Abstract

Purpose

Diagnosis of breast cancer and its treatment dramatically affects women’s psychological health. This study investigated the prevalence of depression and anxiety and their related factor in breast cancer women.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study with a sample of 120 women with breast cancer in Zahedan, Iran, 2020. Data were collected using instruments included: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34), Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), The adjustment to illness measurement inventory for Iranian women with breast cancer (AIMI-IBC). We analyzed the data using the ANOVA, independent sample t-test, Kruskal Wallis, Mann‐Whitney U test, Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients.

Results

The prevalence of depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer was 66.6% and 60%, respectively. A significant positive correlation was found between anxiety and depression and unmet psychological needs, care/support needs, and emotional turmoil coping strategy, while reasonable efforts and avoidance coping strategies and adjusting to disease were negatively correlated with anxiety and depression. Also, linear regression results indicated unmet psychological needs, emotional turmoil coping strategy, and a high level of depression predicted a high anxiety level. A lower level of depression was indicated by reasonable efforts strategy and less level of anxiety.

Conclusions

Women with breast cancer reported a high level of depression and anxiety in Zahedan, and clinicians should pay more attention to these patients’ psychological distress. Resolving the unmet need of patients, increasing social support, and using the right coping strategy have an essential role in breast cancer women’s psychological distress control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and one of the leading causes of cancer deaths worldwide [1, 2]. Diagnosis and subsequent treatment of breast cancer affect all aspects of the patient’s life, challenge the patient’s, and significantly impact a person’s physical and mental ability [3]. In addition to survival concerns, breast augmentation and impaired body image significantly negatively impact patients’ mental health and cause anxiety and depression [4, 5]. Previous studies have shown that breast cancer survivors experience high levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms [6, 7]. Supportive care is the provision of services necessary to live with cancer to meet various psychological, informational, physical, and care/support needs at all stages of the disease [8]. Evidence showed an association between unmet needs and psychological distress in breast cancer patients [9] and the most significant factors in unmet supportive care needs were levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms [10]. A previous study suggested that patients with higher levels of depressive symptoms reported higher levels of unmet needs in psychological, physical/daily living, patient care/support, and additional unmet care needs, compared to patients with lower levels of depressive symptoms [11].

Cancer patients use different coping strategies to deal with their disease’s physical and psychological challenges, significantly impacting patients’ psychological symptoms [12]. Patients sometimes use positive coping strategies such as controlling the disease, positive thinking, acceptance, social support, and sometimes using negative strategies such as forgetfulness or frustration and fear in dealing with the disease situation [13]. Patients who use a positive coping strategy have fewer psychological symptoms [14].

Psychological disorders in people with cancer are significantly affected by social support. Patients with good social support have fewer emotional and psychosocial problems and can better cope with their illness [15]. Previous studies showed that family, friends, hospitals, and organizations’ support could help to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety and social isolation in patients with breast cancer [16, 17]. Also, high levels of social support through functional and positive coping may relieve depressed and anxious symptoms in breast cancer patients. Therefore, patients with breast cancer should obtain social support and be educated on using functional coping strategies [18]. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of anxiety and depression and its association with coping strategies, social support, and unmet needs in women with breast cancer in Zahedan, Southeastern Iran.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was done from February to August 2020 in Zahedan, Southeastern Iran. All women with breast cancer who approached the clinical oncology department of Khatam-Al-Anbia hospital and the radiotherapy department of Ali-Ebne-Abitaleb hospital were recruited in this study. These two departments cover all cancer patients in Zahedan.

Inclusion criteria included confirmed breast cancer diagnosis for at least 1 month before starting this study, having age ≥ 18 years, not having any psychological disorders, and ability to respond to the questions. All breast cancer patients who met the inclusion criteria consented to participate in the study. In total, we recruited 120 patients for this study. Because in this study, most of the participants were illiterate or had primary education, a private interview in hospitals was conducted with all participants to ensure uniformity in data collection.

We used a questionnaire to collect socio-demographic and clinical factors of patients’ include age, marital status, education level, time of diagnosis, place of residence, employment status, disease stage, type of surgery, and type of treatment. Also, we assessed depression and anxiety, social support, coping strategies, illness adjustment, and supportive care needs as follows:

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score (HADS)

We assessed anxiety and depression levels using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [19]. HADS scale consists of 14 items and two subscales, depression (7 items) and anxiety (7 items). Each item was scored from 0 to 3, and subscores are on scales of 0–21. Scores ≤ 7 on each subscale indicate no anxiety or depression, while scores 8–10 indicate possible anxiety and depression cases, and scores ≥ 11 indicate probable cases of anxiety and depression. The questionnaire was validated into the Persian version of HADS in the Iranian population [20].

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)

We used the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) to measure perceived social support [21]. This questionnaire was developed by Zimet in 1988 and consisted of 12 items, which cover three subscales: family (4 items), friends (4 items), and significant others (4 items). Each item had a 5-point Likert-type response scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); higher scores indicate patients more perceived social support. The MSPSS has been used in a previous study in Iran and had shown good reliability and validity [22].

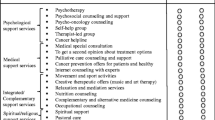

Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34)

The SCNS-SF34 instrument consists of 34-item and measures the patient’s level of need for help in five domains such as the psychological (10 items), health system and information (11 items), physical and daily living (5 items), care and support of patients (5 items), and sexuality (3 items). The patients responded to each item based on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = no need, 2 = no need/satisfied, 3 = low need, 4 = moderate need, and 5 = high need). The score range in each domain is from 0 to 100 that a higher score indicated higher levels of unmet needs [23]. A previous study showed a Cronbach alpha coefficient of above 0.9 for the Persian version of the questionnaire [24].

Coping strategies and degree of adjustment (AIMI-IBC)

We adopted the adjustment to illness measurement inventory for Iranian women with breast cancer (AIMI-IBC) to assess coping strategies and degree of adjustment. This instrument consists of 49 items and comprises three domains: emotional turmoil, reasonable efforts, and avoidance coping strategy. The emotional turmoil strategy emphasizes negative coping such as guilt, isolation, fear, anxiety, and role reduction. In comparison, reasonable efforts and avoidance strategies emphasize positive coping such as positive thinking, support, and self-distraction. A previous study showed that the AIMI-IBC was a valid instrument in women with breast cancer [25].

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test assessed the normality of the variables. The ANOVA, independent sample t-test, Kruskal Wallis, and Mann Whitney U test compared the mean scores of the anxiety and depression subscale among the categorical independent variables. Also, the post hoc analysis determined differences among means in the categorical variable. We performed Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation analyses to identify the association between psychological distress (anxiety and depression) with supportive care needs, social support, and coping strategies. The multiple linear regression analysis determined the predictors of anxiety and depression subscales after controlling the confounding variables. All variables associated with anxiety and depression in univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate model. We computed the R-squared value, standardization regression coefficient (β), and P-value in SPSS software package 19. The p-value of less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean (SD) age of the patients was 47.35 (SD = 10.67) years; most were married (75.8%), housewives (88.3%), and lived in urban (77.5%). 28.3% of the patients were illiterate, while 10.8% had a higher education level. The mean (SD) time of cancer diagnosis was 23.69 (20.38) months, and nearly 84% of patients were diagnosed with stage III and stage IV cancer. The majority of patients (94.2%) had received chemotherapy. Table 1 shows the participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics.

Patients who were housewives presented a higher level of depression (mean = 9.70, SD = 3.95) and anxiety (mean = 9.18, SD = 4.55) than employed patients. Also, results showed that patients who had been diagnosed with stage IV disease (mean = 11.21, SD = 3.88) had a higher level of depression compared to patients who had been diagnosed with stage III (mean = 8.79, SD = 3.61) and stage II disease (mean = 7.51, SD = 4.17) (Table 1).

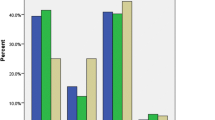

The mean (SD) of depression and anxiety in patients was 9.26 (4.1) and 8.88 (4.8), respectively. 26.7% and 29.2% of the patients were possible cases of anxiety and depression subscales, and 33.3% and 37.5% of patients were probable cases of anxiety and depression, respectively. Therefore, based on the cut-off point of depression and anxiety ≥ 8 [26], the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the study patients was 60% (95%CI: 51.2–68.7) and 66.6% (95%CI: 57.4–75), respectively (Table 2).

Table 3 reports the correlation of the depression and anxiety scores with supportive care needs scores, social support scores, coping strategies, and illness adjustment scores. The finding indicated that depression had a negative correlation with total social support and friends subscale score. In comparison, the results showed a significant positive correlation among patients who need help in psychological and care/support of patient domain with depression and anxiety. Also, reasonable efforts and avoidance coping strategies and adjustment to disease negatively correlated with depression and anxiety, while emotional turmoil coping strategy positively correlated.

Table 4 shows the predictors of the anxiety and depression subscale. According to results of the multiple linear regression analyses, depression (B = 0.4, P < 0.001), psychological domain (B = 0.02, P = 0.03), and emotional turmoil strategy (B = 4.2, P < 0.001) were significant predictors of anxiety subscale. With increasing depression and the need to help in the psychological domain and emotional turmoil, the anxiety subscale increases. This model explained 59% of the variance of the anxiety subscale (Adjusted R-squared = 0.59).

The predictors which had a statistically significant effect on depression were reasonable efforts strategy (B = − 4.23, P < 0.001), anxiety (B = 0.39, P < 0.001), and accounted for 45% of the variance of depression (adjusted R-squared = 0.45). The patients who used the reasonable efforts strategy had lower depression. On the other hand, a higher level of anxiety was associated with a higher level of depression.

Discussion

Anxiety and depression are among the most common psychological disorders observed in patients with breast cancer [27, 28]. This study evaluated anxiety and depression and their relationship with coping strategies and adjustment to illness, social support, and care/support needs in patients with breast cancer in Zahedan.

The prevalence of anxiety and depression in cancer patients in Zahedan was estimated to be 60% and 66.6%, respectively. A meta-analysis in Iran reported the prevalence of depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients 46.8% (95%CI: 33.8–59.9%) and 41.9% (CI: 95%): 30.7, 53.2), respectively [29, 30]. A study in Germany on breast cancer survivors using the HADS questionnaire showed that 22% of patients had severe to moderate depression, and 38% had severe to moderate anxiety [31]. A study of 226 cancer patients in Jordan showed that the prevalence of anxiety and depression was 43% and 67.6%, respectively [32]. Also, meta-analysis study on Chinese adults with cancer showed the prevalence of depression was 54.90% (from 20 to 89%) and the prevalence of anxiety was 49.69% (from 20 to 89.13%) [33].

A study examining the prevalence of anxiety and depression among the general population of Iran showed that the prevalence of anxiety and depression was 32.2 and 29%, respectively. In the present study, the prevalence of anxiety and depression was significantly higher than the general population [34].

This study found no relationship between marital status, age, level of education, stage of the disease, type of surgery, and treatment with anxiety and depression in patients. Patients who were housewives suffered more anxiety and depression than working patients, consistent with other studies’ results [32]. Depression was also more severe in patients with stage 4. Previous study research showed that breast cancer patients with more advanced diseases experience more depression [35]. It has also been shown that disease progression is a determining factor in mental disorders in breast cancer patients [31].

There was no association between treatment methods such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy and surgical interventions with anxiety and depression in this study. Previous studies have found a relationship between current treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgical intervention, and anxiety and depression [36, 37]. Because anxiety and depression cause impairment in cancer patients’ physical and mental functioning, the diagnosis and treatment of anxiety and depression are highly recommended [38, 39]. It has also been shown that low psychological distress in breast cancer patients may lead to more cancer resistance [40].

The present study showed that higher social support and friends support affect reducing patients’ depression. A previous study reported most depression cases among patients who had difficulty supporting their family, communicating with relatives, and communicating with others [32]. Even not accompanying a spouse to hospital follow-up can increase anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients [7]. Therefore, perceived social support is an essential factor in lower levels of psychological distress (anxiety and depression) and a better life quality [41].

Evidence shows that cancer patients mostly use active strategies such as religious coping, acceptance of the disease, coping with the illness, and planning [42]. These strategies positively affect these patients’ psychological health and health behaviors and make women more adaptable to their condition [43].

The present study showed that a higher level of coping with emotional turmoil was associated with a higher level of depression and anxiety. Simultaneously, a higher level of coping than reasonable effort, avoidance, and adjustment to illness reduces anxiety and depression. Some coping styles, especially active coping styles, may moderate the association between psychological stress and anxiety and depressive symptoms in women with breast cancer [44]. This study shows a significant relationship between unmet needs in psychology and support with psychological distress, which is consistent with other studies [9, 45]. A previous study showed that cancer patients’ unmet needs with anxiety, depression, and low quality of life have a significant relationship [46].

In this study, multivariate analysis showed that the predictors of depression were reasonable effort and anxiety strategies. On the other hand, an increased risk of anxiety was predicted in patients with depression who needed help psychologically and used an emotional turmoil strategy to cope with their illness. Therefore, psychological problems in patients with breast cancer may be closely related to coping styles [47]. Also, findings from the previous study showed that breast cancer patients with better pain coping strategies also had lower anxiety, fatigue, and depression levels. Therefore, pain coping interventions may help women with breast cancer feel less fatigue and psychological distress [48]. However, patients adopt different coping strategies to cope with their disease, chemotherapy treatment, and physical and emotional symptoms [14].

We must point out the limitation of this study. Due to the cross-sectional design, the prevalence of anxiety and depression and coping strategies at one point in time have been investigated. Therefore, the patterns of anxiety and depression prevalence and the application of coping strategies during cancer treatments have not been evaluated. A longitudinal design can assess the prevalence of anxiety and depression and coping strategies on multiple occasions during treatment and provide more clarify information.

Conclusions

This study’s findings indicated the high prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with breast cancer and these patients should obtain more attention in Zahedan. Interventions to reply to patients’ unmet needs, mainly psychological and care/support needs and raising social support, helping patients use positive coping strategies, and early diagnosis of the disease may improve breast cancer women’s psychological distress.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Shin HR, Boniol M, Joubert C, Hery C, Haukka J, Autier P et al (2010) Secular trends in breast cancer mortality in five East Asian populations: Hong Kong, Japan, Korea. Singapore and Taiwan Cancer science 101(5):1241–1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01519.x

Wondimagegnehu A, Abebe W, Abraha A, Teferra S (2019) Depression and social support among breast cancer patients in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Cancer 19(1):836. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6007-4

Suwankhong D, Liamputtong P (2016) Social support and women living with breast cancer in the south of Thailand. J Nurs Scholarsh 48(1):39–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12179

Dukes Holland K, Holahan CK (2003) The relation of social support and coping to positive adaptation to breast cancer. Psychol Health 18(1):15–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044031000080656

Li J, Lambert VA (2007) Coping strategies and predictors of general well-being in women with breast cancer in the People’s Republic of China. Nurs Health Sci 9(3):199–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00325.x

Wang F, Liu J, Liu L, Wang F, Ma Z, Gao D et al (2014) The status and correlates of depression and anxiety among breast-cancer survivors in Eastern China: a population-based, cross-sectional case–control study. BMC Public Health 14(1):326. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-326

Karakoyun-Celik O, Gorken I, Sahin S, Orcin E, Alanyali H, Kinay M (2010) Depression and anxiety levels in woman under follow-up for breast cancer: relationship to coping with cancer and quality of life. Med Oncol 27(1):108–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-009-9181-4

Shun S-C, Yeh K-H, Liang J-T, Huang J, Chen S-C, Lin B-R et al (2014) Unmet supportive care needs of patients with colorectal cancer: significant differences by type D personality. Oncol Nurs Forum. https://doi.org/10.5353/th_b5662750

Uchida M, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Sagawa R, Nakaguchi T, Endo C et al (2011) Patients’ supportive care needs and psychological distress in advanced breast cancer patients in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 41(4):530–536. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyq230

Liao Y-C, Liao W-Y, Shun S-C, Yu C-J, Yang P-C, Lai Y-H (2011) Symptoms, psychological distress, and supportive care needs in lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 19(11):1743–1751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-1014-7

Pérez-Fortis A, Fleer J, Sánchez-Sosa JJ, Veloz-Martínez MG, Alanís-López P, Schroevers MJ et al (2017) Prevalence and factors associated with supportive care needs among newly diagnosed Mexican breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 25(10):3273–3280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3741-5

Livneh H. Psychosocial adaptation to cancer: the role of coping strategies. Journal of rehabilitation. 2000;66(2).

Hajian S, Mehrabi E, Simbar M, Houshyari M (2017) Coping strategies and experiences in women with a primary breast cancer diagnosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev: APJCP 18(1):215. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.1.215

Saniah A, Zainal N. Anxiety, depression and coping strategies in breast cancer patients on chemotherapy. Malays J Psychiatry. 2010;19(2).

Kavitha R, Jayan C (2014) Role of social support on cancer distress among breast cancer patients. Guru J Behav Soc Scie 2(1):247–251

Hughes S, Jaremka LM, Alfano CM, Glaser R, Povoski SP, Lipari AM et al (2014) Social support predicts inflammation, pain, and depressive symptoms: longitudinal relationships among breast cancer survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 42:38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.12.016

Liu B, Wu X, Shi L, Li H, Wu D, Lai X et al (2021) Correlations of social isolation and anxiety and depression symptoms among patients with breast cancer of Heilongjiang province in China: the mediating role of social support. Nurs Open 8(4):1981–1989. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.876

Zamanian H, Amini-Tehrani M, Jalali Z, Daryaafzoon M, Ala S, Tabrizian S et al (2021) Perceived social support, coping strategies, anxiety and depression among women with breast cancer: evaluation of a mediation model. Eur J Oncol Nurs 50:101892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101892

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Ebrahimi M, Jarvandi S (2003) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-14

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 52(1):30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Salimi A, Joukar B, Nikpour R. Internet and communication: perceived social support and loneliness as antecedent variables. 2009.

McElduff P, Boyes A, Zucca A, Girgis A. Supportive Care Needs Survey: a guide to administration, scoring and analysis. Newcastle: Centre for Health Research & Psycho-oncology. 2004.

Abdollahzadeh F, Moradi N, Pakpour V, Rahmani A, Zamanzadeh V, Mohammadpoorasl A et al (2014) Un-met supportive care needs of Iranian breast cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 15(9):3933–3938. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.9.3933

Hajian S, Mehrabi E, Simbar M, Houshyari M, Zayeri F, Hajian P. Designing and psychometric evaluation of adjustment to illness measurement inventory for Iranian women with breast cancer. Iranian journal of cancer prevention. 2016;9(4). https://doi.org/10.17795/ijcp-5461

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52(2):69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

Vickberg S (2001) Fears about breast cancer recurrence: interviews with a diverse sample. Cancer Pract 9(5):237–243. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009005237.x

Schmid-Büchi S, Halfens RJ, Dassen T, Van Den Borne B (2008) A review of psychosocial needs of breast-cancer patients and their relatives. J Clin Nurs 17(21):2895–2909. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02490.x

Hashemi S-M, Rafiemanesh H, Aghamohammadi T, Badakhsh M, Amirshahi M, Sari M, et al. Prevalence of anxiety among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer. 2020:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-019-01031-9

Dianatinasab SMKM, Fararouei M, Moameri H, Pakzad R, Gharaei HA, Ghaiasvand R. Meta-analysis of high prevalence of depression among breast cancer survivors in Iran: calling community supportive care programs. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2019030

Mehnert A, Koch U (2008) Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res 64(4):383–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.12.005

Mosleh SM, Alja’afreh M, Alnajar MK, Subih M (2018) The prevalence and predictors of emotional distress and social difficulties among surviving cancer patients in Jordan. Eur J Oncol Nurs 33(35):40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2018.01.006

Yang Y-L, Liu L, Wang Y, Wu H, Yang X-S, Wang J-N et al (2013) The prevalence of depression and anxiety among Chinese adults with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 13(1):393. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-393

Mirzaei M, Ardekani SMY, Mirzaei M, Dehghani A (2019) Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among adult population: results of yazd health study. Iran J Psychiatry 14(2):137. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijps.v14i2.993

Montazeri A, Harirchi I, Vahdani M, Khaleghi F, Jarvandi S, Ebrahimi M et al (2000) Anxiety and depression in Iranian breast cancer patients before and after diagnosis. Eur J Cancer Care 9(3):151–157. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2354.2000.00219.x

Komachi MH, Kamibeppu K, Nishi D, Matsuoka Y (2012) Secondary traumatic stress and associated factors among Japanese nurses working in hospitals. Int J Nurs Pract 18(2):155–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172x.2012.02014.x

Vodermaier A, Linden W, MacKenzie R, Greig D, Marshall C (2011) Disease stage predicts post-diagnosis anxiety and depression only in some types of cancer. Br J Cancer 105(12):1814–1817. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.503

Tel H, Tel H, Doğan S (2011) Fatigue, anxiety and depression in cancer patients. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res 17(2):42–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npbr.2011.02.006

Reich M, Lesur A, Perdrizet-Chevallier C (2008) Depression, quality of life and breast cancer: a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 110(1):9–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-007-9706-5

Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Idler E, Bjorner JB, Fayers PM, Mouridsen HT (2007) Psychological distress and fatigue predicted recurrence and survival in primary breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 105(2):209–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-006-9447-x

Ng CG, Mohamed S, See MH, Harun F, Dahlui M, Sulaiman AH et al (2015) Anxiety, depression, perceived social support and quality of life in Malaysian breast cancer patients: a 1-year prospective study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 13(1):205. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0401-7

Benson RB, Cobbold B, Boamah EO, Akuoko CP, Boateng D. Challenges, coping strategies, and social support among breast cancer patients in Ghana. Advances in Public Health. 2020:NA-NA. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4817932

Kim J, Han JY, Shaw B, McTavish F, Gustafson D (2010) The roles of social support and coping strategies in predicting breast cancer patients’ emotional well-being: testing mediation and moderation models. J Health Psychol 15(4):543–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105309355338

Wang X, Wang S-S, Peng R-J, Qin T, Shi Y-X, Teng X-Y et al (2012) Interaction of coping styles and psychological stress on anxious and depressive symptoms in Chinese breast cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13(4):1645–1649. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.4.1645

Akechi T, Okuyama T, Endo C, Sagawa R, Uchida M, Nakaguchi T et al (2011) Patient’s perceived need and psychological distress and/or quality of life in ambulatory breast cancer patients in Japan. Psychooncology 20(5):497–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1757

Lisy K, Langdon L, Piper A, Jefford M (2019) Identifying the most prevalent unmet needs of cancer survivors in Australia: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 15(5):e68–e78. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.13176

Wang F, Liu J, Liu L, Wang F, Ma Z, Gao D et al (2014) The status and correlates of depression and anxiety among breast-cancer survivors in Eastern China: a population-based, cross-sectional case–control study. BMC Public Health 14(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-326

Reddick BK, Nanda JP, Campbell L, Ryman DG, Gaston-Johansson F (2006) Examining the influence of coping with pain on depression, anxiety, and fatigue among women with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 23(2–3):137–157. https://doi.org/10.1300/j077v23n02_09

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients that participated in this study. We also appreciated all the health care workers in the clinical oncology department of Khatam-Al-Anbia hospital and the Radiotherapy Department of Ali-Ebne-Abitaleb hospital.

Funding

This work is part of the corresponding author master’s thesis and was supported by the Zahedan University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HOA, SK, and AAM were involved in the study design.

SK and FSS were involved in the data collection.

MM and SK were involved in the data analysis.

HOA and Sk were involved in the manuscript preparation.

All authors have read and verified the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical considerations and consent to participate.

The ethics committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences approved this study (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1399.010). We explained the purpose of the study to all patients and obtained written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okati-Aliabad, H., Ansari-Moghadam, A., Mohammadi, M. et al. The prevalence of anxiety and depression and its association with coping strategies, supportive care needs, and social support among women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 30, 703–710 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06477-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06477-2