Abstract

Background

Minimally Invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer is associated with less morbidity compared to open approach. Whether robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy (RAMIE) results in better long-term survival compared with open esophagectomy (OE) and minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) is unclear.

Methods

We analyzed data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) for patients with primary esophageal cancers who underwent esophagectomy in 2010–2017. Those with unknown staging, distant metastasis, or diagnosed with another cancer were excluded. Patients were stratified by RAMIE, MIE, and OE operative techniques. The Kaplan–Meier method and associated log-rank test were employed to compare unadjusted survival outcomes by surgical technique, our primary outcome. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model was employed to discern factors independently contributing to survival.

Results

A total of 5170 patients who underwent esophagectomy were included in the analysis; 428 underwent RAMIE, 1417 underwent MIE, and 3325 underwent OE. Overall median survival was 42 months. In comparison to RAMIE, there was an increased risk of death for those that underwent either MIE [Hazard Ratio (HR) = 1.19; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): > 1.00 to 1.41; P < 0.047)] or OE (HR = 1.22; 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.43; P < 0.017). Academic vs community program facility type was associated with decreased risk of death (HR = 0.84; 95% CI: 0.76 to 0.93; P < 0.001). In general, males from areas of lower income with advanced stages of cancer who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation were at increased risk of death. Factors that were not associated with survival included race and ethnicity, Charlson-Devo Score, type of health insurance, zipcode level education, and population density.

Conclusions

Overall survival was significantly longer in patients with esophageal cancers that underwent RAMIE in comparison to either MIE or OE in a 7-year NCDB cohort study.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths and is amongst the cancers with increasing incidence in Western countries [1]. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma alone represent over 95% of all esophageal cancers [2, 3]. The overall 5 year survival rate with esophageal cancer remains low at 10–15% [1, 4, 5]. The survival rate increases by 3–5 times with curative surgical resection; hence surgery is the treatment of choice for resectable disease [6,7,8,9]. Several factors including centralization of care at high-volume centers, increasing use of multimodality treatment (neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment) along with curative surgery have been implicated in improved outcomes for esophageal cancer [10,11,12,13].

Recently, emphasis has been placed on improving outcomes after esophagectomy. Of the surgical options, minimally invasive surgical techniques (MIS) confer the expected reduction in perioperative morbidity associated with esophagectomy compared to OE in both short term and at 3–5 years [10, 11, 14]. Of the MIS techniques, RAMIE has shown superior oncologic margin resection without jeopardizing perioperative or short term survival outcomes in NCDB data analysis when compared to MIE and OE [14,15,16]. However, long-term oncological outcomes after RAMIE haven’t been well reported. The objective of our current analysis is to study the long-term (> 5 years) outcomes following RAMIE and to compare them with MIE and OE in a national cancer database.

Materials and methods

In this study, we analyzed patient’s data from the NCDB database. This database is a joint endeavor of the American Cancer Society and the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons (CoC) established in 1989 and captures de-identified hospital-based data encompassing 72% of all newly diagnosed malignancies in the US annually from CoC-accredited cancer programs. The NCDB participant user file (PUF) was utilized to identify a cohort of adult patients diagnosed with esophageal cancer.

Procedures and quality control

Inclusion criteria were having been diagnosed with stage 0-III primary esophageal cancers ranging from proximal esophagus to the gastro-esophageal junction (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition—ICD-O-3—codes C15.1-C15.9) that were histologically confirmed to be squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinomas (ICD-O-3 codes 805–808 and 814–838, respectively), having undergone treatments that include esophagectomy (partial or total), esophagectomy with partial gastrectomy, or esophagectomy with unspecified gastrectomy between the year 2010 and 2017. The former is the year when surgical approach was specified in the database whereas the latter includes the last recorded vital status.

Exclusion criteria were unknown staging (clinical or pathological), esophagectomy with laryngectomy or total gastrectomy, those diagnosed with another cancer [i.e., only one reported cancer diagnosis (Sequence Number 00) to avoid confounding outcomes with patients who may have been diagnosed and treated for a separate malignancy], and those with esophageal cancers with evidence of distant metastases (stage IV) whose presence is confirmed either by radiographic or histologic means. This study analyzed de-identified data and was approved by the Creighton University Institutional Review Board (IRB).

The esophagectomy techniques were stratified by RAMIE, MIE, and OE. Neither intention-to-treat nor per-protocol analyses were performed due to relatively small proportion of cross-over between groups. Patient demographics were categorized by mean age at time of diagnosis; great-circle distance in miles between patient’s residence and site where they had surgery; days between time of diagnosis to systemic therapy, radiation, or surgery; number of regional lymph nodes examined; tumor size; male or female biological sex; Charlson/Devo comorbidity index with scores of 0,1, 2, or ≥ 3 (excluding the esophageal cancer diagnosis); Caucasian or non-Caucasian; metropolitan or urban or rural residential area; median household income (< $38,000, > $38,000–< $48,000, > $48,000–< $63,000, or > $63,000); level of educational achievements (proportion of adult with non-high school graduation per zip code); tumor’s lymph vascular invasion status and grades; receipt of neoadjuvant therapy [chemotherapy (single or multiple agents administered before surgery date) or chemoradiation (receiving cumulative dose of ≥ 4000 cGy within ≤ 199 days to surgery)] or upfront surgery; facility type where the surgery was performed (community, academic, or comprehensive programs); tumor location (thoracic esophagus, NOS (not otherwise specified), proximal third of thoracic esophagus, middle third of thoracic esophagus, distal third of thoracic esophagus, abdominal esophagus (NOS), overlapping esophagus, or esophagus, NOS); and types of insurance held (private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, non-insured status or other types of insurance, or unknown status).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of continuous variables were calculated as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range given potential skewness. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and proportion. Comparisons were made post-stratification by surgical approach with ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis given skewness. Univariate and multivariable analyses were performed to discern factors independently contributing to survival by employing a Cox proportional hazards regression model. Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed to compare the overall median survival outcomes by surgical technique, with log-rank testing. Vital status by the median overall survival was used for mortality analysis. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed utilizing SAS® 9.4 software.

Results

Characteristics of the patients

The stratification of patient that underwent esophagectomy by surgical technique is described in Fig. 1. NCDB database contained 14,884 patients diagnosed with either squamous cell carcinoma (14.9%) or adenocarcinoma (85.1%) of the esophagus or gastro-esophageal that underwent esophagectomy with a known esophagectomy approach between the year 2010 and 2017. 9714 patients were excluded because of unknown staging, another cancer diagnosis, metastatic cancer or had missing information about any of the clinical or demographic variables included in our statistical modeling. Thus, 5170 patients who underwent esophagectomy had known vital statuses and were included in the analysis—428 (8.3%) undergone RAMIE, 1417 (27.4%) MIE, and 3325 (64.3%) OE.

The demographic and baseline clinical characteristics (Table 1) did not significantly differ between the three groups except for the great-circle distance in miles between patient’s residence and site where they had surgery, days between time of diagnosis to definitive surgical procedure, rural–urban classification, and facility type. However, Fig. 2 demonstrates that the median lymph nodes harvested and examined are statistically higher for RAMIE in comparison to either MIE or OE.

Outcomes

After adjusting for age, biological sex, race and ethnicity, analytic stage, type of insurance, level of education and median household income by zip code, population density, neoadjuvant treatments, Charlson-Deyo Score, and facility center type, we found that there was an increased risk of death for those that underwent either MIE (HR = 1.19; 95% CI: > 1.00 to 1.41; P < 0.047) or OE (HR = 1.22; 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.43; P < 0.017) in comparison to RAMIE. Academic program facility type was associated with decreased risk of death compared to community program (HR = 0.84; 95% CI: 0.76 to 0.93; P < 0.001). In general, males from areas of lower income with advanced stages of cancer who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation were at increased risk of death. Our results did not show any survival impact from social factors like race and ethnicity, Charlson-Deyo Score, type of health insurance, level of education by zip code, and population density (Table 2).

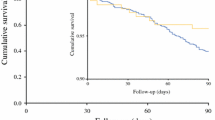

Overall survival

Amongst the 5170 patients who underwent esophagectomy for esophageal cancer from 2010 in the NCDB, 2643 (51%) were not associated with mortality status as of 2017. Among those patients that survived (not associated with mortality), 61.9% survived in the RAMIE group compared to 53.5% and 48.7% in the MIE and OE groups, respectively. Overall median survival was 42 months. The Kaplan–Meier curves (Fig. 3) demonstrates survival of the patients stratified by their respective surgical techniques.

Discussions

Multimodality treatment has been increasingly used in locally advanced esophageal cancer along with the surgical treatment. Esophagectomy has been the standard surgical treatment of choice in the past two decades. The morbidity after esophagectomy has been steadily decreasing with improvements in the preoperative and postoperative management. However, overall, 5-year survival for esophageal cancer has been consistently under 20% [1, 4, 5]. Our analysis of the National Cancer Database data showed that the median overall survival for patients who underwent esophagectomy for esophageal cancer between 2010 and 2017 was 42 months (about 3 and a half years). Our multivariate analysis showed RAMIE has significantly better long-term survival compared to other esophagectomy techniques. Other variables independently associated with better survival include undergoing esophagectomy at academic medical centers, female biological sex, receipt of neoadjuvant therapy, and patients with high median income. This study is the only long-term survival outcome analysis that was conducted in a large population database study.

Robotic surgery has been increasingly used to perform complex multi-quadrant surgical procedures like esophagectomy. Initial RCT’s comparing OE was not powered to show any difference in 3-year survival between OE and RAMIE (TIME Study) [17]. However, it revealed significantly better pulmonary complications for RAMIE group compared to OE. Later study comparing MIRO with hybrid technique and showed at 3-year follow-up reported that the HMIE group had an overall survival of 67% compared with 54.8% for OE [10]. This trial also reported that hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy was associated with a 77% lower risk of major intraoperative and postoperative complications than open esophagectomy. Furthermore, minimally invasive surgery was associated with a 50% lower risk of major pulmonary complications than open surgery. Although NCBD database does not have procedure related complications but provides longitudinal overall mortality related outcomes. Our database study provides the first longitudinal outcomes report which shows robotic approach is associated with lower mortality compared to open and minimally invasive approaches. Minimally invasive approaches are shown to be associated with less morbidity compared to open approach but the long-term survival benefits have not been reported by the above studies. MIE and RAMIE have shown to be associated with similar morbidity and our results support that RAMIE has better long-term survival.

Robotic approach has not been widely available for the patients. The patients likely to undergo robotic-assisted esophagectomy choose facilities located about two to five miles closer to their home residency in comparison to those undergoing non-robotic procedure. Their surgeries were also delayed by 9 days longer from time of diagnosis to surgery when compared with their counterparts. These two metrics indicate that urban area residents likely have better access to the robotic surgeries compared to the rural areas, where patients undergo predominantly non-robotic surgeries. Risk of death amongst facilities performing procedures positively favored academic centers compared to either community or comprehensive programs. The risk of mortality increased with disease progression to advanced stages and for males from areas of lower income who received chemotherapy or radiation regardless of the surgical techniques. Finally, we found that health determinant factors such as race and ethnicity, Charlson-Devo Score, type of health insurance, zipcode level education, and population density were not independently associated with survival of esophageal cancer following esophagectomy. These results might be at odds with some prior reports regarding the impact of socio-economic factors on esophageal cancer survival following esophagectomy [18, 19]. However, our study might not have appropriate numbers in the socio-economic zones to show any significant impact on survival.

Esophageal cancer prognosis is dependent on several factors including patient’s ability to receive multimodality treatment, early diagnosis and treatment, and receiving definitive treatments at higher volume centers [14,15,16,17]. Studies reported that centers with high volume (> 12 esophagectomies) have better outcomes compared to the low volume centers [20, 21]. Our study compared community cancer programs whose annual volume consists of more than 100 but fewer than 500 new diagnosed cancers to both comprehensive community and academic programs whose facility accession independently stands above 500 newly diagnosed cancers annually [22] and questions the notion of how volume from centers with a dozen cases [16] affect overall outcomes. Although it is apparent that higher volume has consistently shown better outcomes, it is unknown from our study whether the volume in academic centers were behind the better survival. The better survival in academic centers could be multifactorial including volume, training and overall resources, and access to the multimodality treatment and supportive care options. Our report also suggest that academic centers have better access to robotic surgery for the patient with esophageal cancer. Patients’ selection or self-selection at different facilities should be further investigated. Delaying esophagectomy for 8–12 weeks post neoadjuvant chemoradiation has previously been reported to not affect survival outcomes [23]; however, it’s unclear if there is a relationship between robotic esophagectomy patients delaying their surgical treatment and their inherent survival fitness. Overall, esophageal cancer patients who underwent robotic esophagectomy had overall better survival. Several factors including higher income, academic centers, and access to the neoadjuvant/adjuvant treatments and better lymph nodes retrieval might be possible reasons behind better survival with RAMIE.

Although national-level databases like NCDB have unique potential to produce large sample sizes to make reasonable conclusions, they are not without limitations such as the retrospective nature of the analysis, not having disease specific mortality, and immediate complications with certain categories. We also excluded esophagectomy with laryngectomy or total gastrectomy, unknown staging, and metastatic disease to understand the impact overall mortality associated with the most common subtype of esophageal cáncer for which esophagectomy is mostly performed [24]. The income measurements are based on zipcode and not based on the individual basis and have been categorized into quartiles instead of being provided within a continuous context. However, our analysis provides a large sample database study which can be associated with reasonable numbers to derive any meaningful conclusions which can have significant impact on clinical practice.

In summary, overall survival was significantly longer in patients with esophageal cancers that underwent RAMIE in comparison to either MIE or OE in a 7-year NCDB cohort study. Patients who underwent esophagectomy at academic medical centers, were biologically female, received neoadjuvant therapy, or are from high income areas were associated with better survival.

References

Then EO, Lopez M, Saleem S, Gayam V, Sunkara T, Culliford A et al (2020) Esophageal cancer: an updated surveillance epidemiology and end results database analysis. World J Oncol 11(2):55–64

Rustgi AK, El-Serag HB (2014) Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med 371(26):2499–2509

Abbas G, Krasna M (2017) Overview of esophageal cancer. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 6(2):131–136

Mariette C, Dahan L, Mornex F, Maillard E, Thomas PA, Meunier B et al (2014) Surgery alone versus chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for stage I and II esophageal cancer: final analysis of randomized controlled phase III trial FFCD 9901. J Clin Oncol 32(23):2416–2422

Huang FL, Yu SJ (2018) Esophageal cancer: risk factors, genetic association, and treatment. Asian J Surg 41(3):210–215

Iriarte F, Su S, Petrov RV, Bakhos CT, Abbas AE (2021) Surgical management of early esophageal cancer. Surg Clin North Am 101(3):427–441

Lordick F, Mariette C, Haustermans K, Obermannova R, Arnold D, Committee EG (2016) Oesophageal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 27(suppl 5):v50–v57

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: National Cancer Institute, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/esoph.html

Chen MF, Chen PT, Lu MS, Lee CP, Chen WC (2017) Survival benefit of surgery to patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 7:46139

Mariette C, Markar SR, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Meunier B, Pezet D, Collet D et al (2019) Hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 380(2):152–162

Makowiec F, Baier P, Kulemann B, Marjanovic G, Bronsert P, Zirlik K et al (2013) Improved long-term survival after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: influence of epidemiologic shift and neoadjuvant therapy. J Gastrointest Surg 17(7):1193–1201

van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP et al (2012) Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 366(22):2074–2084

Biebl M, Andreou A, Chopra S, Denecke C, Pratschke J (2018) Upper gastrointestinal surgery: robotic surgery versus laparoscopic procedures for esophageal malignancy. Visc Med 34(1):10–15

Maramara PB, Shridhar R, Huston J, Meredith K (eds) (2020) Outcomes associated with robotic esophagectomy: an NCDB analysis. Academic surgical congress. Orlando, FL, American College of Surgeons

Mederos MA, de Virgilio MJ, Shenoy R, Ye L, Toste PA, Mak SS et al (2021) Comparison of clinical outcomes of robot-assisted, video-assisted, and open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 4(11):e2129228

Hue JJ, Bachman KC, Worrell SG, Gray KE, Linden PA, Towe CW (2021) Outcomes of robotic esophagectomies for esophageal cancer by hospital volume: an analysis of the national cancer database. Surg Endosc 35(7):3802–3810

Straatman J, van der Wielen N, Cuesta MA, Daams F, Roig Garcia J, Bonavina L et al (2017) Minimally invasive versus open esophageal resection: three-year follow-up of the previously reported randomized controlled trial: the time trial. Ann Surg 266(2):232–236

Erhunmwunsee L, Gulack BC, Rushing C, Niedzwiecki D, Berry MF, Hartwig MG (2017) Socioeconomic status, not race, is associated with reduced survival in esophagectomy patients. Ann Thorac Surg 104(1):234–244

Tran PN, Taylor TH, Klempner SJ, Zell JA (2017) The impact of gender, race, socioeconomic status, and treatment on outcomes in esophageal cancer: A population-based analysis. J Carcinog 16:3

Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL (2003) Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 349(22):2117–2127

Clark JM, Boffa DJ, Meguid RA, Brown LM, Cooke DT (2019) Regionalization of esophagectomy: where are we now? J Thorac Dis 11(Suppl 12):S1633–S1642

About Cancer Program Categories: American College of Surgeon: Commission on Cancer, 2022 [cited 2022. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/accreditation/categories

Kim JY, Correa AM, Vaporciyan AA, Roth JA, Mehran RJ, Walsh GL et al (2012) Does the timing of esophagectomy after chemoradiation affect outcome? Ann Thorac Surg 93(1):207–212

Daly JM, Fry WA, Little AG, Winchester DP, McKee RF, Stewart AK et al (2000) Esophageal cancer: results of an American College of Surgeons Patient Care Evaluation Study. J Am Coll Surg 190(5):562–572

Simard EP, Ward EM, Siegel R, Jemal A (2012) Cancers with increasing incidence trends in the United States: 1999 through 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 62(2):118–128

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Innocent Byiringiro, Sarah Aurit, and Kalyana Nandipati has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Byiringiro, I., Aurit, S.J. & Nandipati, K.C. Long-term survival outcomes associated with robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy (RAMIE) for esophageal cancer. Surg Endosc 37, 4018–4027 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09588-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09588-x