Abstract

Background

Persistent proteinuria seems to be a risk factor for progression of renal disease. Its reduction by angiotensin-converting inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) is renoprotective. Our previous pilot study showed that 2-year lisinopril therapy is effective and safe for children with mild IgA nephropathy. When combined with ACEI and ARB, reported results are of greater decrease in proteinuria than monotherapy in chronic glomerulonephritis, including IgA nephropathy. To date, however, there have been no randomized controlled trials in children.

Methods

This is an open-label, multicenter, prospective, and randomized phase II controlled trial of 63 children with biopsy-proven proteinuric mild IgA nephropathy. We compared efficacy and safety between patients undergoing lisinopril monotherapy and patients undergoing combination therapy of lisinopril and losartan to determine better treatment for childhood proteinuric mild IgA nephropathy.

Results

There was no difference in proteinuria disappearance rate (primary endpoint) between the two groups (cumulative disappearance rate of proteinuria at 24 months: 89.3% vs 89% [combination vs monotherapy]). Moreover, there were no significant differences in side effects between the two groups.

Conclusions

We propose lisinopril monotherapy as treatment for childhood proteinuric mild IgA nephropathy as there are no advantages of combination therapy.

Clinical trial registration

Clinical trial registry, UMIN ID C000000006, https://www.umin.ac.jp.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common primary glomerulonephritis. Although thought to be a benign disease with a favorable prognosis, data from long-term follow-up studies have revealed that the disease progresses to renal failure in 20–50% of adult patients [1, 2]. Although prognosis of IgAN is thought to be more benign in children, the results of recent studies do not support this [3]. IgAN usually has a progressive disease course, including some cases with minimal proteinuria at onset [4]. Even in children with mild IgAN showing minimal or focal mesangial proliferation (FMP; defined as less than 80% of glomeruli showing moderate or severe mesangial cell proliferation, i.e., more than three cells per peripheral mesangial area, according to World Health Organization criteria), persistent proteinuria is a risk factor for progression of the disease [3], indicating the need for an effective and safe treatment.

Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) can reduce proteinuria and show renoprotective effect [5,6,7]. Combination therapies with an ACEI and an ARB may result in a greater decrease in proteinuria than monotherapy [8, 9]. Our pilot study showed that 2-year lisinopril (ACEI) therapy is effective and safe for children with mild IgAN [10].

The present study is designed to test the safety and efficacy of combination therapy of lisinopril and losartan (ARB) compared with lisinopril monotherapy for children with mild IgAN showing minimal or FMP and persistent proteinuria.

Materials and methods

Patients

The study was approved by the institutional review board at each center and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written assent was obtained from patients who were old enough to understand and written informed consent was obtained from all of their parents.

Patients were registered at 19 centers in Japan. They were randomized to lisinopril monotherapy group (group A) or combination therapy group of lisinopril and losartan (group B) between April 26, 2005 and January 27, 2010. Criteria to enter the study were as follows: (1) biopsy-proven IgA nephropathy with FMP within 12 months before enrollment, (2) early morning urinary protein to creatinine ratio (uP/Cr) > 0.2 g/g, (3) aged 2–18 years. Exclusion criteria were (1) Henoch-Schönlein nephritis, (2) systemic lupus erythematosus, (3) medical history of allergy or hypersensitive reactions to lisinopril or losartan, (4) ≥ stage III chronic kidney disease (defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] less than 60 ml/min/1.73m2), (5) active infections, (6) severe liver dysfunction, (7) any treatment with steroids, immunosuppressants, ACEI, ARB, dipyridamole, or Saireito, a kind of Japanese herbal medicine, which is used for the reduction of proteinuria, and (8) pregnancy.

A pathologist in our group (NY) evaluated each renal biopsy specimen by light microscopy and was unaware of the patients’ clinical data at entry into the study. Diagnosis of IgAN was based on the presence of IgA as the sole or predominant immunoglobulin in the glomerular mesangium without systemic disease [11]. FMP was defined as less than 80% of glomeruli showing moderate or severe mesangial cell proliferation, i.e., more than three cells per peripheral mesangial area on the basis of the World Health Organization criteria. The extent of tubular atrophy was semiquantitatively graded on a scale from 0 to 3+ (none, 0; narrow, 1+; moderate, 2+; and wide, 3+). Immunofluorescence microscopy slides were examined by the pathologist at each center. The intensity of deposits on immunofluorescence microscopy was graded semiquantitatively on a scale from 0 to 3+: (none, 0; slight, 1+; moderate, 2+; and intense, 3+).

Trial design

JSKDC01 study was an open-label, multicenter, prospective, randomized phase II controlled trial. We adopted the selection design proposed by Simon [12] and generalized by Sargent et al. [13], which is often used to choose which therapy warrants phase III trial, typically in a limited number of patients. Although it does not bring a confirmatory result based on a p value, it has the advantage of being able to evaluate treatments under comparable situations.

This trial aims to select a “better” treatment for mild IgAN in children by comparing two regimens: lisinopril monotherapy or combination therapy of lisinopril and losartan. A statistically significant difference in primary endpoint between the two groups was not needed in this trial. The selection rule was as follows: if the disappearance rate of proteinuria at 24 months in group B was superior to that in group A by more than 10%, the combination regimen was selected as the better treatment. Otherwise, the group A regimen was selected. The selection threshold of 10% was set before the start of the study, based on a consensus reached by pediatric nephrologists in the JSKDC consideration of a potential risk of overtreatment.

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to group A and group B at the data center, using the covariate adaptive randomization adjusting age (1–10 years or 11–18 years), sex, and institutions.

The planned sample size was 110. This sample size assures more than 80% chance of selecting the group B regimen when the true the disappearance rate of proteinuria at 24 months is 75% in group A and 90% in group B.

This trial is registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network clinical trial registry, number C000000006.

Experimental intervention

Within 30 days after randomization, the experimental intervention was commenced. All patients received once-daily treatment with lisinopril 0.1 mg/kg body weight (maximum 5 mg/day). In group A patients, within 6 months, this was increased to 0.4 mg/kg (maximum 20 mg/day) for the remaining 18 months.

In group B patients, after the same course as patients in group A, once-daily treatment with losartan 0.7 mg/kg body weight (maximum 50 mg/day) was added and within 6 months, doses of lisinopril and losartan were increased to 0.4 mg/kg (maximum 20 mg/day) and 1.0 mg/kg body weight per day (maximum 100 mg/day), respectively, for the remaining 18 months.

The use of immunosuppressive agents, prednisolone, other kinds of ACEI and ARB, dipyridamole, and Saireito was prohibited during the trial. The experimental intervention was stopped if (1) patients developed early morning uP/Cr > 1.0 g/g lasting for 6 months during the trial, (2) patients developed < 3.0 g/dl serum albumin during the trial, (3) patients had < 60 mL/m/1.73m2 eGFR for more than 2 months during the trial, (4) patients and/or their parents requested the intervention to be stopped, (5) patients developed severe adverse events that required intervention be stopped, (6) the primary investigator or the institutional review board at each center decided to stop the trial, or (7) patients were lost to follow-up.

Patients were examined at the start of treatment, at 1, 3, and 6 months, and then every 3 months up to 24 months. Casual office blood pressure and treatment compliance were monitored. Blood was collected for creatinine, urea nitrogen, uric acid, sodium, potassium, albumin, and IgA. Early morning urine was collected for uP/Cr at each visit. After 23–27 months of treatment, all patients were scheduled to undergo second renal biopsies.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the disappearance rate of proteinuria, as defined by early morning uP/Cr < 0.2 g/g [14]. Secondary endpoints were changes in early morning uP/Cr, eGFR, and pathologic features. Adverse events that occurred during the trial were also evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed based on an intention-to-treat principle. Analysis sets of efficacy evaluation and safety evaluation were decided as the per-protocol patients and all eligible patients, respectively, determined before the start of analysis. The Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazard model were applied to time to first disappearance of proteinuria for estimation of the disappearance rate at 24 months. t test was used to compare the median of eGFR, uP/Cr, and pathologic features of the two groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare adverse events. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and JMP 13.0 software package (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

The result was evaluated by an independent data safety monitoring committee, which included a statistician and a pediatric nephrologist who did not see the patients enrolled in the present study.

Results

Patients

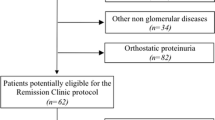

Study enrollment was terminated in January 2010 because of the paucity of eligible patients. A total of 63 children with biopsy-proven IgAN with FMP were enrolled at 19 centers in Japan (Fig. 1). Patients were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups (group A, n = 31; group B, n = 32). However, one patient in group B did not receive experimental intervention because of withdrawn consent. Five patients (group A, n = 3; group B, n = 2) were not included in the efficacy evaluation because of failure to meet inclusion criteria and by protocol violation.

Median follow-up was 749 days in group A and 743 days in group B. One patient in group A discontinued intervention treatment by withdrawal of consent at month 23. Another patient in group B discontinued because of nephrotic-range proteinuria in month 5. These two patients were included in the analysis for their time in the study.

Patient clinical and laboratory characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no important clinical and pathological differences in the characteristics between the two treatment groups.

Efficacy

The primary end point, the disappearance rate of proteinuria, is shown in Fig. 2. The primary endpoint was reached by 25 of 28 patients in group A, and 25 of 29 patients in group B by the end of 24 months after randomization. In group A, the cumulative disappearance rate of proteinuria at 24 months was 89.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 74.9 to 97.3%). In group B, it was 89% (95% CI, 74.4 to 97.2%), the difference of − 0.3% was smaller than threshold. Median duration of group B was a little shorter; 1.28 (0.73 to 2.23) times to that of group A. In a sub-analysis of the patients who showed uP/Cr > 0.5 at the start of treatment (12 patients in group A and 10 patients in group B), the primary end point was also shown in Fig. 3. There was also no significant difference in the primary endpoint in the sub-analysis (log-rank test, p = 0.088). During the 2-year protocol treatments, 10 (group A) and 14 (group B) patients showed normal urine findings (uP/Cr < 0.2 g/g and hematuria negative). There was no significant difference in the ratio of patients showing normal urine findings between both groups (log-rank test, p = 0.277).

The clinical data at the start and end in both groups and the differences in clinical change between the two groups are shown in Table 2. In both groups, hematuria was improved. The mean eGFR at the start and end of treatment were normal in both groups. No patients developed chronic renal insufficiency during the study period. In both groups, the mean uP/Cr in morning urine showed reduction at end of treatment. There was no significant difference in all clinical change between the two groups.

Renal biopsies were undergone by 26 patients in group A and 28 patients in group B during months 23–27. The pathological data at the start and end in both groups and the differences in pathological change between the two groups are shown in Table 2. The ratio of glomeruli showing mesangial proliferation and crescents was decreased in both groups. The ratio of glomeruli showing segmental sclerosis and global sclerosis was increased in both groups. There was no significant difference in all pathological change between the two groups.

Immunofluorescence was not available for the repeat biopsy at 23–27 months for three patients in group A and three patients in group B. The initial renal biopsy revealed mild or moderate mesangial deposits of IgA in all but eight patients (group A, n = 4; group B, n = 4). The mesangial IgA deposits in both groups became less intense at the end of treatment. However, they did not disappear completely in all but six patients (group A, n = 4; group B, n = 2).

As sub-analyses, factors related to proteinuria disappearance are shown in Table 3. Although E1 was a significant factor related to proteinuria disappearance in both univariate and multivariate analyses, since the number of patients showing E1 was only one each in both groups, the clinical significance of this finding was thought to be insufficient.

Safety

A summary of adverse events reported during the trial is shown in Table 4. Mild dizziness was reported by eight patients in group A and 16 patients in group B. There was no patient who showed angioedema and hyperkalemia. No patients had severe adverse events requiring hospitalization.

Combination therapy was discontinued during infection to prevent side effects in two patients in group B for 3 and 6 days, respectively. Owing to fever and elevated serum Cr, a further two patients in group B discontinued combination therapy; one patient for 7 days, the other patient discontinued only lisinopril for 5 days. Owing to dizziness, one patient in group B discontinued only losartan for 50 days. These patients all subsequently recovered and restarted protocol treatment as recommended by a physician.

Discussion

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that ACEI and ARB can reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function in patients with adult IgAN [5,6,7, 15]. Moreover, our previous pilot study showed that 2-year lisinopril monotherapy was effective and safe for children with mild IgAN showing minimal or FMP with persistent proteinuria [10]. However, no data suggests preference of ACEI over ARB or vice versa. Although combined ACEI/ARB therapy is regarded as having some theoretical benefits [16], there are few studies examining the efficacy and side effects of combination therapy using both ACEI and ARB for IgAN [8, 17]. A meta-analysis reviewing six RCTs involving 109 IgAN patients suggested that combination treatment with ACEI and ARB might provide more benefits for reducing daily proteinuria [18]. In the KDIGO clinical practice guideline for glomerulonephritis in 2012, it was said that more studies were needed to determine definite benefits of combination therapy with ACEI and ARB.

Information on efficacy and safety of 2-year treatment in 57 patients with childhood mild IgAN was limited due to the paucity of eligible patients in this study compared to the originally planned number of cases. This was the first RCT, however, to compare efficacy and safety between patients with lisinopril monotherapy and those with combination therapy of lisinopril and losartan to determine the better treatment for childhood IgAN with mild proteinuria. Our analyses could not ascertain significant differences in disappearance rate of proteinuria (primary endpoint), or changes in early morning uP/Cr, or eGFR (secondary endpoints) between the two groups. As a weakness of the study, the sample size was not reached despite the prolonged period of recruitment, which reduces its statistical power. We have to consider this fact in an evaluation of the results of this study.

In addition to the comparison of clinical findings, pathological findings before and after the 2-year treatments were compared in both groups. There was a significantly decreased percentage of glomeruli with mesangial proliferation and crescents (acute lesions) and lower intensity of glomerular mesangial IgA deposits in immunofluorescence in childhood IgAN patients in both groups. This may indicate the possibility of anti-inflammatory properties of ACEI and ARB related to RAAS blockade. On the other hand, we found a significant increase in the percentage of glomeruli with global sclerosis and extent of tubular atrophy (chronic lesions) in the patients of both groups. Although ACEI and ARB are thought to have anti-sclerotic and anti-interstitial lesion properties [19,20,21,22,23], such effects were not detected in the present study. We have to consider the possibility that since all of the included patients had normal renal function and the mean proteinuria of both groups was scarce, such a circumstance may detract from the validity of the study with the primary objective of disappearance of proteinuria, and that this circumstance may justify the absence of better results in the combination group.

In consideration of side effects, although there was no significant difference in blood pressure before and after treatments in the two groups, the number of cases with dizziness was higher in the combination treatment with ACEI and ARB than in ACEI monotherapy, despite no statistical significance.

Additionally, there is a known association of ACEI and ARB use with development of AKI during acute illnesses, such as fever and diarrhea. ACEI/ARB causes preferential vasodilation of the glomerular efferent arterioles thereby reducing glomerular filtration pressure for a given systemic blood pressure. During hypovolemia or a hypotensive state such as fever, frequent vomiting, or diarrhea, this reduction of efferent vascular tone leads to decreased glomerular filtration and potentially to AKI [24]. Recent studies [25,26,27] show that treatment with ACEI/ARB is associated with only a small increase in AKI risk. Meanwhile, continued use of ACEI/ARB during acute illness is more likely to be associated with AKI. We should therefore pay attention to the two patients who showed fever and elevated serum Cr in group B. In studies to examine the effect of RAS-blocking agents on diabetic nephropathy, there was significant proteinuria reduction benefit in the combination therapy arm, but one trial was terminated early due to AKI or severe decreased renal function events, and more patients who showed doubling of serum creatinine were found in combination therapy [28, 29].

We may have to discuss the difference between our definition of mesangial proliferative severe changes and M1 of the Oxford classification. However, since the present study started before the publication of the Oxford classification in 2009, although we did not utilize it for enrolment criteria and data analysis plan in the present study protocol, we used it in sub-analyses of pathological findings.

Some of the patients in both groups showed normal urinary findings. It is thought that perhaps prognoses of these patients are good. However, even in such patients, a careful follow-up is important considering recurrence of the disease.

In conclusion, within the limits of the final sample size, taking into consideration there being no superiority of combination therapy according to clinical and pathological findings, and considering the side effects, we propose lisinopril monotherapy as the favored treatment for childhood IgAN with mild proteinuria.

References

Donadio JV, Grande JP (2002) IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med 347:738–748

Alexopoulos E (2004) Treatment of primary IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 65:341–355

Yata N, Nakanishi K, Shima Y, Togawa H, Obana M, Sako M, Nozu K, Tanaka R, Iijima K, Yoshikawa N (2008) Improved renal survival in Japanese children with IgA nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol 23:905–912

Szeto CC, Lai FM, To KF, Wong TY, Chow KM, Choi PC, Lui SF, Li PK (2001) The natural history of immunoglobulin a nephropathy among patients with hematuria and minimal proteinuria. Am J Med 110:434–437

Coppo R, Peruzzi L, Amore A, Piccoli A, Cochat P, Stone R, Kirschstein M, Linné T (2007) IgACE: a placebo-controlled, randomized trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in children and young people with IgA nephropathy and moderate proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 18:1880–1888

Li PK, Leung CB, Chow KM, Cheng YL, Fung SK, Mak SK, Tang AW, Wong TY, Yung CY, Yung JC, Yu AW, Szeto CC, HKVIN Study Group (2006) Hong Kong study using valsartan in IgA nephropathy (HKVIN): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Kidney Dis 47:751–760

Praga M, Gutiérrez E, González E, Morales E, Hernández E (2003) Treatment of IgA nephropathy with ACE inhibitors: a randomized and controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 14:1578–1583

Russo D, Minutolo R, Pisani A, Esposito R, Signoriello G, Andreucci M, Balletta MM (2001) Coadministration of losartan and enalapril exerts additive antiproteinuric effect in IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 38:18–25

Horita Y, Tadokoro M, Taura K, Suyama N, Taguchi T, Miyazaki M, Kohno S (2004) Low-dose combination therapy with temocapril and losartan reduces proteinuria in normotensive patients with immunoglobulin a nephropathy. Hypertens Res 27:963–970

Nakanishi K, Iijima K, Ishikura K, Hataya H, Awazu M, Sako M, Honda M, Yoshikawa N, Japanese Pediatric IgA Nephropathy treatment study group (2009) Efficacy and safety of lisinopril for mild childhood IgA nephropathy: a pilot study. Pediatr Nephrol 24:845–849

Yoshikawa N, Ito H, Yoshihara S, Nakahara C, Yoshiya K, Hasegawa O, Matsuo T (1987) Clinical course of IgA nephropathy in children. J Pediatr 110:555–560

Simon R, Wittes RE, Ellenberg SS (1985) Randomized phase II clinical trials. Cancer Treat Rep 69:1375–1381

Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM (2001) A flexible design for multiple armed screening trials. Stat Med 20:1051–1060

Hogg RJ, Portman RJ, Milliner D, Lemley KV, Eddy A, Ingelfinger J (2000) Evaluation and management of proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome in children: recommendations from a pediatric nephrology panel established at the National Kidney Foundation conference on proteinuria, albuminuria, risk, assessment, detection, and elimination (PARADE). Pediatrics 105:1242–1249

Horita Y, Tadokoro M, Taura K, Ashida R, Hiu M, Taguchi T, Furusu A, Kohno S (2007) Prednisolone co-administered with losartan confers renoprotection in patients with IgA nephropathy. Ren Fail 29:441–446

Lods N, Ferrari P, Frey FJ, Kappeler A, Berthier C, Vogt B, Marti HP (2003) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition but not angiotensin II receptor blockade regulates matrix metalloproteinase activity in patients with glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 14:2861–2872

Yang Y, Ohta K, Shimizu M, Nakai A, Kasahara Y, Yachie A, Koizumi S (2005) Treatment with low-dose angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) plus angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) in pediatric patients with IgA nephropathy. Clin Nephrol 64:35–40

Cheng J, Zhang X, Tian J, Li Q, Chen J (2012) Combination therapy an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin receptor blocker for IgA nephropathy: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract 66:917–923

Ruggenenti P (2004) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II antagonism in nondiabetic chronic nephropathies. Semin Nephrol 24:158–167

Ma L, Fogo A (2001) Role of angiotensin II in glomerular injury. Semin Nephrol 21:544–553

Ibrahim HN, Rosenberg ME, Hostetter TH (1997) Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the progression of renal disease: a critical review. Semin Nephrol 17:431–440

Maschio G, Alberti D, Janin G, Locatelli F, Mann JF, Motolese M, Ponticelli C, Ritz E, Zucchelli P, The Angitensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibition in Progressive Renal Insufficiency Study Group (1996) Effect of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor benazepril on the progression of chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med 334:939–945

Fogo A, Yoshida Y, Glick AD, Homma T, Ichikawa I (1988) Serial micropuncture analysis of glomerular function in two rat models of glomerular sclerosis. J Clin Invest 82:322–330

Schoolwerth AC, Sica DA, Ballermann BJ, Wilcox CS, Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease and the Council for High Blood Pressure Research of the American Heart Association (2001) Renal considerations in angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor therapy: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease and the Council for High Blood Pressure Research of the American Heart Association. Circulation 104:1985–1991

Mansfield KE, Nitsch D, Smeeth L, Bhaskaran K, Tomlinson LA (2016) Prescription of renin-angiotensin system blockers and risk of acute kidney injury: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 6:e012690

Whiting P, Morden A, Tomlinson LA, Caskey F, Blakeman T, Tomson C, Stone T, Richards A, Savović J, Horwood J (2017) What are the risks and benefits of temporarily discontinuing medications to prevent acute kidney injury? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 7:e012674

Parr SK, Matheny ME, Abdel-Kader K, Greevy RA Jr, Bian A, Fly J, Chen G, Speroff T, Hung AM, Ikizler TA, Siew ED (2018) Acute kidney injury is a risk factor for subsequent proteinuria. Kidney Int 93:460–469

Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, Dyal L, Schumacher H, Pogue J, Wang X, Maggioni A, Budaj A, Chaithiraphan S, Dickstein K, Keltai M, Metsärinne K, Oto A, Parkhomenko A, Piegas LS, Svendsen TL, Teo KK, Yusuf S (2008) ONTARGET investigators: renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet 372:547–553

Leehey DJ, Zhang JH, Emanuele NV, Whaley-Connell A, Palevsky PM, Reilly RF, Guarino P, Fried LF; VA NEPHRON-D Study Group (2015) BP and renal outcomes in diabetic kidney disease: the veterans affairs nephropathy in diabetes trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10:2159–2169

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all of the participants and attending physicians for their contributions.

Funding

This study was supported by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants (Research on Children and Families) from the Japanese Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare, and in part by a research grant from the Kidney Foundation, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the institutional review board at each center and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written assent was obtained from patients who were old enough to understand and written informed consent was obtained from all of their parents.

Disclosures

KN received lecture fees from AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo, Co. Ltd. MH received lecture fees from Pfizer Japan Inc. and KYORIN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. KI received lecture fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Co., Ltd. and grant from Pfizer Japan Inc. SI received lecture fees from Mylan Inc., AstraZeneca, Pfizer Japan Inc., Shionogi & Co. Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo, Co. Ltd., Meiji Seika Pharma Co., and grant from Pfizer Japan Inc., Merck & Co. YO received consulting fees from Shionogi & Co. Ltd. KI received a grant from Daiichi Sankyo, Co., Ltd., lecture fees and/or consulting fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co., Ltd., NY. The other authors had no disclosure to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shima, Y., Nakanishi, K., Sako, M. et al. Lisinopril versus lisinopril and losartan for mild childhood IgA nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial (JSKDC01 study). Pediatr Nephrol 34, 837–846 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-018-4099-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-018-4099-8