Abstract

Objective

This study aims to test whether health workers experiencing both depression, anxiety and burnout would show severer burnout symptoms, and the potential moderating effect of anxiety and depression on mindfulness improving burnout.

Methods

This study was conducted in a comprehensive hospital of China in 2016. A total of 924 healthcare professionals were included in this cross-sectional study with a response rate of 82.0%. Maslach Burnout Inventory, Patient Health Questionnaire‐9, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Perceived Stress Scale and Short Inventory of Mindfulness Capability were used to measure burnout, depression, anxiety, perceived stress and mindfulness. Univariate analysis, correlation analysis, mediation analysis and moderated mediation analysis were conducted.

Results

Burnout and anxiety group (BA) and burnout and depression group (BD) reported significantly higher burnout scores compared to the burnout-only group (BO) (59.90 ± 15.700, 56.20 ± 13.190, and 49.99 ± 11.955, respectively). Perceived stress was a mediator between mindfulness and occupational burnout, and depression and anxiety significantly moderated the mediation path between mindfulness and occupational burnout (β for stress in moderated mediation models with depression and anxiety respectively: β = 1.8088, p < 0.001, and β = 1.7908, p < 0.001). For participants who experienced a high level of depression, less occupational burnout was reduced as mindfulness increased. Indirect effect of mindfulness reducing occupational burnout was greater among participants who experienced less anxiety.

Conclusions

Depression and anxiety weakened the mindfulness ability on relieving occupational burnout, which could be the potential mechanism of the worsening effect of depression and anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Occupational burnout is a “prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors” while at work (Maslach 1998) that negatively affects an individual’s health and work life. It was described as emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and reduced personal accomplishment in multidimensional theory of burnout (Maslach 1998). The health workers, who are required to be intensely involved with people, are especially vulnerable to occupational burnout (Maslach and Jackson 1981). Additionally, the stressful work environment that health workers experienced and the direct contact with ill patients suffering from different diseases also drain their emotions so that pose the risk of burnout. Evidence-based researches conducted among nurses (Vasconcelos and Martino 2018), medical residents (Abdulrahman et al. 2018), oncologists (Murali and Banerjee 2018), as well as anaesthetists and intensive care physicians (Mikalauskas et al. 2018) reported noticeable severe occupational burnout status among health workers and proposed intense call for promoting occupational health in medical institution (Creedy et al. 2017; Sibeoni et al. 2019).

Mindfulness, which refers to a non-judgemental attentive awareness of the current moment (Brown and Ryan 2003), is an effective psychosocial coping resource against stress (Kabat-Zinn and Hanh 2009), and a nonnegligible protective factor against burnout (Braun et al. 2017). Promising results for the benefits of mindfulness-based training on occupational burnout among health professional population were addressed in several reviews (Klein et al. 2020; Luken and Sammons 2016; van der Riet et al. 2018). Despite of various training scales and methodology disadvantages, mindfulness practices provided effective skills for many types of health workers, like intern medical practitioners (Ireland et al. 2017), oncology nurses (Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia 2016) and healthcare professionals in intensive care unit (Gracia Gozalo et al. 2019), to manage work-related stress and burnout. As Creswell and Epstein suggested, individuals benefited from mindfulness by improving resilience and attentional capacities under stress (Creswell and Lindsay 2014; Epstein and Krasner 2013). It encourages individuals to confront emotions and feelings from a detached viewpoint, which can help with the management of stress and psychological difficulties (Creswell and Lindsay 2014; Okwaraji and En 2014).

A debate around depression/anxiety-burnout overlap need to be considered in perspectives of mindfulness improving burnout. Depression and anxiety showed many common characters with occupational burnout in previous biological investigations (Marchand et al. 2014), factor analysis (Bianchi and Schonfeld 2018), and theoretical studies (Bianchi et al. 2017). Participants with higher depression scores reported higher scores in occupational burnout as well (Abdulrahman et al. 2018). Occupational burnout and depression were sometimes classed together (Bianchi and Brisson 2019) and were found changing in tandem over time (Bianchi et al. 2015). However, what if a person suffered from both depression/anxiety and burnout? Will depression/anxiety symptoms moderate the effect of mindfulness on occupational burnout? These still need further studies.

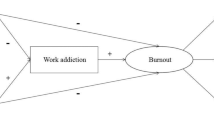

As the “erosive” effect of depression suggested, depression eroded psychological resources, such as cognitive and attributional resources (Joiner Jr 2000), and lead to maladaptive process. This revealed a potential of depression in destroying individual’s coping resources to occupational burnout. Thus, we firstly hypothesized that participants experiencing burnout and depression/anxiety simultaneously would report severer burnout symptoms in a sample of health workers, compared to participants experiencing only burnout. To answer the second scientific question, moderated mediation analysis with depression and anxiety as moderators were performed, and we hypothesized that the effect of mindfulness on burnout could be weakened by severer depression/anxiety symptoms. Considering the potential sharing construct between depression/anxiety and burnout, exploratory structural equation modelling (ESEM) bi-factor analytic approach was firstly used to clarify their relationship. Figure 1 depicts the proposed hypothesis model.

Material and methods

Procedures

This is a cross-sectional study conducted in 2016. A convenience sample of physicians and nurses was recruited from a large public comprehensive hospital in Shandong Province of China. This study was supported by the nursing and medical departments of this hospital. Research assistants were permitted to recruit participants in the department office after the regular daily meeting. Participants were screened by research assistants through verbal inquiry, and participants who met the criteria would step into consent inform process. Potential participants who: (1) were pregnant; (2) were interns; (3) were in-service training; (4) did not contact with patients directly were excluded. The procedure of the study was fully explained to the participants and they were informed that their participation was entirely voluntary. Anonymous questionnaires were kept in sealed envelopes and returned to the research assistants at scheduled time in the department office. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of School of Nursing, Shandong University (Date: Sep-9-2016/No. 2016-R-023).

Measures

Occupational burnout

The Human Service Survey version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) (Maslach 1996) was used to measure occupational burnout for workers in human services. It consists of 22 items, covering 3 general domains: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and reduced personal accomplishment (PA). As the original MBI manual (Maslach et al. 2016) suggested, a higher total score corresponds to higher occupational burnout. The culture-corrected scoring method developed by Li and Li (2006) was used in the current study, in which the three MBI domains were divided into three equal parts (low, moderate and high parts) separately. Participants with at least one domain belongs to the high part were recognized as in high level burnout. This method has been reported to be beneficial and appropriate in Chinese population (Liang and Feng 2017).

Depression and anxiety

Depression was measured by the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ-9) and anxiety was measured by the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7). Higher scores reflect more severe levels of depression/anxiety. The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 are widely used in testing depression/anxiety among various populations and have good reliability and validity. According to research by Spitzer et al. (2006) using a large sample, the sensitivity and specificity are well balanced when the cut-off score is 10. The cut-off score of the PHQ-9 was also set at 10 as recommended by Kroenke et al. (2001).The Cronbach’s α of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 in the current study were 0.879 and 0.905, respectively.

Mindfulness

The Short Inventory of Mindfulness Capability (SIM-C), a shorter version of the widely used Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), was used to assess mindfulness (Duan and Li 2016). The subscales measure three facets of mindfulness: describing, acting with awareness, and non-judging of experience. The SIM-C has good convergent validities and internal consistency, and has been reported to have a strong relationship with mental health in Chinese samples (Duan and Li 2016; Lin et al. 2018). A high score indicates well-cultivated mindfulness. The Cronbach’s α of the SIMC in the current study was 0.789.

Stress

The shortened version of Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) was used to measure the level of perceived stress in participants. PSS-4 consists of four items, two positive and two negative, and a higher total score indicates a greater degree of stress. A satisfactory psychometric property of this scale has been confirmed in a Chinese sample (Leung et al. 2010). The Cronbach’s α for the positive and negative subscales were 0.692 and 0.707 for PSS-4 in the present study.

Demographic and job-related characteristics

Demographics, including age, gender, marriage status, education level, BMI, smoking and drinking status, were recorded. Research has linked job-related characteristics with occupational burnout and mental health; therefore, data regarding the work time, work form (night shift or day shift), and monthly income were collected.

ESEM factor analyses

Considering a debate around depression/anxiety-burnout overlap is still in air (Bianchi and Schonfeld 2018; Bianchi et al. 2017; Koutsimani et al. 2019; Leiter and Durup 1994), a factor analysis was conducted to clarify the construct of PHQ-9, GAD-7 and MBI. In this study, we used exploratory structural equation modelling (ESEM) (Aparuhov and Muthen 2009) in Mplus 7.0. An ESEM model with four factors was fitted with RMSEA = 0.059, SRMR = 0.035, CFI = 0.891, TLI = 0.862. In the four factors, PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were loaded in one factor, and three dimensions of MBI were loaded substantially in the other three factors. The results of the ESEM analysis indicated that the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 did not share a construct with MBI in this study, which allowed the further regression analysis.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive, univariate, and correlational analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 23.0 software. Means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables while frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Univariate analyses were conducted using independent sample t and Chi-square tests, and correlation analyses were conducted using Pearson’s correlation analysis. The mediation analysis and moderated mediation analysis were undertaken using Models 4 and 8 of Hayes’s PROCESS, respectively. Using moderated mediation model allowed us to determine whether a mediation path could be moderated by depression and anxiety, which were each entered in the models as moderators. Bootstrapping with 5000 samples was used. A two-tailed α = 0.05 was set for all the analyses and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results

Preliminary analyses

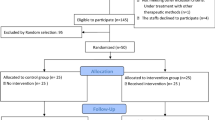

A total of 1127 physicians and nurses who work in different wards were reached and 924 were finally included with a positive response rate of 82.0%. The mean age of this sample was 27.92 (SD 6.811, range 20–66) years, and 705/924 (76.3%) of them were nurses. Other demographic data, job-related information, and mean scores of the measurements are listed in Table 1. According to Li and Li’s (2006) evaluation methods, 63.6% (588/924) of the participants were recognized in high level of occupational burnout. A total of 136 (14.7%) participants reported high level of anxiety with GAD-7 ≥ 10 and 169 (18.3%) reported high level of depression with PHQ-9 ≥ 10. Among the participants with high level of occupational burnout, 33.16% also experienced high degrees of depressive or anxiety symptoms. To clarify the co-occurrence status of anxiety, depression and occupation burnout, five groups were categorized according to the binary anxiety, depression, and burnout variables: the low burnout group (participants with low level of burnout, LB), burnout-only group (participants with high level of burnout but low levels of anxiety and depression, BO), burnout and anxiety group (participants with high levels of burnout and anxiety but low level of depression, BA), burnout and depression group (participants with high levels of burnout and depression but low level of anxiety, BD), and burnout, anxiety and depression group (participants with high levels of burnout, anxiety and depression, ABD).

The five groups differed significantly in their burnout, anxiety, depression, stress, and mindfulness scores (see Table 2). Overall, those in burnout groups scored significantly higher on burnout, anxiety, depression, and stress measures, and lower on the mindfulness measure, compared to those in LB group. Among the five groups, the ABD group scored the highest on all variables except mindfulness. Both BA and BD reported higher burnout scores compared to the BO group. Participants in the ABD and BD groups scored the lowest on mindfulness.

Correlation analysis

Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed the associations between burnout, anxiety, depression, stress, and mindfulness, which was shown in Table 3. As expected, anxiety, depression, and stress positively associated with burnout (r = 0.518, p < 0.001; r = 0.502, p < 0.001; r = 0.451, p < 0.001) while mindfulness negatively associated with it (r = − 0.341, p < 0.001). Furthermore, mindfulness negatively associated with stress, anxiety, and depression (r = − 0.368, p < 0.001; r = − 0.346, p < 0.001; r = − 0.407, p < 0.001).

Testing for mediation

Mediation analysis was conducted using Model 4 of PROCESS following Hayes’s procedure. After controlling for age, gender, occupation, work shift, anxiety, and depression, mindfulness was found negatively associated with perceived stress (β = − 0.0894, p < 0.001). When mindfulness and perceived stress were both included as independent variables, mindfulness negatively associated with occupational burnout (β = − 0.3762, p = 0.001) while perceived stress positively associated with occupational burnout (β = 1.8253, p < 0.001). The mediation test showed ab = − 0.1631, SE = 0.04, 95% CI (− 0.2541, − 0.0941), and the mediation effect accounted for 30.27% of the total effect. Consequently, perceived stress mediated the association between mindfulness and occupational burnout (shown in Fig. 2).

Moderated mediation analyses

We ran moderated mediation analysis using Model 8 of PROCESS to examine whether the relation between mindfulness, perceived stress, and occupational burnout was moderated by depression. Firstly, a model with perceived stress as dependent variable ran. In this model, both mindfulness, depression and mindfulness * depression significantly associated with perceived stress (β = − 0.0822, p < 0.001; β = 0.1120, p < 0.001; β = 0.0058, p = 0.0406), which means depression could moderate the relationship between mindfulness and perceived stress. Then, perceived stress, mindfulness, depression and mindfulness * depression were included into a model with burnout as dependent variable. Even though there was a moderator in the model, perceived stress could associate with occupational burnout significantly (β = 1.8088, p < 0.001, seen in Table 4). The conditional indirect effect reported a lower mediation effect for high level of depression [β = − 0.1026, SE = 0.0513, 95% CI (− 0.2189, − 0.0131), seen in Table 5]. The results indicated that for participants who experienced a high level of depression, less occupational burnout was reduced as mindfulness increased.

A similar moderating effect was found for anxiety. Anxiety could also moderate the mediation relationship between mindfulness, perceived stress, and occupational burnout. Conditional indirect effect analysis further revealed that the overall indirect effect was greater among participants who experienced less anxiety [β = − 0.2046, SE = 0.0528, 95% CI (− 0.3222, − 0.1134)]. The details are provided in Tables 4 and 5.

Discussion

Occupational burnout, depression and anxiety are all of great significance for occupational health. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the worsening effects of depression and anxiety on occupational burnout through the mediation path of mindfulness, perceived stress and burnout. After clarifying the different construct between depression, anxiety and burnout, this study found that mindfulness could relieve occupational burnout by reducing perceived stress, but this ability of mindfulness can be weakened by depression and anxiety. This finding enriched the discussion that focuses on occupational burnout and emotional problems besides the depression-burnout overlap, and provided a new perspective for occupational health maintaining.

Severer symptoms of burnout and perceived stress were observed in ABD, BD and BA groups compared to LB and BO groups, which supported our first hypothesis. Depression, anxiety correlated with occupational burnout positively, which was reported in previous studies (Creedy et al. 2017; Ortega-Campos et al. 2019) and was also an important premise in the worsening effect. In previous studies, depression and burnout were found similar alternations in the processes of attention, memory, and interpretation related to ambiguous information (Bianchi et al. 2018, 2020). Anxiety symptoms were reported negatively associated with professional efficacy, while positively associated with emotional exhaustion (Ding et al. 2014). From a biological view, the underlying shared genes between them could lead individuals’ susceptibility to depression, anxiety and occupational burnout (Mosing et al. 2018). Additionally, we could say the “erosive” effect (Joiner Jr 2000) we mentioned before worked to some extent. In this perspective, a depressive episode erodes an individual’s psychosocial resources, and fewer buffers would be left to against future psychological distress. Occupational burnout, therefore, became a difficult distress to cope with for individuals with eroded psychological resources. Occupational burnout related to the decision of intention to quit (Knani et al. 2018), while depression and anxiety correlated to poor well-being and higher suicidal ideation (Ballard et al. 2014; Lew et al. 2019). To avoid severer symptoms caused by the worsening effects, combined interventions focused on both depression, anxiety and occupational burnout should be a prior choose.

Perceived stress mediated the relationship between mindfulness and occupational burnout, which was consistent with results in previous interventional studies (Ireland et al. 2017; Vella and McIver 2019). Intriguingly, this mediation effect provided us a path to explore the mechanism for how depression and anxiety aggravated occupational burnout symptoms among healthcare professionals, which was firstly reported, to the best of our knowledge. In detail, depression and anxiety weakened the effect of mindfulness reducing stress, which limited the relief of occupational burnout. Depression and anxiety hinder the effects of mindfulness in the current study, which can be owing largely to negative automatic thoughts. According to Beck’s cognitive theory of depression, the core thinking for depression was negative automatic thoughts (Beck 1983; Beck and Clark 1997). People with anxiety also tended to report frequent negative thinking (Mahmoud et al. 2015; Paloş and Vîşcu 2014). Individuals with depression or anxiety often expressed negative self-appraisal and experienced a sense of hopelessness in their lives (Lew et al. 2019). Involuntary negative thoughts gave rise to a biased responding pattern and maladaptive coping strategies (Beck and Clark 1997; Mahmoud et al. 2015), which shown as less mindfulness available in the current study. Studies using electroencephalogram and imaging supported the theory partly, in which they reported that depression and negative thinking influenced brain activity and regions associated with mindfulness, such as gray matter volume (Du et al. 2015; Tang et al. 2015). In addition, mindfulness, a limited psychological resource, was not considered powerful enough to against both depression, anxiety and occupational burnout. Competition for mindfulness could be another way to explain the worsening effect of depression and anxiety, but more theoretical studies need to be developed.

Notably particularly, healthcare workers in developing countries such as China, where there are limited mental health services, depend more on internal psychosocial resources rather than external supportive resources. The harm caused by the worsening effect of depression or anxiety would be worse for them. Combined with the intense hospital patient relationship, it’ll be particularly important to prevent these psychological distresses. The current study emphasized that healthcare professionals with both depression, anxiety and occupational burnout were high-risk group. And to adopt multi-interventions focusing on both depression, anxiety and occupational burnout together would be much more effective than a single one.

Consequently, it is necessary to be on high alert for signs of depression, anxiety and occupational burnout among healthcare workers. For individuals at high risk of combined psychological distress, approaches besides mindfulness training should also be recommended. Receiving external support resources from family, friends and hospital managers appears to be a better way for healthcare professionals to cope with depression, anxiety and occupational burnout.

Despite being a unique study, the current research has certain inherent limitations. First, the possible overlap between depression and burnout may limit the generalization of the results. Even though a distinct construct between PHQ-9, GAD-7 and MBI-HSS was clarified in the current day using factor analysis, data-based method was only one way to understand the relationships between depression, anxiety and burnout. Theoretical studies still need to be conducted to discuss this question. Second, although the current cross-sectional study conducted a moderated mediation model and provided a useful explanatory mechanism, using a cross-lagged design would be more reliable for verifying the direction of the relation between depression, anxiety and occupational burnout. And the effect of the moderated mediation model was small and should be interpreted with caution. Third, using mindfulness-cultivating interventions instead of a self-reported mindfulness measure would be more persuasive in clarifying the acting pathway and yield more reliable results. Therefore, in future research, moderated mediation models based on randomised controlled trials need to be conducted to test our results. To use the version of MBI for medical personnel in future studies may be also a better choice to collect burnout syndrome in health professionals. Finally, the generalizability of the findings may be limited by the sole hospital where participants were recruited. However, sole hospital also allowed the researchers to build a supportive relationship with nursing and medical departments to ensure a high response rate (82.0% in the current study). The accessibility was important to ensure high response rate as well because the research assistants in the current study were permitted to recruit in the department office, which was convenient for the potential participants to participate and return the questionnaires.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found the worsening effect of depression and anxiety on occupational burnout symptoms. And it firstly, to our knowledge, revealed that depression and anxiety weakened mindfulness stress-reducing effect in relieving occupational burnout among healthcare professionals. Our findings suggested an integrated perspective in preventing and treating occupational burnout.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Abdulrahman M, Nair SC, Farooq MM, Al Kharmiri A, Al Marzooqi F, Carrick FR (2018) Burnout and depression among medical residents in the United Arab Emirates: a multicenter study. J Fam Med Primary Care 7(2):435

Aparuhov T, Muthen B (2009) Exploratory structural equation modeling: structural equation modeling. Multidiscip J 16(3):397–438

Ballard ED, Ionescu DF, Voort JLV, Niciu MJ, Richards EM, Luckenbaugh DA, Zarate CA Jr (2014) Improvement in suicidal ideation after ketamine infusion: relationship to reductions in depression and anxiety. J Psychiatr Res 58:161–166

Beck AT (1983) Cognitive therapy of depression: new perspectives. In: Clayton PJ, Barett JE (eds) Treatment of depression. Old controversies and new approaches. Raven Press, New York, pp 265–284

Beck AT, Clark DA (1997) An information processing model of anxiety: a automatic and strategic processes. Behav Res Ther 35(1):49–58

Bianchi R, Brisson R (2019) Burnout and depression: causal attributions and construct overlap. J Health Psychol 24(11):1574–1580

Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS (2018) Burnout-depression overlap: nomological network examination and factor-analytic approach. Scand J Psychol 59(5):532–539

Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E (2015) Is burnout separable from depression in cluster analysis? A longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50(6):1005–1011

Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Vandel P, Laurent E (2017) On the depressive nature of the “burnout syndrome”: a clarification. Eur Psychiatry 41:109–110

Bianchi R, Laurent E, Schonfeld IS, Verkuilen J, Berna C (2018) Interpretation bias toward ambiguous information in burnout and depression. Personal Individ Differ 135:216–221

Bianchi R, Laurent E, Schonfeld IS, Bietti LM, Mayor E (2020) Memory bias toward emotional information in burnout and depression. J Health Psychol 25:1567–1575

Braun SE, Auerbach SM, Rybarczyk B, Lee B, Call S (2017) Mindfulness, burnout, and effects on performance evaluations in internal medicine residents. Adv Med Educ Pract 8:591

Brown KW, Ryan RM (2003) The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(4):822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Creedy D, Sidebotham M, Gamble J, Pallant J, Fenwick J (2017) Prevalence of burnout, depression, anxiety and stress in Australian midwives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(1):13

Creswell JD, Lindsay EK (2014) How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 23(6):401–407

Ding Y, Qu J, Yu X, Wang S (2014) The mediating effects of burnout on the relationship between anxiety symptoms and occupational stress among community healthcare workers in China: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 9(9):e107130

Du X, Luo W, Shen Y, Wei D, Xie P, Zhang J, Qiu J (2015) Brain structure associated with automatic thoughts predicted depression symptoms in healthy individuals. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 232(3):257–263

Duan W, Li J (2016) Distinguishing dispositional and cultivated forms of mindfulness: item-level factor analysis of five-facet mindfulness questionnaire and construction of short inventory of mindfulness capability. Front Psychol 7:1348

Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J (2016) Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention on oncology nurses’ burnout and compassion fatigue symptoms: a non-randomized study. Int J Nurs Stud 64:98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.10.002

Epstein RM, Krasner MS (2013) Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad Med 88(3):301–303

Gracia Gozalo RM, Ferrer Tarrés JM, Ayora Ayora A, Alonso Herrero M, Amutio Kareaga A, Ferrer Roca R (2019) Application of a mindfulness program among healthcare professionals in an intensive care unit: effect on burnout, empathy and self-compassion. Med Intensiva 43(4):207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medin.2018.02.005

Ireland MJ, Clough B, Gill K, Langan F, O’Connor A, Spencer L (2017a) A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness to reduce stress and burnout among intern medical practitioners. Med Teach 39(4):409–414

Joiner TE Jr (2000) Depression’s vicious scree: Self-propagating and erosive processes in depression chronicity. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 7(2):203–218

Kabat-Zinn J, Hanh TN (2009) Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness: Delta

Klein A, Taieb O, Xavier S, Baubet T, Reyre A (2020) The benefits of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout among health professionals: a systematic review. Explore (NY) 16(1):35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2019.09.002

Knani M, Fournier P-S, Biron C (2018) Psychosocial risks, burnout and intention to quit following the introduction of new software at work. Work 60(1):95–104

Koutsimani P, Anthony M, Georganta K (2019) The relationship between burnout, depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 10:284

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9):606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Leiter MP, Durup J (1994) The discriminant validity of burnout and depression: a confirmatory factor analytic study. Anxiety Stress Coping 7(4):357–373

Leung DY, Lam TH, Chan SS (2010) Three versions of Perceived Stress Scale: validation in a sample of Chinese cardiac patients who smoke. BMC Public Health 10:513. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-513

Lew B, Huen J, Yu P, Yuan L, Wang D-F, Ping F, Jia C-X (2019) Associations between depression, anxiety, stress, hopelessness, subjective well-being, coping styles and suicide in Chinese university students. PLoS One 14(7):e0217372

Li YX, Li YM (2006) Developing the diagnostic ctiterion of job burnout (in Chinese). Psychol Sci 29(1):148

Liang XC, Feng XL (2017) Research progress on job burnout among nurses: a systematic review (in Chinese). Chin Nurs Manag 11:19

Lin P, Wang Y, Yang B, Cao F (2018) Reliability and validity of the Short Inventory of Mindfulness Capability Chinese version applied in multi ethnic college students. Nurs Res 32(24):61–65

Luken M, Sammons A (2016) Systematic review of mindfulness practice for reducing job burnout. Am J Occup Ther 70(2):7002250020p7002250021–7002250020p7002250010

Mahmoud JS, Staten RT, Lennie TA, Hall LA (2015) The relationships of coping, negative thinking, life satisfaction, social support, and selected demographics with anxiety of young adult college students. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 28(2):97–108

Marchand A, Durand P, Juster R-P, Lupien SJ (2014) Workers’ psychological distress, depression, and burnout symptoms: associations with diurnal cortisol profiles. Scand J Work Environ Health 40(3):305–314

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP (1996) Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd edn. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Maslach C (1998) A multidimensional theory of burnout. Theor Organ Stress 68:85

Maslach C, Jackson SE (1981) The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav 2(2):99–113

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL (2016) Maslach Burnout Inventory™ (MBI). http://www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory. Accessed 20 June 2019

Mikalauskas A, Benetis R, Širvinskas E, Andrejaitienė J, Kinduris Š, Macas A, Padaiga Ž (2018) Burnout among anesthetists and intensive care physicians. Open Med 13(1):105–112

Mosing MA, Butkovic A, Ullen F (2018) Can flow experiences be protective of work-related depressive symptoms and burnout? A genetically informative approach. J Affect Disord 226:6–11

Murali K, Banerjee S (2018) Burnout in oncologists is a serious issue: what can we do about it? Cancer Treat Rev 68:55–61

Okwaraji F, En A (2014) Burnout and psychological distress among nurses in a Nigerian tertiary health institution. Afr Health Sci 14(1):237–245

Ortega-Campos E, Albendín-García L, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Monsalve-Reyes C, de la Fuente-Solana EI (2019) A multicentre study of psychological variables and the prevalence of burnout among primary health care nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(18):3242

Paloş R, Vîşcu L (2014) Anxiety, automatic negative thoughts, and unconditional self-acceptance in rheumatoid arthritis: a preliminary study. ISRN Rheumatol 2014:317259

Sibeoni J, Bellon-Champel L, Mousty A, Manolios E, Verneuil L, Revah-Levy A (2019) Physicians’ perspectives about burnout: a systematic review and metasynthesis. J Gen Intern Med 34(8):1578–1590

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Tang Y-Y, Hölzel BK, Posner MI (2015) The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci 16(4):213–225

van der Riet P, Levett-Jones T, Aquino-Russell C (2018) The effectiveness of mindfulness meditation for nurses and nursing students: an integrated literature review. Nurse Educ Today 65:201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.018

Vasconcelos EM, Martino MMF (2018) Predictors of burnout syndrome in intensive care nurses. Rev Gaucha Enferm 38(4):e65354. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2017.04.65354

Vella E, McIver S (2019) Reducing stress and burnout in the public-sector work environment: a mindfulness meditation pilot study. Health Promot J Aust 30(2):219–227

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by FL, YW, MZ and BY. The first draft of the manuscript was written by YS and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Project administration and supervision were performed by FC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of School of Nursing, Shandong University (Date: Sep-9-2016 /No. 2016-R-023).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., Liu, F., Wang, Y. et al. Mindfulness improves health worker’s occupational burnout: the moderating effects of anxiety and depression. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 94, 1297–1305 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01685-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01685-z