Abstract

Swallowing problems are reported to be a common finding in patients who receive palliative care. In existing literature, the incidence of swallowing problems is mostly described in small numbers of patients at the start of the palliative phase. As we hypothesized that the incidence of dysphagia might increase as the palliative phase progresses, this study describes the incidence of swallowing problems and related problems in 164 unsedated patients at the end of the palliative phase, defined by the last 72 h before their death. To determine the incidence of swallowing problems and related problems, questionnaires were completed bereaved by relatives and nursing staff. Our data shows that in the palliative phase the incidence of swallowing problems can be as high as 79 %. A significant correlation was found between swallowing problems and reduced psycho-social quality of life as assessed by nursing staff (ρ = −.284). Overall the nursing staff rated the incidence and severity of swallowing problems (and related problems like frequent coughing, loss of appetite, and problems with oral secretions) lower than the relatives. This study suggests that incidence of swallowing problems at the end of the palliative phase is high and that these difficulties may not only result in discomfort for patients, but also can raise concern for caregivers. More information and education on management of swallowing problems in palliative settings might be needed for both relatives and nursing staff. However, the data also suggest that any intervention should be proportional to the level of distress caused by the intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The western population is aging [15]. Life expectancy is increasing, to which the medical capability to prolong life, and the decrease in the frequency of unexpected and sudden death contributes substantially. As a result, chronic diseases, such as cancer, cerebrovascular disease, and dementia are becoming more common. Growing numbers of people will die from chronic diseases, demanding care for specific symptoms in the dying phase [15, 16].

Literature on the prevalence and management of swallowing problems in patients in the palliative care settings is scarce. Pollens [7] stated in a review that swallowing difficulties may result in discomfort for patients and concern from caregivers. In this review of literature, possible roles of the speech-language pathologist in hospice are described. One of these roles is “to provide consultation to patients, families, and members of the hospice team in the areas of communication, cognition, and swallowing function” [7].

Stringer [11] and Ripamonti et al. [9] described in their articles that swallowing problems are common in palliative care. They also suggested that swallowing problems are a predictive factor concerning quality of life in palliative care patients [9, 11]. A recent study by Raijmakers et al. [8] described that 23 bereaved relatives noted significant changes in patients’ oral intake at the end of life [8]. Although these studies make strong recommendations for caregivers, they do not quantify the magnitude of swallowing problems in palliative care. Langmore et al. described in 2009 in detail the management of swallowing problems in patients who receive palliative care Langmore et al. [6], but authors did not quantify these problems.

Other studies aimed at identifying and quantifying quality of life in the palliative care setting which tends to include a small number of patients only. Roe et al. [10] described that seven out of eleven patients with non-head and neck cancers receiving specialist palliative care had swallowing problems [10]. Tada et al. [12] described quality of life in 24 patients in a hospice setting using the EORTC-QLQ-C30 [12], while Gourdji et al. [4] interviewed ten patients receiving palliative care Gourdji et al. [4].

Studies that include larger number of patients only tend to describe patients at the start of the palliative phase Jocham et al. [2, 5]. The period in which palliative care is provided to a patient however can last from a few months up to as much as 2 years Voogt et al. [14]. Therefore, questions arise about the applicability of studies that only measured symptoms or quality of life at the start of palliative care, as one might hypothesize that the incidence of certain symptoms might increase as the palliative phase progresses and death becomes inevitable.

In this study, focus is on the incidence of swallowing problems and related problems in the final phase of palliative care (i.e., the dying phase), defined as the last 72 h before death [13], as this might better reflect the magnitude of these problems. By proxy assessment, we attempted to establish the incidence of swallowing problems and related problems in patients in this phase, in order to explore further directions for the possible role of speech-language pathologists in the management of dysphagia in palliative settings.

Methods

General Methods and Questionnaire Items

This study is based on data which were collected for a general study on the quality of care in the dying phase in the hospital, nursing home, and home care setting [13]. The effects of introducing the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient (LCP) on the content of care and the quality of life of the dying patient were determined in this study. For each deceased patient, a nurse and a bereaved relative were asked to fill in a questionnaire (i.e., proxy assessment).

In this current study, the four items regarding swallowing problems and (psycho-social and physical) well-being were selected from the original data pool. Selected data were used to determine the incidence of swallowing problems in unsedated patients in the dying phase and the influence on quality of life. The questions regarding possible swallowing problems and related problems are presented in Table 1. For determining the well-being of the patient, both the relatives and the nursing staff were asked to rate the psycho-social function and physical well-being on a scale, rating from 1 (lowest possible) to 10 (highest possible).

Data Collection

General information about the patient, such as age and diagnosis, was obtained from the medical and nursing records.

Patients and Respondents

Patients from different types of healthcare settings were included. All settings were located in the southwest of The Netherlands. For each deceased patient, one questionnaire was sent to the patient’s relative. Participating relatives gave written informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the relevant local Dutch Medical Ethics Committees.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All patient data from the LCP-study [13] were initially included in this study. Included were data only of patients those who were in the dying phase (i.e., within 72 h of dying) and were not sedated. Excluded were data of patient of which not both the relatives and nursing staff had returned the questionnaires.

Statistical Analysis and Considerations

For statistical analysis, IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used. To determine possible differences between responses provided by relatives and nursing staff, a Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test was used. The correlations between each of the items of the questionnaire were calculated using a Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient (ρ). A correlation of 0.30 or less is considered to represent a weak correlation, between 0.30 and 0.70 to represent a substantial correlation and a coefficient of 0.70 and above represents a strong correlation [1].

To determine the incidence of symptoms, the outcome of the questionnaire was dichotomized; when the answer ‘not at all’ was given, it was interpreted as an absence of the symptom. All other answers were interpreted as a presence of this symptom. Additional analyses were performed to determine possible differences in incidence of the four symptoms in patients with a malignancy and in patients with a non-malignant disease. A Mann–Whitney test was used to explore possible differences in incidence between groups. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine differences in rating of quality of life between groups. All statistical tests were two-tailed and were evaluated with a 5 % level of significance with the power set at 0.80.

Results

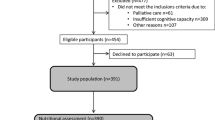

The data of 489 patients collected in the study by Veerbeek [13] were initially used. For each deceased patient, one questionnaire was sent to the patient’s relative. The response rate was 59.7 % (n = 292) for the relatives and 96.5 % (n = 472) for the nursing staff. After exclusion of patients for whom only one of the two respondent groups (relatives, nursing staff) had returned the questionnaire (n = 198), sedated and unconscious patients (n = 34), the data of 164 patients were included in the study.

The mean age of patients was 76.5 years (range 19.0–100.3). Thirty-four percent of the patients were male (n = 55). The largest proportion of all patients (53 %, n = 87) were living in a nursing home at the time when the dying phase set in. Fifty patients were admitted in a hospital (30.5 %) and 27 patients were living at home and receiving homecare (16.5 %). The largest group of responding relatives (46 %, n = 75) consisted of either the patient’s son or daughter. Thirty-four percent of all responding relatives (n = 56) were partners/spouses and 32 of all respondents (20 %) had another relationship to the patient, such as a cousin or close friend. In one case, a patient’s parent filled out the questionnaire. Ninety-seven patients (60.2 %) had a malignancy and 64 patients had a non-malignant disease (39.8 %). Three patients had an unclear diagnosis. The characteristics of included patients are presented in Table 2.

Swallowing problems, frequent coughing, loss of appetite, and problems with oral secretions were all frequent findings in patients in the dying phase. In 78.7 % of all patients, the respondents reported that their relative suffered from swallowing problems in the last 72 h before death. In 53 cases (37.6 %), they reported that these problems were severe. Nursing staff reported a 65.8 % incidence of swallowing problems in the same patient group. Overall the nursing staff rated the incidence and severity of swallowing problems lower than the relatives (Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test; p < .0001).

Both relatives and nursing staff reported a higher incidence of swallowing problems in non-malignancy patients (81.5 and 79.5 %) compared to patients with malignancies (76.5 and 58.1 %; p = .039 and p = .030 resp.). For the other symptoms, there were no differences found between patients with/without malignancies.

Comparing responses provided by relatives and nursing staff, differences in rating of incidence and severity were found for the items ‘frequent coughing’, ‘loss of appetite,’ and ‘problems with oral secretions’ (p = .012, p = .001 and p = .002 resp.). For the items ‘frequent coughing’ and ‘loss of appetite,’ the median severity grading by nursing staff was significantly lower compared to the relatives’ grading. The outcomes of the questionnaires are represented in Table 3.

Relatives reported different incidences of swallowing problems, coughing, and loss of appetite differently across settings (home care setting, nursing home, general hospital, and university hospital, Friedman test, p < .0001). No differences in problems with oral secretions were reported across the different locations (p = .365). According to relatives, the incidences of swallowing problems in a home care setting were 75.0 %, in nursing homes 81.4 %, in general hospitals 84.6 %, and 64.3 % in university hospitals. Nursing staff reports included no differences in the incidence of swallowing problems across the different locations (p = .819), but they did report differently for the other symptoms (p < .0001).

For three symptoms (swallowing problems, frequent coughing, and problems with oral secretions), a significant correlation was found between the grading given by relatives and nursing staff. For coughing and problems with oral secretions, this correlation was substantial (ρ = .313 and ρ = .326 resp.), for swallowing problems the found correlation was weak (ρ = .289), and no correlation was found for loss of appetite (p = .123) (Table 4).

Correlations between the four symptoms observed by relatives and nursing staff are presented in Table 5. A significant correlation was found between almost all symptoms for the relatives, except for ‘loss of appetite’ and ‘frequent coughing’ (p = .414), and for ‘loss of appetite’ and ‘problems with oral secretions’ (p = .163). The strongest correlation was found between ‘swallowing problems’ and ‘problems with oral secretions’ (r = .470; p < .0001). For the nursing staff, a significant correlation was found for ‘loss of appetite’ and ‘swallowing problems’ (r = .411; p < .0001) and between ‘problems with oral secretions’ and ‘swallowing problems,’ ‘frequent coughing,’ ‘loss of appetite’ (ρ = .219; p = .017, ρ = .415; p < .0001 and ρ = .203; p = .011 resp.).

Patients’ well-being in the dying phase was rated by the relatives at 4.9 (SD ± 3.3; range 1–10) for psycho-social functioning and at 2.5 (SD ± 2.5; range 1–10) for physical well-being. The nursing staff rated psycho-social functioning at 4.5 (SD ± 2.7; range 1–10) and physical well-being at 2.7 (SD ± 2.1; range 1–10). No statistical differences were found between the rating by relatives and nursing staff regarding the patients’ psycho-social functioning and physical well-being (Wilcoxon; p = .783 and p = .230 resp.).

No significant correlation between any of the four symptoms and the patient’s psycho-social well-being was found for the relatives’ assessments. A significant correlation was found for the nursing staff’s assessments of swallowing problems and their patients’ rating of psycho-social well-being (ρ = −.2584; p = .002). A significant, but weak, correlation was found between the relatives’ assessment of physical well-being and swallowing problems (ρ = −.261; p = .002). For the nursing staff’s assessment, this correlation was also found to be significant, but more substantial (ρ = −.358; p < .0001). Also a weak, but significant, correlation was found between the patients’ physical well-being and the nursing staff’s assessment of loss of appetite (ρ = −.282; p < .0001) (Table 6).

Discussion

This study is the first in quantifying the incidence of swallowing problems in the final stage of palliative care. One of the limitations of this study is the use of proxy assessment, which might introduce different types of bias (like recall bias and observer bias) into this study. However, one might suggest that this type of assessment is the only acceptable method of collecting data in these patients. Other assessment methods might raise ethical issues in this specific phase, where both patients and relatives are extreme vulnerable. And although this type of assessment might have its limitations, the reliability of proxy assessment for various aspects of end-of-life care and quality of life, however, is well described by Veerbeek [13].

Our study identifies not only a high incidence, but also a difference in perception of these problems.

In our population, 76 % of all patients had swallowing symptoms as reported by relatives; nursing staff reported swallowing problems in 66 % of all patients. The incidence of swallowing problems in patients with non-malignancies is reported to be higher than in patients with malignancies. This was to be expected as the incidence of swallowing problems in diseases like stroke, motor neuron diseases, and dementia which are known to be high. However, our data shows that in palliative settings, the incidence of swallowing problems in patients with non-malignant diseases might be as high as 60 %, which might lead to considerable emotional burden for not only the patient, but also for the relatives as in a large study. Yamagashi et al. [17] concluded that 70 % of family members were very distressed when faced with a situation when a terminal relative was unable to eat or drink. These findings underline the importance of adequate management of swallowing problems in the palliative setting.

In our study, the assessment of severity of swallowing problems by relatives differs from the assessment by nursing staff. Relatives’ responses suggest that they might relate swallowing problems in the dying phase to all other symptoms, whereas nursing staff responses suggest that they only correlate loss of appetite with swallowing problems. Although none of the found coefficients indicates a strong correlation, the fact that relatives seem to correlate all symptoms with one another, might suggest that relatives might have difficulty in differentiating these symptoms. In our study, relatives rate the severity of swallowing problems higher than nursing staff. An explanation for this phenomenon might be that nursing staff provide care for many patients; they might use these experiences as a reference. Also, one could suggest that the emotional attachment of the relatives could be a confounding factor in the subjective rating of severity of swallowing problems in a period where relatives most likely are to have a higher emotional load. The discrepancy in the rating of severity of swallowing does suggest, however, a need for a better communication between relatives and nursing staff. Raijmakers et al. [8] studied the relatives’ perspective of the patient’s oral intake toward the end of life in 23 patients and found that relatives recalled limited communication with health care professionals concerning oral intake at the end of life. The results of our study seem to support the findings by Raijmakers et al. [8] and underline the need for providing adequate information on swallowing problems to the relatives when a patient receives palliative care. Our data suggest however that this information should not be limited to swallowing problems only, but also focus on the links between these problems and other clinical symptoms, like loss of appetite. In 2010, Yamagishi et al. proposed a four-domain care strategy for family members of a terminally ill cancer patient who becomes unable to take nourishment orally: (1) relieving the family members’ sense of helplessness and guilt, (2) providing up-to-date information about hydration and nutrition at the end of life, (3) understanding family members’ concerns and providing emotional support, and (4) relieving the patient’s symptoms. These recommendations are in line with our findings in this study.

Literature suggests that swallowing problems can lead to a decrease of well-being and social functioning, even in a fragile patient group in a palliative setting [6, 7]. Based on the reported high incidence in our population, there is undoubtedly a need for the management of swallowing problems in the palliative phase. Palliative care in some cases may extend over a longer period (up to several years) [14], whereas our study focuses on the last phase, when the incidence of problems is hypothesized to be maximal. Health care professionals should be thoroughly aware that in this study we found that swallowing problems did not correlate with the patient’s psycho-social well-being according to relatives and only correlate weakly with physical function according to nursing staff. This would suggest that the impact of any swallowing intervention on the patients’ well-being would diminish as the patient gets closer to the dying phase. Based on our data, it might be suggested that swallowing interventions in the last phase of palliative care should be more directed toward providing information to the patient, their relatives, and nursing staff then toward interventions like exercises. Our data support the findings of Pollens [7] that swallowing difficulties may result in discomfort for patients and concern from caregivers, however our data also suggest that at the end of the palliative phase, the possible impact of any intervention could be minimal. Some literature suggests that signals of hunger and thirst are naturally reduced in the dying phase and are reported to have an analgesic-like effect (Ferris [3]). Yamagishi et al. [17] describe that in other qualitative studies, family members said that, before being informed by health care providers, they were not aware that decreased oral intake is normal for terminally ill patients and that it caused minimal discomfort. This would strongly suggest that any intervention should be proportional to the level of distress caused by the intervention.

Conclusion

Swallowing problems are reported to be a common finding in patients who receive palliative care. Our study is the first attempt to quantify these problems in the end stage of palliative care. The incidence of swallowing problems in the last 72 h is 79 % in 164 unsedated patients. Relatives and nursing staff assess the severity of symptoms differently, suggesting that more information by speech pathologists on care and management of swallowing problems in these settings is needed. Differences were also found between patients’ locations during the dying phase.

Our findings quantify and support previous findings on the incidence of swallowing problems in a palliative care setting, but also suggest that specifically at the end of the palliative phase, the impact of any interventions for these problems on quality of life are minimal, suggesting that any proposed intervention should be proportional to the level of distress caused by the intervention. Future research should be aimed at providing a framework in which patients (and relatives) in a palliative care setting would be provided with adequate information on swallowing problems and the links between these problems and other clinical symptoms. Any other intervention should be proportional to the level of distress caused by the intervention.

References

Aday LA. Designing and conducting health surveys. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1996.

Chui YY, Kuan HY, Fu IC, Liu RK, Sham MK, Lau KS. Factors associated with lower quality of life among patients receiving palliative care. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(9):1860–71.

Ferris FD. Last hours of living. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20(4):641–67.

Gourdji I, McVey L, Purden M. A quality end of life from a palliative care patient’s perspective. J Palliat Care. 2009;25(1):40–50.

Jocham HR, Dassen T, Widdershoven G, Halfens RJ. Quality-of-life assessment in a palliative care setting in Germany: an outcome evaluation. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2009;15(7):338–45.

Langmore SE, Grillone G, Elackattu A, Walsh M. Disorders of swallowing: palliative care. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009;42(1):87–105.

Pollens R. Role of the speech-language pathologist in palliative hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(5):694–702.

Raijmakers NJ, Clark JB, van Zuylen L, Allan SG, van der Heide A. Bereaved relatives’ perspectives of the patient’s oral intake towards the end of life: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2013;27(7):665–72.

Ripamonti CI, Farina G, Garassino MC. Predictive models in palliative care. Cancer. 2009;115(13 Suppl):3128–34.

Roe JW, Leslie P, Drinnan MJ. Oropharyngeal dysphagia: the experience of patients with non-head and neck cancers receiving specialist palliative care. Palliat Med. 2007;21:567–74.

Stringer S. Managing dysphagia in palliative care. Prof Nurse. 1999;14(7):489–92.

Tada T, Hashimoto F, Matsushita Y, Terashima Y, Tanioka T, Nagamine I, et al. Investigation of QOL of hospice patients by using EORTC-QLQ-C30 questionnaire. J Med Investig. 2004;51(1–2):125–31.

Veerbeek L (2008) Care and quality of life in the dying phase. The contribution of the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient. Thesis. Rotterdam: Erasmus University/University Medical Center Rotterdam.

Voogt E, van Leeuwen AF, Visser AP, van der Heide A, van der Maas PJ. Information needs of patients with incurable cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(11):943–8.

WHO. Palliative care: the solid facts. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2004.

WHO. Better palliative care for older people. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2004.

Yamagishi A, Morita T, Miyashita M, Sato K, Tsuneto S, Shima Y. The care strategy for families of terminally ill cancer patients who become unable to take nourishment orally: recommendations from a nationwide survey of bereaved family members’ experiences. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;40(5):671–83.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bogaardt, H., Veerbeek, L., Kelly, K. et al. Swallowing Problems at the End of the Palliative Phase: Incidence and Severity in 164 Unsedated Patients. Dysphagia 30, 145–151 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9590-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9590-1