Abstract

Aim

Retrorectal tumors are rare and heterogeneous. They are often asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms, making management challenging. This study examines the diagnosis and treatment of retrorectal tumors.

Methods

Between 2002 and 2022, 21 patients with retrorectal tumors were treated in our department. We analyzed patient characteristics, diagnosis and treatment modalities retrospectively. Additionally, a literature review (2002–2023, “retrorectal tumors” and “presacral tumors”, 20 or more cases included) was performed.

Results

Of the 21 patients (median age 54 years, 62% female), 17 patients (81%) suffered from benign lesions and 4 (19%) from malignant lesions. Symptoms were mostly nonspecific, with pain being the most common (11/21 (52%)). Diagnosis was incidental in eight cases. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed in 20 (95%) and biopsy was obtained in 10 (48%). Twenty patients underwent surgery, mostly via a posterior approach (14/20 (70%)). At a mean follow-up of 42 months (median 10 months, range 1–166 months), the local recurrence rate was 19%. There was no mortality. Our Pubmed search identified 39 publications.

Conclusion

Our data confirms the significant heterogeneity of retrorectal tumors, which poses a challenge to management, especially considering the often nonspecific symptoms. Regarding diagnosis and treatment, our data highlights the importance of MRI and surgical resection. In particular a malignancy rate of almost 20% warrants a surgical resection in case of the findings of a retrorectal tumour. A local recurrence rate of 19% supports the need for follow up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Retrorectal tumors are rare and heterogeneous, with an estimated incidence of one in every 40,000 hospital admissions [1,2,3].

The retrorectal space is confined by the rectum with its mesorectal fascia anteriorly, the parietal pelvic fascia posteriorly and the peritoneum cranially. The distal end of the retrorectal space is defined by the fusion of the presacral, parietal pelvic fascia and mesorectal fascia, which cover the levator ani muscle. The parietal fascia separates the retrorectal space from the presacral space. The iliac vessels and ureters are located laterally [2, 4, 5].

The histologic diversity of retrorectal tumors with benign or malignant lesions results from the embryologic development, during which endo-, meso-, and ectodermal tissues undergo modifications. Tumors can be related to any of these. Retrorectal tumors are commonly categorized as congenital, neurogenic, osseous, inflammatory and miscellaneous [6,7,8].

Most tumors remain asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms and are often diagnosed incidentally [3]. Occasionally, they present as a palpable mass on digital rectal examination. Clinical examination, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are considered the gold standard for preoperative evaluation [1, 9,10,11]. Determining the exact anatomical location is essential to the surgical approach. A biopsy can be considered, although its value remains controversial [8, 12]. Retrorectal tumors should be completely resected, even if they are asymptomatic.

Due to their rarity and diverse clinical presentations, diagnosing and treating retrorectal tumors remain challenging. We share our 20-year experience with 21 patients, comparing it with existing literature.

Patients and methods

In our retrospective study, we identified 21 patients treated for retrorectal tumor at the Surgical Department of the University hospital Erlangen between 2002 and 2022. Of these, 20 underwent surgery. We analyzed demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender), symptoms, diagnosis, treatment (i.e., surgical approach, resection of bone structure), postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo classification [13]), histopathology and local recurrence. Data were obtained retrospectively from the patient record.

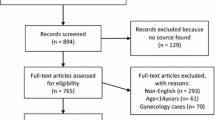

Furthermore, in a literature review (Fig. 1), we performed a Pubmed search on January 6, 2023 for abstracts from 2002 to 2023 with the terms “retrorectal tumors” (n = 360) and “presacral tumors” (n = 1058). Publications with fewer than 20 cases were excluded, as were reviews, manuscripts not available in english, pediatric cases and duplications in both search terms. The remaining publications (n = 39) were scrutinized and data extracted to tabulate the findings according to publication year, number of patients, gender, age, histopathology, rate of malignancy, surgical approach, postoperative morbidity, follow-up and local recurrence.

Results

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Thirteen were female (62%) and eight male (38%). The median age at operation (or, in the non-operated patient at first diagnosis) was 54 years (range 19–74 years). Thirteen patients (62%) presented with nonspecific symptoms: pain in the back, flank, pelvis, lower abdomen, anus or a feeling of anal pressure. One patient had right-sided weakened foot dorsiflexion. Eight patients (38%) were diagnosed incidentally during gynecologic examination, treatment of anal fistula, on MRI or CT for other reasons, and during a gynecologic operation.

MRI was performed in 20 (95%) patients (Fig. 2), CT scan in 9 (43%), endosonography in 7 (33%) and rectoscopy or colonoscopy in 17 (81%). Biopsies were obtained in 10 (48%).

Treatment

Twenty patients underwent surgery (Table 2); one patient with choroidal melanoma metastasis (diagnosis confirmed by biopsy) underwent radio- and immunotherapy.

A posterior approach (Kraske procedure) was used in 14 patients (70%) and an anterior approach in five (25%). A combined approach was required in one patient (5%). Resection of bone structures was necessary in nine (45%).

Postoperative complications occurred in seven patients (35%): three with wound healing disturbances and one each with a voiding dysfunction, a wound seroma, a hematoma and constipation. All seven patients reported pain. According to the Clavien-Dindo classification, category I occurred in four patients (20%), II in one (5%) and III in two (10%). Four patients had a local recurrence during a median follow-up of 10 months (range 1-166 months) and a mean follow up of 42 months. Reoperation was not required. There was no mortality observed.

Histopathologic findings

Histopathologic findings varied widely (Table 3). Seventeen patients (81%) had a benign lesion, the most common being a tailgut cyst in 10. In one patient it remained unclear whether the lesion was a tailgut or a duplication cyst. Schwannoma was diagnosed in three cases and an osseous pseudotumor, a lipoma and a teratoma in the other three.

Four tumors were revealed to be malignant (19%): a mucinous adenocarcinoma in a tailgut cyst, a choroidal melanoma metastasis, a solid fibrotic tumor (hemangiopericytoma) and an eosinophil chordoma.

Literature search

In the 39 publications, the recorded characterics regarding number of patients, gender, age, histopathology, rate of malignancy, surgical approach, postoperative morbidity, follow-up, and local recurrence are presented in Table 4.

Discussion

This study represents a single-institution series of retrorectal tumors and demonstrates a heterogeneity comparable to other reports and few systematic reviews [1,2,3,4, 9, 52, 53]. Its reported incidence ranges from 0.9 to 6.3 patients per year and is estimated as one in 40,000 hospital admissions [1, 3, 4, 52]. In our retrospective study, we report on 21 patients treated between 2002 and 2022.

Retrorectal tumors can be divided into five categories, congenital (55–65%) being the most common [1, 4, 6,7,8, 54]. As in our data the vast majority are benign and occur predominantly in females. Two of the four malignant tumors in our series, however, were found in male patients.

During embryologic development, a tail is formed from the endo-, meso-, and ectodermal tissues. If the tailgut does not recede, a remnant can result as a tailgut cyst [3, 6]. Resection is recommended because of the risk of malignant transformation [9, 55]. In our study, in accordance with published data [9, 55], benign tailgut cysts were the most common entity, while in one patient a poorly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma was found in the cyst. In another patient it remained unclear whether the lesion should be classified as a tailgut or duplication cyst.

The rate of malignancy is reported to range up to 26.6% [9, 56]. In 2022, Burke et al. described a malignancy rate of 17.3% in a large series of 144 tumors [16], which accords with our data. The highest rate of neoplasia of 26.6% was found in a systematic review comprising 196 patients [56].

The most frequent malignant retrorectal tumor is the chordoma, which results from persistence of endoderm, probably from residue of the chorda dorsalis [1, 8, 57]. In our study one patient presented with an eosinophilic chordoma.

With a frequency of 10-12%, neurogenic tumors are the second most common entity and are predominantly benign [4]. In various publications, schwannomas, in particular, have been described, as we found in our study (see Fig. 2) [1, 58].

Another 12–16% of retrorectal tumors are miscellaneous, often rare entities [3, 4, 7, 8]. In single patients, we found benign lesions (osseous pseudotumor, lipoma) as well as a malignant lesion with a solid fibrotic tumor (hemangiopericytoma), and a previously unreported metastasis of a choroidal melanoma.

The presentation can be nonspecific, even asymptomatic, and thus diagnosis is often incidental and at an advanced stage [1]. Indeed, the majority of our patients had nonspecific symptoms such as back and lower abdominal pain, and diagnosis was based on incidental findings in one quarter. Neurologic symptoms, such as the dorsiflexion of the foot seen in one, can also occur.

MRI and CT scans are considered the gold standard for evaluating these tumors beside the clinical examination. MRI can distinguish tissue properties and relations to neighboring organs [1, 6], often allowing accurate tumor diagnosis. In our series, 95.2% of the retrorectal tumors were confirmed or detected by MRI. CT allows clear visualization of bone structures and the differentiation between solid and cystic lesions [1, 6].

The use and value of biopsy remains controversial in current literature [1, 6, 12, 53]. Glasgow and Dietz refer to the risk of infection with subsequent sepsis, such as a biopsy of an anterior sacral meningocele leading to meningitis [8]. Additionally, the risk of biopsy-related tumor cell dissemination has to be considered. If tumor categorization is not possible and the option of neoadjuvant therapy must be considered, biopsy appears to be reasonable. In our study, in 47.6% of cases a biopsy was performed. It proved to be essential to therapeutic planning (radiation and immunotherapy) in the patient with the choroidal melanoma metastasis, our only patient not undergoing surgery.

Treatment depends on the tumor entity. In most cases - including asymptomatic tumors - a complete resection is indicated because of the potential for tumor growth with increasing symptoms and risk of malignant transformation [8, 52].

For surgical planning the location and size of the tumor and its relationship to neighbouring organs are relevant. Diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms have been proposed [11, 18, 32, 49]. Surgical options are posterior, anterior or combined approaches. As described by Dozois et al. [59, 60], a line through sacral vertebra three is helpful for decision-making. For small tumors below this line, the posterior approach may be sufficient, like that first described by Kraske in 1886 as the transcoccygeal approach for rectal cancer [8, 61]. This is the most common approach and was used In 70% of our patients. If the tumor is above the S3 line, the anterior, abdominal approach is advisable, although large tumors may require a combined approach. In 45% of our patients, a resection of bone structures (e.g. the os coccygis) became necessary to facilitate operative access or achieve complete tumor resection.

The postoperative complications in seven patients were Clavien-Dindo classification I in most (n = 4 (20%)) and were comparable to other studies [3, 13, 52]. In four patients a local recurrence was diagnosed. With no mortality, the resection of retrorectal tumors proved a predominantly safe procedure.

This study represents a comprehensive single-institution series of retrorectal tumors. The relatively small number of patients in this study likely may owe to the the rarity of retrorectal tumors. The retrospective design may affect accurate representation of the recurrence rate, however the represented rate of recurrence support the idea of a follow-up.

Conclusion

Retrorectal tumors are a heterogeneous entity. Our data show that most are benign. Resection is recommened and malignant entities may require multimodal therapy. In our cohort one patient had a very rare retrorectal metastasis of a choroidal melanoma, and another had a mucinous adenocarcinoma in a tailgut cyst. Biopsy may be helpful with inconclusive MRI findings and solid tumors. Decision-making by an interdisciplinary tumor board is recommended. The choice of surgical approach is determined by the tumor’s location and size. In our series, the posterior approach was most frequent.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, but are not public due to privacy restrictions, as they were obtained from medical records.

References

Neale JA (2011) Retrorectal tumors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg, 24:149 – 60. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1285999

Oguz A, Böyük A, Turkoglu A et al (2015) Retrorectal Tumors in adults: a 10-Year retrospective study. Int Surg 100:1177–1184. https://doi.org/10.9738/INTSURG-D-15-00068.1

Jao SW, Beart RW Jr, Spencer RJ, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM (1985) Retrorectal tumors. Mayo Clinic experience, 1960–1979. Dis Colon Rectum 28:644–652. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02553440

Strupas K, Poskus E, Ambrazevicius M (2011) Retrorectal tumours: literature review and vilnius university hospital santariskiu klinikos experience of 14 cases. Eur J Med Res 16:231–236. https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-783x-16-5-231

García-Armengol J, García-Botello S, Martinez-Soriano F, Roig JV, Lledó S (2008) Review of the anatomic concepts in relation to the retrorectal space and endopelvic fascia: Waldeyer’s fascia and the rectosacral fascia. Colorectal Dis 10:298–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01472.x

Messick CA (2018) Presacral (Retrorectal) tumors: optimizing the management strategy. Dis Colon Rectum 61:151–153. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001021

Uhlig BE, Johnson RL (1975) Presacral tumors and cysts in adults. Dis Colon Rectum 18:581–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02587141

Glasgow SC, Dietz DW (2006) Retrorectal tumors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 19:61–68. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-942346

Broccard SP, Colibaseanu DT, Behm KT et al (2022) Risk of malignancy and outcomes of surgically resected presacral tailgut cysts: a current review of the Mayo Clinic experience. Colorectal Dis 24:422–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.16030

Aflalo-Hazan V, Rousset P, Mourra N, Lewin M, Azizi L, Hoeffel C (2008) Tailgut cysts: MRI findings. Eur Radiol 18:2586–2593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-008-1028-4

Gong J, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Qiao L, Xu H, Zhu P, Yang B (2022) Primary malignant tumours and malignant transformation of cysts in the retrorectal space: MRI diagnosis and treatment outcomes. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 10:goac048. https://doi.org/10.1093/gastro/goac048

Merchea A, Larson DW, Hubner M, Wenger DE, Rose PS, Dozois EJ (2013) The value of preoperative biopsy in the management of solid presacral tumors. Dis Colon Rectum 56:756–760. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182788c77

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira et al (2009) The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 250:187–196. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2

Mualem W, Ghaith AK, Rush D et al (2022) Surgical management of sacral schwannomas: a 21-year mayo clinic experience and comparative literature analysis. J Neurooncol 159:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-022-03986-w

Zhao X, Zhou S, Liu N, Li P, Chen L (2022) Is there another posterior Approach for Presacral Tumors besides the Kraske Procedure? - a study on the feasibility and safety of Surgical Resection of primary presacral tumors via Transsacrococcygeal Transverse Incision. Front Oncol 12:892027. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.892027

Burke JR, Shetty K, Thomas O, Kowal M, Quyn A, Sagar P (2022) The management of retrorectal tumours: tertiary centre retrospective study. BJS Open 6:zrac044. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zrac044

Aubert M, Mege D, Parc Y et al (2021) Surgical Management of Retrorectal tumors: a French Multicentric experience of 270 consecutives cases. Ann Surg 274:766–772. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005119

Gould LE, Pring ET, Corr A et al (2021) Evolution of the management of retrorectal masses: a retrospective cohort study. Colorectal Dis 23:2988–2998. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15893

Zhang D, Sun Y, Lian L et al (2021) Long-term surgical outcomes after resection of presacral tumours and risk factors associated with recurrence. Colorectal Dis 23:2301–2310. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15691

Li Z, Lu M (2021) Presacral Tumor: insights from a Decade’s experience of this rare and diverse disease. Front Oncol 11:639028. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.639028

Carpelan-Holmström M, Koskenvuo L, Haapamäki C, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Lepistö A (2020) Clinical management of 52 consecutive retro-rectal tumours treated at a tertiary referral centre. Colorectal Dis 22:1279–1285. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15080

Yalav O, Topal U, Eray İC, Deveci MA, Gencel E, Rencuzogullari A (2020) Retrorectal tumor: a single-center 10-years’ experience. Ann Surg Treat Res 99:110–117. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2020.99.2.110

Houdek MT, Hevesi M, Griffin AM et al (2020) Can the ACS-NSQIP surgical risk calculator predict postoperative complications in patients undergoing sacral tumor resection for chordoma? J Surg Oncol 121:1036–1041. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.25865

Zhou J, Zhao B, Qiu H et al (2020) Laparoscopic resection of large retrorectal developmental cysts in adults: single-centre experiences of 20 cases. J Minim Access Surg 16:152–159. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmas.JMAS_214_18

Sakr A, Kim HS, Han YD et al (2019) Single-center experience of 24 cases of Tailgut Cyst. Ann Coloproctol 35:268–274. https://doi.org/10.3393/ac.2018.12.18

Poškus E, Račkauskas R, Danys D, Valančienė D, Poškus T, Strupas K (2019) Does a retrorectal tumour remain a challenge for surgeons? Acta Chir Belg 119:289–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015458.2018.1515397

Dziki Ł, Włodarczyk M, Sobolewska-Włodarczyk A et al (2019) Presacral tumors: diagnosis and treatment - a challenge for a surgeon. Arch Med Sci 15:722–729. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.61441

Dwarkasing RS, Verschuuren SI, van Leenders GJLH, Braun LMM, Krestin GP, Schouten WR (2017) Primary cystic lesions of the Retrorectal Space: MRI evaluation and clinical Assessment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 209:790–796. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.16.17329

Maddah G, Abdollahi A, Etemadrezaie H, Ganjeifar B, Gohari B, Abdollahi M, Hassanpour M (2016) Problems in diagnosis and treatment of Retrorectal tumors: our experience in 50 patients. Acta Med Iran 54:644–650

Buchs NC, Gosselink MP, Scarpa CR et al (2016) A multicenter experience with peri-rectal tumors: the risk of local recurrence. Eur J Surg Oncol 42:817–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2016.02.018

Sun W, Ma XJ, Zhang F, Miao WL, Wang CR, Cai ZD (2016) Surgical Treatment of Sacral Neurogenic Tumor: a 10-year experience with 64 cases. Orthop Surg 8:162–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.12245

Hopper L, Eglinton TW, Wakeman C, Dobbs BR, Dixon L, Frizelle FA (2016) Progress in the management of retrorectal tumours. Colorectal Dis 18:410–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13117

Gong L, Liu W, Li P, Huang X (2015) Transsacrococcygeal approach for resection of retrorectal tumors. Am Surg 81:569–572

Simpson PJ, Wise KB, Merchea A, Cheville JC, Moir C, Larson DW, Dozois EJ (2014) Surgical outcomes in adults with benign and malignant sacrococcygeal teratoma: a single-institution experience of 26 cases. Dis Colon Rectum 57:851–857. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000117

Sagar AJ, Koshy A, Hyland R, Rotimi O, Sagar PM (2014) Preoperative assessment of retrorectal tumours. Br J Surg 101:573–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9413

Messick CA, Hull T, Rosselli G, Kiran RP (2013) Lesions originating within the retrorectal space: a diverse group requiring individualized evaluation and surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 17:2143–2152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2350-y

Chéreau N, Lefevre JH, Meurette G, Mourra N, Shields C, Parc Y, Tiret E (2013) Surgical resection of retrorectal tumours in adults: long-term results in 47 patients. Colorectal Dis 15:e476–e482. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12255

Macafee DA, Sagar PM, El-Khoury T, Hyland R (2012) Retrorectal tumours: optimization of surgical approach and outcome. Colorectal Dis 14:1411–1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02994.x

Du F, Jin K, Hu X, Dong X, Cao F (2012) Surgical treatment of retrorectal tumors: a retrospective study of a ten-year experience in three institutions. Hepatogastroenterology 59:1374–1377. https://doi.org/10.5754/hge11686

Li GD, Chen K, Fu D, Ma XJ, Sun MX, Sun W, Cai ZD (2011) Surgical strategy for presacral tumors: analysis of 33 cases. Chin Med J (Engl) 124:4086–4091

Lin C, Jin K, Lan H, Teng L, Lin J, Chen W (2011) Surgical management of retrorectal tumors: a retrospective study of a 9-year experience in a single institution. Onco Targets Ther 4:203–208. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S25271

Gao XH, Zhang W, Fu CG, Liu LJ, Yu ED, Meng RG (2011) Local recurrence after intended curative excision of presacral lesions: causes and preventions. World J Surg 35:2134–2142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-011-1155-y

Dozois EJ, Jacofsky DJ, Billings BJ et al (2011) Surgical approach and oncologic outcomes following multidisciplinary management of retrorectal sarcomas. Ann Surg Oncol 18:983–988. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-010-1445-x

Yang BL, Gu YF, Shao WJ, Chen HJ, Sun GD, Jin HY, Zhu X (2010) Retrorectal tumors in adults: magnetic resonance imaging findings. World J Gastroenterol 16:5822–5829. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i46.5822

Mathis KL, Dozois EJ, Grewal MS, Metzger P, Larson DW, Devine RM (2010) Malignant risk and surgical outcomes of presacral tailgut cysts. Br J Surg 97:575–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6915

Wei G, Xiaodong T, Yi Y, Ji T (2009) Strategy of surgical treatment of sacral neurogenic tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34:2587–2592. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bd4a2b

Pappalardo G, Frattaroli FM, Casciani E et al (2009) Retrorectal tumors: the choice of surgical approach based on a new classification. Am Surg 75:240–248

Grandjean JP, Mantion GA, Guinier D et al (2008) Vestigial retrorectal cystic tumors in adults: a review of 30 cases. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 32:769–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gcb.2008.03.011

Woodfield JC, Chalmers AG, Phillips N, Sagar PM (2008) Algorithms for the surgical management of retrorectal tumours. Br J Surg 95:214–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.5931

Glasgow SC, Birnbaum EH, Lowney JK et al (2005) Retrorectal tumors: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dis Colon Rectum 48:1581–1587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-005-0048-2

Lev-Chelouche D, Gutman M, Goldman G et al (2003) Presacral tumors: a practical classification and treatment of a unique and heterogeneous group of diseases. Surgery 133:473–478. https://doi.org/10.1067/msy.2003.118

Baek SK, Hwang GS, Vinci A, Jafari MD, Jafari F, Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Pigazzi A (2016) Retrorectal tumors: a Comprehensive Literature Review. World J Surg 40:2001–2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3501-6

Toh JW, Morgan M (2016) Management approach and surgical strategies for retrorectal tumours: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 18:337–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13232

Brown IS, Sokolova A, Rosty C, Graham RP (2023) Cystic lesions of the retrorectal space. Histopathology 82:232–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14769

Wang YS, Guo QY, Zheng FH et al (2022) Retrorectal mucinous adenocarcinoma arising from a tailgut cyst: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 14:1072–1081. https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i9.1072

Nicoll K, Bartrop C, Walsh S, Foster R, Duncan G, Payne C, Carden C (2019) Malignant transformation of tailgut cysts is significantly higher than previously reported: systematic review of cases in the literature. Colorectal Dis 21:869–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.14628

Waisman M, Kligman M, Roffman M (1997) Posterior approach for radical excision of sacral chordoma. Int Orthop 21:181–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002640050146

Pennington Z, Reinshagen C, Ahmed AK, Barber S, Goodwin ML, Gokaslan Z, Sciubba DM (2019) Management of presacral schwannomas-a 10-year multi-institutional series. Ann Transl Med 7:228. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.01.66

Dozois EJ, Marcos MDH (2011) Presacral tumors, in The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. Springer, pp 359–374 60

Dozois E, Jacofsky D, Dozois R (2007) The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. Springer, New York, pp 501–514

Kraske P (1886) Zur Exstirpation Hochsitzender Mastdarmkrebse. Arch Klin Chir 33:563–573

Funding

This work was not supported by funding.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by K. F. and M. L. The first draft of the manuscript was written by K. F. and K.E. M. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This retrospective study of clinical data describing outcome of established standard treatment without any experimental arm did not undergo IRB review as ethical approval is commonly not required for these kind of studies.

Informed consent

Patient data of this study were obtained from clinical patients files. The study is descriptive and does not involve any experimental procedures as patient consent to data collection and processing in general, additional informed consent in the specific scenario has not be obtained - for Fig. 2a, b,c informed consent has been obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fechner, K., Bittorf, B., Langheinrich, M. et al. The management of retrorectal tumors – a single-center analysis of 21 cases and overview of the literature. Langenbecks Arch Surg 409, 279 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03471-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03471-0