Abstract

Purpose

Healthy lifestyles are an important part of cancer survivorship, though survivors often do not adhere to recommended guidelines. As part of the co-design of a new online healthy living intervention, this study aimed to understand cancer survivors’, oncology healthcare professionals’ (HCP) and cancer non-government organisation (NGO) representatives’ preferences regarding intervention content and format.

Methods

Survivors, HCP and NGO representatives participated in focus groups and interviews exploring what healthy living means to survivors, their experience with past healthy living programs and their recommendations for future program content and delivery. Sessions were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically.

Results

Six focus groups and eight interviews were conducted including a total of 38 participants (21 survivors, 12 HCP, 5 NGO representatives). Two overarching messages emerged: (1) healthy living goes beyond physical health to include mental health and adjustment to a new normal and (2) healthy living programs should incorporate mental health strategies and peer support and offer direction in a flexible format with long-term accessibility. There was a high degree of consensus between participant groups across themes.

Conclusions

These findings highlight the need for integration of physical and mental health interventions with flexibility in delivery. Future healthy living programs should investigate the potential for increased program adherence if mental health interventions and a hybrid of delivery options were included.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite evidence to support healthy lifestyle choices following a cancer diagnosis [1, 2], survivors are not meeting recommended guidelines [3,4,5,6,7] with almost three-quarters of cancer survivors not meeting recommendations for physical activity [5,6,7] and a recent American study identifying that 39% of survivors reported no physical activity at all [4]. More than half of survivors are overweight or obese [4, 6] and only a minority are meeting recommended fruit and vegetable consumption [7]. The majority of respondents in an American study of post-treatment cancer survivors also identified a need/desire for more information on health promotion [8]. These findings highlight the ongoing need for interventions that support healthy living after cancer.

A number of interventions have been developed and trialled including programs administered in-person [9,10,11], and/or via telephone and workbook [12]. These programs have demonstrated improvements in physical activity, nutrition, weight loss, mental health, quality of life and symptom severity and interference [9,10,11,12]. However, they can be costly to run and may not cater to all consumer preferences [13], highlighting a need to explore alternative delivery modalities.

Online healthy living programs have the potential benefit of widespread dissemination [14], are capable of facilitating social networking and peer support [15, 16] and allow participants to access content at their own pace, which can increase engagement and completion rates [17]. The use of online delivery holds promise as being less resource intensive [18] and cost effective [19]. Although this is encouraging, there are relatively few studies examining online programs for cancer survivors and further research on their optimal mode of delivery and content is needed from both consumer and provider perspectives [18, 20].

As part of the co-design of an online intervention to support healthy living in cancer survivorship, the present study sought out to build upon a previous telephone-delivered Healthy Living after Cancer program [12]. To gain the perspective of individuals with exposure to a healthy living program, previous participants and nurse facilitators of this program were recruited. These perspectives were balanced by also recruiting HCP and NGO representatives who had not facilitated the program and who worked with cancer survivors regularly, as well as recruiting survivors who had not participated in the program. Involving HCP and NGO representatives who have regular contact with survivors (i.e. nurses, physiotherapists, support group representatives, etc.) offered increased breadth of views surrounding what cancer survivors want. The objectives of the present study were to gather the expertise of these cancer survivors, HCP and NGO representatives regarding their views on (a) what healthy living means to cancer survivors and (b) what cancer survivors would want a future healthy living program to look like in terms of content and format.

Methods

This paper follows the consolidation criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist [21].

Co-design framework

Research has indicated that failure to engage end-users in the design process is a strong contributing factor to low uptake and usage of an end-product [22]. Thus, to enhance adoption, compliance and implementation of our intervention we followed the Design Thinking Research Process [23] co-design framework, which follows current best-practice guidelines for intervention development [24]. The Design Thinking Research Process is a five-stage, iterative process which flows through phases of empathising, defining, ideating, prototyping and testing. This process has been applied in a variety of health care settings including cancer, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pain and mental health conditions [25]. Our first round of stakeholder engagement followed content analysis and focused on addressing the first two phases of the Design Thinking Research Process: empathise and define in order to start to identify what healthy living means to cancer survivors and how they would like a future healthy living program to look. Future research informed by the current funding will include further stages of Design Thinking Research Process.

Participant selection

Purposive sampling of participants included cancer survivors, HCP and NGO representatives. Adult survivors (18+ years) diagnosed with localised, non-metastatic cancer within the last 5 years and treated with curative intent were invited to participate. Survivors needed to have completed primary anticancer treatment (though those undergoing hormonal treatments were still eligible) and live in Australia. HCP were eligible if they treated cancer populations and included allied healthcare professionals. Eligible NGO representatives included staff, volunteers and representatives of cancer support organisations. NGO representatives were chosen due to having regular contact with cancer survivors.

Eligible participants included cancer survivors who had previously participated in, and nurses who had facilitated, Cancer Council SA’s (CCSA) Healthy Living after Cancer program, as well as survivors, HCP and NGO representatives who had not been a part of this program. Cancer Council is an Australian not-for-profit cancer support organisation with state-based centres. CCSA’s telephone-delivered Healthy Living after Cancer program aimed to increase exercise, improve healthy eating habits and support weight loss through twelve health coaching phone calls over a six-month period [12]. Participants who met eligibility criteria were invited to attend focus groups or individual telephone interviews in the event they could not travel to our focus group location or could not attend scheduled focus group dates.

Recruitment

Survivors were recruited via phone from early July 2019 through existing CCSA referral pathways, including their telephone information and support line, inviting individuals who had previously participated in Healthy Living after Cancer, contacting NGOs and clinical sites, and social media advertising. HCP and NGO representatives were recruited via phone and email through cancer support groups and non-profit organisations, as well as professional networks of the investigator team. HCP and NGO representatives included CCSA nurses who had previously facilitated Healthy Living after Cancer. Recruitment continued until saturation of themes was reached.

Setting and data collection

Focus groups and interviews were conducted between July and August 2019; were semi-structured; included a brief presentation on the history, content and limitations of the Healthy living after Cancer program; and followed a topic guide (see Table 1). Focus group participants were provided a copy of the existing Healthy Living after Cancer print workbook for reference and viewed the presentation about the program. Each focus group and interview started with questions to participants about what they thought healthy living meant to survivors and what goals cancer survivors would set for themselves and explored their previous experiences with healthy living programs. After that, initial discussion participants were presented with the Healthy Living after Cancer program content as an example of an intervention to prompt further feedback. The third section of discussion finished by asking participants if they were to have complete freedom in developing a new program what would it look like, how would it be delivered and what would it be called. Telephone interview participants were provided with the same presentation, including descriptions of the workbook’s content, verbally, for context. All focus groups and interviews were led by investigator AG, a master’s student in cognitive behavioural therapy, under the guidance of doctoral-level researcher JNM who assisted with group organisation and took notes during focus groups. Focus groups lasted approximately 60–90 min and telephone interviews lasted approximately 30 min. Participants provided signed written consent.

Data analysis

Focus groups and interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim by one investigator (AG) and underwent thematic analysis using qualitative data analysis software (NVivo 12.6.0). Two researchers (AG and JL) independently undertook thematic analyses of three of the 14 transcripts to establish a coding framework. These researchers met to compare and discuss the emerged coding framework and where there was disagreement between investigators, a third investigator was consulted (JNM). Through this process, consensus on the coding framework was established and AG coded the remaining transcripts. The emergent themes were organised by expansiveness (how many groups raised a theme); frequency (how many times a theme was raised across/within groups); and intensity (how strongly the beliefs and sentiments were endorsed). Themes that were not as prevalent, frequent or intensely raised are reported in supplementary materials (i.e. themes raised in less than three sessions, and/or with fewer than five references). Throughout the analysis process, team meetings including authors with extensive qualitative research experience (BK and LB) were conducted to diagram and finalise the structure of overarching messages, themes and subthemes.

This study was approved by the Cancer Council Institutional Research Review Committee (Project IER1904).

Results

Participants

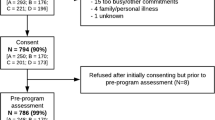

A total of 52 participants were recruited (n=33 cancer survivors, n=13 HCP, n=6 NGO representatives), of whom 38 participated (n=21 cancer survivors, n=12 HCP, n=5 NGO representatives). Attrition was due to inability to attend a scheduled focus group or interview (n=13) or failure to return a consent form (n=1).

Descriptive characteristics of all participant groups can be found in Table 2. Briefly, cancer survivors were mostly female (n=15 female, 71.4%) and aged between 42 and 88 years (M=56.0; SD=11.6). The most common diagnosis was breast cancer (n=12, 57.1%), with the remainder experiencing prostate (n=3, 14.3%), rectal (n=2, 9.5%) and other cancers (n=4, 19.1%). Most HCP and NGO representatives were nurses (n=7, 41.2%) or cancer support group members (n=3, 17.6%). The majority of survivors (n=17; 81.0%), and almost a-third of HCP and NGO representatives (n=5, 29.4%), had previously participated in or helped facilitate, the Healthy Living after Cancer program.

The study comprised three focus groups combining HCP and NGO representatives (HCP/NGO), three cancer survivor focus groups and eight individual telephone interviews with cancer survivors.

Themes

Themes were organised into two overarching messages, each with three themes and subsequent subthemes as presented in Fig. 1. The first overarching message encompassed that healthy living goes beyond physical health to include mental health and adjustment to a new normal. The second overarching message that emerged was new programs should add mental health and peer support and offer direction in a flexible format with long-term accessibility. (For frequency and expansivity of themes and subthemes, including illustrative quotes, see Table 3.)

Healthy living goes beyond physical health to include mental health and adjustment to a ‘new normal’

Healthy living was defined as having a good overall quality of life comprised three themes: physical health, mental health and adjustment to their ‘new normal’.

Healthy living means physical health

Physical health encompassed how survivors maintain their physical health through exercise, nutrition, weight management and alcohol and smoking cessation. Exercise was the most expansively and frequently referenced topic in focus groups and interviews, and often mentioned with nutrition—the next most frequently and broadly referenced topic. Within nutrition, survivors described the desire to improve their gut health.

Although weight management was only discussed in 2 focus groups and 3 interviews, it was frequently discussed within those sessions. Most references were alongside exercise and nutrition and were discussed with a sense of frustration in the need to gain or lose weight. Decreasing alcohol intake was mentioned evenly within survivors and HCP/NGO focus groups, though smoking cessation was only mentioned by HCPs.

Healthy living means mental health

Mental health was identified expansively and frequently by all groups as a key feature in what healthy living means to survivors. Within mental health, two subthemes emerged: motivation and concern for caregivers. Motivation was discussed in all survivor focus groups and mentioned in only one HCP/NGO focus group. Discussions related to finding it hard to get going, difficulties getting out of bed in the morning and lack of motivation for exercise. Concern for caregivers related to cancer survivors’ worry of how their families and friends were managing after their cancer.

Healthy living means adjusting to the ‘new normal’

The term ‘new normal’ was mentioned broadly and included three subthemes: managing post-treatment side effects, getting back to where survivors were before their cancer and setting individualised goals. Participants identified that in order to adjust to their ‘new normal’, survivors learned to manage post-treatment side effects. Specific post-treatment side effects included fatigue, which was mentioned equally by survivors and HCP/NGOs, whereas sleep quality was mentioned only by survivors.

A focus on getting back to where survivors were before their cancer was raised repeatedly and described returning to work and regaining pre-cancer health and abilities. Setting individualised goals was raised more by HCP/NGOs than cancer survivors with HCP stating that survivors wanted to make time for things they had always dreamt of doing, which was echoed by some survivors.

Healthy living programs should add mental health and peer support, and offer direction in a flexible format with long-term accessibility

When considering requirements for a future program, participants built upon their previous experiences with healthy living programs to highlight a strong desire for an added mental health component; a peer support component; and a tailored, flexible program with long-term accessibility. In exploring previous experiences with healthy living programs, all participants expressed appreciation for programs that addressed multiple health behaviours. The feedback from the Healthy Living after Cancer program content and delivery, based on the presentation, were mostly positive. Recommendations for future programs included frequent and expansive references to individualising the program, as well as a desire for an added mental health component, a recipes section and more exercise options.

Mental health should be a part of future programs

Both survivors and HCP/NGO representative participants strongly requested that future interventions address survivors’ mental health. Addition of a mental health component received the largest amount of discussion and support. There was intense agreement surrounding the need to address mental health before implementing other healthy living strategies. Mindfulness was frequently discussed as a desired strategy for addressing mental health.

Peer support should be a part of future programs

Peer support was intensely, expansively and frequently identified as an intervention component with two subthemes: a buddy system and case stories. A buddy system was described as a way of connecting participants to support and motivate one another to achieve their goals. Case stories were only mentioned in survivor interviews and described using survivors’ experiences of what enabled them to achieve their goals in order to help motivate participants.

New programs should be tailored and flexible with long-term accessibility

Survivors and HCP/NGO representatives identified a need for a hybrid of delivery options as it was repeatedly discussed that it is a personal decision as to how participants want to receive support. Hybrid delivery was discussed as including an offering of in-person, online, telehealth and workbook components. There were frequent mentions of starting a program with an introduction session to acclimate participants to the structure. In-person delivery received the most support with participants suggesting facilitating this through existing community resources (e.g. libraries, exercise groups) and offering support groups. Participants cited potential barriers to in-person delivery may include participants finding support groups overwhelming or daunting. Within online delivery, there were frequent positive comments surrounding a participant’s ability to access the information at any hour and utilising video content. There was intense, frequent and expansive discussion by participants of all ages surrounding older people not liking online platforms, the inability of some people to access the internet and the view that online programs lack personal connection. It was commonly mentioned that telephone delivery could serve to support mental health and could be widened to telehealth support generally if facilitated via videoconferencing. Participants expressed that a telehealth component promotes accountability and that a workbook is a useful physical resource, though workbooks were only mentioned by survivors. Long-term program accessibility was frequently discussed, and participants voiced a need for a program to provide individualised options and accountability to build and maintain motivation with their goals through strategies such as phone calls and progress tracking.

Discussion

The findings of this study build on existing research evidence that cancer survivors desire support with physical [1, 2, 8, 26] and mental health [8, 27,28,29,30,31], peer support [27, 32,33,34] and a flexible, tailored program [27, 32]. The novel contribution of this study is the recognition that these healthy living components need to be integrated into the study design, specifically incorporating mental health into the program content and not viewing it as only an outcome of the program.

Participants in our study emphasised that programs should address multiple health behaviours including explicitly incorporating and prioritising mental health. Statements that mental health intersected with healthy living were raised, unprompted, across participant groups, in all focus group sessions, and by survivors of various ages indicating a clear area of need. While it is well documented that exercise has beneficial impacts on cancer survivors’ mental health [35, 36], our study calls attention to a need for healthy lifestyle interventions to include tools specifically aimed to improve mental health. We are only aware of one healthy living program, Surviving and Thriving with Cancer [16], that has addressed specific mental health elements as part of a physical health intervention indicating a need for future programs to explore how to incorporate mental health alongside physical health needs. Participants in our study identified mindfulness as one approach to supporting survivor’s mental health. The frequent discussion of mindfulness as a way to support survivors’ mental health in future programs likely reflects emergence and popularity of mindfulness-based psycho-oncology interventions [37]. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining effects of mindfulness-based interventions in cancer survivors demonstrated small positive effects on anxiety [37, 38], depression [37, 38] and fatigue [38]. We are aware of only one study which incorporated mindfulness into an intervention addressing physical health which utilised mindfulness to support behaviour change rather than to address mental health [39]. Future multiple health behaviour change interventions might aim to further incorporate mindfulness as a mental health strategy.

While further research is needed to identify if sequential or simultaneous approaches are more efficacious and acceptable for multiple health behaviour change interventions [40], our findings also emphasised an importance of providing individualised options to allow survivors to choose how they engage and to select which elements are of importance to them. This desire for flexibility is consistent with an expressed clear desire for a hybrid of delivery options identified in our study. We are aware of only two programs in cancer survivorship which have utilised multiple delivery components and these studies utilised these components as steps of their program and not as parallel options to choose from [11, 41]. Specifically, the SUCCEED trial [11] used in-person group and individual counselling with follow-up telephone, email and newsletter components with uterine cancer survivors; and the ENERGY trial [41] with breast cancer survivors used an initial intensive phase of weekly in-person group meetings supplemented with telephone and/or email contact followed by a less intensive period adding a newsletter. Future interventions should explore how offering combinations of delivery options with choice in which delivery options participants engage in the program through impacts program engagement and cost of delivery.

Despite an online approach offering the benefit of a less resource intensive, more cost-effective delivery option with opportunity for widespread access; the findings from our first round of co-design indicated a preference against purely online delivery but rather a hybrid of online and face-to-face/telephone approach depending on user preferences. This finding highlights the importance of engaging end-users in the design process as beginning with understanding user preferences enables us to now direct our design towards better addressing our population’s needs. To the authors’ knowledge, few healthy living programs in cancer survivorship have utilised a co-design process. Previous studies utilised mixed methods [34] or user-centred design [42, 43] methodologies, typically via individual interviews with HCP and survivors [34, 42, 43]. The findings from these studies have some similarities to our own including older cancer survivors not wanting online programs [34, 42], lack of motivation as a barrier and desire for peer support [34]. A unique contribution of our study was inclusion of NGO representatives whose perspectives reflect frequent and enduring engagement with survivors.

The strengths of our study include our reliance on a co-design methodology and evidence-based co-design framework, engagement of cancer survivors and their health care providers in the development of our new program, recruitment of diverse cancer types, and our ability to build upon participants’ previous experiences with healthy living programs. A few limitations should also be noted. First, the project was titled ‘creating an online healthy living program’ in all communications with participants prior to focus groups and interviews, which may have predisposed discussion about online delivery. Furthermore, 81% of our cancer survivors and 39% of our HCP came with previous exposure to Healthy Living after Cancer which may have biased their definitions of healthy living. We attempted to balance this bias through inclusion of participants who had not engaged in the program and by delivering the presentation on the program after discussions of what healthy living means. Despite no limitations on cancer type or location, the sample was predominated by female breast cancer survivors and all participants were based in South Australia, thus limiting the generalisability of results. Lastly, our telephone interviews were unable to visually view the workbook content which likely decreased their ability to discuss the previous program though we aimed to counter this through verbally describing the program.

In conclusion, our findings identified that survivors, HCP and NGO representatives agree that for cancer survivors healthy living is defined as meaning more than their physical health needs, with the planned new intervention needing to address survivors’ mental health; and future healthy living interventions should incorporate peer support and offer choice and flexibility. Future interventions could explore hybrid delivery options with technology literacy in mind. While the results of our study created a ‘wish list’ of components for the program, these desires need to be balanced against resource-implications and longer-term program-sustainability requirements.

Data availability

Data unavailable for release due to risk of re-identification.

Code availability

n/a.

References

Cormie P, Zopf EM, Zhang X, Schmitz KH (2017) The impact of exercise on cancer mortality, recurrence, and treatment-related adverse effects. Epidemiol Rev 39(1):71–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxx007

Mehra K, Berkowitz A, Sanft T (2017) Diet, physical activity, and body weight in cancer survivorship. Med Clin North Am 101(6):1151–1165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.06.004

Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA) (2018) COSA position statement on exercise in cancer care. Sydney, NSW: Clinical Oncology Society of Australia.

Arem H, Mama SK, Duan X, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Ehlers DK (2020) Prevalence of healthy behaviors among cancer survivors in the United States: how far have we come? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 29:1179–1187. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1318

Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T (2005) Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol 23(34):8884–8893. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343

Eakin EG, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Lawler SP, Reeves MM, Heyworth JS, Fritschi L (2007) Health behaviors of cancer survivors: data from an Australian population-based survey. Cancer Causes Control 18(8):881–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-007-9033-5

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K (2008) Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol 26(13):2198–2204. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217

Beckjord EB, Arora NK, McLaughlin W, Oakley-Girvan I, Hamilton AS, Hesse BW (2008) Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: implications for cancer care. J Cancer Surviv 2(3):179–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-008-0055-0

Carlson LE, Doll R, Stephen J, Faris P, Tamagawa R, Drysdale E, Speca M (2013) Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cancer recovery versus supportive expressive group therapy for distressed survivors of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 31(25):3119–3126. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.47.5210

James EL, Stacey FG, Chapman K, Boyes AW, Burrows T, Girgis A, Asprey G, Bisquera A, Lubans DR (2015) Impact of a nutrition and physical activity intervention (ENRICH: Exercise and Nutrition Routine Improving Cancer Health) on health behaviors of cancer survivors and carers: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 15:710. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1775-y

von Gruenigen V, Frasure H, Kavanagh MB, Janata J, Waggoner S, Rose P, Lerner E, Courneya KS (2012) Survivors of uterine cancer empowered by exercise and healthy diet (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol 125(3):699–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.042

Eakin EG, Hayes SC, Haas MR, Reeves MR, Vardy JL, Boyle F, Hille JE, Mishra JD, Goode AD, Jefford M, Koczwara B, Saunders CM, Demark-Wahnefried W, Courneya KS, Schmitz KH, Girgis A, White K, Chapman K, Boltong AG, Lane K, McKiernan S, Millar L, O’Brien L, Sharplin G, Baldwin P, Robson EL (2015) Healthy Living after Cancer: a dissemination and implementation study evaluating a telephone-delivered healthy lifestyle program for cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 15:992. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-2003-5

Jones LW, Courneya KS (2002) Exercise counseling and programming preferences of cancer survivors. Cancer Pract 10(4):208–215

Lee MK, Yun YH, Park HA, Lee ES, Jung KH, Noh DY (2014) A web-based self-management exercise and diet intervention for breast cancer survivors: pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 51(12):1557–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.04.012

Kim AR, Park H-A (2015) Web-based self-management interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analyses. MedInfo 2015: eHealth-enabled health. IOS Press BV. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-564-7-142

Bantum EO, Albright CL, White KK, Berenberg JL, Layi G, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Plant K, Lorig K (2014) Surviving and thriving with cancer using a web-based health behavior change intervention: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 16(2):e54. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3020

Ritterband L, Bailey ET, Thorndike FP, Lord HR, .Farrel-Carnahan L, Baum LD (2012) Initial evaluation of an Internet intervention to improve the sleep of cancer survivors with insomnia. Psycho-Oncology 21:695–705

Goode AD, Lawler SP, Brakenridge CL, Reeves MM, Eakin EG (2015) Telephone, print, and web-based interventions for physical activity, diet, and weight control among cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 9:660–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0442-2

Elbert NJ, van Os-Medendorp H, van Renselaar W, Ekeland AG, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Raat H, Nijsten TEC, Pasmans SGMA (2014) Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of eHealth interventions in somatic diseases: a systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res 16(4):e110. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2790

Roberts AL, Fisher A, Smith L, Heinrich M, Potts HWW (2017) Digital health behaviour change interventions targeting physical activity and diet in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 11:704–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0632-1

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Roberts JP, Fisher TR, Trowbridge MJ, Bent C (2016) A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthc (Amst) 4(1):11–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.12.002

Woods L, Cummings E, Duff J, Walker K (2017) Design thinking for mHealth application co-design to support heart failure self-management. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-794-8-97

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2016) Community engagement: improving health and wellbeing and reducing health inequalities. London, UK: NICE.

Altman, M, Huang, TTK, & Breland, JY (2018) Design thinking in health care. Prev Chronic Dis. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180128

Kent EE, Arora NK, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Forsythe LP, Hamilton AS, Oakley-Girvan I, Beckjord EB, Aziz NM (2012) Health information needs and health-related quality of life in a diverse population of long-term cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns 89(2):345–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.08.014

Rabin C, Simpson N, Morrow K, Pinto B (2011) Behavioral and psychosocial program needs of young adult cancer survivors. Qual Health Res 21(6):796–806. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310380060

Zebrack B (2009) Information and service needs for young adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 17(4):349–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0469-2

Boyes AW, Girgis A, D’Este C, Zucca AC (2012) Prevalence and correlates of cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 6 months after diagnosis: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer 12:150

Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, West MM (2005) Adult cancer survivors: how are they faring? Cancer 104(11 Suppl):2565–2576. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21488

Henry M, Habib LA, Morrison M, Yang JW, Li XJ, Lin S, Zeitouni A, Payne R, MacDonald C, Mlynarek A, Kost K, Black M, Hier M (2014) Head and neck cancer patients want us to support them psychologically in the posttreatment period: survey results. Palliat Support Care 12(6):481–493. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951513000771

Rabin C, Simpson N, Morrow K, Pinto B (2013) Intervention format and delivery preferences among young adult cancer survivors. Int J Behav Med 20:304–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9227-4

Cheung CK, Zebrack B (2017) What do adolescents and young adults want from cancer resources? Insights from a Delphi panel of AYA patients. Support Care Cancer 25(1):119–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3396-7

Hong Y, Dahlke DV, Ory M, Hochhalter A, Reynolds J, Purcell NP, Talwar D, Eugene N (2013) Designing iCanFit: a mobile-enabled web application to promote physical activity for older cancer survivors. JMIR Res Protoc 2(1):e12. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.2440

Craft LL, VanIterson EH, Helenowski IB, Rademaker AW, Courneya KS (2012) Exercise effects on depressive symptoms in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers 21(1):3–19

Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Snyder C, Geigle P, Gotay C (2014) Are exercise programs effective for improving health-related quality of life among cancer survivors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum 41(6):E326–E342. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.E326-E342

Piet J, Wurtzen H, Zachariae R (2012) The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on symptoms of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 80(6):1007–1020. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028329

Haller H, Winkler MM, Klose P, Dobos G, Kummel S, Cramer H (2017) Mindfulness-based interventions for women with breast cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol 56(12):1665–1676. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2017.1342862

Carmody JF, Olendzki BC, Merriam PA, Liu Q, Qiao Y, Ma Y (2012) A novel measure of dietary change in a prostate cancer dietary program incorporating mindfulness training. J Acad Nutr Diet 112(11):1822–1827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.008

James E, Freund M, Booth A, Duncan MJ, Johnson N, Short CE, Wolfenden L, Stacey FG, Kay-Lambkin F, Vandelanotte C (2016) Comparative efficacy of simultaneous versus sequential multiple health behavior change interventions among adults: a systematic review of randomised trials. Prev Med 89:211–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.012

Rock CL, Flatt SW, Byers TE, Colditz GA, Demark-Wahnefried W, Ganz PA, Wolin KY, Elias A, Krontiras H, Liu J, Naughton M, Pakiz B, Parker BA, Sedjo RL, Wyatt H (2015) Results of the exercise and nutrition to enhance recovery and good health for you (ENERGY) trial: a behavioral weight loss intervention in overweight or obese breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 33(28):3169–3176. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.61.1095

Leach CR, Diefenbach MA, Fleszar S, Alfano CM, Stephens RL, Riehman K, Hudson SV (2019) A user centered design approach to development of an online self-management program for cancer survivors: springboard beyond cancer. Psycho-oncology 28(10):2060–2067

Timmerman JG, Tönis TM, Dekker-van Weering MG, Stuiver MM, Wouters MW, van Harten WH, Hermens HJ, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM (2016) Co-creation of an ICT-supported cancer rehabilitation application for resected lung cancer survivors: design and evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res 16(1):1–11

Funding

This project was internally funded by Cancer Council SA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Approval was received from Cancer Council Victoria’s Human Research Ethics Committee (IER1904).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was provided by each participant.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was provided by each participant.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 20 kb).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grant, A.R., Koczwara, B., Morris, J.N. et al. What do cancer survivors and their health care providers want from a healthy living program? Results from the first round of a co-design project. Support Care Cancer 29, 4847–4858 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06019-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06019-w