Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study is to evaluate the frequency and characteristics of facial involvement in inclusion body myositis (IBM) patients and to compare it to the one previously described in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSHD) patients.

Methods

Thirty-two IBM patients were included and compared to 29 controls and 39 FSHD patients. All participants were recorded in a video as they performed a series of seven facial tasks. Five raters independently assessed facial weakness using both a qualitative evaluation and a semi-quantitative facial weakness score (FWS).

Results

IBM patients had higher FWS than controls (7.89 ± 7.56 vs 1.06 ± 0.88, p < 0.001). Twenty IBM patients (63%) had a facial weakness with a FWS above the maximum value for controls. All facial tasks were significantly more impaired in IBM patients compared to controls (p < 0.001), task 2 evaluating orbiculari oculi muscle weakness being the most affected. IBM patients with facial weakness reported more swallowing troubles than IBM patients without facial weakness (p = 0.03). FSHD patients displayed higher FWS than IBM patients (12.16 ± 8.37 vs 7.89 ± 7.56, p = 0.01) with more pronounced facial asymmetry (p = 0.01). FWS inter-rater ICC was 0.775.

Conclusion

This study enabled us to estimate the frequency of facial impairment in IBM in more than half of patients, to detail its characteristics and to compare them with those of FSHD patients. The standardized, semi-quantitative FWS is an interesting diagnostic help in IBM as it appeared more sensitive than qualitative evaluation to detect mild facial weakness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sporadic inclusion body myositis (IBM) is the most frequent acquired myopathy presenting over the age of 50 years [1]. The disease course is slowly progressive and muscle weakness is frequently asymmetric and highly selective with prominent involvement of quadriceps and flexor digitorum profundus [2]. IBM diagnosis has evolved with time: while the presence of canonical pathological features was initially emphasized, the importance and specificity of clinical criteria has been more recently put forth [3,4,5].

In the diagnosis process of muscular diseases, the presence of a facial weakness can be a key feature for diagnosis since there are very few myopathies affecting the face in adulthood. Among them, some myopathies have a highly suggestive facial involvement pattern such as myotonic dystrophy type 1 [6], oculopharyngeal muscle dystrophy [7] or facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) [8].

In IBM patients, mild to moderate facial weakness is frequently described, but the frequency varies greatly in previous cohorts, ranging from 41 to 66% [9, 10]. Orbicularis oculi muscle is described as the most commonly affected muscle, with no detailed information regarding the severity of facial weakness or its association with other phenotypic features [10]. In particular, while IBM patients often develop dysphagia due to the involvement of oropharyngeal muscles, the presence of facial involvement has not been correlated to swallowing troubles or clinical prognosis in such patients.

Facial muscles analysis is challenging in patients with myopathies due to the absence of dedicated scales to monitor them. Validated facial clinical scores, used in other diseases, in particular for peripheral facial paralysis [11], do not apply well to myopathies, where the selective character of muscle impairment and the slow progression rate make their application inappropriate. Among muscular diseases, FSHD is one of the most frequent myopathies affecting the face in adulthood [12,13,14] and has been the subject of the few studies analyzing facial muscles.

A new Facial Weakness Score (FWS) has been recently proposed to assess facial weakness in a population of FSHD patients [15], using a short video recorded during the clinical examination. Semi quantitative analysis based on video assessment is an innovative tool that allows reproducible scoring of facial weakness. Its clinical application in various myopathies is now needed to assess its usefulness in such diseases.

Therefore, the objective of this study is: (i) to evaluate the frequency and characteristics of facial involvement in IBM using a semi quantitative facial score and (ii) to compare this facial involvement to the one previously described in FSHD patients.

Patients and methods

Patients

Participants were prospectively and consecutively included in this study between February 2022 and February 2023: 32 IBM and 39 FSHD patients, followed in the Referral Center for Neuromuscular Diseases and ALS (University Hospital La Timone, Marseille). These patients were compared to 29 healthy controls volunteers, without any neurological pathology or facial involvement, included at the same period. They were generally healthcare professionals or patient attendants.

-

Inclusion criteria:

IBM patients had all performed a muscle biopsy consistent with the diagnosis of IBM and all met Lloyd’s criteria [16].

FSHD patients were all genetically confirmed by molecular combing technique [17] and presented a contracted 4qA allele with an estimated size of less than 40 kb (i.e., 10 RU or less).

-

Exclusion criteria:

All participants with a condition likely to affect facial muscles (such as stroke, facial paralysis, etc.) were excluded from this study. All patients were older than 18 years.

Data collection

Demographic data included age, sex, BMI, date of diagnosis, disease duration and age at first symptoms, initial clinical presentation, presence of dysphagia and personal medical history, creatinine phospho-kinase serum level (CK) at evaluation, number of D4Z4 repeat units (RUs) in molecular analysis for FSHD patients and the histopathological features in IBM patients.

Severity of the disease was assessed by validated specific clinical scores for each disease:

-

Inclusion body myositis functional rating scale (IBM-FRS) [18] and the sporadic IBM weakness composite index (IWCI) [19] scales for IBM.

-

Clinical severity scale (CSS) [20] and FSHD score [21] for FSHD patients.

During the evaluation, FSHD and IBM patients were asked to fill in two self-assessed questionnaires:

-

The Facial Clinical Evaluation Instrumental Scale, "FaCE" [22]: a self-reported questionnaire used by otorhinolaryngologists and developed to quantify social disability and psychological impact in patients with peripheral facial paralysis.

-

The Swallowing Assessment Scale, “SWAL-QOL” [23]: a self-reported questionnaire designed to assess the impact of swallowing disorders through the collection of symptoms that have occurred in the past month.

Video recording of facial muscles

As detailed by Loonen et al. in their study [15], all participants were recorded during a 45-s video as they performed a series of facial movements. The patients were instructed by the examiner to perform the following sequence: “Close the eyes gently”, “Close the eyes as hard as possible”, “Raise your eyebrows”, “Frown your eyebrows”, “Make a kiss”, “Smile big and show teeth”, “Puff up your cheeks”. In addition to the original study, and to allow a qualitative assessment as faithful as possible to a standard clinical examination at the patient’s bedside, all participants were asked to perform an eighth task consisting of repeating a sentence (“Il fait beau à Marseille”), to embrace a dynamic view of the face. This eight task was not part of the FWS score. The videos were shot using a camera positioned in a standardized position, 50 cm from the patient's face (UHD resolution—4 K (3840 × 2160) 30 fps).

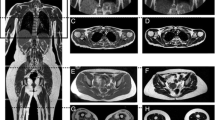

Examples of facial tasks in IBM patients are displayed in Fig. 1.

Facial involvement scoring

The videos of each participant (patients and controls mixed) were then independently viewed in random order by five raters (AV, ECS, ED, EF and LK) blinded to the diagnosis of each subject. The raters were all neurologists from the neuromuscular reference center of Marseille, with several years of expertise in neuromuscular diseases.

Two types of evaluation were performed successively:

-

(1)

Qualitative assessment: Each rater had to make a binary evaluation regarding the presence or absence of pathological facial weakness, without using the specific rating scale (see below). Qualitative analysis was based on the raters’ qualitative assessment of pathological facial impairment during the first video analysis (without using the FWS). The presence of facial impairment in a patient was considered “definite” when it was noted by at least 4 out of 5 raters.

-

(2)

Semi-quantitative evaluation: The raters then assessed the seven facial tasks on both sides (left and right) using a dedicated semi-quantitative 4-point scale (0 = no impairment on the task, 1 = mild impairment, 2 = moderate impairment, 3 = severe impairment). To minimize the inter-rater variability, a scoring guide was developed by two raters (EF and ECS) (supplementary data). The maximum score per rater was, therefore, of 21 for each side of the face (42 in total). A final total score, referred to the Facial Weakness Score (FWS) was calculated, by meaning the score of all raters.

Sub-analyses of the FWS included assessment of the upper or lower parts of the face: FWSUP subscore (the first four tasks) and FWSLP subscore (the last three tasks). The asymmetry score corresponded to the sum of the right-left differences of each task (in absolute values).

Reproducibility of FWS

-

Intra-rater: The intra-rater reproducibility of the test was studied in an independent test performed prior to scoring, on a sample of five randomly selected patient videos, by asking each rater to score them twice at a 7-day interval.

The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) ranged from 0.71 (rater 4) to 0.97 (rater 3).

-

Inter-rater: The final inter-rater reproducibility (inter-rater ICC) was analyzed at the end of the study from the FWS of the 100 subjects and showed an inter-rater ICC of 0.775.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were expressed in mean (standard deviation) and compared using the Student’s T-test or the one-way ANOVA test corrected by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. ICC was calculated for intra- and inter-rater reproducibility using a Cronbach’s Alpha test (2-factor random, absolute consistency). Statistical analysis, Pearson correlation, linear regression and graph constructions were performed using Graph Pad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and IBM SPSS statistics, version 20 (IBM SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States). A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Population

Thirty-two IBM patients were included in the study and compared to 29 healthy controls and 39 FSHD patients. The characteristics of the three groups are presented in Table 1. IBM patients were older than controls (72.1 ± 8 vs 60.1 ± 14, p < 0.003) and FSHD patients (72.1 ± 8 vs 53.7 ± 16, p < 0.001). As expected, the age of onset was significantly lower in FSHD patients (30.4 ± 19.7, vs. 61.5 ± 9.3, p < 0.001) as well as the duration of the disease was significantly longer in FSHD patients (23.7 ± 15.2 vs. 10.5 ± 6.5, p = 0.002). Twenty-four IBM patients reported swallowing troubles whereas none of the FSHD patient complained about dysphagia (p < 0.001). Only one IBM patient presented with facial onset symptoms, compared to 9 FSHD patients (p < 0.001).

Facial involvement in IBM patients

IBM patients had higher FWS than controls (7.89 ± 7.56 vs 1.06 ± 0.88, p < 0.001). FWS ranged from 0.6 to 33.8 in IBM patients whereas FWS ranged from 0 to 3.4 in healthy controls. The upper limit of FWS for controls was 3.4 (Fig. 2). The estimated frequency of facial involvement in our IBM cohort, defined here as a FWS above the maximum value for controls, was 20 out of 32 IBM patients (63%). IBM patients had higher scores compared to controls for all tasks (p < 0.001), with the highest scores for task 2 (“Close the eyes as hard as possible”) (1.74 ± 1.57 vs 0.23 ± 0.33 (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Facial Weakness in IBM patients. Scatter plots showing facial impairment in IBM patients compared to healthy controls (HC) using the semi-quantitative Facial Weakness Score: Total Facial weakness score (FWS) (a), Facial Weakness Score Upper part of the face (FWSUP) (b), Facial Weakness Score Lower part of the face (FWSLP) (c). Thick bar represents the mean FWS in each group. The arrow represents the maximum FWS value in HC, above which the facial weakness was considered significant in IBM patients

In IBM patients, FWS was not correlated with IBMFRS (p = 0.212) and IWCI (p = 0.102), but it was inversely correlated with the SWAL-QOL questionnaire scores (rho = – 0.664, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3a). FWS was not correlated with age (p = 0.439), duration of disease (p = 0.632) and age of onset (p = 0.582).

Clinical significance of facial weakness in IBM patients. a There was a significant correlation between Swal-Qol scores and FWS (rho = – 0.664, p < 0.001) and FWSLP (rho = – 0.661, p < 0.001). b IBM patients with facial weakness presented with a lower Swal-Qol scores (p = 0.0322) than IBM patients with no facial impairment. Abbreviations: FWS Facial Weakness score, FWSUP facial weakness score upper part, FWS facial weakness score lower part, score IBM Inclusion Body myositis

When comparing the subgroup of IBM patients with (20/32 patients) and without facial weakness (12/32), the SWAL-QOL questionnaire scores were significantly lower in the first group (p = 0.03) (Fig. 3b).

Facial involvement of IBM patients compared to FSHD patients (Table 2 and Fig. 4).

Comparison of facial impairment between IBM and FSHD patients. Bar charts representing the mean Facial Weakness Score (FWS) of each task for IBM and FSHD patients. Task 2 was the only task with higher impairment in IBM patients compared to FSHD patients. *Indicates significant difference between the two groups, with higher mean FWS in FSHD patients compared to IBM patients for Task 5 (p < 0.001), Task 6 (p = 0.043) and Task 7 (p < 0.001)

FSHD patients had a more severe facial involvement with higher FWS than IBM patients (12.16 ± 8.37 vs 7.89 ± 7.56, p = 0.01) (Fig. 4). FWS ranged from 0.6 to 35.8 in FSHD patients. The estimated frequency of facial involvement in FSHD patients (FWS above the maximum value for controls), was 34 out of 39 (87%).

FSWUP showed no significant difference between the two groups of patients (p = 0.598) while FSWLP was significantly higher in FSHD patients (5.93 ± 4.11 vs 2.49 ± 3.01 p < 0.001). Three tasks (task 5, task 6 and task 7) were the ones that were significantly different between IBM and FSHD patients with a significantly greater impairment in FSHD patients, respectively 2.16 ± 1.61 vs 0.73 ± 1.20 (p < 0.001), 1.43 ± 1.15 vs 1.06 ± 1.18 (p < 0.001), and 2.34 ± 1.71 vs 0.69 ± 0.96 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). The asymmetry score was significantly greater in FSHD patients than in IBM patients (2.23 ± 1.41 vs 0.93 ± 0.86, p < 0.001).

Concerning the self-questionnaires, IBM patients had a greater complaint of swallowing disorders than FSHD patients, with a significant difference on the SWAL-QOL questionnaire scores (156 ± 38 vs 220 ± 0, p = 0.002). There was no significant difference in the perception of facial impairment on the "FaCE" self-questionnaire scores between FSHD and IBM patients (66 ± 8 vs 71 ± 8, p = 0.160).

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative analysis results were compared with the semi-quantitative analysis using the FWS, where pathological facial involvement was retained for patients with FWS > 3.4 (maximum FWS value in controls).

Among FSHD patients, 34 of 39 patients had FWS > 3.4 and were therefore considered to have pathological facial involvement according to the semi-quantitative assessment. Among these 34 patients, 28 (82%) had been considered to have pathological facial involvement according to the qualitative analysis and 6 (18%) had clinical uncertainty (less than 4 raters in agreement).

In IBM patients, our population included 20 patients with facial weakness based on FWS results. Among these 20 patients, only 11 were considered to have a facial weakness according to the qualitative analysis (55%). Mean FWS in these 11 IBM patients was higher than FWS in the 9 remaining uncertain patients: 13.46 ± 3.14 vs 6.04 ± 2.86 (p < 0.001).

Discussion

In a cross-sectional study with prospective recruitment, a semi-quantitative FWS was used to estimate the frequency of facial muscle weakness in IBM. In our population, this frequency was around 63%, which corresponds to the upper range of the literature. To our knowledge, the description of facial involvement in IBM had never been the subject of a dedicated study, but it had been estimated in large retrospective studies of cohorts of IBM patients, ranging from 40% [10], 43% [24], 53% [25] and up to 66% [26].

Our work has detailed the clinical features of this facial impairment through the use of several specific tasks performed during clinical examination and recorded during a short video. In previous descriptions, the facial weakness seemed to predominate in the orbicularis oculi muscles [10, 24], which is also the case in our study, where task number 2 (“Close the eyes as hard as possible”) was the most affected. While the weakness was more pronounced on the upper part of the face, it should be remembered that all facial tasks were significantly more affected in IBM patients than in controls. This highlights the presence of a facial weakness on both upper and lower parts of the face in IBM (which had not been frequently reported in the literature). In retrospective studies of IBM patients, clinical examination was not focused on facial muscle testing, which precludes further comparison with our results. In a 12-year natural history study of 64 IBM patients, a mean decline in strength of 3.5 and 5.4% per year according to the manual muscle testing and quantitative muscle testing was observed but the presence and/or the progression of facial involvement were not directly assessed [27]. In a cross-sectional study of 57 biopsy-proven IBM cases from Australian centers, the manual muscle testing has included the assessment of orbicularis oris and orbicularis oculi. According to MRC score, the weakness of both muscles was frequent but mild, at 4 for most of the patients [28].

Presentations with severe facial involvement have been previously described in IBM in few case reports [29, 30]. In our study, only one IBM patient presented with facial onset weakness. This 68-year-old female patient presented at the age of 54 with facial diplegia followed by a progressive proximal motor deficit of the lower limbs, in a context of mild CK elevation. The diagnosis was made 10 years after symptoms onset. Muscle biopsy showed a pattern typical of IBM. She also presented severe swallowing disorders.

Interestingly, in IBM patients, the FWS was correlated to the SWAL-QOL questionnaire suggesting that facial weakness is more pronounced in patients with swallowing impairment. These results may suggest a correlation between facial weakness and the presence of swallowing disorders in IBM patients, but this tendency need to be confirmed through a study focused on dysphagia in IBM patients [31]. Noteworthy, the FWS did not correlate to the severity scores (IBM-FRS and IWCI) suggesting that facial weakness was independent of the overall weakness.

Our work has highlighted the differences in facial muscle involvement between IBM and FSHD patients. In our study, the frequency of facial involvement in FSHD patients was estimated around 87%. This is in line with the literature [32,33,34] as "facial sparing" phenotypes are reported in approximately 10% of FSHD patients [35,36,37]. FSHD patients in our study had a higher FWS than IBM patients, suggesting a more severe facial weakness. Lower facial compartment weakness was more pronounced in FSHD patients, with particularly severe impairment in tasks 5, 6 and 7, corresponding to weakness of the orbicularis oris and buccinator muscles. The asymmetry score was also significantly more pronounced in FSHD patients.

Our results in FSHD patients can be compared to the study conducted by Loonen et al. [15], who explored facial impairment in this myopathy. To be as comparable as possible with this previous study, we applied the same video analysis technique with the seven identical tasks. In this work, the estimated frequency of facial impairment in FSHD patients was around 54%. This difference with our study may be explained by the very high maximal FWS in the healthy controls group reported by Loonen and colleagues [15], which may have understated the frequency of facial weakness in FSHD patients.

Estimating the frequency of facial weakness in myopathies is challenging by the absence of a dedicated scale and the lack of a “gold standard”. To better understand the interest of using a semi-quantitative score for facial movement analysis, we compared it with a qualitative analysis as a “real life assessment”, by adding an eighth task analyzing the dynamic aspect of facial muscles. Our study suggests that FWS is more sensitive than qualitative assessment when the facial weakness is discrete. In fact, in half of IBM patients, there was a discrepancy between practitioners regarding the presence of pathological facial impairment, whereas in FSHD patients, where facial weakness was more severe, clinical consensus was easier. The FWS intra- and inter-rater reproducibility in our study makes it a valid assessment tool. One of the major advantages of this score is its ease of use, which can be simply implemented in routine clinical practice at the patient’s bedside.

Patients may have a different perception of facial weakness than physicians, especially when they have facial weakness for a long time. In our study, we made an attempt to assess the perception of facial weakness by the patient itself using the self-administered “FaCE” questionnaire. The results between IBM and FSHD patients were not significantly different, which could be explained by the sampling effect and by the self-questionnaire used here, as this scale was developed for a frigore facial paralysis and not for patients with myopathies. However, it can also be hypothesized that patients with FSHD have an early onset of facial involvement and may be less prone to report their facial symptoms even though they are more severe than those of IBM patients. A new patient-reported scale has been recently developed in FSHD patients to address this issue [38].

The limitations of our work include its monocentric nature and the intrinsic limits of video testing, where scoring depends on patient participation and rater judgment.

In conclusion, this study enabled us to estimate the frequency of facial impairment in IBM which was found in more than a half of the patients. Facial weakness in IBM is more pronounced in the upper part of the face compared to the facial weakness in FSHD patients, which is more severe, more pronounced in lower part of the face and more asymmetrical. The use of a standardized, semi-quantitative facial score allows clinician to detect mild facial weakness and provide an important diagnostic help in IBM. This is relevant as facial weakness in IBM seems to correlate with the presence of oropharyngeal involvement and swallowing disorders.

References

Greenberg SA (2019) Inclusion body myositis: clinical features and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 15(5):257–272. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-019-0186-x

Naddaf E, Barohn RJ, Dimachkie MM (2018) Inclusion body myositis: update on pathogenesis and treatment. Neurotherapeutics 15(4):995–1005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-018-0658-8

Goyal NA (2022) Inclusion body myositis. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 28(6):1663–1677. https://doi.org/10.1212/CON.0000000000001204

Benveniste O, Stenzel W, Hilton-Jones D, Sandri M, Boyer O, van Engelen BG (2015) Amyloid deposits and inflammatory infiltrates in sporadic inclusion body myositis: the inflammatory egg comes before the degenerative chicken. Acta Neuropathol 129(5):611–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1384-5

Rose MR, ENMC IBM Working Group (2013) 188th ENMC International Workshop: Inclusion Body Myositis, 2–4 December 2011 Naarden The Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord. 23(12):1044–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2013.08.007

Thornton CA (2014) Myotonic dystrophy. Neurol Clin. 32(3):705–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2014.04.011

Yamashita S (2021) Recent progress in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. J Clin Med 10(7):1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10071375

Mul K (2022) Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 28(6):1735–1751. https://doi.org/10.1212/CON.0000000000001155

Dimachkie MM, Barohn RJ (2013) Inclusion body myositis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13(1):321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-012-0321-4

Badrising UA, Maat-Schieman ML, van Houwelingen JC, van Doorn PA, van Duinen SG, van Engelen BG, Faber CG, Hoogendijk JE, de Jager AE, Koehler PJ, de Visser M, Verschuuren JJ, Wintzen AR (2005) Inclusion body myositis. Clinical features and clinical course of the disease in 64 patients. J Neurol. 252(12):1448–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-005-0884-y

Fattah AY, Gurusinghe ADR, Gavilan J, Hadlock TA, Marcus JR, Marres H, Nduka CC, Slattery WH, Snyder-Warwick AK, Sir Charles Bell Society (2015) Facial nerve grading instruments: systematic review of the literature and suggestion for uniformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 135(2):569–579. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000000905

He JJ, Lin XD, Lin F, Xu GR, Xu LQ, Hu W, Wang DN, Lin HX, Lin MT, Wang N, Wang ZQ (2018) Clinical and genetic features of patients with facial-sparing facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Eur J Neurol. 25(2):356–364

Mul K, Lassche S, Voermans NC, Padberg GW, Horlings CG, van Engelen BG (2016) What’s in a name? The clinical features of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Pract Neurol 16(3):201–207. https://doi.org/10.1136/practneurol-2015-001353

Tawil R, Van Der Maarel SM (2006) Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 34(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.20522

Loonen TGJ, Horlings CGC, Vincenten SCC, Beurskens CHG, Knuijt S, Padberg GWAM, Statland JM, Voermans NC, Maal TJJ, van Engelen BGM, Mul K (2021) Characterizing the face in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. J Neurol. 268(4):1342–1350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10281-z

Lloyd TE, Mammen AL, Amato AA et al (2014) Evaluation and construction of diagnostic criteria for inclusion body myositis. Neurology. 83(5):426–433

Nguyen K, Walrafen P, Bernard R, Attarian S, Chaix C, Vovan C, Renard E, Dufrane N, Pouget J, Vannier A, Bensimon A (2011) Lévy N Molecular combing reveals allelic combinations in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 70(4):627–33

Jackson CE, Barohn RJ, Gronseth G, Pandya S, Herbelin L, Muscle Study Group (2008) Inclusion body myositis functional rating scale: a reliable and valid measure of disease severity. Muscle Nerve. 37(4):473–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.20958

Olivier Benveniste and others (2011) Long-term observational study of sporadic inclusion body myositis. Brain 134(11):3176–3184. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr21317

Ricci G, Ruggiero L, Vercelli L, Sera F, Nikolic A, Govi M, Mele F, Daolio J, Angelini C, Antonini G, Berardinelli A, Bucci E, Cao M, D’Amico MC, D’Angelo G, Di Muzio A, Filosto M, Maggi L, Moggio M, Mongini T, Morandi L, Pegoraro E, Rodolico C, Santoro L, Siciliano G, Tomelleri G, Villa L, Tupler R (2016) A novel clinical tool to classify facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy phenotypes. J Neurol. 263(6):1204–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-016-8123-2

Lamperti C, Fabbri G, Vercelli L, D’Amico R, Frusciante R, Bonifazi E, Fiorillo C, Borsato C, Cao M, Servida M, Greco F, Di Leo R, Volpi L, Manzoli C, Cudia P, Pastorello E, Ricciardi L, Siciliano G, Galluzzi G, Rodolico C, Santoro L, Tomelleri G, Angelini C, Ricci E, Palmucci L, Moggio M, Tupler R (2010) A standardized clinical evaluation of patients affected by facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: The FSHD clinical score. Muscle Nerve 42(2):213–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.21671

Amélie Faure, Natacha Paillet (2020) Étude de la qualité de vie des patients paralysés faciaux. Sciences du Vivant [q-bio]

Khaldoun E, Woisard V, Verin E (2009) Validation in French of the SWAL-QOL scale in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 33(3):167–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gcb.2008.12.012

Felice KJ, North WA (2001) Inclusion body myositis in Connecticut: observations in 35 patients during an 8-year period. Medicine (Baltimore) 80(5):320–327. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005792-200109000-00006

Ringel SP, Kenny CE, Neville HE, Giorno R, Carry MR (1987) Spectrum of inclusion body myositis. Arch Neurol 44(11):1154–1157. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1987.00520230042011

Amato AA, Gronseth GS, Jackson CE, Wolfe GI, Katz JS, Bryan WW, Barohn RJ (1996) Inclusion body myositis: clinical and pathological boundaries. Ann Neurol 40(4):581–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410400407

Cox FM, Titulaer MJ, Sont JK, Wintzen AR, Verschuuren JJ, Badrising UA (2011) A 12-year follow-up in sporadic inclusion body myositis: an end stage with major disabilities. Brain 134(Pt 11):3167–3175. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr217

Needham M, James I, Corbett A, Day T, Christiansen F, Phillips B, Mastaglia FL (2008) Sporadic inclusion body myositis: phenotypic variability and influence of HLA-DR3 in a cohort of 57 Australian cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79(9):1056–1060. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2007.138891

Ghosh PS, Laughlin RS, Engel AG (2014) Inclusion-body myositis presenting with facial diplegia. Muscle Nerve 49(2):287–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.24060

Cummins G, O’Donovan D, Molyneux A, Stacpoole S (2019) Facial diplegia as the presenting symptom of inclusion body myositis. Muscle Nerve 60(2):E14–E16. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26514

Ambrocio KR, Garand KLF, Roy B, Bhutada AM, Malandraki GA (2023) Diagnosing and managing dysphagia in inclusion body myositis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kead194

Hassan A, Jones LK Jr, Milone M, Kumar N (2012) Focal and other unusual presentations of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 46(3):421–425. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.23358

Mostacciuolo ML, Pastorello E, Vazza G, Miorin M, Angelini C, Tomelleri G, Galluzzi G, Trevisan CP (2009) Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: epidemiological and molecular study in a north-east Italian population sample. Clin Genet 75(6):550–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01158.x

Statland JM, Tawil R (2016) Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 22(6, Muscle and Neuromuscular Junction Disorders):1916–1931. https://doi.org/10.1212/CON.0000000000000399

Pastorello E, Cao M, Trevisan CP (2012) Atypical onset in a series of 122 cases with FacioScapuloHumeral muscular dystrophy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 114(3):230–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.10.022

Attarian S, Salort-Campana E, Nguyen K, Behin A, Andoni UJ (2012) Recommendations for the management of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy in 2011. Rev Neurol (Paris) 168(12):910–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2011.11.008

Preston MK, Tawil R, Wang LH (1999) Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy. [updated 2020 Feb 6]. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2022

Mul K, Wijayanto F, Loonen TGJ, Groot P, Vincenten SCC, Knuijt S, Groothuis JT, Maal TJJ, Heskes T, Voermans NC, Engelen BGMV (2023) Development and validation of the patient-reported “Facial Function Scale” for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Disabil Rehabil 45(9):1530–1535. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2066208

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of La Timone (reference RGPD 2019–01 PADS22-38) and conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

informed consent

All participants signed informed consent.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fortanier, E., Delmont, E., Kouton, L. et al. Face to Face: deciphering facial involvement in inclusion body myositis. J Neurol 271, 410–418 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-11986-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-11986-7