Abstract

The costs of reproduction are important in shaping individual life histories, and hence population dynamics, but the mechanistic pathways of such costs are often unknown. Female reindeer have evolved antlers possibly due to interference competition on winter-feeding grounds. Here, we investigate if variation in antler size explains part of the cost of reproduction in late winter mass of female reindeer. We captured 440 individual Svalbard reindeer a total of 1426 times over 16 years and measured antler size and body mass in late winter, while presence of a ‘calf-at-heel’ was observed in summer. We found that reproductive females grew smaller antlers and weighed 4.3 kg less than non-reproductive females. Path analyses revealed that 14% of this cost of reproduction in body mass was caused by the reduced antler size. Our study is therefore consistent with the hypothesis that antlers in female Rangifer have evolved due to interference competition and provides evidence for antler growth as a cost of reproduction in females. Antler growth was constrained more by life history events than by variation in the environment, which contrasts markedly with studies on male antlers and horns, and hence increases our understanding of constraints on ornamentation and life history trade-offs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Horns and antlers of ungulates are among the most extravagant ornamentations seen in nature, and their large variation in form, size and function has intrigued natural historians for centuries (Gould 1992). Today, the evolution of horns and antlers in male ungulates is attributed to sexual selection (Bro-Jørgensen 2007; Clutton-Brock 1982; Geist 1966). In polygynous species, male reproductive success is limited by access to mates (Clutton-Brock et al. 1988). Antlers are honest signals of body size, and potentially fighting ability, and are decisive for the outcome of male–male combats determining dominance rank and access to mates (Bro-Jørgensen 2007; Clutton-Brock et al. 1980, 1982). As expected for an honest signal of competitive ability, the production of antlers is costly and may account for as much as 1/3 of summer energy intake (Moen et al. 1999). In contrast to males, female reproductive success is limited by the energy available to allocate to offspring. The absence of female mate contests and high cost of growing antlers may be the main reason why female cervids, typically, are antlerless. The presence of antlers in female reindeer and caribou (Rangifer tarandus ssp.) stands out as an intriguing exception, and the function and consequences of antlers for female life history remain poorly documented.

Arguably, reindeer are the most social cervid species inhabiting harsh alpine and arctic environments. During winter, they dig craters to access forage under the snow, a process which is energetically costly and increasingly so with more snow (Fancy and White 1985). Access to craters, therefore, may often lead to interference competition (Espmark 1964). While adult males cast antlers shortly after the autumn rut, females retain them throughout winter. Further, population-level studies have found a higher proportion of antlered females in areas with deep snow in winter (Schaefer and Mahoney 2001). Several mechanisms have been suggested to explain the fitness benefits of horns in female ruminants (Packer 1983; Roberts 1996; Stankowich and Caro 2009), but the function of antlers in female reindeer is currently understood in terms of interference competition (Espmark 1964).

Antler growth in Rangifer females starts after calving in June and continues throughout the summer and autumn. This coincides with the period of lactation and peak energy allocation in offspring (Espmark 1971). The amount of energy allocated to horn and antler growth depends on the quality and quantity of plant biomass (Festa-Bianchet et al. 2004; Mysterud et al. 2005; Smith 1998; Thalmann et al. 2015) and population density (Prichard et al. 1999; Schmidt et al. 2001; Vanpé et al. 2007) during the antler development period. Presumably, the additional cost associated with the production of antlers during lactation is compensated by the benefit of antlers during winter improving relative fitness. However, to date no study has followed individual female reindeer over multiple years to investigate the constraints and energy allocation trade-off associated with antler production and the consequences for body mass and reproductive success in the next breeding event. This is the aim of the current study.

We use a unique longitudinal data set of 440 female Svalbard reindeer (Rangifer tarandus platyrhynchus) repeatedly captured between 2002 and 2017. Plant biomass measured in early August, shortly before senescence, varied twofold between years as a function of July temperature (van der Wal and Stien 2014). During the last two decades, there has been significant warming in both summer and winter (Albon et al. 2017) and the study population size has nearly doubled (Lee et al. 2015). In winter, food is often restricted to small patches on wind-blown ridges where reindeer aggregates, especially when deep snow or rain on snow (ROS), which can lead to the formation of ice-encrusted pastures, limits access elsewhere (Hansen et al. 2010). Consequently, our study provides a unique opportunity to explore, first, the limiting factors on antler growth, and, second, the impact of female antlers on fitness traits, under rapidly changing environmental conditions.

We predict that, (P1a), antler size is resource limited and positively affected by warm summers with higher plant biomass (van der Wal and Stien 2014), (P1b), early plant phenology in spring (due to longer plant growth season), and (P1c), low population size (decreased intraspecific competition for resources). We expect a trade-off in energy allocation between antler growth and provisioning for a calf, both energy-draining processes occurring in summer. Thus, we predict that (P2) provisioning for a calf in summer reduces contemporary antler growth. Previously, we have documented that rearing a calf has a negative effect on body mass lasting until the end of the next winter (Albon et al. 2017). Because small antlers are expected to inhibit the competitive abilities on the winter-feeding grounds, we predict (P3) that some of the cost of reproduction in late winter body mass is caused by reduced antler growth.

Materials and methods

Study area and the reindeer population

The study was conducted in Nordenskiöld Land, Spitsbergen, Svalbard. The study area (77°50′N-78°20′N, 15°00′E-17°30′E) of about 150 km2 includes the three interconnected valleys, Reindalen, Semmeldalen and Colesdalen, with adjoining side valleys (Fig. S1). At this high latitude, there is 4 months of midnight sun and 4 months of polar night. The mean air temperature (1981–2010) for the warmest (July) and for the coldest month (February) was 5.8 °C and − 13 °C, respectively (Nordli et al. 2014). Snow covers the area from October/November until mid-June, but varies considerably between years. The vegetation is classified as middle Arctic tundra zone (Elvebakk 2005). The valley floors are mainly vegetated by acidic mires bryophytes, graminoids and herbs (Elvebakk 2005). Ridge habitats, often wind blown and exposed in winters, and snow free early in spring, are dominated by the dwarf shrubs Dryas octopetala and Salix polaris (van der Wal and Stien 2014).

The population of Svalbard reindeer in our study area has varied from 750 to around 1750, with an increasing trend between 1994 and 2014 (estimate only of females and calves; Lee et al. 2015). In summer, the reindeer forage on widely dispersed and easily accessible graminoids and herbs on lower ground, while in winter they concentrate on wind-blown ridges, depending on snow and ice conditions. Like in many other Rangifer populations, restricted food patches and cratering behaviour create an opportunity for interference competition over forage (Schaefer and Mahoney 2001), although Svalbard reindeer are less gregarious than other subspecies of Rangifer. The mean late winter body mass of adult females varies between years from ca 40 to 57 kg (Albon et al. 2017) depending on ROS and autumn temperature. Antler mass ranges from about 120 g for a pair with three tines per beam to 350 g for a set with six tines, a difference of about 200–250 g (Brage B, Hansen unpublished results). The annual antler cycle depends on sex, age and fertility status (Bergerud 1976; Espmark 1971). Unlike prime-aged males, which clean their antlers in August, and cast them shortly after the rut, females possess their antlers through the winter and, if pregnant, cast the antlers a week or two after giving birth. Non-pregnant females usually cast their antlers a few weeks earlier (Espmark 1971; Weladji et al. 2005). Antler growth starts immediately after the old ones are cast, and in females the velvet is cleaned after the rutting season in October and early November (length of rutting season is not well known; Skogland 1989). A highly synchronized calving season takes place during c. 10 days in early June (Tyler 1987). Svalbard reindeer is the only large herbivore in the archipelago, and predation by polar bears (Ursus maritimus) is a very rare cause of mortality (Derocher et al. 2000).

Reindeer data

The Svalbard reindeer population in the study area has been monitored by capture–mark–recapture since 1994 (Albon et al. 2017) and measurements of antlers have been collected since 2002. During the study period, female adults, yearlings and calves of both sexes were captured in February (2007–2011 only) and/or late winter (late March–April all years) using two snowmobiles and a handheld net (see Omsjø et al. 2009 for detailed description of the methodology). A total of 1426 captures of 440 different adult females (of known age and antler status) were made between 2002 and 2017, with a median of 79 per year; range 59–122. All individuals included in this study were of known age, because they were either captured as calves (at 10–11 months of age; 91.3%), as yearlings (22–23 months of age; 5%), or aged after death (3.7%) based on counts of cementum annuli (Reimers and Nordby 1968). Most individuals were only captured once per year (April), but a subset of 164 adult females were captured both in February and April the same year (mean interval = 57 days; range 49–71) between 2007 and 2011. In cases where the antlers were measured more than once per winter, the first measurement was used (antlers do not grow from February to April). At first capture, individuals were fitted with numbered plastic collars and ear tags. Captured individuals were restrained manually and weighed to the closest 0.5 kg. The number of tines on each antler beam was recorded, and from 2014, the length of antlers was recorded with a soft tape measure following the outer curve of the main antler beam. The practical field definition of an antler tine was that it needs to be long and pointed enough to be able to hold a thin camera strap.

Of the 431 individuals captured twice or more, 52 individuals were observed without antlers on at least one occasion. Of these, 42 (9.7% of all individuals) had antlers in other years, while only 10 individuals (2.3%) were always observed antlerless as adults (median number of captures of antlerless females = 4.5; range 2–12). This suggests that being antlerless one or a few years is rather common, and only a small subset of females is permanently antlerless. Antler size of zero was therefore included in the analysis and treated as part of a continuum of allocation in antlers.

Observations of calf status took place in July and August each year during a census of the study area, registering whether marked females had a ‘calf-at-heel’, or not. The animals were not captured at this time and summer body mass was unknown. Not all marked individuals were observed in consecutive summer and winter and, therefore, there is only partial overlap between individuals captured in winter and seen the following summer.

Environmental data

Meteorological data were collected at Svalbard airport (78°25′N, 15°46′E, 28 m altitude) approximately 20–40 km north of the study area and were available from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute (www.eklima.no; Fig. S1). ROS was calculated as the amount of precipitation that fell when mean daily temperature was above 1 °C between November 1 and April 30 (Stien et al. 2012). ROS events occurring in the winter immediately prior to the birth of an individual (ROS in utero) were used to test for a cohort effect on adult antler growth (Douhard et al. 2016). The enhanced vegetation index (EVI) was used as a proxy for plant phenology in spring (Tveraa et al. 2013; Veiberg et al. 2017), while mean July temperature was used as a proxy for peak annual plant biomass (van der Wal and Stien 2014), which together with estimates of annual population size (Albon et al. 2017) was used to test for resource limitation in antler growth.

Matching the reindeer and environmental data in time

The antlers produced in the summer of calendar year t0 were measured in the subsequent winter in calendar year t1. When testing for effects of resource limitation, we therefore use environmental variables (including population size) measured in year t0 (prediction P1) as predictors of antler sizes measured in year t1. Similarly, the effects of calf production in year t0 (cost of reproduction) on antler sizes are modelled with respect to antler sizes measured in year t1 (P2). When investigating the direct and indirect (through antlers) cost of reproduction on subsequent winter body masses, the model included calf status in year t0, antler size measured in year t1 and April body mass measured in year t1 (P3; Fig. 1).

A conceptual figure showing how the term cost of reproduction (abbreviated C.O.R in the figure) is used in our study. The effects of giving birth and provisioning for a calf causes reduced contemporary antler growth, termed cost of reproduction in antler growth. Giving birth to a calf also causes a cost of reproduction in the next winter body mass. This effect can be direct (termed direct cost of reproduction in body mass) or operate through reduced antler size (termed indirect cost of reproduction in body mass)

Statistical analyses

We document the overall age-related development in number of antler tines in Svalbard reindeer females from age 0 (calves of 10 months) and onwards (Fig. 2). However, since 2 years is the youngest age of first reproduction in female Svalbard reindeer, calves and yearlings are not included in subsequent analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.3.1 (R Core Team 2016).

We first investigated if the number of tines was an adequate proxy for antler size, as found in other cervids (Clutton-Brock et al. 1982, page 159: r = 0.62; Mysterud et al. 2005: r = 0.57). We fitted a generalized additive model (GAM) using the mgcv package in R (Wood 2006) to assess a potential non-linear relationship between length and number of tines. In adult females (≥ 2 years of age), the number of antler tines correlated with antler length (r = 0.54, p < 0.001) in the subset of data where both measures were recorded (n = 355). The close to linear relationship (Fig. 3) suggests that the number of tines is a suitable proxy for antler size, and the number of tines is used because it was recorded over a longer time period (16 years versus 4 years). We used the average number of antler tines of the left and right beam (average = 3.5, sd = 1.8, range = 0–9) and this measure is henceforth referred to as antler size. Neither antler length nor the number of antler tines are perfect metrics of energy allocation to antlers, and also they describe two partly different antler dimensions (which could explain the relatively low correlation). Measuring antler volume, which would have been the best metric, was not feasible during our handling of live, captured reindeer.

Relationship between antler length (in centimetre) and number of antler tines per antler beam in female Svalbard reindeer. The unbroken lines represent the predicted relationship from a GAM model and dashed lines represent 95% CI. The average number of tines per beam in female reindeer was 3.2 and the average length of the antlers was 33 cm

Factors affecting antler size

Variation in annual antler size of individuals was analysed with linear mixed models using the functions “lmer” with a Gaussian error structure and the identity link function (Bates et al. 2015). Residual plots suggested that linear models with a Gaussian error structure fitted the data better than log-linear Poisson regression models. Metatarsus length (hind leg length) was included as fixed effect and not subjected to model simplification to account for static allometry between antler size and skeletal size. Statistical significance of all other model parameters was assessed using likelihood ratio tests (LRT) with cutoff value p = 0.05 (Pinheiro and Bates 2000). Preliminary analyses using age classes resulted in more parsimonious models than using a full factorial age factor (AIC 1475 vs. 1485). The most complex model included the following candidate reindeer variables as fixed effects: leg length (measured in mm), age category (2–3, 4–6, 7–13 years old; grouped according to previous life history work in Douhard et al. 2016), ‘calf-at-heel’ in August (yes or no). The following environmental variables were also included as fixed effects: ROS in utero (high or low, with a cutoff at 15 mm in line with Stien et al. 2012), plant phenology (EVI), population size (only available up to 2015; Lee et al. 2015) and mean July temperature. Also, we included July temperature residuals: the residuals from a regression between mean July temperature and population size. This measure is an index of per capita forage availability. Finally, we selected a random effect structure, where a model with individual ID as random effect was selected over a model with both year and ID and a model without any random effect (LRT p < 0.001). All continuous predictor variables were standardized at mean 0 and variance 1 to facilitate model convergence and direct comparison of effect sizes.

Cost of reproduction on next winters’ body mass

To estimate the average cost of reproduction on body mass at the end of the next winter, we fitted a linear mixed model with body mass in April in year t1 as response variable, presence of a ‘calf-at-heel’ (coded as 0 = no or 1 = yes) in August year t0 and age as the only fixed effects. Year and individual were fitted as crossed random intercepts; year to account for unexplained annual variation and individual to account for individual heterogeneity (assuming a normal distribution of individual ‘quality’). After this initial step, we proceeded by separating the direct and indirect (through antler size) cost of reproduction using a path analysis. The starting point of our path model is presence of a ‘calf-at-heel’ in August year t0 and the end point body mass in April in year t1 (ca 8 months later). A total of n = 580 had observed calf status year t and April mass in year t1, a prerequisite for being included in the analyses. We defined the following paths:

-

1.

Antler sizet1 as a function of ‘calf-at-heel’t0.

-

2.

April masst1 as a function of ‘calf-at-heel’t0 (direct cost of reproduction).

-

3.

April masst1 as a function of antler sizet1 (indirect cost of reproduction).

-

4.

‘Calf-at-heel’t as a function of body size (adult leg length).

-

5.

Antler sizet1 as a function of body size.

-

6.

April masst1 as a function of body size.

To test the fit of the model, we used the direct separation approach (“D-sep”, Shipley 2016), which provides a flexible way to test the implied conditional independences of the path model while accounting for the hierarchical nature of the data. We begin by testing the null probability (P) associated with all k mutually independent claims of independence that must be true for the structure of the hypothesized path model to be correct using linear mixed models. We then used these k probabilities obtained to calculate Fisher’s C statistic [− 2 Σ ln(P)]. Fisher’s C statistic follows a Chi-square distribution with 2 k degrees of freedom. A D-separation test with a p value ≤ 0.05 indicates that the proposed correlation structure of the model differs from that observed in the data, and the path model is therefore rejected. Path models were tested using the piecewise SEM package (Lefcheck 2016). Age was included as a covariate as a full factorial variable as this was more parsimonious than using age classes in the body mass sub-models (AIC = 1163.5 vs. 1164.2). Both year and ID were fitted as random effects in all regressions. The complete path model cannot be rejected given that all endogenous variables are conditionally dependent. Therefore, we tested the sub-model excluding the indirect cost of reproduction (path 3 above). We report the unstandardized path coefficients and associated p values for the paths in the supplementary material (Table S1 and S2). We multiplied the coefficients composing each path to obtain the direct and indirect cost of reproduction on body mass (Shipley 2016). The proportion of the cost due to indirect effect can then be obtained by dividing this cost by the sum of direct and indirect effects.

The motivation for two modelling choices needs further reasoning. First, we did not extend the path analyses to ‘calf-at-heel’t1 mainly because of reduced sample size (inclusion only of individuals observed in two consecutive summers and captured in the intervening winter; reducing sample size by 43%). However, when extending the path analyses to ‘calf-at-heel’t1 for this subset of individual-years (n = 328) the indirect antler effect remained significant (p < 0.001), explaining 12% of the variation in the probability to have a calf-at-heel. This is expected because body mass explains 92% of variation in the probability to have a calf-at-heel (Veiberg et al. 2017). The combination of severe sample size reduction and the known, strong relationship between body mass and reproduction were our reasons for keeping late winter body mass as the end point in the path analyses. Second, we included individual as a random intercept to account for potential confounding effect of individual heterogeneity. Still, as an additional test, we added late winter body mass t0 to the path analyses as a variable that could affect both antler growtht0 and body mass t1. However, on reducing sample size (n = 315), the indirect antler effect remained statistically significant (p < 0.001), explaining 9.6% of the variation in late winter body mass. To avoid sample size reduction, coefficients for models including body mass t0 are only provided as supplementary material (Table S3–S4).

Effect of antler size on winter mass loss

The effect of antler size on mass loss from February to April was investigated for the subset of individuals captured twice per winter. Mass loss per month ((February mass − April mass)/observation interval in days) × 30 days was used as the response variable in a linear mixed model. February mass and antler size (number of tines) were candidate fixed effects and year and ID random effects. The statistical significance of antler size on mass loss was evaluated using an LRT as described above.

Results

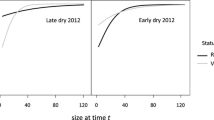

Contrary to prediction P1, antler size was not affected by any of the proxies for forage abundance and level of competition in summer (EVI, July temperatures, population size and July temperature residuals; all LRT: p ≥ 0.20; Table S5). Only age and calf status explained a significant amount of variation in antler size of adult females (Table 1; Fig. 4a). Antlers reached full size from age 4 and showed signs of senescence beyond age 13 (Fig. 2). Females rearing a calf grew about one tine less per antler beam than females without a calf (Table 1; Fig. 4a), supporting our prediction of a cost of reproduction in antler growth (P2). No second-order interactions were statistically significant (All LRT: p ≥ 0.33; Table S5). Although there was detectable annual variation in antler size (LRT: p < 0.001), the effect of year was no longer included in the best model when controlling for calf status. This is in line with the strong negative population-level correlation between the annual mean antler size and proportion of females with a ‘calf-at-heel’ (r = − 0.69; p = 0.003, Fig. 4b).

a Relationship between the average number of anter tines, age and calf status in female Svalbard reindeer. Points represent the observed mean values for the different combinations of age class and calf status (open circle: no calf; filled circle with calf) and error bars are 95% confidence limits. Lines represent predicted mean values from the additive model for the effect of age class and calf status that best explain variation in number of antler tines. b Relationship between the annual mean number of antler tines and proportion of females with a calf-at-heel in the previous summer, for all marked females 2 years and older. The estimates of mean number of antler tines are corrected for annual variation in age composition and repeated observations of individuals, but uncorrected estimates are very similar (r = 0.96) and show essentially the same pattern

Females with a ‘calf-at-heel’ in August year t0 were on average 4.3 kg (SE = 0.31) lighter than non-reproducing individuals at the end of next winter (April in year t1; ca 8 months later). The path analyses confirmed both a direct negative (− 3.8 kg) and an indirect negative (− 0.6 kg) effect of reproductive success on late winter body mass (Fig. 5), with the indirect antler effect accounting for 14% of the total cost of reproduction on body mass (supporting P3; Fig. 5). Path models excluding the indirect antler effect on body mass were rejected (p < 0.001). The strength of the indirect antler effect was not affected by age (neither the effect of calving on antler size nor the effect of antler size on body mass changed with age class; LRT: p = 0.358 and p = 0.090, respectively).

Graphical representation of the path model. Effect of reproductive success (Calf) on next winter body mass (Mass) is mediated through a direct effect and an indirect effect of antler size (Antler). Static allometry is accounted for by linking skeletal size (leg length) to antler size and body mass. Also, size is allowed to influence probability of calving. The values on the arrows are the standardized path coefficient with SE in brackets and are effectively correlation coefficients. The width of the arrow is proportional to the strength of the effect. Black paths (red in online version) indicate negative correlations and grey paths (green in online version) indicate positive correlations. Unbroken lines are statistically significant, while dotted lines represent non-significant correlations. The direct cost of reproduction is the calf-to-mass path coefficient (− 0.61). The indirect cost of reproduction is the product of the path coefficients for calf-to-antler (− 0.55) and antler-to-mass (0.18), which is − 0.10. The indirect effect accounts for 14% of the total effect (− 0.10/(− 0.61 + (− 0.10)) × 100)

Contrary to expectation, antler size did not affect mass loss between February and April for the much smaller subset of individuals weighed twice per winter (LRT: p = 0.11), but large antlers tended to reduce mass loss. Winter mass loss was on average 6 kg per month for a female weighing 60 kg in February (95% CI [5.4–6.6]; Table S6). Mean mass loss was reduced by 0.10 kg (95% CI = [− 0.02 to 0.23]) per month for each extra tine. This implies for example a 0.8 kg difference (over the 4 winter months from December to March before we capture them) between an individual with a four-tine antler (the 75% quantile) and one with two tines (the 25% quantile), which is comparable to the result from the path analysis.

Discussion

Our study of the role of antlers in female reindeer, the only cervid where females routinely grow antlers, provides the first quantitative evidence that a cost of reproduction on antler growth has carryover effects on late winter body mass. The negative effect of small antlers on late winter mass lends support to the long-held view that antlers in female Rangifer have evolved due to interference competition (see Espmark 1971). Antler size was constrained more by life history events (raising a calf reduced antler size), than annual variation in the environment, which is in marked contrast to studies on male antlers (Mysterud et al. 2005) and horns (Douhard et al. 2017; Festa-Bianchet et al. 2004).

Cost of reproduction in mass is partly caused by reduced antler growth

About 14% of the cost of reproduction on late winter body mass was likely to be the result of lactating females growing smaller antlers. This provides rare evidence for a cost of reproduction in mass operating partly through a secondary trait. The rationale behind this argument is, first, that due to a trade-off in energy allocation (Hamel and Côté 2009), females produce smaller antlers in summers, when they suckle a calf. Such reduced allocation in horns and antlers has previously been found in lactating bovids (mountain goats Oreamnos americanus; Côté et al. 1998) as well as in reindeer (Prichard et al. 1999). Second, small antlers potentially constrain competitive abilities on the winter-feeding grounds, resulting in lower body mass at the end of the next winter. Third, lower body mass is associated with reduced performance at the next breeding event (Albon et al. 2017; Veiberg et al. 2017), suggesting that stunted antlers not only have cost for late winter mass but also for the next breeding event. Other studies have reported on a simple direct cost of reproduction in body mass (Festa-Bianchet et al. 1998), and the majority of the cost of reproduction in mass (the remaining 86%) was attributed to such a direct effect also in our study.

Female antler size not linked to environmental variation

Theory predicts that because sexually selected traits are honest signals of condition and male quality, they are sensitive to environmental conditions (Andersson 1994). Consistent with this theory, the size of antlers in cervids (Mysterud et al. 2005; Schmidt et al. 2001), including female reindeer (Thomas and Barry 2005) and horns in male bovids (Festa-Bianchet et al. 2004) varies as a function of climate and population density, and tend to do so more than the body mass. In contrast, we found no link between antler size and environmental conditions in female reindeer. This is particularly surprising since both plant biomass (van der Wal and Stien 2014) and population size have varied twofold during the study (Lee et al. 2015) and affected summer body mass gain (Albon et al. 2017). Although the effect of increasing density and plant biomass to some extent may cancel each other in the long term (i.e. increased carrying capacity), there are considerable annual fluctuations in both variables.

Female antlers are much smaller than male antlers and they carry them through the energy-limited winter season. Carrying large antlers through snowy winters with high locomotion cost may clearly act as a selective force against substantially larger antlers. Also, the primary role of female antlers may be in intersexual competition with males that are antlerless in winter (Holand et al. 2004), suggesting that presence/absence of antlers is more important than absolute size. Nevertheless, the positive effect of antler size on late winter mass makes it surprising that females do not grow even larger antlers in summers when resources are plentiful and competition low.

The function of female weaponry

Our study provides the first evidence that some of the cost of reproduction in an ungulate species is due to reduced antler growth. Our results support the hypothesis that interference competition is the selective force for evolution of antlers in female Rangifer. This highlights not only that the function of antlers in male and female cervids differs, but also that they respond differently to environmental variability. A phylogenetic analysis of weaponry in female bovids found that the presence of horns was associated with large body size and open habitat (Stankowich and Caro 2009). The clear link to exposure, i.e. the shoulder height relative to habitat openness, suggested that an inability to rely on crypsis or take refuge in dense vegetation has driven the evolution of horns for defence against predators in most female bovids. Hence, weapons can also give a benefit in terms of a high dominance rank related to interference competition either for a territory or directly for food. In addition to our study, such a view is consistent with results from Soay sheep (Ovis aries), where females with larger horns were more likely to initiate and win aggressive interactions during the lambing period over access to food, and more so at high local density (Robinson and Kruuk 2007). Female Soay sheep without horns suffered from reduced longevity, and thus reduced lifetime breeding success, relative to other horn morphs (Robinson et al. 2006). Since the Soay sheep, like Svalbard reindeer, lack contemporary predators, they provide one more case where competition plays a role in the evolution of female weaponry.

References

Albon SD et al (2017) Contrasting effects of summer and winter warming on body mass explain population dynamics in a food-limited Arctic herbivore. Glob Change Biol 23:1374–1389. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13435

Andersson M (1994) Sexual selection. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Bates D, Machler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48

Bergerud AT (1976) Annual antler cycle in Newfoundland caribou. Can Field Nat 90:449–463

Bro-Jørgensen J (2007) The intensity of sexual selection predicts weapon size in male bovids. Evolution 61:1316–1326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00111.x

Clutton-Brock TH (1982) The functions of antlers. Behaviour 79:108–125

Clutton-Brock TH, Albon SD, Harvey PH (1980) Antlers, body size and breeding group size in the Cervidae. Nature 285:565–567

Clutton-Brock TH, Guinness FE, Albon SD (1982) Red deer. Behaviour and ecology of two sexes. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Clutton-Brock TH, Albon SD, Guinness FE (1988) Reproductive success in male and female red deer. In: Clutton-Brock TH (ed) Reproductive success. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 325–343

Côté SD, Festa-Bianchet M, Smith KG (1998) Horn growth in mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus). J Mammal 79:406–414. https://doi.org/10.2307/1382971

Derocher AE, Wiik O, Bangjord G (2000) Predation of Svalbard reindeer by polar bears. Polar Biol 23:675–678

Douhard M et al (2016) The influence of weather conditions during gestation on life histories in a wild Arctic ungulate. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.1760

Douhard M, Pigeon G, Festa-Bianchet M, Coltman DW, Guillemette S, Pelletier F (2017) Environmental and evolutionary effects on horn growth of male bighorn sheep. Oikos 126:1031–1041. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03799

Elvebakk A (2005) A vegetation map of Svalbard on the scale 1: 3.5 mill. Phytocoenologia 35:951–967. https://doi.org/10.1127/0340-269x/2005/0035-0951

Espmark Y (1964) Studies in dominance-subordination relationship in a group of semi-domestic reindeer (Rangifer tarandus L.). Anim Behav 12:420–426

Espmark Y (1971) Antler shedding in relation to parturition in female reindeer. J Wildl Manag 35:175–177. https://doi.org/10.2307/3799887

Fancy SG, White RG (1985) Energy expenditures by caribou while cratering in snow. J Wildl Manag 49:987–993

Festa-Bianchet M, Gaillard JM, Jorgenson JT (1998) Mass- and density-dependent reproductive success and reproductive costs in a capital breeder. Am Nat 152:367–379

Festa-Bianchet M, Coltman DW, Turelli L, Jorgenson JT (2004) Relative allocation to horn and body growth in bighorn rams varies with resource availability. Behav Ecol 15:305–312. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arh014

Geist V (1966) Evolution of horn-like organs. Behaviour 27:175–214. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853966x00155

Gould SJ (1992) Ever since darwin: reflections in natural history. Norton, New York

Hamel S, Côté SD (2009) Foraging decisions in a capital breeder: trade-offs between mass gain and lactation. Oecologia 161:421–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-009-1377-y

Hansen BB, Aanes R, Saether BE (2010) Feeding-crater selection by high-arctic reindeer facing ice-blocked pastures. Can J Zool 88:170–177. https://doi.org/10.1139/z09-130

Holand O et al (2004) Social rank in female reindeer (Rangifer tarandus): effects of body mass, antler size and age. J Zool 263:365–372. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0952836904005382

Lee A et al (2015) An integrated population model for a long-lived ungulate: more efficient data use with Bayesian methods. Oikos 124:806–816

Lefcheck JS (2016) piecewiseSEM: piecewise structural equation modelling in R for ecology, evolution, and systematics. Methods Ecol Evol 7:573–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12512

Moen RA, Pastor J, Cohen Y (1999) Antler growth and extinction of Irish elk. Evol Ecol Res 1:235–249

Mysterud A, Meisingset E, Langvatn R, Yoccoz NG, Stenseth NC (2005) Climate-dependent allocation of resources to secondary sexual traits in red deer. Oikos 111:245–252

Nordli O, Przybylak R, Ogilvie AEJ, Isaksen K (2014) Long-term temperature trends and variability on Spitsbergen: the extended Svalbard Airport temperature series, 1898–2012. Polar Res. https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v33.21349

Omsjø EH et al (2009) Evaluating capture stress and its effects on reproductive success in Svalbard reindeer. Can J Zool 87:73–85. https://doi.org/10.1139/z08-139

Packer C (1983) Sexual dimorphism: the horns of African antelopes. Science 221:1191–1193

Pinheiro JC, Bates DM (2000) Mixed-effects models in S and S-plus. Springer, New York

Prichard AK, Finstad G, Shain DH (1999) Factors affecting velvet antler weights in free-ranging reindeer in Alaska. Rangifer 19:71–76. https://doi.org/10.7557/2.19.2.282

R Core Team (2016) R: a language and environment for statistical computing, 3.3.1 edn. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Reimers E, Nordby O (1968) Relationships between age and tooth cementum layers in Norwegian reindeer. J Wildl Manag 32:957–961

Roberts SC (1996) The evolution of hornedness in female ruminants. Behaviour 133:399–442

Robinson MR, Kruuk LEB (2007) Function of weaponry in females: the use of horns in intrasexual competition for resources in female Soay sheep. Biol Let 3:651–654. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2007.0278

Robinson MR, Pilkington JG, Clutton-Brock TH, Pemberton JM, Kruuk LEB (2006) Live fast, die young: trade-offs between fitness components and sexually antagonistic selection on weaponry in Soay sheep. Evolution 60:2168–2181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01854.x

Schaefer JA, Mahoney SP (2001) Antlers on female caribou: biogeography of the bones of contention. Ecology 82:3556–3560. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082%5b3556:aofcbo%5d2.0.co;2

Schmidt KT, Stien A, Albon SD, Guinness FE (2001) Antler length of yearling red deer is determined by population density, weather and early life history. Oecologia 127:191–197

Shipley B (2016) Cause and correlation in biology : a user’s guide to path analysis, structural equations, and causal inference with R, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Skogland T (1989) Comparative social organization of wild reindeer in relation to food, mates and predator avoidance. Adv Ethol 29:1–74

Smith BL (1998) Antler size and winter mortality of elk: effects of environment, birth year, and parasites. J Mammal 79:1038–1044

Stankowich T, Caro T (2009) Evolution of weaponry in female bovids. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 276:4329–4334. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1256

Stien A et al (2012) Congruent responses to weather variability in high arctic herbivores. Biol Lett 8:1002–1005. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.0764

Thalmann JC, Bowyer RT, Aho KA, Weckerly F, McCullough DR (2015) Antler and body size in black-tailed deer: an analysis of cohort effects. Adv Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/156041

Thomas D, Barry S (2005) Antler mass of barren-ground caribou relative to body condition and pregnancy rate. Arctic 58:241–246

Tveraa T, Stien A, Bårdsen BJ, Fauchald P (2013) Population densities, vegetation green-up, and plant productivity: impacts on reproductive success and juvenile body mass in reindeer. Plos One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056450

Tyler NJC (1987) Natural limitation of the abundance of the high arctic Svalbard reindeer. PhD thesis, University of Cambridge

van der Wal R, Stien A (2014) High-arctic plants like it hot: a long-term investigation of between-year variability in plant biomass. Ecology 95:3414–3427

Vanpé C et al (2007) Antler size provides an honest signal of male phenotypic quality in roe deer. Am Nat 169:481–493. https://doi.org/10.1086/512046

Veiberg V et al (2017) Maternal winter body mass and not spring phenology determine annual calf production in an Arctic herbivore. Oikos 126:980–987. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03815

Weladji RB, Holand O, Steinheim G, Colman JE, Gjostein H, Kosmo A (2005) Sexual dimorphism and intercorhort variation in reindeer calf antler length is associated with density and weather. Oecologia 145:549–555

Wood S (2006) Generalized additive models: an introduction with R. Taylor & Francis/CRC Press, London

Acknowledgements

We thank the Governor of Svalbard for permission to undertake the research. We are especially grateful to Steve Coulson, Mads Forchhammer and the logistical and technical staff at the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) for supporting the field campaigns. The work was supported mainly by grants from U.K. Natural Environment Research Council (GR3/1083), the Norwegian Research Council (POLARPROG project 216051 and KLIMAFORSK 267613) and the Macaulay Development Trust. We are grateful to Brage B. Hansen for providing antler mass data and to Jean-Michel Gaillard, Mark Hewison and one anonymous referee for providing valuable comments that greatly improved an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding

Data will be archived on Dryad (http://datadryad.com/) following acceptance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LEL, SA, AS, JI, VV and ER managed the long-term Svalbard reindeer project, collected the data and conceived the idea for the study. GP and LEL did the analyses. LEL, AM and PEG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All applicable institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. Captures and handling of Svalbard reindeer were approved by the Norwegian Food Safety Authority (permission number 17/237024) and by the Governor of Svalbard (permission number 16/01632-9).

Additional information

Communicated by Jean-Michel Gaillard.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Loe, L.E., Pigeon, G., Albon, S.D. et al. Antler growth as a cost of reproduction in female reindeer. Oecologia 189, 601–609 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-019-04347-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-019-04347-7