Abstract

Purpose

This multicenter phase II trial assessed the clinical benefit of a multidisciplinary oral care program in reducing the incidence of severe chemoradiotherapy-induced oral mucositis (OM).

Methods

Patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) who were scheduled to receive definitive or postoperative chemoradiotherapy were enrolled. The oral care program included routine oral screening by dentists and a leaflet containing instructions regarding oral care, nutrition, and lifestyle. Oral hygiene and oral care were evaluated continuously during and after the course of chemoradiotherapy. The primary endpoint was the incidence of grade ≥3 OM assessed by certified medical staff according to the Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events version 3.0.

Results

From April 2012 to December 2013, 120 patients with HNC were enrolled. Sixty-four patients (53.3 %) developed grade ≥3 OM (i.e., functional/symptomatic). The incidence of grade ≤1 OM at 2 and 4 weeks after radiotherapy completion was 34.2 and 67.6 %, respectively. Clinical examination revealed that 51 patients (42.5 %) developed grade ≥3 OM during chemoradiotherapy. The incidence of grade ≤1 OM at 2 and 4 weeks after radiotherapy completion was 54.7 and 89.2 %, respectively. The incidences of grade 3 infection and pneumonitis throughout chemoradiotherapy were <5 %. Only 6.7 % of patients had unplanned breaks in radiotherapy, and 99.2 % completed treatment.

Conclusions

A systematic oral care program alone is insufficient to decrease the incidence of severe OM in patients with HNC being treated with chemoradiotherapy. However, systematic oral care programs may indirectly improve treatment compliance by decreasing infection risk.

Trial registration number: UMIN000006660

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Head and neck cancers (HNCs) primarily involve the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. Most patients with HNC have locally or regionally advanced disease at the time of diagnosis [1]. Several recent randomized phase III studies support the use of radiotherapy and concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy as a standard treatment for HNC [2, 3].

Oral mucositis (OM) is one of the important adverse events of radiotherapy and concomitant chemoradiotherapy, and worsens the quality of life of patients with HNC [4]. The incidence of OM is high in these patients, ranging from 50 to 90 % depending on radiotherapy field, dose, fractionation, and chemotherapy administration [5]. An increase in severe (i.e., grade 3–4) OM will cause substantial pain and subsequently interfere with the patients’ ability to chew and swallow, possibly leading to malnutrition. Irradiation damages the salivary glands, which causes dry mouth and facilitates bacterial proliferation inside the oral cavity. Furthermore, chemotherapeutic agents can induce myelosuppression and aggravate OM. These factors collectively increase patient susceptibility not only to oral infection but also to aspiration pneumonitis. Treatment interruptions and dose reductions due to OM may ultimately affect therapeutic outcomes including cure rates, durability of remission, and patient survival [6–8]. Therefore, strategies to prevent severe OM are required.

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of oral care during chemotherapy [9–11]. However, there is no systematic multidisciplinary oral care protocol for patients with HNC during chemoradiotherapy treatment. Therefore, this multicenter phase II study evaluated whether a multidisciplinary oral care program for the systematic management of OM can reduce the incidence of severe OM in patients with HNC undergoing chemoradiotherapy.

Patients and methods

Eligibility

The enrollment criteria were age 20–75 years; ECOG performance status 0–1; adequate hematological, liver, and renal function; scheduled receipt of definitive or postoperative chemoradiotherapy with platinum-based chemotherapy; scheduled receipt of >50 Gy irradiation to the oral space; sufficient eating ability; normalcy of diet evaluated with the Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck cancer patients (PSSHN) ≥50 [12]; ability to keep water inside the oral cavity; and absence of OM according to the Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of Shizuoka Cancer Center (Shizuoka, Japan), Aichi Cancer Center (Nagoya, Japan), and the National Cancer Center Hospital East (Chiba, Japan), and met the standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent to treatment was obtained from all patients before treatment initiation. This trial is registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000006660).

Oral care program

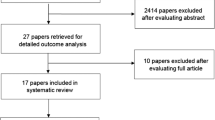

The oral care program was executed from initiation to 1 month after termination of chemoradiotherapy (Fig. 1). The intervention provided by the multidisciplinary oral care team was as follows. Before chemoradiotherapy, patients received routine oral screening by dentists to determine the status of teeth, periodontal tissue, and oral hygiene. Any required dental treatment was performed. Patients were informed about adverse oral reactions caused by chemoradiotherapy and given a leaflet containing instructions about tooth brushing, mouth washing, nutrition, and lifestyle. Patients were encouraged to undergo percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) before starting chemoradiotherapy.

All patients were told to see the dentist weekly for assessment of the status of the oral cavity. Instructions regarding oral hygiene and oral care were given at least weekly to patients throughout the course of chemoradiotherapy. If necessary, professional oral health care including mechanical tooth cleaning was provided. OM severity was evaluated at least three times/week by physicians, dentists, dental hygienists, pharmacists, or nurses according to the CTCAE version 3.0 (see “Oral assessment”). Patients’ self-reported physical status including body weight, temperature, use of opioids, oral intake, and mouth washing were collected on daily self-assessment sheets, which were reviewed by the multidisciplinary oral care team who provided feedback to the patient at least weekly. All pain control was performed according to our opioid-based pain control (OBPC) program [13] (Supplementary Material 1). Patients unable to eat adequately or hydrate orally started nutritional support by PEG as necessary.

Patients were observed periodically by the medical staff at least weekly in the first month after chemoradiotherapy termination. Patients who were treated on an inpatient basis during chemoradiotherapy were also carefully followed up in outpatient wards. Oral care and OM assessment were performed and documented continuously by medical staff. Furthermore, patients’ self-care and self-assessments were assessed by medical staff. Nutritional support by PEG was performed depending on oral intake ability. Dentists continued to follow-up patients to identify cases of radiotherapy-related late toxicity, such as osteoradionecrosis, up to 1 year after completion of chemoradiotherapy.

Oral assessment

OM severity was assessed with respect to functional disorders and symptomatic aspects as well as clinical examination according to the CTCAE version 3.0. Medical staff involved in OM evaluation underwent specific training and testing to minimize interobserver variation and familiarize the staff with the OM measurement scales (Supplementary Material 2).

After training on OM grading, medical staff members who scored >80 % on the final examination were certified. Certified staff members observed the mucosa of the lips, bilateral buccal mucosae, bilateral lateral tongue borders, buccal floor, and ventral tongue at least three times/week, and the worst grade was recorded in the oral care assessment sheet. Submission of photo-documentation to the medical record was encouraged. Discordant assessments were resolved by the majority opinion.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint was the incidence of grade 3–4 OM according to the CTCAE version 3.0 (clinical exam and functional/symptomatic) elapsed from chemoradiotherapy initiation to 1 month after the completion of radiotherapy. In our previous study of the OBPC program, the incidences of grade ≥3 OM (clinical exam) and grade ≥3 OM (functional/symptomatic) were 52.9 and 59.8 %, respectively [13]. Therefore, our oral care program was to be considered successful if it reduced the incidence of grade 3–4 OM to ≤38 %, and unworthy of additional study if the incidence was ≥50 %. With 80 % power and a one-sided type 1 error of 5 %, the minimum number of patients required to evaluate the primary endpoint was 107. Assuming a 10 % drop-out rate, we calculated a required total sample size of 120 patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 120 patients from three institutions were registered between April 2012 and December 2013. Their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Among them, 102 (85.0 %) and 18 (15.0 %) underwent definitive chemoradiotherapy and postoperative chemoradiotherapy, respectively. The median radiation dose was 70 Gy (range 60–70), and the most common chemotherapy regimen was cisplatin alone (116/120, 96.7 %). Almost all patients (112/120, 93.3 %) had a PSSHN score of 100, indicating appropriate eating and swallowing abilities before chemoradiotherapy initiation.

OM assessed by clinical examination

Clinical examinations found that 51 patients (42.5 %) developed grade 3 OM during chemoradiotherapy; no patients had grade 4 OM (Table 2). The median duration between grade 3 OM (clinical exam) onset and recovery to grade 2 OM was 21.0 days (4.0–66.0 days). The incidence of grade ≤1 OM at 2 and 4 weeks after radiotherapy completion was 54.7 and 89.2 %, respectively; meanwhile, only 12.0 and 0.9 % of patients still had grade 3 OM at these times, respectively (Table 3).

OM (functional/symptomatic) and nutritional intervention

Sixty-three patients (52.5 %) developed grade 3 OM (functional/symptomatic) and one (0.8 %) developed grade 4 OM. Thus, the incidence of grade ≥3 OM was 53.3 %. However, 70 patients (58.3 %) were unable to obtain adequate nutrition via oral intake; 14 of them were unable to obtain sufficient nutrition via oral intake despite less than grade 2 OM (functional/symptomatic) because of diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, a taste disorder, PEG complications, loss of appetite, aspiration pneumonia prevention tactics, general fatigue, or pharyngitis. Among the patients unable to adequately eat or hydrate orally, the median onset of nutritional support was 32.5 days (Table 4). The median duration between grade 3 OM (functional/symptomatic) onset and recovery to grade ≤2 OM was 32.0 days (3.0–93.0 days). Furthermore, the incidence of grade ≤1 OM at 2 and 4 weeks after radiotherapy completion was 34.2 and 67.6 %, respectively; meanwhile, 24.8 and 6.3 % of patients, respectively, still had grade 3 OM at these times (Table 3). Overall, 88 patients (73.3 %) used PEG or a nasal tube for nutritional support during treatment not only due to OM but also for other conditions, such as a taste disorder, dysphagia, or a dry mouth. However, 1 year after radiotherapy completion, 96 patients (80 %) were able to adequately eat and hydrate orally without nutritional support (Table 4). The main reasons for inability to obtain adequate nutrition via oral intake after completion of treatment were dry mouth and dysgeusia.

Other toxicities

The toxicity profiles during and after chemoradiotherapy are shown in Table 2. Mucositis, dermatitis, and dry mouth were the most common acute toxicities. From chemoradiotherapy initiation to 1 month after radiotherapy completion, 56 (46.7 %) and 3 (2.5 %) patients exhibited grades 2 and 3 weight loss, respectively. Grade 3 infection and febrile neutropenia occurred in 1 (0.8 %) and 3 (2.5 %) patients, respectively. Five patients developed grade 3 pneumonitis. One patient with oropharyngeal cancer died 5 days after radiotherapy completion because of tumor bleeding. Only 1 patient (0.8 %) experienced grade 2 post-radiation jaw osteonecrosis, although 15 patients (12.5 %) were not followed up the full 1 year after radiotherapy completion because of death or relocation.

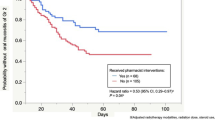

Treatment compliance

Radiotherapy was completed in 99.2 % of patients (119/120). One patient was scheduled for 70 Gy radiation, but this was halted at 60 Gy because of grade 4 mucositis. Eight patients (6.7 %) had an unplanned break in radiotherapy because of aspiration pneumonitis in 2, influenza in 1, fatigue in 1, abdominal pain in 1, unplanned machine trouble in 1, difficulty in holding a dorsal position due to headache in 1, and grade 4 thrombocytopenia in 1; there were no therapy breaks due to mucositis. Dose reduction of concurrent chemotherapy was required in 43 patients (35.8 %) but it was not due to mucositis. Planned administration of chemotherapeutic agents was postponed in 42 patients (35.0 %), but only 1 patient (2.4 %) required postponement because of mucositis.

Discussion

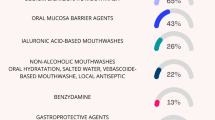

Basic oral care is considered common sense in the management of radiation-induced mucositis. The MASCC and NCCN guidelines and a National Cancer Institute report recommend basic oral care as a standard practice to prevent infections and help alleviate mucosal symptoms [14, 15]. However, there is little direct evidence that oral care significantly affects the incidence or severity of chemoradiotherapy-induced OM.

This study is the first prospective trial investigating the efficacy of the multidisciplinary oral care program for the prevention of chemoradiotherapy-induced severe OM in patients with HNC. Because there was no systematic oral care program in our previous OBPC program, the patients did not see dentists for oral care. The oral care program encompasses a self-care program to enhance patients’ self-care abilities including (i) providing educational information on OM and oral care, (ii) self-assessment, and (iii) continuous supportive interactions with medical staff throughout chemoradiotherapy (Fig. 1). Although we expected the oral care program would reduce the incidence of chemoradiotherapy-induced mucositis, the results revealed that grade ≥3 OM (functional/symptomatic) occurred in more than half of the patients. Clinical examinations revealed that 42.5 % of patients developed grade 3 mucositis, which was more than what was predicted by our a priori hypothesis (38 %). Although the incidence of mucositis in the present study is less than that in our previous phase II study of the OBPC program, these results suggest statistical negativity; i.e., a systematic oral care program alone is insufficient to decrease the incidence of chemoradiotherapy-induced severe OM in HNC patients.

Several factors may explain this negative result. The first point is the choice of statistical threshold; we expected the oral care program to reduce the incidence of grade 3–4 OM by 12 %. However, this expectation might have been too high. Furthermore, we used the incidence of grade ≥3 OM assessed by the CTCAE 3.0 as an objective primary study endpoint. However, OM assessed by the CTCAE 3.0 comprises a combination of an examination, and functional and symptomatic aspects, which makes it difficult to statistically interpret the significance of oral care. Therefore, in hindsight, we should have chosen either grade ≥3 OM (functional/symptomatic) or grade ≥3 OM (clinical exam) as the primary endpoint. Second, nutritional support might have been insufficient. Several studies suggest early nutritional intervention prevents body weight loss and subsequently improves treatment outcomes in patients with HNC undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy [16, 17]. However, in the present study, 46.7 % of patients exhibited body weight loss >10 % from chemoradiotherapy initiation to 1 month after radiotherapy completion. Therefore, adequate nutritional support might have helped maintain body weight and subsequently diminished the risk of severe OM. Third, it is impossible to control mucositis within the pharyngeal space by oral care alone, and pharyngeal mucositis can cause difficulty in oral intake. To control for this factor, both oral cavity and pharyngeal mucosa should have been assessed. Finally, we were not able to control for fungal infections in this study, although the prevalence of oral candidiasis during head and neck radiation therapy is greater than 30 % [18]. Chemoradiotherapy for HNCs results in salivary hypofunction and local tissue damage, which is associated with a significantly increased risk for oral fungal infection. Therefore, it is possible that oral fungal infection may increase oral burning pains and taste changes, and may have a significant impact on quality of life. In future studies, early recognition and treatment of oral candidiasis may contribute to reducing the risk of OM. The prophylactic use of anti-fungal agents or a salivary gland function-preserving agent may help to prevent severe OM.

Nonetheless, this study produced several interesting results. The rates of grade 3 infection and pneumonitis throughout chemoradiotherapy were <5 %. Concordant with this toxicity profile, the rate of unplanned breaks in radiotherapy was only 6.7 %, and the treatment completion rate was 99.2 %. Thus, there was improvement in treatment compliance compared to our phase II study of the OBPC program. These results suggest that systematic oral care programs may indirectly improve treatment compliance through decreasing infection risk.

Four weeks after radiotherapy completion, 89.2 and 67.6 % of patients presented with grade ≤1 OM (clinical exam) and grade ≤1 OM (functional/symptomatic), respectively. Furthermore, 80 % of patients were able to adequately eat and hydrate orally without nutritional support 1 year after radiotherapy completion. Meanwhile, in our previous retrospective study, the median duration of nutritional support was 395 days in patients with oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers and 37 % of patients required nutritional support for more than 1 year [19]. Therefore, our oral care program may shorten the duration of severe OM in the acute phase and subsequently enable patients to receive enough calories orally without nutritional support sooner.

Late radiation-induced tissue injuries occur in some patients and develop months to years following radiotherapy. Osteoradionecrosis sometimes causes severe pain and pathologic fracture of the mandible, severely impairs quality of life, and is often refractory to treatment. Its incidence varies greatly from 1 to 37.5 % [20, 21]. Post-treatment follow-up showed only one patient in our study experienced grade 2 osteonecrosis of the jaw after radiotherapy completion, although the follow-up duration was only 1 year and not all cases could be followed. Osteoradionecrosis is partially associated with poor oral hygiene [22, 23]. Therefore, our findings suggest the maintenance of oral hygiene during and after radiotherapy might decrease the risk of late dental complications including osteoradionecrosis.

The primary limitation of our study is that it is not a randomized trial, although we used our previous phase II study of the OBPC program as a historical group for comparison. Furthermore, no subjective toxicity measurements reported by patients were included in the analysis.

In conclusion, a systematic oral care program alone is insufficient to decrease the incidence of severe OM in patients with HNC undergoing chemoradiotherapy. However, the benefits of oral care should not be overlooked; it can aid recovery from acute toxicity, help reduce long-term nutritional consequences, and prevent late toxicity. Therefore, our results corroborate the recommendations to institute comprehensive oral care for patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy. In the future, the individualization of oral care programs may be necessary, taking comorbidities, such as diabetes, drinking, smoking, and age into consideration. Furthermore, multidisciplinary strategies based on the systematic oral care and OBPC program, including additional nutritional management and development of mouth washing agents, are required to reduce the burden of OM.

References

Marur S, Forastiere AA (2008) Head and neck cancer: changing epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 83:489–501

Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. (2003) Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 349:2091–2098

Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, et al. (2003) An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 21:92–98

Vera-Llonch M, Oster G, Hagiwara M, Sonis S (2006) Oral mucositis in patients undergoing radiation treatment for head and neck carcinoma. Cancer 106:329–336

Elting LS, Cooksley CD, Chambers MS, Garden AS (2007) Risk, outcomes, and costs of radiation-induced oral mucositis among patients with head-and-neck malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 68:1110–1120

Hansen O, Overgaard J, Hansen HS, Overgaard M, Höyer M, Jörgensen KE (1997) Importance of overall treatment time for the outcome of radiotherapy of advanced head and neck carcinoma: dependency on tumor differentiation. Radiother Oncol 43:47–51

Russo G, Haddad R, Posner M, Machtay M (2008) Radiation treatment breaks and ulcerative mucositis in head and neck cancer. Oncologist 13:886–898

Bese NS, Hendry J, Jeremic B (2007) Effects of prolongation of overall treatment time due to unplanned interruptions during radiotherapy of different tumor sites and practical methods for compensation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 68:654–661

Larson PJ, Miaskowski C, MacPhail L, et al. (1998) The PRO-SELF Mouth Aware program: an effective approach for reducing chemotherapy-induced mucositis. Cancer Nurs 21:263–268

Cheng KK, Molassiotis A, Chang AM, Wai WC, Cheung SS (2001) Evaluation of an oral care protocol intervention in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in paediatric cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 37:2056–2063

Saito H, Watanabe Y, Sato K, et al. (2014) Effects of professional oral health care on reducing the risk of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Support Care Cancer 22:2935–2940

List MA, Ritter-Sterr C, Lansky SB (1990) A performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer 66:564–569

Zenda S, Matsuura K, Tachibana H, et al. (2011) Multicenter phase II study of an opioid-based pain control program for head and neck cancer patients receiving chemoradiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 101:410–414

Bensinger W, Schubert M, Ang KK, et al. (2008) NCCN Task Force report: prevention and management of mucositis in cancer care. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 6(Suppl 1):S1–S21

Rosenthal DI, Trotti A (2009) Strategies for managing radiation-induced mucositis in head and neck cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol 19:29–34

Garg S, Yoo J, Winquist E (2010) Nutritional support for head and neck cancer patients receiving radiotherapy: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 18:667–677

Paccagnella A, Morello M, Da Mosto MC, et al. (2010) Early nutritional intervention improves treatment tolerance and outcomes in head and neck cancer patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Support Care Cancer 18:837–845

RV L, MC L, CH H, Ariyawardana A, D'Amato-Palumbo S, Fischer DJ, Martof A, Nicolatou-Galitis O, Patton LL, Elting LS, Spijkervet FK, Brennan MT (2010) Fungal Infections Section, Oral Care Study Group, Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO). A systematic review of oral fungal infections in patients receiving cancer therapy. Support Care Cancer 18:985–992

Ishiki H, Onozawa Y, Kojima T, et al. (2012) Nutrition support for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with chemoradiotherapy: how often and how long? ISRN Oncol 2012:274739

Sciubba JJ, Goldenberg D (2006) Oral complications of radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol 7:175–183

Reuther T, Schuster T, Mende U, Kübler A (2003) Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws as a side effect of radiotherapy of head and neck tumour patients—a report of a thirty year retrospective review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 32:289–295

Murray CG, Daly TE, Zimmerman SO (1980) The relationship between dental disease and radiation necrosis of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 49:99–104

Marx RE, Johnson RP (1987) Studies in the radiobiology of osteoradionecrosis and their clinical significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 64:379–390

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Takeshi Kodaira, Yusuke Onozawa, Chiyoko Makita, Tomomi Hikosaka, Yukihiko Oshima, and Akiko Todaka for patient enrollment and Mr. Akihiro Sudo for oral care equipment management. This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (23-A-30) and by Sunstar Inc. Equipment for oral care was supplied by Sunstar Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Tomoya Yokota serves in an advisory role for AstraZeneca, Merck Serono, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and has received lecture fees from Merck Serono. Toru Eguchi is an employee of Sunstar Inc. Sunstar Inc. had no control over the interpretation, writing, or publication of this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yokota, T., Tachibana, H., Konishi, T. et al. Multicenter phase II study of an oral care program for patients with head and neck cancer receiving chemoradiotherapy. Support Care Cancer 24, 3029–3036 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3122-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3122-5