Abstract

Pagetoid spread in esophageal squamous epithelium associated with underlying esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has been well studied. Case reports describing pagetoid spread of esophageal squamous cell carcinomas (ESCC) also exist in the literature. The latter, however, has not been systematically studied. In this study, we report seven cases of pagetoid spread associated with ESCC. The clinical, morphologic, and immunophenotypic profiles of pagetoid spread in the context of ESCC and EAC are compared. Cases of pagetoid spread of ESCC were identified through computerized search of pathology archives at five institutions. Additional cases were identified through manual review of surgical resection cases of treatment naive ESCC in Mass General Brigham (MGB) pathology archive. Clinical history was collected via chart review. Immunohistochemistry for CK7, CK20, CDX2, p53, p63, and p40 was performed on selected cases. A computerized search of pathology archives of five institutions revealed only two cases. A manual review of 76 resected untreated ESCC revealed five additional cases with unequivocal pagetoid spread of ESCC, indicating the condition was not uncommon but rarely reported. Patient age ranged from 54 to 78 years (median, 65). There were six women and one man. One case had in situ disease, five had pT1 (1 pT1a and 4 pT1b), and one had pT3 disease. One of the patients with pT1 tumor had a positive lymph node, while the remaining six patients were all N0. Four tumors were in the proximal to mid esophagus, and three in the distal esophagus. Patient survival ranged from 25 months to more than 288 months. The pagetoid tumor cells demonstrated enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with variable amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cytoplasm was often condensed to the perinuclear area, creating peripheral clearing. By immunohistochemistry, the pagetoid cells were positive for p40 (6/6) and p63 (7/7) and negative for CDX2 (7/7). The tumor cells showed mutant-type staining for p53 in five of seven cases. One of the patients had pagetoid tumor cells at the resection margin and subsequently had recurrent disease 2 years later. All other patients had negative resection margins and did not have local recurrence. Four cases of pagetoid spread in the context of EAC were used as a comparison group. Previously published studies were also analyzed. These tumors were all located in the distal esophagus or gastroesophageal junction. All cases were associated with underlying invasive EAC. Pagetoid spread associated with EAC often had cytoplasmic vacuoles or mucin. They were more frequently positive for CK7 than pagetoid ESCC (p = 0.01). Both ESCC and EAC may give rise to pagetoid spread of tumor cells within surface squamous epithelium. Pagetoid spread from ESCC and EAC have overlapping morphologic features. P40 and p63 immunostains can facilitate the distinction between ESCC and EAC. P53 immunostain can aid in confirmation of malignancy. Understanding their overlapping pathologic features will help pathologists avoid pitfalls and diagnose these lesions correctly on biopsy specimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) of the esophagus is rare and includes two forms: primary and secondary. Primary Paget disease is challenging to diagnose, and there are only a handful of potential cases reported in the literature [1,2,3,4]. Secondary Paget disease is caused by intra-epithelial spreading of malignant cells from an underlying internal malignancy. It is often phrased as “pagetoid spread” in pathology reports. The most common and better understood neoplasm that demonstrates intra-epithelial spread is esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Abraham et al. [5] reported that after screening all endoscopic biopsies, endoscopic mucosal resection and surgical resections in a 13-year timespan (from 1994 to 2007), no primary Paget disease of the esophagus was identified. Instead, all cases containing Paget cells (5 cases) represented secondary extension from underlying invasive adenocarcinoma. It was also the authors’ anecdotal experience that pagetoid tumor cells encountered in esophageal biopsies are almost always from an underlying adenocarcinoma. We recently encountered a case of pagetoid spread of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), which shares morphologic resemblance to that of EAC. In this report, we set out to determine the prevalence of pagetoid spread of ESCC and the immunohistochemical profile of these tumor cells as they may be mistaken as EAC or other entities and can be a pitfall of misdiagnosis.

Methods

Two approaches were used to determine the prevalence of pagetoid spread of squamous cell carcinoma. First, a systematic search of pathology archives using the phrases “pagetoid” (or “Paget”) and “squamous cell carcinoma” and “esophagus” was performed at five participating institutions. To establish a control group, a systematic search using the phrases “pagetoid” (or “Paget”) and “adenocarcinoma” and “esophagus” was also performed. For all search hits, clinical history was collected through electronic chart review. Histologic slides were retrieved and reviewed. Due to the paucity of search hits, a manual review of 76 surgical resections of treatment naive squamous cell carcinoma was performed.

Paraffin-embedded tissue of selected blocks was retrieved, and immunohistochemistry for p53 (1:500; DAKO), CK7 (1:1000; DAKO), CK20 (1:50; DAKO), CDX2 (1:150; BioGenex), p40 (1:250; BioCare), and p63 (1:150; BioCare) was performed.

Chi-square was used for statistical analysis. A p value (two-tailed) less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of participating institutions.

Results

Prevalence and clinical characteristics of pagetoid spread of squamous cell carcinoma

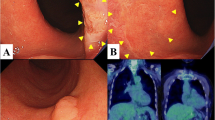

A systematic search of pathology archives from 2010 to 2020 at five institutions revealed two documented cases of pagetoid spread of ESCC (case 1 and 2, Table 1 and 2, Fig. 1, and Supplemental Fig. 1) (case 2 previously published [6] but now with additional follow-up data). Four cases of pagetoid spread of underlying esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) were identified using a similar approach during the same time period.

A systematic review of 76 resected untreated ESCC from MGB pathology archives revealed five additional cases (case 3–7) (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Fig. 1) with unequivocal pagetoid spread of ESCC, indicating that the condition was not uncommon, but was rarely documented.

Patient age ranged from 54 to 78 years (median, 65). There were six women and one man. One case had in situ disease, five had pT1 (1 pT1a and 4 pT1b), and one had pT3 disease. One of the patients with pT1 tumor had a positive lymph node, whereas the remaining six patients were all N0. Four tumors were in the proximal to mid esophagus and three in the distal esophagus. Patient survival months ranged from 25 months to more than 288 months. One of the patients had pagetoid tumor cells at the resection margin and subsequently had recurrent disease 2 years later. All other patients had negative resection margins and did not have local recurrence.

Histopathologic features

The seven cases that were included in the study all demonstrated individual or small clusters of malignant tumor cells spreading within esophageal squamous epithelium, without direct connection with the main tumor. The involved epithelium was often adjacent to (within 1 cm) or overlying the main tumor, except for cases 1 and 2. In case 1, the recurrent disease presented as intraepithelial spreading only and was extensive by endoscopic examination (more than 5 cm in length). For case 2, the disease was in situ only and spanned 9 cm in total. The pagetoid tumor cells demonstrated enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with variable amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cytoplasm was often condensed to the perinuclear area, creating peripheral clearing. By immunohistochemistry, the pagetoid cells were positive for p40 (6/6) and p63 (7/7) and negative for CDX2 (7/7). One of six cases showed CK7 positivity while another case showed CK20 positivity. The tumor cells showed mutant-type staining for p53 in five of seven cases (Table 2).

Four cases of pagetoid spread in the context of EAC were used as a comparison group. These tumors were all located in the distal esophagus or GE junction. All cases were associated with underlying invasive EAC. Pagetoid spread associated with EAC often had cytoplasmic vacuoles or mucin. The tumor cells were positive for CK7 and MOC31 (in one case with available immunohistochemical study) and negative for CK5, p40, and/or p63 (in three cases with available immunohistochemical study).

A comprehensive immunophenotypic profile of pagetoid cells in the setting of EAC has been reported previously (Table 3) [5]. Pagetoid tumor cells in EAC were more commonly CK7 positive (p = 0.0121). They also showed a higher frequency of CK20 positivity, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.156). P53 expression patterns were abnormal in most Paget cells in ESCC (6 of 7) and were often observed in EAC as well (4 of 7).

Discussion

In this study, we identified seven cases of pagetoid spread of ESCC, including one case of in situ disease only and six cases of invasive disease. It is worth noting that a systematic search of electronic pathology archives at five institutions only revealed two cases, although a manual review of 76 cases of resected ESCC revealed five additional cases (6.5%). This suggests that pagetoid spread of ESCC is not uncommon but is not generally reported. The pagetoid tumor cells were all within 1 cm from the main tumor, but this could be due to sampling, as mucosa away from the main tumor is often not extensively sampled.

ESCC can involve the epithelium through two main mechanisms: intraepithelial neoplasia or lateral/intraepithelial spread. Squamous intraepithelial neoplasia represents an in situ neoplasm confined to the epithelial layer without involvement of deeper layers of the esophageal wall. In contrast, lateral spread or intraepithelial spread of ESCC represents a unique form of tumor invasion. Tumor cells exhibiting lateral spread travel horizontally along the surface epithelium or ducts of submucosal glands, without breaching the basement membrane [7].

Lateral spread or intraepithelial spread has been classified into three subtypes [8]: “total layer type” (the entire epithelium is replaced by tumor cells), “basal layer type” (only basal half of the epithelium is replaced by tumor cells), and mixed type (showing a combination of both patterns).

Pagetoid spread reported in this study refers to individual or small clusters of tumor cells spread discontinuously along the epithelium. This would be another unique subtype of “intraepithelial spread.”

The pagetoid tumor cells associated with ESCC show a high degree of morphologic similarities with those of EAC. They demonstrate enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with variable amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. The presence of cytoplasmic clearing in some of the cases may mimic mucin vacuoles. By immunohistochemistry, pagetoid SCC is p40 and p63 positive, but they can be CK7 or CK20 in rare examples, which may lead to misdiagnosis of EAC. P53 often shows an abnormal staining pattern in pagetoid tumor cells. Although it is not useful in distinguishing between SCC or EAC, it can be helpful to confirm the neoplastic nature of these cells.

The prognostic value of pagetoid spread of ESCC is unclear. In the study, survival ranged from 25 months to more than 288 months. There are too few reported cases to evaluate whether this feature correlates with long-term survival since it likely poses difficulty for endoscopic evaluation and histologic diagnosis.

Like Bowen’s disease of the skin, pagetoid spread of in situ ESCC can occur and has been reported in the literature [6, 9] (Table 4). We also identified a case from systematic review of computerized archives in this series. All reported cases (3 from literature and 1 reported here) were from female patients, and the disease involved proximal esophagus in one patient, and the mid and lower esophagus in two.

Primary Paget disease is exceedingly rare, with only four possible cases reported in the literature [1,2,3,4]. EMPD (both primary and secondary forms) more commonly involves skin or mucosa with apocrine gland, such as the genital skin, axillae, and anus [10, 11]. Primary EMPD is an intraepithelial tumor that possibly arises from the epidermis or apocrine glands. Primary EMPD can occasionally become invasive and/or metastasize. It is postulated that the precursor cells may be a pluripotent progenitor epidermal cell or adnexal cell. By definition, primary Paget cells are of glandular origin; they are CK7 positive and CK20 negative, with expression of gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15). HER2, overexpressed in 70–100% of mammary Paget disease, shows significant variability in EMPD [12]. The esophagus contains submucosal glands, not unlike the perianal gland of the anus. It is reasonable to speculate that the secondary Paget cells likely spread to the epithelium through the submucosal gland ducts, whereas primary Paget disease arises from the intraepithelial portion of the submucosal gland. All four reported primary Paget disease of the esophagus presented as non-mass forming mucosal lesions, with two demonstrating ring-like scarring similar to eosinophilic esophagitis.

In addition to primary Paget disease of the esophagus and pagetoid spread of EAC, the differential diagnoses of pagetoid spread of ESCC mainly include amelanotic mucosal melanoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis [13], and mycosis fungoides [14], which can potentially be mistaken for EMPD at other anatomic sites, but are exceedingly rare.

While acknowledging the limitations imposed by the study’s small size, primarily due to the lower incidence of ESCC in North America, it is important to note that pagetoid spread of ESCC can be easily mistaken for pagetoid spread of EAC, a more prevalent type of esophageal cancer in this region. Therefore, recognizing this lesion will assist pathologists in avoiding a diagnostic pitfall.

In summary, both ESCC and EAC may give rise to pagetoid spread of tumor cells within the surface squamous epithelium. Pagetoid spread from ESCC and EAC has overlapping histologic features. P40 and p63 immunostains can facilitate the distinction between ESCC and EAC. P53 immunostain can aid in the confirmation of malignancy. Understanding their overlapping pathologic features will help pathologists avoid pitfalls and diagnose these lesions correctly on biopsy specimens.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lin DL, Liu J, Yang Z et al (2019) Esophageal invasive acantholytic anaplastic Paget’s disease: report of a unique case. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 12 (6):2293–2297

Mori H, Ayaki M, Kobara H et al (2017) Rare primary esophageal Paget’s disease diagnosed on a large bloc specimen obtained by endoscopic mucosal resection. J Gastrointest Liver Dis 26:417–420. https://doi.org/10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.264.pag

Nonomura A, Kimura A, Mizukami Y et al (1993) Paget’s disease of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol 16:130–135. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004836-199303000-00010

Matsukuma S, Aida S, Shima S, Tamai S (1995) Paget’s disease of the esophagus. A case report with review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 19:948–955. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199508000-00011

Abraham SC, Wang H, Wang KK, Wu T-T (2008) Paget cells in the esophagus: assessment of their histopathologic features and near-universal association with underlying esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 32:1068–1074. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e318160c579

Chu P, Stagias J, West AB, Traube M (1997) Diffuse pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the esophagus: a case report. Cancer 79:1865–1870

Takubo K, Takai A, Takayama S et al (1987) Intraductal spread of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 59:1751–1757. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19870515)59:10%3c1751::AID-CNCR2820591013%3e3.0.CO;2-I

Takubo K (2009) Pathology of the esophagus: an atlas and textbook, 2nd edn. Springer, Tokyo

Chen IY, Bartell N, Ettel MG (2022) Diffuse pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the esophagus: a rare case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Pathol 30:326–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/10668969211046814

Simonds RM, Segal RJ, Sharma A (2019) Extramammary Paget’s disease: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol 58:871–879. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.14328

St. Claire K, Hoover A, Ashack K, Khachemoune A (2019) Extramammary Paget disease. Dermatol Online J 25. https://doi.org/10.5070/D3254043591

van der Linden M, Meeuwis KAP, Bulten J et al (2016) Paget disease of the vulva. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 101:60–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.03.008

Matsuoka Y, Iemura Y, Fujimoto M et al (2021) Upper gastrointestinal langerhans cell histiocytosis: a report of 2 adult cases and a literature review. Int J Surg Pathol 29:550–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066896920964566

Redleaf MI, Moran WJ, Gruber B (1993) Mycosis fungoides involving the cervical esophagus. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 119:690–693. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1993.01880180110022

Liu X, Zhang D, Liao X (2023) Paget cells of the esophagus: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 10 cases. Pathology - Research and Practice 242:154345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2023.154345

Yada S, Sasaki S, Tokuno K et al (2022) Gastrointestinal: extramammary Paget disease of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 37:419–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.15665

White H, George S, Gossage J, Chang F (2019) Esophageal Paget’s disease secondary to hypopharyngeal carcinoma: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer 50:625–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-018-0087-2

Sano A, Sakurai S, Komine C et al (2018) Paget’s disease derived in situ from reserve cell hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia, and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: a case report. Surg Case Rep 4:81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-018-0489-1

Haleem A, Kfoury H, Al Juboury M, Al Husseini H (2003) Paget’s disease of the oesophagus associated with mucous gland carcinoma of the lower oesophagus. Histopathology 42:61–65. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01514.x

Karakök M, Aydın A, Sarı İ et al (2002) Paget’s disease of the esophagus. Dis Esophagus 15:334–335. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2050.2002.00266.x

Suárez Vilela D, IzquierdoGarcía F, Alonso Orcajo N (1997) Squamous carcinoma of the esophagus with extensive pagetoid dissemination. Gastroenterol Hepatol 20:360–362

Norihisa Y, Kakudo K, Tsutsumi Y et al (1988) Paget’s extension of esophageal carcinoma. Immunohistochemical and mucin histochemical evidence of Paget’s cells in the esophageal mucosa. Acta Pathol Jpn 38:651–658. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1827.1988.tb02337.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TRM and LZ designed the study. TRM, XZ, HMK, SL, NS, LY, MW, VD, JLH, MSR, and LZ collected the data. TRM and LZ analyzed the data. TRM and LZ drafted the manuscript. TRM, XZ, HMK, NS, MW, JLH, and LZ revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

TRM, XZ, HMK, SL, NS, LY, MW, MSR, and LZ have no relevant disclosures. VD serves on the Scientific advisory boards of Incyte and Viela and receives research support from Advanced Cell Diagnostic and Agios. JLH is a consultant to Aadi Bioscience, TRACON Pharmaceuticals, Adaptimmune, and Leica Biosystems.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, T.R., Zhang, X., Ko, H.M. et al. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with pagetoid spread: a clinicopathologic study. Virchows Arch (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-024-03788-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-024-03788-7