Abstract

Background

There is a lack of published data on variations in practices concerning laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The purpose of this study was to capture variations in practices on a range of preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative aspects of this procedure.

Methods

A 45-item electronic survey was designed to capture global variations in practices concerning laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and disseminated through professional surgical and training organisations and social media.

Results

638 surgeons from 70 countries completed the survey. Pre-operatively only 5.6% routinely perform an endoscopy to rule out peptic ulcer disease. In the presence of preoperatively diagnosed common bile duct (CBD) stones, 85.4% (n = 545) of the surgeons would recommend an Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-Pancreatography (ERCP) before surgery, while only 10.8% (n = 69) of the surgeons would perform a CBD exploration with cholecystectomy. In patients presenting with gallstone pancreatitis, 61.2% (n = 389) of the surgeons perform cholecystectomy during the same admission once pancreatitis has settled down. Approximately, 57% (n = 363) would always administer prophylactic antibiotics and 70% (n = 444) do not routinely use pharmacological DVT prophylaxis preoperatively.

Open juxta umbilical is the preferred method of pneumoperitoneum for most patients used by 64.6% of surgeons (n = 410) but in patients with advanced obesity (BMI > 35 kg/m2, only 42% (n = 268) would use this technique and only 32% (n = 203) would use this technique if the patient has had a previous laparotomy. Most surgeons (57.7%; n = 369) prefer blunt ports. Liga clips and Hem-o-loks® were used by 66% (n = 419) and 30% (n = 186) surgeons respectively for controlling cystic duct and (n = 477) 75% and (n = 125) 20% respectively for controlling cystic artery. Almost all (97.4%) surgeons felt it was important or very important to remove stones from Hartmann’s pouch if the surgeon is unable to perform a total cholecystectomy.

Conclusions

This study highlights significant variations in practices concerning various aspects of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The first laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed in the world in 1985 [1]. Since then, there have been many changes and developments in practices concerning this procedure. Technological advancements have played a key role in the evolution of laparoscopic cholecystectomy over the last three decades [2].

It is now one of the commonest surgical procedures performed worldwide, with approximately 66,000 procedures performed annually in the United Kingdom alone [3]. Despite this, there is a lack of agreement amongst surgeons on its various aspects [4, 5]. These variations in practices may account for the differences in key outcome measures, such as the morbidity rates, mortality rates, re-intervention rates, and readmission rates in different parts of the world [6, 7]. Any variation in practice is also an opportunity to identify the best practice through focussed studies.

There are studies formally evaluating global variations in practices on a range of surgical procedures [8, 9]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study in the scientific literature capturing global variations in practices concerning laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This may have adversely impacted our ability to determine best practices concerning this procedure and standardise clinical pathways and surgical steps. Knowing the full range of variations in practices is often the first step toward determining the practice associated with the best outcomes. Knowledge of all the variations in practices may also be potentially useful in medicolegal cases especially if the practice of the surgeon is different from that of the “experts”.

We, therefore, designed a global survey to understand variations in a range of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative practices concerning laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Materials and methods

We designed a 45-item survey on www.planetsurvey.com. Survey questions and options were suggested by all the authors and finalised after several rounds of internal discussions and pilot testing. Responses to each question included most of the common options authors were aware of. We further provided an option to submit “other” variations that we were potentially not aware of for each question.

The survey link was freely shared by authors within their personal network, through Twitter® and on groups of general surgeons on Facebook®, LinkedIn®, and Google®, and through mailing lists of professional societies such as The Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons (TUGS), Association of Laparoscopic Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (ALSGBI), and Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons (AUGIS). The survey was made live on 10th February 2021 and closed for analysis on 7th May 2021.

Any healthcare professional performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, irrespective of their country of practice or grade was invited to participate in the survey. Those who do not perform laparoscopic cholecystectomy were asked to leave the survey. No identifiable information was collected, and no attempt was made to identify individual responses. Standard descriptive statistics were used.

Some of the terms used in this study may be more commonly used in the United Kingdom and therefore merit further clarification. For example, “hot gall bladder” means acute presentation with a condition that would generally merit an emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy; “swift list” means dedicated emergency access to operating theatres for patients needing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for a “hot gall bladder”, and “separate Upper GI rota” means availability of surgeons to carry out laparoscopic cholecystectomy on an emergency basis. Typically, these are upper gastrointestinal surgeons.

Results

Characteristics of participating surgeons

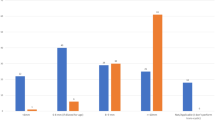

A total of 638 healthcare professionals from 70 countries took the survey. Of these, 28.4% (n = 179) respondents were from the United Kingdom, followed by India (n = 80, 12.7%), Egypt (50, 7.9%) and Italy (n = 24, 3.8%). Figure 1 provides the regional distribution of the respondents. Of these, 54.3% (n = 373) respondents had provision for theatre access for emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy in their hospitals. At the same time, 72.8% (n = 464) of respondents mentioned that they did not have surgeons available to carry out emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy in their institution.

Preoperative practices

Table 1 lists all the responses to preoperative practices. Ultrasound scan (US) was the preferred diagnostic modality for patients with biliary colic for 96.7% (n = 617) of the respondents. Most (n = 546, 85.6%) of the respondents would only perform preoperative Oesophago-Gastro-Duodenoscopy (OGD) to rule out Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) if the patient has atypical symptoms.

For acute cholecystitis, Ultrasound Scan (US) was the diagnostic modality of choice according to 87.1% (n = 556) of the respondents. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was the preferred modality for calculous obstructive jaundice (n = 423, 66.3%). In the presence of preoperatively diagnosed common bile duct (CBD) stones, 85.4% (n = 545) of the surgeons would recommend an Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-Pancreatography (ERCP) before surgery, while 10.8% (n = 69) of the surgeons would perform a CBD exploration with cholecystectomy. Similarly, for asymptomatic choledocholithiasis diagnosed on an intraoperative cholangiogram, most (n = 208; 32.6%) would perform a cholecystectomy followed by an ERCP.

In patients presenting with gallstone pancreatitis, 61.2% (n = 389) of the surgeons perform cholecystectomy during the same admission once pancreatitis has settled down. Most (79%; n = 325) would use a combination of clinical status and inflammatory markers to determine the resolution of pancreatitis.

Intraoperative and postoperative practices

All intraoperative and postoperative variations in practices are listed in Table 2. Over half of the respondents (57%; n = 363) always recommended prophylactic antibiotics. Others had specific indications for this such as empyema of the gallbladder (54%; n = 243), major spillage of gall bladder content (41%; n = 185), and even minor spillage (36.8%; n = 166). Cefuroxime (n = 236, 37.2%) and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Co-amoxiclav) (n = 229, 36.1%) were the most commonly used antibiotics in the absence of penicillin allergy. In case of mild penicillin allergy Cefuroxime (n = 286, 45.8%) and Teicoplanin (n = 105, 16.8%) were commonly used. (It should be noted that administration of cephalosporins in such cases is not contraindicated as the cross-reactivity is only 1%). Regarding deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis, most of the respondents (n = 444, 69.7%) do not routinely use pharmacological DVT prophylaxis before surgery or induction.

Open juxta umbilical (infra, supra, or trans) was the most preferred method for creating pneumoperitoneum (n = 410, 64.6%). Fewer respondents (n = 268, 42%) would however use this approach in patients with BMI > 35 kg/m2. Blunt tip disposable (n = 221, 34.7%) and reusable ports (n = 148, 23.2%) were the most used types. Bladed ports were only used by 17.6% of the respondents (n = 112).

Dissection of the Calot’s triangle was predominantly done using hook diathermy by most of the surgeons (n = 374, 58.8%), and 34.3% of surgeons (n = 218) preferred blunt dissection using a laparoscopic dissector. Most surgeons (57.7%; n = 369) prefer blunt ports. Liga clips and Hem-o-loks® were used by 66% (n = 419) and 30% (n = 186) surgeons respectively for controlling cystic duct and (n = 477) 75% and (n = 125) 20% respectively for controlling cystic artery. The most common approach to difficult Calot’s triangle was retrograde dissection from the fundus (49.2%, n = 312). In cases of CBD injury detected intraoperatively, one-third of surgeons (n = 214) would repair the injury themselves.

Qualitative analysis of free-text answers

Table 3 describes the thematic qualitative analysis of free-text answers for preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative practices.

Discussion

This survey is the first global study capturing variations in practices concerning laparoscopic cholecystectomy. With 638 surgeons from 70 countries worldwide, we believe we have captured a representative sample and are unlikely to have missed any common variation. This knowledge will enable future work to determine best practices in the performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

With the growing evidence favouring early intervention after acute presentations of gallstone disease [10,11,12,13], many practice guidelines have recommended establishing emergency cholecystectomy pathways for early cholecystectomy for patients presenting acutely with symptomatic gall bladder disease [14, 15]. This survey shows that emergency access to operating theatres for this purpose was not available in the institution of approximately a third of the respondents. Similarly, two-thirds of the respondents mentioned that they did not have the availability of emergency surgeons who could perform these operations in their hospitals. These figures are sobering statistics regarding the management of a common general surgical emergency.

The current Association of Upper GI Surgeons (AUGIS) guidelines in the United Kingdom [15] recommend liver function tests and the abdominal US as primary investigations for suspected biliary colic. In this survey, most respondents (617) report their preference for the US as an initial diagnostic modality for biliary colic. For acute cholecystitis, 87% favour the use of US, while 10.5% prefer CT scans. Tokyo guidelines [16] recommend the US as the first-choice imaging method for diagnosing acute cholecystitis due to its widespread availability, ease of use, lack of radiation, and cost-effectiveness. However, the diagnosis of gallstone disease can be challenging when the patients present with atypical symptoms that can mimic peptic ulcer disease or gastritis. That is why some surgeons routinely recommend OGD to rule out these conditions before planning gallbladder surgery [17]. However, this survey shows that such surgeons are in a minority with only 36/638 (5.6%) surgeons recommending a routine OGD before surgery.

When asked about the best modality for investigating patients presenting with obstructive jaundice, unsurprisingly the majority (66.3%; 423/638) preferred an MRCP, which is known to be more sensitive for the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis than a US or CT scan [18]. For patients with CBD stones, a single-stage cholecystectomy and surgical bile duct clearance is feasible, cost-effective, and may even be associated with a shorter hospital stay compared to a two-stage ERCP and cholecystectomy approach [14]. Yet it is not the preferred approach of most of the surgeons who took this survey with a clear majority (545/637; 85.6%) preferring staged management with ERCP followed by cholecystectomy. This could be due to a relative lack of expertise needed to explore CBD laparoscopically and/or non-availability of equipment. Regarding the time interval from CBD clearance to cholecystectomy, there was again a huge variation in practice. This probably reflects a lack of clear evidence to guide practice in this area [19,20,21,22].

Three hundred eighty-nine surgeons (61%) reported that they would perform cholecystectomy in the index admission after resolution of gallstone pancreatitis, and 82 (12.9%) would do so within two weeks. Early gallbladder removal after biliary pancreatitis is associated with fewer 30-day readmissions [10], shorter hospital stay [11], fewer gallstone-related events, and lower ERCP usage [23]. It is, therefore, interesting that some surgeons are not yet able to offer this to their patients.

The incidence of surgical site infection after gallbladder surgery has been reported to be higher with open cholecystectomy compared to keyhole surgery, ranging from 0.3% to 3.4% for the latter and 1.1% to 8.4% for the former [24, 25]. However, currently available evidence does not support routine prophylactic antibiotics for cholecystectomy [26]. Vohra et al. reported that antibiotic prophylaxis significantly reduced the rates of superficial SSI and all-cause complications but resulted in similar rates of deep SSI, readmissions, and re-interventions. Additionally, the number needed to treat to prevent one superficial SSI was 45. They concluded that antibiotics appear effective at reducing SSI after non-emergency cholecystectomy. However, due to the high number needed to treat, it is unclear whether they add a meaningful clinical benefit [27].

A meta-analysis that included 5259 patients [28] showed that antibiotics did not significantly reduce the risk of SSI or overall nosocomial infections. Another double-blinded randomised controlled trial [29] studied the effect of piperacillin/tazobactam (PAP) vs Placebo in acute cholecystitis; the study showed that the postoperative infectious complications (PIC) rate were significantly higher in patients with a raised CRP at randomisation and on the day of surgery and in cases of conversion to an open procedure. Most of the surgeons in this survey use prophylactic antibiotics routinely, despite what one may interpret as a rather limited evidence base in its support.

Gallstone disease is an established risk factor for thromboembolic events [30] The recent NICE guidelines released in 2018 [31] recommend offering VTE prophylaxis to patients undergoing abdominal surgery who are at an increased risk of VTE, starting mechanical VTE prophylaxis on admission until the person no longer has significantly reduced mobility relative to their normal or anticipated mobility, and adding pharmacological VTE prophylaxis for a minimum of 7 days for people undergoing abdominal surgery whose risk of VTE outweighs their risk of bleeding. Interestingly, 69.7%, 45.9%, and 69.4% of the surgeons who took this survey do not routinely offer pharmacological DVT prophylaxis before surgery, elastic compression stockings, or intermittent compression devices, respectively. These may be regarded as alarming figures and perhaps suggest a need for higher quality evidence in this area.

Regarding pneumoperitoneum creation, most of the surgeons preferred the open juxta umbilical technique with more inclination towards the closed technique in patients with obesity. Previous abdominal surgery is associated with increased operative time and adhesions; however, it does not compromise the safety of performing gallbladder surgery. [32] The currently available evidence does not favour one technique over the other for achieving pneumoperitoneum. In this survey, 37.7% (n = 240) of the surgeons use a closed technique in patients with previous abdominal surgery.

Most surgeons preferred to use Liga clips over Hem-o-Loks® when controlling the cystic artery and cystic duct. Unfortunately, there is no study in the literature comparing the two techniques. Studies have also investigated the clipless technique and reported satisfactory outcomes [33, 34].

There is significant variation in practice in the event of an intraoperatively detected bile duct injury. The latest guidelines of the world society of emergency surgery [35] on the surgical management of intraoperatively diagnosed bile duct injury (BDIs) recommend the selective use of adjuncts for biliary tract visualisation (e.g., IOC, ICG-C) during difficult cholecystectomies or whenever BDI is suspected to increase the rate of intraoperative diagnosis and to consider the opinion of another surgeon. They also recommend direct repair with or without T-tube placement in cases of minor BDIs, and hepaticojejunostomy as the treatment of choice in those with major BDIs. Similar recommendations have been proposed by Brunt ML et al. based on their recent survey directed by a steering group and subject experts from well-known surgical societies [36, 37].

When surgeons were asked whether they would use a retrieval bag to retrieve the dissected gallbladder from the abdomen, only about 70% said they would use one. A recent meta-analysis showed no difference in wound infection with the use of a retrieval bag. However, the evidence used was of a low level, so it remains debatable. But most surgeons prefer to use them [38]. Furthermore, only about 69% (n = 428/617) of those who used the retrieval bags confirmed that it was in their operating count. About 61% would retrieve the gallbladder through the umbilical port site, and 37% would retrieve it from the epigastric port. A meta-analysis has shown that retrieval of the gallbladder through the juxta-umbilical port site is associated with less postoperative pain and less retrieval time intraoperatively [39].

Multimodal analgesia is an integral part of the enhanced recovery pathways after abdominal and gastrointestinal surgery. The current evidence suggests the effectiveness of local anaesthetic wound infiltration [40,41,42]. This study showed variation in practice in this area. Moreover, the majority do not use a local anaesthetic in the gallbladder bed/intra-abdominally. Vijayaraghavalu et al. found that intraperitoneal bupivacaine resulted in a significant reduction in postoperative pain for the first six hours after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, prolonged the time taken to request rescue analgesia, and lessened shoulder pain significantly [43].

Most of the surgeons (86.8%, n = 551/635) in this study do not routinely place a drain. This is probably because there is no evidence to support the use of routine drainage after non-complicated cholecystectomy [44]. Half of the surgeons (n = 319) who participated in this survey would discharge their patients the next day, while around 44% would discharge them on the same day. Day case procedures are of significant financial and psychological benefits, are feasible, and don’t compromise patient safety [45]. Around 65% of our participants would still offer a follow-up appointment for their patients.

Strengths and weaknesses

This is the first global study reporting on variations in a range of pre, peri, and postoperative practices concerning laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Its global reach and large sample size further suggest that we have captured all common variations. Authors would recommend caution in interpreting commonest variations as best practices as determining best practices for each of these areas is likely to need focussed studies.

At the same time, one can only place limited value on such a set of self-reported data. Choices selected may vary depending on the respondents’ engagement with the survey tool, item similarity, and familiarity with the English language. Moreover, we have simply presented the proportions without attempting any complex statistical analyses because the purpose of this study was to understand all the variations in practice rather than carry out a detailed subset analysis for a number of factors. Finally, due to limited numbers from different countries, we have not been able to compare practices according to countries or regions. Our findings need confirmation in future studies.

Conclusion

This survey is the first study in scientific literature capturing variations in preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative practices concerning Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. It should pave way for future studies aimed at determining best practices amongst those in use.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study can be released upon request.

References

Reynolds W Jr (2001) The first laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS 5:89–94

Hasbahceci M (2016) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: what has changed over the last three decades? Clin Surg 1:1166

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Health and Social Care Directorate (2015) Quality Standards and Indicators Briefing Paper. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs104/documents/gallstone-disease-qs-briefing-paper2 Last Accessed 25/07/2021.

Macano C, Griffiths EA, Vohra RS (2017) Current practice of antibiotic prophylaxis during elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2017.0001

Donnellan E, Coulter J, Mathew C, Choynowski M, Flanagan L, Bucholc M, Johnston A, Sugrue M (2020) A meta-analysis of the use of intraoperative cholangiography; time to revisit our approach to cholecystectomy? Surg Open Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sopen.2020.07.004

McIntyre C, Johnston A, Foley D, Lawler J, Bucholc M, Flanagan L, Sugrue M (2020) Readmission to hospital following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. https://doi.org/10.5114/ait.2020.92967

Omar I, Hafez A (2021) Readmissions after cholecystectomy in a tertiary UK centre: incidence, causes and burden. J Minim Access Surg. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmas.JMAS_296_20

Adil MT, Aminian A, Bhasker AG, Rajan R, Corcelles R, Zerrweck C, Graham Y, Mahawar K (2020) Perioperative practices concerning sleeve gastrectomy—a survey of 863 surgeons with a cumulative experience of 520,230 procedures. Obes Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04195-7

Rosado EG, Olivella G, Natal-Albelo EJ, Echegaray GJ, Rivera LL, Guevara CA, Alejandro LM, Martínez-Rivera A, Ramírez N, Foy CA (2020) Practice variation among Hispanic American orthopedic surgeons in the management of geriatric distal radius fracture. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1177/2151459320969378

Garg SK, Bazerbachi F, Sarvepalli S, Majumder S, Vege SS (2019) Why are we performing fewer cholecystectomies for mild acute biliary pancreatitis? Trends and predictors of cholecystectomy from the National Readmissions Database (2010–2014). Gastroenterol Report. https://doi.org/10.1093/gastro/goz037

Davoodabadi A, Beigmohammadi E, Gilasi H, Arj A, Taheri Nassaj H (2020) Optimising cholecystectomy time in moderate acute biliary pancreatitis: a randomised clinical trial study. Heliyon. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03388

Takahashi N, Umemura A, Suto T, Fujiwara H, Ariyoshi Y, Nitta H, Takahara T, Hasegawa Y, Sasaki A (2021) Aggressive laparoscopic cholecystectomy in accordance with the Tokyo guideline 2018. JSLS. https://doi.org/10.4293/JSLS.2020.00116

Blohm M, Österberg J, Sandblom G, Lundell L, Hedberg M, Enochsson L (2016) The sooner, the better? The importance of optimal timing of cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis: data from the national Swedish registry for gallstone surgery, GallRiks (2017). J Gastrointest Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-016-3223-y

Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Endo I, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Pitt HA, Umezawa A, Asai K, Han HS, Hwang TL, Mori Y, Yoon YS, Huang WS, Belli G, Dervenis C, Yokoe M, Kiriyama S, Itoi T, Jagannath P, Garden OJ, Miura F, Nakamura M, Horiguchi A, Wakabayashi G, Cherqui D, de Santibañes E, Shikata S, Noguchi Y, Ukai T, Higuchi R, Wada K, Honda G, Supe AN, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Gouma DJ, Deziel DJ, Liau KH, Chen MF, Shibao K, Liu KH, Su CH, Chan ACW, Yoon DS, Choi IS, Jonas E, Chen XP, Fan ST, Ker CG, Giménez ME, Kitano S, Inomata M, Hirata K, Inui K, Sumiyama Y, Yamamoto M (2018) Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.516

AUGIS (2013). Commissioning guide: Gallstone disease. Available from: https://www.augis.org/wp content/uploads/2014/05/ Gallstone disease commissioning guide for REPUBLICATION 1. pdf. (Last Accessed 2021 3 July).

Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Wakabayashi G, Kozaka K, Endo I, Deziel DJ, Miura F, Okamoto K, Hwang TL, Huang WS, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Noguchi Y, Shikata S, Ukai T, Higuchi R, Gabata T, Mori Y, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Jagannath P, Jonas E, Liau KH, Dervenis C, Gouma DJ, Cherqui D, Belli G, Garden OJ, Giménez ME, de Santibañes E, Suzuki K, Umezawa A, Supe AN, Pitt HA, Singh H, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Teoh AYB, Honda G, Sugioka A, Asai K, Gomi H, Itoi T, Kiriyama S, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Matsumura N, Tokumura H, Kitano S, Hirata K, Inui K, Sumiyama Y, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines (2018) Diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos) (2018). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.515

Kunnuru SKR, Kanmaniyan B, Thiyagarajan M, Singh BK, Navrathan N (2021) A study on Efficacy of UGI Scopy in Cholelithiasis patients before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Minim Invasive Surg. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8849032

Kang KA, Kwon HJ, Ham SY, Park HJ, Shin JH, Lee SR, Kim MS (2020) Impacts on outcomes and management of preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in patients scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: for whom it should be considered? Ann Surg Treat Res. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2020.99.4.221

Gao MJ, Jiang ZL (2021) Effects of the timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography on liver, bile, and inflammatory indices and cholecysto-choledocholithiasis patient prognoses. Clinics (Sao Paulo). https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2021/e2189

Wang CC, Tsai MC, Wang YT, Yang TW, Chen HY, Sung WW, Huang SM, Tseng MH, Lin CC (2019) Role of cholecystectomy in choledocholithiasis patients underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Sci Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38428-z

Abdalkoddus M, Franklyn J, Ibrahim R, Yao L, Zainudin N, Aroori S (2021) Delayed cholecystectomy following endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography is not associated with worse surgical outcomes. Surg Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08593-w

Xu J, Yang C (2020) Cholecystectomy outcomes after endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with choledocholithiasis: a meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01376-y

Zhong FP, Wang K, Tan XQ, Nie J, Huang WF, Wang XF (2019) The optimal timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000017429

Milosevic M, Plecko V, Kalenic S, Fiolic Z, Vanek M (2013) Surveillance of surgical site infection after cholecystectomy using the hospital in Europe link for infection control through surveillance protocol. Surg Infect (Larchmt). https://doi.org/10.1089/sur.2012.096

Warren DK, Nickel KB, Wallace AE, Mines D, Tian F, Symons WJ, Fraser VJ, Olsen MA (2017) Risk factors for surgical site infection after cholecystectomy. Open Forum Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofx036

Yang JD, Yu HC (2021) Prospective control study of clinical effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy on infection rate. Yonsei Med J. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2021.62.2.172

Vohra RS, Hodson J, Pasquali S, Griffiths EA, CholeS study group, West Midlands research collaborative (2017) Effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in non-emergency cholecystectomy using data from a population-based cohort study. World J Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4018-3

Pasquali S, Boal M, Griffiths EA, Alderson D, Vohra RS, CholeS Study Group, West Midlands Research Collaborative (2015) Meta-analysis of perioperative antibiotics in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9904

Jaafar G, Sandblom G, Lundell L, Hammarqvist F (2020) Antibiotic prophylaxis in acute cholecystectomy revisited: results of a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Langenbecks Arch Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-020-01977-x

Chen CH, Lin CL, Kao CH (2020) The risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with gallstones. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082930

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018). Venous thromboembolism in over 16s: reducing the risk of hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng89/resources/venous-thromboembolism-in-over-16s-reducing-the-risk-of-hospitalacquired-deep-vein-thrombosis-or-pulmonary-embolism-pdf-1837703092165 Last Accessed 03/08/2021. Last Accessed 03/08/2021

Katar MK, Ersoy PE (2021) Is previous upper abdominal surgery a contraindication for laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.14272

Abounozha S, Alshahri T, Alammari S, Ibrahim R (2021) Clipless laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a better technique in reducing intraoperative bleeding. Ann Med Surg (Lond). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.01.039

Abounozha S, Ibrahim R, Alshahri T (2021) Is the rate of bile leak higher in clipless laparoscopic cholecystectomy compared to conventional cholecystectomy? Ann Med Surg (Lond). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.01.038

de’Angelis N, Catena F, Memeo R, Coccolini F, Martínez-Pérez A, Romeo OM, De Simone B, Di Saverio S, Brustia R, Rhaiem R, Piardi T, Conticchio M, Marchegiani F, Beghdadi N, Abu-Zidan FM, Alikhanov R, Allard MA, Allievi N, Amaddeo G, Ansaloni L, Andersson R, Andolfi E, Azfar M, Bala M, Benkabbou A, Ben-Ishay O, Bianchi G, Biffl WL, Brunetti F, Carra MC, Casanova D, Celentano V, Ceresoli M, Chiara O, Cimbanassi S, Bini R, Coimbra R, Luigi de’Angelis G, Decembrino F, De Palma A, de Reuver PR, Domingo C, Cotsoglou C, Ferrero A, Fraga GP, Gaiani F, Gheza F, Gurrado A, Harrison E, Henriquez A, Hofmeyr S, Iadarola R, Kashuk JL, Kianmanesh R, Kirkpatrick AW, Kluger Y, Landi F, Langella S, Lapointe R, Le Roy B, Luciani A, Machado F, Maggi U, Maier RV, Mefire AC, Hiramatsu K, Ordoñez C, Patrizi F, Planells M, Peitzman AB, Pekolj J, Perdigao F, Pereira BM, Pessaux P, Pisano M, Puyana JC, Rizoli S, Portigliotti L, Romito R, Sakakushev B, Sanei B, Scatton O, Serradilla-Martin M, Schneck AS, Sissoko ML, Sobhani I, Ten Broek RP, Testini M, Valinas R, Veloudis G, Vitali GC, Weber D, Zorcolo L, Giuliante F, Gavriilidis P, Fuks D, Sommacale D (2021) 2020 WSES guidelines for the detection and management of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. World J Emerg Surg. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-021-00369-w

Brunt LM, Deziel DJ, Telem DA, Strasberg SM, Aggarwal R, Asbun H, Bonjer J, McDonald M, Alseidi A, Ujiki M, Riall TS, Hammill C, Moulton CA, Pucher PH, Parks RW, Ansari MT, Connor S, Dirks RC, Anderson B, Altieri MS, Tsamalaidze L, Stefanidis D, and the Prevention of Bile Duct Injury Consensus Work Group (2020) Safe cholecystectomy multi-society practice guideline and state of the art consensus conference on prevention of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003791

Michael Brunt L, Deziel DJ, Telem DA, Strasberg SM, Aggarwal R, Asbun H, Bonjer J, McDonald M, Alseidi A, Ujiki M, Riall TS, Hammill C, Moulton CA, Pucher PH, Parks RW, Ansari MT, Connor S, Dirks RC, Anderson B, Altieri MS, Tsamalaidze L, Stefanidis D, Prevention of Bile Duct Injury Consensus Work Group (2020) Safe cholecystectomy multi-society practice guideline and state-of-the-art consensus conference on prevention of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07568-7

La Regina D, Mongelli F, Cafarotti S, Saporito A, Ceppi M, Di Giuseppe M, di Tor F, Vajana A (2018) Use of retrieval bag in the prevention of wound infection in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: is it evidence-based? A meta-analysis. BMC Surg. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-018-0442-z,19Nov

Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Clark MC, Barratt OA, Taktak S, Subar D, Henley N (2019) Retrieval of gallbladder via umbilical versus epigastric port site during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLE.0000000000000662.PMID:31033631

Gelman D, Gelmanas A, Urbanaitė D, Tamošiūnas R, Sadauskas S, Bilskienė D, Naudžiūnas A, Širvinskas E, Benetis R, Macas A (2018) Role of multimodal analgesia in the evolving enhanced recovery after surgery pathways. Medicina. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina54020020

Omar I, Abualsel A (2019) Efficacy of Intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine after bariatric surgery: randomized controlled trial. Obes Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03775-x

Liang M, Chen Y, Zhu W, Zhou D (2020) Efficacy and safety of different doses of ropivacaine for laparoscopy-assisted infiltration analgesia in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomised control trial. Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022540

Vijayaraghavalu S, Bharthi Sekar E (2021) A Comparative study on the postoperative analgesic effects of the intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine versus normal saline following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.14151

Yang J, Liu Y, Yan P, Tian H, Jing W, Si M, Yang K, Guo T (2020) Comparison of laparoscopic cholecystectomy with and without abdominal drainage in patients with non-complicated benign gallbladder disease: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000020070

Chandio A, Khatoon Z, Chandio K, Naqvi SM, Naqvi SA (2017) Immediate outcome of day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Trends Transplant 2:2017. https://doi.org/10.15761/TiT.1000226

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

No funding was received for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK and KB: Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal analysis, original draft preparation. IO: Formal analysis, Discussion of The Results and Literature Review, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. KM: Conceptualisation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. MT: Conceptualisation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. All authors have seen the final manuscript and approved it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Mr. Matta Kuzman, Mr. Khalid Munir Bhatti, Mr. Islam Omar, Mr. Hany Khalil, Dr. Wah Yang, Mr. Prem Thambi, Mr. Nader Helmy, Mr Amir Botros, Dr. Thomas Kidd, Ms. Siobhan McKay, Mr. Altaf Awan, Prof Mark Taylor, and Prof. Kamal Mahawar have declared no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed Consent does not apply.

Institutional research committee approval number

No prior Institutional or ethical approval was deemed necessary for this type of survey.

Research involving human and/or animal rights

Not Applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuzman, M., Bhatti, K.M., Omar, I. et al. Solve study: a study to capture global variations in practices concerning laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 36, 9032–9045 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09367-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09367-8