Abstract

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) increases the risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) and renal scarring. Many prospective studies have evaluated the role of antimicrobial prophylaxis in the prevention of recurrent UTI and renal scarring in children with VUR. Of these, the RIVUR trial was the largest, randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind, multicenter study, involving 607 children aged 2–72 months with grade I–IV VUR and a first or second symptomatic UTI. The median age of children in the RIVUR trial was 12 months, 92 % were female, 91 % were randomized after a first UTI, 86 % had a febrile index UTI, and 71 (56 %) of 126 toilet-trained children had bladder bowel dysfunction. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole reduced the risk of UTI recurrences by 50 % (hazard ratio 0.50; 95 % confidence interval 0.34–0.74) as compared to placebo. No significant difference was seen in renal scarring between the two groups. However, this does not invalidate the role of prophylaxis in preventing renal scars because RIVUR and other recent prospective studies were not designed to address renal scarring as a primary study endpoint. In view of the RIVUR Trial and other studies that showed similar results, albeit in selected groups of patients, the debate on antimicrobial prophylaxis should shift from “no prophylaxis” to “selective prophylaxis” in children with VUR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

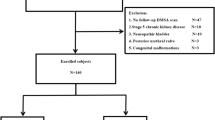

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) increases the risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) and renal scarring [1, 2]. In the last decade many prospective studies have been conducted to evaluate the role of antimicrobial prophylaxis in the prevention of recurrent UTI and renal scarring in children with VUR. This includes the RIVUR trial, which is to date the largest, randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind, multicenter study carried out in young children (age range 2–72 months) with grade I–IV VUR and a first or second febrile or symptomatic UTI. The primary outcome of the study was UTI recurrence, and the secondary outcomes included renal scarring, antibiotic resistance, and treatment failure. Pilot studies were done to guarantee consistency in methodology and imaging quality of dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) renal scans and voiding cystourethrograms (VCUG). Digital images of DMSA scans were read independently by two radiologists, and those of the VCUG/renal ultrasound scan were read by two other radiologists. Any difference of opinion was ultimately adjudicated by consensus between the two radiologists in each pair. Altogether 607 children were randomized from 19 centers with very diverse clinical settings; 302 received trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMZ) prophylaxis and 305 received exactly matching placebo [3].

Study results

The median age of the children in the RIVUR trial was 12 months, 92 % were females, 91 % were randomized after a first UTI, 86 % had a febrile index UTI, and 71, 56 % of 126 toilet-trained children had bladder bowel dysfunction (BBD). Recurrent UTI occurred in 39/302 children on prophylaxis compared with 72/305 children who received placebo [relative risk (RR) 0.55; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.38–0.78]. Prophylaxis reduced the risk of UTI recurrences by 50 % [hazard ratio (HR) 0.50; 95 % CI 0.34–0.74]. Only 37 children (8.3 %) had new renal scars during the study period—8.2 % of those on prophylaxis versus 8.4 % of those on placebo [absolute risk difference 95 % CI 0.19 (−4.9 to 5.3)]. No significant difference was seen in stool Escherichia coli resistance, but the first symptomatic UTI recurrence with resistant E. coli was significantly more likely to occur among those on prophylaxis (63 %) than on those on placebo (19 %) [absolute risk difference 95 % CI −44.0 (−64.1 to −24.0); p = <0.001] [4].

Discussion

The most recent prospective studies that have evaluated the efficacy of antimicrobial prophylaxis in children with VUR are summarized in Table 1. Some of these studies, including the one by Garin et al. [5], showed no significant difference in recurrence of UTI with antimicrobial prophylaxis [5–7], whereas others, including the RIVUR trial [4], showed that prophylaxis significantly lowered risk of UTI in some children with VUR [8–10]. Roussey-Kesler et al. [10] reported a significant decrease in UTI recurrence in boys, particularly those with grade III VUR, which was the highest grade included in the study. The authors of the PRIVENT study [8] reported a 52 % decreased risk of UTI (RR of active to placebo 0.66; 95 % CI 0.35–1.23) with prophylaxis in patients with VUR. The Swedish reflux trial reported a significantly lower risk of febrile UTI recurrence with prophylaxis in girls with grade III–IV VUR than in those on surveillance (p = 0.0002). In the RIVUR study [4], the HR for UTI recurrences consistently favored prophylaxis, irrespective of sex, age at entry, degree of VUR, first versus second UTIs before enrolment, TMP/SMZ-resistant pathogen causing index UTI, and status of VUR during the study period. Children with baseline BBD, as well as those with a febrile index infection, derived particular benefit, with reductions in recurrence of 80 and 60 %, respectively [4].

Renal scarring was a secondary endpoint for the RIVUR trial, and no significant difference was noted with antimicrobial prophylaxis. Similar observations have been reported by the authors of other studies. However, this does not invalidate the role of prophylaxis in preventing renal scars because none of these studies, including the RIVUR trial, were sufficiently powered to evaluate differences in renal scarring. Furthermore, the scarring outcome in the RIVUR trial could have been affected by multiple factors, including a prompt diagnosis and treatment of UTI recurrence in study children, exclusion of those with more than two infections, and the duration of follow-up. Appropriately designed studies with longer follow-up are needed to evaluate the role of antimicrobial prophylaxis in the prevention of renal scarring.

A high rate of uropathogen resistance to the antimicrobial being used for prophylaxis has been previously reported; however, such a resistance pattern was not noted in stool specimens of the children enrolled in the RIVUR trial. Also in the RIVUR trial, the index UTI caused by TMP/SMZ-resistant uropathogen did affect the benefit of antimicrobial prophylaxis.

RIVUR and other recent studies

Comparison of the results of the RIVUR study with those of other recent studies can be misleading because of significant qualitative differences among the studies. The RIVUR trial had the largest sample size with two- to sixfold more patients than the other studies in children with VUR. Only PRIVENT and RIVUR were placebo-controlled, double-blind trials, and these trials also had the most rigorous patient inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the RIVUR, older children, including teenagers, and children with asymptomatic UTI were excluded, as were children with no pyuria. Urine in non-toilet-trained children was collected by uretheral catheterization only. Pilot studies were done to have consistency in methodology and interpretation of VCUG and DMSA scans. The limitations of other prospective studies, cited by Cara-Fuentes et al [11]. in their editorial commentary, have been highlighted in many publications. These include a 2011 Cochrane analysis which reported considerable heterogeneity (design or reporting limitations) in the analysis of these studies, with only one study adequately blinded [12]. A recently published systematic review on the role of antimicrobial prophylaxis in children with VUR evaluated 1,547 studies, eight of which were included in the meta-analysis [13]. Of these eight studies, only PRIVENT and RIVUR studies were graded as having a low risk of bias, with the remaining six studies [5, 9, 10, 14–16] deemed to be at a high risk of performance and detection bias. The meta-analysis revealed that prophylaxis is effective in preventing recurrence of UTI and that the effect is more pronounced in the two studies with a low risk of bias.

RIVUR and the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines

In 2011, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection published its clinical practice guidelines for the management of first febrile UTI in children aged 2–24 months. Its recommendation against routine antimicrobial prophylaxis in young children after first febrile UTI was based on data collected mainly from studies with a high risk of bias [5–7, 10]. The bias and other flaws in these studies are not mitigated by the AAP Subcommittee limiting its analysis of data to infants aged only up to 24 months in their respective patient populations.

The authors of these guidelines acknowledge the importance of the RIVUR trial and a possible need to review guidelines once the study results are published. Soon after publication of the RIVUR trial, the AAP Subcommittee reaffirmed the applicability of its guidelines (www.aapnews.org; July 2014, page 5) based on the assertions that VUR does not “appear” to be a major cause of renal damage, active treatment of VUR “seems” not to reduce the occurrence of chronic kidney disease, prophylaxis for infants and young children does not “appear” to reduce renal scarring, and the benefit of prophylaxis “appears” to be a quite “modest” in delaying/preventing recurrence of UTI. However, it is difficult for any clinician to translate these passive assertions into a blanket advice against prophylaxis while counseling a parent of an infant with VUR, particularly since RIVUR and other studies have shown a significant decrease in UTI recurrence with prophylaxis in children with VUR.

The RIVUR trial was not designed to validate the role of VCUG after first UTI because all children in the trial had VUR, which was a trial inclusion criterion. However, in view of the RIVUR trial and other study results, it seems prudent to diagnose VUR after the first UTI in selected children so that the risk of UTI recurrence can be reduced with prophylaxis. A need for VCUG in a selected group of patients with first febrile UTI is also supported by the American Urological Association [2, 17] and the European Association of Urology (http://www.uroweb.org/guidelines/online-guidelines). The Executive Committee, Section on Urology (AAP) has expressed significant reservations about the AAP recommendation against routine VCUG after a first febrile UTI. It stated that the guidelines are based on studies that collected urine in non-toilet-trained children by bag specimens in spite of the guidelines emphasizing the importance of the urine collection method, did not include circumcision status or evaluation of BBD, lacked statistical power, and did not evaluate compliance with medication; in addition, DMSA scans were not done in all studies. The Executive Committee concluded that “the recommendation is based on a flawed interpretation of limited data” and “these conclusions are premature and represent a misinterpretation of the data presented,” adding further that the VCUG should remain an accepted option after a febrile UTI in selected children [17]. The potential risks of not doing VCUG after a UTI were highlighted in a study that evaluated the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) imaging guidelines against a historic cohort of 934 patients with UTI. Of these patients, 105 had abnormal renal imaging findings and only 44 (42 %) would have been diagnosed by using NICE criteria. Of the remaining 61 (58.1 %) patients, 32 (52.5 %) had significant urological anomalies including at least Grade III VUR and or renal scarring that would have been missed [18].

RIVUR and statistical issues in the editorial commentary

The Cara-Fuentes et al. [11] editorial commentary includes a post hoc redefining of outcomes and misrepresentations of the statistical concepts and results reported in the RIVUR trial. The RIVUR trial was designed with first post-randomization UTI as the primary outcome. Participants were followed to ascertain additional UTIs to determine those meeting a secondary outcome of treatment failure.

Analysis of our primary outcome by considering exactly one post-randomization recurrent UTI, ignoring those patients with more than one recurrent UTI and thereby combining those with two or more UTIs together with those children who had no recurrent UTI, as suggested in the commentary, is an illogical and uninterpretable statistical comparison. The authors go on to separately consider those children who had three or four post-randomization UTIs (N = 5 in the prophylaxis group and N = 8 in the placebo group, a difference of 3 patients). While this may be a clinically relevant outcome, it is not the outcome that RIVUR and most studies of recurrent UTI have used. Indeed, we know of no published trial with three or more recurrent UTIs as a pre-specified outcome. Therefore, to assert that the RIVUR Investigators recommend “starting routine long term urinary antibiotic prophylaxis in 302 patients to benefit only three patients” is inaccurate and misleading.

While Cara-Fuentes et al. [11] are entitled to believe that a 50 % reduction of the risk of recurrent UTI with prophylaxis (or doubling of the risk of recurrent UTI with placebo) is a “slight benefit,” it is not correct to assume this occurred when “almost half of the children did not have VUR.” While it is correct that VUR had resolved in half of the 428 children who had a VCUG performed at 2 years post-randomization, it is not known when the VUR resolved and whether it resolved before or after any recurrent UTI occurred.

In their discussion of “time to first recurrent UTI,”, Cara-Fuentes et al. [11] focus on “the 10 % difference between the two groups as expected” and “10 % threshold of significance” in a statistically naïve transference of assumptions that were made in the original RIVUR power assumptions to evaluate the level of statistical significance of the trial results. As described in the RIVUR protocol (available online through the New England Journal of Medicine materials accompanying the full article [4], a priori power analyses were performed using varied assumptions for the expected event rates in the placebo and prophylaxis groups, as well as rates for non-compliance and attrition. The purpose of these power analyses was to identify an appropriate sample size to address the primary hypothesis. In our report, we always acknowledged that subgroup analyses, such as those discussed by Cara-Fuentes et al. [11], would be under-powered except for marked differences; that is, the sample size in the RIVUR study might be insufficient to detect important treatment group differences in the subgroup analyses. In particular, insufficient power would be expected for the subgroups depicted in Figure S2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material appendix to the RIVUR results paper [4] (restricted to children younger than 2 years of age and subgrouped by VUR grade such that each subgroup was comprised of <95 children). Interpretation of the RIVUR subgroup analyses must acknowledge the sample size limitations. Therefore, it is incorrect to conclude that “no benefit was observed in what has been considered a high risk group, such as young children with VUR grade III and IV.” Non-statisticians must be reminded frequently that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

Lastly, we did not include a comparator group of children without VUR to investigate whether VUR increases the risk of UTI because it would be unethical to randomize children without VUR to antimicrobial prophylaxis. Absence of VUR was a study exclusion criterion. However, a RIVUR ancillary study “Careful Urinary Tract Infection Evaluation (CUTIE)” has been completed and does provide a comparator group of children without VUR who followed identical UTI definitions and study procedures of the RIVUR study. Results of the CUTIE study and analyses of joint RIVUR and CUTIE data will be published in the near future.

Conclusion

The RIVUR trial was not designed to evaluate the AAP guidelines. The trial was initiated 5 years before and completed 2 years after the guidelines were published. It showed a 50 % reduction in recurrences of UTI for children receiving antibiotic prophylaxis. The results of RIVUR and other studies that showed similar results, albeit in selected groups of patients, cannot be ignored. We cannot overlook the significant limitations with most of the studies included in the AAP meta-analysis for its guidelines on antimicrobial prophylaxis and VCUG after first UTI in young children. We also must not pass the onus for preventing morbidity of UTI recurrence and potential renal injury to parents because of the challenges associated with clinical presentation and diagnosis of UTI in infants and young children. As clinicians, we bear the responsibility to share evidence-based results with parents who have the right to make a choice about what is best for their children. We also need to keep in mind the limitations of renal imaging, including renal ultrasound, VCUG and DMSA renal scan. In view of the RIVUR trial results, the debate on antimicrobial prophylaxis should shift from “no prophylaxis” to “selective prophylaxis” in children with VUR.

References

Shaikh N, Ewing AL, Bhatnagar S, Hoberman A (2010) Risk of renal scarring in children with a first urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Pediatrics 126:1084–1091

Peters CA, Skoog SJ, Arant BS Jr, Copp HL, Elder JS, Hudson RG, Khoury AE, Lorenzo AJ, Pohl HG, Shapiro E, Snodgrass WT, Diaz M (2010) Summary of the AUA guideline on management of primary vesicoureteral reflux in children. J Urol 184:1134–1144

Carpenter MA, Hoberman A, Mattoo TK, Mathews R, Keren R, Chesney RW, Moxey-Mims M, Greenfield SP, Trial Investigators RIVUR (2013) The RIVUR trial: profile and baseline clinical associations of children with vesicoureteral reflux. Pediatrics 132:e34–45

Trial Investigators RIVUR, Hoberman A, Greenfield SP, Mattoo TK, Keren R, Mathews R, Pohl HG, Kropp BP, Skoog SJ, Nelson CP, Moxey-Mims M, Chesney RW, Carpenter MA (2014) Antimicrobial prophylaxis for children with vesicoureteral reflux. N Engl J Med 370:2367–2376

Garin EH, Olavarria F, Garcia Nieto V, Valenciano B, Campos A, Young L (2006) Clinical significance of primary vesicoureteral reflux and urinary antibiotic prophylaxis after acute pyelonephritis: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Pediatrics 117:626–632

Montini G, Rigon L, Zucchetta P, Fregonese F, Toffolo A, Gobber D, Cecchin D, Pavanello L, Molinari PP, Maschio F, Zanchetta S, Cassar W, Casadio L, Crivellaro C, Fortunati P, Corsini A, Calderan A, Comacchio S, Tommasi L, Hewitt IK, Da Dalt L, Zacchello G, Dall’Amico R, IRIS Group (2008) Prophylaxis after first febrile urinary tract infection in children? A multicenter, randomized, controlled, noninferiority trial. Pediatrics 122:1064–1071

Pennesi MTL, Peratoner L, Bordugo A, Cattaneo A, Ronfani L, Minisini S, Ventura A, North East Italy Prophylaxis in VUR study group (2008) Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 121:e1489–e1494

Craig JC, Simpson JM, Williams GJ, Lowe A, Reynolds GJ, McTaggart SJ, Hodson EM, Carapetis JR, Cranswick NE, Smith G, Irwig LM, Caldwell PH, Hamilton S, Roy LP, Prevention of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection in Children with Vesicoureteric Reflux and Normal Renal Tracts (PRIVENT) Investigators (2009) Antibiotic prophylaxis and recurrent urinary tract infection in children. N Engl J Med 361:1748–1759

Brandstrom P, Esbjorner E, Herthelius M, Swerkersson S, Jodal U, Hansson S (2010) The Swedish reflux trial in children: III. Urinary tract infection pattern. J Urol 184:286–291

Roussey-Kesler G, Gadjos V, Idres N, Horen B, Ichay L, Leclair MD, Raymond F, Grellier A, Hazart I, de Parscau L, Salomon R, Champion G, Leroy V, Guigonis V, Siret D, Palcoux JB, Taque S, Lemoigne A, Nguyen JM, Guyot C (2008) Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children with low grade vesicoureteral reflux: results from a prospective randomized study. J Urol 179:674–679, discussion 679

Cara-Fuentes G, Gupta N, Garin EH (2014) The RIVUR study: A review of its findings. Pediatr Nephrol doi:10.1007/s00467-014-3021-2

Nagler EV, Williams G, Hodson EM, Craig JC (2011) Interventions for primary vesicoureteric reflux. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD001532

Wang HH, Gbadegesin RA, Foreman JW, Nagaraj SK, Wigfall DR, Wiener JS, Routh JC (2014) Efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2014.08.112

Montini G, Hewitt I (2009) Urinary tract infections: to prophylaxis or not to prophylaxis? Pediatr Nephrol 24:1605–1609

Pennesi M, Travan L, Peratoner L, Bordugo A, Cattaneo A, Ronfani L, Minisini S, Ventura A, North East Italy Prophylaxis in VUR study group (2008) Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 121:e1489–1494

Craig JC, Roy LP, Sureshkumar P, Burke J, Powell H, Hodson EM (2002) Long-term antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infection in children with isolated vesicoureteric reflux (a placebo-controlled randomized trial). J Am Soc Nephrol 13:3A

Wan J, Skoog SJ, Hulbert WC, Casale AJ, Greenfield SP, Cheng EY, Peters CA, Executive Committee, Section on Urology, American Academy of Pediatrics (2012) Section on Urology response to new Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of UTI. Pediatrics 129:e1051–1053

McDonald K, Kenney I (2014) Paediatric urinary tract infections: a retrospective application of the National Institute of Clinical Excellence guidelines to a large general practitioner referred historical cohort. Pediatr Radiol 44:1085–1092

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help of Lisa Gravens-Muller from Data Coordinating Central Anel, Lauren C. Robinson from Le Bonheur Children's Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mattoo, T.K., Carpenter, M.A., Moxey-Mims, M. et al. The RIVUR trial: a factual interpretation of our data. Pediatr Nephrol 30, 707–712 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-014-3022-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-014-3022-1