Abstract

Dysphagia and its associated complications are expected to be relatively more frequent in stroke patients in Brazil than in similar patients treated in developed countries due to the suboptimal stroke care in many Brazilians medical services. However, there is no estimate of dysphagia and pneumonia incidence for the overall stroke population in Brazil. We conducted a systematic review of the recent literature to address this knowledge gap, first screening citations for relevance and then rating full articles of accepted citations. At both levels, judgements were made by two independent raters according to a priori criteria. Fourteen accepted articles underwent critical appraisal and data extraction. The frequency of dysphagia in stroke patients was high (59% to 76%). Few studies assessed pneumonia and only one study stratified patients by both dysphagia and pneumonia, with an increased Relative Risk for pneumonia in patients with stroke and dysphagia of 8.4 (95% CI 2.1, 34.4). Across all articles, we identified bias related to: heterogeneity in number and type of stroke; no rater blinding; and, assessments that were not reproducible, reliable or validated. Despite the high frequency of dysphagia and associated pneumonia in stroke patients in Brazil, the quality of the available literature is low and that there is little research focused on these epidemiologic data. Future rigorously designed studies are in dire need to accurately determine dysphagia incidence and its impact on stroke patients in Brazil. These data will be critical to properly allocate limited national resources that maximize the quality of stroke care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Brazil has a high incidence of stroke (137 per 100,000 inhabitants per year) [1] compared to stroke rates worldwide [2]. Stroke is one of the leading causes of death and disability in this country [3,4,5,6], yet there is little focus on the control of risk factors for stroke among the Brazilian population [4, 7, 8], and access to treatments such as cerebral reperfusion therapy is restricted to few hospitals [5, 9]. Furthermore, across Brazil, the general population has limited knowledge about stroke as an urgent medical emergency and few healthcare professionals have specialized training in stroke [4, 10]. All these factors contribute to delays in hospital admission and consequently to the high mortality and disability due to stroke throughout Brazil [5, 10, 11].

In an effort to promote better stroke recovery, Brazilian stroke guidelines [12] have been developed to align with those in North American [13, 14] and in the United Kingdom (UK) [15]. Like their worldwide counterparts, these guidelines recommend timely cerebral reperfusion therapy for eligible patients, dysphagia screening as soon as the patient is awake and alert, and care from a dedicated multi-disciplinary stroke team [13,14,15]. However, approximately only 1% of all patients with stroke admitted to a Brazilian public hospital receive reperfusion therapy and/or specialized care during their acute stay [6, 9, 16]. As a result, many stroke patients in Brazil continue to receive suboptimal stroke care and thus remain at high risk for post-stroke complications.

Dysphagia affects approximately half of the stroke patients [17,18,19] and contributes to pulmonary complications [17, 20,21,22]. The rate of pneumonia in stroke patients worldwide is around 14% [23], and of those stroke patients with dysphagia the risk for pneumonia is eight times greater [24]. Length of hospital stay in patients with stroke and dysphagia is up to 4 days longer than patients without dysphagia [25], and in-hospital mortality rate in dysphagic patients is around 11% to 16% [20, 26]. Due to the suboptimal stroke care in Brazil, it is expected that dysphagia and its associated pulmonary complications will be relatively greater than in similar patients treated in developed countries. However, to date, there is no estimate of dysphagia incidence for patients with stroke in Brazil [27]. This epidemiologic data point would be critical to allocate limited national resources that serve to maximize the quality of stroke care, and provide a benchmark for future research focused on interventions that reduce dysphagia and its negative impact on health. In a first effort to address this knowledge gap, our study conducted a systematic review of the literature on patients with stroke in Brazil with the aim to derive a country specific estimate of both dysphagia frequency and an associated risk for aspiration pneumonia.

Materials and Methods

Study Objectives

Our study was guided by the following objective: to identify the reported frequency of oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke patients across the recovery continuum in Brazil. We also aimed to identify the reported frequency of pneumonia in stroke patients with and without oropharyngeal dysphagia in Brazil.

Our secondary aims were to assess the frequency of dysphagia according to various characteristics of stroke (i.e., type), dysphagia assessment (i.e., clinical versus instrumental), and time of dysphagia assessment post-stroke.

Operational Definitions

The following operational definitions were used in the search and determined a priori: oropharyngeal dysphagia, defined as any physiological impairment affecting the oral, pharyngeal and/or upper esophageal phases of swallowing; pneumonia, defined as any infection in one or both of the lungs (if pneumonia was reported, the criteria by which it was defined had to be declared); and stroke, defined as any confirmed diagnosis by medical and/or imaging exams and treated in acute, rehabilitation, or chronic facilities (public and/or private) and regardless of stroke type or location.

Search Strategy

We performed an extensive electronic search to identify relevant articles from all languages published using the databases Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, IBECS, Lilacs, and the Scientific Electronic Library Online (Scielo) from their start date to August 14th, 2017. The following terms were included and combined in each database as appropriate: “deglutition, deglutition disorders, swallowing, swallowing disorders, oropharyngeal, dysphagia, stroke, cerebrovascular diseases, Brasil and Brazil” (see Appendix for full search strategies).

Study Selection

Two independent raters reviewed all citations according to an a priori exclusion criteria, which included: no abstract; tutorials, narrative reviews, or study protocol; > 10% of patients were < 18 years; > 10% of patients had a diagnosis other than stroke; oropharyngeal dysphagia or aspiration were not reported outcomes; < 10 patients with stroke occurring in Brazil; and, conference proceedings. All selected abstracts went forward to full article review by the two independent raters where these and additional exclusion criteria were applied: not consecutive enrolment; no data to label presence/absence of dysphagia using a gold standard test (i.e., clinical assessment by SLP, videofluoroscopy (VFS) and/or Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES); > 10% of patients with a diagnosis other than stroke; unclear raw data; and same data as an included study. Disagreements in abstract and full article ratings were resolved by consensus with a third rater.

Data Extraction

Only full articles that did not meet the exclusion criteria outlined above underwent data extraction. One rater extracted the data from each article and summarized the relevant data descriptively in tabular form. A second rater checked the accuracy of data extraction for each article. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Analysis of Risk of Bias

Each included article was assessed for Risk of bias according to Cochrane reviews methodology [28]. This included five main categories: Selection Bias, Performance Bias, Detection Bias, Attrition Bias, and Reporting Bias. One rater assessed all articles and a second rater checked the accuracy of risk data for each article. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data Analysis

The frequency of dysphagia between the studies was derived according to characteristics of stroke, methods of assessment, and time of assessment post-stroke event using proportions. For studies that included pneumonia rates for those with/without dysphagia, we derived Relative Risks (RR) along with their 95% CI for the risk of developing pneumonia associated with dysphagia.

Results

Literature Retrieval

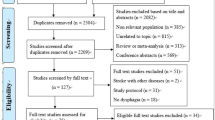

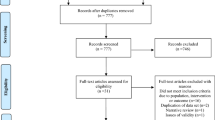

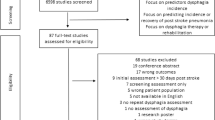

We identified 643 citations across all data sources. Duplicates were removed, the remaining 426 abstracts were screened, of which 79 were accepted for full article review. Of these articles, 65 did not meet our inclusion criteria and the remaining fourteen were included in our study (Fig. 1).

Study Characteristics

The study characteristics for all included articles are summarized in Table 1. The timing of dysphagia assessment post-stroke event varied across studies, with studies including patient within 48 h [29, 30] to more than 6 months after stroke [38].

Across all studies, the number of patients sampled per study ranged from 26 [32, 35, 37] to 212 patients [40]. Age of stroke patients ranged from 20 [33] to 94 years [30], with thirteen studies [27, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, 39,40,41] reporting mean ages in the sixth decade.

The stroke characteristics varied across all studies. Namely, seven studies [27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 35, 40] included patients with both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, another four studies [31, 34, 37, 41] included only ischemic stroke and the remaining three studies [36, 38, 39] did not report the type of stroke.

Across all studies that utilized clinical assessment of dysphagia, all but one included bedside assessment by an SLP, utilizing a variety of food stimuli and scoring protocols (Table 1). The one exception [38] judged dysphagia presence according to a level of functional diet with a standardized tool, the Functional Oral Intake Scale - FOIS [42]. In additional to a clinical assessment, four studies [29, 31, 38, 39] used FEES to assess dysphagia, with three of them [29, 31, 39] using the Penetration-Aspiration Scale (score ≥ 6) and one study [38] using Macedo Filho Scale [43] to define the presence of aspiration (Table 1). Two other studies [27, 36] also administered videofluoroscopy, but it was done with dysphagic patients only, therefore, their data were not included.

Across all studies, the food consistencies used to assess the swallow varied, with most: studies [27, 30, 33, 34, 36, 38, 40, 41] utilizing solid, paste, and liquid. In addition to consistency, the volume per mouthful used in the assessments ranged from 3 mL [27, 30, 33, 40, 41] to 50 mL [30, 33]. Four other studies also included free or unrestricted volumes [29, 31, 40, 41].

Dysphagia presence was scored as clinical signs of risk for aspiration in three studies [31, 34, 35] and in five studies [27, 30, 33, 37, 40] they scored dysphagia as impairments in both oral and pharyngeal phase.

The co-occurrence of dysphagia and pneumonia was assessed in only four studies [31, 35, 37, 40]. One study [31] assessed pneumonia after 3 months of stroke and another study [35] in the first week of stroke. Two studies [37, 40] did not detail the time of pneumonia assessment. One study [35] assessed pneumonia with chest x-ray, another study [37] from patient report, and the two other studies [31, 40] did not report how they assessed pneumonia. No study declared an operational definition for pneumonia.

Critical Appraisal

Our critical appraisal of the accepted articles is summarized in Table 2. Of all 14 articles, four studies [33,34,35, 37] clearly included a homogenous sample of patients with either first time stroke and four studies [31, 34, 37, 41] included only ischemic stroke; the remaining studies introduced a risk for selection bias by including a mixed study population. Specifically, either selecting patients with mixed stroke events [30, 38,39,40] or not specifying number of strokes [27, 29, 31, 32, 36, 41]; or including both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes [27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 35, 40]; or failing to report on type of stroke [36, 38, 39]. Only two studies [33, 35] reported on stroke severity.

Eleven of the fourteen studies [27, 29,30,31,32,33, 35,36,37, 39, 41] included patients with varying age. One study [38] introduced a risk for selection bias with only elderly patients (61–90 years), and the two other studies did not report age range [34, 40].

Two studies [34, 41] introduced a risk for detection bias because the clinicians who rated for presence of dysphagia were not blinded to stroke details, and the remaining studies were unclear about rater blinding. Eight studies [29,30,31, 33, 37,38,39,40] provided enough details regarding the dysphagia assessment method to ensure reproducibility. However, two of these studies [37, 40] did not use a previously validated method to score dysphagia.

Frequency of Dysphagia Identified from Clinical Assessment

The reported frequency of overall dysphagia identified by clinical assessment ranged from 32 [41] to 80% [40]. In studies that assessed patients within 72 h, the frequency of dysphagia ranged from 42 [31] to 52% [30] and between studies that assessed within 10 days post-stroke this frequency ranged from 48 [34] to 76% [27, 35]. The frequency was higher in studies that assessed also patients with more than 10 days post-stroke, which ranged from 76 [36] to 80% [40] (Fig. 2).

In studies that included only patients with ischemic stroke, the frequency of overall dysphagia was lower than in studies that also included also hemorrhagic stroke, ranging between 32 [41] and 48% [34] versus 52% [30] to 80% [40], respectively (Fig. 3). In studies that included patients with only first stroke, the reported frequency of dysphagia was also lower than in studies that included patients with mixed stroke events, ranging between 48% [34] and 76% [33] versus 52% [30] to 80% [40], respectively (Fig. 4). Finally, in studies that scored dysphagia broadly capturing both oral and pharyngeal phase impairments, the frequency of overall dysphagia was higher than in studies that scored dysphagia based on pharyngeal phase only, ranging between 52 [30] to 80% [40] versus 42% [31] to 48% [34], respectively.

Across studies with similar design and patient inclusion [27, 33, 40], such as those with acute patients with mixed stroke types and assessing dysphagia broadly using paste, liquid, and solid food consistencies, the frequency of dysphagia on clinical assessment ranged from 59 [40] to 76% [27, 33].

Frequency of Dysphagia Identified from Instrumental Assessment

Across the studies that utilized instrumental assessment for dysphagia, reported frequencies varied by operational definition for dysphagia and the food consistency. A broad definition of dysphagia in one study [39] reported a frequency of 58% in acute patients and of 62% in chronic patients. A narrow definition of dysphagia that is referring only to aspiration was utilized in two studies, which then reported a dysphagia frequency between 35 [31] to 40% [39].

Frequency of Pneumonia

The frequency of pneumonia ranged between none [35] to 15% [40]. In the study that assessed pneumonia within the first week of stroke [35] no patient presented with pneumonia. The three other studies [31, 37, 40] reported a frequency of pneumonia at 5.7%, 3.6%, and 15%, respectively. Of these, only one study [40] stratified patients by both dysphagia and pneumonia and reported that 22% of patients with stroke and dysphagia presented pneumonia and only 2% of patients with stroke and no dysphagia had pneumonia. Using these data, we derived an increased Relative Risk for pneumonia in patients with stroke and dysphagia of 8.4 (95% CI 2.1, 34.4) versus the same patients with stroke and no dysphagia.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review about dysphagia and associated pneumonia in stroke patients specific to Brazil. Our findings identified few studies that met our inclusion criteria, but within these studies identified dysphagia was reportedly a common consequence in patients with stroke in Brazil. These data highlight the importance of implementing strategies to manage dysphagia in this population to avoid complications. Unfortunately, the methodological quality of the available literature is fraught with potential risks for bias across several categories; thereby, limiting both the internal and external validity of these frequency estimates.

Across the included studies, reported frequencies varied by select study characteristics, namely: time of assessment post-stroke, stroke type, number of stroke events, and operational definition for dysphagia. Dysphagia frequency was lower in studies evaluating patients early post-stroke [29,30,31,32] compared to studies evaluating dysphagia 72 h or later post-stroke [27, 33,34,35], likely because the studies that assessed swallowing early did not include patients with more severe stroke. Unfortunately, these studies did not report the severity of stroke at the time of swallowing evaluation, which precludes objective assessment of frequency by stroke severity and tie of assessment. Likewise, we identified differences in reported frequency of dysphagia by stroke type, in that those with ischemic stroke [31, 34, 37, 41], lower rates than studies with mixed stroke types [27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 35, 40]. These findings align with others that have shown higher dysphagia rates with hemorrhagic stroke [18, 44]. Our findings also identified lower dysphagia frequency in studies with first stroke [31, 34] when compared to studies with mixed stroke [30, 40] and are supported by other studies that have shown higher dysphagia rates with mixed stroke events [45, 46].

Our results showed that the reported frequency of overall dysphagia varied by how dysphagia was assessed. Specifically, dysphagia rates were lower in studies that utilized only clinical signs of aspiration [31, 34]. Likewise, assessments that did not capture the entire oropharyngeal swallow physiology were also lower and likely underestimated dysphagia frequency [17]. The clinical swallow assessment alone will likely underestimate dysphagia presence as it may miss silent aspiration events [47, 48]. Yet, only few of our included studies used instrumental exams to assess the frequency of dysphagia [29, 31, 38, 39]. This is likely a reflection of the current limitation in most Brazilian medical services for the assessment of dysphagia [40]. However, interestingly of the few studies we identified that utilized instrumental exams, our findings showed a higher rate for overall dysphagia of any type (58% to 62%) compared to the rate for dysphagia restricted to be defined as aspiration alone (35% to 40%), a contrast that aligns with findings from other studies outside of Brazil [17].

The estimate of dysphagia in patients with stroke identified in the Brazilian studies (between 59 and 76%) is higher than the estimate reported in studies from developed countries included in the systematic review from Martino et al. [17], 51-55%, and than the frequency of dysphagia identified in studies of cohorts from developed countries such as Spain [26], Canada [20], and Italy [18], 47%, 45%, and 50%, respectively. The estimate identified in this systematic review is also higher than some studies in emerging countries such as South Africa (53%) [49] and India (42%) [50].

The rate of pneumonia reported in a Brazilian cohort study was 15% [40], which is like the rate of pneumonia worldwide, and is interestingly lower than the rate of other emerging countries such as Chile (23%) [51] and India (32%) [50]. Although the presence of pneumonia is a known complication in stroke patients with dysphagia [17], only one [40] of our included studies assessed this association. Their findings showed that the risk for pneumonia in stroke patients with dysphagic was 8.4 (95% CI 2.1, 34.4) times higher than in similar patients without dysphagia. This estimated risk is higher than that for stroke patients in studies from developed countries reported in the systematic review from Martino et al. [17], which have a risk 3.2 (95% CI 2.1, 4.9); but it is similar to estimated risk of pneumonia reported in a recent systematic review from Eltringham et al. [24], which found a risk 8.5 (95% CI 5.6, 13). Unfortunately, this increased pneumonia risk related to the Brazilian literature could only be derived from this one study as the other studies with pneumonia data [31, 35, 37] did not report its presence according to dysphagia. Furthermore, pneumonia was not operationally defined any of these four studies, limiting the validity of the findings.

As with all systematic reviews, our study findings are limited by the quality of the original studies. Specifically, these studies did not provide details that are known to impact dysphagia presence, such as: stroke type [36, 38, 39]; first time or mixed stroke (multiple stroke events) [27, 29, 31, 32, 36, 41]; sites involved [27, 31, 36, 37, 39]; stroke severity [27, 29,30,31,32, 34, 36,37,38,39,40,41] and time of assessment [41]; food consistency and volume used [32]; and how dysphagia [32, 36, 41] or pneumonia [31, 35, 37, 40] were defined. Furthermore, these studies presented with a potential risk for detection bias because: dysphagia was rated subjectively and without tools with adequate psychometric validation [27, 32, 34,35,36,37, 40, 41]; and there was no blinding of dysphagia raters to stroke details [34, 41]. These methodological flaws can contribute to errors that overestimate or underestimate dysphagia and associated pneumonia frequencies due to rater subjectivity or missed events [49].

Despite the low number of Brazilian studies that met the selection criteria for this systematic review, it is important to highlight that there is a great interest in research on stroke and dysphagia in Brazil, considering the high number of conference proceedings and tutorials/narratives identified.

In conclusion, and despite methodological weaknesses in the literature, this systematic review highlights the high incidence of dysphagia and associated pneumonia in stroke patients in Brazil. These data are important for health service managers who promote strategies for early detection and adequate dysphagia care. Our study further shows that the quality of the available literature is low and that there is little research focused on stroke patients in Brazil and the rates of dysphagia and associated pneumonia. Future properly designed studies focused on stroke, dysphagia, and their concomitant risk for aspiration pneumonia will be critical to accurately inform future up-dates of Brazilian stroke guidelines and ultimately optimize dysphagia care in patients with stroke.

References

Minelli C, Fen LF, Minelli DPC. Stroke Incidence, Prognosis, 30-Day, and 1-Year Case Fatality Rates in Matão, Brazil A Population-Based Prospective Study. Stroke. 2007;38:2906–11.

Thrift AG, Thayabaranathan T, Howard G, et al. Global stroke statistics. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(1):13–32.

Lotufo PA. Stroke is still a neglected disease in Brazil. Sao Paulo Med J. 2015;133(6):457–9.

Pontes-Neto OM. Stroke awareness in Brazil: what information about stroke is essential? Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72(12):909–10.

de Carvalho JJ, Alves MB, Viana GA, et al. Stroke epidemiology, patterns of management, and outcomes in Fortaleza, Brazil: a hospital-based multicenter prospective study. Stroke. 2011;42(12):3341–6.

Pontes-Neto OM, Cougo-Pinto PT, Martins SC, et al. A new era of endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke: what are the implications for stroke care in Brazil? Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2016;74(1):85–6.

Lotufo PA. Stroke in Brazil: a neglected disease. Sao Paulo Med J. 2005;123(1):3–4.

Copstein L, Fernandes JG, Bastos GA. Prevalence and risk factors for stroke in a population of Southern Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2013;71(5):294–300.

Martins SC, Pontes-Neto OM, Alves CV, et al. Past, present, and future of stroke in middle-income countries: the Brazilian experience. Int J Stroke. 2013;8(A100):106–11.

Pontes-Neto OM, Silva GS, Feitosa MR, et al. Stroke awareness in Brazil: alarming results in a community-based study. Stroke. 2008;39(2):292–6.

Leopoldino JF, Fukujima MM, Silva GS, et al. Time of presentation of stroke patients in São Paulo hospital. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003;61(2A):186–7.

Martins SC, et al. Manual de rotinas para atenção ao AVC. Brasília: Editora do Ministério da Saúde; 2013.

Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870–947.

Hebert D, Lindsay MP, McIntyre A, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: stroke rehabilitation practice guidelines, update 2015. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(4):459–84.

Rudd AG, Bowen A, Young G, et al. National clinical guideline for stroke. 5th ed. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2016.

Pontes-Neto OM, Cougo P, Martins SC, et al. Brazilian guidelines for endovascular treatment of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017;75(1):50–6.

Martino R, Foley NC, Bhogal SK, et al. Dysphagia after stroke: incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2756–63.

Paciaroni M, Mazzotta G, Corea F, et al. Dysphagia following Stroke. Eur Neurol. 2004;51(3):162–7.

Smithard DG, O’Neill PA, Parks C, et al. Complications and outcome after acute stroke. Does dysphagia matter? Stroke. 1996;27(7):1200–4.

Joundi RA, Martino R, Saposnik G, et al. Predictors and outcomes of dysphagia screening after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2017;48(4):900–6.

Arnold M, Liesirov K, Broeg-Morvay A, et al. Dysphagia in acute stroke: incidence, burden and impact on clinical outcome. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0148424.

Al-Khaled M, Matthis C, Binder A, et al. Dysphagia in patients with acute ischemic stroke: early dysphagia screening may reduce stroke-related pneumonia and improve stroke outcomes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;42:81–9.

Kishore AK, Vail A, Chamorro A, et al. How is pneumonia diagnosed in clinical stroke research? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2015;46(5):1202–9.

Eltringham SA, Kilner K, Gee M, et al. Impact of dysphagia assessment and management on risk of stroke-associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;46:97–105.

Attrill S, White S, Murray J, et al. Impact of oropharyngeal dysphagia on healthcare cost and length of stay in hospital: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:594.

Rofes L, Muriana D, Palomeras E, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and complications of oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke patients: a cohort study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;23:e13338.

Schelp AO, Cola PC, Gatto AR, et al. Incidence of oropharyngeal dysphagia associated with stroke in a regional hospital in São Paulo State - Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62(2B):503–6.

Higgins JP, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley; 2008. p. 187–241.

Nunes MC, Jurkiewicz AL, Santos RS, et al. Correlation between brain injury and dysphagia in adult patients with stroke. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;16(3):313–21.

Mourão AM, Almeida EO, Lemos SM, et al. Evolution of swallowing in post-acute stroke: a descriptive study. Rev CEFAC. 2016;18(2):417–25.

Pinto G, Zétola V, Lange M, et al. Program to diagnose probability of aspiration pneumonia in patients with ischemic stroke. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;18(3):244–8.

Jacques A, Cardoso MC. Stroke followed by speech and language sequels: Hospital Procedures. Rev Neurocienc. 2011;19(2):229–36.

Otto DM, Ribeiro MC, Barea LM, et al. Association between neurological injury and the severity of oropharyngeal dysphagia after stroke. Codas. 2016;28(6):724–9.

Barros AF, Fábio SR, Furkim AM. Relation between clinical evaluation of deglutition and the computed tomography in acute ischemic stroke patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64(4):1009–14.

Marques CH, Rosso AL, André C. Bedside assessment of swallowing in stroke: water tests are not enough. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2008;15(4):378–83.

Xerez DR, Carvalho YS, Costa MM. Clinical and videofluoroscopic study of dysphagia in patients with cerebrovascular accident in subacute phase. Radiol Bras. 2004;37(1):9–14.

Silva AC, Dantas RO, Fabio SR. Clinical and scintigraphic swallowing evaluation of post-stroke patients. Pro Fono. 2010;22(3):317–24.

Mituuti CT, Bianco VC, Bentim CG, et al. Influence of oral health condition on swallowing and oral intake level for patients affected by chronic stroke. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:29–35.

Diniz PB, Vanin G, Xavier R, et al. Reduced incidence of aspiration with spoon-thick consistency in stroke patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2009;24(3):414–8.

Baroni AF, Fábio SR, Dantas RO. Risk factors for swallowing dysfunction in stroke patients. Arq Gastroenterol. 2012;49(2):118–24.

Okubo PC, Fábio SR, Domenis DR, et al. Using the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale to predict dysphagia in acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;33(6):501–7.

Crary MA, Mann GD, Groher ME. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(8):1516–20.

Macedo Filho ED. Avaliação Videoendoscópica da Deglutição (VED) na abordagem da disfagia orofaríngea. In: Jacobi JS, Levy DS, Silva LMC, editors. Disfagia Avaliação e Tratamento. Rio de Janeiro: Revinter; 2003. p. 332–42.

Smithard DG, Smeeton NC, Wolfe CD. Long-term outcome after stroke: does dysphagia matter? Age Ageing. 2007;36(1):90–4.

Mourão AM, Lemos SM, Almeida EO, et al. Frequency and factors associated with dysphagia in stroke. Codas. 2016;28(1):66–70.

McCullough GH, Rosenbek JC, Wertz RT, et al. Utility of clinical swallowing examination measures for detecting aspiration post-stroke. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005;48(6):1280–93.

McCullough GH, Wertz RT, Rosenbek JC. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical/bedside examination signs for detecting aspiration in adults subsequent to stroke. J Commun Disord. 2001;34(1–2):55–72.

Donovan NJ, Daniels SK, Edmiaston J, et al. Dysphagia screening: state of the art: invitational conference proceeding from the State-of-the-Art Nursing Symposium, International Stroke Conference 2012. Stroke. 2013;44(4):e24–31.

Ostrofsky C, Seedat J. The South African dysphagia screening tool (SADS): a screening tool for a developing context. S Afr J Commun Disord. 2016;63(1):117.

Sundar U, Pahuja V, Dwivedi N, et al. Dysphagia in acute stroke: correlation with stroke subtype, vascular territory and in-hospital respiratory morbidity and mortality. Neurol India. 2008;56(4):463–70.

Hoffmeister L, Lavados PM, Comas M, et al. Performance measures for in-hospital care of acute ischemic stroke in public hospitals in Chile. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:23.

Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, et al. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11(2):93–8.

Trapl M, Enderle P, Nowotny M, et al. Dysphagia bedside screening for acute-stroke patients: the gugging swallowing screen. Stroke. 2007;38(11):2948–52.

Ellul J, Barer D, Fall S. Improving detection and management of swallowing problems in acute stroke: a multi-centre study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1997;7:18.

Silva RG. Disfagia neurogênica em adultos pós-acidente vascular encefálico: identificação e classificação. Dissertation. São Paulo: Universidade Federal de São Paulo; 1997.

O’Neil-Pirozzi TM, Lisiecki DJ, Jack Momose K, et al. Simultaneous modified barium swallow and blue dye tests: a determination of the accuracy of blue dye test aspiration findings. Dysphagia. 2003;18(1):32–8.

Silva RG, Gatto AR, Cola PC. Disfagia orofaríngea neurogênica em adultos - avaliação fonoaudiológica em leito hospitalar. In: Jacobi JS, Levy DS, Silva LMC, editors. Disfagia avaliação e tratamento. Rio de Janeiro: Revinter; 2003. p. 181–93.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank National Council of Scientific and Technological Development of Brazil (CNPq) and Coordination of Improvement of Higher Level Personnel (CAPES). Support from National Council of Scientific and Technological Development of Brazil (CNPq – 482721/2013-8 and 402388/2013-5) and Coordination of Improvement of Higher Level Personnel (CAPES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect of the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Research Ethics Committee and Informed Consent

All studies included in this systematic review involving human subjects declared that they were performed after approval by the appropriate Research Ethics Committee and that the written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pacheco-Castilho, A.C., Vanin, G.M., Dantas, R.O. et al. Dysphagia and Associated Pneumonia in Stroke Patients from Brazil: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia 34, 499–520 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-019-10021-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-019-10021-0