Abstract

Purpose

Healthcare systems contribute to disparities in breast cancer outcomes. Patient navigation is a widely cited system-based approach to improve outcomes among populations at risk for delays in care. Patient navigation programs exist in all major Boston hospitals, yet disparities in outcomes persist. The objective of this study was to conduct a baseline assessment of navigation processes at six Boston hospitals that provide breast cancer care in preparation for an implementation trial of standardized navigation across the city.

Methods

We conducted a mixed methods study in six hospitals that provide treatment to breast cancer patients in Boston. We administered a web-based survey to clinical champions (n = 7) across six sites to collect information about the structure of navigation programs. We then conducted in-person workflow assessments at each site using a semi-structured interview guide to understand site-specific implementation processes for patient navigation programs. The target population included administrators, supervisors, and patient navigators who provided breast cancer treatment-focused care.

Results

All sites offered patient navigation services to their patients undergoing treatment for breast cancer. We identified wide heterogeneity in terms of how programs were funded/resourced, which patients were targeted for navigation, the type of services provided, and the continuity of those services relative to the patient’s cancer treatment.

Conclusions

The operationalization of patient navigation varies widely across hospitals especially in relation to three core principles in patient navigation: providing patient support across the care continuum, targeting services to those patients most likely to experience delays in care, and systematically screening for and addressing patients’ health-related social needs. Gaps in navigation across the care continuum present opportunities for intervention.

Trial registration

Clinical Trial Registration Number NCT03514433, 5/2/2018

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Despite significant decreases in cancer mortality since the 1990s [1], racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer mortality and timely treatment outcomes persist and may have widened for certain groups [2]. The death rate for Black women with breast cancer is almost double that of white women [2]. Women who identify as Hispanic/Latina have worse outcomes than their non-Hispanic/Latina counterparts [3]. Women who are publicly insured or have a primary language other than English are also at risk for poor outcomes [4,5,6], partly due to lack of access to timely cancer diagnosis and treatment caused by barriers to care [7,8,9].

Patient navigation is an evidence-based approach that is intended to address these patient barriers to receipt of timely, quality care and to improve patient experiences in the healthcare system, particularly among under-served populations [10, 11]. Patient navigation is a patient-centered care coordination model that uses clinical professionals or non-clinical healthcare workers who are integrated into the healthcare team to work one-on-one with patients through the cancer care continuum [9, 10, 12], and evidence supporting its effectiveness has grown [8]. Patient navigation increases cancer screening rates [13] and improves patient satisfaction and the timeliness of treatment initiation [9]. For example, the National Cancer Institute-supported Patient Navigation Research Program enrolled over 10,000 patients with abnormal cancer screening and 2000 with a new cancer diagnosis. This multi-site clinical trial demonstrated the benefit of navigation on timely initiation of cancer care and greater guideline-concordant care [5, 14,15,16,17,18]. Importantly, the trial demonstrated the impact of navigation was greatest among Black participants and those with health-related social needs [4, 17].

Despite heterogeneity in navigation programs, there are three common goals supported by the literature: provide patient support across the care continuum, target services to those patients most likely to experience delays in care, and systematically screen for and address patients’ health-related social needs [10, 19, 20]. The navigator role itself, however, can take many different forms. Breast cancer navigation programs may help patients follow-up with abnormal screening results, coordinate patients’ care through their cancer treatments with the goal of ensuring the completion of care in a timely manner, connect patients with survivorship support groups, and help patients advocate for themselves [10, 12]. Navigator activities range from assisting patients with insurance issues, transportation needs, scheduling appointments, or connecting patients with resources for other identified social needs [8]. They may also perform a range of services such as providing emotional support for the patient, coaching, and facilitating communication between the patient and the care team. This variability reflects the need for navigation to be adaptable to the institution and the patient population it serves, rather than prescriptive [21]. The literature assessing navigation services is weighted toward screening and diagnosis, and the lack of recent evidence on navigation services offered during breast cancer treatment limits the ability of best practices in navigation to be translated into clinical practice and evaluated for these programs’ effectiveness in mitigating health disparities, particularly at a regional level [16].

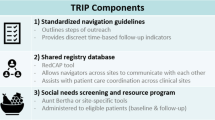

In Boston, Massachusetts, all academic cancer care hospitals have patient navigation services, yet, like many other cities nationally, the city continues to see disparities in breast cancer mortality based on race/ethnicity, language, and insurance status [1, 3,4,5,6]. As part of the pre-implementation work for the Translating Research Intro Practice (TRIP) study [22, 23], we provide an assessment and description of the variability of navigation programs available to women (as of 2017) undergoing treatment for breast cancer in the City of Boston.

Methods

Mixed methods data collection was conducted as formative work to inform the implementation of a large pragmatic trial, Translating Research Into Practice: A Regional Collaborative to Reduce Disparities in Breast Cancer Care (TRIP), a coordinated patient navigation delivery model across six hospitals in Boston, MA [22].

Data sources and collection

The data sources include a web-based survey of navigation program characteristics and in-person workflow assessments delivered as semi-structured interviews. The research team used a combination of the literature and expert consensus to develop the data collection tools [23]. Data were collected during the formative phase of the TRIP study to inform study implementation.

The Boston Breast Cancer Equity Coalition [24] is a stakeholder-engaged partnership from which this research emerged, and the Coalition identified breast oncology staff at each of the six sites to serve as clinical champions [25] for the study implementation; these individuals were invited to complete the survey. These clinicians were selected based on their high level of involvement with and oversight of their respective institutions’ breast oncology navigation programs. The web-based surveys used Qualtrics software and allowed clinical champions to describe the staffing composition of the navigation program (Appendix), which later served as the study sample of interest for the workflow assessment.

A team of two to three study investigators conducted in-person site visits to present the research study to relevant stakeholders at each site and elicit feedback from the multidisciplinary teams. These meetings concluded with a 60–90 min semi-structured workflow assessment group interview to understand the interrelated steps in each site’s existing patient navigation process. We conducted the workflow assessment with the breast oncology navigation team at each site, which typically consisted of patient navigator(s), patient navigator supervisor(s), and the site’s clinical champion(s) [26].

Measures

The survey assessed three main domains of patient navigation: (1) program characteristics, infrastructure of existing navigation program, including staff composition and funding; (2) cancer care continuum, systems and processes for identifying and following patients through treatment; and (3) systematic screening, existing processes for identifying addressing patients’ health-related social needs. The survey contained both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The survey results informed the development of the semi-structured interview guide used in the workflow assessment, which also focused on these key navigation domains and activities [27].

Analysis

Study members utilized a deductive coding approach based on the domains assessed in the survey and analyzed open-ended responses from the survey to categorize program characteristics and navigation services at each site, while closed-ended responses from the survey were analyzed using an informal content analysis approach. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. A team of two study members (NC, SH) then coded and analyzed the interviews to categorize program characteristics and navigation services at each site. The data from the workflow assessments were combined with the survey data to create a description of each site’s navigation activities by domain.

Results

Seven individuals completed the survey (sites determined who filled out the surveys). One to four individuals from each clinical site participated in the workflow assessment. Participants included patient navigators and their clinical supervisor, oncologists, nurses, and other clinical champions.

We identified wide variation in the operationalization of patient navigation across the six sites relative to the core principles of navigation. Table 1 presents an overview of our findings.

Program characteristics

All six sites stated that they provided patient navigation services for women with breast cancer. Four of the six sites utilized non-clinical staff, one site had RN level navigators, and one site used a social worker and nurse practitioner to perform navigation-related functions. Reporting structures varied in terms of who supervised the navigators. Lay navigators were under the supervision of clinicians. The nurse navigators were embedded within a surgical oncology department and supervised by breast surgeons. Three sites’ navigation programs were funded exclusively through grants; two sites had a combination of hospital operating budget funding, grants, and philanthropy; one site was funded entirely through the operating budget.

Scope of navigation

There was heterogeneity in the scope of navigation services offered across the six sites, leaving gaps in navigation services provided along the cancer care continuum (see Fig. 1). Some navigation programs started in the screening phase, while others did not engage patients until a specified stage of their treatment, usually treatment initiation after diagnosis was confirmed. At some sites, a combination of patient navigators and other staff members helped patients coordinate their care during different phases of treatment; others used one navigator to guide the patient through multiple phases of the care continuum. Sites varied in the extent of services they offered, who was eligible for those services, how patients were identified to receive navigation, and how frequently the navigator interacted with the patients. At several sites, all patients were eligible for navigation services. Some sites emphasized in-person navigation—where the navigator would accompany patients to medical appointments—while others relied more heavily on telephone encounters; this sometimes also varied within sites depending on the patient’s phase of treatment. None of the sites had a system for tracking patients who transferred care to another site or received treatment at multiple sites.

Identifying and addressing barriers to care

None of the sites had a process for systematically assessing health-related social needs for all breast cancer patients. Three sites screened some patients, but criteria for which patients received screening were unclear, and no tools for conducting standardized assessments existed. At one site, patients were referred to navigation services when other members of the care team identified a problem (for example, numerous missed appointments because of unreliable transportation). Among those sites that did screen some of their patients, access to food, ability to pay utilities, child and elder care responsibilities, and transportation were the most commonly asked domains. Systems for addressing patients’ health-related social needs, regardless of how the care team became aware of those needs, also varied; some sites had handouts with a list of service organizations, others referred patients to a social worker.

Discussion

Despite widespread evidence of navigation best practices, this study documents significant variation in how navigation is implemented across oncology practices in academic medical centers in Boston. While all sites reported having navigation program, there was little consistency of the roles, activities, and processes used in navigation. With regard to the three core principles of navigation—supporting patients across the care continuum, targeting services to patients most at risk for delays in treatment, and systematically screening for and addressing health-related social needs—we identified many gaps. The payor mix and patients served differ across these hospital systems, which may explain some of the variability—as both patient needs and available hospital resources may differ, so too may the structure of navigation programs.

The one commonality of all the navigation programs across the city of Boston was the navigators themselves, who are dedicated to support their patients during their cancer care. The surveys and workflow assessments, however, also revealed three types of gaps: (1) a lack of care across the treatment spectrum with multiple hand-offs or fragmentation of navigation (see Fig. 1); (2) a lack of standardization in which patients should be targeted for navigation services; and (3) a lack of standardization for how to identify patients’ social needs and how to address identified needs.

Identifying patients at high risk and in need of navigation services is the initial step of the care coordination model. At four of the six sites, all patients were eligible for navigation services. Navigation is most effective in addressing equity when it targets those women most at risk for delays in care [4]. Especially in the context of scarce resources, navigation services should be targeted toward patients who are most at risk for delays in care. Variability also existed in what phases of breast cancer care offered navigation services (Fig. 1), and those gaps represent risk areas for delays in care. One potential reason for this variability is the range in patient populations, which vary in race, ethnicity, and SES, served by the various sites.

Patient navigation was conceptualized to provide care coordination with a multidisciplinary team [10]. To that end, patient navigation should be understood as a process involving many members of the healthcare team and not as the role of an individual navigator. While five out of the six sites had individuals with the title navigator, all had other individuals—clinicians, social workers, resources specialists—involved in the process of navigation. In terms of staffing, the placement of navigators has an impact on the services offered. Navigators embedded within a clinical department may be able to more easily communicate with the clinical care team, but once that treatment module has ended, it may be unclear who will continue with the patient’s case (Fig. 1).

To meet the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) 2016 accreditation standards, oncology programs are required to have a patient navigation program aimed at addressing barriers to care and disparities [20]. The criteria are broad and allow that sites’ navigation processes, informed by community needs assessments conducted every three years, should “address healthcare disparities and barriers to cancer care” and provide “resources to address identified barriers … either on-site or by referral” [28]. Flexibility is embedded within this definition, to allow programs to be responsive to the needs of their local patient population. Having core processes in navigation programs, however, may help improve patient care at both the individual and the population level and is particularly important for addressing the persistent disparities in advanced stage disease [2, 16]. The guidelines were updated in 2020 and have changed significantly [29]. Identifying patients most at risk for delays in treatment presents an opportunity for hospital systems to consider the unique needs of the communities they serve. There has been a broader movement in healthcare to systematically screen for and address social determinants of health (SDOH), such as food insecurity and housing instability [30]. Literature suggests the importance of using standardized social needs assessments to proactively address patients’ barriers to care and improve health outcomes [31, 32]. A system that proactively screens for SDOH and follows up on addressing those needs has the potential to mitigate or remove barriers to treatment before they arise, rather than waiting until those barriers (lack of transportation, lack of childcare) manifest through interrupted treatment.

Our study is limited by the fact that we did not have complete data on all sites. Indeed, the difficulty encountered in obtaining full data on these patient navigation programs points to the challenges we identified. Other limitations to our study include a focus on only one type of cancer (breast cancer) and within one urban area with a focus on academic healthcare systems only. Our findings may not reflect the status of navigation in suburban or rural settings, or those provided in community hospitals. The differences of personnel and providing support for social needs and care progression within each healthcare system may have resulted in incomplete capture of all processes at any institution. However, this limitation is mitigated by the collaboration with clinical personnel at each organization to identify the key members of the support team for patients with breast cancer at each institution.

Conclusion

This investigation identified considerable variability of navigation programs available to women undergoing treatment for breast cancer in Boston. Navigation best practices indicate that such programs should be tailored to fit the needs of the local patient population, as a community-centered intervention [10, 33], while also integrating common elements that evidence suggest are critical to improving outcomes. Our findings identified both the necessary local tailoring to the circumstances of specific hospitals and the patients they serve as well as some gaps in the provision of common evidence-based elements. The systematic assessment approach used in this study demonstrates an approach to understanding patient navigation services that can be used to standardize programs while still meeting the needs of the most vulnerable patients [22].

References

Byers T (2010) Two decades of declining cancer mortality: progress with disparity. Annu Rev Public Health 31:121–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.121208.131047

DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, Newman LA, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A et al (2019) Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69:438–451. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21583

Ramirez A, Perez-Stable E, Penedo F, Talavera G, Carrillo JE, Fernández M et al (2014) Reducing time-to-treatment in underserved Latinas with breast cancer: the six cities study. Cancer 120:752–760. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28450

Rodday AM, Parsons SK, Snyder F, Simon MA, Llanos AAM, Warren-Mears V et al (2015) Impact of patient navigation in eliminating economic disparities in cancer care. Cancer 121:4025–4034. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29612

Ko NY, Snyder FR, Raich PC, Paskett ED, Dudley DJ, Lee J-H et al (2016) Racial and ethnic differences in patient navigation: results from the patient navigation research program. Cancer 122:2715–2722. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30109

Rocque GB, Williams CP, Jones MI, Kenzik KM, Williams GR, Azuero A et al (2018) Healthcare utilization, Medicare spending, and sources of patient distress identified during implementation of a lay navigation program for older patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 167:215–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4498-8

Hunt BR, Whitman S, Hurlbert MS (2014) Increasing Black:White disparities in breast cancer mortality in the 50 largest cities in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol 38:118–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2013.09.009

Bernardo BM, Zhang X, Hery CMB, Meadows RJ, Paskett ED (2019) The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of patient navigation programs across the cancer continuum: a systematic review. Cancer 125:2747–2761. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32147

Baik SH, Gallo LC, Wells KJ (2016) Patient navigation in breast cancer treatment and survivorship: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 34:3686–3696. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5454

Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL (2011) The history and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 117:3539–3542. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26262

Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, Darnell JS, Dudley DJ, Fiscella K et al (2014) Impact of patient navigation on timely cancer care: the patient navigation research program. J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju115. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju115

Braun KL, Kagawa-Singer M, Holden AE, Burhansstipanov L, Tran JH, Seals BF et al (2012) Cancer patient navigator tasks across the cancer care continuum. J Health Care Poor Underserved 23:398–413. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2012.0029

Medina-Jaudes N (2017) Patient navigation effectiveness on improving cancer screening rates: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Battaglia TA, Bak SM, Heeren T, Chen CA, Kalish R, Tringale S et al (2012) Boston patient navigation research program: the impact of navigation on time to diagnostic resolution after abnormal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol 21:1645–1654. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0532

Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, Dudley DJ, Fiscella K, Paskett E et al (2008) National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: methods, protocol, and measures - PubMed. Cancer 113:3391–3399

Gunn CM, Clark JA, Battaglia TA, Freund KM, Parker VA (2014) An assessment of patient navigator activities in breast cancer patient navigation programs using a nine-principle framework. Health Serv Res 49:1555–1577. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12184

Whitley EM, Raich PC, Dudley DJ, Freund KM, Paskett ED, Patierno SR et al (2017) Relation of comorbidities and patient navigation with the time to diagnostic resolution after abnormal cancer screening. Cancer 123:312–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30316

Ko NY, Darnell JS, Calhoun E, Freund KM, Kristin J (2014) Wells, Shapiro CL, et al. Can patient navigation improve receipt of recommended breast cancer care? Evidence From the National Patient Navigation Research Program. J Clin Oncol 32:2758–2764

Freeman HP (2006) Patient navigation: a community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ 21:S11–S14. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430154jce2101s_4

Commission on Cancer (2016) Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. American College of Surgeons, Chicago

Oncology Nursing Society (2017) Oncology nurse navigator core competencies. Oncol Nurs Forum 45:283. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.ONF.283

Battaglia TA, Freund KM, Haas JS, Casanova N, Bak S, Cabral H et al (2020) Translating research into practice: protocol for a community-engaged, stepped wedge randomized trial to reduce disparities in breast cancer treatment through a regional patient navigation collaborative. Contemp Clin Trials 93:106007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2020.106007

Freund KM, Haas JS, Lemon SC, White KB, Casanova N, Dominici LS et al (2019) Standardized activities for lay patient navigators in breast cancer care: recommendations from a citywide implementation study. Cancer 125:4532–4540. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32432

Boston Breast Cancer Equity Coalition. Boston Breast Cancer Equity Coalition. n.d. URL: https://bostonbcec.org (Accessed 28 April 2021).

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC (2009) Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 4:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

Casanova NL, LeClair AM, Xiao V, Mullikin KR, Lemon SC, Freund KM, et al. (In press) Development of a workflow process mapping protocol to inform the implementation of patient navigation programs in breast oncology. Cancer

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014) Chapter 3. Care coordination measurement framework. URL: https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/care/coordination/atlas/chapter3.html (Accessed 27 January 2021)

Gunn C, Battaglia TA, Parker VA, Clark JA, Paskett ED, Calhoun E et al (2017) What makes patient navigation most effective: defining useful tasks and networks. J Health Care Poor Underserved 28:663–676. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2017.0066

American College of Surgeons (2021) Optimal resources for cancer care: 2020 Standards

Garg A, Byhoff E, Wexler MG (2020) Implementation considerations for social determinants of health screening and referral interventions. JAMA Netw Open 3:e200693. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0693

Page-Reeves J, Kaufman W, Bleecker M, Norris J, McCalmont K, Ianakieva V et al (2016) Addressing social determinants of health in a clinic setting: the WellRx pilot in Albuquerque, New Mexico. J Am Board Fam Med 29:414–418. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150272

Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, Laves E, Burns AR, Amaya A et al (2016) Effects of social needs screening and in-person service navigation on child health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 170:e162521–e162521. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2521

Association of Community Cancer Centers (2009) Cancer care patient navigation: a practical guide for community cancer centers. Assoc Community Cancer Cent.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the partnership of TRIP’s stakeholders and community organizations: Boston Patient Navigator Network, Boston Breast Cancer Equity Coalition, Boston Public Health Commission: Pink & Black, Massachusetts Department of Public Health: Office of Community Health Workers; The National Center to Advance Translational Science, the Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI), University of Massachusetts CTSI, the Harvard CTSI, Tufts CTSI; our partner institutions Boston Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, Tufts Medical Center, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Dana Farber Cancer Institute; and finally the TRIP Consortium and our patient navigators.

Translating Research Into Practice (TRIP) Consortium

-

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Ted A. James MD, Susan McCauley RN, Ellen Ohrenberger RN BSN, JoEllen Ross RN BSN, Leo Magrini BS)

-

Boston Breast Cancer Equity Coalition Steering Committee (Susan T. Gershman MS MPH PhD CTR, Mark Kennedy MBA, Anne Levine MEd MBA, Erica T. Warner ScD MPH)

-

Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Cheryl R. Clark MD ScD)

-

Boston Medical Center (William G. Adams MD, Sharon Bak MPH, Nicole Casanova BA, Katie Finn BA, Christine Gunn PhD, Naomi Y. Ko MD, Ariel Maschke MA, Katelyn Mullikin BA, Laura Ochoa BA, Christopher W. Shanahan MD MPH, Samantha Steil BA, Tracy A. Battaglia MD MPH, Victoria Xiao BS)

-

Boston University (Howard J. Cabral PhD MPH, Clara Chen MHS, Carolyn Finney BA, Christine Lloyd-Travaglini MPH, Stephanie Loo MSc)

-

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Magnolia Contreras MSW MBA, Rachel A. Freedman MD MPH, Yoscairy Raymond BSW CCHW, Deborah Toffler MSW LCSW)

-

Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (Karen Burns White MS)

-

Equal Hope (Anne Marie Murphy PhD)

-

Massachusetts General Hospital (Carmen Benjamin MSW, Beverly Moy MD, Jennifer S. Haas MD MPH, Caylin Marotta MPH, Aileen Navarrete BA, Sanja Percac-Lima MD PhD, Emma Whited BA, Amy J Wint MSc)

-

Tufts Medical Center (Karen M. Freund MD MPH, William F. Harvey MD MSc, Danielle Krzyszczyk BA, Amy M. LeClair PhD MPhil, Susan K. Parsons MD MRP, Feng Qing Wang BA)

-

University of Massachusetts Lowell (Serena Rajabiun MA MPH PhD)

-

University of Massachusetts Medical School (Stephenie C. Lemon PhD)

NOGA

-

Award Number U01TR002070

-

The National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences

-

The Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research of the National Institutes of Health

-

NIH CTSA Awards

-

Harvard: UL1TR002541

-

Tufts: ULTR002544

-

Boston University: UL1TR001430

-

University of Massachusetts Medical School: UL1TR001453

American Cancer Society #CRP-17-112-06-COUN

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01TR002070. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under the Harvard University CTSA Award Number UL1TR002541, Tufts University CTSA Award Number UL1TR002544, Boston University CTSA Award Number 1UL1TR001430, and University of Massachusetts CTSA Award Number UL1 TR001453-03.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Amy M. LeClair: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review, editing, project administration

Tracy A. Battaglia: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing-review, editing

Nicole L. Casanova: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review, editing, project administration

Jennifer S. Haas: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing-review, editing

Karen M. Freund: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing-review, editing

Beverly Moy: Conceptualization, resources, validation, final review

Susan K. Parsons: Conceptualization, resources, validation, final review

Naomi Y. Ko: Conceptualization, resources, validation, final review

JoEllen Ross: Investigation, writing-review, editing

Ellen Ohrenberger: Investigation, writing-review, editing

Katelyn R. Mullikin: Writing-review, editing

Stephenie C. Lemon: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing-review, editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The present study received institutional review board approval from the Boston University Medical Center/Boston Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB# H-37314). The study’s formative work, described in this paper, was given a Non-Human Subjects Research designation, as the goal was to create a generalizable protocol for navigation process planning and improvement.

Consent to participate

The study’s formative work was given a Non-Human Subjects Research designation, and therefore, participants were not required to be consented.

Consent for publication

The study’s formative work was given a Non-Human Subjects Research designation, and therefore participants, were not required to be consented.

Conflict of interest

Author Karen M. Freund received funding from the American Cancer Society: American Cancer Society #CRP-17-112-06-COUN. The authors have no other funding or conflicts of interest to report.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A. Clinical Advisory Panel Survey about Navigation Program

Appendix A. Clinical Advisory Panel Survey about Navigation Program

Name

Institution

Patient Navigation

-

1.

Does your hospital provide patient navigation for any patients with breast cancer care during active treatment?

Navigators

-

2.

Are there different navigators at different phases of care (e.g. screening, diagnostic care, cancer care?)

-

3.

About how many clinical FTE patient navigators are focused specifically on breast cancer patients undergoing active treatment

-

4.

What is the educational background of the navigator(s) at your practice involved with breast cancer patients?

-

5.

What criteria are used to determine which patients are offered patient navigators?

-

6.

Which is the most common point of the patient's care process when navigators are brought into care?

-

7.

How are the navigators at your practice assigned patients during active cancer treatment?

-

8.

What is the most common way navigators are assigned patients?

-

a.

By referral of clinicians (physicians, nurses, SW)

-

b.

From a list of new patients or referrals

-

c.

Tumor board

-

d.

Other

-

a.

-

9.

How many patients does each navigator typically follow?

-

10.

What is the most common method by which patients are contacted?

-

11.

Who supervises the navigators?

-

12.

Supervisor's background

-

13.

What department is the navigator appointed under?

-

14.

What funding sources pay for breast cancer navigators at your practice?

Navigation tools

-

15.

What tools do navigators use to keep track of who/what they are navigating?

-

16.

What tools do navigators use to decide which patient to work with on a day to day basis?

-

17.

What tools do navigators use to identify when a patient has not kept a scheduled appointment or test?

-

18.

Does anyone else (besides the patient navigator) track patients to make sure they return for care?

-

19.

How do navigators decide that a patient no longer needs navigation?

-

20.

How does your practice determine if patients have left your practice and transferred care to another health care system?

-

21.

Has your hospital implement sending ADT information on the Mass Information highway?

-

22.

Is there a timeline planned for implementing this?

Social Determinants of Health

-

23.

Do any breast cancer providers routinely screen for social determinants of health?

-

24.

Who does the screening for social determinants of health among breast cancer patients?

-

25.

Which patients are screened?

-

26.

When are patients screened?

-

27.

How often are patients screened?

-

28.

Which domains are patients screened for?

-

29.

How does your practice perform the screening?

-

30.

Which electronic platform/EMR/website does your practice use?

-

31.

Are referrals made based on these screenings?

-

32.

Which domains are prioritized?

-

a.

Employee assistance

-

b.

Child/elder are assistance/parenting

-

c.

Transportation

-

d.

Mental Health

-

e.

Domestic Violence

-

a.

-

33.

How does your practice refer patients for social determinants of health?

-

34.

How is the decision made on where to refer patients?

-

35.

Where does your practice get a list of resources for potential referrals?

-

36.

Do you have a system to track whether a patient has connected with a referral or needs further assistance?

-

37.

Who follows up with the patient after they are referred?

-

38.

If your practice is not currently screening, does your practice have any plans to start systematic screening in the next 12 months?

-

39.

Which domains do you plan to prioritize? Please rank the top 5 domains based on priority?

-

a.

Housing instability

-

b.

Education/literacy

-

c.

Child/elder care assistance/parenting

-

d.

Transportation

-

e.

Immigration

-

f.

Legal

-

g.

Physical Activity

-

h.

Addiction and recovery

-

i.

Mental Health

-

j.

Health insurance

-

k.

Domestic Violence

-

l.

Community Violence

-

m.

Food instability

-

a.

-

40.

How does your practice plan to perform the screening?

-

41.

Where does your practice plan to get a list of resources for potential referrals?

-

42.

Will you have a system to track whether a woman has connected with a referral or needs further assistance?

-

43.

Who will follow up with the patient after they are referred?

-

44.

Any other comments or features about your clinical setting or patient navigation program that you think might be relevant to the current project to implement a standard patient navigation process across all Boston hospitals?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

LeClair, A.M., Battaglia, T.A., Casanova, N.L. et al. Assessment of patient navigation programs for breast cancer patients across the city of Boston. Support Care Cancer 30, 2435–2443 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06675-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06675-y