Abstract

Background

Compared with open herniorrhaphy, laparoscopic herniorrhaphy can yield more favorable clinical outcomes. However, previous studies failed to give definite answer for comparison between laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair approaches. This study aimed to systematically determine the differences in recurrence rate, duration of return to work, pain, surgery duration, and duration of hospital stay between transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) approach for inguinal hernia.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library (including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) abstracts up to September 2017 were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing TAPP or TEP hernia repairing. The hernia recurrence rate, time to return to work, analgesic consumption, surgery duration, hospital stay, and the pain score were recorded with subgroup analysis of the hernia type.

Results

Sixteen RCTs that randomized 1519 patients with hernia into TEP and TAPP repair groups were analyzed in this study. The results revealed that TEP repair resulted in shorter hospital stay of primary cases (MD − 0.87, 95% CI − 1.67 to − 0.07) but was associated with a longer operative duration in recurrent hernia group (MD 3.35, 95% CI 0.16 − 6.54).

Conclusions

TEP and TAPP have their own advantages. TEP repair reduces short-term postoperative pain more effectively than TAPP repair and results in shorter hospital stay of primary cases. In contrast, TAPP repair is correlated with shorter surgery duration. These findings show that shared decision-making regarding both approaches of laparoscopic hernia repair may be needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy was first reported in the early 1990s and has been practiced for decades [1]. The recurrence rate of hernia repair has been a major concern; however, it has decreased because of the standardization of surgical techniques and the development of an artificial mesh [2, 3]. Studies have reported that compared with open herniorrhaphy, laparoscopic herniorrhaphy might be associated with shorter recovery time, lower postoperative pain scores, and fewer complications [2]. Moreover, recent studies have compared the effects of different laparoscopic approaches for hernia repair [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. These studies not only determined the recurrence rate but also pain scores, hospital stay, and time to return to work.

The first two systematic reviews on this topic were published in 2005 in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Hernia, respectively [11, 12]. These studies systematically reviewed hernia repair, but they included case series, concurrent comparison studies, and only one randomized controlled trial (RCT) with a small sample size. Because of the limited evidence, these systematic reviews have suggested conducting more adequately powered RCTs. In recent decades, many RCTs have compared laparoscopic hernia repair approaches, particularly transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) techniques. These studies tried to determine which laparoscopic approach can repair inguinal hernia more effective than the other. Yet, those studies could not consistently conclude the clinical outcomes of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair.

Another recent systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs reported no significant differences in recurrence rate, time to return to work, hospital stay, and total complications between TAPP and TEP in repairing inguinal hernia [13]. This study made a stronger conclusion than previous studies. The conclusion declared no differences in clinical outcomes and complications between TEP and TAPP. Unfortunately, the systematic review did not completely identify the current evidence. For one, 2 RCTs that were published before 2014 were not mentioned in the review. For another, 4 RCTs were published after the study. Moreover, this systematic review did not take hernia types into consideration. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to synthesize the current evidences by using more comprehensive search strategy and analysis for determination of the differences in recurrence rate, duration of return to work, pain, surgery duration, and duration of hospital stay between the two approaches in repairing inguinal hernia.

Methods

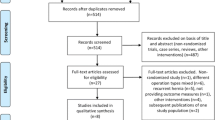

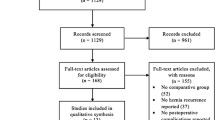

A flowchart of study selection in this systematic review and meta-analysis is presented according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines [14]. Because this study analyzed published data, it was exempted from institutional review board approval, and its protocol is published online in PROSPERO (CRD42017068992).

Search and study selection

This systematic review systematically searched the Cochrane library, Embase, and PubMed to identify the relevant research articles comparing the TEP and TAPP approaches in treating patients with inguinal hernia. These systematic literature searches used the following keywords: “groin hernias,” “inguinal hernias,” “hernia inguinalis,” “groin hernia,” “inguinal hernia,” “total extra peritoneal,” “total extraperitoneal,” “TEP,” “transabdominal preperitoneal,” “transabdominal preperitoneal,” and “TAPP.” These keywords were searched in free text words and medical subject headings (MeSH in PubMed and Emtree in Embase) with Boolean algebras. All the systematic literature searches were conducted to identify articles published without language or publication date restrictions. The final search was completed by two authors at 13th September 2017 (Supplementary Material 1).

All obtained citation records were screened by two authors (Chen and Kang). Any screening-related disagreement was resolved by discussion with the third author (Wu). Titles and abstracts were screened according to the following inclusion criteria: (i) patients with hernia and (ii) those who underwent laparoscopic repair. The exclusion criteria for further screening were as follows: (i) no comparison between the TEP and TAPP approaches, (ii) not an RCT, (iii) conference reports, and (iv) irrelevant documents.

Quality assessment of included studies

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. This appraisal tool assesses selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting biases. The tool contains six items: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, participant and personnel blinding, assessment blinding, incomplete outcome data, and selective bias reporting. All included RCTs were assessed by two reviewers who individually evaluated the quality of RCTs. Any disagreements were discussed with and resolved by the third author.

Data extraction and analysis

Two authors extracted and examined the data independently; they identified and verified data on the recurrence rate, time to return to work, analgesic consumption, surgery duration, hospital stay, and pain scores for pooling analysis. If the article reported the mean and standard error (SE), the standard deviation (SD) was estimated based on the sample size (SE = SD/√N). If the study presented the median with the minimum and maximum values, the mean and SD were estimated from the sample size, median, and range [15].

The results were expressed as risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous data. Peto odds ratio (OR) was used for dichotomous data showing a zero cell. The mean difference (MD) of original studies was calculated to compare continuous variables that were measured by using the same tool between the TEP and TAPP approaches. All meta-analyses used a random-effects model with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and I2. The value for I2 can present the percentage of total variability across the studies in a meta-analysis. Thus, this study examined heterogeneity among the pooled studies by using I2. Regarding to value of I2, 25, 50, and 75% of I2 were defined as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [16]. In all analyses, p < .05 was considered statistically significant. The results were expressed as forest plots that were generated by using RevMan version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Center, Cochrane Collaboration) for Microsoft Windows in all analyses.

This systematic review further analyzed effects in different hernia types and assessed publication bias. Subgroup analyses of the hernia type (primary and recurrent hernia data) were conducted to clarify the effects in different hernia types. The Egger’s regression intercept, Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation, and the fail–safe N test were conducted for assessing publication bias [17].

Results

Literature search and selection

The search yielded 608 studies from PubMed (n = 212), from Embase (n = 337), Cochrane Library (n = 56), and from reference lists or other sources (n = 3). This systematic review excluded 204 duplicated studies. According to the exclusion criteria, 361 studies were excluded after title and abstract screening. In the phase of full-text screening, 12 conference reports, 10 systematic review, 2 non-RCTs, and 2 guidelines were excluded. Therefore, this systematic review included 17 citation records from 16 RCTs [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Figure 1 shows the processes of study identification and selection.

Characteristics of included studies

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 16 RCTs that randomized 1519 patients into TEP and TAPP repair groups [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] Table 1 showing the characteristics of the included studies, namely study location, sample size, included years, patient age, patient sex, hernia type and location, pain score instruments, normal activity measurements, follow-up duration, and surgeon experience. These trials were conducted in the United States (n = 1) [19], Austria (n = 2) [3, 23], China (n = 3) [7, 24, 25], Egypt (n = 1) [8], Greece (n = 1) [6], India (n = 5) [4, 10, 18, 21, 22], and Turkey (n = 3) [5, 9, 20] since 1989–2016. Further information was performed in Supplementary Material 2.

The overall quality of the included studies was acceptable. The risk of selection, detection, attrition, and reporting biases was < 80% in all the RCTs; only the risk of performance bias exceeded 75% (Supplementary Material 3).

Primary outcomes

Eight of the included studies with 778 patients reported no significant differences in the recurrence rate between TEP and TAPP repair (Peto OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.34–1.63, p > .05; I2 = 0%) [3, 4, 6, 8, 19,20,21, 23]. Sensitivity analysis showed that this result was not changed when any included RCT was removed from the meta-analysis (Supplementary Material 4, S4.1). After stratification by hernia types, no significant differences were observed between TEP and TAPP repair in the primary hernia subgroup (Peto OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.26–2.43, p > .05) as well in primary plus recurrence hernia data (Peto OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.23–2.09, p > .05). Both subgroups showed low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%; Fig. 2A).

Six trials reported the effects of laparoscopic approaches on time to return to work after inguinal hernia repair [4, 6, 8, 10, 21, 23]. Data from another study were not included in the meta-analysis because of the lack of a clear definition of “the time to resumption of normal activities” [7]. A meta-analysis including 586 patients reported no significant differences in time to return to work between TEP and TAPP repair (MD 0.01, 95% CI − 1.19 to 1.12; p > .05; I2 = 57%). This result was still no significant in sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Material 4, S4.2). In the primary hernia subgroup, no significant differences were reported between the 2 groups (MD 0.97, 95% CI − 1.53 to 1.73, p > .05; I2 = 72%). The subgroup of primary plus recurrent hernia data also showed no significant differences (MD − 0.39; 95% CI − 2.08 to 1.30, p > .05; Fig. 2B).

Five RCTs reported the requirement for extra post-operative analgesia in 55 (20%) of 275 patients who underwent TEP repair and 64 (19.34%) of 331 patients who underwent TAPP repair, with a Peto OR of 0.92 (95% CI 0.61–1.39; p > .05; I2 = 88%) [3,4,5, 9, 23]. After stratification by hernia types, the TEP repair group required less analgesia compared with the TAPP repair group in primary hernia data alone (Peto OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.30–0.84, p = .009). In the subgroup including recurrence hernia data, the TAPP repair group required significantly less analgesia compared with the TEP repair group (Peto OR 2.71, 95% CI 1.36–5.40, p = .005). Acceptable heterogeneity (I2 = 27%) was observed in the primary hernia subgroup, and high heterogeneity (I2 = 88%) was observed in the recurrent hernia subgroup (Fig. 3A). However, TEP repair group required less postoperative analgesia compared with the TAPP repair group after excluding the oldest publication from the analysis (Peto OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.36–0.89, p = .01) [3,4,5, 9]. In the recurrent hernia subgroup, no differences were observed between the two groups (Peto OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.34–2.03, p > .05; Fig. 3B). When the oldest research was excluded from the analysis, the degree of heterogeneity decreased from 88 to 0% among all the studies, including those involving recurrent hernia data. Sensitivity analysis also proved that the result was only influenced by the oldest RCT (Supplementary Material 4, S4.3).

Twelve RCTs reported surgery duration [4, 6,7,8, 10, 18, 20,21,22,23,24,25]. The meta-analysis of 1235 patients revealed no significant differences between TEP and TAPP repair (MD − 4.40, 95% CI − 18.31 to 9.50, p > .05; I2 = 99%). The result was also no significant in sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Material 4, S4.4). The evidence indicated no significant differences in surgery duration between the two repair groups in the primary hernia subgroup (MD − 7.10, 95% CI − 24.43 to − 10.22, p > .05). However, surgery duration was shorter in the TAPP repair group than in the TEP repair group after including recurrent hernia data (MD 3.35, 95% CI 0.16–6.54, p = .04). High heterogeneity (I2 = 99%) was observed in the primary hernia subgroup, and low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) was found in the recurrent hernia subgroup (Fig. 4A). Because funnel plot asymmetry cannot be tested for less than ten studies [26], surgery duration is the only outcome to reach statistical significance in this systematic review. Egger’s regression intercept (t value 1.226, p > .5) and Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation (τ − 0.090, p > .05) showed no publication bias. The fail–safe N value was 18, indicating that the p value may be influenced to exceed .05 when 18 additional “null” studies were included in meta-analysis. The funnel plot was shown in Supplementary Material 5.

Eight RCTs involving 778 patients showed no significant differences in hospital stay (hours) between the two laparoscopic approaches (MD − 0.82, 95% CI − 1.98 to 0.35, p > .05; I2 = 20%) [4, 6, 7, 10, 21,22,23, 25]. Sensitivity analysis showed that trend of the result was not influenced by any included RCT (Supplementary Material 4, S4.5). However, patients in the primary hernia subgroup who underwent TEP repair had shorter hospital stay than did those who underwent TAPP repair (MD − 0.87, 95% CI − 1.67 to − 0.07, p = .03). In the recurrent hernia subgroup, no differences were reported between the two patient groups (MD 6.68, 95% CI − 9.55 to 22.92, p > .05). Low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) was observed in the primary hernia subgroup, and high heterogeneity (I2 = 78%) was found in the recurrent hernia subgroup (Fig. 4B).

Further analysis of pain score

Eight RCTs reported pain scores after inguinal hernia repair [4, 7, 8, 10, 18, 20,21,22]. Seven of these studies calculated the pain score by using the visual analog scale [4, 8, 10, 18, 20,21,22]. However, one study used a 4-point scale and therefore was not included in the meta-analysis of pain scores [7]. The pooled data of 574 patients revealed no significant differences in pain scores at 1 h postoperatively between the TEP and TAPP repair groups (MD − 0.33, 95% CI − 0.88 to 0.23, p > .05; I2 = 94%; Fig. 5, 1.1.1). However, the evidence showed lower pain scores after TEP repair than after TAPP repair at 6 h (MD − 0.50, 95% CI − 0.77 to − 0.23, p = .0003; Fig. 5, 1.1.2), 1 day (MD − 0.52, 95% CI − 0.98 to − 0.06, p = .03; Fig. 5, 1.1.3), 1 week (MD − 0.60, 95% CI − 0.94 to − 0.26, p = .0005; Fig. 5, 1.1.4), and 1 month (MD − 0.25, 95% CI − 0.44 to − 0.06, p = .009; Fig. 5, 1.1.5) after hernia repair. There was a nonsignificant trend toward lower pain scores at 3 months in the TEP group compared to the TAPP group (MD − 0.20, 95% CI − 0.43 to 0.04, p = .10; Fig. 5, 1.1.6). At 6 months postoperatively, pain scores were not significantly different between the two groups. All meta-analysis results, except those obtained at 1 and 6 months postoperatively, showed moderate to high heterogeneity (I2 = 59–94%).

Discussion

Contribution of TEP and TAPP approaches to inguinal hernia

The present systematic review and meta-analysis including newer and more RCTs revealed the strengths of TEP and TAPP repair, despite previous meta-analyses reporting no significant differences between the clinical outcomes of these laparoscopic approaches for hernia repair. The present meta-analysis showed at least two advantages of TEP repair in primary cases, namely lower postoperative pain and shorter hospital stay, and also found an advantage of TAPP repair, namely shorter surgery duration.

With respect to post-operative pain in primary cases (Fig. 5), lower pain scores were recorded in the TEP group. The scores were significantly different in the short-term postoperative period, and the MD peak was obtained at 1 week postoperatively. With time and reduction in pain, the pain scores of the TEP and TAPP groups were comparable at 3 and 6 months, possibly because the extraperitoneal approach is associated with less peritoneal irritation. The innervation of T7–T12 and L1 spinal nerves, as well as the obturator nerve, revealed that the parietal peritoneum is sensitive to pain, temperature, touch, and pressure [27, 28]. TEP repair is performed between the parietal peritoneal and anterior abdominal wall. Unlike in TAPP repair, the peritoneum is not violated, possibly accounting for lower pain scores [4, 22]. Moreover, peritoneal irritation during laparoscopic hernia repair is mostly a self-limiting condition, thus justifying the differences in pain scores in the short-term post-operative period [18].

Analgesic consumption, a more objective and measurable factor for evaluating the severity of pain, is consistent with the pain score results. Among the primary cases, the TEP group had significantly less patients needing extra analgesic compared with the TAPP group. Among the recurrence cases, analgesic consumption was not different between the two groups, possibly because some terminal sensory branches were already damaged during the previous surgery. However, a study limitation is the lack of data on the type of surgical approach these patients underwent previously. The limitation might reasonably account for the high heterogeneity present in this subgroup. Contrastingly, the first RCT showed high disparity with other studies and had high heterogeneity in analgesic consumption. Because the first RCT of pooled studies was published only 3 years after the introduction of TAPP and TEP techniques, the proficiency level should be considered [21].

The significant difference in hospital stay favored TEP repair among the primary cases. High heterogeneity was present among the recurrence cases. Moreover, among the many factors that can affect hospital stay, postoperative pain may be a closely related factor [29].

Surgical duration was significantly shorter in the TAPP group of patients with recurrent hernia. It may be because sutures or scarring from previous repair complicates space creation and maintenance in TEP repair as the preperitoneum space is smaller and more difficult to dissect than the peritoneal cavity in the original anatomy [10, 30].

Comparison with previous research

This systematic review and meta-analysis has more advantages than do those published previously [11,12,13, 30, 31]. The strengths of the present study are the involvement of new RCTs, direct comparison, subgroup analysis, data verification, and modified statistical method. Moreover, three of five previous systematic reviews did not review RCTs [11, 12, 31]. Another review conducted indirect comparison, although it performed network meta-analysis [30]. The latest study conducted meta-analysis with RCTs and included 333 studies involving 10 RCTs that randomized 1047 patients into TEP and TAP repair groups [13]. That study reported similar effects of TAPP and TEP repair in inguinal hernia by generating forest plots of the hernia recurrence rate, pain scores, operation time, time to return to work, hospital stay, and complications without subgroup analysis of the hernia type.

The present systematic review and meta-analysis found 542 studies; among these, 16 RCTs were analyzed in all studies included in the previous systematic review. The 6 RCTs not included in the previous review consisted of 4 RCTs published in the recent 2 years [5, 10, 18, 21], and two published before 2015 [9, 20]. Therefore, the sample size in this systematic review and meta-analysis was larger than that in the previous study. When data-related problems were encountered in the data extraction phase, the investigators contacted the authors of the original RCTs and used correct data in their meta-analysis [22]. The previous meta-analysis recorded pain scores at 6 h post-operatively and favored TAPP repair. However, the result of the present analysis with corrected data favors TEP repair. Moreover, in this systematic review, subgroup analyses were conducted by hernia types according to available necessary data, which yielded important results in extra postoperative analgesia, surgery duration, and hospital stay. For dichotomous data showing a zero cell, this meta-analysis used Peto ORs rather than inverse RRs; therefore, the present findings may be more reliable.

Limitations and clues for future studies

Despite its strengths, the present meta-analysis has some limitations. These limitations may be reflected in the high heterogeneity observed with respect to pain scores and analgesic consumption (as discussed in previous sections), hospital stay for recurrent hernia, and surgery duration of primary hernia.

The pain score is a subjective parameter; the perception and expression of pain can be affected by many factors, including individual differences, personal experiences, and social implications. These factors may have complicated pain assessment and contributed to the high heterogeneity in this study [8]. Furthermore, a previous study reported that in patients older than 65 years, the presence of bilateral and indirect hernia is positively correlated with higher pain scores [22]. Future studies must determine how to objectively measure pos-toperative pain.

The patient condition and surgeon experience may influence surgery duration [13]. The hernia type and different technical difficulties in patients should be considered for determining their condition. However, in the present meta-analysis, subgroup analysis could not be performed because of incomplete records in pooled studies and the lack of an established system to assess difficulties encountered in hernia repair. With respect to surgeon experience, the surgery duration of inexperienced surgeons (< 20 repairs) may be almost twice that of experienced surgeons (30–100 repairs) [32]. Surgeon experience is an important factor that may affect surgery duration and recurrence rate, and it can result in a performance bias [33]. Therefore, further RCTs should be designed structurally for collecting the records of patient’s condition and surgeon’s experience in future.

Furthermore, the present systematic review cannot eliminate some methodological factors that may affect results. For instance, follow-up duration, a common factor, may influence the results, and it may cause detection biases. Typically, follow-up duration for hernia repair must be at least 5 years [34]. However, patients in five of the eight studies included in this systematic review were not followed for that duration. Considering these limitations, data on direct and indirect hernia were incomplete because these types of hernia can result in different technical difficulties in hernia repair. Future studies must provide suggestions for further analysis based on detailed records.

The data pooled from relevant RCTs revealed different effects of TEP and TAPP repair for inguinal hernia. Both approaches are advantageous. TEP reduces short-term postoperative pain more effectively than TAPP repair and is associated with shorter hospital stay of primary cases; TAPP repair has shorter surgery duration when recurrent hernia data were included. These findings emphasize shared decision-making regarding both approaches for laparoscopic hernia repair.

References

Schultz L, Graber J, Pietrafitta J, Hickok D (1990) Laser laparoscopic herniorraphy: a clinical trial preliminary results. J Laparoendosc Surg 1:41–45

Bittner R, Schwarz J (2012) Inguinal hernia repair: current surgical techniques. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 397:271–282

Pokorny H, Klingler A, Schmid T, Fortelny R, Hollinsky C, Kawji R, Steiner E, Pernthaler H, Függer R, Scheyer M (2008) Recurrence and complications after laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair: results of a prospective randomized multicenter trial. Hernia 12:385–389

Bansal VK, Misra MC, Babu D, Victor J, Kumar S, Sagar R, Rajeshwari S, Krishna A, Rewari V (2013) A prospective, randomized comparison of long-term outcomes: chronic groin pain and quality of life following totally extraperitoneal (TEP) and transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Surg Endosc 27:2373–2382

Ciftci F, Abdulrahman I, Ibrahimoglu F, Kilic G (2015) Early-stage quantitative analysis of the effect of laparoscopic versus conventional inguinal hernia repair on physical activity. Chirurgia 110:451–456

Dedemadi G, Sgourakis G, Karaliotas C, Christofides T, Kouraklis G, Karaliotas C (2006) Comparison of laparoscopic and open tension-free repair of recurrent inguinal hernias: a prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc 20:1099–1104

Gong K, Zhang N, Lu Y, Zhu B, Zhang Z, Du D, Zhao X, Jiang H (2011) Comparison of the open tension-free mesh-plug, transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP), and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 25:234–239

Hamza Y, Gabr E, Hammadi H, Khalil R (2010) Four-arm randomized trial comparing laparoscopic and open hernia repairs. Int J Surg 8:25–28

Mesci A, Korkmaz B, Dinckan A, Colak T, Balci N, Ogunc G (2012) Digital evaluation of the muscle functions of the lower extremities among inguinal hernia patients treated using three different surgical techniques: a prospective randomized study. Surg Today 42:157–163

Sharma D, Yadav K, Hazrah P, Borgharia S, Lal R, Thomas S (2015) Prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and laparoscopic totally extra peritoneal (TEP) approach for bilateral inguinal hernias. Int J Surg 22:110–117

McCormack K, Wake BL, Fraser C, Vale L, Perez J, Grant A (2005) Transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) versus totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review. Hernia 9:109–114

Wake BL, McCormack K, Fraser C, Vale L, Perez J, Grant AM (2005) Transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) vs totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online): CD004703

Wei FX, Zhang YC, Han W, Zhang YL, Shao Y, Ni R (2015) Transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) versus totally extraperitoneal (TEP) for laparoscopic hernia repair: a meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 25:375–383

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I (2005) Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 5:13

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327:557–560

Wolf FM (1986) Meta-analysis: quantitative methods for research synthesis. Sage, London

Bansal VK, Krishna A, Manek P, Kumar S, Prajapati O, Subramaniam R, Kumar A, Kumar A, Sagar R, Misra MC (2017) A prospective randomized comparison of testicular functions, sexual functions and quality of life following laparoscopic totally extra-peritoneal (TEP) and trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) inguinal hernia repairs. Surg Endosc 31:1478–1486

Butler RE, Burke R, Schneider JJ, Brar H, Lucha PA Jr (2007) The economic impact of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: results of a double-blinded, prospective, randomized trial. Surg Endosc 21:387–390

Gunal O, Ozer S, Gurleyik E, Bahcebasi T (2007) Does the approach to the groin make a difference in hernia repair? Hernia 11:429–434

Jeelani S, Ahmad MS, Dar HM, Abass MF, Mushtaq A, Ali U (2015) A comparative study of transabdominal preperitoneal verses totally extra-peritoneal mesh repair of inguinal hernia. Appl Med Res 1:57–61

Krishna A, Misra MC, Bansal VK, Kumar S, Rajeshwari S, Chhabra A (2012) Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) versus totally extraperitoneal (TEP) approach: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 26:639–649

Schrenk P, Woisetschlager R, Rieger R, Wayand W (1996) Prospective randomized trial comparing postoperative pain and return to physical activity after transabdominal preperitoneal, total preperitoneal or Shouldice technique for inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 83:1563–1566

Wang WJ, Chen JZ, Fang Q, Li JF, Jin PF, Li ZT (2013) Comparison of the effects of laparoscopic hernia repair and lichtenstein tension-free hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 23:301–305

Zhu Q, Mao Z, Yu B, Jin J, Zheng M, Li J (2009) Effects of persistent CO2 insufflation during different laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 19:611–614

Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, Carpenter J, Rucker G, Harbord RM, Schmid CH, Tetzlaff J, Deeks JJ, Peters J, Macaskill P, Schwarzer G, Duval S, Altman DG, Moher D, Higgins JP (2011) Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 343:d4002

Drake R, Vogl AW, Mitchell AW (2012) Gray’s basic anatomy E-book: with STUDENT CONSULT online access. Elsevier Health Sciences, New York

Snell RS (2011) Clinical anatomy by regions. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore

Mouton WG, Bessell JR, Otten KT, Maddern GJ (1999) Pain after laparoscopy. Surg Endosc 13:445–448

Bracale U, Melillo P, Pignata G, Salvo ED, Rovani M, Merola G, Pecchia L (2012) Which is the best laparoscopic approach for inguinal hernia repair: TEP or TAPP? A systematic review of the literature with a network meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 26:3355–3366

Dedemadi G, Kalaitzopoulos I, Loumpias C, Papapanagiotou A, Karaliotas C, Lyra S, Papatheodorou A, Sgourakis G (2014) Recurrent inguinal hernia repair: what is the evidence of case series? A meta-analysis and metaregression analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 24:306–317

Bittner R, Arregui ME, Bisgaard T, Dudai M, Ferzli GS, Fitzgibbons RJ, Fortelny RH, Klinge U, Kockerling F, Kuhry E, Kukleta J, Lomanto D, Misra MC, Montgomery A, Morales-Conde S, Reinpold W, Rosenberg J, Sauerland S, Schug-Pass C, Singh K, Timoney M, Weyhe D, Chowbey P (2011) Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia [International Endohernia Society (IEHS)]. Surg Endosc 25:2773–2843

Kukleta JF (2006) Causes of recurrence in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. J Minim Access Surg 2:187–191

Pikoulis E, Daskalakis P, Psallidas N, Karavokyros I, Stathoulopolos A, Godevenos D, Leppaniemi A, Tsatsoulis P (2005) Marlex mesh Prefix plug hernioplasty retrospective analysis of 865 operations. World J Surg 29:231–234

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L-SC identified evidence systematically, critically appraised the included articles, acquired the data, managed data, and drafted the first version of manuscript. W-CC identified evidence systematically, critically appraised the included articles, interpreted the result of analysis, and critically revised the manuscript. Y-NK designed the study, identified evidence systematically, critically appraised the included articles, analyzed the data, interpreted the result of analysis, critically revised the manuscript, and supervised research. C-CW identified evidence systematically, and critically reviewed the manuscript. L-WT proposed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript. M-ZL interpreted the result of analysis, interpreted the result of analysis, critically reviewed the manuscript, and supervised research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Li-Siou Chen, Wei-Chieh Chen, Yi-No Kang, Chien-Chih Wu, Long-Wen Tsai, and Min-Zhe Liu have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, LS., Chen, WC., Kang, YN. et al. Effects of transabdominal preperitoneal and totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: an update systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc 33, 418–428 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6314-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6314-x