Abstract

Purpose

Following a series of articles reviewing the basics of cancer pain management, in this article, we develop the guiding principle of our philosophy: the concept of multimorphic pain and how to integrate it as the innovative cornerstone of supportive care in cancer.

Method

Critical reflection based on literature analysis and clinical practice.

Results

This model aims to break with standard approaches, offering a more dynamic and exhaustive vision of cancer pain as a singular clinical entity, taking into account its multimorphic characteristics (cancer pain experience can and will change during cancer: aetiology, physiopathology, clinical presentation and consequences of pain) and the disruptive elements that can occur to influence its evolution (cancer evolution, concomitant treatments, pain from associated diseases, comorbidities and complications, or modifications in the environment). Our model establishes the main key stages for interdisciplinary management of cancer pain:

-

Early, personalised management that is targeted and multimodal;

-

Identification, including in advance, of potential disruptive elements throughout the care pathway, using an exhaustive approach to all the factors influencing pain, leading to patient and caregiver education;

-

Optimal analgesic balance throughout the care pathway;

-

Integration of this concept into a systemic early supportive care model from the cancer diagnosis.

Conclusions

Given the difficulties still present in the management of pain in cancer, and whilst cancer is often considered as a chronic condition, the concept of multimorphic pain proposes a practical, optimised and innovative approach for clinicians and, ultimately, for patients experiencing pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

We now have at our disposal a core of high-performance tools for managing cancer pain: a better understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms, interdisciplinary assessment, medical and non-medical treatments and access to innovative interventional techniques. Scientific studies nevertheless show that cancer pain still remains underestimated, poorly assessed and undertreated, particularly in the most severe cases [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Nowadays, cancer patients are mainly confronted with several poly-mechanisms of pain including neuropathic mechanisms [10, 11], as described in Table 1. Most cancer patients with pain are not referred to as a team of pain specialists [3]. Through a series of original articles, we propose a comparison between our experience in the field and the exhaustive data in the literature, on a variety of themes around cancer pain (assessments, use of opioids, pain emergencies, management of refractory pain, complementary integrative approaches) and with one guiding principle: the concept of multimorphic pain and its impact on patient management.

This conclusive article, whilst making no pretence of guaranteeing an answer to the question ‘how can management of cancer pain be improved?’, nevertheless aims to propose what could be the fundamental aspects of a new and pertinent management model. This model has two complementary aspects: consideration of cancer pain as an entity in its own right through the concept of multimorphic pain and an approach that is innovative and sustainable at a much broader scale in the organisation of supportive care, and beyond, of our healthcare systems.

Multimorphic cancer pain: an innovative concept for optimising management (Table 2)

Analysing the literature on cancer pain confronted with our experience as clinicians on an everyday basis has led us to considerably reconsider our approach and propose an innovative model that breaks with more traditional approaches.

From an etymological point of view, the term multimorphic refers to the possibility of adopting several forms at the same time and of changing form. This term seems to us to be adapted to the dynamic definition that we have sought to give to cancer pain: this type of pain can effectively evolve in how it presents, in relation to the different factors, whether or not they are linked to cancer and its management. The criteria that allow us to define the multimorphic nature of cancer pain are summarised in Table 2.

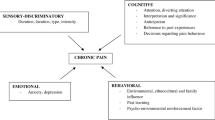

In short, cancer pain is not a fixed entity in itself or over time. It changes, alters, evolves or devolves, presenting in different forms at any time, from the diagnosis until after the cure or in palliative situations when applicable. These modifications depend on a series of intrinsic or extrinsic factors generally associated with each other, which play a part in initiating an imbalance at the level of pain management and thus create disruptions (Fig. 1). Today, many forms of cancer are seen as chronic conditions with varying degrees of improvement depending on type [12,13,14], considering cancer pain as multimorphic and managing it on the principle of the basics by preventing, identifying and treating these disruptions is a pertinent response to its complexity and the sustainability of the medical condition of these patients. Optimising state of health and management of risk factors or comorbidities, promoting compliance and therapeutic education, for example are all factors that improve cancer pain management in particular, although not exclusively [15, 16].

In order to complete this descriptive model, we propose a model-based approach of the exhaustive and comprehensive multimorphic cancer pain strategy, regardless of the stage of cancer, in four key points (Fig. 2), and which summarise our series of articles.

-

1.

The first is to have the objective of an optimal analgesic balance throughout the care pathway. This objective—however logical it might seem—must be formalised and above all adapted constantly to the multimorphic nature of the pain. It appears essential to us that constant attention to detail is preserved in the management of pain and that its trivialisation be avoided throughout the cancer care pathway. This objective will differ from one patient to another because of all the factors that influence pain, as well as those that are potentially variable over time, essentially in relation to the cure or progression of cancer and/or new intercurrent pathologies. These objectives must clearly be reasonable [17], but more than that, they must be adjusted to each clinical history, as well as being ambitious, for example with regard to early access to interventional techniques given their major impact on the quality of life and survival [15, 18,19,20,21,22,23].

-

2.

In order to implement this analgesic balance objective, management takes several forms through a number of fundamental points:

-

Implementation of synergy between disciplines: traditionally, pain medicine is associated with concepts that evolve. From an initially multidisciplinary philosophy (first level: consists in developing a plurality of disciplines that each play a part in understanding the object), many authors suggest switching to interdisciplinarity (second level: situation in which the different disciplines work together and in which there are exchanges of methods and results between them), or even transdisciplinarity (third level: openness to whatever is beyond and between the disciplines, with regard to a given subject and through a concept of plurality of levels of reality) [24,25,26]. Regardless, these concepts convey the fact of bringing, through the complementarity of opinions and skills—without neglecting any discipline in particular and promoting each one—a synergy of reflection and action on behalf of the patient and optimising his state of health. At our level, we retain the concept of interdisciplinarity as the cornerstone of our approach in the field of medicine in the broadest sense of the term (Fig. 3); nevertheless, we should move increasingly towards transdisciplinarity.

-

Early management: be it in curative or palliative situations, this is a key factor in the identification and success of an analgesic project, as shown clearly in clinical trials [18, 27,28,29,30,31,32].

-

A targeted approach to management: constant attention to detail, be it in terms of diagnosis or treatments, will make it possible to adjust our approach to the different issues with precision [15, 16].

-

Personalised management: as highlighted clearly in the table defining the multimorphic criteria of cancer pain (Table 2), each clinical history is the comparison of the different elements at a given moment, and will thus require a specific, differentiated approach from one patient to another.

-

A multimodal approach to treatment strategies: drug-based treatments for pain act on specific, and different, pathophysiological mechanisms. It is through this approach that some authors have even proposed an original classification of drug-based treatments [27], starting with the principle that a multimodal approach would take advantage of the synergy of the efficacy of these compounds, through the complementarity of the mechanisms of action. By extension, we believe that this multimodal philosophy should not be limited solely to drug-based treatments. Rather than a step-based approach, new interdisciplinary evaluations must lead to a multimodal response, also associating interventional techniques [15, 19,20,21,22, 33] and non-drug-based complementary approaches [15, 16, 33,34,35,36,37]. This multimodal scheme (Fig. 1) is in itself the best way of offering patients the solutions best adapted and relevant to their pain.

-

3.

The third cornerstone is the identification of potential disruptive elements, including in advance, throughout the care pathway by means of an exhaustive approach to all the factors that have an influence on pain. This third stage is the ‘core of the reactor’ in the model-based programme for managing multimorphic cancer pain that we propose: identifying and, when possible, correcting or modulating the disruptive factors of pain (Table 2).

-

4.

Certain authors have developed a model-based type of approach to the cancer care pathway in palliative situations which can absolutely be transposed into the management of cancer pain: the search for comfort and safety through a realistic and anticipated attitude throughout the care pathway is one of the factors in the success of a healthcare project [38, 39]. Our approach highlights the need to identify disruptive elements which could potentially provoke, intensify or modify cancer pain and thus break with the objective for balance throughout the care pathway. It is a potentially fragile balance that characterises control of cancer pain: destabilisation or lack of control of one or more factors of potential disruption (Table 2) and that can result in insufficient analgesia and its harmful effects in terms of quality of life [40] or comorbidities, such as depression [41]. This in turn leads to considering cancer and its consequences as elements of a whole—a chronic condition—from which they cannot be dissociated.

-

5.

Finally, the fourth stage in our model is considering the strategy described above as being integrated into a broader concept of early supportive care implemented as soon as the cancer diagnosis has been made.

-

6.

It is this more systemic approach that we will focus on in the second part of this article, as an extrinsic means of improving cancer pain management within the public health system (Figs. 2 and3).

The concept of multimorphic cancer pain: the cornerstone of early supportive care to be integrated into public health policy

Definition of supportive care and palliative care

It appears relevant to us to integrate this concept of multimorphic cancer pain as one of the key elements in the healthcare system, giving access to early supportive care. As soon as the diagnosis of cancer has been made, and not solely after the diagnosis of metastatic progression, and thus even in a period of remission, supportive care must be envisaged as pain can be present independently of the progression of cancer for the reasons mentioned above. Nevertheless, the gap between cancer patients’ needs and supportive care received is evolving and growing worldwide [42, 43].

Terminology is of the greatest importance when proposing an innovative model of cancer pain management [44], since the beginning of the 1990s, several definitions of supportive care, palliative care and other associated care concepts have been used and are still debated [45]. In particular, the terms ‘supportive care’ and ‘palliative care’ are often assimilated or confused.

For supportive care, we retain the definition given as early as 1994 by Page: ‘the provision of the necessary services for those living with or affected by cancer to meet their informational, emotional, spiritual, social, or physical needs during their diagnostic, treatment, or follow-up phases encompassing issues of health promotion and prevention, survivorship, palliation, and bereavement. In other words, supportive care is anything one does for the patient that is not aimed directly at curing his disease but rather is focused at helping the patient and family get through the illness in the best possible condition’ [45]. Supportive care in cancer is thus the prevention and management of the adverse effects of cancer and its treatment (including rehabilitation and secondary cancer prevention) from diagnosis, through survivorship, and to end-of-life care [46].

To implement supportive care in patient-centred care [47, 48], communication is thus crucial and based on conversations in a longitudinal care relationship. The first step is a comprehensive assessment of the different aspects of the patient’s life, including the physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects to master the challenges of communication and decision-making [49, 50]. This care continues until the end-of-life, nevertheless, when a cure is no longer possible, it is then integrated into palliative care [51, 52], which we consider to be a full entity within supportive cancer care. Palliative care takes into account the conditions of the end-of-life, including care for the bereaved (Fig. 3) [53]. Whilst being aware that certain studies have shown the rather negative impact of the term ‘palliative’ on a number of aspects [52, 54, 55], unlike the term ‘supportive’.

Pain within supportive care

It appears relevant to us to integrate this concept of multimorphic cancer pain as one of the main elements in a healthcare system, capable of obtaining access to early supportive care, at the time of cancer diagnosis, as pain can be present independently of the progression of the condition for the reasons mentioned above.

In France, pain management—throughout the pathway, including in the post-cancer period—has been identified as one of the four types of supportive care forming the common core, and two analgesic techniques have been integrated into complementary supportive care: intrathecal analgesia and hypnoanalgesia [56]. Management of cancer pain is thus stated as being a priority within the supportive care on offer. But we believe that without significant change to the approach to pain management, and without the accompaniment of real structuring in our healthcare systems, it is unlikely that cancer pain management will improve, as shown in the studies of the last 50 years on the proportion of patients with pain linked to cancer [57, 58].

The advantages of early supportive care

In terms of cancer, the implementation of interdisciplinary supportive care should be carried out as early as possible, as soon as the diagnosis has been made and this, in a systematic manner [38, 59]. The creation of early palliative care since the first foundation study by Temel et al. is now largely relayed by wide-ranging clinical trials exploring the different models of early palliative care, even including those outside the cancer field and instead in the chronic illness field [28, 29]. Depending on the trials, the benefits observed from the implementation of early supportive care are improved quality of life, patient satisfaction, the drawing up of advance directives, decreased hospitalisations, reduced healthcare costs, increased end-of-life care levels at home, increased overall survival or decreased incidence of depression and refractory symptoms (including pain) or a persistent decrease in the exhaustion of carers [30, 60]. Early implementation of this type of care supposes that there is a full assessment of the patient, understanding of the illness and its prognosis and identifying the objectives of the care so as to reduce the number of transitions in care between hospitalisation, consultations and care [61, 62].

Integrating supportive care into the overall management of patients with/or who have had cancer

Several studies based on the addition of palliative care to standard care in different contexts have shown that this addition led to significant improvements for patients [60]:

Inpatient palliative care model

A study of this model in advanced chronic pathologies (in particular cancerology, 1/3 of patients had cancer) revealed a positive impact on patient communication, patient satisfaction, the overall cost of the hospitalisation and the number of deaths during hospitalisation [63]. On the other hand, no effect was observed on quality of life (including the symptoms) or overall survival, probably because of the late introduction of palliative care.

Home-based palliative care model

This model has been studied in patients with a prognosis of less than 1 year (including 40% of cancer patients) [64]. Although a positive impact was observed on emergency hospitalisations, the duration of hospitalisation and its cost, there were more deaths at home.

Outpatient clinic palliative care model

Integrating palliative interventions throughout the follow-up and treatment of cancer by a nurse, with telephone follow-up, made it possible to improve quality of life and depression scores, management of symptoms and the tendency to extend the median duration of overall survival (14 months vs 8.5, not significant) without increasing costs [31, 65]. In addition, the improvement in the median for overall survival depended on the earliness of the supportive care intervention (on diagnosis 18.3 months vs 11.8 at 3 months from diagnosis, risk of the death hazard ratio of 0.72 at 1 year, p = 0.003).

Inpatient and outpatient palliative care model

Temel et al. monitored for 3 months the patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (mNSCLC) [32]. The addition of a monthly supportive care consultation to standard cancer care improved quality of life, with less depression and thymic disorders, increased median overall survival (11.6 with intervention vs 8.9 months without intervention) and decreased healthcare costs.

Overall palliative care model (outpatient clinic, inpatient and home settings)

Follow-up of 393 patients with advanced cancer, all sub-groups of patients with early interventions presented significant differences in relation to management without palliative care for all the parameters studied, resulting in a better quality of life, and improved symptoms and care satisfaction [66]. Another study in such patients showed that early palliative care increased satisfaction with care in caregivers [67].

Thus, in addition to the advantages of early intervention, there is also the impact of an interdisciplinary inpatient palliative team as a complement to the standard care provided by the specialist teams for the pathology. Progression towards these optimised interdisciplinary collaborations requires education and training programmes, such as those implemented by the Oncology Provider Pain Training program (OPPT) to accompany it [68]. Innovative models of palliative care have been experienced in several countries like Canada, United Kingdom, New Zealand or Australia, defining the key conditions for success in terms of organisation, tools, culture, roles to play within interdisciplinary caregivers community or training through a comprehensive approach [69].

Integrating acute and long-term care has been experimented and implemented for people with disabilities and chronic illnesses [70]. From the outset, the word integration has covered a wide variety of concepts. The so-called integrative oncology, which makes possible a permanent exchange between oncology teams and the interdisciplinary teams of supportive care as soon as the diagnosis has been made and throughout the care pathway, has been implemented differently depending on local organisations and the means implemented [27, 30, 53, 60]. Patients can thus benefit from experts in supportive care—and thus in pain—as soon as it becomes necessary and from teams that are not external to the management protocol. In addition, it has been observed that this type of organisation, quite logically, makes it possible to gain a considerable amount of time on a day-to-day basis (170 mins/day) for oncologists, allowing them to devote themselves to their specialisation and the treatment of cancer [27].

On the other hand, Hui et al. have reviewed the pros and cons of four major conceptual models of integration [27]: (I) the time-based integration model governed by chronological criteria; (II) the provider-based model with an increase in specialised palliative care; (III) the issue-based model based on either solo practice, congress (oncologist-driven multidisciplinary management) or integrated care (oncology/supportive/palliative care interdisciplinary management with multidisciplinary specialised support) approaches and (IV) the system-based model governed by the onset of clinical events. As a result, none of these models could be promoted in a global context because of tremendous heterogeneity in healthcare systems, patient populations, resource availability, clinician training and the perception of palliative care [27].

To counteract this conclusion, the model of integration must define the core of the integrated care system and the specialised satellites. Because of the need for early implementation of supportive care, variants of the time-, provider- and system-based models must be avoided as they postpone the full intervention of supportive care. The issue-based model may be the settlement of a new model of integration but it has to be fully integrated into a wider vision of the disease course. In this context, and considering the importance of communication, assessments and education, we propose an integrated care system model offering the supportive environment and personalised relationship, with specialised satellites which are cancer related but also related to the main chronic pathology as a whole. Unfortunately, non-cancer patients with a chronic pathology are often more subject to cancer than patients with non-chronic pathologies and vice versa. This type of model must be simple to implement, and it must satisfy local organisational constraints.

The concept of supportive medicine (Fig. 4)

Previous studies, like the different models proposed in integrative oncology, are based on adding supportive care to the standard curative care, at different times in the illness. By extension, and given the clinical proof observed through the implementation of supportive oncological care, for us, supportive medicine is an operational response to the hyperspecialisation, which makes medicine so efficient nowadays, but which modifies the different roles played by the different actors along the disease course.

Integrative model of supportive medicine for the management of severe chronic disease of in- or out-patients. Specialised pathology teams may include, for example for cancer patients, surgery, radiotherapy, oncology and other specific system and organ teams. The interdisciplinary supportive care team may include supportive/palliative care specialists (specialised clinicians and nurses, clinical pharmacist) and a resident or on an as-needed basis intervention specialists (such as an intrathecal drug delivery system specialist or neurosurgeon), psychologist/psychiatrist and complementary integrative therapy specialist (e.g. nutritionist, acupuncturist). The home care team may include the patient’s general practitioner, community pharmacist, local nurse and other caregivers

We believe that in parallel to the specific management of cancer or chronic conditions, an exhaustive model focusing on specialised, advance management of the symptoms with a sometimes major impact in the care pathway (pain, fatigue, depression, malnutrition, etc.), and other support activities (dietary, psychological and physical well-being, socio-environmental aspects, etc.) could be set up without major upheaval to healthcare structures. With this comprehensive, transdisciplinary and exhaustive approach, as soon as a chronic condition is diagnosed in a specialised centre, the intervention of an interdisciplinary supportive care team as part of the continued relations between those taking part should make it possible to optimise the healthcare pathway and the prevention of avoidable complications, all whilst also avoiding extended hospitalizations and encouraging a significant level of in-home care (Fig. 4). This approach also makes it possible to establish a functional and synergic link between specialists of the disease in question, organ specialists and the teams intervening in-home, preventing management from being divided between specialists. On discharge from the establishment, this follow-up can persist through the supportive care team by means of regular contacts with the private practice care networks, with benefits for the patient in terms of quality of care, and in the use of resources [71].

One of the examples of the benefits of this follow-up is given, in terms of communication with the patients and education about their illness and its overall management, through the integration of clinical pharmacy into the care pathway—as was shown from the outset in English-speaking countries [72]. This specialisation has developed in other countries with the same benefits in terms of clinically relevant and well-accepted optimization of medicine use [73, 74], leading to it being recognised in new countries [75,76,77].

Integrating clinical pharmacists into clinical departments allows them to work with clinicians, healthcare teams and patients, as well as their friends and family. This integration has played a part in fluidifying the healthcare pathway, to the satisfaction of patients, thus strengthening the private practice-hospital link, as well as reducing expenditure [78], with the activities of clinical pharmacy not being limited solely to drug conciliations [79,80,81,82]. This model, developed in supportive care units as part of their interdisciplinarity, is seen as a source of efficiency, with the clinical pharmacist intervening, for example by telephone for the follow-up and adjustment of patients who have had a major modification to their analgesic treatment, thus avoiding consultations and journeys for patients for titrations, for example [82]. This breaks with the more centralised models for deployment from hospital pharmacies, becoming a means of offering adaptability and personalization of the classic clinical pharmacy offer, as well as developing communication with the patients (the treatment of symptoms being a much-appreciated point of entry) as their education, throughout the healthcare pathway.

Dividing up supportive medicine in this way can also bring about collaboration and synergies, in addition to the general practitioners, between local specialists in complementary therapies and nurses, and community pharmacists as a means of reinforcing home-based supportive care, and creating a full home care team to set up local proactive care management with an obviously more flexible relationship than between institution teams. Several studies have thus shown the effectiveness of integrating community pharmacists into chronic disease management programmes and health promotion [83]. In order to provide a rapid and effective response in home-based supportive care, telemedicine is also an opportunity that should not be neglected when developing supportive care, as networks have been set up in several countries [84,85,86,87,88]. Telemedicine facilitates good quality, fast advisory opinions based on questioning and examining the patient (via more detailed questions and visual support), without removing the need for a face-to-face consultation as soon as possible, if necessary.

Implementing this transversal supportive medicine-type model, bringing together different specialists in the management of symptoms (algology, psychology, nutrition, re-education, other complementary therapies, etc.) in patients with chronic conditions could be progressive. The setup is completed with the time to cover exhaustively the department’s services in order to respond to the different expectations of patients, as much within establishments as not [89].

This type of supportive medicine model is a relevant response to the constant development in the levels of over-specialisation in the management of chronic conditions such as cancer and makes it possible to provide the right expertise, to the right patient, by the right teams and at the right time. In addition, this type of structure makes it possible to implement new information and communication technologies for the follow-up of patients with serious chronic conditions in their homes, however, distant and inaccessible they may be.

The supportive care department in relation to the specialised chronic disease team provides a simple integrative model of chronic disease care relying on an interdisciplinary relationship. The development of supportive medicine can lead to an intra-transdisciplinary relationship, all for the benefit of patients.

Conclusions

Given the difficulties still present in the management of cancer pain, increasingly considered as a chronic condition, the concept of multimorphic pain is an innovating approach enhancing new dimensions to optimise cancer pain comprehension and management, including in the most complex situations. It provides the essential steps to better understand this specific entity, and the essential tools to better manage all kind of situations through each patient’s cancer care course.

However, this concept of multimorphic pain cannot be solely and exclusively developed on its own: it has to be strengthened and carried out by a strong determination to develop new and sustainable strategies in diseases management. We believe that integrating supportive medicine to cancer and serious chronic diseases pathway can be a key operational response, in parallel to the constant hyperspecialisation of medicine. The large benefits of such an approach will positively impact patients, caregivers and beyond healthcare systems.

References

Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, de Conno F, Filbet M, Foubert AJ, Cohen R, Dow L (2009) Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol 20:1420–1433. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp001

Valeberg BT, Rustøen T, Bjordal K, Hanestad BR, Paul S, Miaskowski C (2008) Self-reported prevalence, etiology, and characteristics of pain in oncology outpatients. Eur J Pain 12:582–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.09.004

Institut national du Cancer (INCA) (2012) Synthèse de l’enquête nationale 2010 sur la prise en charge de la douleur chez des patients adultes atteints de cancer. www.e-cancer.fr/content/download/63502/571325/file/ENQDOUL12.pdf. Accessed 17 July 2018

Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, Deandrea S, Bandieri E, Cavuto S, Apolone G (2014) Quality of cancer pain management: an update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:4149–4154. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0383

Breuer B, Chang VT, Von Roenn JH et al (2015) How well do medical oncologists manage chronic cancer pain? A national survey. Oncologist 20:202–209. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0276

Mayor S (2000) Survey of patients shows that cancer pain still undertreated. BMJ 321:1309–1309. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7272.1309/b

MacDonald N, Ayoub J, Farley J, Foucault C, Lesage P, Mayo N (2002) A Quebec survey of issues in cancer pain management. J Pain Symptom Manag 23:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00374-8

Hsieh RK (2005) Pain control in Taiwanese patients with cancer: a multicenter, patient-oriented survey. J Formos Med Assoc 104:913–919

Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G (2008) Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 19:1985–1991. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn419

Portenoy R, Koh M (2010) Cancer pain syndromes. In: Press CCU, Bruera E, Portenoy RK (eds) Cancer pain. Assessment and management, vol 4. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 53–88

Higginson IJ, Murtagh FEM (2010) Cancer pain epidemiology. In: Bruera E, Portenoy RK (eds) Cancer pain. assessment and management, vol 3. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 37–52

National Cancer Institute Surveillance, epidemilogy, and end results program (2017) Annual Report to the Nation 2017: Special Section: Survival. https://seer.cancer.gov/report_to_nation/survival.html. Accessed 17 July 2018

Institut National du Cancer (2010) Survie attendue des patients atteints de cancers en France : état des lieux. www.e-cancer.fr/content/download/96009/1022035/file/RAPSURVIE10. Accessed 17 July 2018

Institut de veille sanitaire (2016) Survie des personnes atteintes de cancer en France métropolitaine, diagnostiquées entre 1989 et 2010, suivies jusqu’en 2013. http://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr/Dossiers-thematiques/Maladies-chroniques-et-traumatismes/Cancers/Surveillance-epidemiologique-d

Fallon M, Giusti R, Aielli F, Hoskin P, Rolke R, Sharma M, Ripamonti CI, ESMO Guidelines Committee (2018) Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO clinical practice guidelines†. Ann Oncol 29:166–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy152

Bennett MI, Eisenberg E, Ahmedzai SH, Bhaskar A, O’Brien T, Mercadante S, Krčevski Škvarč N, Vissers K, Wirz S, Wells C, Morlion B (2018) Standards for the management of cancer-related pain across Europe. A position paper from the EFIC Task Force on Cancer Pain. Eur J Pain 23:660–668. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1346

Delorme T, Wood C, Bartaillard A, et al. (2004) [2003 clinical practice guideline: standards, options and recommendations for pain assessment in adult and children with cancer]. http://www.sfetd-douleur.org/sites/default/files/u3/docs/sorevaluation.pdf. Accessed 17 July 2018

Raffa RB, Pergolizzi JV (2014) A modern analgesics pain “pyramid”. J Clin Pharm Ther 39:4–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12110

Wilson J, Stack C, Hester J (2014) Recent advances in cancer pain management. F1000Prime Rep 6:10. https://doi.org/10.12703/P6-10

Hochberg U, Elgueta MF, Perez J (2017) Interventional analgesic management of lung cancer pain. Front Oncol 7:17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2017.00017

Chwistek M (2017) Recent advances in understanding and managing cancer pain. F1000Research 6:945. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.10817.1

Candido KD, Kusper TM, Knezevic NN (2017) New cancer pain treatment options. Curr Pain Headache Rep 21:12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-017-0613-0

Carvajal G, Dupoiron D, Seegers V, Lebrec N, Boré F, Dubois PY, Leblanc D, Delorme T, Jubier-Hamon S (2018) Intrathecal drug delivery systems for refractory pancreatic cancer pain. Anesth Analg 126:2038–2046. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002903

Bernstein JH (2015) Transdisciplinarity: a review of its origins, development, and current issues. Journal of Research Practice,11, Article R1. http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/510/412 Accessed 17 July 2018

Choi BCK, Pak AWP (2007) Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 2. Promotors, barriers, and strategies of enhancement. Clin Invest Med 30:224–232

Choi BCK, Pak AWP (2006) Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clin Invest Med 29:351–364

Hui D, Bruera E (2015) Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 4:89–98. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.04.01

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733–742. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1000678

Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A et al (2017) Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 35:834–841. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5046

Zhi WI, Smith TJ (2015) Early integration of palliative care into oncology: evidence, challenges and barriers. Ann Palliat Med 4:122–131. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.07.03

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Li Z, Dionne-Odom JN, Frost J, Dragnev KH, Hegel MT, Azuero A, Ahles TA (2015) Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33:1438–1445. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362

Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Lynch TJ, Lennes IT, Dahlin CM, Pirl WF (2011) Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 29:2319–2326. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) (2016) Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health#integrative. Accessed 17 July 2018

Strada E, Portenoy R (2017) Psychological, rehabilitative, and integrative therapies for cancer pain. Uptodate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/psychological-rehabilitative-and-integrative-therapies-for-cancer-pain#H44713544. Accessed 17 July 2018

Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG et al (2017) Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 67:194–232. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21397

Raphael J, Hester J, Ahmedzai S, Barrie J, Farqhuar-Smith P, Williams J, Urch C, Bennett MI, Robb K, Simpson B, Pittler M, Wider B, Ewer-Smith C, DeCourcy J, Young A, Liossi C, McCullough R, Rajapakse D, Johnson M, Duarte R, Sparkes E (2010) Cancer pain: part 2: physical, interventional and complimentary therapies; management in the community; acute, treatment-related and complex cancer pain: a perspective from the British Pain Society Endorsed by the UK Association of Palliative Medicine and the Royal College of General Practitioners: Table 1. Pain Med 11:872–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00841.x

Ernst E, Pittler MH, Wider B, Boddy K (2007) Complementary therapies for pain management: an evidence-based approach. Complement Ther pain Manag an evidence-based approach

Bruera E, Hui D (2010) Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol 28:4013–4017. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5618

Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, Fiscella K, Hoerger M, Tancredi DJ, Xing G, Gramling R, Mohile S, Franks P, Kaesberg P, Plumb S, Cipri CS, Street RL Jr, Shields CG, Back AL, Butow P, Walczak A, Tattersall M, Venuti A, Sullivan P, Robinson M, Hoh B, Lewis L, Kravitz RL (2016) Effect of a patient-centered communication intervention on oncologist-patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 3:92–100. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4373

Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M (2010) It’s not over when it’s over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med 40:163–181. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.40.2.c

Lemaire A, Plançon M, Bubrovszky M (2014) Kétamine et dépression: vers de nouvelles perspectives thérapeutiques en soins de support ? Psycho-Oncologie 8:59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11839-014-0453-7

Jordan K, Aapro M, Kaasa S, Ripamonti CI, Scotté F, Strasser F, Young A, Bruera E, Herrstedt J, Keefe D, Laird B, Walsh D, Douillard JY, Cervantes A (2018) European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol 29:36–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx757

Bruera E, Hui D (2016) Palliative care and supportive care. In: Bruera E, Higginson I, von Gunten CF, Morita T (eds) Textbook of Palliative Medicine and Supportive Care, Secong edn. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, pp 97–102

Hui D (2014) Definition of supportive care. Curr Opin Oncol 26:372–379. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCO.0000000000000086

Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M et al (2013) Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer 21:659–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1564-y

Consensus on the Core Ideology of MASCC (2003). Definition of Supportive Care. http://www.mascc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view¼article&id=493:mascc-strategic-plan&catid=30:navigation. Accessed 17 July 2010

Frampton S, Guastello S, Brady C, et al. (2008) Patient Centered Care Improvement Guide. Planetree, Inc. and Picker Institute. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PatientCenteredCareImprovementGuide.aspx. Accessed 17 July 2018

World Health Organization (2016) Framework on integrated people-centred health services. Sixty-ninth World Health Assembly. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_39-en.pdf?ua=1&ua=1. Accessed 17 July 2018

Dy SM, Isenberg SR, Al Hamayel NA (2017) Palliative care for cancer survivors. Med Clin North Am 101:1181–1196. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MCNA.2017.06.009

van Hecke O, Torrance N, Smith BH (2013) Chronic pain epidemiology - where do lifestyle factors fit in? Br J Pain 7:209–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463713493264

World Health Organization (2018) Palliative care. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care. Accessed 17 July 2018

Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, Nguyen L, Chacko R, Li Z, Fadul N, Scott C, Thornton V, Coldman B, Amin Y, Bruera E (2011) Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 16:105–111. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0161

Cherny NI, Catane R, Kosmidis P (2003) ESMO takes a stand on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol 14:1335–1337. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdg379

Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, del Fabbro E, Swint K, Li Z, Poulter V, Bruera E (2009) Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name? Cancer 115:2013–2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24206

Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Leighl N, Rydall A, Rodin G, Tannock I, Hannon B (2016) Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ 188:217–227. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.151171

Institut national du cancer (2016) Rapport d’expertise de l’INCa : “Axes opportuns d’évolution du panier de soins oncologiques de support”, octobre 2016. http://www.e-cancer.fr/Expertises-et-publications/Catalogue-des-publications/Axes-opportuns-d-evolution-du-panier-des-soins-oncologiques-de-support-Reponse-saisine. Accessed 17 July 2018

van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, Hochstenbach LMJ, Joosten EAJ et al (2016) Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manag 51:1070–1090.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.340

MHJ VDB-VE, De Rijke JM, Kessels AG et al (2007) Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol 18:1437–1449. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm056

Ferrell B, Sun V, Hurria A, Cristea M, Raz DJ, Kim JY, Reckamp K, Williams AC, Borneman T, Uman G, Koczywas M (2015) Interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag 50:758–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.07.005

Higginson IJ, Booth S (2011) The randomized fast-track trial in palliative care: role, utility and ethics in the evaluation of interventions in palliative care? Palliat Med 25:741–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311421835

Tuggey EM, Lewin WH (2014) A multidisciplinary approach in providing transitional care for patients with advanced cancer. Ann Palliat Med 3:139–143. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2014.07.02

Weissman DE, Meier DE (2011) Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the center to advance palliative care. J Palliat Med 14:17–23. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2010.0347

Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, McGrady K, Beane J, Richardson RH, Williams MP, Liberson M, Blum M, Penna RD (2008) Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 11:180–190. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2007.0055

Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, Seitz R, Morgenstern N, Saito S, McIlwane J, Hillary K, Gonzalez J (2007) Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:993–1000. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x

Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Barnett KN, Brokaw FC, Byock IR, Hull JG, Li Z, Mckinstry E, Seville JL, Ahles TA (2009) The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care 7:75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951509000108

Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, Moore M, Rydall A, Rodin G, Tannock I, Donner A, Lo C (2014) Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383:1721–1730. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2

McDonald J, Swami N, Hannon B, Lo C, Pope A, Oza A, Leighl N, Krzyzanowska MK, Rodin G, le LW, Zimmermann C (2016) Impact of early palliative care on caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: cluster randomised trial. Ann Oncol 28:438. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw438

Patel B, Hacker E, Murks C, Ryan C (2016) Interdisciplinary pain education: moving from discipline-specific to collaborative practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 20:636–643. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.CJON.636-643

Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (2013) Innovative models of integrated hospice palliative care, the way forward initiative: an integrated palliative approach to care. http://www.hpcintegration.ca/media/40546/TWF-innovative-models-report-Eng-w

Leutz WN (1999) Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Q 77:77–110 iv–v

Baldonado A, Hawk O, Ormiston T, Nelson D (2017) Transitional care management in the outpatient setting. BMJ Qual Improv Reports 6:u212974.w5206. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u212974.w5206

Whitney HA, Nahata MC, Thordsen DJ (2008) Francke’s legacy—40 years of clinical pharmacy. Ann Pharmacother 42:121–126. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1K660

Spinewine A, Dhillon S, Mallet L, Tulkens PM, Wilmotte L, Swine C (2006) Implementation of ward-based clinical pharmacy services in Belgium—description of the impact on a geriatric unit. Ann Pharmacother 40:720–728. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1G515

Ise Y, Morita T, Katayama S, Kizawa Y (2014) The activity of palliative care team pharmacists in designated cancer hospitals: a nationwide survey in Japan. J Pain Symptom Manag 47:588–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.008

Somers A, Spinewine A, Spriet I, Steurbaut S, Tulkens P, Hecq JD, Willems L, Robays H, Dhoore M, Yaras H, vanden Bremt I, Haelterman M (2018) Development of clinical pharmacy in Belgian hospitals through pilot projects funded by the government. Acta Clin Belg 74:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17843286.2018.1462877

Haute Autorité de Santé (2015) Initiative des HIGH 5s. Medication Reconciliation. Rapport d’expérimentation sur la mise en oeuvre de la conciliation des traitements médicamenteux par neuf établissements de santé français. https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2015-11/rapport_dexperimentation_sur_la_mise_en_oeuvre_conciliation_des_traitements_medicamenteux_par_9_es.pdf. Accessed 17 July 2018

Dickman A (2010) The place of the pharmacist in the palliative care team. Eur J Palliat Care 17:133–135

Fulcrand J, Dujardin L, Lemaire A (2017) Pharmacie clinique au sein d’un pôle médicochirurgical : l’expérience originale du centre hospitalier de Valenciennes - Techniques hospitalières. Tech Hosp médico-sociales Sanit 766:16–19

Patel H, Gurumurthy P (2017) Implementation of clinical pharmacy services in an academic oncology practice in India. J Oncol Pharm Pract 107815521773968:369–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078155217739684

Jackson K, Letton C, Maldonado A, Bodiford A, Sion A, Hartwell R, Graham A, Bondarenka C, Uber L (2018) A pilot study to assess the pharmacy impact of implementing a chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting collaborative disease therapy management in the outpatient oncology clinics. J Oncol Pharm Pract 107815521876562:847–854. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078155218765629

Fulcrand J, Delvoye J, Boursier A, Evrard M, Dujardin L, Ferret L, Barrascout E, Lemaire A (2018) Place du pharmacien clinicien dans la prise en charge des patients en soins palliatifs. J Pain Symptom Manag 56:101–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.343

Dujardin L, Fulcrand J, Lemaire A (2017) Pharmacie clinique en soins de support et palliatifs. La synergie du binôme médecin-pharmacien en consultation. Tech Hosp médico-sociales Sanit 766:13–15

George PP, Molina JAD, Cheah J et al (2010) The evolving role of the community pharmacist in chronic disease management - a literature review. Ann Acad Med Singap 39:861–867

Lemaire A (2014) TéléPallia : La télémédecine au service du déploiement des Equipes mobiles de soins palliatifs en Etablissements d’hébergement pour personnes âgées dépendantes, en France Rev Int soins palliatifs 29:145. https://doi.org/10.3917/inka.144.0145

Ohannessian R, Guettier C, Lemaire A, Denis F, Ottavy F, Galateau Salle F, Gutierrez M (2017) L’utilisation de la télémédecine pour la prise en charge du cancer en France en 2016. Eur Res Telemed / La Rech Eur en Télémédecine 6:44. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURTEL.2017.02.037

European Parliament and Council. Decision no 1350/2007/ec of the European parliament and of the council of 23 October 2007 establishing a second programme of Community action in the field of health (2008–13). http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2007:301:0003:0013:EN:PDF. Accessed 17 July 2018

Rojahn K, Laplante S, Sloand J, Main C, Ibrahim A, Wild J, Sturt N, Areteou T, Johnson KI (2016) Remote monitoring of chronic diseases: a landscape assessment of policies in four European countries. PLoS One 11:0155738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155738

Krupinski E, Nypaver M, Poropatich R, Ellis D, Safwat R, Sapci H (2002) Telemedicine/telehealth: an international perspective. Clinical applications in telemedicine/telehealth. Telemed J e-Health 8:13–34. https://doi.org/10.1089/15305620252933374

Sardin B, Lemaire A, Terrier G et al (2014) Appliquer la culture palliative au champ des maladies chroniques : le concept de médecine exhaustive. Éthique et santé 11:138–151

Acknowledgements

Support was provided by Xavier Amores M.D. and Viorica Braniste M.D. & Ph.D. (Kyowa Kirin) and Robert Campos Oriola Ph.D and Marie-Odile Barbaza MD. (Auxesia) for manuscript preparation.

Funding

This article was funded by Kyowa Kirin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Antoine Lemaire reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin France, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin International, Mundi Pharma, Grunenthal and Takeda, personal fees from Mylan, and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin France, Archimèdes Pharma, Teva, Prostrakan, outside the submitted work. Brigitte George reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Mundipharma, non-financial support from Grunenthal and Kyowa Kirin, outside the submitted work; participation to a clinical study without honoraria from Bouchara. Caroline Maindet reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Mundipharma, and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, Grunenthal, Hospira, Takeda, and Janssen Cilag, outside the submitted work. Alexis Burnod reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work; non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, outside the submitted work. Gilles Allano reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Grunenthal, Mundipharma and Medtronic, and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, outside the submitted work. Christian Minello reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Takeda, and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, Mundi Pharma, Mylan Pharma and Grunenthal, outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lemaire, A., George, B., Maindet, C. et al. Opening up disruptive ways of management in cancer pain: the concept of multimorphic pain. Support Care Cancer 27, 3159–3170 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04831-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04831-z