Abstract

Most patients with bladder carcinoma are diagnosed with non-muscle-invasive disease, stage Ta, and pT1. Stage remains as the single most important prognostic indicator in urothelial carcinoma. Among the pT1 bladder cancer patients, recurrence and progression of disease occur in 50% and 10%, respectively. The identification of high-risk patients within the pT1 subgroup remains an important clinical goal and an active field of research. Substaging of pT1 disease has been claimed as important histologic discriminator by the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the genitourinary tract tumors and by the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual supporting its implementation in clinical practice. Interobserver variation in pT1 diagnosis and the associated pitfalls in pT1 assessment are the critical pathological issues. The aim of this review paper is to provide the practicing pathologist with the state of the art of morphological and immunohistochemical features useful for the diagnosis of early invasive bladder carcinomas, including practical clues on how to avoid relevant interpretative pitfalls, and to summarize the current status of pT1 substaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pathologic stage is a critical determinant in bladder cancer management and prognostication. As in other hollow organs, tumor (T) stage categories in the bladder are defined by the extent of cancer invasion through its wall. Currently, pT1 tumors are malignant epithelial neoplasia invading the sub-epithelial connective tissue of the lamina propria, beyond the basement membrane, but not the muscularis propria (MP) [1, 2].

In the past, pT1 tumors have been grouped under the heading of superficially bladder carcinoma or non-muscle invasive bladder carcinoma (NMIBC) along with low-grade papillary tumors confined to the mucosa without invading the lamina propria (Ta LG) and flat high-grade (HG) tumors confined to the mucosa or carcinoma in situ (CIS), classified as Tis. However, clinical and molecular data have shown strong differences between the low-grade bladder cancer patients and high-grade carcinoma bladder patients [3,4,5,6]. At the current time, NMIBC and superficially bladder carcinoma are obsolete terms.

Different behavior has been reported within the pT1 bladder cancer group. The need to substage pT1 disease comes from clinical analysis since recurrence of disease occurs in about 50% of NMIBC patients and approximately 10% patients develop progression to muscle-invasive disease in 5 years after diagnosis [7]. Some studies have shown improved survivals in patients with pT1 lesions treated with immediate cystectomy, while others have reported no benefit [8,9,10,11]. Although pT1 bladder carcinomas are heterogeneous in terms of outcome, current guidelines for pT1 carcinoma do not discriminate between different levels of lamina propria invasion [12]. Thus, the identification of high-risk patients within the pT1 group is of great interest to both pathologists and clinicians [11, 13,14,15,16,17].

In this review paper, we aim to analyze the current criteria for a differential diagnosis in order to avoid the pitfalls in the early invasion assessment of bladder cancer and to increase the reproducibility of pT1 stage diagnosis between pathologists. An update of the substaging issue and the prognostic value of the variants that may be present in pT1 high-grade bladder cancers have been also discussed.

Current criteria for the diagnosis

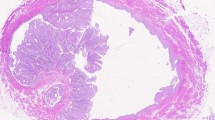

The challenging assessment of lamina propria invasion of papillary urothelial carcinoma (UC) should be based on strict criteria. The evaluation of lamina propria-epithelial interface and the morphologic appearance of the basement membrane and the characteristics of the invading epithelium with the lamina propria modification are the key points in the assessment of pTa or pT1 stage bladder carcinoma; the knowledge of the specific features of the bladder tumors may help in the diagnosis (Table 1). Non-invasive papillary tumors show a plain and regular lamina propria-epithelial interface (Fig. 1). When the specimen includes tangential sections through non-invasive disease or in case of tumor involving the von Brunn’s nests, the basement membrane shows a blunt border: high magnification permits to observe the presence of a continuous basement membrane. Contrarily, the invading epithelium may show single cells or irregularly shaped nests of tumor within the lamina propria with random arrangement without basement membrane, or the invasive front of the tumor may show finger-like extensions arising from the base of the papillary tumor (Fig. 2). In many cases, the invading nests appear with a higher degree of nuclear pleomorphism in comparison to the non-invasive tumor cells; in some cases, the invasive tumor cells may acquire abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Uncommon finding appears at low-to-medium power magnification, when the microinvasive cells seem to be more differentiated than the non-invasive component, a feature known as paradoxical differentiation (Fig. 3).

Unlike cases with extensive and unquestionable lamina propria invasion where single tumor cells and variable-sized and irregularly-shaped nests causing a stromal fibrous reaction are common features (Fig. 4), microinvasive diseases rarely show inflammatory, hypocellular stroma with myxoid background, or fibrous stromal reactions. In the majority of the cases, microinvasive UC does not cause a stromal response.

Early features of invasion into lamina propria may be a retraction artifact around superficially invasive tumor cells mimicking a lymphovascular space invasion (Fig. 5) and a strong proliferation of fibroblasts with no expansive features around the invasive component of the tumor.

Invasive tumor cells can be present at the base of the connective tissue, and also, in some cases only, in a papillary stalk. Stalk invasion is characterized by the presence of single cells or irregular tumor nests confined to the edematous connective tissue of a papillary stalk (Fig. 6).

UC with inverted growth is characterized by broad-front growth or broad bulbous tongues of urothelial tumor extending into lamina propria, with smooth basement membrane. Inverted growth should not be misdiagnosed as pT1. The invasion of lamina propria, both for papillary exophitic and inverted growth carcinomas, is assessed when there are irregularities of the basement membrane, or retraction artifact, or desmoplasia or other findings suggestive for lamina propria invasion.

Pitfalls in early invasion assessment

The diagnosis of lamina propria invasion by UC is often difficult, as also attested by the numerous studies on the interobserver differences in staging of superficial UC [18,19,20,21,22,23,24] (Table 2).

This critical issue has been addressed in a study in which 63 tumors originally diagnosed as stage pT1 have been down-staged to pTa tumors in 56% of the cases and up-staged to pT2-pT3 tumors in 13% of the cases after a consensus diagnosis by experienced genitourinary pathologists. Disease progression was more common in the 20 cases with a consensus confirmed stage pT1 (25% progression diseases) when compared to the original pT1 cases (20% progression disease). In addition, tumors that were down-staged to pTa showed less frequent progression than the stage pT1 tumors confirmed when reviewed (17% versus 25%) [19].

The pitfall in the assessment of bladder carcinoma between non-invasive and early invasive bladder cancer remains subject of considerable interobserver variation. Therefore, a group of expert uropathologists has aimed to generate a teaching set of images [21].

Table 3 lists the more common pitfalls in early assessment of bladder carcinoma invasion: the knowledge of pitfalls in early assessment of lamina propria invasion may improve the concordance rates among pathologists.

Tangential sectioning and poor orientation

Papillary tumors, usually characterized by complex architecture, are usually excised in fragments and sectioned in multiple planes; consequently, they are poorly oriented during embedding. This may cause the presence of tumor nests within connective tissue of lamina propria. Diagnosis of stromal invasion should be only done in presence of single-tumor cells and nests with irregular shape and size, without the presence of basement membrane (Fig. 7). On the other hand, the presence of regular shape, with smooth and plain margins and the presence of basement membrane encourages the Ta stage diagnosis.

Obscuring inflammation

The presence of inflammatory infiltrate may obscure the presence of single-tumor cells infiltrating the lamina propria. In this case, the staining with anti-cytokeratin antibodies may help in identifying the presence of single cells or small tumor nests (Fig. 8).

Cautery artifacts

Cautery artifacts produce distorted morphology in TURBT specimens, which may cause a potential pitfall for the pathologist, especially when tumor involves the von Brunn’s nests. In some cases, the use of immunohistochemistry with anti-cytokeratin antibodies may be of help in the diagnosis. CIS involving von Brunn’s nests may mimic lamina propria invasion. This is especially problematic when von Brunn’s nests are prominent or when they have been distorted by inflammatory or cautery artifact.

Type of muscle invasion

The involvement of muscle fibers by invasive tumors may be a critical source of pitfalls in the staging of bladder tumor. The presence of a desmoplastic response, inflammation, and hypertrophy of the muscle fibers may make difficult the differential diagnosis between the muscle fibers from muscularis mucosa (MM) or MP. This distinction is critical, as MP invasion is currently regarded as the cutoff for being out conservative management and aggressive therapy. MM bundles hypertrophy can be difficult to distinguish from MP, especially in TURBT specimens. Hyperplastic MM is seen in about 50% of bladder sections, being most abundant in the dome (70%) and least in the trigone [25, 26]. MM is often not discernible at the trigone [15]. In addition, the problems in diagnosis come out from the matter that hyperplastic MM, which frequently has random outline distinguishable from MP, may have compact parallel muscle fibers and regular outline closely resembling the MP [15, 26].

Moreover, invasive tumors may cause hypertrophy of stromal myofibroblasts. Cellular stroma with spindled fibroblasts and desmoplastic response may resemble muscle fibers. These features may be the cause of over-staging to T2. On the other hand, an exuberant proliferation of fibroblasts, which may display alarming cellular atypia, should not be mistaken for the spindle cell component of a sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma. The proliferating stroma is limited to areas around the neoplasm and is composed of cells which have a predominant degenerate or smudged appearance [27].

Immunostaining with smoothelin has been proposed to distinguish MM and MP: several studies have demonstrated the unequal staining in MM (usually weak or absent) versus MP (usually strong) with smoothelin [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. In addition, smoothelin does not stain subepithelial myofibroblasts and desmoplasia, and MP staining is preserved in cauterized tissue in most of the cases [33, 34].

However, overlap in staining of MM and MP may occur sometimes and discrimination in TURB specimens becomes problematic, particularly when staining is modest and without both muscle types present as internal reference [32]. Staining intensity may also vary with titration and antigen retrieval techniques [30, 35]. Other muscle markers such as desmin and caldesmon do not show unequal staining in MM and MP although they may be used to highlight the muscle and allow the differential diagnosis with subepithelial myofibroblasts and desmoplastic response [31, 34]. The 2013 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) conference on best practice recommendation in the application of immunohistochemistry recognized the limitations of smoothelin precluding its routine use [28]. According to our experience, smoothelin stain can differentiate MM from MP, while desmin may give an important help in the differential diagnosis between myofibroblasts/desmoplastic reaction and MM/MP, even though it is not useful in the distinction between MM and MP (Fig. 9). The clinical information of the exact site of the TURB specimen associated with the knowledge of the topographic variation may further implement the correct sub-staging [36, 37].

Diagnosis of pT1 bladder carcinoma arising in a diverticulum is made when tumor involves the connective tissue underneath urothelium (Fig. 10). In the majority of the cases of acquired diverticula, few muscle fascicles may be identified in the connective tissue; however, in some cases, they become hyperplastic until they look like a continuous layer of smooth muscle. In acquired diverticula, a true MM is lacking. Presence of tumor cells beyond the connective tissue, invading the peri-diverticular soft tissue, should be staged as pT3.

Iatrogenic change of the urinary bladder: radiation therapy

Radiation therapy for pelvic cancers may cause variable morphologic alterations in the bladder wall such as acute and chronic radiation cystitis, mucosal ulceration and denudation, and late fibrosis with bladder contracture. In addition, it induces cellular and nuclear enlargement, frequent multinucleation, and vacuolization with low nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio bringing on difficulties in differential diagnosis with pseudo-tumoral findings (Fig. 11). Histological features such as proliferative and pseudo-infiltrative urothelial nests within the stroma, called pseudo-carcinomatous hyperplasia, may be related to a previous history of radiation or other chronic injuries. Pseudo-carcinomatous hyperplasia should be differentiated from invasive urothelial carcinoma and the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. The presence of background therapy-related changes, such as dilated thrombosed vessels, edema, reactive-appearing endothelial and stromal cells, and hemorrhage, can help in distinguishing pseudo-carcinomatous hyperplasia from carcinoma. The known previous history of radiation therapy is essential. The expression of p53, CD44, and CK20 could be of help since it is similar to what is seen in reactive urothelium [38, 39].

Variants of urothelial carcinoma with misleading features

The recognition of variants in pT1 samples may be more difficult compared to the advanced cases, not only because some variants may be under-recognized due to the frequent interobserver variability but also for the pitfalls of early assessment of some uncommon variants such as nested-type carcinoma, micropapillary carcinoma, large nested type, or microcystic carcinoma. Additionally, the differential diagnosis between these unusual variants and benign proliferative urothelial lesions, such as von Brunn’s nests, inverted papilloma, and nephrogenic metaplasia which manifest as pseudo-invasive nests of urothelium within the lamina propria, can be a diagnostic challenge [40] (Fig. 12).

pT1 substaging

Known prognostic factors in pT1 tumors include grade, tumor size, CIS, multiplicity, and recurrence [12]. Substaging helps further stratify pT1 tumors, and its use is gaining reception in pathology practice, although the approach still has to be standardized. In a 2008 European Network of Uropathology (ENUP) survey, 37% of pathologists performed substaging mostly (68%) by using the MM [41]. While the 2016 8th edition AJCC recognizes that pT1 substaging is not yet optimized, it nevertheless strongly recommends attempting its use [1, 15,16,17]. The 2016 WHO “blue book” also suggested that pT1 substaging is clinically relevant [2]. The 2012 International Consultation on Urological Diseases (ICUD)-European Association of Urology (EAU) International Consultation on Bladder Cancer panel recommended pathologists to provide an estimate of LP involvement [42]. Most recently, the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting (ICCR) suggests using either depth or dimension of invasion or using MM for pT1 subcategorization [43].

The description of the presence of the MM in the bladder led to consider it as a landmark for more precise staging of bladder carcinoma [44]. When there is lamina propria invasion, the tumor may be within the muscularis mucosae or to overcome the muscularis mucosae and lap (or lick) the MP. In every case, the presence or absence of MP within the transurethral resection specimen should be reported.

In 1990, Younes and coworkers suggested to substage the pT1 bladder carcinoma according to the level of invasion of the lamina propria, defining pT1a stage when the invasion of connective tissue was superficial to the level of MM, pT1b when the invasion was at the level of MM, and pT1c when the invasion of the tumor was throughout the level of the MM but above the MP. The authors found a 75% all-cause 5-year survival for patients with pT1a and pT1b tumors invading above and into the MM, compared to an 11% survival for those tumors invading below the MM (pT1c) [45]. This substaging has been also encouraged by other authors [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

However, the main problem with this method of substaging pT1 urothelial carcinomas is that the MM is not a consistent histologic finding in all bladder specimens. Most authors have at least partially overcome this problem by using the large blood vessels in the submucosa as a substitute anatomic landmark when MM bundles are not present [37]. But, in many cases, substaging cannot be performed, because the vessels are not identified in the TURB specimen.

Carcinoma in situ with microinvasion was firstly defined by Farrow et al. in case of invasive component measuring less than 5 mm in depth [55]. Later, Amin and coworkers have reduced the cut-off for this diagnosis to 2 mm [56]. A proposal based on the Ancona International Consultation by Lopez-Beltran has suggested a cut-off of no more than 20 invading cells, measured from the lamina propria-epithelial interface, for the diagnosis of flat microinvasive disease [57]. In the last decade, several pathologists tried to formulate new histologic criteria to better define the bladder tumor staging particularly the pT1 sub-staging.

Table 4 reviews previous reports on depth of lamina propria involvement as a prognostic factor for disease progression in pT1 bladder carcinoma [15,16,17, 25, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

At the moment, some open questions remain. In fact, the maximum length cut-off of micrometric approach and/or the type of approaches have not been established yet. In order to correctly evaluate a TURB specimen, we suggest to perform serial sections in high-grade UC cases, when staging diagnosis is critical, keeping in mind all the clinical data including the position (dome, walls, trigone) of the resected bladder neoplasms. In order to avoid differences in substaging diagnosis, the type of approach to substage the pT1 tumor should be easy to perform. The micrometric approach with a small length cut-off may be useful to stratify, within the pT1 category, two groups of patients. Different length cut-off such as 0.5 mm for the trigone area, characterized by a thin LP, and 1 mm for the dome area, characterized by a thick LP, could be applied.

pT1 interobserver reproducibility

The reproducibility of pT1 substaging, particularly the micrometric approach, remains to be fully investigated. Using the 0.5 mm cut-off, the interobserver agreement between two pathologists was of 81% (58). Overall, interobserver variation in pT1 diagnosis is considerable, more in terms of downstaging (15%–56%) than upstaging (3%–13%) [19, 24, 68, 69]. Given the significant downstaging in pT1 cancer with its inherent prognostic ramification, substaging is beneficial in a way of separating tumors with unequivocal small foci of invasion staged as pT1 from frankly extensively invasive pT1, which may be almost akin to pT2 tumors.

References

Bochner BH, Hansel DE, Efstathiou JA et al (2016) Urinary bladder. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL et al (eds) AJCC cancer staging manual, 8th edn. Springer, Chicago, pp 757–765

Moch H, Humphrey PA, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE (2016) WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs, 4th edn. WHO Press, Geneva

Bostwick DG, Ramnani DM, Cheng L (1999) Diagnosis and grading of bladder cancer and associate lesions. Urol Clin Nth Am 26:493–507

Epstein JI, Amin MB, Reuter VR, Mostofi FK (1998) The World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder. Bladder Consensus Conference Committee. Am J Surg Pathol 22:1435–1448. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199812000-00001

Jimenez RE, Keany TE, Hardy HT, Amin MB (2000) pT1 Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: criteria for diagnosis, pitfalls, and clinical implications. Adv Anat Pathol 7:13–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/00125480-200007010-00004

Toll AD, Epstein JI (2012) Invasive low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 41 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 36:1081–1086. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e318253d6e0

Sylvester RJ, Van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, Witjes JA, Bouffioux C, Denis L et al (2006) Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage TaT1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol 49:466–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031

Emiliozzi P, Pansadoro A, Pansadoro V (2008) The optimal management of T1G3 bladder cancer. BJU Int 102:1265–1273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07969.x

Esrig D, Freeman JA, Stein JP, Skinner DG (1997) Early cystectomy for clinical stage T1 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Semin Urol Oncol 15:154–160

Kulkarni GS, Hakenberg OW, Gschwend JE, Thalmann G, Kassouf W, Kamat A, Zlotta A (2010) An updated critical analysis of the treatment strategy for newly diagnosed high-grade T1 (previously T1G3) bladder cancer. Eur Urol 57:60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2009.08.024

Martin-Doyle W, Leow JJ, Orsola A, Chang SL, Bellmunt J (2015) Improving selection criteria for early cystectomy in high-grade t1 bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of 15,215 patients. J Clin Oncol 33:643–650. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.57.6967

Babjuk M, Böhle A, Burger M, Capoun O, Cohen D, Compérat EM, Hernández V, Kaasinen E, Palou J, Rouprêt M, van Rhijn B, Shariat SF, Soukup V, Sylvester RJ, Zigeuner R (2017) EAU guidelines on non–muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2016. Eur Urol 71:447–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.041

Pan CC (2013) Does muscolaris mucosae invasion in extensively lamina propria-invasive high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma provide additional prognostic information? Am J Surg Pathol 37:459–460. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182796e72

Soukup V, Duskova J, Pesl M, Capoun O, Feherova Z, Zámečník L et al (2014) The prognostic value of T1 bladder cancer substaging: a single institution retrospective study. Urol Int 92:150–156. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355358

Brimo F, Wu C, Zeizafour N, Tanguay S, Aprikian A, Mansure JJ, Kassouf W (2013) Prognostic factors in T1 bladder urothelial carcinoma: the value of recording milimetric depth of invasion, diameter of invasive carcinoma, and muscolaris propria invasion. Hum Pathol 44:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2012.04.020

Hu Z, Mudaliar K, Quek ML, Paner GP, Barkan GA (2014) Measuring the dimension of invasive component in pT1 urothelial carcinoma in transurethral resection specimens can predict time to recurrence. Ann Diagn Pathol 18:49–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2013.11.002

van Rhijn BW, van der Kwast TH, Alkhateeb SS, Fleshner NE, van Leenders GJ, Bostrom PJ, van der Aa M, Kakiashvili DM, Bangma CH, Jewett MA, Zlotta AR (2012) A new and highly prognostic system to discern T1 bladder cancer substage. Eur Urol 61:378–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2011.10.026

Bayraktar Z, Gurbuz G, Taşci AI, Sevin G (2001) Staging error in the bladder tumor: the correlation between stage of TUR and cystectomy. Int Urol Nephrol 33:627–629. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020553812554

Bol MG, Baak JP, Buhr-Wildhagen S, Kruse AJ, Kjellevold KH, Janssen EA, Mestad O, Øgreid P (2003) Reproducibility and prognostic variability of grade and lamina propria invasion in stages Ta, T1 urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol 169:1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000055471.78783.ae

Cheng L, Neumann RM, Weaver AL, Cheville JC, Leibovich BC, Ramnani DM, Scherer BG, Nehra A, Zincke H, Bostwick DG (2000) Grading and staging of bladder carcinoma in transurethral resection specimens. Correlation with 105 matched cystectomy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol 113:275–279. https://doi.org/10.1309/94B6-8VFB-MN9J-1NF5

Compérat E, Egevad L, Lopez-Beltran A, Camparo P, Algaba F, Amin M, Epstein JI, Hamberg H, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa C, Kristiansen G, Montironi R, Pan CC, Heloir F, Treurniet K, Sykes J, van der Kwast T (2013) An interobserver reproducibility study on invasiveness of bladder cancer using virtual microscopy and heatmaps. Histopathology 63:756–766. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.12214

Miladi M, Peyromaure M, Zerbib M, Saïghi D, Debré B (2003) The value of a second transurethral resection in evaluating patients with bladder tumours. Eur Urol 43:241–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00040-x

Tosoni I, Wagner U, Sauter G, Egloff M, Knönagel H, Alund G, Bannwart F, Mihatsch MJ, Gasser TC, Maurer R (2000) Clinical significance of interobserver differences in the staging and grading of superficial bladder cancer. BJU Int 85:48–53. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00356.x

Van Der Meijden A, Sylvester R, Collette L, Bono A, Ten Kate F (2000) The role and impact of pathology review on stage and grade assessment of stages Ta and T1 bladder tumors: a combined analysis of 5 European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer trials. J Urol 164:1533–1537. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005392-200011000-00017

Cheng L, Neumann RM, Weaver AL, Spotts BE, Bostwick DG (1999) Predicting cancer progression in patients with stage T1 bladder carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 17:3182–3187. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3182

Vakar-Lopez F, Shen SS, Zhang S, Tamboli P, Ayala AG, Ro JY (2007) Muscularis mucosae of the urinary bladder revisited with emphasis on its hyperplastic patterns: a study of a large series of cystectomy specimens. Ann Diagn Pathol 11:395–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.12.014

Bostwick DG, Lopez-Beltran A (1999) Bladder biopsy interpretation. UPP, Washington DC

Amin MB, Trpkov K, Lopez-Beltran A, Grignon D; Members of the ISUP Immunohistochemistry in Diagnostic Urologic Pathology Group (2014) Best practices recommendations in the application of immunohistochemistry in the bladder lesions: report from the International Society of Urologic Pathology consensus conference. Am J Surg Pathol 38:e20–e34. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000240

Bovio IM, Al-Quran SZ, Rosser CJ, Algood CB, Drew PA, Allan RW (2010) Smoothelin immunohistochemistry is a useful adjunct for assessing muscularis propria invasion in bladder carcinoma. Histopathology 56:951–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03575.x

Chakravarthy R, Ahmed K, Abbasi S, Cotterill A, Parveen N (2011) In response--a modified staining protocol for Smoothelin immunostaining. Virchows Arch 459:119–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-011-1093-y

Council L, Hameed O (2009) Differential expression of immunohistochemical markers in bladder smooth muscle and myofibroblasts, and the potential utility of desmin, smoothelin, and vimentin in staging of bladder carcinoma. Mod Pathol 22:639–650. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.9

Miyamoto H, Sharma RB, Illei PB, Epstein JI (2010) Pitfalls in the use of smoothelin to identify muscularis propria invasion by urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 34:418–422. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ce5066

Paner GP, Brown JG, Lapetino S, Nese N, Gupta R, Shen SS, Hansel DE, Amin MB (2010) Diagnostic use of antibody to smoothelin in the recognition of muscularis propria in transurethral resection of urinary bladder tumor (TURBT) specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 34:792–799. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181da7650

Paner GP, Shen SS, Lapetino S, Venkataraman G, Barkan GA, Quek ML, Ro JY, Amin MB (2009) Diagnostic utility of antibody to smoothelin in the distinction of muscularis propria from muscularis mucosae of the urinary bladder: a potential ancillary tool in the pathologic staging of invasive urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 33:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181804727

Lindh C, Nilsson R, Lindstrom ML, Lundin L, Elmberger G (2011) Detection of smoothelin expression in the urinary bladder is strongly dependent on pretreatment conditions: a critical analysis with possible consequences for cancer staging. Virchows Arch 458:665–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-011-1076-z

Paner GP, Montironi R, Amin MB (2017) Challenges in pathologic staging of bladder cancer: proposals for fresh approaches of assessing pathologic stage in light of recent studies and observations pertaining to bladder histoanatomic variances. Adv Anat Pathol 24:113–127. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAP.0000000000000152

Paner GP, Ro JY, Wojcik EM, Venkataraman G, Datta MW, Amin MB (2007) Further characterization of the muscle layers and lamina propria of the urinary bladder by systematic histologic mapping: implications for pathologic staging of invasive urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 31:1420–1429. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180588283

Lopez-Beltran A, Luque RJ, Mazzucchelli R, Scarpelli M, Montironi R (2002) Changes produced in the urothelium by traditional and newer therapeutic procedures for bladder cancer. J Clin Pathol 55:641–647. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.55.9.641

Lopez-Beltran A, Paner G, Montironi R, Raspollini MR, Cheng L (2017) Iatrogenic changes in the urinary tract. Histopathology 70:10–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13090

Lopez-Beltran A, Henriques V, Montironi R, Cimadamore A, Raspollini MR, Cheng L (2019) Variants and new entities of bladder cancer. Histopathology 74:77–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13752

Lopez-Beltran A, Algaba F, Berney DM, Boccon-Gibod L, Camparo P, Griffiths D, Mikuz G, Montironi R, Varma M, Egevad L (2011) Handling and reporting of transurethral resection specimens of the bladder in Europe: a web-based survey by the European Network of Uropathology (ENUP). Histopathology 58:579–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03784.x

Amin MB, McKenney JK, Paner GP, Hansel DE, Grignon DJ, Montironi R, Lin O, Jorda M, Jenkins LC, Soloway M, Epstein JI, Reuter VE, International Consultation on Urologic Disease-European Association of Urology Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012 (2013) ICUD-EAU international consultation on bladder cancer 2012: pathology. Eur Urol 63:16–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.09.063

Comperat E, Varinot J (2016) Immunochemical and molecular assessment of urothelial neoplasms and aspects of the 2016 World Health Organization classification. Histopathology 69:717–726. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13025

Dixon JS, Gosling A (1983) Histology and fine structure of the muscolaris mucosae of the human bladder. J Anat 136:265–271

Younes M, Sussman J, True LD (1990) The usefulness of the level of the muscularis mucosae in the staging of invasive transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Cancer 66:543–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3<543::aid-cncr2820660323>3.0.co;2-r

Hasui Y, Osada Y, Kitada S, Nishi S (1994) Significance of invasion to the muscularis mucosae on the progression of superficial bladder cancer. Urology 43:782–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-4295(94)90134-1

Angulo JC, Lopez JI, Grignon DJ, Sanchez-Chapado M (1995) Muscularis mucosa differentiates two populations with different prognosis in stage T1 bladder cancer. Urology 45:47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-4295(95)96490-8

Bernardini S, Billerey C, Martin M, Adessi GL, Wallerand H, Bittard H (2001) The predictive value of muscularis mucosae invasion and p53 over expression on progression of stage T1 bladder carcinoma. J Urol 165:42–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005392-200101000-00011

Hermann GG, Horn T, Steven K (1998) The influence of the level of lamina propria invasion and the prevalence of p53 nuclear accumulation on survival in stage T1 transitional cell bladder cancer. J Urol 159:91–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64021-7

Holmäng S, Hedelin H, Anderström C, Holmberg E, Johansson SL (1997) The importance of the depth of invasion in stage T1 bladder carcinoma: a prospective cohort study. J Urol 157:800–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65044-4

Kondylis FI, Demirci S, Ladaga L, Kolm P, Schellhammer PF (2000) Outcomes after intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin are not affected by substaging of high grade T1 transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol 163:1120–1123

Lee JY, Joo HJ, Cho DS, Kim SI, Ahn HS, Kim SJ (2012) Prognostic significance of substaging according to the depth of lamina propria invasion in primary T1 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Kor J Urol 53:317–323. https://doi.org/10.4111/kju.2012.53.5.317

Orsola A, Trias I, Raventós CX, Español I, Cecchini L, Búcar S, Salinas D, Orsola I (2005) Initial high-grade T1 urothelial cell carcinoma: feasibility and prognostic significance of lamina propria invasion microstaging (T1a/b/c) in BCG-treated and BCG-non-treated patients. Eur Urol 48:231–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2005.04.013

Smits G, Schaafsma E, Kiemeney L, Caris C, Debruyne F, Witjes JA (1998) Microstaging of pT1 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: identification of subgroups with distinct risks of progression. Urology 52:1009–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00374-4

Farrow GM, Utz DC (1982) Observations on microinvasive transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Clin Oncol 1:609–615

Amin MB, Gomez JA, Young RH (1997) Urothelial transitional cell carcinoma with endophytic growth patterns: a discussion of patterns of invasion and problems associated with assessment of invasion in 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 21:1057–1068. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199709000-00010

Lopez-Beltran A, Cheng L, Andersson L, Brausi M, de Matteis A, Montironi R, Sesterhenn I, van det Kwast KT, Mazerolles C (2002) Preneoplastic non-papillary lesions and conditions of the urinary bladder: an update based on the Ancona International Consultation. Virchows Arch 440:3–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-001-0577-6

van der Aa MN, van Leenders GJ, Steyerberg EW, van Rhijn BW, Jöbsis AC, Zwarthoff EC, van der Kwast TH (2005) A new system for substaging pT1 papillary bladder cancer: a prognostic evaluation. Hum Pathol 36:981–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2005.06.017

Bertz S, Denzinger S, Otto W, Wieland WF, Stoehr R, Hofstaedter F, Hartmann A (2011) Substaging by estimating the size of invasive tumour can improve risk stratification in pT1 urothelial bladder cancer-evaluation of a large hospital-based single-centre series. Histopathology 59:722–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03989.x

Chang WC, Chang YH, Pan CC (2012) Prognostic significance in substaging of T1 urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma on transurethral resection. Am J Surg Pathol 36:454–461. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31823dafd3

van Rhijn BW, Liu L, Vis AN, Bostrom PJ, Zuiverloon TC, Fleshner NE, van der Aa M, Alkhateeb SS, Bangma CH, Jewett MA, Zwarthoff EC, Bapat B, van der Kwast T, Zlotta AR (2012) Prognostic value of molecular markers, sub-stage and European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer risk scores in primary T1 bladder cancer. BJU Int 110:1169–1176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.10996.x

Rouprêt M, Seisen T, Compérat E, Larré S, Mazerolles C, Gobet F et al (2013) Prognostic interest in discriminating muscularis mucosa invasion (T1a vs T1b) in nonmuscle invasive bladder carcinoma: French national multicenter study with central pathology review. J Urol 189:2069–2076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.120

Olsson H, Hultman P, Rosell J, Jahnson S (2013) Population-based study on prognostic factors for recurrence and progression in primary stage T1 bladder tumours. Scand J Urol 47:188–195. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365599.2012.719539

De Marco V, Cerruto MA, D'Elia C, Brunelli M, Otte O, Minja A et al (2014) Prognostic role of substaging in T1G3 transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Mol Clin Oncol 22:575–580. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2014.290

Patriarca C, Hurle R, Moschini M, Freschi M, Colombo P, Colecchia M, Ferrari L, Guazzoni G, Conti A, Conti G, Lucianò R, Magnani T, Colombo R (2016) Usefulness of pT1 substaging in papillary urothelial bladder carcinoma. Diagn Pathol 11:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-016-0466-6

Lawless M, Gulati R, Tretiakova M (2017) Stalk versus base invasion in pT1 papillary cancers of the bladder: improved substaging system predicting the risk of progression. Histopathology 71:406–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13247

Leivo MZ, Sahoo D, Hamilton Z, Mirsadraei L, Shabaik A, Parsons JK, Kader AK, Derweesh I, Kane C, Hansel DE (2018) Analysis of T1 bladder cancer on biopsy and transurethral resection specimens: comparison and ranking of T1 quantification approaches to predict progression to muscularis propria invasion. Am J Surg Pathol 42:e1–e10. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000964

Giunchi F, Panzacchi R, Capizzi E, Schiavina R, Brunocilla E, Martorana G, D'Errico A, Fiorentino M (2016) Role of inter-observer variability and quantification of muscularis propria in the pathological staging of bladder cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 14:e307–e312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clgc.2016.01.002

van Rhijn BW, van der Kwast TH, Kakiashvili DM, Fleshner NE, van der Aa MN, Alkhateeb S, Bangma CH, Jewett MA, Zlotta AR (2010) Pathological stage review is indicated in primary pT1 bladder cancer. BJU Int 106:206–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09100.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Raspollini contributed to the writing of manuscript. Dr. Mazzucchelli contributed to the production of the figures. Prof Montironi, Dr. Cimadamore, Prof Cheng, and Prof Lopez-Beltran critically revised the work. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Quality in Pathology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raspollini, M.R., Montironi, R., Mazzucchelli, R. et al. pT1 high-grade bladder cancer: histologic criteria, pitfalls in the assessment of invasion, and substaging. Virchows Arch 477, 3–16 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-020-02808-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-020-02808-6