Abstract

Background

Nutritional impairment is common in cancer patients and adversely affects quality of life (QoL). The aim of this study was to investigate the association between nutritional status and QoL in incurable cancer patients in palliative care.

Methods

A prospective cohort with incurable cancer patients referred to the specialized Palliative Care Unit of the National Cancer Institute in Brazil was conducted. The nutritional risk (NR) was assessed using the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment short form (PG-SGA SF), and cancer cachexia (CC) was defined according to the international consensus. QoL was evaluated using the Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative (QLQ-C15-PAL). Multivariate linear regressions analyses were performed to assess the relationship between the nutritional status and QoL scores.

Results

A total of 1039 consecutive patients were included. A high prevalence of NR (85.4%) and CC (78.7%) were observed. The patients with worse nutritional status presented significantly poorer physical, emotional, symptoms domains scales, and overall QoL. CC were significantly associated with QoL scores for dyspnea (p = 0.013), insomnia (p = 0.046), and appetite loss (p = 0.015), while NR were associated with all the QoL domains scales covered in QLQ-C15-PAL.

Conclusion

Our findings support that impaired nutritional status was associated with poor QoL in incurable cancer patients. NR assessed by PG-SGA SF better reflects physical, emotional, symptom burden, and overall QoL scores. Thus, this tool may contribute in identifying patients at risk of deterioration QoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, and in developing countries, the majority of tumors are diagnosed at an incurable stage [1]. Patients with incurable disease often experience multiple symptoms and functional deficits. The most important goals in palliative care are symptom control and the improvement or maintenance of the quality of life (QoL) of patients as well as their caregivers, who will also be distressed by the incurable nature of the disease [2]. QoL is a subjective and multidimensional concept that involves functionality, emotional, and cognitive and social functions relating to personal perceptions of health status and the presence of symptoms [3].

The prevalence of nutritional impairment increases as the disease progresses. Malnutrition in palliative care patients is common and diverges according to assessment method, tumor site, and clinical setting [4,5,6,7]. In a previous study, we showed that up to 83% of palliative cancer patients were malnourished [8]. Poor nutritional status is associated with negative predictors of outcome in cancer patients including QoL [9,10,11]. Therefore, nutritional assessment is recommended at all stages of the disease, from diagnosis to end-of-life, making nutrition management a significant component of multimodal cancer care [12].

Suitable nutritional interventions can improve the well-being and QoL of this population [13, 14]. Patients with incurable cancer present additional challenges when it comes to supplying patient-centered care. Since nutritional status is potentially modifiable factors known to have a negative impact on prognosis, it is an urgent need to encourage the incorporation of nutritional care into the agenda of oncology health professionals’ teams [15].

The relationship between nutritional status and reduced QoL has also been reported in other studies [16,17,18,19], but these have involved patients at different stages of the disease and not necessarily in palliative care. In addition, despite the high prevalence of poor nutritional status in incurable cancer patients, there is still a paucity of data in the literature regarding its impact on QoL, particularly in South America.

This study therefore sought to establish the prevalence of nutritional burden determined by two key diagnostic measurements of nutritional status used in clinical practice and to investigate the influence of nutritional status on the QoL of patients in palliative care at a reference cancer care center in Brazil.

Methods

Study population

The INCA Ethics Committee (registration number 1.407.458 of 2016) approved this protocol, and all the patients signed informed consent form before participating in the study. The data were collected prospectively at the specialist palliative care unit (PCU) of José Alencar Gomes da Silva National Cancer Institute (INCA) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between June 2016 until June 2018. This PCU is a 56-bed exclusive palliative care in comprehensive oncology center that comprise a tertiary institute for cancer prevention, control, and treatment in Brazil. All newly consecutive referred patients were evaluated during their first visit to the PCU and inpatients within 48 h of hospital admission.

The trained researchers recorded the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score ranges from 0 (death) to 100% (full function), wherein a higher score indicated a better ability to carry out normal daily activities, self-care, and work [20]. The eligible criteria were incurable cancer (defined as not curable but might receive antineoplastic treatment aimed at alleviate symptoms) of any tumor site, both genders, age ≥ 20 years, and KPS score ≥ 30%. The following data were collected from the electronic medical records: primary cancer site, extent of metastatic disease (if present), previous antitumor treatment, and comorbidities. Furthermore, socio-demographic data (age, gender, and ethnicity), anthropometry, nutritional risk (NR), and QoL were obtained by researchers with patients and recorded in a study-specific questionnaire. A routine laboratory analysis was performed on the day of enrollment at the PCU.

Anthropometry

Measurements of weight (kilograms; kg) and height (meters; m) were obtained with the patients wearing light clothing and no shoes. A calibrated portable digital scale (Wiso®, model 905, Brazil) with an accuracy of 0.1 kg and 180 kg capacity was used to weigh the patients. For those patients who were unable to stand, an in-bed scale system was used [Stryker®, Go Bed II; Stryker Medical, United States of America (USA)]. Height was measured within 0.5 cm using a tape stadiometer on the wall. When this was not possible, height was estimated using knee height, which was measured with the knee and ankle joints flexed at 90°, using an anthropometer and calculated according to the formulas reported by Chumlea et al. [21]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared. A low BMI was considered a value < 20 kg/m2 [22].

The skinfold thickness of triceps (TSF, mm) was measured using a skinfold caliper Lange® (Cambridge Scientific Industries, USA). We also assessed arm circumference (AC, cm) and mid-arm circumference (MAC) at the same point of TSF. The mid-upper arm muscle area (MUAMA, cm2) was calculated used the equation proposed by Heymsfield et al. [23]. Low muscle mass was characterized when MUAMA < 32 cm2 for males and < 18 cm2 for females [22].

Nutritional risk

NR was evaluated using the Portuguese version of the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment short form (PG-SGA SF©), available at Pt.Goblal.org, after acquiring permission (©FD Oterry). This tool consists of four boxes in the first part of the PG-SGA, which was self-reported by the patients. Box 1 focuses on weight history (maximum score of 5), box 2 on food intake (maximum score of 4), box 3 on symptoms of nutritional impact (maximum score of 24), and box 4 on functional status (maximum score of 3). The higher the overall score, the worse the nutritional status. Those patients with a PG-SGA SF score of ≥ 9 were classified as being at NR [24].

Cancer cachexia

Patients were classified as cachectic according to the international consensus [22]. One of three criteria had to be met: weight loss (WL) ≥ 5% in the past 6 months, or BMI < 20 kg/m2, and WL ≥ 2% in the past 6 months, or low muscle mass and WL ≥ 2% in the past 6 months.

Quality of life

QoL was assessed using the Portuguese version of the Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative (QLQ-C15-PAL) [25, 26]. This tool consists of 15 questions: two multi-item functional scales (physical and emotional functioning), two multi-item symptom scales (fatigue and pain), plus five single-item symptom scales (nausea/vomiting, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation), and one final question referring to overall QoL. Patients self-reported rated each question/item on a numerical scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much), with the exception of global QoL which was rated from 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent). Each scale was transformed into a score ranging from 0 to 100, according to the respective scoring manual [27]. We considered QLQ-C15-PAL domain scores as continuous variables. The higher the score for the symptom scales, the higher the level of symptomatology, and therefore the lower the QoL. However, conversely, the higher the score for the functional scale and global health status, the higher the level of health and QoL.

Statistical analysis

A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed to assess distribution symmetry. Descriptive statistics (count/frequency [%], means/± standard deviation, or median/interquartile ranges, as appropriate) were used to describe patient characteristics. Differences in QoL scores by clinical and nutritional variables were evaluated using independent t test.

In order to test independent relationships between nutritional status (independent variables) and QLQ-C15-PAL domain scores (dependent variables), several multivariate linear regression models were performed, controlling for gender (female vs. male), age (years), KPS (%), type of tumor (diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancers vs. others), and current location of care (inpatient vs. outpatient). It was created 10 multivariate regression models one for each dependent variable analyzed (physical functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, and overall QoL). Statistical analysis was performed using Stata® version 12.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 1039 consecutive patients (74.6% outpatients) were included in the study. The mean age was 61.7 (± 13.5) years and the majority of the patients were female. The most common type of cancer was that of the gastrointestinal tract, followed by gynecological cancer. The majority of the patients had metastatic disease and received radiotherapy as previous treatment. The median KPS was 50% (Table 1).

Although the mean of BMI is considered proper/suitable, a high mean of WL was verified (13.3%). According to MUAMA, a low average was found in male, but not in female. In addition, low serum albumin and elevated CRP level were verified (Table 1). A total of 79 (9.92%) patients had a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, of which, concomitantly, 52 were cachectic and 56 presented NR (data not shown).

A high prevalence of NR (85.4%) and CC (78.7%) was observed. There was no statistically significant difference in mean overall QoL scores for age and gender, but patients with poor performance status had significantly lower overall QoL. Nutritional impairment was significantly associated with reduced QoL according QLQ-C15-PAL domain scales (physical, emotional, symptoms, and overall QoL). Worst averages of overall QoL domains covered in QLQ-C15-PAL reflect NR (p < 0.001) and CC (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

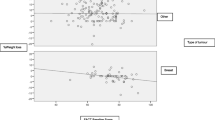

Approximately 40% of the patients considered non-cachectic reported a good overall QoL (score ≥ 6), in contrast with 20% of the CC patients (p < 0.001). In relation to the classification of nutritional risk, approximately 60% of the patients not at NR considered their overall QoL to be good (score ≥ 6), compared to approximately 20% of those at NR (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Patient response to QLQ-C15-PAL question 15 (1 to 7) according to the classification of (a) nutritional risk and (b) cancer cachexia in advanced cancer patients. QoL, quality of life; PG-SGA SF, Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment short form. The difference of the mean score of question 15 was statistically significant (P < 0.001) between a subjects not at nutritional risk [5.3 (± 1.6)] and subjects at nutritional risk [4.1 (± 1.8)] and b non-cachectic [4.8 (± 1.7)] and cachectic [4.1 (± 1.8)] subjects

Multiple linear regression analysis demonstrates that all the domains related to QoL were associated with NR determined by PG-SGA SF (Table 3). However, only dyspnea (p = 0.013), insomnia (p = 0.046), and appetite loss (p = 0.015) showed a statistically significant association with CC (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study reports on unprecedented data from a large sample of incurable cancer patients in palliative care followed at a national reference cancer care center in Brazil [28]. Our results showed that NR as well as CC were significantly related to a worse QoL. Additionally, provides data on the nutritional profile of this population that previously scarce in the country. To our knowledge, this is the first study that investigates the relationship of nutritional impairment determined by two different diagnostic measures with QoL specific in incurable cancer patients. In addition, our results demonstrated that the NR assessed by PG-SGA SF significantly correlated to overall QoL score, physical, emotional, and symptom scales, while CC significantly correlated to some symptom scales.

The relationship between nutrition impaired and QoL in advanced cancer patients have been reported by other previous studies [4, 10, 18, 29, 30]. However, studies with the same scope in incurable cancer patients are limited. Shahmoradi et al. [18] investigated the association between NR and QoL in cancer patients receiving hospice home care with the Hospice Quality of Life Index (HQLI) questionnaire and found that those with poorer nutritional status exhibited a lower QoL. According to these authors, PG-SGA scores significantly correlated with overall QoL scores, as well as psychophysiological, functional, and social/spiritual well-being [18]. Likewise, in a study conducted with advanced colorectal cancer patients, the QoL score evaluated by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) was worse among the cachectic and/or malnourished patients when different criteria for nutritional evaluation were used [29]. Daly et al. [30] assessed the relationship between nutritional status evaluated by the BMI adjusted WL grading system (WLGS) and QoL (EORTC QLQ-C30) in patients with advanced cancer. In line with our findings, the author reported that nutritional impaired assessed by WLGS was useful in identifying patients at risk of poor QoL [30].

According to our results, in general, younger patients reported worse QoL. About gender, physical and emotional functional were worse in male, while symptom scales were worse in female. Previous reports by Daly et al. [30] show inconsistent results. These authors categorized their sample as < 65, 66–73, and > 74 year and did not find difference in overall QoL score between these groups. In addition, these authors reported a poorer overall QoL score in women [30].

Notably, a high prevalence of nutritional disorders was verified in our sample. In study by Wallengren et al. [4], it was demonstrated that the prevalence of CC in palliative patients varies (12% to 85%) according to the definition used for its diagnosis [27]. Kwang and Kandiah [5] and Cunha et al. [8] reported the prevalence of NR evaluated by PG-SGA at 70.7% and 83.6%, respectively, in patients receiving palliative care, which is consistent with our findings. The mode by which nutritional status influence on QoL seems to be related to the complex interplay between inflammation and metabolic disorders related to malnutrition, which often leads to physical, biochemical deterioration and disease symptom burden beside that to other multidimensional factors associated with declining nutritional status such as the psychological, and social which affects QoL [17, 31, 32].

Of note, PG-SGA SF seems to be a more sensitive nutritional assessment method than the CC criteria for detecting changes in QoL domains. This was evidenced in this study, since NR determined by PG-SGA SF was associated with all the domains concerning of QLQ-C15-PAL, while the only associations with CC were found with the score symptoms of dyspnea, insomnia, and appetite loss. A possible explanation for this is that PG-SGA SF involves WL, the patient’s dietary intake, symptoms, and functional capacities, resulting in a multidimensional assessment, unlike the diagnosis of CC, which is centered on their consequences (e.g., WL, skeletal muscle depletion) rather than their causes [33,34,35]. Box 2 of the PG-SGA reflecting the presence of anorexia that is known to contributes to WL [36, 37]. Box 4 assesses the subjective report of performance status. Reduced physical performance is associated with poorer nutritional and functional outcomes, decreased QoL and survival [37]. Furthermore, the domain referring to symptom evaluation (Box 3) can increase the total score significantly, and this domain is one of the most common factors that can affect multiple QoL domains. Thus, our hypothesis is that PG-SGA’s multidimensional feature makes it a more sensitive tool to detect changes in QoL.

All aforementioned studies [4, 10, 18, 29, 30] with advance cancer demonstrate significative impact of nutritional status on cancer patients’ QoL. A systematic review including a total of 67 studies cancer patients reported a negative association between WL and QoL regardless of the tumor site [17]. Information about period of WL, the stage of CC and changes in QoL was not available in most included studies, but an inverse relationship between QoL and WL was found in 23 of the 27 studies which directly examined this [17]. Another recent systematic review examining nutrition support interventions in patients with incurable cancer [38]. Ten studies included examined QoL, with six studies reporting improvements following intervention. The most common nutritional interventions examined were nutrition counseling and dietary supplementation. These findings underline the importance of considering nutritional status when attempting to improve QoL.

Various issues may be associated with poorer patient’s QoL, and identification of those most related to QoL would permit health care professionals to management strategies most helpful to the patient. Management strategies may thus be optimized if the most significant predictors of QOL are considered in the course of palliative patient care [4, 30, 38].

In our study, malnutrition prevalence was explored in a consecutive cohort of patients with cancer at the palliative care unit of a reference tertiary care center. Validate instruments were used to assess nutritional status and QoL. However, it is important to note that the currently available QoL instruments does not address the issues which are most relevant for patients with malnutrition or CC, so the really impact of nutritional status on patients’ QoL cannot be completely explored. This study has some limitations: it was conducted at just one center and has a cross-sectional design, making it impossible to assess temporal variations in the variables under study. In addition, only a quarter of the sample consisted of inpatients, so that our findings apply better to outpatients, i.e., patients with better performance status.

In conclusion, the present study shows that poor QoL was associated with impaired nutritional status in a large sample of incurable cancer population in palliative care in Brazil. NR assessed by PG-SGA SF better reflects physical, emotional, symptom burden, and overall QoL scores and can contribute in identifying patients at risk of deterioration QoL. It is imperative that nutritional assessments be carried out on cancer patients in palliative care throughout the clinical process to plan targeted interventions with a focus on improving QoL.

References

WHO. World Health Organization (2002) National cancer control programmes: policies and managerial guidelines. 2nd ed. Geneva

Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, Friederich H-C, Villalobos M, Thomas M, Hartmann M (2017) Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD011129. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011129.pub2

WHO. World Health Organization. available in: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqolqualityoflife/en/. Accessed 10 Jan 2020

Wallengren O, Lundholm K, Bosaeus I (2013) Diagnostic criteria of cancer cachexia: relation to quality of life, exercise capacity and survival in unselected palliative care patients. Support Care Cancer 21:1569–1577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1697-z

Kwang AY, Kandiah M (2010) Objective and subjective nutritional assessment of patients with cancer in palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 27:117–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909109353900

Aktas A, Walsh D, Galang M, O'Donoghue N, Rybicki L, Hullihen B, Schleckman E (2017) Underrecognition of malnutrition in advanced cancer: the role of the dietitian and clinical practice variations. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 34(6):547–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909116639969

Thoresen L, Frykholm G, Lydersen S, Ulveland H, Baracos V, Prado CM, Birdsell L, Falkmer U (2013) Nutritional status, cachexia and survival in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma. Different assessment criteria for nutritional status provide unequal results. Clin Nutr 32(1):65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2012.05.009

Cunha MS, Wiegert EVM, Calixto-Lima L, Oliveira LC (2018) Relationship of nutritional status and inflammation with survival in patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. Nutrition 51–52:98–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2017.12.004

Ryan AM, Power DG, Daly L, Bhuachalla ĒN, Prado CM (2016) Cancer-associated malnutrition, cachexia and sarcopenia: the skeleton in the hospital closet 40 years later. Proc Nutr Soc 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002966511500419X

Kasvis P, Vigano M, Vigano A (2019) Health-related quality of life across cancer cachexia stages. Ann Palliat Med 8:33–42. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2018.08.04

Lis CG, Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Markman M, Vashi PG (2012) Role of nutritional status in predicting quality of life outcomes in cancer--a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J 11:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-11-27

Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Fearon K, Hütterer E, Isenring E, Kaasa S, Krznaric Z, Laird B, Larsson M, Laviano A, Mühlebach S, Muscaritoli M, Oldervoll L, Ravasco P, Solheim T, Strasser F, de van der Schueren M, Preiser JC (2017) ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr 36:11–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.07.015

Gagnon B, Murphy J, Eades M, Lemoignan J, Jelowicki M, Carney S, Amdouni S, di Dio P, Chasen M, Macdonald N (2013) A prospective evaluation of an interdisciplinary nutrition-rehabilitation program for patients with advanced cancer. Curr Oncol 20:310–318. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.20.1612

Baldwin C, Spiro A, Ahern R, Emery PW (2012) Oral nutritional interventions in malnourished patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 104:371–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djr556

Laviano A, Di Lazzaro L, Koverech A (2018) Nutrition support and clinical outcome in advanced cancer patients. Proc Nutr Soc 77:388–393. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665118000459

Polański J, Jankowska-Polańska B, Uchmanowicz I, Chabowski M, Janczak D, Mazur G, Rosińczuk J (2017) Malnutrition and quality of life in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 1021:15–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/5584_2017_23

Wheelwright S, Darlington AS, Hopkinson JB, Fitzsimmons D, White A, Johnson CD (2013) A systematic review of health-related quality of life instruments in patients with cancer cachexia. Support Care Cancer 21:2625–2636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1881-9

Shahmoradi N, Kandiah M, Peng LS (2009) Impact of nutritional status on the quality of life of advanced cancer patients in hospice home care. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 10:1003–1009

Zhang YH, Xie FY, Chen YW, Wang HX, Tian WX, Sun WG, Wu J (2018) Evaluating the nutritional status of oncology patients and its association with quality of life. Biomed Environ Sci 31:637–644. https://doi.org/10.3967/bes2018.088

Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA (1984) Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncol 2(3):187–193. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187

Chumlea WC, Guo SS, Steinbaugh ML (1994) Prediction of stature from knee height for black and white adults and children with application to mobility-impaired or handicapped persons. J Am Diet Assoc 94:1385–1388, 1391; quiz 1389-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-8223(94)92540-2

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, Jatoi A, Loprinzi C, MacDonald N, Mantovani G, Davis M, Muscaritoli M, Ottery F, Radbruch L, Ravasco P, Walsh D, Wilcock A, Kaasa S, Baracos VE (2011) Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 12:489–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7

Heymsfield SB, McManus C, Smith J, Stevens V, Nixon DW (1982) Anthropometric measurement of muscle mass: revised equations for calculating bone-free arm muscle area. Am J Clin Nutr 36:680–690. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/36.4.680

Ottery FD (1996) Definition of standardized nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition 12(1 Suppl):S15–S19. https://doi.org/10.1016/0899-9007(96)90011-8

Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, Arraras JI, Blazeby JM, Bottomley A, Fayers PM, de Graeff A, Hammerlid E, Kaasa S, Sprangers MA, Bjorner JB, EORTC Quality of Life Group (2006) The development of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: a shortened questionnaire for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur J Cancer 42:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.022

Nunes NA (2014) The quality of life of Brazilian patients in palliative care: validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 PAL (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL). Support Care Cancer 22:1595–1600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2119-1

Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K et al (2001) The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, 3rd editor, Brussels

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde (2017) Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva INCA. Estimativa 2018: Incidência de câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro. Available from: http://www1.inca.gov.br/estimativa/2018/estimativa-2018.pdf

Thoresen L, Frykholm G, Lydersen S, Ulveland H, Baracos V, Birdsell L, Falkmer U (2012) The association of nutritional assessment criteria with health-related quality of life in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Care 21(4):505–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01327.x

Daly L, Dolan R, Power D et al (2019) The relationship between the BMI-adjusted weight loss grading system and quality of life in patients with incurable cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12499

Capuano G, Gentile PC, Bianciardi F, Tosti M, Palladino A, Di Palma M (2010) Prevalence and influence of malnutrition on quality of life and performance status in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer before treatment. Support Care Cancer 18:433–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0681-8

Zhou T, Yang K, Thapa S, Liu H, Wang B, Yu S (2017) Differences in symptom burden among cancer patients with different stages of cachexia. J Pain Symptom Manag 53:919–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.325

Sadeghi M, Keshavarz-Fathi M, Baracos V, Arends J, Mahmoudi M, Rezaei N (2018) Cancer cachexia: diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 127:91–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.05.006

Isenring E, Bauer J, Capra S (2003) The scored Patient-generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) and its association with quality of life in ambulatory patients receiving radiotherapy. Eur J Clin Nutr 57:305–309. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601552

Araújo CS, de Oliveira RCB, Queiroz AR, Lanes RCR (2015) Patient-generated subjective global assessment and classic anthropometry: comparison between the methods in detection of malnutrition among elderly with cancer. Nutr Hosp 31:384–392. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2015.31.1.7543

Molfino A, Laviano A, Rossi Fanelli F (2010) Contribution of anorexia to tissue wasting in cachexia. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 4(4):249–253. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0b013e32833e4aa5

Vigano AAL, Morais JA, Ciutto L, Rosenthall L, di Tomasso J, Khan S, Olders H, Borod M, Kilgour RD (2017) Use of routinely available clinical, nutritional, and functional criteria to classify cachexia in advanced cancer patients. Clin Nutr 36:1378–1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.09.008

Blackwood HA, Hall CC, Balstad TR, Solheim TS, Fallon M, Haraldsdottir E, Laird BJS (2019) A systematic review examining nutrition support interventions in patients with incurable cancer. Support Care Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04999-4

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira, L.C., Abreu, G.T., Lima, L.C. et al. Quality of life and its relation with nutritional status in patients with incurable cancer in palliative care. Support Care Cancer 28, 4971–4978 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05339-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05339-7