Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the present review was to determine effects of strength exercise on secondary lymphedema in breast cancer patients.

Methods

Research was conducted by using the databases PubMed/Medline and Embase. Randomized controlled trials published from January 1966 to May 2015 investigating the effects of resistance exercise on breast cancer patients with or at risk of secondary lymphedema in accordance with the American College of Sports Medicine exercise guidelines for cancer survivors were included in the present study.

Results

Nine original articles with a total of 957 patients met the inclusion criteria. None of the included articles showed adverse effects of a resistance exercise intervention on lymphedema status. In all included studies, resistance exercise intensity was described as moderate to high.

Conclusions

Strength exercise seems not to have negative effects on lymphedema status or might not increase risk of development of lymphedema in breast cancer patients. Further research is needed in order to investigate the effects of resistance exercise for patients suffering from lymphedema.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lymphedema (LE) is a relevant clinical problem of breast cancer patients. LE is a morbidity factor for breast cancer patients that causes limb swelling, lowers the function and mobility of the affected limb, and causes paresthesia. The prevalence rate of LE in the general population varies in a quite wide range [1, 2]. In patients suffering from cancer—particularly breast cancer—the prevalence and incidence rates of LE tend to be even higher [3–5].

Cancer-related LE reduces health-related quality of life (QoL) [6, 7]. As a consequence, breast cancer patients often do not use their affected arm, e.g., properly in their daily routine, as they fear this could worsen their condition [8, 9]. Additionally, LE causes a significant increase in healthcare costs [10].

Cancer-related LE can be caused not only by the disease itself but by necessary therapeutic measures such as radiation, chemotherapy, or lymphatic tissue destruction after surgery [3]. As an example, up to 30 % of breast cancer survivors (BCS) suffer from breast cancer-related LE (BCRL) after surgery [3]. This challenging problem of cancer-related LE is mainly addressed by interventions such as complex decongestive therapy as well as exercise and skin care [11]. Physical exercise is known to be useful not only for preventive goals but also as a therapeutic approach for a variety of medical, especially chronic, conditions such as cancer, hypertonia, osteoporosis, fat metabolism disorders, and many more [12–14]. Furthermore, literature shows beneficial effects of resistance exercise (RE) for cancer patients [15–17]. This furthers the question of exercise interventions for patients suffering from cancer-related LE, which is subject of intensive discussion in the current literature such as a recently published Cochrane review about BCRL and other articles show [18–20]. For example, Khwan et al. stated in a review that strong evidence is available on the safety of resistance exercise without an increase in risk of lymphedema for BCS [18]. Furthermore, Paskett et al. assumed even that exercise and physical activity reduce risk of LE [19]. In a Cochrane review, the authors assumed that progressive resistance exercise therapy does not increase the risk of developing lymphedema provided that symptoms are monitored and treated immediately if they occur. Nevertheless, due to the degree of heterogeneity, the limited precision, and the risk of bias across the reviewed studies, the authors concluded that the results should be interpreted with caution [20]. The aim of the present review was to investigate first, if RE increases the risk/causes the development specifically of BCRL and second, if patients with BCRL worsen, improve, or stay the same with RE.

Methods

A systematic review of the existing scientific literature was performed including the databases PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE. Trials with the key words “lymphedema,” respectively “lymphoedema,” and “strength exercise,” “resistance exercise,” “resistance training,” “weight training,” “weight lifting,” and “breast cancer” were extracted and considered for inclusion in the review. A total of 451 studies were found and screened for eligibility by title and abstract. Only English language studies were included. Four hundred and twenty-seven were rejected as non-includable and 24 studies were selected for full-text analysis (Fig. 1). Of these, nine fulfilled the inclusion criteria of being prospective randomized controlled studies investigating the influences of a RE intervention in accordance with the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) exercise guidelines for cancer patients [21] on the development of secondary lymphedema in breast cancer survivors [22–30]. The methodological quality of the included articles was assessed by implementing the risk of bias assessment tool of Downs and Black [31], which has been shown to be very helpful when comparing the quality of several trials [13, 32]. Both the systematic literature research and the risk of bias assessment were performed separately by two independent researchers. The integration of their individual findings was supervised by two senior researchers.

Results

Methodological quality

The risk of bias assessment revealed that the included studies ranged from 24 to 31 points of a maximum of 32 points (high score is a low bias) [31]. A weakness of all the included studies is that the participants could not be blinded to the interventions (Table 1, item 14 = internal validity—bias). On the other hand, all studies but Courneya et al. [26] reported an attempt to blind those measuring the main outcomes (Table 1, item 15). Further weaknesses are that only four studies recruited their patients from the same population (for example, patients for all comparison groups were recruited from the same hospital) [22, 23, 28, 29] (Table 1, item 21), only five provided a complete list of principal confounders [22, 23, 26, 29, 30] (Table 1, item 5), and three studies did not perform adequate adjustment for confounding in their analyses from which the main findings were drawn [23, 25, 28] (Table 1, item 25).

Eight of the nine included articles calculated a power analysis prior to the recruitment to reassure performing their exercise interventions with a sufficiently large sample [22, 24–30]. The detailed rating of the quality of included articles is presented in Table 1.

Lymphedema

While some of the included articles focused on changes in BCS with preexisting LE [24, 25, 27, 29], some others observed the volume of the upper extremities in BCS at risk of LE [23, 28, 30] or included BCS both with or without preexisting LE [22, 26].

Arm volume was evaluated in all of the included studies [22–30]. One or more assessment methods were used in the different studies: Water displacement volumetry was used in four articles [23, 26, 29, 30], limb circumference measurements in six [22, 24, 25, 28–30], bioimpedance spectroscopy in four [24, 25, 27, 28], dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in two [24, 25], and perometry in one [27] study. In the study by Ahmed et al., a validated survey for self-report of lymphedema diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment over the last 3 months was used additionally for limb circumference measurements [22, 33].

Schmitz et al. [30] used additionally (to water displacement volumetry and limb circumference measurements) the common toxicity criteria version 3.0 adverse events criteria as a clinical assessment method for LE, and lymphedema-related arm symptom presence and severity were reported using a validated and reliable survey for detecting prevalent lymphedema [33].

The other studies included validated self assessment tests to those methods listed before for LE development [23–25, 29]. Independent of assessment method, none of the studies reported significant detrimental effects of RE on LE status or risk of developing LE. On the contrary, Schmitz et al. [29] showed that during a 1-year weight-lifting program, the LE exacerbation rate was significantly lower in the exercise group than in the control group and Hayes et al. [27] even reported absence of signs of LE in two of 32 patients with preexisting LE by the end of the study.

Physical performance and function

Physical performance or function testing was conducted by all authors but Cormie et al. [25], who primarily focused on LE exacerbation and Hayes et al. [27], whose main focus was on the safety and benefits of an exercise intervention on LE.

Strength testing was performed in six of the included studies [22, 24, 26, 28–30], endurance testing in one [26], flexibility tests in two [24, 28], and physical function tests in one article [23]. In all of the studies that conducted physical performance tests [22–24, 26, 28–30], significant increases in at least one performance parameter were reported. The detailed results of the physical performance tests can be found in Table 2.

Body composition

A pre-post comparison of the body composition after an exercise intervention was performed by three studies [26, 29, 30]. Both Courneya et al. [26] and Schmitz et al. [29] did not find any significant changes neither in body fat percentage nor fat mass, while Schmitz et al. [30] reported a lower body fat percentage in the exercise group after 12 months of weight lifting compared to the no exercise control group.

Quality of life

Assessment of quality of life was performed by four studies [23, 24, 26, 28]. Anderson et al. [23] and Cormie et al. [24] used the FACT-B questionnaire, Courneya et al. [26] the FACT-Anemia-Scale, and Kilbreath et al. [28] the EORTC-BR23. In Courneya et al. [26], both exercise groups showed significantly higher self esteem values after the exercise intervention compared to the usual care group. The other studies did not report any significant differences between their exercise intervention and usual care groups [23, 24, 28].

Furthermore, Hayes et al. [27] recorded qualitative comments regarding the exercise program and the LE status and revealed the overarching concern that lymphedema impacts all facets of an individual’s life.

Safety

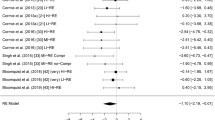

To show how safe RE programs have been in the included studies, we compiled an overview of the dropouts. In general, 44 dropped out of the 462 study participants (10 %) allocated to RE groups (Fig. 2). Not a single dropout was due to exercise-related LE complications. The adherence rate to strength exercise ranged in the majority of participants from 70 to 100 %. Details of drop out analysis are presented in Table 3.

Discussion

Breast cancer is by far the most common malignancy among women, with nearly one and a half million affected women worldwide [34]. For example, one out of eight women in the USA will be diagnosed with breast cancer over her lifetime [35]. Of those, more than one in five women who survive breast cancer will develop secondary LE, which is associated with a number of major impairments in activities of daily living and a substantial loss of quality of life [3]. Historically, BCS suffering from or at risk of secondary LE were instructed to refrain from vigorous, repetitive, or excessive upper body exercise, because there was a mutual belief within health care professionals that such type of exercises might induce LE although this assumption has never been backed up by evidence-based research [35].

Stuiver et al. conducted a Cochrane review on the effects of conservative (non-surgical and non-pharmacological) interventions for preventing clinically detectable upper limb lymphedema after breast cancer treatment. The authors stated that a progressive resistance exercise therapy does not increase the risk of developing lymphedema. These results of the Cochrane review are in accordance with the results of the present review. In contrast to Cochrane review, in the present systematic review, the effect of strength exercise on existing lymphedema was also considered. The results of this review revealed that strength exercise seems not to have negative effects on the existing lymphedema in breast cancer patients. As we have pointed out in this review, current literature does not support the assumption that a systematic RE program had detrimental effects on the development of secondary LE. On the contrary, we found that two studies even showed that individual patients experienced substantial improvements of their LE status [27, 29]. These results are far from being statistically significant but introduce the possibility that—under specific circumstances—RE might even preventative on the development of secondary LE. Therefore, it will be a major task for future research to identify those potentially beneficial factors. On the one hand, this means that future exercise programs will have to be evaluated in detail regarding RE intensity, volume, duration, frequency, and exercised muscle groups. As shown in Table 4, although all of the included studies complied with the exercise guidelines for breast cancer survivors [21], they still significantly differed between themselves. On the other hand, the current state of knowledge revealed that it will be necessary for future studies to thoroughly identify potential confounders. That is something that has not been done in all of the included studies, as was already shown in our risk of bias assessment (Table 1, items 5 and 25).

Ahmed et al. [22] noted that exercise might lead to physiological change in lymphatic structures and/or function. A possible pathway of how RE could positively influence the LE status in BCS could be deducted from the positive effects structured exercise has on the calf muscle pump in patients with chronic venous insufficiency [36]. RE of the upper extremities could have similar beneficial effects on the venous hemodynamics of the upper extremities, which in turn could support the lymphatic flow of the LE and then again lead to a reduction of swelling.

A major limitation of some of the reviewed articles was that not all of them used assessment methods for LE that would allow conclusions on the limb composition. Water displacement volumetry is described to be the gold standard for measuring limb volume [37, 38], and circumference measurements are inexpensive and, when correctly applied, also highly valid and reliable [39]. When conducting a structured RE program, it has to be considered that even without dietary monitoring, a positive muscle protein synthesis rate would most certainly be achieved in at least some of the participants [40]. Therefore, if the affected limb suffers from a LE-related swelling, by just measuring its volume or its circumference, potential increases in muscle cross-sectional area would not be detected. Nevertheless, indirect information about the LE status can be assessed by comparing the affected with the healthy arm, a method which also accounts for composition [22, 26, 29, 30]. Therefore, further studies are needed to improve our bulk of knowledge. In the discussion of definition and most appropriate assessment tool of LE, there is an absence of an agreed diagnostic definition of lymphedema due to its wide variation in different measurement techniques used in the literature and in daily routine. This might be to the fact that lymphedema assessment methods are concordant and reliable but not interchangeable. Furthermore, no consensus on golden standard of lymphedema measurement is available in the literature [19].

Another major concern regarding a RE intervention for BCS was mentioned by Hayes et al. [27], who recorded qualitative comments regarding the exercise program and the LE status. He found out that many patients sensed grief and frustration and became uncertain about the likely outcome of LE treatment because of conflicting advice from health professionals regarding the exercise intervention. It is therefore of substantial importance that, when planning a RE intervention study with BCS, all health professionals that may get in contact with the study participants receive sufficient information material about the current evidence ahead of time.

A limitation of the present systematic review is that due to the limited number of eligible studies and the heterogeneity of the RE interventions, we did not perform a meta-analysis. This narrow width of evidence-based scientific knowledge together with the presence of unbacked and out of date assumptions regarding RE and LE shows how important it is on the one hand to gain new evidence and on the other hand, to share the insights of this review about the current state of knowledge with health care professionals working with BCS. With this newly acquired knowledge, maybe more health care specialists will set aside their fear of performing RE with BCS. This would not only be beneficial for the patients but could also be very helpful in boosting the data collection process. We suggest that a minimum of about 20 high-quality RCTs would be necessary in total for being able to conduct a thorough meta-analysis.

It can be concluded that—at the moment—the scientific literature does not give any contraindications of RE for BCS suffering or at risk of BCRL when performed according to the ACSM guidelines for cancer survivors [21]. RE interventions seem to be safe, feasible, and beneficial regarding physical performance in patients with or at risk of BCRL. If RE could actually be beneficial for the LE status remains open for future research.

References

Rabe E, Pannier-Fischer F, Bonner (2007) Venenstudie der deutschen Gesellschaft für Phlebologie-Epidemiologische Untersuchung zur Frage der Häufigkeit und Ausprägung von chronischen Venenkrankheiten in der städtischen und ländlichen wohnbevölkerung. Phlebologie 32:1–14

Pannier F, Hoffmann B, Stang JK, Rabe E (2007) Prevalence of Stemmer’s sign in the general population—results from the Bonn Vein Study. Phlebologie 36:287–342

DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, Hayes S (2013) Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet oncology 14:500–515

Cormier JN, Askew RL, Mungovan KS, Xing Y, Ross MI, Armer JM (2010) Lymphedema beyond breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cancer-related secondary lymphedema. Cancer 116:5138–5149

Oberaigner W, Geiger-Gritsch S (2014) Prediction of cancer incidence in Tyrol/Austria for year of diagnosis 2020. Wien Klin Wochenschr 126:642–649

Ahmed RL, Prizment A, Lazovich D, Schmitz KH, Folsom AR (2008) Lymphedema and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 26:5689–5696

Cormier JN, Xing Y, Zaniletti I, Askew RL, Stewart BR, Armer JM (2009) Minimal limb volume change has a significant impact on breast cancer survivors. Lymphology 42:161–175

Lymphedema: what every woman with breast cancer should know: American Cancer Society; [cited 2014 26.08]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatmentsandsideeffects/physicalsideeffects/lymphedema/whateverywomanwithbreastcancershouldknow/lymphedema-with-breast-cancer-if-at-risk-for-lymphedema.

Schmitz KH (2010) Balancing lymphedema risk: exercise versus deconditioning for breast cancer survivors. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 38:17–24

Shih YC, Xu Y, Cormier JN, et al. (2009) Incidence, treatment costs, and complications of lymphedema after breast cancer among women of working age: a 2-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 27:2007–2014

Liebl ME, Preiß S, Pögel S, et al. (2014) Elastic tape as a therapeutic intervention in the maintenance phase of complex decongestive therapy (CDT) in lymphedema. Phys Med Rehab Kuror 24:34–41

Crevenna R, Zielinski C, Keilani MY, et al. (2003) Aerobic endurance training for cancer patients. Wien Med Wochenschr 153:212–216

Hasenoehrl T, Keilani M, Sedghi Komanadj T, et al. (2015) The effects of resistance exercise on physical performance and health-related quality of life in prostate cancer patients: a systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 23:2479–2497

Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara AV, Koes BW (2005) Meta-analysis: exercise therapy for nonspecific low back pain. Ann Intern Med 142:765–775

Kampshoff CS, Buffart LM, Schep G, van Mechelen W, Brug J, Chinapaw MJ (2010) Design of the Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study: a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of exercise interventions after chemotherapy on physical fitness and fatigue. BMC Cancer 10:658

Battaglini CLMR, Phillips BL, Lee JT, Story CE, Nascimento MG, Hackney AC (2014) Twenty-five years of research on the effects of exercise training in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of the literature. World J Clin Oncol 5:177–190

Strasser BSK, Wiskemann J, Ulrich CM (2013) Impact of resistance training in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45:2080–2090

Kwan ML, Cohn JC, Armer JM, Stewart BR, Cormier JN (2011) Exercise in patients with lymphedema: a systematic review of the contemporary literature. J Cancer Surviv: Res Pract 5:320–336

Paskett ED, Dean JA, Oliveri JM, Harrop JP (2012) Cancer-related lymphedema risk factors, diagnosis, treatment, and impact: a review. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 30:3726–3733

Stuiver MM, ten Tusscher MR, Agasi-Idenburg CS, Lucas C, Aaronson NK, Bossuyt PM (2015) Conservative interventions for preventing clinically detectable upper-limb lymphoedema in patients who are at risk of developing lymphoedema after breast cancer therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD009765

Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, Irvin ML, Wolin KY, Segal RJ, Lucia A, Schneider CM, von Grueningen VE, Schwartz AL (2010) American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42:1409–1426

Ahmed RL, Thomas W, Yee D, Schmitz KH (2006) Randomized controlled trial of weight training and lymphedema in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 24:2765–2772

Anderson RT, Kimmick GG, McCoy TP, et al. (2012) A randomized trial of exercise on well-being and function following breast cancer surgery: the RESTORE trial. J Cancer Surviv: Res Pract 6:172–181

Cormie P, Pumpa K, Galvao DA, et al. (2013) Is it safe and efficacious for women with lymphedema secondary to breast cancer to lift heavy weights during exercise: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv: Res Pract 7:413–424

Cormie P, Galvao DA, Spry N, Newton RU (2013a) Neither heavy nor light load resistance exercise acutely exacerbates lymphedema in breast cancer survivor. Integr Cancer Ther 12:423–432

Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, Gelmon K, Reid RD, Friedenreich CM, et al. (2007) Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 25:4396–4404

Hayes SC, Reul-Hirche H, Turner J (2009) Exercise in secondary lymphedema: safety, potential benefits, and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41:483–489

Kilbreath SL, Refshauge KM, Beith JM, et al. (2012) Upper limb progressive resistance training and stretching exercises following surgery for early breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 133:667–676

Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, et al. (2009) Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med 361:664–673

Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, et al. (2010) Weight lifting for women at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized trial. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc 304:2699–2705

Downs SH, Black N (1998) The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 52:377–384

Gardner JR, Livingston PM, Fraser SF (2014) Effects of exercise on treatment-related adverse effects for patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen-deprivation therapy: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 32:335–346. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.5523

Cheville AL, McGarvey CL, Petrek JA, Russo SA, Thiadens SR, Taylor ME (2003) The grading of lymphedema in oncology clinical trials. Semin Radiat Oncol 13:214–225

Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Dunn NAM, Mullen JM, Pyke CM, Baade PD (2012) The descriptive epidemiology of female breast cancer: an international comparison of screening, incidence, survival and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol 36:237–248

Harris SR, Niesen-Vertommen SL (2000) Challenging the myth of exercise-induced lymphedema following breast cancer: a series of case reports. J Surg Oncol 74:95–99

Padberg Jr FT, Johnston MV, Sisto SA (2004) Structured exercise improves calf muscle pump function in chronic venous insufficiency: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg 39:79–87

Kaulesar Sukul D, den Hoed P, Johannes E, van Dolder R, Benda E (1993) Direct and indirect methods for the quantification of leg volume: comparison between water displacement volumetry, the disk model method and the frustum sign model method, using the correlation coefficient and the limits of agreement. J Biomed Eng 15:477–480

Sander AP, Hajer NM, Hemenway K, Miller AC (2002) Upper-extremity volume measurements in women with lymphedema: a comparison of measurements obtained via water displacement with geometrically determined volume. Phys Ther 82:1201–1212

Taylor R, Jayasinghe UW, Koelmeyer L, Ung O, Boyages J (2006) Reliability and validity of arm volume measurements for assessment of lymphedema. Phys Ther 86:205–214

Phillips SM (2014) A brief review of critical processes in exercise-induced muscular hypertrophy. Sports Med 44(Suppl 1):S71–S77

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keilani, M., Hasenoehrl, T., Neubauer, M. et al. Resistance exercise and secondary lymphedema in breast cancer survivors—a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 24, 1907–1916 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3068-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3068-z