Abstract

Purpose

Complementary integrative therapies (CITs) correspond to growing demand in patients with cancer-related pain. This demand needs to be considered alongside pharmaceutical and/or interventional therapies. CITs can be used to cover certain specific pain-related characteristics. The objective of this review is to present the options for CITs that could be used within dynamic, multidisciplinary, and personalized management, leading to an integrative oncology approach.

Methods

Critical reflection based on literature analysis and clinical practice.

Results

Most CITs only showed trends in efficacy as cancer pain was mainly a secondary endpoint, or populations were restricted. Physical therapy has demonstrated efficacy in motion and pain, in some specific cancers (head and neck or breast cancers) or in treatments sequelae (lymphedema). In cancer survivors, higher levels of physical activity decrease pain intensity. Due to the multimorphism of cancer pain, certain mind-body therapies acting on anxiety, stress, depression, or mood disturbances (such as massage, acupuncture, healing touch, hypnosis, and music therapy) are efficient on cancer pain. Other mind-body therapies have shown trends in reducing the severity of cancer pain and improving other parameters, and they include education (with coping skills training), yoga, tai chi/qigong, guided imagery, virtual reality, and cognitive-behavioral therapy alone or combined. The outcome sustainability of most CITs is still questioned.

Conclusions

High-quality clinical trials should be conducted with CITs, as their efficacy on pain is mainly based on efficacy trends in pain severity, professional judgment, and patient preferences. Finally, the implementation of CITs requires an interdisciplinary team approach to offer optimal, personalized, cancer pain management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pain is a subjective symptom defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” [1]. Cancer-related pain felt by patients is multimorphic and presents four dimensions (sensory-discriminatory, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral; Fig. 1). Thus, pain is expressed by the “body itself” (suffering experienced by the body) and/or by the “mind” (e.g., depression), and it leads to physical and psychological complications associated with a decrease in patients’ vitality and quality of life. Pain impacts social relationships with relatives and caregivers and encourages certain relational behaviors [2, 3]. The behavior of people towards pain is transcultural and is influenced by patients’ beliefs and culture.

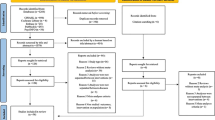

Cancer pain is one of the major burdens for survivors along with depression and fatigue and has a strong impact on quality of life [4]. Nevertheless, it remains underdiagnosed, poorly evaluated, and undertreated [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. This is mainly due to healthcare professionals’ insufficient knowledge of cancer-related pain, which impedes quality management of this multimorphic disease [13, 14]. The cancer pain requires multimodal, targeted, dynamic, and personalized management (Fig. 2) including, in addition to pharmaceutical strategies and/or interventional therapies, the use of non-pharmacologic, non-invasive approaches, called complementary integrative therapies (CITs), especially when pain control becomes hazardous [15,16,17,18,19]. Due to the multimorphic character of cancer pain, patients experience frequent changes/exacerbations related to evolution and treatment of cancer, and to disruptive events (concomitant treatments, associated disease pains, comorbidities, and complications, modifications of the environment) (Fig. 3). Repeated inappropriate management of these exacerbations may create a vicious circle impacting the four dimensions of cancer pain (Fig. 4). On the other hand, several CITs are already used by cancer patients on their own [20,21,22] and often without discussing their use with their physician [23]. Thus, clinicians have to handle appropriately this possible desire [24], especially in patients with poorly treated cancer-related pain.

CITs may directly act on certain aspects of cancer pain (Fig. 5). Their initiation allows not only supporting patients in their daily life (at their demand) but also to prevent or avoid worsening chronic cancer-related pain within a holistic strategy.

This review is an endeavor to highlight several non-pharmacologic, non-invasive interventions with proven efficacy on pain, or at least trends for it. Facing cancer patients often suffering from undertreated pain, at their consultations, the authors have carried out a critical reflection based on a literature analysis and their clinical practice. For each domain, the literature search was set up on recent reviews and the latest publications on Medline.

Background to complementary and integrative therapies

Due to cancer’s potential life-threatening character, cancer-related pain has long been considered as a minor secondary endpoint in clinical trials, and, when studied, it was mainly along with or as a component of quality of life. Thus, there is little room for clinical trials in mainstream pain therapies, and even less for CITs. Only trends for CIT efficacy or minor evidences of it have been obtained or even searched for in cancer-related pain. Furthermore, only few studies have addressed these issues in a longitudinal fashion, comparing patients with and without a history of cancer to differentiate between the effects of cancer and those of aging [25].

The implementation of the CITs requires the participation of specialists and of an interdisciplinary team to propose the appropriate complementary therapy to patients and answer any questions they may have. CITs can be classified in natural products (e.g., herbs, vitamins and minerals, probiotics), Mind and body practices (procedures or techniques administered or taught, e.g., yoga, chiropractic and osteopathic manipulation, meditation, and massage therapy; and other practices such as acupuncture, relaxation techniques, tai chi/qi gong, healing touch, hypnotherapy), and other complementary health approaches (e.g., Ayurvedic medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, homeopathy, and naturopathy) [26]. The effective CITs on pain address different dimensions of pain and often overlap.

Certain factors that initially appear non-modifiable strongly influence chronic pain and must be taken into account when envisaging the best cancer pain management [27]. These factors include age, sex, cultural and socio-environmental aspects, and inherited factors.

In this article, CITs potentially effective against multimorphic cancer pain are presented according to the dimensions of chronic pain they target primarily. The authors chose to focus mainly on mind and body practices, and not to cover the other two aspects (natural products and other complementary health approaches).

Sensory-discriminatory dimension

Physical exercise

Physical activity acts at a sensory-discriminatory level [28,29,30,31] and appears to both reduce stress and anxiety [32], and improve depression [33], as shown in general elderly populations [34]. The type of exercise must be adapted to the patient’s physical condition and limits in order to avoid damage [35]. Thus, for patients with advanced disease, the physical therapist will look for a task to be completed instead of focusing on correction of individual impairments.

Most studies on the impact of physical exercise in cancer patients have focused on its benefit in terms of survival and quality of life, with cancer-related pain being a minor secondary endpoint. Nevertheless, physical exercise modifies the levels of circulating hormones (e.g., insulin, estrogens) and cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), and induces other metabolic changes [36]. The changes in adipokine balance may impact the nociceptors with potential benefits in pain control [37].

Physical exercise (including community-based exercise programs, strength or resistance training, walking, cycling, stretching) has been associated with improved overall psychological, behavioral, and physical conditions [2, 36, 38, 39]. Higher levels of physical activity are associated with lower pain levels [40]. The efficacy of progressive resistance exercise training has been demonstrated in shoulder pain and disability and upper extremity muscular strength and endurance in head and neck cancer survivors [28]. Few other studies have shown a positive impact on pain of physical exercise combined with cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) or lifestyle programs [41,42,43]. Physical exercise must be tailored to obtain appropriate duration and intensity [31], but treatment-related activity barriers often need to be removed [44].

Physical therapy

Of the various applications of physical therapy, multifactorial physical therapy and active exercise are effective for treating postoperative pain after breast cancer treatment and impaired range of motion [45]. No such results have yet been obtained with passive mobilization, stretching, or myofascial therapy as part of the multifactorial treatment [45].

Therapeutic massage has been poorly studied in cancer-related pain [46]. Exercise and manual lymphatic drainage have shown efficacy for lymphedema [38], as well as massage therapy in patients with metastatic bone pain [47]. In patients receiving chemotherapy, massage was beneficial for reducing pain, inducing physical relaxation, and improving mood disturbances and fatigue [48]. The significant effect of massage in reducing immediate pain was associated with an important decrease in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use, and a trend for reduced opioid use. The evidence for analgesic effects of massage in non-cancer and cancer patients is nevertheless debated [49,50,51]. Massage may be perceived negatively by some women due to altered body image, modesty, or ethnocultural considerations [45]; on the other hand, tai chi/qi qong is more accepted nowadays in Western countries than it used to be [52]. Healing touch (energy therapy with light hand contact) has shown benefits on several symptoms in cancer patients during chemotherapy, especially reducing pain with significant short-term effect (less than a month), compared with the therapist presence alone or standard care [48].

Yoga, tai chi, and qi gong

Even though interest in mind-body interventions such as yoga is growing for minimizing the deleterious effects of cancer-related symptoms [53,54,55,56], few studies have been conducted on pain. In cancer survivors, the variability of yoga efficacy on pain ranged from non-significant to considerable (in two of four studies) [57]. Yoga awareness programs including CBT elements and meditation and breathing exercises improved joint pain in breast cancer survivors [58]. Relaxation, breathing exercises, and/or yoga programs focused on cancer-related pain are often successfully associated with CBT interventions [45]. Furthermore, yoga appeared to be particularly efficient in aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia [58, 59].

Qi gong and tai chi studies have reported positive findings for both physical and psychological functions, including reducing non-cancer pain and perceived stress [60]. In cancer survivors, tai chi and qi gong significantly improved fatigue, sleep difficulty, depression, and quality of life [61, 62], but only a trend for pain improvement was observed. Otherwise, compared to health education control, tai chi did not provide further improvement to pain [63].

Acupuncture

Literature review showed that acupuncture plus drug therapy is more effective than conventional drug therapy alone for cancer-related pain, while the reduction in cancer-related pain with acupuncture alone was not greater than that of conventional drug therapy [64, 65]. Somatic and auricular acupuncture plus drug therapy resulted in benefits in cancer pain, and better quality of life (when measured) without serious adverse effects, the quality of all outcomes being mainly low [64]. A recent meta-analysis showed the efficacy of acupuncture in malignancy-related and surgery-induced pain as part of a multimodal management, but not for chemotherapy- or radiation therapy-induced pain [66]. Acupuncture may be considered for pain related to aromatase inhibitor-associated musculoskeletal symptoms [67,68,69,70]. As for other CITs, high-quality clinical trials with larger sample sizes should dispel any doubt about its efficacy [71].

Electrical nerve stimulation

For more than two decades, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has been used without clear evidence of efficacy in any type of chronic pain, including chronic cancer treatment-related pain. Its effectiveness might be explained by supportive environment or a placebo effect [72, 73]. Clinical experience supports a trend for efficacy in some patients. A new electrocutaneous nerve stimulation device has been designed to “scramble” afferent pain signals and replace them with “non-pain” stimuli through conventional lines of neural transmission (scrambler therapy), above and below the site of pain. Trends for efficacy have been reported in patients with neuropathic or mixed pain [74]. Scrambler therapy has also shown a trend for efficacy in patients with cancer pain (pilot studies) [75, 76].

Emotional dimension

As shown in breast cancer survivors, depression is highly associated with other cancer-related symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and insomnia [77]. Mind-body interventions (e.g., relaxation, meditation, imagery, hypnosis, music therapy, virtual reality) may help relieve depression, stress, anxiety, and other mood disturbances associated with pain, and reduce cancer-related pain [45, 78].

Supportive-expressive group therapy

Of psychological interventions, supportive-expressive group therapy significantly improved cancer pain scores at 12 months compared with usual practice, in a meta-analysis of three studies [79].

Guided imagery

Relaxation with imagery (or mental rehearsal imagery) mainly consists in patients mentally creating a peaceful comfortable physical place. In several studies, there were small to moderate improvements in cancer-related pain; however, these studies were of low methodological quality [80,81,82,83].

Virtual reality

Virtual reality (VR) has been used to manage pain and distress associated with a wide variety of known painful medical procedures, such as burn pain and wound care, chemotherapy, lumbar puncture, and port access in cancer patients, with very few, only mild, short-term side effects [84,85,86,87,88]. VR has been used with success in rehabilitation systems to treat cancer survivors coping with upper body chronic pain [89]. In hospitalized patients, pain relief was obtained with VR in significantly more patients than with control distraction conditions (high-definition, 2D video), and mean pain reduction was significantly greater [90]. Participants immersed in a VR experience reported reduced pain levels, general distress/unpleasantness and a desire to use VR again during painful medical procedures [91].

Hypnosis

During the treatment period, several meta-analyses and randomized clinical trials have shown beneficial effects of hypnosis on cancer-related pain relief, treatment procedures, and concomitant disease (e.g., mucositis), in addition to its activity against distress or anxiety [2, 45, 92]. In survivors, hypnosis has been studied to a lesser extent and a recent study has shown great improvements in symptoms using the Valencia model of waking hypnosis with cognitive-behavioral therapy (VMWH-CBT), including alleviating cancer-related pain [93]. The efficacy of hypnosis is well established and is the only non-invasive CIT recommended in France [94]. Hypnosis has been used in a group therapy context for more than two decades, and greater benefit on pain relief related to advanced breast cancer was reported in highly hypnotizable participants [95,96,97].

Music therapy

Music therapy is either passive or active (i.e., with patient participation in creating live music) and it seems to act through neurologic, psychological, behavioral, and physiologic pathways [45]. The efficacy of interactive or passive music therapy in relieving cancer-related pain is supported by moderate evidence, and music therapy may reduce anesthetic and analgesic consumption and the length of hospitalization [92, 98,99,100,101,102].

Behavioral dimension

Patients with cancer often present frailty and build attitudinal barriers to cancer pain management. Fear of addiction to opioids is the strongest barrier in patients, and these attitudinal barriers are associated with less effective pain control [103]. Attitudinal barriers to pain and the use of analgesics are shared by patients and their family caregivers [104], often based on cultural and religious barriers [105,106,107]. The perceived barriers appear to be significantly higher in Asian patients than Western patients with no differences between other ethnic groups [108, 109].

Mindfulness mediation

During exposure to pain, meditators exhibited modifications on magnetic resonance imaging [110], leading to the conclusion that changes in the perception of pain were facilitated through the cognitive and affective components of the pain matrix, rather than through the sensory properties of pain. Mindfulness-based methods, including mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR, a structured group program), are deemed effective for conditions such as chronic pain by increasing mindfulness and pain acceptance, as well as improving emotional functioning [111,112,113]. MBSR programs have shown effects on some chronic pain conditions, but not all, and compliance with home meditation practice did not favor pain improvement [114]. However, in chronic pain, the benefits of mindfulness-based meditation strategies remain controversial as in recent reviews and meta-analyses pain reduction during treatment was not clearly and unambiguously demonstrated [115, 116]. Considering cancer patients, MBSR has shown benefits on sleep disturbance and fatigue [92], but no clear benefit is established on cancer pain [117, 118]. Relaxation training was found to significantly improve pain and other treatment-related symptoms in a meta-analysis in cancer patients undergoing acute non-surgical cancer treatments [119].

Cognitive dimension

Most of the performed studies focused on both the behavioral and cognitive dimensions of pain and do not distinguish the cognitive dimension solely. Therefore, the interventions presented in this section cover cognitive dimension associated with behavioral one.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs) have a common base of behavioral and cognitive models of psychological disorders and utilize a set of overlapping techniques that can be used to improve chronic pain problems by decreasing patient catastrophizing and increasing patient self-efficacy for managing pain [112, 120, 121]. CBT has proven its efficacy in chronic pain and its cost-effectiveness for several decades [122]. More recently, the third wave of CBT approaches integrate strategies such as mindfulness exercises, acceptance of unwanted thoughts and feelings, and cognitive diffusion [123]. Psycho-education on stress and coping have been added to cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) [124, 125].

CBT, CBSM, or similar mind-body combination interventions produced improved cancer-related pain in most studies [2, 82, 83, 92, 126,127,128,129]. Their effects seem mainly due to improved pain catastrophizing [130]. During post-treatment survivorship, CBT showed some promising results in a small study in improving chronic pain and coping with pain [131].

A recent review found some evidence for potential predictors or moderators of outcomes in contextual CBT for chronic non-cancer pain [132]. Using mindfulness-based interventions, patients with higher psychological distress or a history of depression tended to obtain the greatest improvements in chronic pain [133,134,135]. However, two studies on online interventions of acceptance and commitment therapy found that lower psychological distress led to greater improvements in pain-related interference [136], and found no association between baseline depression diagnosis and outcomes [137]. A study on pre-surgical stress management training in cancer patients revealed no effect on pain, or anxiety and sleep problems [138]. The outcomes of CBT interventions depend on the methodology and approach used (e.g., face-to-face vs online). Nevertheless, such outcomes again emphasize the need for high-quality clinical trials.

Education and communication

Educational interventions are generally defined as information, behavioral instructions, and advice on pain management delivered by a health provider or peer (such as an expert patient) using any medium (for example, verbal, written, taped, or computer-aided) [126]. The intervention significantly improved knowledge and attitudes towards cancer pain and analgesia, but high heterogeneity has been reported [126]. No pain reduction in daily activities or improved medication adherence was observed. In advanced-cancer patients, a combined intervention that included oncologist communication training and coaching for patients improved only patient-centered communication [139]. Conversely, a patient-centered approach combining pain consultations and pain education programs improved pain intensity, daily interference, and adherence to analgesics [140]. Similarly, patient-centered tailored education and coaching improved communication self-efficacy and enhanced patient involvement in care compared to education only, with analgesic adjustment associated with better sustained pain control [141].

Self-management education interventions have been shown to improve pain and other cancer-related symptoms (and quality of life) [142]. Self-management is the capability of a patient to manage pain, analgesic treatments, and the physical and psychological consequences of living with cancer-related pain [19]. However, Howell et al. were not able to determine the components or elements of these interventions impacting the strength of the effects. Different potential levels of intervention may affect pain intensity, such as coaching, nursing support, and the use of a diary on pain intensity and analgesic intake [143, 144].

The systematic use of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measurements with feedback to increase discussions between patients and professionals may improve cancer pain management [145]. However, only modest reductions have been reported in cancer pain intensity when PROs were used with other coaching tools [146, 147]. PROs may be of interest when patients make tradeoffs between opioid side effects, physical activity, cognitive function, and pain relief [148].

Finally, as shown by Street et al., cancer patients who need to communicate with their physician prescribing pain medication are keen to discuss pain-related matters, and state preferences which can elicit changes in their pain management regimen leading to better pain control [149]. In addition to the direct advantages of self-management over attitudinal barriers, truly balanced communication between patients and healthcare teams, leading to informed choice, must be part of the patient healthcare pathway.

In this context, new opportunities are becoming available to cancer patients in geographically dispersed urban and rural oncology practices. Centralized telecare management through physician and nurse or physician and clinical pharmacist [150] collaboration facilitated optimized medication management by assessing symptom response and medication adherence, and providing pain and depression-specific education. This centralized telecare management coupled with automated symptom monitoring resulted in improved pain and depression outcomes in these cancer patients [147, 151]. In this context, digital technologies may soon offer new opportunities of communication, helping patients share individual symptom experiences and goals, thus enhancing tailored care [152]. Regular, balanced communications between patients and their clinicians, as well as within the interdisciplinary team, are thus necessary for long-lasting cancer pain control.

Discussion

Cancer-related pain requires multimodal, targeted, dynamic, and personalized management (Fig. 2), which can include non-pharmacologic, non-invasive approaches, in addition to pharmaceutical strategies and/or interventional therapies. The CITs address the different dimensions of pain and they often overlap (Fig. 5).

Some of the CITs represent alternative therapies already used by cancer patients on their own without informing their health professionals [20, 21, 23]. Their use is often caused by dissatisfaction with conventional medicine, desperation, and compatibility between the philosophy of alternative therapies and their own beliefs [22]. Therefore, there is a need to establish a truly balanced communication between patients and healthcare teams in order to propose the most appropriate CIT and in adequacy with the ethnocultural and sociological expectancies of patients.

On the other hand, healthcare professionals’ attitudes still compromise the delivery of quality care to patients with chronic cancer pain [13]. Primary care physicians report a lack of knowledge in the management of chronic pain in cancer survivors [14]. Because of the multimorphic nature of cancer pain the need for multimodal management, which requires interdisciplinary teams, is another barrier [153]. Six-month educational programs for healthcare professionals, implemented to alleviate these barriers, led to a significant improvement in their knowledge and attitudes resulting in improved cancer pain management [154].

In this context, the personalized management of cancer-related pain is particularly sensitive when proposing CITs to reach optimal holistic care in agreement with patients’ beliefs and preferences [117]. That being said, choosing CIT(s) is complex due to the overlap between cancer-related pain dimensions. Complementary body-oriented therapies for pain, at every stage of the disease, may result in “body” and/or “mind” improvement. In addition, this improvement may parallel an important benefit regarding cancer evolution or quality of life leading to difficulties in recognizing the benefits on cancer-related pain unless specifically designed RCTs are set up. Physical activity thus participates in the increase in overall survival observed in most cancers with a dose-response relationship [36]]. Regular sustained or intense exercise also presents physiological and psychological benefits [31, 155, 156]. Nevertheless, the principles of physical activity vary greatly in randomized clinical trials, and reporting of the exercise actually performed was incomplete [157]. Methodologically stronger clinical trials of CITs are still needed to provide clinicians with accurate resources for managing cancer-related acute pain [158].

Keeping in mind these methodological weaknesses in the available studies, choosing the appropriate CIT(s) may be driven by the dimensions of cancer pain impacted by genuinely balanced communication between patients and healthcare teams. The formalized informed choice must be part of the patient healthcare pathway and evolve as the conditions change. CIT use may result in better acceptance of pharmacologic therapies due to control of adverse effects and overall positive feelings supported by a more constructive patient-health professional relationship [149].

Even though the levels of evidence may sometimes be moderate or low, the improvement in the patients’ overall psychological, behavioral, and physical conditions observed with the different CITs should lead to better-designed RCT to comfort their efficacy if any. The already observed improvements and patients’ demands strengthen the need for multidisciplinary teams in oncology settings to integrate analgesic care and expertise in CITs to offer personalized management [2].

Conclusions and perspectives

Few clinical trials have been conducted in the different stages of cancer to assess complementary and integrative therapies, and their efficacy is mainly based on professional judgment and patient preferences. CITs should be chosen in adequacy with the ethnocultural and sociological expectancies of patients. Proposing the CIT(s) by the clinicians might prevent patients turning to uncontrolled (pseudo or non) therapies, independent of pain level. Finally, implementation of CITs require an interdisciplinary team to offer optimal patient-centered pain management.

References

Merskey H, Bogduk N (1994) Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the task force on taxonomy of the International Association for the Study of Pain, 2nd ed. IASP Press, Seattle

Syrjala KL, Jensen MP, Mendoza ME, Yi JC, Fisher HM, Keefe FJ (2014) Psychological and behavioral approaches to cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol 32:1703–1711. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.4825

Cassell E (2004) The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M (2010) It’s not over when it’s over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med 40:163–181. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.40.2.c

Institut national du Cancer (INCA) (2012) Synthèse de l’enquête nationale 2010 sur la prise en charge de la douleur chez des patients adultes atteints de cancer. www.e-cancer.fr/content/download/63502/571325/file/ENQDOUL12.pdf. Accessed 17 July 2018

Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, de Conno F, Filbet M, Foubert AJ, Cohen R, Dow L (2009) Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol 20:1420–1433. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp001

Valeberg BT, Rustøen T, Bjordal K et al (2008) Self-reported prevalence, etiology, and characteristics of pain in oncology outpatients. Eur J Pain 12:582–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.09.004

Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, Deandrea S, Bandieri E, Cavuto S, Apolone G (2014) Quality of cancer pain management: an update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:4149–4154. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0383

Breuer B, Chang VT, Von Roenn JH et al (2015) How well do medical oncologists manage chronic cancer pain? A national survey. Oncologist 20:202–209. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0276

Mayor S (2000) Survey of patients shows that cancer pain still undertreated. BMJ 321:1309–1309. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7272.1309/b

MacDonald N, Ayoub J, Farley J, Foucault C, Lesage P, Mayo N (2002) A Quebec survey of issues in cancer pain management. J Pain Symptom Manag 23:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00374-8

Hsieh RK (2005) Pain control in Taiwanese patients with cancer: a multicenter, patient-oriented survey. J Formos Med Assoc 104:913–919

Kasasbeh MAM, McCabe C, Payne S (2017) Cancer-related pain management: a review of knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 26:e12625. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12625

Chow R, Saunders K, Burke H, Belanger A, Chow E (2017) Needs assessment of primary care physicians in the management of chronic pain in cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 25:3505–3514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3774-9

Raphael J, Hester J, Ahmedzai S, Barrie J, Farqhuar-Smith P, Williams J, Urch C, Bennett MI, Robb K, Simpson B, Pittler M, Wider B, Ewer-Smith C, DeCourcy J, Young A, Liossi C, McCullough R, Rajapakse D, Johnson M, Duarte R, Sparkes E (2010) Cancer pain: part 2: physical, interventional and complimentary therapies; management in the community; acute, treatment-related and complex cancer pain: a perspective from the British pain society endorsed by the UK Association of Palliative Medicine and. Pain Med 11:872–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00841.x

Raffa RB, Pergolizzi JV (2014) A modern analgesics pain “pyramid”. J Clin Pharm Ther 39:4–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12110

Chwistek M (2017) Recent advances in understanding and managing cancer pain. F1000Research 6:945. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.10817.1

Candido KD, Kusper TM, Knezevic NN (2017) New cancer pain treatment options. Curr Pain Headache Rep 21(12):12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-017-0613-0

Bennett MI, Eisenberg E, Ahmedzai SH et al (2018) Standards for the management of cancer-related pain across Europe. A position paper from the EFIC task force on cancer pain. Eur J Pain. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1346

Goldstein MS, Brown ER, Ballard-Barbash R et al (2005) The use of complementary and alternative medicine among California adults with and without cancer. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2:557–565. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecam/neh138

Ernst E, Pittler MH, Wider B, Boddy K (2007) Complementary therapies for pain management: an evidence-based approach. Complement Ther pain Manag an evidence-based approach

Ernst E, Pittler MH, Wider B, Boddy K (2008) Oxford handbook of complementary medicine. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Davis EL, Oh B, Butow PN, Mullan BA, Clarke S (2012) Cancer patient disclosure and patient-doctor communication of complementary and alternative medicine use: a systematic review. Oncologist 17:1475–1481. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0223

Ernst E (2010) The public’s enthusiasm for complementary and alternative medicine amounts to a critique of mainstream medicine. Int J Clin Pract 64:1472–1474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02425.x

Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA (2008) Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 112:2577–2592. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23448

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) (2016) Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health#integrative. Accessed 17 July 2018

Van Hecke O, Torrance N, Smith BH (2013) Chronic pain epidemiology—where do lifestyle factors fit in? Br J Pain 7:209–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463713493264

McNeely ML, Parliament M, Courneya KS et al (2004) A pilot study of a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of progressive resistance exercise training on shoulder dysfunction caused by spinal accessory neurapraxia/neurectomy in head and neck cancer survivors. Head Neck 26:518–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20010

McNeely ML, Parliament MB, Seikaly H et al (2008) Effect of exercise on upper extremity pain and dysfunction in head and neck cancer survivors. Cancer 113:214–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23536

Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Robbins KT, Malone J, Seiz A, Koch L, Rao K (2008) Physical activity correlates and barriers in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 16:19–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0293-0

Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W et al (2012) Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 62:242–274. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21142

Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN et al (2007) Physical activity and public health in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39:1435–1445. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616aa2

Brosse AL, Sheets ES, Lett HS, Blumenthal JA (2002) Exercise and the treatment of clinical depression in adults. Sports Med 32:741–760. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200232120-00001

Park C, Malavasi L, Martin P et al (2008) Integrating qi-gong/tai-chi experiences into traditional Western physical activity programs in a long-term care retirement community: 615. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40:S24. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000321549.50666.24

Wolin KY, Schwartz AL, Matthews CE et al (2012) Implementing the exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. J Support Oncol 10:171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suponc.2012.02.001

Bouillet T, Bigard X, Brami C et al (2015) Role of physical activity and sport in oncology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 94:74–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.12.012

Mancuso P (2016) The role of adipokines in chronic inflammation. ImmunoTargets Ther 5:47. https://doi.org/10.2147/ITT.S73223

National Cancer Policy Board (2005) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall, E (eds). The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. http://georgiacore.org/articleImages/articlePDF_396.pdf. Accessed 17 Ju

Santa Mina D, Au D, Brunet J et al (2017) Effects of the community-based wellspring cancer exercise program on functional and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivors. Curr Oncol 24:284–294. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.23.3585

Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, George SM, McTiernan A, Baumgartner KB, Bernstein L, Ballard-Barbash R (2013) Pain in long-term breast cancer survivors: the role of body mass index, physical activity, and sedentary behavior. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137:617–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2335-7

Rajotte EJ, Yi JC, Baker KS et al (2012) Community-based exercise program effectiveness and safety for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 6:219–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-011-0213-7

Knobf MT, Thompson AS, Fennie K, Erdos D (2014) The effect of a community-based exercise intervention on symptoms and quality of life. Cancer Nurs 37:E43–E50. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e318288d40e

Basen-Engquist K, Taylor CLC, Rosenblum C, Smith MA, Shinn EH, Greisinger A, Gregg X, Massey P, Valero V, Rivera E (2006) Randomized pilot test of a lifestyle physical activity intervention for breast cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns 64:225–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2006.02.006

Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Robbins KT et al (2006) Physical activity and quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 14:1012–1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0044-7

Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG et al (2017) Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 67:194–232. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21397

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2017) Massage therapy for health purposes. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/massage/massageintroduction.htm. Accessed 17 July 2018

Jane S-W, Chen S-L, Wilkie DJ et al (2011) Effects of massage on pain, mood status, relaxation, and sleep in Taiwanese patients with metastatic bone pain: a randomized clinical trial. Pain 152:2432–2442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.021

Post-White J, Kinney ME, Savik K, Gau JB, Wilcox C, Lerner I (2003) Therapeutic massage and healing touch improve symptoms in cancer. Integr Cancer Ther 2:332–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735403259064

Corbin L (2005) Safety and efficacy of massage therapy for patients with cancer. Cancer Control 12:158–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/107327480501200303

Fuentes-Márquez P, Cabrera-Martos I, Valenza MC (2018) Physiotherapy interventions for patients with chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1472687

Crawford C, Boyd C, Paat CF, Price A, Xenakis L, Yang EM, Zhang W, the Evidence for Massage Therapy (EMT) Working Group (2016) The impact of massage therapy on function in pain populations—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: part I, patients experiencing pain in the general population. Pain Med 17:1353–1375. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw099

Guo Y, Qiu P, Liu T (2014) Tai Ji Quan: an overview of its history, health benefits, and cultural value. J Sport Health Sci 3:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSHS.2013.10.004

National Cancer Institute. Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2013) Tai chi exercise studied to improve quality of life for senior cancer survivors. https://cam.cancer.gov/cam_at_nci/annual_report/2010/tai_chi_survivors.htm. Accessed

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2017) Mind and body research—information for researchers. https://nccih.nih.gov/grants/mindbody. Accessed 17 July 2018

National Cancer Institute. Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2013) Yoga and Cancer https://cam.cancer.gov/health_information/highlights/yoga_cancer_highlight.htm. Accessed 17 July 2018

National Cancer Institute. Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2016) Research priorities https://cam.cancer.gov/about_us/about_occam.htm#priorities. Accessed 17 July 2018

Buffart LM, van Uffelen JG, Riphagen II et al (2012) Physical and psychosocial benefits of yoga in cancer patients and survivors, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer 12:559. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-559

Carson JW, Carson KM, Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Seewaldt VL (2009) Yoga of awareness program for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results from a randomized trial. Support Care Cancer 17:1301–1309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0587-5

Lou GM, Desai K, Greene L et al (2012) Impact of yoga on functional outcomes in breast cancer survivors with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgias. Integr Cancer Ther 11:313–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735411413270

Yan J-H, Gu W-J, Sun J et al (2013) Efficacy of tai chi on pain, stiffness and function in patients with osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 8:e61672. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061672

Wayne PM, Lee MS, Novakowski J, Osypiuk K, Ligibel J, Carlson LE, Song R (2018) Tai chi and Qigong for cancer-related symptoms and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 12:256–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0665-5

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2016) Tai chi and qi gong: in depth. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/taichi/introduction.htm. Accessed 17 July 2018

Campo RA, O’Connor K, Light KC, Nakamura Y, Lipschitz DL, LaStayo PC, Pappas L, Boucher K, Irwin MR, Agarwal N, Kinney AY (2013) Feasibility and acceptability of a tai chi chih randomized controlled trial in senior female cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther 12:464–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735413485418

Hu C, Zhang H, Wu W, Yu W, Li Y, Bai J, Luo B, Li S (2016) Acupuncture for pain management in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1720239

Bardia A, Barton DL, Prokop LJ et al (2006) Efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine therapies in relieving cancer pain: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 24:5457–5464. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3725

Chiu HY, Hsieh YJ, Tsai PS (2017) Systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture to reduce cancer-related pain. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 26:e12457. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12457

Bao T, Cai L, Giles JT, Gould J, Tarpinian K, Betts K, Medeiros M, Jeter S, Tait N, Chumsri S, Armstrong DK, Tan M, Folkerd E, Dowsett M, Singh H, Tkaczuk K, Stearns V (2013) A dual-center randomized controlled double blind trial assessing the effect of acupuncture in reducing musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer patients taking aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 138:167–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2427-z

Crew KD, Capodice JL, Greenlee H, Brafman L, Fuentes D, Awad D, Yann Tsai W, Hershman DL (2010) Randomized, blinded, sham-controlled trial of acupuncture for the management of aromatase inhibitor-associated joint symptoms in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:1154–1160. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4708

Oh B, Kimble B, Costa DSJ, Davis E, McLean A, Orme K, Beith J (2013) Acupuncture for treatment of arthralgia secondary to aromatase inhibitor therapy in women with early breast cancer: pilot study. Acupunct Med 31:264–271. https://doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2012-010309

Mao JJ, Xie SX, Farrar JT, Stricker CT, Bowman MA, Bruner D, DeMichele A (2014) A randomised trial of electro-acupuncture for arthralgia related to aromatase inhibitor use. Eur J Cancer 50:267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.022

Paley CA, Johnson MI, Tashani OA, Bagnall A-M (2015) Acupuncture for cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD007753. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007753.pub3

Robb KA, Newham DJ, Williams JE (2007) Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation vs. transcutaneous spinal electroanalgesia for chronic pain associated with breast cancer treatments. J Pain Symptom Manag 33:410–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.020

Hurlow A, Bennett MI, Robb KA, et al (2012) Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD006276. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006276.pub3

Moon JY, Kurihara C, Beckles JP, Williams KE, Jamison DE, Cohen SP (2015) Predictive factors associated with success and failure for Calmare (scrambler) therapy. Clin J Pain 31:750–756. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000155

Lee SC, Park KS, Moon JY, Kim EJ, Kim YC, Seo H, Sung JK, Lee DJ (2016) An exploratory study on the effectiveness of “Calmare therapy” in patients with cancer-related neuropathic pain: a pilot study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 21:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2015.12.001

Notaro P, Dell’Agnola CA, Dell’Agnola AJ, Amatu A, Bencardino KB, Siena S (2016) Pilot evaluation of scrambler therapy for pain induced by bone and visceral metastases and refractory to standard therapies. Support Care Cancer 24:1649–1654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2952-x

Reyes-Gibby CC, Anderson KO, Morrow PK et al (2012) Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Women’s Health 21:311–318. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.2852

Strada EA, Portenoy RK (2017) Psychological, rehabilitative, and integrative therapies for cancer pain. Uptodate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/psychological-rehabilitative-and-integrative-therapies-for-cancer-pain#H44713544. Accessed 17 July 2018

Mustafa M, Carson-Stevens A, Gillespie D, Edwards AG (2013) Psychological interventions for women with metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD004253. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004253.pub4

Lee R (1999) Guided imagery as supportive therapy in cancer treatment. Altern Med 2:61–64

Roffe L, Schmidt K, Ernst E (2005) A systematic review of guided imagery as an adjuvant cancer therapy. Psychooncology 14:607–617. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.889

Sheinfeld Gorin S, Krebs P, Badr H et al (2012) Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions to reduce pain in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:539–547. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0437

Johannsen M, Farver I, Beck N, Zachariae R (2013) The efficacy of psychosocial intervention for pain in breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 138:675–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2503-4

Wint SS, Eshelman D, Steele J, Guzzetta CE (2002) Effects of distraction using virtual reality glasses during lumbar punctures in adolescents with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 29:E8–E15. https://doi.org/10.1188/02.ONF.E8-E15

Schneider SM, Workman ML Virtual reality as a distraction intervention for older children receiving chemotherapy. Pediatr Nurs 26:593–597

Gershon J, Zimand E, Pickering M, Rothbaum BO, Hodges L (2004) A pilot and feasibility study of virtual reality as a distraction for children with cancer. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43:1243–1249. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000135621.23145.05

Chirico A, Lucidi F, De Laurentiis M et al (2016) Virtual reality in health system: beyond entertainment. A mini-review on the efficacy of VR during cancer treatment. J Cell Physiol 231:275–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.25117

Indovina P, Barone D, Gallo L et al (2018) Virtual reality as a distraction intervention to relieve pain and distress during medical procedures. Clin J Pain 34:1. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000599

House G, Burdea G, Grampurohit N, Polistico K, Roll D, Damiani F, Hundal J, Demesmin D (2016) A feasibility study to determine the benefits of upper extremity virtual rehabilitation therapy for coping with chronic pain post-cancer surgery. Br J Pain 10:186–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463716664370

Tashjian VC, Mosadeghi S, Howard AR, Lopez M, Dupuy T, Reid M, Martinez B, Ahmed S, Dailey F, Robbins K, Rosen B, Fuller G, Danovitch I, IsHak W, Spiegel B (2017) Virtual reality for management of pain in hospitalized patients: results of a controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 4:e9. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.7387

Li A, Montaño Z, Chen VJ, Gold JI (2011) Virtual reality and pain management: current trends and future directions. Pain Manag 1:147–157. https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt.10.15

Kwekkeboom KL, Cherwin CH, Lee JW, Wanta B (2010) Mind-body treatments for the pain-fatigue-sleep disturbance symptom cluster in persons with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag 39:126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.022

Mendoza ME, Capafons A, Gralow JR et al (2017) Randomized controlled trial of the Valencia model of waking hypnosis plus CBT for pain, fatigue, and sleep management in patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Psychooncology 26:1832–1838. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4232

Institut National du Cancer (2016) Axes opportuns d’évolution du panier de soins oncologiques de support. http://www.e-cancer.fr/Expertises-et-publications/Catalogue-des-publications/Axes-opportuns-d-evolution-du-panier-des-soins-oncologiques-de-support-R

Butler LD, Koopman C, Neri E, Giese-Davis J, Palesh O, Thorne-Yocam KA, Dimiceli S, Chen XH, Fobair P, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D (2009) Effects of supportive-expressive group therapy on pain in women with metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychol 28:579–587. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016124

Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M et al (2001) The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 345:1719–1726. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011871

Spiegel D, Bloom JR (1983) Group therapy and hypnosis reduce metastatic breast carcinoma pain. Psychosom Med 45:333–339

Binns-Turner PG, Wilson LL, Pryor ER, Boyd GL, Prickett CA (2011) Perioperative music and its effects on anxiety, hemodynamics, and pain in women undergoing mastectomy. AANA J 79:S21–S27

Li X-M, Zhou K-N, Yan H et al (2012) Effects of music therapy on anxiety of patients with breast cancer after radical mastectomy: a randomized clinical trial. J Adv Nurs 68:1145–1155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05824.x

Wang Y, Tang H, Guo Q et al (2015) Effects of intravenous patient-controlled sufentanil analgesia and music therapy on pain and hemodynamics after surgery for lung cancer: a randomized parallel study. J Altern Complement Med 21:667–672. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2014.0310

Bradt J, Dileo C, Magill L, Teague A (2016) Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD006911. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006911.pub3

Lee JH (2016) The effects of music on pain: a meta-analysis. J Music Ther 53:430–477. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thw012

Gunnarsdottir S, Sigurdardottir V, Kloke M et al (2017) A multicenter study of attitudinal barriers to cancer pain management. Support Care Cancer 25:3595–3602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3791-8

Valeberg BT, Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Rustøen T (2016) Comparison of oncology patients’ and their family caregivers’ attitudes and concerns toward pain and pain management. Cancer Nurs 39:328–334. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000319

Peacock S, Patel S (2008) Cultural influences on pain. Rev Pain 1:6–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/204946370800100203

Bosch F, Baños JE (2002) Religious beliefs of patients and caregivers as a barrier to the pharmacologic control of cancer pain*. Clin Pharmacol Ther 72:107–111. https://doi.org/10.1067/mcp.2002.126180

Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA et al (2003) The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 4:277–294

Chen CH, Tang ST, Chen CH (2012) Meta-analysis of cultural differences in Western and Asian patient-perceived barriers to managing cancer pain. Palliat Med 26:206–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311402711

Edwards RR, Moric M, Husfeldt B et al (2005) Ethnic similarities and differences in the chronic pain experience: a comparison of African American, Hispanic, and White patients. Pain Med 6:88–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05007.x

Grant JA, Courtemanche J, Rainville P (2011) A non-elaborative mental stance and decoupling of executive and pain-related cortices predicts low pain sensitivity in zen meditators. Pain 152:150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.006

Baer RA (2006) Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 10:125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg015

Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H (2004) Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. J Psychosom Res 57:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7

Turner JA, Anderson ML, Balderson BH, Cook AJ, Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC (2016) Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain 157:2434–2444. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000635

Rosenzweig S, Greeson JM, Reibel DK, Green JS, Jasser SA, Beasley D (2010) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain conditions: variation in treatment outcomes and role of home meditation practice. J Psychosom Res 68:29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.03.010

Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, Colaiaco B, Maher AR, Shanman RM, Sorbero ME, Maglione MA (2017) Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med 51:199–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2

Ball EF, Nur Shafina Muhammad Sharizan E, Franklin G, Rogozińska E (2017) Does mindfulness meditation improve chronic pain? A systematic review. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 29:1. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0000000000000417

Satija A, Bhatnagar S (2017) Complementary therapies for symptom management in cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care 23:468–479. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_100_17

Lee CE, Kim S, Kim S et al (2017) Effects of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program on the physical and psychological status and quality of life in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Holist Nurs Pract 31:260–269. https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0000000000000220

Luebbert K, Dahme B, Hasenbring M (2001) The effectiveness of relaxation training in reducing treatment-related symptoms and improving emotional adjustment in acute non-surgical cancer treatment: a meta-analytical review. Psychooncology 10:490–502

Roth AD, Pilling S (2008) Using an evidence-based methodology to identify the competences required to deliver effective cognitive and behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety disorders. Behav Cogn Psychother 36:129–147. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465808004141

McCracken LM, Vowles KE (2014) Acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness for chronic pain: model, process, and progress. Am Psychol 69:178–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035623

The British Pain Society (ed) (2017) Recommended guidelines for pain management programmes for adults. The British Pain Society (ed), London

Hunot V, Moore TH, Caldwell D, et al (2010) Mindfulness-based “third wave” cognitive and behavioural therapies versus other psychological therapies for depression. In: Churchill R (ed) Cochrane database of systematic reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester

Carver CS, Smith RG, Antoni MH, Petronis VM, Weiss S, Derhagopian RP (2005) Optimistic personality and psychosocial well-being during treatment predict psychosocial well-being among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Health Psychol 24:508–516. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.508

Phillips KM, Antoni MH, Carver CS, Lechner SC, Penedo FJ, McCullough ME, Gluck S, Derhagopian RP, Blomberg BB (2011) Stress management skills and reductions in serum cortisol across the year after surgery for non-metastatic breast cancer. Cogn Ther Res 35:595–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9398-3

Bennett MI, Bagnall A-M, Closs JS (2009) How effective are patient-based educational interventions in the management of cancer pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 143:192–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.016

Tatrow K, Montgomery GH (2006) Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques for distress and pain in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med 29:17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-005-9036-1

Devine EC (2003) Meta-analysis of the effect of psychoeducational interventions on pain in adults with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 30:75–89. https://doi.org/10.1188/03.ONF.75-89

Johannsen M, O’Connor M, O’Toole MS et al (2016) Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on late post-treatment pain in women treated for primary breast Cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 34:3390–3399. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.65.0770

Johannsen M, O’Connor M, O’Toole MS, Jensen AB, Zachariae R (2017) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and persistent pain in women treated for primary breast cancer. Clin J Pain 34:1. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000510

Robb KA, Williams JE, Duvivier V, Newham DJ (2006) A pain management program for chronic cancer-treatment-related pain: a preliminary study. J Pain 7:82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2005.08.007

Gilpin HR, Keyes A, Stahl DR, Greig R, McCracken LM (2017) Predictors of treatment outcome in contextual cognitive and behavioral therapies for chronic pain: a systematic review. J Pain 18:1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.04.003

Davis MC, Zautra AJ (2013) An online mindfulness intervention targeting socioemotional regulation in fibromyalgia: results of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 46:273–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9513-7

Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Wolf LD et al (2015) Mindfulness and cognitive–behavioral interventions for chronic pain: differential effects on daily pain reactivity and stress reactivity. J Consult Clin Psychol 83:24–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038200

Zautra AJ, Davis MC, Reich JW et al (2008) Comparison of cognitive behavioral and mindfulness meditation interventions on adaptation to rheumatoid arthritis for patients with and without history of recurrent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 76:408–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.408

Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Lamers SMA, Schreurs KMG (2016) Positive psychological wellbeing is required for online self-help acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain to be effective. Front Psychol 7:353. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00353

Wetherell JL, Petkus AJ, Alonso-Fernandez M et al (2016) Age moderates response to acceptance and commitment therapy vs. cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 31:302–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4330

Garssen B, Boomsma MF, de Jager Meezenbroek E et al (2013) Stress management training for breast cancer surgery patients. Psychooncology 22:572–580. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3034

Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, Fiscella K, Hoerger M, Tancredi DJ, Xing G, Gramling R, Mohile S, Franks P, Kaesberg P, Plumb S, Cipri CS, Street RL Jr, Shields CG, Back AL, Butow P, Walczak A, Tattersall M, Venuti A, Sullivan P, Robinson M, Hoh B, Lewis L, Kravitz RL (2016) Effect of a patient-centered communication intervention on oncologist-patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 3:92–100. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4373

Oldenmenger WH, Sillevis Smitt PAE, van Montfort CAGM et al (2011) A combined pain consultation and pain education program decreases average and current pain and decreases interference in daily life by pain in oncology outpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Pain 152:2632–2639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.009

Kravitz RL, Tancredi DJ, Jerant A, Saito N, Street RL, Grennan T, Franks P (2012) Influence of patient coaching on analgesic treatment adjustment: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manag 43:874–884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.020

Howell D, Harth T, Brown J, Bennett C, Boyko S (2017) Self-management education interventions for patients with cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 25:1323–1355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3500-z

Rustøen T, Valeberg BT, Kolstad E, Wist E, Paul S, Miaskowski C (2014) A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of a self-care intervention to improve Cancer pain management. Cancer Nurs 37:34–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182948418

Jahn P, Kuss O, Schmidt H et al (2014) Improvement of pain-related self-management for cancer patients through a modular transitional nursing intervention: a cluster-randomized multicenter trial. Pain 155:746–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.006

Adam R, Burton CD, Bond CM, de Bruin M, Murchie P (2017) Can patient-reported measurements of pain be used to improve cancer pain management? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 7:00.1–00.0000. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001137

Wilkie D, Berry D, Cain K et al (2010) Effects of coaching patients with lung cancer to report cancer pain. West J Nurs Res 32:23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945909348009

Cleeland CS, Wang XS, Shi Q et al (2011) Automated symptom alerts reduce postoperative symptom severity after cancer surgery: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 29:994–1000. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.29.8315

Manzano A, Ziegler L, Bennett M (2014) Exploring interference from analgesia in patients with cancer pain: a longitudinal qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 23:1877–1888

Street RL, Tancredi DJ, Slee C et al (2014) A pathway linking patient participation in cancer consultations to pain control. Psychooncology 23:1111–1117. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3518

Fulcrand J, Delvoye J, Boursier A, Evrard M, Dujardin L, Ferret L, Barrascout E, Lemaire A (2018) Place du pharmacien clinicien dans la prise en charge des patients en soins palliatifs. J Pain Symptom Manag 56:e101–e102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.343

Kroenke K, Theobald D, Wu J, Norton K, Morrison G, Carpenter J, Tu W (2010) Effect of telecare management on pain and depression in patients with cancer. JAMA 304:163–171. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.944

Adam R, de Bruin M, Burton CD, Bond CM, Giatsi Clausen M, Murchie P (2018) What are the current challenges of managing cancer pain and could digital technologies help? BMJ Support Palliat Care 8:204–212. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001232

Kwon JH (2014) Overcoming barriers in cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol 32:1727–1733. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4827

Kasasbeh MAM, McCabe C, Payne S (2017) Action learning: an effective way to improve cancer-related pain management. J Clin Nurs 26:3430–3441. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13709

Physical Activities Guidelines Advisory Committee (2008) Physical activity guidelines advisory committee report. US Department of Health and Human Services (ed), Washington DC

Buffart LM, Galvão DA, Brug J et al (2014) Evidence-based physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors: current guidelines, knowledge gaps and future research directions. Cancer Treat Rev 40:327–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.06.007

Campbell KL, Neil SE, Winters-Stone KM (2012) Review of exercise studies in breast cancer survivors: attention to principles of exercise training. Br J Sports Med 46:909–916. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2010-082719

Sundaramurthi T, Gallagher N, Sterling B (2017) Cancer-related acute pain: a systematic review of evidence-based interventions for putting evidence into practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 21:13–30

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by Xavier Amores, M.D. and Viorica Braniste, M.D. and Ph.D. (Kyowa Kirin), and Robert Campos Oriola, Ph.D, and Marie-Odile Barbaza, MD, (Auxesia) for manuscript preparation.

Funding

This article was funded by Kyowa Kirin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Caroline Maindet reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Mundipharma; and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, Grunenthal, Hospira, Takeda, and Janssen Cilag, outside the submitted work. Alexis Burnod reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, outside the submitted work. Christian Minello reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Takeda; and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, Mundi Pharma, Mylan Pharma, and Grunenthal, outside the submitted work. Brigitte George reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Mundipharma, non-financial support from Grunenthal and Kyowa Kirin, outside the submitted work; participation to a clinical study without honoraria from Bouchara. Gilles Allano reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Grunenthal, Mundipharma, and Medtronic; and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin, outside the submitted work. Antoine Lemaire reports non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin France, during the conduct of the submitted work; personal fees and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin International, Mundi Pharma, Grunenthal, and Takeda; personal fees from Mylan; and non-financial support from Kyowa Kirin France, Archimèdes Pharma, Teva, Prostrakan, outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maindet, C., Burnod, A., Minello, C. et al. Strategies of complementary and integrative therapies in cancer-related pain—attaining exhaustive cancer pain management. Support Care Cancer 27, 3119–3132 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04829-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04829-7