Abstract

Objectives

Duration at sea was investigated as a potential chronic stressor amongst seafarers in addition to the mediating roles of previous seafaring experience and hardiness between duration and stress.

Methods

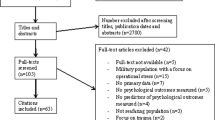

In a cross-sectional design, questionnaires were emailed to 53 tanker vessels in an international shipping company with questions relating to duration at sea, perceived stress, personality hardiness and work characteristics. The sample comprised 387 seafarers (98 % male) including ratings, crew, officers, engineers, and catering staff that had been on board their ship between 0 and 24 weeks.

Results

Duration at sea was unrelated to self-reported perceived stress, even after controlling for previous seafaring experience and hardiness. Additional regression analyses demonstrated that self-reported higher levels of resilience, longer seafaring experience and greater instrumental work support were significantly associated with lower levels of self-reported stress at sea.

Conclusions

These results imply that at least for the first 24 weeks at sea, exposure to the seafaring environment did not act as a chronic stressor. The confined environment of a ship presents particular opportunities to introduce resilience and work support programmes to help seafarers manage and reduce stress, and to enhance their well-being at sea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Isolated confined environments (ICE) come in various forms: polar expeditions, a submarine deployment, a job on an offshore oil-drilling platform or a mission in space (Sandal et al. 2006). Individuals in such environments both live and work in a confined space, separated from their family and friends, without the ability to leave the workplace for prolonged periods. Moreover, they live in close quarters with the same individuals and are exposed to the same physical environment for weeks and months at a time. A number of environmental stressors that are present are therefore chronic.

Chronic work stressors can be defined as long-lasting events or characteristics of the environment, which place individuals at risk of experiencing stress and reduced well-being (Hepburn et al. 1997). Over time they can wear down an individual’s resilience (Hobfoll 1989; Selye 1956). Indeed, prolonged exposure to even minor daily hassles can be exceptionally stressful (e.g. Haukka et al. 2011; Hu et al. 2011), often leading to negative outcomes for both the individuals and an organisation, such as psychological distress (Szeto and Dobson 2013; Wang 2005; Wang and Patten 2001), burnout (Steinhardt et al. 2011), employee absence (Aldana and Pronk 2001; Virtanen et al. 2007) and reduced work performance (Hon and Chan 2013).

It is well known that individuals vary in their response to challenging circumstances that may generate stress. One of the most widely accepted theoretical frameworks from which to understand this variance is the person–environment fit model (Cooper and Marshall 1976). Within this theoretical framework, stress is seen as arising from an interaction between the individual and the environment, emphasising both characteristics of the workplace, as well as individual personality traits, which may protect against stress in certain situations.

Chronic stressors may yield physical and psychological health effects for those working in ICEs. For example, Reini (2010) asserts that submariners, by the nature of their work, may be more vulnerable to developing hypercortisolism, a state of chronically elevated cortisol levels. In relation to the environment of a ship, Oldenburg et al. (2010) suggest that shipboard stress may result in isolation and fatigue, which impact the health of seafarers on board.

It has been suggested that prolonged exposure to the seafaring environment will lead to greater stress (e.g. Carter 2005; Comperatore et al. 2005). According to the Cardiff Seafarer Fatigue Study (Smith et al. 2006), one in four seafarers reported falling asleep on watch; approximately 50 % reported working more than 85 h per week; over half of respondents reported that their working hours had increased over the previous 10 years; and approximately half considered their working hours to represent a danger.

Dissimilar to most other occupations, seafarers are periodically at the workplace during both working and non-working hours, 24 h per day, and are therefore isolated from the rest of the world for long periods of time (Hult 2012; Carotenuto et al. 2012). The majority of ships’ staff work 7 days per week and are allocated time off at the end of their voyage; contracts vary substantially, so that some seafarers work on board for 2–4 weeks at a time, while others work on board from 3 months to 2 years; moreover, shore leave for seafarers is extremely difficult due to intense workload while ships are in port, decrease in crewing numbers, port locations and environments, and recent security measures (Idnani 2013). While many seafarers can communicate with family members using telephones, mobile phones, satellite phones and email, conditions of access to email facilities may vary significantly (Kahveci 2011). Oldenburg et al. (2009) reported separation from family as a significant stressor amongst a sample of 134 seafarers, with the average shipboard stay (months/year) of officers lasting substantially shorter than that of non-officers (4.8 vs. 8.3 months per year); and the average shipboard stay of Europeans lasting only half as long as that of non-European seamen (4.9 vs. 9.9 months per year).

While, as outlined above, it has been suggested that prolonged exposure to the seafaring environment will lead to greater stress, Elo (1985) reported that perceived stress and duration at sea were unrelated amongst a sample of Finnish seafarers. Nonetheless, several changes have been implemented within the seafaring industry in the 30 years since this study, such as reduced crew numbers (Roberts et al. 2010), decreased turnaround times (Kahveci 2000) and extended working hours (Bloor et al. 2000). The requirements of ships’ officers and crew are also increasing, including operating the ship’s machinery and equipment and ensuring proper functioning of all of the ship’s devices and machinery (Borodina 2013). Thus, duration at sea may have a greater influence on stress now than was found almost found 30 years ago.

In Hobfoll’s (1989) Conservation of Resources theory, he emphasises the need for individuals to take the time to recover and replenish resources that have been worn down, in order to cope with long-lasting stressors (Sonnentag and Fritz 2007). Of course in an ICE such as a ship, opportunities for engaging in leisure activities of choice are extremely restricted, so that mentally detaching from work may be more difficult in such environments. Previous experience of a stressor can also act to protect against stress by equipping individuals with knowledge of what to expect and how to cope with potential stressors (Ellis and Boyce 2008; Hopwood and Treloar 2008). It is possible that seafarers with greater experience may develop strategies for dealing with stress over long journeys.

The positive psychology movement (Seligman 2011) has given impetus to researchers who are investigating ICEs to move beyond attempting to minimise negative reactions to stress and to incorporate the benefits that can be gained through working in such contexts. For example, Suedfeld (2001) argues for what he terms a ‘salutogenic’ approach to stress that emphasises the characteristics of people who can thrive on missions in environments such as the Antarctic.

Resilience is a trait that has received considerable attention in the positive psychology sphere and has been defined as the ability to ‘bounce back’ from adversity (Luthans et al. 2006). Schetter and Dolbier (2011) attempted to identify a multitude of facets of resilience that may foster the ability to cope despite repetitive and long-lasting or chronic demands. One such facet was the relatively stable personality trait, referred to as ‘hardiness’ (Kobasa 1979). ‘Hardy’ individuals not only have been shown to be more resistant against stress, but also tend to see potential stressors as an opportunity for growth and personal development (Maddi and Harvey 2006).

Hardiness is conceptualised as having three distinct components: control, commitment and challenge (Kobasa 1979), each of which protects against maladaptive responding in the face of difficulties. Control describes the general belief that one can influence environmental outcomes, even when difficult situations may facilitate passivity and powerlessness (Maddi 2006). Commitment indicates a tendency to avoid retreating into isolation under stress and to actively engage in the world (Maddi 2002). Finally, a strong sense of challenge is the tendency to view change and stressful events as potential opportunities for personal growth and learning, rather than as a threat.

As many seafarers are deployed for long periods at sea, it is important to examine how perceived stress varies over time in this context in order to determine the optimum length of exposure, in addition to the characteristics which may act as protective factors against perceived stress, such as hardiness described above. The present study examines these questions in the context of duration at sea amongst seafarers in an international gas and crude oil shipping company. As proposed by Oldenburg et al. (2013), there is currently a significant dearth of research assessing the complex work of seafarers on board.

The present study attempts to build on previous research by investigating the duration of exposure to a seafaring environment and how this relates to how seafarers perceive stress. Based on previous theory, it was hypothesised that a longer duration at sea would be associated with greater stress amongst seafarers. Second, it was hypothesised that higher levels of hardiness amongst seafarers would equip them to manage stress more effectively, thus mediating the relationship between duration at sea and perceived stress. Third, it was hypothesised that those with previous seafaring experience would have learned effective coping strategies for dealing with prolonged exposure in an ICE, and thus this would also act as a protective factor against stress over a long duration at sea. Finally, in line with the person–environment fit model, specific characteristics of the work environment are also likely to influence individuals’ experience of stress. Our fourth hypothesis was therefore that exposure to what is perceived to be a more positive working environment is likely to be less stressful than exposure to what is perceived to be a less positive work environment.

Method

Ethics

The study was approved by the School of Psychology Ethics Committee, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Questionnaires were emailed to the captains of 53 tanker vessels in an international gas and crude oil shipping company with a request to inform crew and upload the questionnaire onto the ships’ web-based servers. Information relating to the study and contact details for the primary researcher and academic supervisor were provided with the online administered questionnaire (see “Appendices 1, 2”).

Survey Monkey (2014) was used for data collection, which is a third-party online survey software, and not linked to any of the systems of the international shipping company from which the sample was derived for this study. Due to requirements for confidentiality and anonymity within the shipping company, demographic data in the questionnaire on age ranges were collected rather than specific ages. Data collected for the surveys did not contain names, email addresses or phone numbers. This anonymity ensured that answers could not be traced back to any individual participant. Employees of the international shipping company were not involved in analyses of individual data, but only in planning and coordination of the study and jointly reviewing results and interpretation.

Participants and procedure

This study employed a cross-sectional design. As outlined above, at the commencement of the study, a communication went out from the fleet operations of the shipping company to the captains of 53 tanker vessels to request them to inform crew about the questionnaire and upload it onto the ships’ web-based servers. These 53 vessels comprised the entire managed fleet, so no selection or exclusion of any vessel or individual on board these vessels was made. The researchers of this study did not have access to the fleet employee data, which is maintained by the manning agencies and fleet operations of the shipping company. For confidentiality and anonymity purposes within the organisation therefore, the study was arranged so that the researchers would not know whether all members of the crew had been informed that the study was taking place. Therefore, a response/return rate could not be defined by the researchers.

Crew members were provided with one month to complete the questionnaire on the shipboard computer or their own laptop. A total of 423 questionnaires were returned from 51 vessels. Due to missing responses on all of the variables of interest, 36 participants were excluded entirely from the analyses and the total sample size was reduced to 387. Additionally, as a result of missing responses on some of the variables of interest, the number of participants varied for the different analyses by using pairwise deletion on SPSS. See Table 1 in the results section for demographics.

Materials

The questionnaire included demographic items such as age, gender, job description and ethnicity. Job description categories included ‘officer, engineer’; ‘rating, crew’; and ‘catering’; officers and engineers were analysed as one group due to the work tasks that are similar across these job types (see Table 2). As mentioned previously, due to the requirements for confidentiality and anonymity within the organisation, age ranges were asked for rather than specific ages. These age ranges were 18–29, 30–39, 40–64 and 65+, representing, respectively, young adulthood, thirties, middle age and aged (PsycINFO 2014). Ethnic and job identifiers were self-reported via the categories used by the organisation. All questionnaires were administered in English.

Duration at sea

The survey included one question concerning the number of weeks participants had been on board since their last shore leave at the time of survey completion.

Seafaring experience

One question asked participants to indicate how long they had worked as a seafarer (<1, 1–4, 5–10, 11–20, >20 years).

Personality hardiness

To assess hardiness, the Dispositional Resilience Scale-15 (DRS-15) was used (Bartone 2007). This scale consists of 15 items, negatively and positively worded, covering three components of hardiness: commitment, control and challenge. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which statements were true on a four-point Likert scale (0 = not at all true, 3 = completely true). An example item is: ‘Most of my life gets spent doing things that are meaningful’. Some debate exists regarding the use of total scores of hardiness rather than three independent components (e.g. Funk 1992). Hystad et al. (2010), however, recently demonstrated that a hierarchical model is a better fit to the data than a three-factor model (i.e. commitment, control, challenge).

Perceived stress

Perceived stress was measured using a four-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) developed by Cohen et al. (1983). Participants answered two negatively and two positively worded questions about the extent to which general situations in the last month were appraised as stressful. An example item is ‘In the last month, how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?’ Questions were answered on a five-point Likert scale (0 = Never, 4 = Quite Often), and an overall total of stress was obtained from the mean of the addition of all four items. Internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha was somewhat low (α = .57) in the present sample, but comparable to estimates in the literature (Cohen and Williamson 1988).

Work characteristics

The Employees Survey is an annual survey of work attitudes and experiences completed anonymously by the organisation’s employees. From this broad-ranging survey, we identified 16 items, with the same Likert scale response options, which we felt related to relevant characteristics in the work environment. This subset of the Employees Survey was also included in the survey and was factor-analysed to identify any meaningful factors that might emerge.

Assumptions

Prior to each analysis, tests were performed to ensure that the data did not violate any assumptions associated with the analysis in question. In each case, Levene’s test of equality of error variances indicated homogeneity of variance and visual inspection of scatterplots implied linear relationships between the variables of interest. The Durbin–Watson test was used to show that for each analysis, there was independence of observations and histograms were visually scanned for homoscedasticity and normality. In each case, the assumptions were met.

Results

The results section is divided into four sections. The first section details the characteristics of participants; second, psychometric properties of the instruments are outlined; third, analyses of potential covariates are presented; and finally, the analyses testing each hypothesis is reported, alongside additional analyses that were carried out in order to investigate the strongest predictors of perceived stress within the sample. Mean and standard deviations for perceived stress and duration at sea are outlined in Table 1. Table 3 is a summary (n, mean, median, SD, min, max) for all scale variables.

Participants

The sample comprised 387 seafarers (98 % male) including catering staff, ratings, crew and officers, engineers that had been on board their ship between 0 and 24 weeks. For the analyses of potential covariates, participants who identified as Mixed (n = 6), Latino/Hispanic (n = 3) and African (n = 10) were excluded as a result of too few participants in these categories to conduct reliable statistical analyses, as well as those identifying as ‘Other’ (n = 50).

Psychometric properties

Dispositional Resilience Scale-15

Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the subscales was .65 for commitment, .57 for control and .57 for challenge. The use of the total score increased this score to .72. Additionally, analyses revealed that total hardiness predicted the dependent variable better than each component of hardiness alone. Therefore, only analyses with total hardiness scores are reported here (Cronbach’s alpha = .72). Acceptable test–retest reliability has previously been demonstrated for this scale (Pearson correlation coefficient .78; Bartone 2007).

Work characteristics

The 16 work environment-related items from the Employees Survey were subjected to exploratory factor analysis (EFA, principal axis factoring) with orthogonal (varimax) rotation (see Table 4). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .93, and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ 2 (120) = 2597.17, p < .001), indicating the appropriateness of the data to undergo this sort of analysis. A total of five items were eliminated because they did not meet the minimum criteria of having a primary factor loading of at least .5, with at least .2 above its second highest loading, leaving 10 items (emboldened) in the final solution (see Table 4).

Cattell’s scree test and Kaiser’s criterion indicated that a two-factor solution best represented the data, accounting for 51.7 % of the variance. Moreover, each factor could be interpreted in a meaningful and coherent way. Factor 1 (5 items) accounted for 27 % of the total variance and was interpreted as ‘job satisfaction’. The second factor (five items) that emerged was interpreted as ‘instrumental support’, explaining 25 % of total variance. Cronbach’s alpha was .83 and .77, respectively, indicating an acceptable level of reliability for these scales (see Table 4).

Covariates

The second stage of analyses was to identify whether any of the demographic variables (gender, age, ethnicity, job type, location) were related to perceived stress, in order to control for them in later analyses. Gender and location were omitted from these analyses as 98 % of participants were male and 84 % were ‘on passage’ (see Table 1).

A series of one-way analyses of variance indicated that ethnicity was significantly related to perceived stress [F (2, 307) = 6.6, p < .01] with East Asians reporting the most perceived stress, followed by South Asians and those identifying as Caucasian. Job and perceived stress were also significantly associated [F (2, 376) = 5, p = .01], such that officers were on average less stressed than both catering and rating staff. Finally, Pearson’s correlation indicated that age was negatively correlated with perceived stress, with younger participants reporting more stress than older participants [r(374) = −.16, p < .01; see Table 1].

Age was entered into each analysis below as a covariate. Dummy variables were created for ethnicity (African, Caucasian, East Asian, Other, Latino/Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Mixed) and job type (crew, catering) and also controlled for in the regression analyses.

Hypotheses testing

Hypothesis 1

Participants had been at sea for a mean duration of 6.45 weeks (SD 5.09). In order to investigate Hypothesis 1 that a longer duration at sea predicts greater stress amongst seafarers, a linear regression was performed with the two variables. A total of 372 participants were included in the analysis after pairwise deletion. After controlling for age, job and ethnicity, duration at sea did not significantly predict perceived stress, F(1, 363) = 1.49, p = .22. Figure 1 displays a scatter plot of perceived stress and duration at sea for all individuals. It is also important to note that the mean PSS score of 5.27 (SD = 2.72) is within the norm range and in fact slightly lower than that reported in a recent English population norm sample (Warttig et al. 2013; M = 6.11, SD = 3.14), indicating that our sample of seafarers’ perceived stress was not higher than this population norm.

Hypothesis 2

In order to investigate a potential mediating relationship between duration at sea and perceived stress, a second hierarchical regression was performed, entering hardiness into the model, followed by duration at sea. A total of 354 participants were included in this analysis. After controlling for age, job and ethnicity, duration at sea was found not to explain any additional variance in perceived stress, F(1, 363) = .37, p = .55, adj R 2 = .2. It is also important to note that the mean DRS score of 30.00 (SD = 5.44) was within the norm range of that reported by Taylor et al. (2013) and Eid and Morgan (2006) in military samples.

Hypothesis 3

To explore whether seafaring experience mediates the relationship between duration at sea and perceived stress, a hierarchical regression, entering seafaring experience into the model first, indicated that the addition of duration at sea did not lead to any significant increase in variance of stress explained, F(1, 362) = 1.2, p = .27, adj R 2 = .05.

Hypothesis 4

Although duration at sea was unrelated to perceived stress, additional analyses were carried out to establish whether work-related and personal factors were associated with perceived stress. A backward regression analysis was performed in order to identify the model of best fit for predicting perceived stress. Listwise deletion was selected to ensure that each model predicted contained the same participants and 337 participants remained in the analysis. Comparisons of the standard error of estimate revealed that total hardiness predicted the dependent variable better than each component of hardiness alone. Table 5 depicts the three models that were produced and the amount of variance explained by each model (adjusted R2). Model 3 appeared to be the best fit; it included instrumental support, hardiness and seafaring experience, explaining 22 % of the variance in perceived stress. Job satisfaction and age were excluded from this model as they did not explain any additional variance above and beyond that of support, hardiness and experience.

Discussion

The present study investigated duration at sea and how it related to stress amongst seafarers in an international shipping company. Duration at sea was not related to self-reported stress, even when accounting for the effects of hardiness and previous seafaring experience. The current findings imply that for the first 6 months of a voyage, exposure to the ship environment does not in and of itself exact a toll on merchant marine seafarers and suggests that the relationship between duration at sea and perceived stress may only become evident on deployments longer than this. While average levels of stress and hardiness were within the normal range, less experienced seafarers, those who were lower in hardiness and those who reported less instrumental work support were significantly more likely to experience higher levels of self-reported stress at sea, regardless of duration of deployment.

That duration at sea did not relate to perceived stress differs from studies showing that longer military deployments increase the risk of psychological distress (Shen et al. 2010). Sandal (2000) cautions against generalising across ICEs and argues that it is important to take the physical and group characteristics into account. Therefore, differences in the objective environment, organisational climate and even job requirements may therefore contribute towards whether and the extent to which duration at sea is experienced as a chronic stressor. The type of deployments that soldiers experience may account for the differences between the findings of this study and those of studies examining military deployments therefore in that such military deployments may contain elements of trauma and shock and be more stressful than non-military seafaring deployments. What is more surprising is that even for those low in hardiness (i.e. control, commitment, challenge) and with less seafaring experience, duration at sea did not appear to be related to stress. We had expected that without the personal resources of hardiness and experience, the isolated and confined nature of a ship would act as a chronic stressor. This was not the case.

The current study provides support for the person–environment fit model (Cooper and Marshall 1976) in that personality characteristics, environmental aspects, such as having the necessary tools and information to carry out one’s job and having the cooperation of others on board (‘instrumental support’), and work exposure factors each contributes towards perceptions of stress. Previous seafaring experience was negatively related to stress such that those with least experience were more likely to experience greater stress. This may reflect two processes. First, those who are unsuited to a seafarer career and who find long voyages stressful may leave the profession early in their career, leaving only those who are a good ‘fit’. Second, as Bonanno and associates suggest (2010), previous experience might give individuals the opportunity to develop coping mechanisms and knowledge of what to expect, both of which may act as resources to deal with stress at sea. In either case, this study identifies individuals with less seafaring experience as particularly vulnerable to stress at sea, making them an important group to target with preventative interventions. The results from the study also add to existing knowledge of the relationship between hardiness and perceived stress (e.g. Andrew et al. 2008; Escolas et al. 2013; Paulik 2001). Having a hardy personality—high in control, commitment and challenge—seems to equip seafarers with the resources to cope well on board regardless of the duration of their deployment.

As outlined above, having the necessary tools and information to carry out one’s job and having the cooperation of others on board (‘instrumental support’) also seem to decrease perceptions of stress. This makes intuitive sense in that without the means to carry out one’s job effectively, one is likely to encounter more stressful circumstances. Interestingly, while instrumental support was related to job satisfaction, job satisfaction was not in itself related to stress. This implies that while job satisfaction is no doubt important in its own right, it does not provide a buffer to stress; rather, more direct instrumental support is required to achieve this.

Our results about the patterning of stress are also interesting. Different ethnic groups may have distinctive stressors and stress reactions (MacLachlan 2006). While South Asian and East Asian seafarers reported higher perceived stress than other ethnic groups, the pattern of relationships between the variables we measured did not vary with ethnicity. That is, the same factors had a similar influence on stress for all ethnic groups, even though their resulting effects differed. This implies that similar preventative interventions may help to ameliorate stressful experiences across different ethnic groups. It may also be the case that for our respondents at least, the ‘corporate culture’ had an overriding effect on ethnic differences per se. We also found that caterers and ratings, crew were the job categories that reported the most perceived stress. It may be that these cadres feel that they have less control and/or less status aboard ship. In a study of Danes and Filipinos on board Danish vessels, Knudsen (2004) found that the hierarchical order on board frequently overlapped with ethnicity, highlighting that Danes were employed on more advantageous terms than their colleagues, including more senior positions, better pay, full contracts and shorter terms of duty. Similarly, Oldenburg et al. (2009) reported the average shipboard stay of officers lasting substantially shorter than that of non-officers and the average shipboard stay of Europeans lasting only half as long as that of non-European seamen. As proposed by Oldenburg et al. (2009), this social gradient likely constitutes a significant stress factor aboard ships. Given the range of psychological and physical health problems associated with seafaring (MacLachlan et al. 2012), it is important to target the most at-risk groups for preventative interventions. However, as we have argued elsewhere, these aspects of ‘organisational culture’ should be addressed not just at ‘ship level’ but throughout shipping organisations’ different and interacting levels (MacLachlan et al. 2013).

Implications

Stress in the workplace can have negative consequences for the individual and the organisation (Hon and Chan 2013; Steinhardt et al. 2011; Szeto and Dobson 2011). Considering the confined nature of a vessel and the limited opportunities for engaging in activities of choice during a voyage, managing stress is of vital importance. As researchers have recently pointed out (MacLachlan et al. 2013), the confined nature of a vessel also offers a unique opportunity to develop occupational health programmes that comprehensively integrate work and leisure. This study identifies hardiness as a key factor in reducing feelings of being unable to cope with demands and in developing a resilient and satisfied workplace. Although Kobasa (1979) initially proposed hardiness as a relatively stable personality trait, there has been some evidence to suggest that hardy traits can be developed through training (Maddi et al. 2009). Future research should therefore address the effectiveness of hardiness training within a seafaring population.

It is important to consider our findings in the light of several limitations associated with the current study. First, a cross-sectional design was used, which precluded causation being determined between duration at sea and stress. Future research would benefit from examining duration at sea and stress in a longitudinal design with repeated measures, to more adequately assess variations in stress over the duration at sea. Further, there were a variety of ethnic groups participating in the study, and as all questionnaires were administered in English, the risk of the impact of language issues on results and internal consistency of scales cannot be ruled out. In relation to the low internal consistency of the PSS-4, similar estimates have been found in previous studies (Cohen and Williamson 1988). Further research on the validity of this measure is recommended. Another limitation is our inability to assess a response rate for the study. For confidentiality and anonymity purposes within the organisation, the study was arranged so that the researchers would not know whether all members of the crew had been informed that the study was taking place. Without this information, it cannot be ruled out that a sampling bias was present and those who did participate in the study were particularly resilient. It is, however, noteworthy that responses were received from crew members on 51 of the 53 ships that were available to us to survey from the fleet. It is recommended that future studies also take into consideration potential covariates such as quality of sleep, obesity, exercise, drinking and smoking habits that are likely to be of relevance to perceived stress and resilience. Particularly in a marine environment, these factors would be of interest.

A particular strength of the study is its ecological validity, given that individuals completed the questionnaire while they were on board ship. The lack of such ecological validity has been an important and prevalent criticism of studies with seafaring samples (e.g. Bridger and Bennett 2011; Guo and Liang 2012; Haka et al. 2011; Hockey et al. 2003; Röttger et al. 2013). It is also possible that the requirements for confidentiality and anonymity within the organisation—noted above—actually attracted more participants to the study. Indeed, the sample size in the current study (N = 387) is greater than has been attained in any previously published studies that collected comparable data from this hard-to-reach population (e.g. Barnes 1984; Bridger and Bennett 2011; Bhattacharya and Tang 2013; Guo and Liang 2012).

Conclusion

Isolated from their family, friends and the rest of the world, seafarers are required to live and work contained within a vessel for weeks and months at a time. The findings from the current study suggest that within the first six months at sea, individuals are no more likely to experience greater stress after a longer period of sea than those towards the beginning of their deployment. With regard to prevention of perceived stress of seafarers, it is important that individuals have the personal resources to cope with demands as well as the organisational resources to carry out their job effectively. Our results suggest that the well-being of seafarers may be enhanced by strengthening their resilience and their perceived instrumental support at work. We recommend that resilience training be undertaken with seafarers and its benefits evaluated through a longitudinal design, with particular attention being given to less experienced crew, to job type on board ship and to ethnicity. This will require a mode of intervention which is equally accessible to crew from different cultural backgrounds, and different levels of experience, education and training.

References

Aldana SG, Pronk NP (2001) Health promotion programs, modifiable health risks, and employee absenteeism. J Occup Environ Med 43(1):36–46

Andrew ME, McCanlies EC, Burchfiel CM, Charles L, Hartley TA, Fekedulegn D, Violanti JM (2008) Hardiness and psychological distress in a cohort of police officers. Int J Emerg Ment Health 10(2):137–148

Barnes BL (1984) Relationship between mental health and job efficiency. Acta Psychiatr Scand 69(6):466–471. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1984.tb02521.x

Bhattacharya S, Tang L (2013) Middle managers’ role in safeguarding OHS: the case of the shipping industry. Saf Sci 51(1):63–68. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2012.05.015

Bloor M, Thomas M, Lane T (2000) Health risks in the global shipping industry: an overview. Health Risk Soc 2(3):329–340. doi:10.1080/713670163

Bonanno GA, Brewin CR, Kaniasty K, La Greca AM (2010) Weighing the costs of disaster: consequences, risks and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychol Sci Pub Interest 11(1):1–49. doi:10.1177/1529100610387086

Borodina NV (2013) Use of sail training ship in seafarers’ professional education. Asia-Pac J Mar Sci Educ 3(1):87–96

Bridger RS, Bennett AI (2011) Age and BMI interact to determine work ability in seafarers. Occup Med 61(3):157–162. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqr003

Carotenuto A, Molino I, Fasanaro AM, Amenta F (2012) Psychological stress in seafarers: a review. Int Marit Health 63(4):188–194

Carter T (2005) Working at sea and psychosocial health problems: report of an international maritime health association workshop. Travel Med Infect Dis 3:61–65. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2004.09.005

Cohen S, Williamson G (1988) Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S (eds) The social psychology of health. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 31–67

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24(4):385–396

Comperatore CA, Rivera P, Kingsley L (2005) Enduring the shipboard stressor complex: a systems approach. Aviat Space Environ Med 76(6):108–118

Cooper CL, Marshall J (1976) Occupational sources of stress: a review of the literature relating to coronary heart disease and mental ill health. J Occup Psychol 49(1):11–28. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1976.tb00325.x

Eid J, Morgan CA (2006) Dissociation, hardiness, and performance in military cadets participating in survival training. Mil Med 171:436–442

Ellis BJ, Boyce W (2008) Biological sensitivity to context. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 17(3):183–187. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00571.x

Elo A (1985) Health and stress of seafarers. Scand J Work Environ Health 11(6):427–432. doi:10.5271/sjweh.2204

Escolas SM, Pitts BL, Safer MA, Bartone PT (2013) The protective value of hardiness on military posttraumatic stress symptoms. Mil Psychol 25(2):116–123. doi:10.1037/h0094953

Funk SC (1992) Hardiness: a review of theory and research. Health Psychol 11(5):335–345. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.11.5.335

Guo J, Liang G (2012) Sailing into rough seas: Taiwan’s women seafarers’ career development struggle. Women’s Stud Int Forum 35(4):194–202. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2012.03.016

Haka M, Borch DF, Jensen C, Leppin A (2011) Should I stay or should I go? Motivational profiles of Danish seafaring officers and non-officers. Int Marit Health 62(1):20–30

Haukka E, Leino-Arjas P, Ojajärvi A, Takala E, Viikari-Juntura E, Riihimäki H (2011) Mental stress and psychosocial factors at work in relation to multiple-site musculoskeletal pain: a longitudinal study of kitchen workers. Eur J Pain 15(4):432–438. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.09.005

Hepburn C, Loughlin CA, Barling J (1997) Coping with chronic work stress. In: Gottlieb BH (ed) Coping with chronic stress. Plenum Press, New York, pp 343–366

Hobfoll SE (1989) Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol 44(3):513–524. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hockey GJ, Healey A, Crawshaw M, Wastell DG, Sauer J (2003) Cognitive demands of collision avoidance in simulated ship control. Hum Factors 45(2):252–265. doi:10.1518/hfes.45.2.252.27240

Hon AY, Chan WW (2013) The effects of group conflict and work stress on employee performance. Cornell Hosp Q 54(2):174–184. doi:10.1177/1938965513476367

Hopwood M, Treloar C (2008) Resilient coping: applying adaptive responses to prior adversity during treatment for hepatitis C infection. J Health Psychol 13(1):17–27. doi:10.1177/1359105307084308

Hu Q, Schaufeli WB, Taris TW (2011) The job demands–resources model: an analysis of additive and joint effects of demands and resources. J Vocat Behav 79(1):181–190. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.12.009

Hult C (ed) (2012) Swedish seafarers and seafaring occupation 2010: A study of work-related attitudes during different stages of life at sea. Kalmar Maritime Academy. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:730758/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2015

Hystad SW, Eid J, Johnsen BH, Laberg JC, Bartone PT (2010) Psychometric properties of the revised Norwegian dispositional resilience (hardiness) scale. Scand J Psychol 51(3):237–245. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00759.x

Idnani S (2013) The sea as a working place. In: Carter T, Schreiner A (eds) Textbook of maritime medicine, 2nd edn. Norwegian Centre for Maritime Medicine, Bergen

Irish Statute Book (1998) Merchant Shipping Act (chapter 179, sections 47, 100 and 216); Merchant shipping (training, certification and manning) regulations. http://www.mpa.gov.sg/sites/pdf/msa_sl01_training_cert_and_manning.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2015

Kahveci E (2000) Fast turnaround ships and their impact on crews. Seafarers International Research Centre (SIRC), Cardiff University, UK. http://www.sirc.cf.ac.uk/uploads/publications/Fast%20Turnaround%20Ships.pdf. Accessed 26 Nov 2014

Kahveci E (2011) Seafarers & communication. ITF Seafarers’ Trust, London, UK. http://workinglives.org/fms/MRSite/Research/wlri/WORKS/Seafarers%20and%20Communication%20Report.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2015

Knudsen F (2004) If you are a good leader I am a good follower; Working and leisure relations between Danes and Filipinos on board Danish vessels. http://static.sdu.dk/mediafiles/Files/Om_SDU/Institutter/Ist/MaritimSundhed/Rapporter/report92004.pdf. Accessed 27 Jan 2015

Kobasa SC (1979) Stressful life events, personality, and health: an inquiry into hardiness. J Pers Soc Psychol 37(1):1–11. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.1.1

Luthans F, Vogelgesang GR, Lester PB (2006) Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Hum Resour Dev Rev 5(1):25–44. doi:10.1177/1534484305285335

MacLachlan M (2006) Culture and health, 2nd edn. Wiley, Chichester

MacLachlan M, Kavanagh W, Kay A (2012) Maritime health: a review with suggestions for research. Int Marit Health 63:1–6

MacLachlan M, Cromie S, Liston P, Kavanagh B, Kay A (2013) Psychosocial and organisational aspects of work at sea. In: Carter T, Schreiner A (eds) Textbook of maritime medicine, 2nd edn. Norwegian Centre for Maritime Medicine, Bergen

Maddi SR (2002) The story of hardiness: twenty years of theorizing, research, and practice. Consult Psychol J Pract Res 54(3):173–185. doi:10.1037/1061-4087.54.3.173

Maddi SR (2006) Hardiness: the courage to grow from stresses. J Posit Psychol 1(3):160–168. doi:10.1080/17439760600619609

Maddi SR, Harvey RH (2006) Hardiness considered across cultures. In: Wong PP, Wong LJ (eds) Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping. Spring, Dallas, pp 409–426

Maddi SR, Harvey RH, Khoshaba DM, Fazel M, Resurreccion N (2009) Hardiness training facilitates performance in college. J Posit Psychol 4(6):566–577. doi:10.1080/17439760903157133

Office for National Statistics, UK (2010) Standard occupational classification 2010: volume 1; Structure and descriptions of unit groups. Palgrave Macmillan, UK. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/classifications/current-standard-classifications/soc2010/soc2010-volume-1-structure-and-descriptions-of-unit-groups/index.html#1. Accessed 26 Jan 2015

Oldenburg M, Jensen HJ, Latza U, Baur X (2009) Seafaring stressors aboard merchant and passenger ships. Int J Public Health 54(2):96–105. doi:10.1007/s00038-009-7067-z

Oldenburg M, Baur X, Schlaich C (2010) Occupational risks and challenges of seafaring. J Occup Health 52(5):249–256

Oldenburg M, Hogan B, Jensen HJ (2013) Systematic review of maritime field studies about stress and strain in seafaring. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 86:1–15. doi:10.1007/s00420-012-0801-5

Paulik K (2001) Hardiness, optimism, self-confidence and occupational stress among university teachers. Stud Psychol 43(2):91–100

PsycINFO (2014) About PsycINFO. https://www.library.nhs.uk/hdas/Content/html/AboutDB/PsycINFO.html. Accessed 27 Jan 2015

Reini SA (2010) Hypercortisolism as a potential concern for submariners. Aviat Space Environ Med 81(12):1114–1122. doi:10.3357/ASEM.2875.2010

Roberts SE, Jaremin B, Chalasani P, Rodgers SE (2010) Suicides among seafarers in UK merchant shipping, 1919–2005. Occup Med 60(1):54–61. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqp133

Röttger S, Vetter S, Kowalski JT (2013) Ship management attitudes and their relation to behavior and performance. Hum Factors 55(3):659–671. doi:10.1177/0018720812461271

Sandal GM (2000) Coping in Antarctica: is it possible to generalize results across settings? Aviat Space Environ Med 71(9):37–43

Sandal GM, Leon GR, Palinkas L (2006) Human challenges in polar and space environments. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 5:281–296. doi:10.1007/s11157-006-9000-8

Schetter CD, Dolbier C (2011) Resilience in the context of chronic stress and health in adults. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 5(9):634–652. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00379.x

Seligman MEP (2011) Flourish: a new understanding of happiness and well-being—and how to achieve them. Nicholas Brealey, London

Selye H (1956) The stress of life. McGraw-Hill, New York

Shen Y, Arkes J, Kwan B, Tan L, Williams TV (2010) Effects of Iraq/Afghanistan deployments on PTSD diagnoses for still active personnel in all four services. Mil Med 175(10):763–769

Smith A, Allen P, Wadsworth E (2006) Seafarer fatigue: The Cardiff Research Programme. Centre for Occupational and Health Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. http://orca.cf.ac.uk/48167/1/research_report_464.pdf. Accessed 26 Nov 2014

Sonnentag S, Fritz C (2007) The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J Occup Health Psychol 12(3):204–221. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204

Steinhardt MA, Smith Jaggars SE, Faulk KE, Gloria CT (2011) Chronic work stress and depressive symptoms: assessing the mediating role of teacher burnout. Stress Health J Int Soc Investig Stress 27(5):420–429. doi:10.1002/smi.1394

Suedfeld P (2001) Applying positive psychology in the study of extreme environments. J Hum Perform Extreme Environ 6(1):21–25

Survey Monkey (2014) Survey Monkey. https://www.surveymonkey.com/. Accessed 11 May 2015

Szeto AH, Dobson KS (2013) Mental disorders and their association with perceived work stress: an investigation of the 2010 Canadian Community Health Survey. J Occup Health Psychol 18(2):191–197. doi:10.1037/a0031806

Taylor MK, Pietrobon R, Taverniers J, Leon MR, Fern BJ (2013) Relationships of hardiness to physical and mental health status in military men: a test of mediated effects. J Behav Med 36(1):1–9

Virtanen M, Vahtera J, Pentti J, Honkonen T, Elovainio M, Kivimäki M (2007) Job strain and psychologic distress: influence on sickness absence among Finnish employees. Am J Prev Med 33(3):182–187. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.05.003

Wang J (2005) Work stress as a risk factor for major depressive episode(s). Psychol Med J Res Psychiatry Allied Sci 35(6):865–871. doi:10.1017/S0033291704003241

Wang J, Patten SB (2001) Perceived work stress and major depression in the Canadian employed population, 20–49 years old. J Occup Health Psychol 6(4):283–289. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.6.4.283

Warttig SL, Forshaw MJ, South J, White AK (2013) New, normative, English-sample data for the Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4). J Health Psychol 18(12):1617–1628

Acknowledgments

We wish to extend our gratitude to the Shell employees who gave their time to participate in this study.

Conflict of interest

While the original study reported here was not funded, one of the authors (JMV) has subsequently received a PhD studentship from Shell, while AF, RS, KL and HdB are employees of Shell. The first and senior authors ND and MML have received no financial or any other kind of benefit for the research reported in this paper.

Ethical standard

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Information provided to participants at beginning of online survey

-

Resilience Survey

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. This questionnaire is part of a study being conducted by Shell Health and Trinity College Dublin into the Resilience Programme.

Participation in this study is voluntary, and you are free to withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. Data will be used for research purposes only. All information will be treated confidentially, and your identification cannot be known. If you have any questions or if you would like to discuss the study in further detail, you may contact me or my supervisors using the details below

Researcher

[Primary researcher’s contact details provided]

Supervisor

[Academic supervisor’s contact details provided]

Appendix 2: Information provided to participants at end of online survey

-

Resilience Survey

Thank you for taking part in this research. The study you just participated in is investigating resilience and quality of life amongst maritime crew members.

All data collected will be treated anonymously. Your name cannot be linked with any results at any stage. In accordance with the Freedom of Information Act (1977), you have the right to access your data and the study’s results at any time on request.

If you have any questions or comments regarding this study, do not hesitate to email us. You can contact me or my supervisors using the contact details below. You can also contact [contact details within shipping company provided]. Thank you once again for your participation

Researcher

[Primary researcher’s contact details provided]

Supervisor within University

[Academic supervisor’s contact details provided]

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doyle, N., MacLachlan, M., Fraser, A. et al. Resilience and well-being amongst seafarers: cross-sectional study of crew across 51 ships. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 89, 199–209 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-015-1063-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-015-1063-9