Abstract

Despite the well-known role of obesity as risk factor for Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) severity, emerging but limited evidence suggested a similar role for underweight. We investigated the role of body mass index (BMI) across its full spectrum in a cohort of children with JIA.

We retrospectively studied 113 children with JIA classified according to the International League of Association for Rheumatology (ILAR) criteria attending our Rheumatology Clinic. The patients underwent a comprehensive evaluation including both clinical and biochemical assessments. According to BMI Z-score, the cohort was divided into five groups as underweight, normal weight, overweight (OW), obesity (OB), and severe OB. Disease activity was calculated by Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score 10 (JADAS-10) joint reduced count and relapses were defined according to Wallace criteria.

The mean age of the cohort was 7.43 ± 4.03 years. The prevalence of underweight, normal weight, OW, OB, and severe OB was 7.2%, 54.1%, 10.8%, 17.1%, and 10.8%, respectively. Significant higher ferritin levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate values were found in patients with severe OB and underweight compared to subjects belonging to normal weight, OW, and OB groups. A greater JADAS-10 score was observed in underweight patients and in those with severe OB than other groups. The relapse rate was higher in patients with severe OB and underweight compared to other groups.

Conclusions: Both underweight and OB might negatively affect JIA course. Weight control is fundamental in children with JIA to avoid a more unfavourable course of the disease.

What is Known: • Obesity represents a well-known risk factor for JIA severity. • The role of underweight in children with JIA is still poorly explored. | |

What is New: • As observed in children with obesity, underweight young patients with JIA seem to experience a more severe JIA course. • Healthy lifestyle promotion in children with JIA is a crucial step in the management of the disease. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) has been currently recognized as the most common chronic rheumatic disease in childhood [1] with a relevant burden including disease-specific complications and cardiometabolic consequences [2, 3]. Based on the International League of Association for Rheumatology (ILAR), seven subtypes of arthritis can be defined according to the number of joints and the extra-articular involvement occurring in the first 6 months of disease [4]. Over the last years, a significant improvement in long-term JIA outcomes has been made with the advent of new therapeutic options [5]. As the lack of guidelines for JIA treatment, therapeutic strategies for the disease have been established according to the American College of Rheumatology recommendations taking into account JIA subtypes and disease activity [6, 7]. Commonly, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and intra-articular steroids are considered as first line of treatment for oligoarticular JIA. Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are useful for systemic JIA (with prevalent joint involvement), and for polyarticular and oligoarticular JIA with moderate or high disease activity in addition to NSAIDs and intra-articular steroids [6, 7]. More, biologic drugs are used in children with systemic, polyarticular or oligoarticular JIA with moderate or high disease activity [6, 7]. In selected cases such as systemic JIA with prevalence of systemic features (e.g. fever), systemic steroids are preferred as first line treatment [6, 7].

To date, evidence supported the influence of body mass index (BMI) on JIA disease activity [8], but studies in the field across all age groups are still conflicting [8,9,10,11].

Obesity has emerged as a modifiable risk factor for JIA severity both in adults and children [8, 12], but recent intriguing data have also showed a potential effect of underweight in this context [9]. In adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), obesity has been associated with high disease activity [8], while a significant improvement in RA disease activity has been observed in these patients after weight loss [13]. Conversely, evidence regarding the influence of BMI on JIA course in children is still scarce and contrasting [8, 9].

To fill this gap, we aimed at investigating the role of BMI across its full spectrum on the course of the disease in a cohort of children with JIA.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively examined 113 children with JIA classified according to ILAR criteria [4] attending our Rheumatology Clinic between January 1999 and January 2021. Informed consent was obtained prior to any procedure. The Research Ethical Committee of our institution approved the study. Exclusion criteria were considered as follows: (i) denied consent for diagnostic procedures, (ii) missing data, (iii) non-returning at the scheduled follow-up, (iv) steroid treatment less than 12 months prior to study inclusion and/or at enrollment, and (v) other underlying diseases.

JIA treatment was administered according to the American College of Rheumatology recommendations [6]. In our center, NSAIDs and intra-articular steroids are the first line of treatment for patients with oligoarthritis. DMARDs and biologic drugs are used in children with systemic, polyarticular JIA or patient affected by oligoarthritis not responding to NSAIDs or intra-articular steroids. Patients diagnosed with systemic JIA received oral steroids for short time to induce clinical remission, while other JIA subtypes were treated with intra-articular steroid injections.

All the patients with newly diagnosed JIA return to our observation monthly until reaching clinical remission and then every 3 or 6 months depending on patient clinical conditions and treatments.

At the time of the first visit and at follow-up visits, anthropometric and laboratory data were assessed as described elsewhere [2]. Age at disease onset, disease duration, active joints involvement, presence of comorbidities, and medications were also collected. Regarding the joints selection, lower limbs and sacroiliac joints were evaluated as their well-known greater involvement in JIA subjects with obesity [8, 14].

Disease activity was assessed by Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score 10 (JADAS-10) [15] and relapses were defined according to Wallace criteria [16].

According to BMI Z-score, our cohort was divided into five categories as underweight, normal weight, overweight (OW), obesity (OB), and severe obesity [17, 18].

Differences for continuous variables were analysed with the independent-sample t test for normally distributed variables and with the Mann–Whitney test in case of non-normality. Qualitative variables were compared using the chi-squared test. Linear regression was used to investigate the association of JADAS-10 with BMI Z-score categories.

The IBM SPSS Statistics software, Version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Data were expressed as means ± SD. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

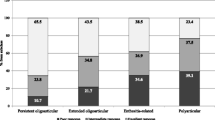

The enrolled patients showed a mean age of 7.43 ± 4.03 year. According to Tanner stage, all the subjects were prepubertal. JIA subtypes of the study population according to ILAR classification were as follows: 41% persistent oligoarticular, 9.1% extended oligoarticular, 23.6% RF-polyarticular, 8.2% Rheumatoid Factor (RF) + polyarticular, 7.3% systemic, 8.2% enthesitis-related arthritis, and 2.7% psoriatic arthritis.

The main features of the study population stratified on the basis of BMI weight status categories are reported in Table 1. The prevalence of underweight, normal weight, overweight, OB, and severe OB was 8.8%, 53.1%, 10.6%, 16.8%, and 10.6%, respectively (Table 1). Age at disease onset did not differ across groups (p = 0.74).

Patients with severe OB and underweight showed significant higher ferritin levels, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate values compared to subjects belonging to normal weight, OW, and OB groups (p = 0.02, p = 0.02 and p = 0.04, respectively). A greater JADAS-10 score was reported in underweight patients and in those with severe OB than other groups (p = 0.013) (Table 1). Children with OB and severe OB affected by JIA presented with a higher number of affected joints compared other groups (p = 0.04). Both these groups also showed a major involvement of lower limbs including sacroiliac and midfoot joints (p = 0.004 for OB and p = 0.005 for severe OB, respectively). A significant increased number of relapses was also reported in patients with severe OB and underweight compared to other categories (p = 0.02).

Discussion

In our cohort of children diagnosed with JIA, we found a dual role of BMI in terms of both underweight and obesity on disease course.

Although the role of obesity as modifiable risk factor for the severity and response to treatment has been reported both in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis and in paediatric patients with JIA [8, 19], a similar evidence for underweight is still very limited [9].

In an attempt to explain the effect of obesity on JIA, different potential pathophysiological mechanisms have been supposed [20]. In particular, robust evidence has supported the well-known mechanical role of obesity [8, 12] and its potential pro-inflammatory effect as central players in modulating JIA course [21].

Current estimates reported an increased prevalence (up to 23%) of overweight and obesity in patients with JIA [22]. This could be secondary to the lack of physical activity due to joint pain, stiffness, fatigue or other short or long-term disease-related disabilities [12, 23]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that JIA children with obesity had higher levels of inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 1 (IL-1), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF- α) than normal weight children with JIA [24, 25]. Moreover, it should be noted that low-grade inflammation represents a hallmark of obesity, as largely demonstrated [26, 27].

Indeed, the pivotal role of adipose tissue in pro-inflammatory pathways activation has been largely examined [12, 25], suggesting a pathogenic role for adipokines in explaining its potential relationship with inflammatory arthritis [25]. In this framework, robust data have demonstrated for these cell-signalling molecules (including leptin, adiponectin, visfatin, and resistin) both immunomodulatory and pathogenic effects in RA development. Indeed, mounting evidence has supported the role of adipose tissue as an active immune organ secreting various immunomodulatory factors [22, 25] including various adipokines (e.g. leptin, resistin, vaspin) and cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1 [24], which in turn might be responsible for a high disease activity in JIA patients with obesity [8, 20, 24].

On the other hand, a potential role for underweight in affecting disease activity has been also demonstrated [28]. The negative impact of underweight on the disease might be explained by hypothesising an impairment on weight gain due to active disease [9]. In fact, it could be supposed that higher chronic systemic inflammation may lead to lower BMI through reduced appetite, loss of lean mass, and increased metabolic rate [29].

The present study had some limitations that deserve mention. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow to establish causal relationships. Moreover, the small sample (although well-phenotyped) of enrolled patients, the lack of data potentially affecting BMI such as socioeconomic status, parental education level, physical activity, and nutrition, and the single-centre enrolment should be also acknowledged.

In conclusion, our findings suggested an intriguing role of weight status (both as obesity and as underweight) on JIA course in childhood. Taking into account the overall JIA burden (including disease-specific complications and cardiometabolic derangements), an accurate management of these subjects is highly recommended. In addition to the arthritis control, maintaining an adequate BMI through dietary and lifestyle interventions is of paramount importance for these patients to avoid a more unfavourable JIA course.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DMARDs:

-

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

- ILAR:

-

International League of Association for Rheumatology

- JIA:

-

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

- JADAS-10:

-

Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score 10

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- OB:

-

Obesity

- OW:

-

Overweight

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

References

Ravelli A, Martini A (2007) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet 369:767–778

Gicchino MF, Marzuillo P, Zarrilli S, Melone R, Guarino S, Miraglia Del Giudice E, Olivieri AN, Di Sessa A (2023) Uric acid could be a marker of cardiometabolic risk and disease severity in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Eur J Pediatr 182:149–154

Sule S, Fontaine K (2018) Metabolic syndrome in adults with a history of juvenile arthritis. Open Access Rheumatol 10:67–72

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, He X, Maldonado-Cocco J, Orozco-Alcala J, Prieur AM, Suarez-Almazor ME, Woo P (2004) International League of Associations for R: International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol 31:390–392

Mannion ML, Cron RQ (2022) Therapeutic strategies for treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Curr Opin Pharmacol 64:102226

Ringold S, Weiss PF, Beukelman T, DeWitt EM, Ilowite NT, Kimura Y, Laxer RM, Lovell DJ, Nigrovic PA, Robinson AB, Vehe RK (2013) American Collge of R: 2013 update of the 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: recommendations for the medical therapy of children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and tuberculosis screening among children receiving biologic medications. Arthritis Rheum 65:2499–2512

Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Cron RQ, DeWitt EM, Ilowite NT, Kimura Y, Laxer RM, Lovell DJ, Martini A, Rabinovich CE, Ruperto N (2011) 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63:465–482

Giani T, De Masi S, Maccora I, Tirelli F, Simonini G, Falconi M, Cimaz R (2019) The influence of overweight and obesity on treatment response in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Front Pharmacol 10:637

Neto A, Mourao AF, Oliveira-Ramos F, Campanilho-Marques R, Estanqueiro P, Salgado M, Guedes M, Piotto D, Emi Aikawa N, Melo Gomes J, Cabral M, Conde M, Figueira R, Santos MJ, Fonseca JE, Terreri MT, Canhao H (2021) Association of body mass index with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis disease activity: a Portuguese and Brazilian collaborative analysis. Acta Reumatol Port 46:7–14

Guzman J, Kerr T, Ward LM, Ma J, Oen K, Rosenberg AM, Feldman BM, Boire G, Houghton K, Dancey P, Scuccimarri R, Bruns A, Huber AM, Watanabe Duffy K, Shiff NJ, Berard RA, Levy DM, Stringer E, Morishita K, Johnson N, Cabral DA, Larche M, Petty RE, Laxer RM, Silverman E, Miettunen P, Chetaille AL, Haddad E, Spiegel L, Turvey SE, Schmeling H, Lang B, Ellsworth J, Ramsey SE, Roth J, Campillo S, Benseler S, Chedeville G, Schneider R, Tse SML, Bolaria R, Gross K, Feldman D, Cameron B, Jurencak R, Dorval J, LeBlanc C, St Cyr C, Gibbon M, Yeung RSM, Duffy CM, Tucker LB (2017) Growth and weight gain in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the ReACCh-Out cohort. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 15:68

Caetano MC, Sarni RO, Terreri MT, Ortiz TT, Pinheiro M, de Souza FI, Hilario MO (2012) Excess of adiposity in female children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 31:967–971

Held M, Sestan M, Jelusic M (2022) Obesity as a comorbidity in children and adolescents with autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int

Kreps DJ, Halperin F, Desai SP, Zhang ZZ, Losina E, Olson AT, Karlson EW, Bermas BL, Sparks JA (2018) Association of weight loss with improved disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective analysis using electronic medical record data. Int J Clin Rheumtol 13:1–10

Vennu V, Alenazi AM, Abdulrahman TA, Binnasser AS, Bindawas SM (2020) Obesity and multisite pain in the lower limbs: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Pain Res Manag 2020:6263505

Ravelli A, Consolaro A, Horneff G, Laxer RM, Lovell DJ, Wulffraat NM, Akikusa JD, Al-Mayouf SM, Anton J, Avcin T, Berard RA, Beresford MW, Burgos-Vargas R, Cimaz R, De Benedetti F, Demirkaya E, Foell D, Itoh Y, Lahdenne P, Morgan EM, Quartier P, Ruperto N, Russo R, Saad-Magalhaes C, Sawhney S, Scott C, Shenoi S, Swart JF, Uziel Y, Vastert SJ, Smolen JS (2018) Treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 77:819–828

Wallace CA, Ruperto N, Giannini E, Childhood A, Rheumatology Research A (2004) Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials O, Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study G: preliminary criteria for clinical remission for select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 31:2290–2294

Freedman DS, Berenson GS (2017) Tracking of BMI z scores for severe obesity. Pediatrics 140

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J (2007) Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 85:660–667

Merwin S, Mackey E, Sule S (2021) US NHANES Data 2013–2016: increased risk of severe obesity in individuals with history of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 19:119

Diaz-Cordoves Rego G, Nunez-Cuadros E, Mena-Vazquez N, Aguado Henche S, Galindo-Zavala R, Manrique-Arija S, Martin-Pedraz L, Redondo-Rodriguez R, Godoy-Navarrete FJ, Fernandez-Nebro A (2021) Adiposity is related to inflammatory disease activity in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. J Clin Med 10

Schulert GS, Graham TB (2014) Chronic inflammatory arthritis of the ankle/hindfoot/midfoot complex in children with extreme obesity. J Clin Rheumatol 20:317–321

Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB (2001) Low-grade systemic inflammation in overweight children. Pediatrics 107:E13

Sandstedt E, Fasth A, Eek MN, Beckung E (2013) Muscle strength, physical fitness and well-being in children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and the effect of an exercise programme: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 11:7

MacDonald IJ, Liu SC, Huang CC, Kuo SJ, Tsai CH, Tang CH (2019) Associations between adipokines in arthritic disease and implications for obesity. Int J Mol Sci 20

Derdemezis CS, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA, Kiortsis DN (2011) Obesity, adipose tissue and rheumatoid arthritis: coincidence or more complex relationship? Clin Exp Rheumatol 29:712–727

Halle M, Korsten-Reck U, Wolfarth B, Berg A (2004) Low-grade systemic inflammation in overweight children: impact of physical fitness. Exerc Immunol Rev 10:66–74

Tam CS, Clement K, Baur LA, Tordjman J (2010) Obesity and low-grade inflammation: a paediatric perspective. Obes Rev 11:118–126

Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Metsios GS, Panoulas VF, Nevill AM, Jamurtas AZ, Koutedakis Y, Kitas GD (2009) Underweight and obese states both associate with worse disease activity and physical function in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 28:439–444

Bout-Tabaku S (2018) General nutrition and fitness for the child with rheumatic disease. Pediatr Clin North Am 65:855–866

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all patients and their families.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MFG and ADS drafted the paper. EMDG, ANO, and ADS participated in the conception and the design of the study. SZ, RM, and PM examined the patients and collected anthropometric and biochemical data. ADS, MFG, and PM performed data analysis. ADS, EMDG, ANO, and PM supervised the design and execution of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Research Ethical Committee of University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” (protocol code 834/2016).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Patients’ data were treated to guarantee confidentiality.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Peter de Winter

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gicchino, M., Marzuillo, P., Melone, R. et al. The dual role of body mass index on Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis course: a pediatric experience. Eur J Pediatr 183, 809–813 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05348-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05348-8