Abstract

Purpose

The provision of spiritual care by an interprofessional healthcare team is an important, yet frequently neglected, component of patient-centered cancer care. The current study aimed to assess the relationship between individual and occupational factors of healthcare providers and their self-reported observations and behaviors regarding spiritual care in the oncologic encounter.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was administered to healthcare providers employed at a large Comprehensive Cancer Center. Pearson’s chi-square test and logistic regression were used to determine potential associations between provider factors and their observations and behaviors regarding spiritual care.

Results

Among the participants emailed, 420 followed the survey link, with 340 (80.8%) participants completing the survey. Most participants were female (82.1%) and Caucasian (82.6%) with a median age was 35 years (IQR: 31–48). Providers included nurses (64.7%), physicians (17.9%), and “other” providers (17.4%). There was a difference in provider observations about discussing patient issues around religion and spirituality (R&S). Specifically, nurses more frequently inquired about R&S (60.3%), while physicians were less likely (41.4%) (p = 0.028). Also, nurses more frequently referred to chaplaincy/clergy (71.8%), while physicians and other providers more often consulted psychology/psychiatry (62.7%, p < 0.001). Perceived barriers to not discussing R&S topics included potentially offending patients (56.5%) and time limitations (47.7%).

Conclusion

Removing extrinsic barriers and understanding intrinsic influences can improve the provision of spiritual care by healthcare providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The provision of spiritual care to patients coping with chronic or advanced illness, like cancer, has traditionally been an overlooked component of holistic, patient-centered care [1,2,3]. Despite an increase in attention to the role of religion and spirituality (R&S) in cancer care, evidence suggesting a positive impact on patient treatment preferences and care outcomes, as well as multiple national practice and ethical guidelines that include spiritual care as a vital component of high-quality patient-centered care (e.g., Institute of Medicine, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations), its uptake by healthcare providers has been limited [4,5,6]. Broadly, spiritual care can be defined as “interventions… that facilitate the ability to express the integration of the body, mind, and spirit to achieve wholeness, health, and a sense of connection to self, others, and or a higher power” [7]. Spiritual care is of particular importance to patients diagnosed with cancer as this diagnosis presents challenges to all dimensions of life: biological, psychological, social, and spiritual [8]. Additionally, patients often want R&S needs integrated into their cancer treatment, yet this need often goes unmet [3, 9]. Collectively, the lack of spiritual care provided to patients diagnosed with cancer by their healthcare team can be particularly detrimental to patient experience and associated health outcomes.

Many healthcare providers recognize R&S as an important topic for cancer patients, but that belief rarely translates to their clinical practice [10]. Spiritual care is not the responsibility of a singular type of provider, as all healthcare providers should be able to address different aspects of suffering and distress related to the patients’ illness experience [11]. To improve the frequency and quality of spiritual care, an interprofessional approach is essential [12]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network advocates that, while chaplains/pastoral care are important spiritual care specialists, all providers should be equipped to provide general spiritual care [12]. Research has focused on extrinsic barriers for the provision of spiritual care, including lack of education and training, understanding how to engage with patients around R&S issues without compromising the therapeutic relationship, and how spiritual care fits within the scope of practice for different providers [13, 14]. Less is known, however, about the intrinsic factors that influence provider observations and behaviors around their role in the provision of spiritual care [15]. Therefore, the current study aimed to assess the relationship between individual and occupational factors of healthcare providers and their self-reported observations and behaviors regarding spiritual care for cancer patients.

Methods

Participant population and study procedure

To be eligible for enrollment in the study, participants had to be a healthcare provider currently employed at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (OSUCCC)–Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute. The current study utilized a cross-sectional, single-instruction online survey design. For the purposes of the current study, healthcare provider was defined as someone who was authorized to diagnose and/or treat physical or mental health disorders (e.g., surgeon, medical oncologist, nurse, social worker, psychologists, etc.); all participants were over 18 years of age and able to read the English language. Chaplains/members of the Pastoral Care Department served as study consultants (e.g., reviewed survey language) and, thus, were excluded from participation.

An internal employee email listserv for the OSUCCC was obtained and potential participants were sent a study description and survey link via electronic mail. The survey was hosted within the Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCAP) platform, a secure web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies [16, 17]. The initial link sent participants to a 2-question screener to confirm their role as a healthcare provider and obtain study consent. Participants were not able to proceed with the survey if consent was not given. After completing the survey, participants received a $5.00 gift card incentive. The study protocol was approved by The Ohio State University institutional review board (#2019C0167).

Measures

The survey contained items to assess individual and occupational demographic factors of the respondent, as well as observations and behaviors regarding the provision of spiritual care to patients. Individual demographic variables were collected and collapsed into relevant categories including gender (male vs. female), race (White vs. non-White), education level (< advanced/professional degree vs. advanced/professional degrees), relationship status (partnered vs. not partnered), and R&S identity (religious vs. non-religious). For R&S identity, the “religious” category included participants who identified as “religious and spiritual” or “religious, but not spiritual”; participants in the “non-religious” category included individuals who self-identified as “spiritual, but not religious” and “neither religious nor spiritual.” Occupational demographic information including provider type (physician vs. nurse vs. other), as well as nurse category (i.e. registered nurses, licensed practicing nurses and nurse practitioners), was assessed. Non-physician or nurse providers (e.g., physical therapists, audiologists, occupational therapists, and social workers) were categorized as “other” providers for purposes of analyses. The length of time respondents had been in practice (< 10 years vs. ≥ 10 years) and the frequency in which providers saw patients (< half of the days in the week vs > half of the days in the week) were also ascertained.

Respondents’ self-reported observations and behaviors about their role in spiritual care were assessed using questions adapted from The Religion and Spirituality in Medicine: Physicians’ Perspectives study (RSMPP) [13]. The RSMPP was one of the first measures to assess provider perceptions of religion and spirituality impact within the healthcare context. Since its inception, the RSMPP has been translated to multiple languages and utilized in more than 30 publications [18, 19]. Provider observations assessed using questions from the RSMPP included a multi-selection question evaluating the perceived barriers to providing spiritual care (e.g., discomfort, no training, time limitations, etc.). Additionally, participants were asked an open-ended question regarding what members of the healthcare team should approach the patient about R&S needs. Free-text responses were coded for each provider type mentioned and recoded as a categorical variable. Then, the variable “explicitly lists their role” (yes vs. no) was created, if the participant explicitly listed a member of the healthcare team that matched their provider role. For example, if the participant was a physician and they listed roles like “medical oncologist,” “surgeon,” or “attending physician,” that was considered a match while a physician that listed roles like “nurse,” “advanced practice provider,” and “no one” would not be considered an explicit match. Behaviors assessed included inquiring about R&S issues with patients (yes vs. no), how much time was spent engaging in R&S with patients (the right amount/too much vs. too little), and referral behaviors. For referral behaviors, participants were given a short hypothetical scenario about an interaction with a man in grief over his wife who died 2 months prior. This vignette was designed to determine provider referral behaviors without giving the impression that the patient met DSM criteria for a mental health diagnosis [20]. Participants were then asked, “Which of the following providers would you prefer to refer to first?” Options included chaplain, clergy member, or psychiatrist/psychologist. Questions used to assess provider observations can be found in supplemental Table 1.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as frequency (relative frequency: %) and mean (standard deviation) for categorical and continuous data, respectively. If respondents skipped questions, they were excluded from the total respondent count in the calculation of percentages for a given response to a prompt. Responses to variables were collapsed into categorical variables, as needed. The number of barriers indicated by participants was summed and then dichotomized into categories for analysis (≤ 1 vs. > 1). Responses regarding provider referral behaviors were collapsed into chaplain/clergy versus psychiatrist/psychologist categories. Bivariate analysis examining associations between provider type observations and behaviors around spiritual care included chi-square test of independence. For significant bivariate associations, Cramer’s V (φc) was used to estimate the effect size, or strength, of the association. Cramer’s V (range: 0–1) values between 0.05 and 0.10 were considered a weak relationship, whereas values between 0.10 and 0.15 were considered a moderately strong relationship, and values > 0.15 were indicative of a strong relationship [21]. Logistic regression was used to assess the associations between provider individual and occupational factors and individual observations and behaviors around spiritual care. Statistical significance was assessed at α = 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS v27.

Results

A total of 2266 potential participants were emailed using an internal employee listserv. Among potential participants, 420 opened the email and followed the survey link (420/2266; 18.5% response rate). After downloading and reviewing the completed data, 74 individuals did not proceed past the consent form; six participants were dropped from analysis for not indicating provider type. The final analytic cohort was 340 participants (n = 340/420; 80.8% completion rate).

Participant demographics

The majority of participants self-identified as female (n = 261, 82.1%) and White (n = 281, 82.6%) and were in a relationship with a significant other or partner (n = 244, 77.5%). More than one-half of participants had an advanced or professional degree (n = 182, 57.1%); while many participants (n = 183, 57.5%) classified themselves as religious, 42.5% (n = 135) of participants identified as only spiritual or neither religious nor spiritual (i.e., “not religious”). Respondent healthcare provider roles included physician (n = 61; 17.9%), nurse (n = 220; 64.7%), and other (n = 59; 17.4%). Most respondents had been in practice < 10 years (n = 196, 57.6% vs. ≥ 10 years n = 144, 42.4%) and spent more than half their time per week seeing patients (n = 171, 50.3% vs. < half of the days per week n = 169, 49.7%) (Table 1).

Comparison of observations and behaviors regarding spiritual care by provider type

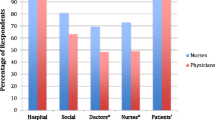

Differences were detected in self-reported provider spiritual care behaviors. Specific to spiritual care behaviors, nurses were more likely to report referring a grieving patient to chaplaincy/clergy (n = 135, 65.5%), whereas physicians and other providers more often reported consulting a psychologist or psychiatrist (n = 32, 62.7% and n = 28, 53.8%, respectively) (p < 0.001). More nurses and other providers explicitly self-reported seeing their role as someone who should approach the patient about R&S topics (n = 64, 64.0% and n = 26, 70.3%); in contrast, physicians more frequently did not report engaging with patients around R&S as within their role (n = 19, 65.5%) (p = 0.006). Similarly, nurses and other providers more often reported inquiring about patient R&S issues (n = 129, 60.3% and n = 20, 50.8%, respectively), whereas a greater proportion of physicians reported not inquiring about R&S (n = 34, 58.6%) (p = 0.03). The associations between provider types and spiritual care behaviors were strong (φc range: 0.15–0.29). In contrast, there were no differences among providers regarding the amount of time needed to engage with patients around R&S topics (p = 0.11) or the number of barriers to provide spiritual care (p = 0.54) (Table 2). Of note, approximately half (53.5%) of participants indicated at least one barrier to care with the most frequent barriers being “potentially offending patients” (56.5%) and “time limitations” (47.7%); 46.5% of respondents indicated multiple barriers to R&S discussions with patients. The frequency of provider self-reported barriers to providing spiritual care is noted in Fig. 1.

Associations between provider factors and observations around spiritual care

Both individual and occupational factors were associated with provider observations around their role in spiritual care (Table 3). Of note, provider type and religious identity were associated with participants’ belief that their specific role as a member of the healthcare team should involve interacting with patient about R&S topics. Specifically, respondents who identified as being religious were much more likely to believe their role as a healthcare provider included R&S versus non-religious respondents (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.09, 4.34, p = 0.03). Nurses and other non-physician providers also had higher odds to report that the provision of R&S support was part of their role as a member of the healthcare team (referent, physicians: OR 4.00, 95% CI 1.41, 11.26, p = 0.009 and OR 4.63, 95% CI 1.41, 15.15, p = 0.01, respectively). In contrast, respondent gender, race/ethnicity, and frequency of clinical encounters with patients were not associated with provider observations of their role in spiritual care (p-range: 0.11–0.98). In addition, self-reported religious identity and provider type were not associated with the number of perceived barriers to spiritual care (all p > 0.05). Healthcare providers in practice < 10 years did, however, report a greater number of barriers to discussing R&S topics compared with respondents who had been in practice > 10 years (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.14, 2.25, p = 0.01).

Associations between provider factors and behaviors around spiritual care

Both individual and demographic factors were associated with provider behaviors regarding spiritual care (Table 4). Providers who were religious were more likely to indicate feeling that they spent too little time engaging with patients around R&S topics (OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.40, 3.56, p = 0.001) and/or inquiring about patient R&S issues (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.20, 3.01, p = 0.006). While self-reported religious identity was not associated with referral preference (i.e., clergy vs. non-clergy) (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.40, 1.11, p = 0.12), provider type was associated with referral preferences, as well as likelihood to inquire about patient R&S issues. More specifically, nurses were less likely to refer a grieving patient to a psychologist or psychiatrist (OR 0.23, 95% CI: 0.11, 0.50, p < 0.001) and were more likely to inquire about patient R&S issues (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.05, 4.25, p = 0.04) compared with physicians. Provider type was not associated with the belief that too little time was spent engaging with patients around R&S topics (p-range: 0.11–0.92). Respondent gender, race, years in practice, and frequency of clinical encounters with patients were also not associated with behaviors regarding patient spiritual care (p-range: 0.07–0.98).

Discussion

R&S can positively influence cancer patient experience of care, as well as biological, psychological, social, and spiritual health outcomes [4, 22,23,24,25]. Patient experiences within the cancer care continuum vary and the complexity of R&S patient needs highlight the importance of an interprofessional approach to the provision of spiritual care [26,27,28]. The current study was important as it focused on intrinsic factors, including individual and occupational demographics, which influenced provider observations and behaviors around their role in spiritual care. Respondent behaviors regarding their role around spiritual care varied more by provider type compared to observations. Multivariate analysis also revealed that both individual and occupational factors, specifically provider type and religious identity, were associated with provider observations and behaviors around spiritual care.

Providers who identified as religious were more likely to explicitly believe their role as a member of the healthcare team included approaching patients about R&S, as well as indicate “too little time” to talk about R&S topics, and to inquire about R&S with patients. This finding is consistent with a review conducted by Best and colleagues (2016) that identified “insufficient time” and “personal discomfort” as the most frequently cited barriers to spiritual care [14]. The current study was consistent with previous data that had highlighted the associations between healthcare provider intrinsic religiosity (defined as the extent to which R&S is the main motivation behind one’s choices and behaviors) on interactions with patients around R&S [15, 29]. In aggregate, the results support previous research that highlights the importance of provider self-awareness of their own R&S beliefs and how those beliefs may influence interactions with their patients. To this point, several professional organizations have recommended that providers participate in spiritual care curriculum, which should include provider self-reflection and increased self-awareness of how personal belief systems may implicitly or explicitly impact the care provided to patients [12, 28, 30]. Additionally, providers who are more aware of their own R&S beliefs will be better able to assess and address the spiritual needs and concerns of their patients [31].

Provider type also influenced observations and behaviors relative to spiritual care. Specifically, compared with physicians, nurses and other providers were fourfold more likely to indicate that their role as a healthcare team member included providing patients with R&S support. Of note, nurses were less likely to report referring a grieving patient to a psychologist/psychiatrist and were more likely to utilize clergy/pastoral services compared with physician respondents. Nurses were also more likely to inquire about R&S issues than physicians. In fact, patients often describe receiving spiritual care more often from nurses than physicians [32, 33]. Up to three-quarters of patients have reported a wish, however, that physicians would be more willing to address their spiritual needs [34]. Due to variations in training, including models of care and scope of practice, some differences among providers and their approach to patients should be expected [35]. For example, physician training may emphasize a traditional medical model regarding the conceptualization and treatment of disease, whereas nurse training may emphasize a more holistic understanding of the patient (biological, psychological, social, and spiritual) [36]. In additional, physicians may face multiple barriers to provide spiritual care compared with nurses or other providers, including having less time with patients. Data from the current study suggest that nurses may be an important entry point to provide cancer patients with spiritual care and, thus, may facilitate greater awareness of spiritual care resources, including pastoral care, to the other members of the healthcare team and the patient. Our own research group has developed and is currently piloting a web-based resource that allows patients to place referrals to pastoral care directly instead of requesting a consult through a member of the healthcare team, as well as the ability to access R&S resources from an established library of materials.

The results of the current study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. For example, online survey methods may be subject to volunteer or self-report bias and may not completely align with provider behaviors in their daily clinical practice. Additionally, the study results may not be generalizable to other health systems in the United States as participants were recruited from a single-institution/large comprehensive cancer center in the Midwest. This is particularly important in the context of R&S in healthcare, as different hospital systems have varying types of support resources for patients (e.g., pastoral care departments) and R&S beliefs vary in prevalence within different regions of the United States and some hospital systems are religiously affiliated (e.g., Catholic hospitals) [37]. Also, the current sample was homogenous across a few demographic factors, which limited more nuanced comparative analysis. For instance, participants in the current study were a highly educated sample and mostly White, which could have influenced the results and limited the generalizability to other provider populations.

In conclusion, patient R&S beliefs and the availability of spiritual care are important components of patient-centered care, not only in the context of end-of-life or terminal illness, but across the treatment trajectory. Thus, increasing the provision of spiritual care from the interprofessional healthcare team by removing extrinsic barriers and understanding intrinsic influences is essential. The current study demonstrated that both individual and occupational factors influenced provider observations and behaviors around spiritual care, with religious identity and provider type being the most influential factors. Addressing extrinsic and intrinsic barriers, such as tailoring training for providers in spiritual care to specific roles on the healthcare team and increasing provider self-awareness of their own R&S beliefs, may improve the delivery of spiritual care, thereby improving patient-centered care for cancer patients.

References

Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, Phelps AC, Loggers ET, Wright AA, Block SD, Lewis EF, Peteet JR, Prigerson HG (2010) Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol 28:445–452. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005

Peteet JR, Balboni MJ (2013) Spirituality and religion in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 63:280–289. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21187

Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Amobi A, Phelps AC, Gorman DP, Zollfrank A, Peteet JR, Prigerson HG, VanderWeele TJ, Balboni TA (2013) Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. J Clin Oncol 31:461–467. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6443

Koenig HG (2012) Religion, spirituality, and health: the research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012:1–33. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/278730

Koenig HG (2009) Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: a review. Can J Psychiatr 54:283–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370905400502

Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA (2013) Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

American Nurses Association, Health Ministries Association (2017) Faith Community Nursing: scope and standards of practice, 3rd edn. American Nurses Association, Inc., Silver Spring

Weaver AJ, Flannelly KJ (2004) The role of religion/spirituality for cancer patients and their caregivers. South Med J 97:1210–1214. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146492.27650.1C

Palmer Kelly E, Paredes AZ, DiFilippo S, Hyer M, Myers B, McGee J, Rice D, Bae J, Tsilimigras DI, Pawlik TM (2020) Do religious/spiritual preferences and needs of cancer patients vary based on clinical- and treatment-level factors? Ann Surg Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-08607-2

Best M, Butow P, Olver I (2015) Do patients want doctors to talk about spirituality? A systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns 98:1320–1328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.04.017

Siler S, Mamier I, Winslow BW, Ferrell BR (2019) Interprofessional perspectives on providing spiritual care for patients with lung cancer in outpatient settings. Oncol Nurs Forum 46:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.ONF.49-58

Puchalski CM, Sbrana A, Ferrell B, Jafari N, King S, Balboni T, Miccinesi G, Vandenhoeck A, Silbermann M, Balducci L, Yong J, Antonuzzo A, Falcone A, Ripamonti CI (2019) Interprofessional spiritual care in oncology: a literature review. ESMO Open 4:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000465

Phelps AC, Lauderdale KE, Alcorn S, Dillinger J, Balboni MT, van Wert M, VanderWeele TJ, Balboni TA (2012) Addressing spirituality within the care of patients at the end of life: perspectives of patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses. J Clin Oncol 30:2538–2544. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3766

Best M, Butow P, Olver I (2016) Doctors discussing religion and spirituality: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med 30:327–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315600912

Koenig HG, Büssing A (2010) The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions 1:78–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel1010078

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42:377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Patridge EF, Bardyn TP (2018) Research electronic data capture (REDCap). J Med Libr Assoc 106:142. https://doi.org/10.5195/JMLA.2018.319

Hvidt N, Kappel Kørup A, Curlin F, Baumann K, Frick E, Søndergaard J, Nielsen J, dePont Christensen R, Lawrence R, Lucchetti G, Ramakrishnan P, Karimah A, Schulze A, Wermuth I, Schouten E, Hefti R, Lee E, AlYousefi N, Balslev van Randwijk C, Kuseyri C, Mukwayakala T, Wey M, Eglin M, Opsahl T, Büssing A (2016) The NERSH international collaboration on values, spirituality and religion in medicine: development of questionnaire, description of data pool, and overview of pool publications. Religions 7:107. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7080107

Curlin FA, Lantos JD, Roach CJ, Sellergren SA, Chin MH (2005) Religious characteristics of U.S. physicians: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 20:629–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0119.x

Curlin FA, Odell SV, Lawrence RE et al (2007) The relationship between psychiatry and religion among U.S. physicians. Psychiatr Serv 58:1193–1198. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1193

Akoglu H (2018) User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk J Emerg Med 18:91–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjem.2018.08.001

Capps D (1995) Religion and mental health: current findings. Int J Psychol Relig 5:137–140. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr0502_10

Park CL, Sherman AC, Jim HSL, Salsman JM (2015) Religion/spirituality and health in the context of cancer: cross-domain integration, unresolved issues, and future directions. Cancer 121:3789–3794. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29351

Sherman AC, Merluzzi TV, Pustejovsky JE, Park CL, George L, Fitchett G, Jim HSL, Munoz AR, Danhauer SC, Snyder MA, Salsman JM (2015) A meta-analytic review of religious or spiritual involvement and social health among cancer patients. Cancer 121:3779–3788. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29352

Salsman JM, Fitchett G, Merluzzi TV, Sherman AC, Park CL (2015) Religion, spirituality, and health outcomes in cancer: a case for a meta-analytic investigation. Cancer 121:3754–3759. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29349

Hall P, Weaver L, Fothergill-Bourbonnais F et al (2006) Interprofessional education in palliative care: a pilot project using popular literature. J Interprof Care 20:51–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820600555952

Puchalski CM (2012) Spirituality as an essential domain of palliative care: caring for the whole person. Prog Palliat Care 20:63–65. https://doi.org/10.1179/0969926012Z.00000000028

Puchalski CM (2013) Integrating spirituality into patient care: an essential element of person-centered care. Pol Arch Med Wewn 123:491–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2014.03.023

Palmer Kelly E, Hyer M, Payne N, Pawlik TM (2020) Does spiritual and religious orientation impact the clinical practice of healthcare providers? J Interprof Care 34:520–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1709426

Astrow AB, Puchalski CM, Sulmasy DP (2001) Religion, spirituality, and health care: social, ethical, and practical considerations. Am J Med 110:P283–P287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00708-7

Surbone A, Baider L (2010) The spiritual dimension of cancer care. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 73:228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.03.011

Merath K, Palmer Kelly E, Hyer JM, Mehta R, Agne JL, Deans K, Fischer BA, Pawlik TM (2019) Patient perceptions about the role of religion and spirituality during cancer care. J Relig Health 59:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00907-6

De Camargos MG, Paiva CE, Barroso EM et al (2015) Understanding the differences between oncology patients and oncology health professionals concerning spirituality/religiosity: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 94:e2145. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002145

King DE, Bushwick B (1994) Beliefs and attitudes of hospital inpatients about faith healing and prayer. J Fam Pract 39:349–352

Cohen-Mansfield J, Jensen B, Resnick B, Norris M (2012) Assessment and treatment of behavior problems in dementia in nursing home residents: a comparison of the approaches of physicians, psychologists, and nurse practitioners. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 27:135–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2699

Sulmasy DP (2002) A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist 42(Spec No 3):24–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.24

Mansfield CJ, Mitchell J, King DE (2002) The doctor as God’s mechanic? Beliefs in the Southeastern United States. Soc Sci Med 54:399–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00038-7

Data and code availability

The data and software code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center-Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Elizabeth Palmer Kelly, Madison Hyer, and Tim Pawlik. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Elizabeth Palmer Kelly, Madison Hyer, Diamantis Tsilimigras, and Tim Pawlik and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of The Ohio State University (#2019C0167).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Participants signed an informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 14 kb).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palmer Kelly, E., Hyer, M., Tsilimigras, D. et al. Healthcare provider self-reported observations and behaviors regarding their role in the spiritual care of cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 29, 4405–4412 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05957-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05957-1