Summary

Background

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system. Inflammation may create high susceptibility to subclinical atherosclerosis. The purpose of this study was to compare subclinical atherosclerosis and the role of inflammatory cytokines between the group of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) and healthy controls matched for age and sex.

Methods

The study group consisted of 112 non-diabetic and non-hypertensive RRMS patients treated with disease modifying drugs (DMD) and the control group was composed of 51 healthy subjects. The common carotid artery (CCA) intima media thickness (IMT) was investigated. Serum levels of risk factors for atherosclerosis and inflammatory cytokines were also determined.

Results

The mean CCA IMT (0.572 ± 0.131 mm vs. 0.571 ± 0.114 mm) did not differ (p > 0.05) between patients and controls. The RRMS patients’ CCA IMT was significantly correlated with serum interleukin 6 (IL-6) (p = 0.027), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) (p = 0.027), cystatin C (p < 0.0005), glucose (p = 0.031), cholesterol (p = 0.008), LDL (p = 0.021), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (p = 0.001) and triglyceride (p = 0.018) level. We fitted generalized linear models in order to assess the relationship between CCA IMT and IL‑6 with adjustment for sex and age. The obtained results showed that adjusted for age (p < 0.001) and sex (p = 0.048) IL‑6 serum levels statistically significantly (p = 0.009) predict CCA IMT only in the RRMS group.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study suggest that when treated with DMD RRMS might not be an independent risk factor for early atherosclerosis presenting with arterial wall thickening; however, the results suggest a significant association of IL‑6 serum levels with CCA IMT only in the RRMS group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a common, inflammatory, disabling, immune-mediated and chronic disorder of the central nervous system [1]. The prevalence and incidence of MS are higher in the western world [2]. Early treatment is an important factor in the prolonged survival [2, 3] of patients with MS. Age-related vascular diseases are a very important part of the spectrum of conditions associated with MS [4]. Inflammation is present in all stages of multiple sclerosis and may create high susceptibility to subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis [5]. Subclinical atherosclerosis has been inconsistently investigated in MS [5]. Atherosclerosis, like MS, is a complex and chronic inflammatory disease [6]. It involves an inflammatory fibroproliferative response and has an autoimmune component [6]. Carotid intima media thickness (cIMT) is considered as an early indicator for (subclinical) atherosclerosis [6]. Elevated proinflammatory cytokines are characteristic for both diseases (MS and atherosclerosis) [5, 6]. A very important and yet unanswered question is whether patients with MS have an increased risk for diseases associated with atherosclerosis, such as ischemic stroke, coronary disease and peripheral vascular disease. [7,8,9,10]. Some studies indicated that vascular disease is a significant cause of death in patients with MS [9]. The existence of any vascular risk factor is associated with the faster onset of walking disability in patients with MS [11, 12]. Currently, it is not fully understood why certain vascular risk factors affect the disability but it is believed that chronic inflammation of the arteries plays an important role [13].

The purpose of this study was to compare subclinical atherosclerosis between patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) treated with disease modifying drugs (DMD) without vascular risk factors and healthy control subjects, matched for age and sex.

Material and methods

Patients and methods

The study group included 112 non-diabetic and non-hypertensive RRMS patients (mean age 40.66 ± 8.95) treated with DMD. They were recruited in a consecutive manner from the outpatient unit of Department of Neurology at the University Medical Centre (UMC) Maribor in Slovenia in the year 2018. The MS patients were diagnosed according to the McDonald criteria [14, 15]. As a control group 51 healthy subjects matched by age and sex were selected from hospital personnel. The exclusion criteria were diabetes mellitus, hypertension, known coagulopathy or platelet disease, malignant or infectious diseases and known cardiovascular disease or past cardiovascular event. Patients with RRMS without DMD were also excluded. Written informed consents were obtained from all participants included in the study. This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the national ethics committee (reference number: 0120-539/2017‑3, KME 23/10/17).

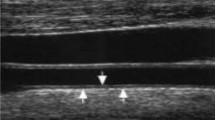

Ultrasonographic scanning of the carotid artery was performed in MS patients and healthy controls. It was done with high-resolution echo color Doppler ultrasonography with a multifrequency 5–10 MHz linear probe on the General Electric Logiq 7 system (Yokogawa Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan). The subjects were placed in a supine position with slightly hyperextended necks and were rotated away from the imaging transducer. Three clearly visible images that were captured in real time on the cineloop frame grabber were used for analysis. A fourfold magnification was used for image display and analysis of both carotid arteries. The IMT was examined in the common carotid arteries (CCA) and in the area of bifurcation (BIF). The same definition of IMT was applied as in the other studies [16,17,18,19,20,21,22] and IMT was defined as the distance between the leading edge of the media adventitia interface of the far wall. A plaque-free area was used for IMT measurements. The average value was calculated from the same section of the artery. All the measurements were performed by the same trained and licensed examiner who was blinded to the clinical characteristics of the subjects.

The patients were evaluated using the multiple sclerosis functional composite (MSFC) scale and the expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Both instruments are frequently used as an endpoint in clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of DMD and as tools to assess disability (progression) in patients with MS [23]. Kurtzke defined the EDSS [24] as a clinician-administered valuation scale assessing the functional systems of the central nervous system. The EDSS consists of an ordinal score system [24]. The values range from 0 (normal neurological status) to 10 (death due to MS) in 0.5 intervals (after reaching EDSS 1) [24]. Walking ability/disability heavily determines EDSS values above 4.0 [24]. Another disability assessment tool, the MSFC [25], was developed by the MS Society’s clinical assessment task force [26] as another clinical scale of MS disability progression. The main purpose for creating the MSFC was to expand the existing measure of MS disability for clinical trials and to develop a multidimensional metric system of complete MS clinical condition [26]. The MSFC consists of a three-part performance scale for assessing the degree of impairment in patients with MS. It consists of the evaluation of leg function (timed 25-foot walk, T25FW), the evaluation of arm/hand function (9-hole peg test, 9HPT) and an attention/concentration test to evaluate higher cortical functions (paced auditory serial addition test, PASAT) [26]. A combined and united MSFC score is calculated using Z‑scores [26].

The RRMS patient and healthy control serum levels of high-sensitivity C‑reactive protein (hs-CRP), total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF α), creatinine, uric acid, homocysteine, cystatin C, erythrocytes, leukocytes, hemoglobin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and hematocrit were measured by routine laboratory methods at the UMC Maribor.

Statistical analysis

Values were expressed as the mean ± SD unless indicated otherwise. Data was analysed with SPSS Statistics 24.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Student’s t‑test was used to compare mean values between the groups. Associations of categorical variables were tested using χ2-testor Fisherʼs exact test. Differences of continuous variables between two independent groups were determined using Mann-Whitney U‑test after Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality. Correlations between continuous variables were assessed using Spearman’s correlations after Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality. Regression models were fitted using generalized linear models with CCA IMT as linear dependent variable. Models were built using disability measures, cystatin C or IL‑6 serum levels adjusted for sex as factor and age at CCA measurement as covariate. Additionally, generalized linear models and pairwise Kruskal-Wallis H‑test were used to assess association of DMD with CCA IMT (adjusted to age at CCA IMT measurement) and IL‑6 serum levels, respectively. P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 112 RRMS patients included in the study, 78 (69.6%) were female and the control group comprised 35 (68.6%) females. Baseline characteristics of patients and healthy controls are shown in Table 1. Additional characteristics of MS patients are presented in Table 2. We found no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in CCA IMT values between RRMS patients treated with DMD (0.572 ± 0.131 mm) and healthy controls (0.571 ± 0.114 mm). Mean BIF IMT (0.736 ± 0.171 mm vs. 0.758 ± 0.194 mm) also did not differ between patients (mean age 40.66 ± 8.95 years) and healthy controls (mean age 40.45 ± 9.54 years), but in both groups mean BIF IMT was significantly higher than mean CCA IMT (p < 0.01).

There was no statistically significant difference between RRMS patients and healthy controls in smoking status, age and BMI.

The RRMS patients had statistically significant lower values of serum creatinine (65.29 ± 12.37 mmol/L vs. 72.84 ± 13.27 mmol/L; p < 0.001), serum uric acid (238.24 ± 79.36 µmol/L vs. 255.96 ± 57.73 µmol/L,p = 0.041) and glucose (4.660 ± 0.931 mmol/L vs.4.743 ± 0.536 mmol/L, p = 0.047) than healthy controls. No significant difference was observed in total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides serum levels between groups.

In the RRMS group statistically significant positive correlations between average CCA IMT values and EDSS (ρ = 0.222, p = 0.019), T25FW (ρ = 0.317, p = 0.001) and dominant hand on 9HPT (ρ = 0.221, p = 0.019) were found.

Subsequently, correlations of CCA IMT and laboratory parameters were performed and are presented in Table 3.

The CCA IMT values were also positively correlated with RRMS patient age (ρ = 0.729, p < 0.001) and BMI (ρ = 0.285, p = 0.002). Healthy controls’ age (ρ = 0.702, p < 0.01) and BMI (ρ = 0.351, p = 0.013) were also correlated with CCA IMT.

In addition to the correlations, we fitted generalized linear models in order to assess the relationship between CCA IMT and disability measures, cystatin C or IL‑6 with adjustment for sex and age. Analyses were performed using RRMS patients and healthy controls divided datasets.

For testing of disability measures, models were fitted using only RRMS patients’ dataset. When adjusted for the aforementioned covariates, EDSS, T25FW and 9HPT did not prove to be predictors of CCA IMT, while age and sex remained significant predictors of CCA IMT (Table 4).

The obtained results showed that in RRMS patients IL‑6 serum levels (p = 0.009), age (p < 0.001) and sex (p = 0.048) statistically significantly predicted CCA IMT (Table 5). On the other hand, using only healthy controls dataset, IL‑6 serum levels did not significantly predict CCA IMT, while age (p < 0.001) remained a statistically significant predictor in the fitted model (Table 5).

Moreover, the same models were fitted in order to assess the relationship between CCA IMT and cystatin C serum levels. The results showed no significant prediction of cystatin C serum levels regardless of the dataset (Table 6). Only a significant prediction of age (p < 0.001) in both RRMS and healthy controls groups was observed.

Additionally, the associations of CCA IMT and IL‑6 serum levels with DMD were assessed but no statistically significant differences were observed.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that there is no statistically significant difference in carotid IMT (CCA and BIF), which is an indicator of asymptomatic atherosclerosis [27, 28], between RRMS patients treated with DMD and healthy controls. It is the first study with homogeneous RRMS treated with DMD cohort with more than 35 patients. Yuksel et al. [29] analyzed cIMT and hs-CRP in RRMS patients with DMD. Their study [29] included 35 RRMS patients treated with DMD and 34 healthy controls. The mean age of our RRMS study population (40.66 ± 8.95 years) was slightly higher than theirs (37.1 ± 7.6 years). There was less difference between the mean age between RRMS patients and healthy controls in our study (40.66 ± 8.95 years vs. 40.45 ± 9.54 years, p > 0.05) than in the study from Yuksel et al. (37.1 ± 7.6 years vs. 34.5 ± 6.3 years, p > 0.05) [29], although both differences were not statistically significant. Mean cIMT was significantly greater in the patient population in their study, while there was also a difference in hs-CRP serum level between RRMS patients (0.5 mg/L) and healthy controls (1.2 mg/L) [29]. The difference in cIMT thickness (0.6 ± 0.1 mm vs. 0.5 ± 0.07 mm) in their study could be partly explained by the average age difference between the groups, as RRMS patients were on average slightly older. The average finding of lower hs-CRP values in the RRMS group in their study could be due to reduced inflammation due to DMD, but the finding was not confirmed in the cohort from our study.

Only nondiabetic normotensive male and female RRMS patients treated with DMD were included in our study. The findings suggest that RRMS itself, when treated with DMD may not be an independent risk factor for early atherosclerosis presented with arterial wall thickening. Nevertheless, further studies should be done to assess the role of subclinical atherosclerosis in RRMS patients who are not treated with DMD and in patients with progressive MS with and without DMD.

A study by Dagan et al. [30] that assessed the prevalence and potential association of hypertension with MS-related disability progression revealed that disability progression was more prevalent amongst hypertensive MS patients; however, hypertensive MS patients experienced longer time intervals between the stages of disability progression. Patients’ cIMT was not assessed in this study. Our study included only normotensive patients but a positive correlation between the severity of disability (EDSS) and CCA IMT was noticed. To our knowledge, it is also the first study that found a positive association between CCA IMT and leg function (T25FW) and between CCA IMT and hand function (9HPT); however, with adjustment of disability measures for sex and age, only sex and age were predictive of CCA IMT.

Among many different markers of inflammation, the CRP was proven to be a strong prognosticator of vascular diseases independent of serum lipid levels [31,32,33,34]. The CRP can also be engaged in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis [33]. An association between hs-CRP and CCA IMT was revealed in both groups in our study; however, no elevated hs-CRP levels in RRMS patients’ serum were found compared with healthy controls. Moreover, we found that CCA IMT was associated with cystatin C and IL‑6 serum levels only in RRMS group and not in healthy controls group. Cystatin C is a known potential marker of early stage atherosclerosis [35] but the literature lacks sound data on the role of cystatin C in MS. Furthermore, IL‑6 serum levels were found to be associated with CCA IMT regardless of the adjustment for RRMS patient sex and age. Despite predictive value of patient age and sex, IL‑6 serum levels remained highly significant predictors for CCA IMT. The IL‑6 is a crucial inflammatory cytokine [36]. It stimulates the inflammatory process that influences the atherosclerosis [36]. Many diseases (acute infections, chronic inflammatory diseases, such as MS) stimulate IL‑6 release [36]. Elevated serum levels of IL‑6 found in such disorders/illnesses have multiple functions, including being an important mediator of fever and of acute phase response, altering the function of endothelial cells, elevated coagulation risk, and promotion of lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation [36].

A positive correlation was also found between CCA IMT values and serum cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides and glucose levels. Therefore, we cannot completely exclude the additional role of traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis even in normotensive and nondiabetic RRMS patients treated with DMD.

The limitation of the present study is that patients with RRMS without DMD and patients with progressive form of MS were not included. Most patients with RRMS in our hospital are treated with DMD, so it would be very difficult to find a comparable group of patients without DMD. Moreover, patients with progressive forms of MS are usually older and have more comorbidities, such as hypertension that could have an additional impact on atherosclerosis. Additionally, people from Central Europe were included.

Conclusion

The study findings suggest that RRMS itself, when treated with DMD, may not be an independent risk factor for early atherosclerosis presented with arterial wall thickening. The RRMS group’s CCA IMT was significantly correlated with disability measures, cystatin C, IL‑6, hs-CRP, ESR serum levels and with some traditional serum risk factors for atherosclerosis. Moreover, the obtained results suggest a significant association of IL‑6 serum levels with CCA IMT in RRMS patients. Despite the significant prediction of CCA IMT by age and sex, adjusted IL‑6 levels also proved to be a highly significant predictor of CCA IMT in RRMS patients. Nevertheless, further studies are warranted to assess the role of subclinical atherosclerosis in RRMS patients who are not treated with DMD and in patients with progressive MS with and without DMD.

References

Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG. Disease modifying therapies for relapsing multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2016;354:i3518. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3518.

Solaro C, Ponzio M, Moran E, et al. The changing face of multiple sclerosis: prevalence and incidence in an aging population. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1244–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458514561904.

Lunde HMB, Assmus J, Myhr KM, et al. Survival and cause of death in multiple sclerosis: a 60-year longitudinal population study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:621–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2016-315238.

Marrie RA. Comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: implications for patient care. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:375–82. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.33.

Ranadive SM, Yan H, Weikert M, et al. Vascular dysfunction and physical activity in multiple sclerosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(2):238–43. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31822d7997.

Singh RB, Mengi SA, Xu YJ, et al. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a multifactorial process. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2002;7:40–53.

Roshanisefat H, Bahmanyar S, Hillert J, et al. Multiple sclerosis clinical course and cardiovascular disease risk—Swedish cohort study. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:1353–e88. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12518.

Christiansen CF. Risk of vascular disease in patients with multiple sclerosis: a review. Neurol Res. 2012;34(8):746–53. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743132812Y.0000000051.

Thormann A, Magyari M, Koch-Henriksen N, et al. Vascular comorbidities in multiple sclerosis: a nationwide study from Denmark. J Neurol. 2016;263:2484–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-016-8295-9.

Marie RA, Reider N, Cohen J, et al. A systematic review of incidence and prevalence of cardiac, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular disease in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21:318–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458514564485.

Manouchehrinia A, Tench CR, Maxted J, et al. Tobacco smoking and disability progression in multiple sclerosis: United Kingdom cohort study. Brain. 2013;136(Pt7):2298–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt139.

Marrie RA, Rudick R, Horwitz R, et al. Vascular comorbidity is associated with more rapid disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;74:1041–7. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d6b125.

Gisterå A, Hansson GK. The immunology of atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:368–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2017.51.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22366.

Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:162–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2.

Craven TE, Ryu JE, Espeland MA, et al. Evaluation of the association between carotid artery atherosclerosis and coronary artery stenosis: a case control study. Circulation. 1990;82:1230–42. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.82.4.1230.

Burdick L, Periti M, Salvaggio A, et al. Relation between carotid artery atherosclerosis and time on dialysis. A non-invasive study in vivo. Clin Nephrol. 1994;42:121–6.

London GM, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, et al. Cardiac and arterial interactions in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 1996;50:600–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1996.355.

Piggnoli P, Tremoli E, Poli A, et al. Intimal plus medial thickness of the arterial wall: a direct measurement with ultrasound imaging. Circulation. 1986;74:1399–406.

Kawagishi T, Nishizawa Y, Konishi T, et al. High-resolution B‑mode ultrasonography in evaluation of atherosclerosis in uremia. Kidney Int. 1995;48(3):820–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1995.356.

Savage T, Clarke AL, Giles M, et al. Calcified plaque is common in the carotid and femoral arteries of dialysis patients without clinical vascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:2004–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/13.8.2004.

Pahor A, Hojs R, Gorenjak M, et al. Accelerated atherosclerosis in pre-menopausal female patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2006;27(2):119–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-006-0176-6.

Meyer-Moock S, Feng YS, Maeurer M, et al. Systematic literature review and validity evaluation of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-14-58.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale. Neurology. 1983;5:580–3. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.33.11.

Cutter GR, Baier ML, Rudick RA, et al. Development of a multiple sclerosis functional composite as a clinical trial outcome measure. Brain. 1999;122:871–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/122.5.871.

Fischer JS, Rudick RA, Cutter GR, Reingold SC. The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite Measure (MSFC): an integrated approach to MS clinical outcome. National MS Society Clinical Outcomes Assessment Task Force. Mult Scler. 1999;5(4):244–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/135245859900500409.

Piko N, Ekart R, Bevc S, et al. Atherosclerosis, epigenetic modifications, and arterial stiffness. Acta Medico-Biotechnica. 2017;10(2):10–7.

Simons PC, Algra A, Bots ML, et al. Common carotid intima-media thickness and arterial stiffness: indicators of cardiovascular risk in high-risk patients. The SMART Study (Second Manifestations of ARTerial disease). Circulation. 1999;100(9):951–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.100.9.951.

Yuksel B, Koc P, Ozaydin Goksu E, et al. Is multiple sclerosis a risk factor for atherosclerosis? J Neuroradiol. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurad.2019.10.002.

Dagan A, Gringouz I, Kliers I, et al. Disability progression in multiple sclerosis is affected by the emergence of comorbid arterial hypertension. J Clin Neurol. 2016;12(3):345–50. https://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2016.12.3.345.

Danesh J, Whincup P, Walker M, et al. Low grade inflammation and coronary heart disease: prospective study and updated meta-analyses. BMJ. 2000;321:199–204. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7255.199.

Kirbis S, Breskvar UD, Sabovic M, et al. Inflammation markers in patients with coronary artery disease—comparison of intracoronary and systemic levels. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2010;122:31–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-010-1343-z.

Ridker PM, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH. C‑reactive protein adds to the predictive value of total and HDL cholesterol in determining risk of first myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:2007–11. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.97.20.2007.

Alber HF, Suessenbacher A, Weidinger F. Die Rolle der Inflammation in der Pathophysiologie akuter Koronarsyndrome. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117(13/14):445–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-005-0399-7. The role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of acute coronary syndromes.

Kaneko R, Sawada S, Tokita A, et al. Serum cystatin C level is associated with carotid arterial wall elasticity in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a potential marker of early-stage atherosclerosis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.003.

Hartman J, Frishman W. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: a review of the role of Interleukin‑6 in the development of atherosclerosis and the potential for targeted drug therapy. Cardiol Rev. 2014;22(3):147–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/CRD.0000000000000021.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by University Medical Centre Maribor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Tomaž Omerzu, Jožef Magdič, Radovan Hojs, Uroš Potočnik, Mario Gorenjak and Tanja Hojs Fabjan. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Tomaž Omerzu and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

T. Omerzu, J. Magdič, R. Hojs, U. Potočnik, M. Gorenjak and T.H. Fabjan declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Omerzu, T., Magdič, J., Hojs, R. et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr 136, 40–47 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-021-01862-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-021-01862-7