Abstract

Objective

To describe the course of disability in patients with benign multiple sclerosis—i.e., with an expanded disability status scale score < 3 10 years after disease onset—for up to 30 years after disease onset. We evaluated the proportion of patients remaining in the benign state on the long term and the factor associated with this favorable outcome and determined the pattern of disability course after the loss of the benign status.

Methods

Patients were selected from the ReLSEP, a French population-based registry. We studied the probability (Kaplan–Meier method) and predictors (multivariate Cox model) of remaining < 3 after year 10, and the course of disability after score 3 according to the duration of the benign phase in patients with ≥ 30 years of follow-up (graphs of the course of the mean expanded disability status scale scores in subgroups of patients).

Results

2295/3440 patients had benign multiple sclerosis (66.7%). The probability of remaining benign at year 30 was 0.26 (95% CI 0.26–0.32). A young age at disease onset and a good recovery after the first relapse were associated with remaining benign. Graphs illustrate that those who lost their benign status between years 10 and 30 follow a two-stage course. Beyond score 3, disability accumulation is similar in all but lower disability scores at advanced age are associated with longer benign periods.

Conclusion

The longer a patient remains in the benign state, the lower the final EDSS at advanced age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Disability worsening is the main issue in multiple sclerosis (MS) [1, 2], and is usually evaluated by the expanded disability status scale (EDSS) [3]. This worsening seems to follow a “two-stage model” [4,5,6]. The time to reach the pivotal score of EDSS 3 from disease onset (DO) varies widely [5]. Afterwards, most patients will endure a slow but irreversible worsening of disability toward higher EDSS scores, this stage being largely independent of the first one. Patients’ age at the highest irreversible EDSS score seems to be remarkably similar [7], while some have low levels of disability at an advanced age [8,9,10].

Patients with a long-lasting low level of disability have been identified as having “benign multiple sclerosis”. This term is usually defined by an EDSS score < 3 or 4 at least 10 years after DO. However, as stated above, disease course when patients are no longer benign could be independent of the initial benign phase [11]. In other words, a long benign phase could not necessarily result in low disability at advanced age.

We aimed to study the long-term worsening of the irreversible EDSS score in patients with relapsing–remitting onset MS with an EDSS score < 3 at year 10 after DO. We first focused on the benign phase, looking for factors associated with the probability of remaining benign in the long term. Then, we wanted to characterize disability progression in the long term once EDSS 3 had been reached. To this purpose, we focused on patients with benign MS and at least 30 years of follow-up.

Materials and methods

Study population

Patients were identified through the Registre lorrain des scléroses en plaques (ReLSEP), an exhaustive population-based registry of patients with MS in North-Eastern France. This registry was initiated in 1996 in Lorraine, France, and is compiled of data from multiple sources: private practice and hospital neurologists, CSF biochemical analysis laboratories, the French Hospital Information System and the Health Insurance System database [12]. More than 90% of all patients with MS in Lorraine were registered in the ReLSEP in 2008 and this proportion has increased since with the multiplication of sources [13]. Today, all patients living in Lorraine with disease onset after 1996 are registered in the ReLSEP and prospectively followed up. Data from prevalent cases in 1996 were also collected (retrospectively and prospectively). Data were anonymized and entered into the European Database for Multiple Sclerosis (EDMUS) system [14].

The cohort for this study comprised all patients with relapsing–remitting onset MS and at least 10 years of follow-up (complete cohort C10). In this cohort, we identified patients with benign MS which was defined as having an irreversible EDSS < 3 at year 10 after DO (cohort B10). C10 and B10 were used for survival analysis. Using the same registry, we also created a cohort of patients with relapsing–remitting onset MS and at least 30 years of follow-up to be able to describe disease course once the benign phase is over (complete cohort C30). Among these patients, those with an irreversible EDSS < 3 at year 10 (and at least 30 years of follow-up) formed a B30 cohort. C10 overlaps with C30, and B10 with B30.

The irreversible EDSS scores correspond to the EDMUS impairment scale adapted from the disability status scale (EIS-DSS), an estimation of the irreversible EDSS score (with integer values from 0 to 10). For simplification reasons, the term “EDSS” is used throughout [14]. Then, when we refer to an EDSS score < 3, it means that the EIS-DSS could be 0; 1 or 2 included.

Patients might have been treated by disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) during their follow-up, either during the benign phase or later.

Data were extracted in February 2019.

Description and analysis of the benign phase

We first used data from B10 and determined median survival time to the first EDSS ≥ 3 from year 10 using the Kaplan–Meier method.

To account for the possibility of informative censoring during follow-up, we recorded two reasons for the end of follow-up: information at the latest follow-up possible given the date of extraction, or before that for patients lost to follow-up (dropouts) or deceased.

We used a bivariate Cox model to test associations between the outcome variable in patients from the B10 cohort, i.e. EDSS ≥ 3 after year 10, and some variables known to influence the long-term course of MS: sex, age at DO, number of relapses during the first 5 years after DO, EDSS score 6 months after the first relapse, time between the first two relapses, and treatment by any DMT for more than 3 months. The two last covariates were coded as time-dependent. If bivariate associations were significant at the level p = 0.02, covariates were used in the multivariate model. Log-linearity of effect over time and the proportional hazards hypothesis were checked. In case of violation of the second hypothesis, an interaction with time was used. Statistical results were considered significant if p < 0.05.

Description of EDSS course after the end of the benign phase

Data were extracted from C30 to form six groups according to the “benign” and “non-benign” status of patients at different time points. The first group consisted of patients who were non-benign at year 10 (EDSS ≥ 3 before year 10). The other groups described patients who had benefited from a benign status: the second group included patients with benign MS at year 10 whose EDSS score increased beyond 3 between years 10 and 15; the third between years 15 and 20; the fourth between years 20 and year 25; the fifth between years 25 and 30; and finally, the sixth group was made of patients with an EDSS < 3 at year 30 (i.e. still benign after 30 years of MS). Two graphs were used to describe the groups’ EDSS course. The first one illustrates the mean EDSS scores (and standard deviation SD) of each group at different time points from DO (DO, year 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30). The second one gives the mean EDSS (and SD) of each group at different ages (every 5 years from age 20 to 70).

The data analysis for this work was made with R software v.3.6.1 (R Core Team 2019).

Results

Description and analysis of the benign phase

A total of 3440 patients had relapsing–remitting onset MS and a disease duration of at least 10 years (C10). The median age at disease onset was 30 (interquartile range IQR 14) and 2521 patients were female (73.3%). We identified 2295 patients with benign MS at year 10 (B10, 66.7% of C10). Their demographic and clinical characteristics are given in Table 1. The median follow-up of B10 was 22 years from DO (IQR 13).

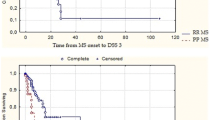

In B10, the median survival time from DO to the first EDSS score ≥ 3 was 22.6 years (95% confidence interval 95% CI 21.9–23.6) (Fig. 1). The first and third quartile survival times were, respectively, 15.5 years (95% CI 15.1–16.0) and 32.7 years (95% CI 31.0–35.0). The probability of remaining benign at year 30 was 0.26 (95% CI 0.26–0.32).

The reasons for the end of follow-up before each 5-year time point after year 10 in B10 are described in Fig. 2. Among the patients with last information between years 10 and 30, fewer than 12% were dropouts, the remaining patients were censored because they reached their latest follow-up possible.

Flow chart from year 10 to year 30 after disease onset. Legend: 2295 patients with benign multiple sclerosis (relapsing–remitting onset, EDSS < 3 at year 10), each 5-year time point from year 10 until year 30. Censored patients before each time point are classified by longest follow-up or loss to follow-up. EDSS: expanded disability status scale

In the multivariate Cox model (cohort B10), an older age at DO, being treated with a DMT at any time before the outcome, and a higher EDSS after the first relapse were associated with reaching an EDSS score ≥ 3 during follow-up (Table 2).

Description of EDSS course after the end of the benign phase

We identified 738 patients in the C30 cohort, i.e. with relapsing–remitting onset MS and at least 30 years of follow-up. The median age at DO was 25 years (IQR 11) with 560 female patients (75.9%). Among them, 562 patients had an EDSS score ≥ 3 at year 10 (B30) with a median follow-up of 37 years from DO (IQR 10) (Table 1).

The mean EDSS scores at different time points for the six groups of patients in the C30 cohort are described with time from DO on the X-axis in Fig. 3 and with age on the X-axis in Fig. 4.

Progression of the mean EDSS scores over 30 years after disease onset. Legend: Progression of the mean EDSS in six groups of patients with relapsing–remitting onset multiple sclerosis and at least 30 years of follow-up (total of 738 patients). Group 1: patients with EDSS ≥ 3 at year 10 after disease onset (“never benign”). Groups 2 to 5: patients with benign multiple sclerosis (EDSS < 3 at year 10) but with EDSS worsening over 3 between different time points: years 10–15 (group 2), 15–20 (group 3), 20–15 (group 4) and 25–30 (group 5). Group 6: patients with EDSS < 3 at year 30 (“still benign” at the end of the study). EDSS: expanded disability status scale; SD: standard deviation

Progression of the mean EDSS scores over age. Legend: Progression in six groups of patients with relapsing–remitting onset multiple sclerosis and at least 30 years of follow-up (total of 738 patients). Group 1: patients with EDSS ≥ 3 at year 10 after disease onset (“never benign”). Groups 2–5: patients with benign multiple sclerosis (EDSS < 3 at year 10) but with EDSS worsening over 3 between different time points: years 10–15 (group 2), 15–20 (group 3), 20–15 (group 4) and 25–30 (group 5). Group 6: patients with EDSS < 3 at year 30 (“still benign” at the end of the study). EDSS: expanded disability status scale; SD: standard deviation

Discussion

In our population-based cohort of patients with relapsing–remitting onset MS, we found that 66.7% of patients had an EDSS score < 3 at year 10 after DO and that these patients had a 0.26 probability (95% CI 0.26–0.32) of maintaining their benign status in the long term (i.e. at year 30). Predictive factors of this favorable outcome were a young age at onset and a good recovery after the first relapse. Moreover, we illustrate that the long-term course of patients with benign MS follows the two-stage model introduced by Leray and colleagues [5], and that the longer these patients remain in the benign state, the lower their final EDSS at advanced age. Consequently, even if having benign MS at year 10 does not prevent disability in the long run, this good status early on provides a long-lasting advantage.

The proportions of patients reported to have benign MS vary considerably in the literature [15] mainly because of a lack of consensus about the definition of benign MS. Using the definition of EDSS < 3 at year 10 after DO is highly inclusive and might explain why nearly two-thirds of our population-based cohort of patients with relapsing–remitting onset MS are classified as such. It is nevertheless higher than in any other published cohort using the same definition: 19% for Lauer and Firnhaber [16], for instance. However, these works use different criteria to diagnose MS and are based on small cohorts. Another recent French study of 874 patients with MS found that 57.7% of them had irreversible EDSS scores < 3 at year 10 [11]. Unlike ours though, this cohort was hospital—rather than population—based, and patients with low disability are less likely to be seen in secondary and tertiary health centers [17].

We looked for predictors of remaining benign in the long term. Not surprisingly, early variables known to influence the long-term outcomes in MS are associated with preserving an EDSS < 3 after year 10. A young age at onset had a strong association with this outcome. Age at DO has often been found to be associated with late disability [12, 18,19,20]. A good recovery after the first relapse is also associated with a lower probability of EDSS ≥ 3 after year 10, as evidenced by previous works [4, 12]. Patients treated with DMTs were more likely to worsen over EDSS 3. This indicates reverse causality: patients with severe disease are more likely to be treated with DMTs, but more likely to worsen despite their treatment. However, our study was not designed to evaluate the effect of DMTs on the EDSS course. Other variables were not significantly associated with the outcome in the multivariate model: especially a high frequency of relapses during the very first years of the disease. This discrepancy with other studies [21] might be explained by the population included in the analysis: patients with benign MS have very few relapses during the first 5 years of the disease in comparison with other cohorts (median: 2, IQR: 2, Table 1).

The current description of the mean EDSS course over the years from DO in patients with benign MS are in accordance with the first description of the two-stage model (Fig. 3) [5, 11]. EDSS score progression after the loss of the benign status can be identified as the second stage. After the loss of the benign status, EDSS accumulation is independent of the duration of the first stage and highly parallel between groups, progressively slowing and following an asymptotic course around EDSS 6, as described in the original model. This score was only reached at year 30 by those with the shortest time with EDSS < 3 (i.e., groups 1 and 2 in our C30) although it should be noted that the follow-up for the other patients was insufficient to reach this score. This asymptotic pattern at high scores of EDSS is also found in the few trajectory studies of disability in MS [22, 23], and could be explained by the non-linearity of the EDSS [24, 25]. A one-point increase on the EDSS at high scores means a far greater disability accumulation than at lower scores. Thus the slope of the mean EDSS progression over time decreases at higher scores, even if the real disability shows ongoing worsening. This pattern was not described by Leray and colleagues because they only reported the mean time between EDSS 0 and 3 (first stage) and 3 and 6 (second stage), rather than sampling the mean EDSS scores at given times from DO [5].

We wanted to describe the EDSS course according to patient age (Fig. 4). As evidenced with the Cox model in B10, a young age at DO is associated with a longer duration of the benign phase. The mean age at DO in the six groups of C30 varies from 23.6 (still benign at year 30, group 6) to 27.4 years (loss of the benign status between years 10 and 15, group 2). The age of the loss of the benign status is different in each group, with a large span varying from 59.3 (group 6) to 39.8 years (group 2). After this breakthrough, the worsening of the mean EDSS seems to be highly parallel between groups as is illustrated in the graph with disease duration on the X-axis (Fig. 3). However, the graph shows the consequence of this parallelism: at advanced ages, the score that patients reach in each group is very different, ranging from a low disability (< EDSS 4, group 6), to a significant loss of mobility (EDSS 6, groups 1–3). Those with the longest benign phase will not reach the highest scores and thus benefit from their first slow progression. This is especially evident in patients with at least 30 years of benign status whose mean EDSS score was under 4 at age 70. Subsequently, we did not find any catch-up effect on EDSS accumulation at advanced ages. This challenges the view of a final bottleneck of disability, as previously reported [18, 19, 26, 27]. The above-mentioned asymptotic pattern at high EDSS scores can also be seen in this graph. In patients with the shortest benign phases (groups 1–3), the mean EDSS curves seem to merge after a certain age. This pattern is not found for patients in groups 4–6, who endure an ongoing disability accumulation even late in life. A reasonable hypothesis for this is that if these patients could live until a very old age, their mean EDSS curves would show the same asymptotic pattern around 6. Crielaard and colleagues have previously described this pattern of EDSS course over the lifetime in patients with benign multiple sclerosis [28]. They illustrated three trend changes in the mean EDSS trajectory, with breakpoints at the mean ages 44 and 67, with the same asymptomatic EDSS course after the second breakpoint. This is in accordance with our results, except concerning the ages at breakpoints, which are dependent of the duration of the benign phase in our stratified graph. They also found a lower EDSS score at advanced age in their subgroup of patients with benign multiple sclerosis in comparison with those with non-benign multiple sclerosis, without differentiating patients with benign multiple sclerosis according to the duration of the benign phase.

Some limits to our study deserve to be mentioned. The possibility of selection bias cannot be eliminated. In our registry, patients with DO before the late nineties were retrospectively collected and some cases, especially more aggressive cases, might have been missed. However, while this may be true for B30 which is composed of patients with DO decades ago, it is not the case for the B10 cohort of patients with a more recent DO. The median survival time provided by the Kaplan–Meier method on B10 patients is thus less affected by the selection bias. Table 1 shows data of B30 that are biased in comparison with B10: patients of B30 have characteristics associated with a lower hazard of EDSS ≥ 3 such as a young age at diagnosis or few relapses during the first 5 years of the disease. Consequently, the proportions of patients in the five benign groups of B30 are probably affected with an over-representation of patients with a long-lasting benign phase. However, in these groups, the mean EDSS trajectories are probably not sensitive to this bias and appear still accurate. Another limit of our study is the lack of data about MRI, as active lesions have been found to be important predictors of disability accrual [29]. This is due to the limited accuracy of imaging data in EDMUS [14] and to the variability of radiological activity identification which is not standardized and depends on patients’ preferences and neurologists’ habits. Finally, the use of EDSS as indicative of benign MS and good long-term prognosis also constitutes a limit. The EDSS score is debatable since patients considered as benign may exhibit disabling non-motor symptoms including pain, fatigue and depression [30, 31], as well as cognitive disorders which are albeit less frequent in patients with benign MS [32]. However, other scales which have been shown to describe global disability differently are more recent and inapplicable to older patients. Moreover, the EDSS is the most commonly used scale to evaluate disability in MS [31, 32].

Conclusion

In an exhaustive population-based cohort of 3440 patients with relapsing–remitting onset multiple sclerosis, two-thirds had a benign form identified as an expanded disability status scale score < 3 at year 10 from disease onset. They were followed up for a median of 22 years, and had a 0.26 probability to remain benign 30 years after disease onset. Moreover, despite the loss of their benign status, the longer these patients remained in the benign state, the lower their final EDSS at advanced age. Moving forward, it would be interesting to evaluate whether a long benign phase due to effective treatment also results in a lower EDSS score at an advanced age, even after treatment failure.

Data availability, material and code

Data are not publicly available and may be obtained on reasonable request by sending a mail to the corresponding author, Guillaume Mathey (g.mathey@chru-nancy.fr). Data open for sharing are aggregated data and statistical analysis plans.

References

Compston A, Coles A (2008) Multiple sclerosis. Lancet Lond Engl 372:1502–1517. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7

Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA et al (2014) Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology 83:278–286. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000560

Kurtzke JF (1983) Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 33:1444–1452

Confavreux C, Vukusic S, Adeleine P (2003) Early clinical predictors and progression of irreversible disability in multiple sclerosis: an amnesic process. Brain J Neurol 126:770–782

Leray E, Yaouanq J, Le Page E et al (2010) Evidence for a two-stage disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain 133:1900–1913. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq076

Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A et al (2010) The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain J Neurol 133:1914–1929. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq118

Confavreux C, Vukusic S (2006) Age at disability milestones in multiple sclerosis. Brain J Neurol 129:595–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh714

Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden LS et al (2004) Disability in elderly people with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of baseline data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. NeuroRehabilitation 19:55–67

Skoog B, Runmarker B, Winblad S et al (2012) A representative cohort of patients with non-progressive multiple sclerosis at the age of normal life expectancy. Brain J Neurol 135:900–911. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr336

Sanai SA, Saini V, Benedict RH et al (2016) Aging and multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl 22:717–725. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516634871

Leray E, Coustans M, Le Page E et al (2013) “Clinically definite benign multiple sclerosis”, an unwarranted conceptual hodgepodge: evidence from a 30-year observational study. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl 19:458–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458512456613

Debouverie M, Pittion-Vouyovitch S, Louis S et al (2008) Natural history of multiple sclerosis in a population-based cohort. Eur J Neurol 15:916–921. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02241.x

El Adssi H, Debouverie M, Guillemin F, LORSEP Group (2012) Estimating the prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in the Lorraine region, France, by the capture-recapture method. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl 18:1244–1250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458512437811

Confavreux C, Compston DA, Hommes OR et al (1992) EDMUS, a European database for multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 55:671–676

Ramsaransing GSM, De Keyser J (2006) Benign course in multiple sclerosis: a review. Acta Neurol Scand 113:359–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00637.x

Lauer K, Firnhaber W (1987) Epidemiological investigations into multiple sclerosis in Southern Hesse. V. Course and prognosis. Acta Neurol Scand 76:12–17

Debouverie M, Laforest L, Van Ganse E et al (2009) Earlier disability of the patients followed in multiple sclerosis centers compared to outpatients. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl 15:251–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458508097919

Tremlett H, Paty D, Devonshire V (2006) Disability progression in multiple sclerosis is slower than previously reported. Neurology 66:172–177. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000194259.90286.fe

Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Daumer M et al (2011) Age and disability accumulation in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 77:1246–1252. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318230a17d

Guillemin F, Baumann C, Epstein J et al (2017) Older age at multiple sclerosis onset is an independent factor of poor prognosis: a population-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology 48:179–187. https://doi.org/10.1159/000479516

Tremlett H, Zhao Y, Rieckmann P, Hutchinson M (2010) New perspectives in the natural history of multiple sclerosis. Neurology 74:2004–2015. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e3973f

Palace J, Bregenzer T, Tremlett H et al (2014) UK multiple sclerosis risk-sharing scheme: a new natural history dataset and an improved Markov model. BMJ Open 4:e004073. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004073

Signori A, Izquierdo G, Lugaresi A et al (2017) Long-term disability trajectories in primary progressive MS patients: a latent class growth analysis. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517703800

Hyland M, Rudick RA (2011) Challenges to clinical trials in multiple sclerosis: outcome measures in the era of disease-modifying drugs. Curr Opin Neurol 24:255–261. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283460542

Meyer-Moock S, Feng Y-S, Maeurer M et al (2014) Systematic literature review and validity evaluation of the expanded disability status scale (EDSS) and the multiple sclerosis functional composite (MSFC) in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol 14:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-14-58

Confavreux C, Vukusic S (2006) Natural history of multiple sclerosis: a unifying concept. Brain J Neurol 129:606–616. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl007

Kremenchutzky M, Rice GPA, Baskerville J et al (2006) The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 9: observations on the progressive phase of the disease. Brain J Neurol 129:584–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh721

Crielaard L, Kavaliunas A, Ramanujam R et al (2019) Factors associated with and long-term outcome of benign multiple sclerosis: a nationwide cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-319913

Tintore M, Rovira À, Río J et al (2015) Defining high, medium and low impact prognostic factors for developing multiple sclerosis. Brain J Neurol 138:1863–1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv105

Solaro C, Brichetto G, Amato MP et al (2004) The prevalence of pain in multiple sclerosis: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Neurology 63:919–921

Correale J, Peirano I, Romano L (2012) Benign multiple sclerosis: a new definition of this entity is needed. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl 18:210–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458511419702

Sayao A-L, Bueno A-M, Devonshire V et al (2011) The psychosocial and cognitive impact of longstanding “benign” multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl 17:1375–1383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458511410343

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants, the research nurses, clinical coordinators, technicians and statistics team for their contributions to patient care and conduct of the protocol. We also thank Felicity Neilson from Matrix Consultants for assistance in English language editing.

Funding

The ReLSEP registry is funded by an Inserm annual grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guillaume Mathey had a major role in the acquisition of data, design and conceptualized study. He interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. Guillaume Pisché interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. Marc Soudant analyzed the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Sophie Pittion-Vouyovitch had a major role in the acquisition of data. Francis Guillemin interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Marc Debouverie had a major role in the acquisition of data, interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Jonathan Epstein designed and conceptualized the study, analyzed and interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Guillaume Mathey has served on boards by BIOGEN, ROCHE, and NOVARTIS in the past 3 years but never received any personal or institutional financial compensation. Guillaume Pisché reports no competing interests. Marc Soudant reports no competing interests. Sophie Pittion-Vouyovitch has served on boards and received personal financial compensation by BIOGEN, ROCHE, TEVA, and NOVARTIS in the past 3 years. Francis Guillemin reports no competing interests. Marc Debouverie reports no competing interests. Jonathan Epstein reports no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Data collection was approved by the French National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties (CNIL n°913001). All the patients of the ReLSEP database are informed that their data are recorded and may be used for research purposes according to the French legislation. Patient written consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mathey, G., Pisché, G., Soudant, M. et al. Long-term analysis of patients with benign multiple sclerosis: new insights about the disability course. J Neurol 268, 3817–3825 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10501-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10501-0