Abstract

Renal cell tumors with mixed morphology resembling multiple renal cell carcinoma (RCC) subtypes are generally regarded as unclassified RCC. However, occasionally, papillary adenoma or RCC appears admixed with a larger, different tumor histology. We retrieved 17 renal tumors containing a papillary adenoma or papillary RCC component admixed with another tumor histology and studied them with immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Larger tumors were oncocytomas (n = 10), chromophobe RCCs (n = 5), borderline oncocytic tumor (n = 1), and clear cell RCC (n = 1). The size of papillary component ranged from 1 to 34 mm. One tumor was an oncocytoma encircled by a cyst (2.0 cm) with papillary hyperplasia of the lining. The papillary lesions were diffusely cytokeratin 7 positive (17/17), in contrast to “host” tumors. Alpha-methylacyl-coA-racemase labeling was usually stronger in the papillary lesions (13/15). KIT was negative in all papillary lesions and the clear cell RCC and positive in 16/16 oncocytic or chromophobe tumors. Eight of 15 (53%) collision tumors had differing FISH results in the two components. A papillary renal cell proliferation within another tumor is an uncommon phenomenon with predilection for oncocytoma and chromophobe RCC, possibly related to their common entrapment of benign tubules. When supported by distinct morphology and immunohistochemistry in these two components, this phenomenon should be diagnosed as a collision of two processes. A diagnosis of unclassified RCC should be avoided, due to potential misrepresentation as an aggressive renal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of recognized renal cell tumors has dramatically grown with evolving classification schemes to currently include 16 defined entities and four emerging or provisional entities in the latest World Health Organization (WHO) Classification [1,2,3]. However, occasional tumors still defy classification, often due to overlapping or mixed features of multiple tumor types histologically and immunohistochemically, warranting diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma, unclassified [4]. A current exception to this is a hybrid renal cell tumor that combines two distinct phenotypic and immunohistochemical components of oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (so-called hybrid oncocytoma-chromophobe tumor and similar terminology), which is currently incompletely understood but provisionally considered a low-grade carcinoma with a favorable behavior [3,4,5]. Other combinations of more than one recognized renal cell tumor entity fall in the definition of unclassified renal cell carcinoma according to the current classification. A common perception in clinical practice is that renal cell carcinoma unclassified is an aggressive tumor type [6, 7]. However, we have encountered occasional tumors that have a papillary component intermingled within another tumor type, raising a differential diagnosis that includes collision tumor (sometimes between two benign lesions) and unclassified renal cell carcinoma with a mixed histologic pattern. In this study, we examine 17 tumors with a papillary component admixed with another histology.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions. Tumors from the institutional and consultation files of the authors were retrieved based on reported diagnoses or descriptions of a papillary component within or associated with another renal cell tumor type. Cases were included in the study only if the two components were at least focally intermingled, in contrast to adjacent but separate papillary adenomas. Histopathology was reviewed for tumor sizes and histologic features of the two components, with special attention to newly defined features distinguishing papillary adenoma from papillary renal cell carcinoma (presence of tumor pseudocapsule, size threshold of 1.5 cm, and WHO/International Society of Urological Pathology nucleolar grade 3) in the 2016 WHO Classification [8]. Two tumors were considered for the study but excluded, as described in the Supplemental Material.

Immunohistochemistry was performed in a Dako automated instrument, using antibodies against alpha-methylacyl-coA-racemase (AMACR/P504S (13H4; Dako Corp, Carpinteria, CA, USA), carbonic anhydrase IX (polyclonal rabbit; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, UK), CD10 (56C6; Dako Corp), cytokeratin 7 (OV-TL 12/30; Dako Corp), KIT (CD117, YR145; Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA), and vimentin (V9; Dako Corp). Positive and negative controls yielded appropriate results for each. In a subset of cases, the same antibody staining panel was performed at the originating institutions.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed for loss of chromosome 3p25 and gain (trisomy) of chromosome 7 or 17 in both morphologically different components of the tumor in the laboratory of one of the authors (LC) using methods previously described [9,10,11,12]. Briefly, multiple 4-μm sections were obtained from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks containing neoplastic tissue. A hematoxylin and eosin-stained slide from each block was examined to identify areas of neoplastic tissue for FISH analysis, which was marked for the papillary lesion and the other tumor component. The chromosomal probe directed against 3p25 (RP11-572 M14) was obtained from Empire Genomics (Empire Genomics, Buffalo, New York). Chromosome enumeration probes (CEPs) for chromosomes 3, 7, and 17 were obtained from Vysis (Abbott, Downers Grove, IL). Deletion of chromosome 3p was assessed using a probe cocktail containing BAC clone probe to chromosome 3p25 (RP11-572 M14, green) and CEP3 (orange). Chromosome 7 and 17 alterations were assessed using a probe cocktail containing probe CEP7 (green) and CEP17 (orange). For each slide, 100 to 150 nuclei from tumor tissue were scored for probe signals under the fluorescence microscope with × 1000 magnification. The cutoff value for 3p deletion was defined as a 3p25/CEP3 ratio of ≤ 0.7. Definitions of chromosomal trisomy for chromosomes 7 and 17 were based on the Gaussian model and were related to the non-neoplastic renal cortex control cell signals. The cutoff values were set for each probe at the mean plus and minus 3 standard deviations of the control values.

Results

The study included samples from five women and 12 men ranging in age from 47 to 80 years old (median, 66 years). Follow-up of greater than 1 year was available in eight patients and ranged from 14 to 79 months (median 56 months). All patients were alive with no evidence of recurrent or metastatic renal tumor. One patient had lymphadenopathy in the clinical setting of known lymphoma, which was confirmed by resection of lymph nodes at the time of nephrectomy to be involvement by lymphoma (the patient with a borderline oncocytic tumor).

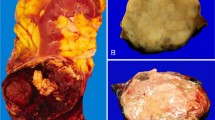

The main tumor was most commonly oncocytoma (10 tumors and 1 with borderline features of oncocytoma vs chromophobe renal cell carcinoma) (Fig. 1), including 2 oncocytomas with renal vein branch invasion (Fig. 2). Next most common was chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (5 cases). Only one main tumor was a clear cell renal cell carcinoma and was interpreted as a collision phenomenon based on the combined immunohistochemical and genetic findings (Fig. 3). The papillary component consisted of 12 papillary adenomas and 4 papillary renal cell carcinomas. One additional oncocytoma tumor was encircled by a cyst with papillary proliferation of the cyst lining, morphologically reminiscent of papillary hyperplasia of cysts encountered in polycystic kidney disease or so-called atypical cysts (Fig. 4) [13]. None of the papillary lesions was reclassified from renal cell carcinoma to adenoma after reassessment in light of the updated 2016 WHO criteria allowing papillary adenomas to be up to 1.5 cm, with no pseudocapsule and nucleolar grade 1–2 [8]. However, two papillary adenomas greater than 0.5 cm were diagnosed after 2016, and three lesions with sizes less than 1.5 cm remained interpreted as renal cell carcinomas due to encapsulation or nucleolar grade 3 (Table 1). Three tumors were originally diagnosed as unclassified renal cell carcinoma, due to mixed histologic features, all of which were reclassified as a collision of two lesions based on the data from this study. (Two tumors originally reported as variations of unclassified renal cell carcinoma were excluded and are discussed in the Supplemental Material.)

a A small focus of papillary renal cell carcinoma within an oncocytoma, with higher magnification (b) showing the papillary lesion (left) and oncocytoma (right). Immunohistochemical staining revealed the papillary lesion to be alpha-methylacyl-coA-racemase (c) and cytokeratin 7 (d) positive, with the opposite pattern in the oncocytoma. KIT (e, f) was strongly positive in the oncocytoma but labeled only scattered mast cells in the papillary lesion

a A small focus of papillary RCC (lower right) within a clear cell RCC. Higher magnification (b) shows the papillary lesion (upper left) and clear cell RCC (bottom right). Immunohistochemical staining revealed the clear cell RCC to be carbonic anhydrase IX positive (c), whereas the papillary lesion exhibited stronger labeling for alpha-methylacyl-coA-racemase (d), and diffuse labeling for cytokeratin 7 (e). Both tumors exhibited patchy labeling for CD10 (f) but slightly greater in the clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Abbreviation: RCC, renal cell carcinoma

All papillary lesions (17/17) were positive for cytokeratin 7 (Table 2), and almost all (13/15) had stronger labeling for AMACR than the main tumor. Papillary lesions were uniformly negative for KIT (17/17) compared to all oncocytic and chromophobe tumors, which were positive in a membranous pattern (16/16). Vimentin was usually positive in the papillary lesion (12/16) and negative in all oncocytic and chromophobe tumors (0/14). Carbonic anhydrase IX was performed only in cases that included a differential diagnosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma, and this labeled only the clear cell renal cell carcinoma component in the single included clear cell case (see also Supplemental Material).

Using FISH, trisomy of chromosome 7 or 17 was encountered in the papillary areas only from 8/15 cases tested (Table 3) and none of the corresponding main tumors. One chromophobe tumor had loss of chromosome 17 using these probes. Loss of chromosome 3p was not identified in the sole included clear cell renal cell carcinoma case.

Discussion

Collision tumors composed of papillary renal cell neoplasms and other renal tumor types, often oncocytoma, have been predominantly described in individual case reports [14,15,16], as noted by a recent literature review that revealed eight cases of oncocytoma and papillary renal cell carcinoma [17]. Notably, however, several of these papillary lesions measured less than 1.5 cm, which might qualify for classification as papillary adenomas in the updated WHO Classification, depending on grade and encapsulation [8]. Other unusual renal tumor combinations have also been described, including a recent report of oncocytoma with entrapped mucinous tubular and spindle cell carcinoma [18], which itself has many overlapping characteristics with papillary renal cell proliferations. Other reports have described development of papillary tumors within mixed epithelial and stromal tumors of the kidney [19, 20].

Most of the main tumors in this study were either oncocytomas or chromophobe renal cell carcinomas, which are potentially related lesions, sometimes believed to represent a spectrum of tumors with a similar cell of origin. Since these each account for only 5% or less of adult renal neoplasms, we hypothesize that this occurrence may be particularly enriched in oncocytic and chromophobe tumors, perhaps due to their tendency to be either unencapsulated or incompletely encapsulated [21, 22] with frequent entrapment of non-neoplastic tubules. In contrast, although clear cell renal cell carcinoma is overwhelmingly more common, these tumors are often surrounded by a more robust peritumoral fibromuscular pseudocapsule [21, 22], and lack entrapment of non-neoplastic renal tubules, which may account for the rarity of this phenomenon in clear cell renal cell carcinomas (only one example in the current study, with one case excluded). It is difficult to be certain whether the development of these papillary lesions within oncocytic tumors is somehow induced or encouraged by the growth of the main tumor, resulting from some interplay between the neoplasm and entrapped tubules, or whether this identified only fortuitously, since more sampling is directed at the tumor than kidney tissue away from the tumor, which might also harbor incidental papillary adenomas that could become entrapped if overgrown by another tumor.

Diagnostically, recognizing this scenario as two distinct entities forming a collision lesion may be of critical importance to patient management in some cases. The most common scenario (oncocytoma + papillary adenoma) represents the collision of two benign tumors; however, this could be interpreted as a single unclassified renal cell carcinoma if regarded as a single mass with mixed histologic patterns of multiple recognized entities. Although some pathologists may use modifiers such as “low-grade oncocytic,” or similar terms for oncocytic renal tumors that defy definite classification [5], there nonetheless remains the perception that any unclassified renal cell carcinoma is potentially aggressive [6, 7]. Indeed, three tumors from the main study cohort were originally reported as unclassified renal cell carcinomas for this reason, all of which could be reclassified as two distinct lesions for the purposes of the study. Additionally, two tumors were originally regarded as unclassified renal cell carcinomas and excluded, one being a clear cell renal cell carcinoma with morphologic heterogeneity and one being an oncocytoma with different morphology of the tubules in the central scar area (see Supplemental Material) [23]. The likelihood of considering a diagnosis of unclassified renal cell carcinoma may also depend on the size of the papillary lesion, probably being less likely for a minute papillary adenoma (which might be overlooked or disregarded), compared to a larger papillary neoplasm. Two oncocytomas in this series had renal vein branch extension, a feature that although worrisome in concept is increasingly accepted as compatible with a diagnosis of oncocytoma without altering the benign behavior of this tumor [4, 5, 23,24,25]. In this scenario, the differential diagnosis would also be between a collision of two benign neoplasms and a high-stage renal cell carcinoma (with renal vein branch invasion). These entrapped papillary lesions are now also more likely to meet criteria for an adenoma, in light of the recent WHO Classification changes, which allows a maximum size of 1.5 cm for papillary adenomas, compared to the previous 0.5 cm, as long as the tumor has low WHO/ISUP nucleolar grade and lacks encapsulation [8].

This occurrence may also have implications for the increasing practice of renal mass biopsy [26,27,28,29]. Non-diagnostic or discrepant renal mass biopsy diagnoses most often can be presumed to represent sampling error, in which the true neoplasm is inadequately captured or not captured at all. However, clinical literature does include the phenomenon of “hybrid” histology among possible causes of diagnostic discrepancy, generally representing the phenomenon of hybrid oncocytoma-chromophobe renal cell carcinoma tumor [30, 31]. A problem of so-called hybrid tumors is that there is not a clear pathological definition. Some pathologists may use this term for any oncocytic neoplasm that exhibits atypical features, whereas others would reserve it for “mosaic” neoplasms, particularly in the context of a clinical syndrome [5]. Nonetheless, the occasional occurrence of papillary proliferations within oncocytic neoplasms, sometimes reaching criteria for papillary renal cell carcinoma, adds to the spectrum of tumor-in-tumor phenomena that may cause a diagnostic discrepancy in renal mass biopsy, albeit likely very rarely. Although the scenario described in this study could be considered a hybrid, due to collision of two different tumor types, we believe such terminology should be avoided, to prevent confusion with oncocytoma-chromophobe renal cell carcinoma tumors, where hybrid nomenclature is more typically used.

In most cases in this study, the immunohistochemical and molecular characteristics support distinction of the two components, with a few exceptions. Labeling for AMACR, vimentin, cytokeratin 7, and KIT (Table 4) was typically strikingly different between papillary neoplasms and oncocytic or chromophobe tumors (with cytokeratin 7, vimentin, and AMACR stronger and uniformly positive in the former). Although chromophobe renal cell carcinoma is generally considered to be cytokeratin 7-positive, positivity in the 5 chromophobe tumors in this series ranged from negative to patchy, a phenomenon we have encountered in some cases, especially the eosinophilic variant of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma [23]. One tumor, composed of papillary proliferation of a cyst surrounding an oncocytoma, likely represents a different phenomenon than classic papillary adenoma, perhaps more akin to papillary hyperplasia of cysts in polycystic kidney disease or proliferation of cysts in other contexts [13], as this papillary lesion was negative for AMACR. The presence of trisomy of chromosomes 7 and 17, although found in over half of cases, was not present uniformly in the papillary lesions, perhaps influenced by several factors, including difficulty evaluating sufficient numbers of neoplastic cells in small papillary adenomas with FISH and possibly a lower rate of this alteration in early adenomas compared to larger fully developed renal cell carcinomas. Additionally, although trisomy 7 and 17 are best established in type 1 papillary tumors [32], it is now increasingly recognized that papillary renal cell carcinoma can be a molecularly heterogeneous category with non-type 1 tumors often lacking these alterations or having entirely different copy number patterns [33].

Since conclusion of the study patient accrual, one of us (ONK) has encountered two more patients with a similar scenario. One patient was a 65-year-old woman who had three simultaneous unilateral partial nephrectomies performed for peripheral lesions. All tumors were oncocytomas and measured 4.5 cm, 1.5 cm, and 1.2 cm in largest dimensions, and all of them demonstrated entrapped papillary proliferations. All three main tumors were negative for cytokeratin 7 and papillary proliferations were positive. Another patient was a 59-year-old woman who had a partial nephrectomy performed for 6.6 cm WHO/ISUP grade 3 clear cell renal cell carcinoma. This carcinoma had an area of regression with only sinusoidal vasculature without residual tumor cells [34]. In this area of regression adjacent to the peritumoral fibromuscular pseudocapsule, there was a 0.2-cm papillary adenoma.

A potential weakness of the study is a relatively short follow-up. Generally, recurrence or systemic spread would not be expected over this time period in low-stage renal cell carcinomas. However, as we argue that the admixture of papillary component with another tumor type should not be classified as unclassified renal cell carcinoma, the short follow-up time is of some limited value, as there was no aggressive behavior.

In summary, identification of a cytologically and immunohistochemically distinct papillary renal cell proliferation within another tumor is an uncommon phenomenon that appears to be strikingly overrepresented in oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. One possible explanation for this may be the lack or less robust tumor pseudocapsules in these entities and their common entrapment of non-neoplastic tubules. When encountering a renal tumor that has mixed morphology of a papillary neoplasm and another histology, we recommend that pathologists carefully evaluate the morphologic and immunohistochemical features (especially cytokeratin 7, AMACR, KIT, and vimentin for oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma), which can often support a diagnosis of a collision phenomenon. We suggest that rather than classifying cases with entrapped papillary proliferation as unclassified renal cell tumors, to report the host tumor and entrapped papillary lesion separately. However, this should be approached with caution in clear cell renal cell carcinoma, as it is considerably rarer and may represent morphologic heterogeneity within a higher-grade tumor in this context.

References

Moch H, Amin MB, Argani P et al. Renal cell tumours. In: Moch H, Humphrey PA, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016:14–17. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours; vol 8

Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM (2016) The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-part a: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol 70(1):93–105

Kryvenko ON, Epstein JI (2017) Latest novelties on the World Health Organization morphological classifications of genitourinary cancers. Eur Urol Suppl 16(12):199–209

Kryvenko ON, Jorda M, Argani P, Epstein JI (2014) Diagnostic approach to eosinophilic renal neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med 138(11):1531–1541

Williamson SR, Gadde R, Trpkov K, Hirsch MS, Srigley JR, Reuter VE, Cheng L, Kunju LP, Barod R, Rogers CG, Delahunt B, Hes O, Eble JN, Zhou M, McKenney JK, Martignoni G, Fleming S, Grignon DJ, Moch H, Gupta NS (2017) Diagnostic criteria for oncocytic renal neoplasms: a survey of urologic pathologists. Hum Pathol 63:149–156

Zisman A, Chao DH, Pantuck AJ, Kim HJ, Wieder JA, Figlin RA, Said JW, Belldegrun AS (2002) Unclassified renal cell carcinoma: clinical features and prognostic impact of a new histological subtype. J Urol 168(3):950–955

Karakiewicz PI, Hutterer GC, Trinh QD, Pantuck AJ, Klatte T, Lam JS, Guille F, de la Taille A, Novara G, Tostain J, Cindolo L, Ficarra V, Schips L, Zigeuner R, Mulders PF, Chautard D, Lechevallier E, Valeri A, Descotes JL, Lang H, Soulie M, Ferriere JM, Pfister C, Mejean A, Belldegrun AS, Patard JJ (2007) Unclassified renal cell carcinoma: an analysis of 85 cases. BJU Int 100(4):802–808

Eble JN, Moch H, Amin MB et al. Papillary adenoma. In: Moch H, Humphrey PA, Ulbright T.M., Reuter VE, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016:42–43. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours; vol 8

Williamson SR, Gupta NS, Eble JN, Rogers CG, Michalowski S, Zhang S, Wang M, Grignon DJ, Cheng L (2015) Clear cell renal cell carcinoma with borderline features of clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma: combined morphologic, immunohistochemical, and cytogenetic analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 39(11):1502–1510

Cheng L, MacLennan GT, Zhang S et al (2008) Evidence for polyclonal origin of multifocal clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 14:8087–8093

Gobbo S, Eble JN, Maclennan GT et al (2008) Renal cell carcinomas with papillary architecture and clear cell components: the utility of immunohistochemical and cytogenetical analyses in differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 32(12):1780–1786

Jones TD, Eble JN, Wang M et al (2005) Molecular genetic evidence for the independent origin of multifocal papillary tumors in patients with papillary renal cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 11:7226–7233

Matoso A, Chen YB, Rao V, Wang L, Cheng L, Epstein JI (2016) Atypical renal cysts: a morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol 40(2):202–211

Goyal R, Parwani AV, Gellert L, Hameed O, Giannico GA (2015) A collision tumor of papillary renal cell carcinoma and oncocytoma: case report and literature review. Am J Clin Pathol 144(5):811–816

Kominsky HD, Parker DC, Gohil D, Musial R, Edwards K, Kutikov A (2015) Some renal masses did not “read the book”: a case of a high grade hybrid renal tumor masquerading as a renal cyst on non-contrast imaging. Urol Case Rep 3(6):219–220

Ozer C, Goren MR, Egilmez T, Bal N (2014) Papillary renal cell carcinoma within a renal oncocytoma: case report of very rare coexistence. Can Urol Assoc J 8(11–12):E928–E930

McCroskey Z, Sim SJ, Selzman AA, Ayala AG, Ro JY (2017) Primary collision tumors of the kidney composed of oncocytoma and papillary renal cell carcinoma: a review. Ann Diagn Pathol 29:32–36

Arora K, Miller R, Mullick S, Shen S, Ayala AG, Ro JY (2018) Renal collision tumor composed of oncocytoma and mucinous tubular and spindle cell carcinoma: case report of an unprecedented entity. Hum Pathol 71:60–64

Hes O, Kujal P, Sach J, Nencka P, Michal M (2014) Adult biphasic renal tumors. Int J Surg Pathol 22(5):478–479

Mudaliar KM, Mehta V, Gupta GN, Picken MM (2014) Expanding the morphologic spectrum of adult biphasic renal tumors--mixed epithelial and stromal tumor of the kidney with focal papillary renal cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol 22(3):266–271

Jacob JM, Williamson SR, Gondim DD, Leese JA, Terry C, Grignon DJ, Boris RS (2015) Characteristics of the peritumoral pseudocapsule vary predictably with histologic subtype of T1 renal neoplasms. Urology. 86(5):956–961

Roquero L, Kryvenko ON, Gupta NS, Lee MW (2015) Characterization of fibromuscular pseudocapsule in renal cell carcinoma. Int J Surg Pathol 23(5):359–363

Wobker SE, Williamson SR (2017) Modern pathologic diagnosis of renal oncocytoma. J Kidney Cancer VHL 4(4):1–12

Wobker SE, Przybycin CG, Sircar K, Epstein JI (2016) Renal oncocytoma with vascular invasion: a series of 22 cases. Hum Pathol 58:1–6

Hes O, Michal M, Sima R et al (2008) Renal oncocytoma with and without intravascular extension into the branches of renal vein have the same morphological, immunohistochemical, and genetic features. Virchows Arch 452(2):193–200

Delahunt B, Samaratunga H, Martignoni G, Srigley JR, Evans AJ, Brunelli M (2014) Percutaneous renal tumour biopsy. Histopathology. 65(3):295–308

Evans AJ, Delahunt B, Srigley JR (2015) Issues and challenges associated with classifying neoplasms in percutaneous needle biopsies of incidentally found small renal masses. Semin Diagn Pathol 32(2):184–195

Halverson SJ, Kunju LP, Bhalla R, Gadzinski AJ, Alderman M, Miller DC, Montgomery JS, Weizer AZ, Wu A, Hafez KS, Wolf JS (2013) Accuracy of determining small renal mass management with risk stratified biopsies: confirmation by final pathology. J Urol 189(2):441–446

Tsivian M, Rampersaud EN Jr, del Pilar Laguna Pes M et al (2014) Small renal mass biopsy--how, what and when: report from an international consensus panel. BJU Int 113(6):854–863

Tomaszewski JJ, Uzzo RG, Smaldone MC (2014) Heterogeneity and renal mass biopsy: a review of its role and reliability. Cancer Biol Med 11(3):162–172

Ginzburg S, Uzzo R, Al-Saleem T et al (2014) Coexisting hybrid malignancy in a solitary sporadic solid benign renal mass: implications for treating patients following renal biopsy. J Urol 191(2):296–300

Pitra T, Pivovarcikova K, Alaghehbandan R, Hes O (2019) Chromosomal numerical aberration pattern in papillary renal cell carcinoma: review article. Ann Diagn Pathol 40:189–199

Michalova K, Steiner P, Alaghehbandan R et al (2018) Papillary renal cell carcinoma with cytologic and molecular genetic features overlapping with renal oncocytoma: analysis of 10 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol 35:1–6

Kryvenko ON, Roquero L, Gupta NS, Lee MW, Epstein JI (2013) Low-grade clear cell renal cell carcinoma mimicking hemangioma of the kidney: a series of 4 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 137(2):251–254

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SRW and ONK conceived and designed the study, researched and analyzed the data, and wrote, edited, and reviewed the manuscript. LC, RG, GAG, MJW, PJTS, NSG, DJG, and MJ researched and analyzed the data and edited and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors gave final approval for publication. SRW takes full responsibility for the work as a whole, including the study design, access to data, and the decision to submit and publish the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions. The need for written informed consent was waived.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 1024 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williamson, S.R., Cheng, L., Gadde, R. et al. Renal cell tumors with an entrapped papillary component: a collision with predilection for oncocytic tumors. Virchows Arch 476, 399–407 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-019-02648-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-019-02648-z