastasis was seen in 66% of the patients. Median duration from the last anti-VEGF administration was 109 days (11–1554 days) and that of the total previous anti-VEGF treatment was 505 days (42–1916 days). Pre-existing hypertension at baseline was noted in 55% of the patients. The starting doses of regorafenib were 160 mg, 120 mg, and 80 mg in 49%, 29%, and 22% of patients, respectively. Median treatment duration was 56 days (range: 14–738 days).

Incidence and severity of hypertension

Data of the incidence and severity of hypertension during regorafenib treatment are shown in Table 2. The incidence of grade ≥ 3 symptoms was 30.0%, and that of all defined hypertension cases was 55.0%. The median time for grade ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 symptom development was 7 days from treatment initiation for both grades (range: 1–56 days for both grades). Additional antihypertensive treatment was administered to 83.6% of patients with regorafenib-induced hypertension. ARBs were the most common drugs administered (69.6% of patients receiving antihypertensive treatment), followed by calcium channel blockers (52.2%) and diuretics (8.7%).

Risk analysis of severe hypertension development

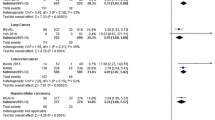

The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses to identify risk factors for the development of grade ≥ 3 hypertension are shown in Table 3. ROC curve analysis results revealed that the cutoff for total previous anti-VEGF treatment duration was 706 days, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.62, sensitivity of 58.6%, and specificity of 68.6%. Therefore, we set the cutoff for the previous anti-VEGF treatment period to 700 days. Results of logistic regression analysis revealed that baseline pre-existing hypertension complications and previous anti-VEGF treatment for ≥ 700 days were independent risk factors for grade ≥ 3 symptom development (Table 3A). Patients with hypoalbuminemia tended to experience grade ≥ 3 symptoms at a higher rate; however, the difference was not statistically significant. We further evaluated the relationship between the timing of pre-existing hypertension development (before or after the first anti-VEGF treatment) and the development of regorafenib-induced severe hypertension. Patients with pre-existing hypertension before anti-VEGF therapy, which indicates primary hypertension, had a significantly higher incidence of grade ≥ 3 regorafenib-induced hypertension than those without baseline hypertension and with pre-existing hypertension caused by previous anti-VEGF treatment (Fig. 2). Consequently, we performed multivariate analysis again using pre-existing primary hypertension before anti-VEGF treatment instead of all baseline pre-existing hypertension, which yielded the same results (adjusted odds ratio, 8.74; 95% confidence interval, 2.86–26.72; P = 0.0001 for primary hypertension, 4.59; 1.41–14.92; P = 0.01 for previous anti-VEGF treatment ≥ 700 days, Table 3B). By contrast, pre-existing hypertension caused by previous anti-VEGF treatment was not extracted as a factor (data not shown).

Discussion

Regorafenib administration induces hypertension and subsequent cardiovascular and renal events through its main mechanism of action. A meta-analysis suggested that patients receiving regorafenib have a significantly higher risk of hypertension development than those receiving best supportive care [4], even though previous anti-VEGF treatment had already targeted the VEGF-signaling pathways before its administration. Another study evaluated the factors associated with multikinase inhibitor-induced hypertension. A few patients with mCRC were included in that study. In addition, those who previously received anti-VEGF therapy were excluded [12]. Consequently, the factors may differ from results in the real-world mCRC treatment owing to pre-VEGF modifications. In the present study, we first identified the risk factors associated with regorafenib-induced severe hypertension development in real-world mCRC treatment.

The results showed that 55% of the patients experienced regorafenib-induced hypertension, including 30% of grade ≥ 3 cases. The incidence of grade ≥ 3 symptoms was higher than that reported in previous studies [1, 2]; as primary hypertension at baseline and previous anti-VEGF treatment duration of ≥ 700 days were associated with symptom development, there might have been more patients with risk factors in our study. In addition, similar results were obtained in a previous study [12]; the authors speculated that the potential reason is the evolution of the definition of hypertension severity with more detailed evaluation from CTCAE, version 3.0. Moreover, in the Japanese subgroup analysis of the CORRECT study, the incidence rate of all-grade hypertension was higher than that in the non-Japanese population, although severe symptoms appeared similarly [1, 2]. Previous studies on other kinase inhibitors have also shown a higher rate of hypertension development in the Japanese population [24,25,26]. Furthermore, regorafenib-administered Japanese patients have experienced higher rates of HFSR, proteinuria, thrombocytopenia, and lipase elevations than non-Japanese patients [2]. The detailed rationale remains unclear; as population pharmacokinetic analysis showed a similar 24-h area under the regorafenib-concentration curve between the Japanese and non-Japanese subpopulations [2], Japanese patients may show more sensitivity to multikinase inhibitor-induced adverse effects. Therefore, the results of the present study should be interpreted in light of this knowledge.

Pre-existing primary hypertension has been regarded as a factor for hypertension caused by multikinase inhibitors and bevacizumab [12,13,14]. The underlying mechanism is unknown, but it could be reasonable to speculate that higher baseline blood pressure levels in hypertensive patients could have affected the results, as hypothesized by Hamnvik et al. [12]. Wicki et al. also reported that pre-existing cardiovascular disease, other comorbidities, or other medications do not affect its incidence in bevacizumab-treated patients [13]. They concluded that underlying hypertension contributes to the sensitivity of patients to the prohypertensive effects of bevacizumab, irrespective of the actual antihypertensive therapy [13]. We are in complete agreement with their opinion. We further divided patients with primary hypertension before anti-VEGF treatment into those who did or did not develop hypertension due to previous anti-VEGF treatment and evaluated the incidence of regorafenib-induced hypertension, resulting in no difference (data not shown). Considering the results of the present study and those of previous reports, pre-existing primary hypertension before anti-VEGF treatment was significantly associated with regorafenib-induced severe hypertension development, whereas pre-existing hypertension induced by previous anti-VEGF treatment was not related to the symptoms.

Previous anti-VEGF treatment for a duration of 700 days or longer was also detected as an associated factor. This mechanism is unclear, as previous anti-VEGF treatment-induced hypertension was not associated with the development of grade ≥ 3 symptoms. The proportion of patients with baseline hypertension including primary or pretreated anti-VEGF-induced symptoms was not different between those with durations shorter and longer than 700 days (data not shown). In addition, we also evaluated the possibility of multicollinearity between the duration of total previous anti-VEGF treatment shorter and longer than 700 days and pre-existing hypertension values at baseline or prior to anti-VEGF treatment (primary hypertension), which resulted in a non-relationship (correlation coefficient of 0.11 and 0.06, respectively). Consequently, long-term inhibition of VEGF signaling pathways or anti-VEGF modification, regardless of hypertension development, may have affected the results. Further evaluation of this rationale will provide important insights.

It has been reported that bevacizumab- or multikinase inhibitor-induced hypertension occurs relatively at the early stage of the treatment (1–3 months) and stabilizes after a certain period [12, 13], which is consistent with our results. In particular, 70% of the patients experiencing grade ≥ 3 hypertension developed the symptoms within a week, while approximately 10% of the patients exhibited the symptoms after 1 month. Hence, it is necessary to monitor the symptoms and educate patients about its early development, particularly those with risk factors. By contrast, the duration from the last anti-VEGF treatment to regorafenib initiation did not affect the incidence of grade ≥ 3 hypertension; we set the duration as 28 days considering the previous treatment period. There was also no correlation between the interval from the last anti-VEGF treatment and grade ≥ 3 hypertension development, even though we further assessed the longer interval (until a year; data not shown). As the persisting duration of anti-VEGF and hypertensive effects from the last anti-VEGF agent administration remains unclear, further studies are required. Furthermore, BMI, which was suggested as a risk factor in a previous study evaluating multikinase inhibitors such as sunitinib, sorafenib, and pazopanib, was not extracted as a factor in this study, a finding that was consistent with the results of previous regorafenib evaluations [2, 12]. Interestingly, a regular starting dosage (initiation from 160 mg/day, with dose reduction depending on the adverse effects) was not associated with grade ≥ 3 hypertension development. A study that assessed the possibility of reducing the starting dose with subsequent dose escalation revealed that patients with dose-escalation dosing strategies developed hypertension similar to that in patients receiving a standard dosage [20]. Taguchi et al. reported that the blood concentrations of regorafenib and its metabolites differ in each individual, even at the same dosage, suggesting that its efficacy and safety should not be predicted only by its dosage [27]. As the correlation between blood concentrations of the drug and its efficacy or safety is not fully understood, further evaluation is needed.

It is important to manage hypertension caused by anti-VEGF treatment to ensure safer administration. van Dorst et al. [11] emphasized the importance of baseline cardiovascular risk stratification and screening, regular blood pressure monitoring, and appropriate drug intervention. Management guidelines for anti-VEGF treatment-induced hypertension have not been established; however, we generally follow the national guidelines for primary hypertension management [11]. ARBs or ACEIs are most frequently prescribed owing to their mechanism of action, although there is no evidence of their superior performance over others, and calcium channel blockers are often administered [4]. We assessed the additional antihypertensive treatment, which revealed that ARB administration or dose increase was initially conducted in patients without baseline hypertension or full dose of ARBs or ACEIs, with an adequate antihypertensive efficacy of 62.5%. Calcium channel blockers, with an adequate efficacy of 91.7%, were prescribed in cases of full doses of ARBs or ACEIs. However, ACEIs were not administered to any of the patients for the treatment. Furthermore, we additionally evaluated the influence of the type of baseline antihypertensive drug on the results in patients with pre-existing hypertension, which revealed no difference (data not shown). In contrast, evaluation of the relationship between the number of antihypertensive medications at baseline and regorafenib-induced hypertension development revealed that patients who started with ≥ 2 antihypertensive medications were more likely to develop regorafenib-induced severe hypertension than those who received 0–1 medication, although there was no difference in grade ≥ 2 symptoms (48.1% and 23.3%, P = 0.03, for grade ≥ 3 symptoms, and 59.3% and 53.4%, P = 0.66, for grade ≥ 2 symptoms). Considering these results, we recommend monitoring blood pressure cautiously and prescribing per-request drugs before regorafenib initiation in all patients with risk factors, especially those taking multiple antihypertensive medications. In addition, it is critical to establish the most effective strategy for anti-VEGF therapy-induced hypertension.

This study has some limitations. First, this study had a retrospective design and assessed a relatively small patient population from a single institution. Second, we pinned more importance on the evaluation of home-based blood pressure rather than in-hospital measurement, as some patients have masked hypertension or white-coat hypertension [13]. However, home-based monitoring can be influenced by the procedure and performance of a hemadynamometer. As we did not assess the methods for home blood pressure measurement used in this study, this might have affected the results. Finally, we did not evaluate regorafenib or its metabolite concentration in the blood. The trough concentration levels of N-oxide/desmethyl metabolites have been found to be significantly associated with the severity of hypertension or rash [28], which might have influenced the results. As a result, our preliminary findings should be validated in future research.

In conclusion, our study suggests that pre-existing primary hypertension and previous anti-VEGF treatment for 700 days or longer are independent risk factors for regorafenib-induced severe hypertension. A deeper understanding of the nature of the symptoms and their management significantly contributes to safer administration; hence, further studies are necessary.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, Siena S, Falcone A, Ychou M et al (2013) Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 381:303–312

Yoshino T, Komatsu Y, Yamada Y, Yamazaki K, Tsuji A, Ura T et al (2015) Randomized phase III trial of regorafenib in metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of the CORRECT Japanese and non-Japanese subpopulations. Invest New Drugs 33:740–750

Yamaguchi K, Komatsu Y, Satoh T, Uetake H, Yoshino T, Nishida T et al (2019) Large-scale, prospective observational study of regorafenib in Japanese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in a real-world clinical setting. Oncologist 24:e450-457

Wang Z, Xu J, Nie W, Huang G, Tang J, Guan X (2014) Risk of hypertension with regorafenib in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70:225–231

Dong M, Wang R, Sun P, Zhang D, Zhang Z, Zhang J et al (2021) Clinical significance of hypertension in patients with different types of cancer treated with antiangiogenic drugs. Oncol Lett 21:315

Aronow WS (2016) Optimal blood pressure goals in patients with hypertension at high risk for cardiovascular events. Am J Ther 23:e218-223

Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M et al (2007) Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356:125–134

Dobbin SJH, Petrie MC, Myles RC, Touyz RM, Lang NN (2021) Cardiotoxic effects of angiogenesis inhibitors. Clin Sci (Lond) 135:71–100

Chu TF, Rupnick MA, Kerkela R, Dallabrida SM, Zurakowski D, Nguyen L et al (2007) Cardiotoxicity associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Lancet 370:2011–2019

Weisstuch JM, Dworkin LD (1992) Does essential hypertension cause end-stage renal disease? Kidney Int Suppl 36:S33–S37

van Dorst DCH, Dobbin SJH, Neves KB, Herrmann J, Herrmann SM, Versmissen J et al (2021) Hypertension and prohypertensive antineoplastic therapies in cancer patients. Circ Res 128:1040–1061

Hamnvik OP, Choueiri TK, Turchin A, McKay RR, Goyal L, Davis M et al (2015) Clinical risk factors for the development of hypertension in patients treated with inhibitors of the VEGF signaling pathway. Cancer 121:311–319

Wicki A, Hermann F, Prêtre V, Winterhalder R, Kueng M, von Moos R et al (2014) Pre-existing antihypertensive treatment predicts early increase in blood pressure during bevacizumab therapy: the prospective AVALUE cohort study. Oncol Res Treat 37:230–236

Nishihara M, Morikawa N, Yokoyama S, Nishikura K, Yasuhara M, Matsuo H (2018) Risk factors increasing blood pressure in Japanese colorectal cancer patients treated with bevacizumab. Pharmazie 73:671–675

Price TJ, Zannino D, Wilson K, Simes RJ, Cassidy J, Van Hazel GA et al (2012) Bevacizumab is equally effective and no more toxic in elderly patients with advanced colorectal cancer: a subgroup analysis from the AGITG MAX trial: an international randomised controlled trial of capecitabine, bevacizumab and mitomycin C. Ann Oncol 23:1531–1536

Sun L, Ma JT, Zhang SL, Zou HW, Han CB (2015) Efficacy and safety of chemotherapy or tyrosine kinase inhibitors combined with bevacizumab versus chemotherapy or tyrosine kinase inhibitors alone in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Oncol 32:473

Brahmer JR, Dahlberg SE, Gray RJ, Schiller JH, Perry MC, Sandler A et al (2011) Sex differences in outcome with bevacizumab therapy: analysis of patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer treated with or without bevacizumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial 4599. J Thorac Oncol 6:103–108

Chiorean EG, Nandakumar G, Fadelu T, Temin S, Alarcon-Rozas AE, Bejarano S et al (2020) Treatment of patients with late-stage colorectal cancer: ASCO resource-stratified guideline. JCO Glob Oncol 6:414–438

Komatsu Y, Doi T, Sawaki A, Kanda T, Yamada Y, Kuss I et al (2015) Regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors following imatinib and sunitinib treatment a subgroup analysis evaluating Japanese patients in the phase III GRID trial. Int J Clin Oncol 20:905–912

Bekaii-Saab TS, Ou FS, Ahn DH, Boland PM, Ciombor KK, Heying EN et al (2019) Regorafenib dose-optimisation in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (ReDOS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 20:1070–1082

Stivarga tablets® [package insert on the internet]. Bayer Yakuhin., 2019. https://pharma-navi.bayer.jp/sites/g/files/vrxlpx9646/files/2020-11/STI_MPI_201909240_1568962296.pdf. accessed May 5, 2022

Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Munoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M et al (2016) ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC position paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC committee for practice guidelines: the task force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 37:2768–2801

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Rosei EA, Azizi M, Burnier M et al (2018) 2018 practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European society of cardiology and the European society of hypertension ESC/ESH task force for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 36:1953–2041

Ueda T, Uemura H, Tomita Y, Tsukamoto T, Kanayama H, Shinohara N et al (2013) Efficacy and safety of axitinib versus sorafenib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: subgroup analysis of Japanese patients from the global randomized Phase 3 AXIS trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol 43:616–628

Yamashita T, Kudo M, Ikeda K, Izumi N, Tateishi R, Ikeda M et al (2020) REFLECT-a phase 3 trial comparing efficacy and safety of lenvatinib to sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: an analysis of Japanese subset. J Gastroenterol 55:113–122

Kawai A, Araki N, Hiraga H, Sugiura H, Matsumine A, Ozaki T et al (2016) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study of pazopanib in patients with soft tissue sarcoma: results from the Japanese subgroup. Jpn J Clin Oncol 46:248–253

Taguchi D, Inoue M, Fukuda K, Yoshida T, Shimazu K, Fujita K et al (2020) Therapeutic drug monitoring of regorafenib and its metabolite M5 can predict treatment efficacy and the occurrence of skin toxicities. Int J Clin Oncol 25:531–540

Kobayashi K, Sugiyama E, Shinozaki E, Wakatsuki T, Tajima M, Kidokoro H et al (2021) Associations among plasma concentrations of regorafenib and its metabolites, adverse events, and ABCG2 polymorphisms in patients with metastatic colorectal cancers. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 87:767–777

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Participated in research design: YS and YK. Conducted experiments: YS. Performed data analysis: YS. Drafting of the manuscript: YS. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, the need for formal consent was waived by the Ethical Review Board for Life Science and Medical Research at Hokkaido University Hospital.

Consent to participate

Formal consent was not required for this type of study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

YS, YT, and MS have no conflicts of interest. YK reports receiving grants and personal fees from Ono, TAIHO, CHUGAI, Eli Lilly, Yakult, Bristol-Myers, Merck, Takeda, Novartis, Bayer, and Daiichi-Sankyo and grants from Iqvia outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Saito, Y., Takekuma, Y., Komatsu, Y. et al. Risk factor analysis for regorafenib-induced severe hypertension in metastatic colorectal cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 30, 10203–10211 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07381-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07381-z