Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of basic military training (BMT) is to enable the recruited soldiers to acquire basic military skills and develop the required physical fitness. This training is accompanied by heightened physical stress and the risk of injury and excessive stress symptoms (I&ESS). The objective of this study was to examine the extent to which the level of physical fitness at the beginning of BMT affects the incidence of I&ESS and resultant absence from duty.

Methods

The data of a total of 774 subjects (age 20.5 ± 2.2) from 8 subsequent BMT quarters were analysed. The medical diagnoses made during the consulting hours of the unit physicians were reviewed for I&ESS and the kinds of injuries incurred and the sick leave pronounced were documented. The level of physical fitness per quarter was then categorised by means of the total numbers of points achieved during the standard basic fitness test (BFT). This categorisation was finally used as a basis for an analysis of the lost days in relation to the level of physical fitness.

Results

255 of the 774 subjects (32.9%) suffered an I&ESS. 60% of all the I&ESS were located at lower extremity. There was a significant increase in the length of absence from duty among the group with the lowest level of physical fitness.

Conclusions

The analysis revealed that the level of physical fitness at the beginning of BMT has a significant influence on the length of absence from duty due to I&ESS. Moreover, 60% of the injuries were lower extremity injuries, which show the specific significance they have for limitations during BMT. Overall, this reveals the necessity for appropriate preventive measures (additional fitness training, adjustment of requirements) to be implemented so that recruits with a low level of fitness can complete BMT with as few injuries as possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A high level of physical fitness is a prerequisite in some professions for performing profession-related tasks. A work-related high level of physical fitness is especially a key component for meeting workplace demands in the police, fire brigade and armed forces (Knapik et al. 2004; von Heimburg et al. 2006; Holmér and Gavhed 2007; Elsner and Kolkhorst 2008; Williams-Bell et al. 2010). Soldiers must especially meet the necessity to conduct task-specific activities (such as extinguishing a fire, handling a firearm safely) at the same time as taking account of the physical component. This meets all kinds of soldiers independently of their branches (e.g., army, navy, air force, marines, etc.).

In addition, the increasing lack of exercise among juveniles and young adults is resulting in a reduction in physical resilience among potential first-time employees (Graf et al. 2006; Leyk et al. 2006; Kettner et al. 2012). Employees are especially unable to reliably perform complex activities like those mentioned above when they take up a new occupation. This is why first-time employees in the military initially undergo several months of basic military training (BMT). The goal of BMT is to enable them to acquire basic military skills and raise their levels of physical fitness. Injuries and excessive stress symptoms (I&ESS) during BMT can reduce the time available for training and thus its overall quality significantly. American and Israeli studies have isolated various risk factors that influence the incidence of I&ESS during BMT (Schmidt Brudvig et al. 1983; Macleod et al. 1999; Beck et al. 2000; Knapik et al. 2001b, 2012; Rauh et al. 2006; Shaffer et al. 2006; Finestone et al. 2008; Trone et al. 2014; Cameron and Owens 2016). Besides other risk factors, such as being female (Macleod et al. 1999; Knapik et al. 2001a), underweight or overweight (Finestone et al. 2008; Knapik et al. 2012), active tobacco smoking (Friedl et al. 1992; Knapik et al. 2001b; Lappe et al. 2001), being of a certain age (Lappe et al. 2001; Knapik et al. 2012) or belonging to a specific ethnic group (Friedl et al. 1992; Lappe et al. 2001; Knapik et al. 2012), physical fitness at the beginning of the training period has been revealed to be a key predictor for a higher incidence of I&ESS during BMT. However, there is a fundamental difference between nations with respect to the first months of military training, recruitment (professional army versus conscript army) and the length of BMT. The objective of this study is therefore to determine the influence of the initial level of fitness of recruits on the incidence of I&ESS during BMT in the Bundeswehr.

Methodology

During eight coherent training quarters (IV/2012 to III/2014), data from Bundeswehr recruits who voluntary participated were included in this study. The physical fitness was tested with the standard Basis-Fitness-Test (BFT) (Chief of Defence 2013) at the beginning of the BMT and additional information was taken from their health files. The basic training was conducted in the training companies of Tank Battalion 203 (5./203) and Armoured Infantry Battalion 212 (5./212), which are based at the same barracks in Augustdorf, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Two criteria for inclusion in the study were the successful completion of BMT and the issue of a written statement confirming that participation in the study was voluntary. In total, 774 subjects [age 20.5 ± 2.2 years, body mass index (BMI) 23.5 ± 2.8 kg/m2] were included in the study. Thus, 67% of all the recruits undergoing their BMT during that period participated in this study. There were no significant differences in the age and body measurements of those who participated in the study and those who did not (Table 1).

The medical data were reviewed for periods of absence from duty due to I&ESS, and the periods were documented. As a specific military feature, periods of full administrative leave were documented (in the civilian health system, such leave corresponds to a general inability to work) alongside periods of limited fitness for duty (e.g., exemption from outside duty activities, marching, physical training or field duty).

Sub-analysis groups were defined for I&ESS that were attributed to general military training in the field, obstacle course training, self-protection training in CBRN hazard situations, marksmanship training (all four categorised as general military training) and mandatory physical training. Acoustic trauma incurred during marksmanship training and blisters incurred during marches were excluded.

The initial level of physical fitness was documented on the basis of the BFT results (Leyk et al. 2006). This standard test consists of an 11 × 10-m sprint, a flexed arm hang and a 1000-m run and is fundamentally conducted at the beginning of BMT. Based on the BFT results, fitness levels were categorised by quarters, and the lost days due to I&ESS within each quarter were then analysed by means of ANOVA and a subsequent Dunnett-T post hoc analysis. Furthermore, the I&ESS were analysed with regard to the body regions affected and their incidence during the various kinds of training. For the exposition analysis, the numbers of I&ESS were put into relation with periods of exposure. The calculations of the periods of exposure were based on the number of hours for which each kind of training was scheduled to be conducted in the duty rosters, and lost days due to illness were factored in for each recruit.

This study was approved by the ethics commission of Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg (file no: 111/12).

Results

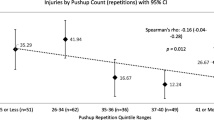

255 subjects (32.9% of the total sample) reported to the unit physicians with 397 I&ESS during BMT. The average sick leave was 6.0 ± 7.9 days per recruit, and 60% of all the injuries were lower extremity injuries (Fig. 1). The trunk (22%), upper extremity (13%) and head (4%) were clearly less affected. The majority of the I&ESS (57%) were incurred during general military training. 10% of I&ESS were attributed to mandatory physical training, while the physicians documented no specific causes for the remaining 33%.

During the study and in consideration of the fitness for duty of the participants, a total of 283,831.1 h of general military training were conducted, the largest share of which was assigned to marksmanship training (138,082.3 h) and field training (134,411.4 h). Obstacle course training (5446.1 h) and CBRN defence training (5891.3 h) constituted only a minor share of the training time. Mandatory physical training, amounting to 18,959.8 h, made up a rather small part of the total time for BMT. The time each recruit spent on training was 178.4 h for marksmanship training, 173.7 h for field training, 7.6 h for self-protection training in CBRN hazard situations, 7.0 h for obstacle course training and 24.5 h for mandatory physical training.

The analysis of I&ESS cases per 1000 h of specific training showed an incidence of 1.09 I&ESS/1000 h during general military training and 4.17 I&ESS/1000 h during mandatory physical training. A sub-analysis of the incidence of I&ESS during general military training, which comprised marksmanship training, CBRN defence training, obstacle course training and field training, revealed that a high number of I&ESS were incurred during obstacle course training, while no cases were incurred during marksmanship and CBRN defence training (Fig. 2). An increase in the number of I&ESS was also observed during the summer and winter quarters, especially as a result of field training and mandatory physical training (Table 2).

The ANOVA analysis revealed that physical fitness had a significant influence on the length of absence from duty in association with the total number of lost days due to I&ESS. The average number of lost days was significantly higher in the quarter in which the level of fitness was the lowest than in the other quarters (see Table 3). This was confirmed in the subsequent Dunnett-T post hoc analysis.

Discussion

The present study shows that the initial level of physical fitness has a significant influence on lost days due to I&ESS during BMT in the German Army.

Overall, BMT in its present form is estimated to cause substantially less injuries than in 2008/09 (Sammito 2011). A decrease in the average number of injuries from 2.27/1000 h to 1.45/1000 h has been documented. The most likely reason for this is the change in the training concept during BMT, which is now based on a new shooting training concept. In this new concept, a higher number of training hours are scheduled for shooting, with the result that the number of hours for field training has been reduced during which particularly more injuries are caused. This was also revealed by the data analysis.

This study has shown that general military training was the main cause of injuries (57% of all injuries). In contrast, the incidence of injuries during general military training per 1000 h, with the average being 1.09/1000 h, is rather low and can be ascribed to the high total number of training hours. Moreover, general military training can be divided into four sub-groups, and the number of injuries sustained is different in each. Marksmanship and CBRN defence training have proved to cause particularly few injuries, with no I&ESS having been found to be incurred from it. In contrast with more than 18 I&ESS/1000 h, the very high injury rate for obstacle course training stands out. Because of the low number of hours allocated for obstacle course training, the injuries incurred during it carry considerably less weight in the overall analysis of all injuries. Even if a reduction of training with high injury rate makes sense from the preventive medicine point of view, the obstacle course is a particularly good form of training for various movement sequences that are specifically required in military operations.

Furthermore, an increase in I&ESS was noted during seasonal quarters. It is conceivable that this was due to the weather. The influence of the weather on the surface conditions has already been identified as a cause of a greater injury during mandatory physical training at the same base (Gundlach et al. 2012). Since general military training takes place outside, it is likely that (weather-related) changes in surface conditions in the winter months (due to snow and ice) and the summer months (highest precipitation rates of the year) may also be the reason for an increase in the risk of injury. The high number of I&ESS noted during the summer months can also be ascribed to other climatic conditions, such as the effects of higher temperatures on the body, which speed up the rate at which recruits become exhausted and increase the risk of injury, as found among recruits in the US military (Knapik et al. 2002).

The analysis furthermore showed that the level of fitness of the recruits at the start of BMT had a significant influence on the incidence of I&EES. The overall number of lost days for recruits with the lowest level of fitness was significantly higher than that for recruits with a higher level of fitness. The increase in the overall number of lost days also resulted in a loss of training time, and this reduced the progress made in training by individual recruits. Moreover, lost days must be expected to lead to a further lowering of a recruit’s (current) level of fitness and, in turn, an increase in the risk of their incurring (additional) I&ESS. This can lead to a further rise in the difference in physical fitness between recruits who incur injuries and others who do not lose days.

This result allies with the findings of the US Armed Forces (Knapik et al. 2001a, b). To reduce the incidence of I&ESS, the level of fitness of recruits was raised by putting them into a pre-training, and this significantly lowered the incidence of injuries during BMT (Knapik et al. 2001a, 2003). It can be assumed that this would also be the case with recruits in the German Army.

Summary

Altogether, the results show that BMT in its present form causes fewer injuries when the injury rate are compared to those compiled in earlier surveys and that this development is linked to the change in the training concept with more hours allocated to training that is less prone to cause injuries. Increase in numbers during certain seasons can probably be attributed to unfavourable weather conditions. Special attention should be paid, however, to the level of fitness of recruits, as it has a significant influence on the incidence of I&ESS and the lost days they cause.

References

Beck TJ, Ruff CB, Shaffer RA, Betsinder K, Trone DW, Brodine SK (2000) Stress fracture in military recruits: gender differences in muscle and bone susceptibility factors. Bone 27:437–444

Cameron KL, Owens BD (eds) (2016) Musculoskeletal injuries in the military. Springer, New York

Chief of Defence (2013) Weisung zur Ausbildung, zum Erhalt der Individuellen Grundfertigkeiten und zur körperlichen Leistungsfähigkeit (Weisung IGF/KLF). Berlin

Elsner KL, Kolkhorst FW (2008) Metabolic demands of simulated fire-fighting tasks. Ergonomics 51:1418–1425

Finestone A, Milgrom C, Evans R, Yanovich R, Constantini N, Moran DS (2008) Overuse injuries in female infantry recruits during low-intensity basic training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40:S630–S635

Friedl KE, Nouvo JA, Patience TH, Dettori JR (1992) Factors associated with stress fracture in young army women: indications for further research. Mil Med 157:334–338

Graf C, Dordel S, Koch B, Predel H-G (2006) Bewegungsmangel und Übergewicht bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Dtsch Z Sportmed 57:220–225

Gundlach N, Sammito S, Böckelmann I (2012) Risk factors for accidents during sport while serving in German Armed Forces. Sportverletz Sportschaden 26:45–48

Holmér I, Gavhed D (2007) Classification of metabolic and respiratory demands in fire fighting activity with extreme workloads. Appl Ergon 38:45–52

Kettner S, Wirt T, Fischbach N, Kobel S, Kesztyüs D, Schreiber A, Drenowatz C, Steinacker JM (2012) Nesessity for physical activity promotion in German Children. Dtsch Z Sportmed 63:94–101

Knapik JJ, Canham-Chervak M, Hoedebecke E, Hewitson WC, Hauret K, Held C, Sharp MA (2001a) The fitness training unit in U.S. Army basic combat training: physical fitness, training outcomes, and injuries. Mil Med 166:356–361

Knapik JJ, Sharp MA, Cnham-Chervak M, Hauret K, Patton JF, Jones BH (2001b) Risk factors for training-related injuries among men and women in basic combat training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33:946–954

Knapik JJ, Canham-Chervak M, Hauret K, Laurin MJ, Hoedebecke E, Craig S, Montain SJ (2002) Seasonal variations in injury rates during US Army basic combat training. Ann Occup Hyg 46: 15–23

Knapik JJ, Hauret KG, Arnold S, Canham-Chervak M, Mansfield AJ, Hoedebecke EL, McMillian D (2003) Injury and fitness outcomes during implementation of physical readiness training. Int J Sport Med 24:372–381

Knapik JJ, Reynolds KL, Harman E (2004) Soldier load carriage: historical, physiological, biomechanical and medical aspects. Mil Med 169:45–56

Knapik J, Montain SJ, McGraw S, Grier T, Ely M, Jones BH (2012) Stress fracture risk factors in basic combat training. Int J Sport Med 33:940–946

Lappe JM, Stegmann MR, Recker RR (2001) The impact of lifestyle factors on stress fractures in female Army recruits. Osteoporos Int 12:35–42

Leyk D, Rohde U, Gorges W, Ridder D, Wunderlich M, Dinklage C, Sievert A, Rüther T, Essfeld D (2006) Physical performance, body weight and BMI of young-adult in Germany 2000–2004: results of the Physical-Fitness-Test Study. Int J Sport Med 27:642–647

Macleod MA, Houston AS, Sanders L, Anagnostopoulos C (1999) Incidence of trauma related stress fractures and shin splints in male and female army recruits: retrospective case study. BMJ 318:29

Rauh MJ, Macera CA, Trone DW, Shaffer RA, Brodine SK (2006) Epidemiology of stress fracture and lower-extremity overuse injury in female recruits. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38:1571–1577

Sammito S (2011) Risk of injury during combat training—assessment of the relative rate of injuries during four successive basis training periods. Wehrmed Mschrift 55:90–93

Schmidt Brudvig TJ, Gudger TD, Obermeyer L (1983) Stress fractures in 295 trainees: a one-year study of incidence as related to age, sex, and race. Mil Med 148:666–667

Shaffer RA, Rauh MJ, Brodine SK, Trone DW, Macera CA (2006) Predictors of stress fracture susceptibiliy in young female recruits. Amer J Sport Med 34:108–115

Trone DW, Cipriana DJ, Raman R, Wingard DL, Shaffer RA, Macera CA (2014) Self-reported smoking and musculoskeletal overuse injury among male and female U.S. Marine Corps Recruits. Mil Med 179:735–743

von Heimburg ED, Rasmussen AKR, Medbø JI (2006) Physio-logical responses of firefighters and performance predictors during a simulated rescue of hospital patients. Ergonomics 49:111–126

Williams-Bell FM, Boisseau G, McGill J, Kostiuk A, Hughson RL (2010) Air management and physiological responses during simulated firefighting tasks in a high-rise structure. Special section: behavioural effects and drive-vehicle-environment modelling in modern automotive systems. Appl Ergon 41:251–259

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Müller-Schilling, L., Gundlach, N., Böckelmann, I. et al. Physical fitness as a risk factor for injuries and excessive stress symptoms during basic military training. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 92, 837–841 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01423-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01423-6