Abstract

Carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) is an abnormal vascular shunt from the carotid artery to the cavernous sinus. They are commonly classified based on hemodynamics, etiology or anatomically. Hemodynamic classification refers to whether the fistula is high or low flow. Etiology is commonly secondary to trauma or can occur spontaneously in the setting of aneurysm or medical conditions predisposing to arterial wall defects. Bilateral carotid cavernous fistulas are rare. We present a case of bilateral CCF secondary to trauma. Ophthalmology was urgently consulted to assess the patient in the intensive care unit (ICU) for red eye. The patient was found to have decreased vision, increased intraocular pressure, an afferent pupillary defect, proptosis, chemosis, and ophthalmoplegia. Subsequent neuro-imaging confirmed a bilateral CCF. The patient underwent two endovascular embolization procedures. Trauma is the most common cause of CCF and accounts for up to 75% of cases. Most common signs of CCF depend on whether it is high or low flow. High-flow CCF may present with chemosis, proptosis, cranial nerve palsy, increased intraocular pressure, diplopia, and decreased vision. Cerebral angiography is the gold standard diagnostic modality. First-line treatment consists of endovascular embolization with either a metallic coil, endovascular balloon or embolic agent. It is unclear in the literature if bilateral cases are more difficult to treat or have a different prognosis. Our patient required two endovascular procedures suggesting that endovascular intervention may have reduced efficacy in bilateral cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Case history

A 17-year-old female was transferred to our hospital 4 days after being involved in a motor vehicle accident, in which she was the only survivor. She was diagnosed with a diffuse axonal injury, right femoral fracture, right peroneal nerve injury, left knee dislocation, mandible fractures, and diabetes insipidus. Ophthalmology was consulted for red eye with limited extraocular movements. Initial computed tomography scan of the orbits was reported as normal. She had no significant past medical or ophthalmic history.

Physical exam

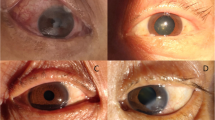

On bedside exam in the ICU visual acuity could not reliably be assessed due to sedation. Subsequent evaluation revealed a Snellen visual acuity of 20/200 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye. Pupils were 1 mm bilaterally with afferent defect appreciated in the right eye. Intraocular pressures measured 25 mmHg in the right eye and 21 mmHg in the left eye with Tonopen tonometry. Extraocular movements were severely restricted in all gaze directions in the right eye and full in the left. Exophthalmometry showed 2 mm of proptosis on the right side. Anterior segment examination demonstrated engorged and tortuous vessels in the right eye with segmental subconjunctival hemorrhage. There was segmental subconjunctival hemorrhage in the left eye. Posterior examination revealed a cup to disc ratio of 0.2 bilaterally, normal vasculature and normal peripheral retina exam (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) is an abnormal vascular shunt from the carotid artery to the cavernous sinus. They are commonly classified based on hemodynamics, etiology or anatomically. Hemodynamic classification refers to whether the fistula is high or low flow. Etiology is commonly secondary to trauma or can occur spontaneously in the setting of aneurysm or medical conditions predisposing to arterial wall defects. Anatomic classification specifies whether the fistula is direct, arising from the carotid artery, or indirect; arising from one of the branches of the carotid artery.

There are four types of CCF based on Barrow’s classification system as seen in the paper by Ellis et al [1]. Type A is defined as direct high-flow lesion, often resulting from a single tear in the internal carotid artery wall. Type A CCF often result from trauma or may arise from an aneurysmal rupture and account for approximately 80% of CCF’s [1]. Type B CCF is low-flow indirect lesion arising from the meningeal branches of the internal carotid artery. Type C CCF arises from the meningeal branches of the external carotid artery. Type D is low flow and arises from the meningeal branches of both the internal and external carotid artery.

Trauma is the most common cause of CCF and accounts for up to 75–80% [1]. They predominantly occur in young males, who have a higher incidence of trauma. They are seen in up to 4% of patients who have sustained a basilar skull fracture [2]. CCF are thought to arise from either a direct tear from bony fracture or shear forces secondary to trauma. Spontaneous CCFs typically occur in older females as a result of ruptured internal carotid artery aneurysms or secondary to fibromuscular dysplasia, Ehlers-Danlos, and pseudoxanthoma elasticum [1].

Most common signs of CCF are dependent on whether the CCF is direct or indirect. Direct will commonly present rapidly with signs of chemosis (94%), proptosis (87%), increased intraocular pressure (60%), cranial nerve palsy (54%), diplopia (51%), and impaired vision (28%) [1, 4]. Orbital bruits, headache, and orbital pain may also be presenting features [1, 3]. Indirect CCF tends to present less dramatically with conjunctival injection often being the presenting sign, making diagnosis challenging. Cerebral angiography is the gold standard diagnostic modality. Non-contrast CT, MRI, or angiographic CT or MRI may also help to demonstrate the presence of a CCF [1].

First-line treatment consists of endovascular embolization with either a metallic coil, endovascular balloon or embolic agent. Complications include cerebral infarction, retroperitoneal hematoma, decreased visual acuity and ophthalmoplegia in up to 5% of patients [1]. In one series by Gupta et al., 88.8% of endovascular interventions for CCF were effective in curing the patient [5]. Surgical intervention may be considered in cases where endovascular treatment has been unsuccessful or is not possible. Success rates have been reported between 30 and 80% in the literature [1]. Radiosurgery appears to be effective in patients with indirect, low flow, CCF’s [5].

Bilateral CCFs are rare. A recent case report and literature review article of bilateral CCF found a total of 67 cases since 1954, 41 of which were post-traumatic [6]. All the cases with known patient details, had ocular involvement at initial presentation and were type A CCFs. Surgical ligation was employed more frequently in the earlier reported cases. However, it has mainly been replaced with transarterial endovascular embolization, which was first reported in 1987 [20]. An additional three cases were found on our search of literature that were not included in this recent review [28, 38, 40]. Table 1 summarizes all cases of post-traumatic bilateral CCFs with reported patient presentation, treatment and outcome.

In this case, ophthalmic consultation was sought for red eye with decreased eye movements. Ophthalmic exam revealed significant proptosis, chemosis, and elevated intraocular pressures, which in the setting of trauma suggested a possible CCF. Review of neuroimaging by the on-call ophthalmology resident confirmed the diagnosis of a bilateral CCF. The patient underwent endovascular embolization, which, was initially successful in treating her CCF. Unfortunately, she presented 1 month later with recurrent symptoms and endovascular intervention needed to be repeated. Second attempt at endovascular intervention was successful. Her visual acuity returned to 20/25 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left using Snellen visual acuity chart. Intraocular pressure returned to a normal range. Her afferent pupillary defect resolved. Her right eye had a persistent 6th nerve palsy throughout.

We were unable to determine if bilateral CCF’s vary in response to intervention compared to unilateral based on the literature available. In this case, two attempts at unilateral transarterial balloon on the most severely affected side were required to resolve the CCF.

References

Ellis JA, Goldstein BS, Connoly ES, Meyers PM (2012) Carotid-cavernous fistulas. Neurosurg Focus 32(5):E9

Liang W, Xiaofeng Y, Weiguo L, Wusi Q, Gang S, Xuesheng Z (2007) Traumatic carotid cavernous fistula accompanying basilar skull fracture: a study on the incidence of traumatic carotid cavernous fistula in the patients with basilar skull fracture and the prognostic analysis about traumatic carotid cavernous fistula. J Trauma 63:1014–1020

De Keizer R (2003) Carotid cavernous and orbital arteriovenous fistulas: ocular features, diagnostics, and hemodynamic considerations in relation to visual impairment and morbidity. Orbit 22:121–142

Kirsch M, Henkes H, Liebig T, Weber W, Esser J, Golik S, Kuhne D (2006) Endovascular management of dural carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas in 141 patients. Neuroradiology 48:486–490

Gupta AK, Purkayastha S, Krishnamoorthy T, Bodheey NK, Kapilamoorthy TR, Kesavadas C et al (2006) Endovascular treatment of direct carotid cavernous fistulae: a pictorial review. Neuroradiology 48:831–839

Al-Mufti F, Amuluru K, El-Ghanem M et al (2017) Spontaneous bilateral carotid-cavernous fistulas secondary to cavernous sinus thrombosis. Neurosurgery 80:646–654

Mason TH, Swain GM, Osheroff HR (1954) Bilateral carotid-cavernous fistula. J Neurosurg 11:323–326

Jamieson KG (1964) Bilateral carotico-cavernous fistulae. Hypopituitarism from bilateral carotid ligation for surgical cure. Aust NZ J Surg 34:1–10

Clemens F, Lodin H (1968) Some viewpoints on the venous outflow pathways in cavernous sinus fistulas: angiographic study of five traumatic cases. Clin Radiol 19:196–200

Curl FD, Harbert JC, Luessenhop AD, Di Chiro G, Kamm RF (1972) Radionuclide cerebral angiography in a case of bilateral carotid-cavernous fistula. Radiology 102:391–392

Mullan S (1974) Experiences with surgical thrombosis of intracranial berry aneurysms and carotid cavernous fistulas. J Neurosurg 41:657–670

Roosen K, Grote W (1975) Diagnosis and treatment of bilateral traumatic carotid-cavernous sinus fistulae. Neurochirurgia 18:175–189

Conley FK, Hamilton RD, Hosobuchi Y (1975) Successful surgical treatment of bilateral carotid-cavernous fistulas. J Neurosurg 43:357–361

Dardenne GJ (1975) Bilateral traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulae. Surg Neurol 3:105–107

Graziussi G, Granata F, Terracciano S (1977) Bilateral carotid-cavernous fistula of traumatic origin. A case report. Acta Neurol 32:347–353

Ambler MW, Moon AC, Sturner WQ (1978) Bilateral carotid-cavernous fistulae of mixed types with unusual radiological and neuropathological findings. J Neurosurg 48:117–124

Donnell MS, Larson SJ, Correa-Paz F, Worman LW (1978) Traumatic bilateral carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas with progressive unilateral enlargement. Surg Neurol 10:115–118

Laws ER Jr, Onofrio BM, Pearson BW, McDonald TJ, Dirrenberger RA (1979) Successful management of bilateral carotid-cavernous fistulae with a transsphenoidal approach. Neurosurgery 4:162–167

West CGH (1980) Bilateral carotid-cavernous fistulae: a review. Surg Neurol 13:85–90

Matsui Y, Yamada K, Hayakawa T et al (1987) Bilateral traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas. Case report. Neurol Med Chir 27:447–450

vd Vliet AM, Rwiza HT, Thijssen HO et al (1987) Bilateral direct carotid-cavernous fistulas of traumatic and spontaneous origin: two case reports. Neuroradiology 29:565–569

Kim JK, Seo JJ, Kim YH, Kang HK, Lee JH (1996) Traumatic bilateral carotid-cavernous fistulas treated with detachable balloon. A case report. Acta Radiol 37:46–48

Ng SH, Wan YL, Ko SF et al (1999) Bilateral traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas successfully treated by detachable balloon technique. J Trauma 47:1156–1159

Alkhani A, Willinsky R, TerBrugge K (1999) Spontaneous resolution of bilateral traumatic carotid cavernous fistulas and development of trans-sellar intercarotid vascular communication: case report. Surg Neurol 52:627–629

Kamel HA, Choudhari KA, Gillespie JS (2000) Bilateral traumatic caroticocavernous fistulae: total resolution following unilateral occlusion. Neuroradiology 42:462–465

Churojana A, Chawalaparit O, Chiewwit P, Suthipongchai S (2001) Spontaneous occlusion of a bilateral post traumatic carotid cavernous fistula. Interv Neuroradiol 7:245–252

Sanden U, Grosse U, Jaksche H (2003) Visualization of bilateral carotid cavernous sinus fistulas with duplex sonography. J Clin Ultrasound 31:319–323

Oran I, Bozkaya H, Parildar M (2004) Embolisation of both fistulae through the same carotid artery tear in a patient with bilateral traumatic caroticocavernous fistulae. Neuroradiology 46:234–237

Moron FE, Klucznik RP, Mawad ME, Strother CM (2005) Endovascular treatment of high-flow carotid cavernous fistulas by stent-assisted coil placement. Am J Neuroradiol 26:1399–1404

Hantson P, Espeel B, Guerit JM, Goffette P (2006) Bilateral carotid-cavernous fistula following head trauma: possible worsening of brain injury following balloon catheter occlusion? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 108:576–579

Luo CB, Teng MM, Chang FC et al (2007) Bilateral traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulae: strategies for endovascular treatment. Acta Neurochir 149:675–680 (discussion 680)

Liang W, Xiaofeng Y, Weiguo L et al (2007) Bilateral traumatic carotid cavernous fistula: the manifestations, transvascular embolization and prevention of the vascular complications after therapeutic embolization. J Craniofac Surg 18:74–77

Gao BL, Zhao W, Xu GP (2009) The development of a de novo indirect carotidcavernous fistula after successful occlusion of bilateral direct carotid-cavernous fistulas. J Trauma 66:E28–E31

Gierthmuehlen M, Schumacher M, Zentner J, Hader C (2010) Brainstem compression caused by bilateral traumatic carotid cavernous fistulas: case report. Neurosurgery 67:E1160–E1163 (discussion E1163-E1164)

Cho K-C, Seo D-H, Choe I-S, Park S-C (2011) Cerebral hemorrhage after endovascular treatment of bilateral traumatic carotid cavernous fistulae with covered stents. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 50:126–129

Yu Y, Huang Q, Xu Y, Hong B, Zhao W et al (2012) Use of onyx for transarterial balloon-assisted embolization of traumatic carotid cavernous fistulas: a report of 23 cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 33:1305–1309

Gapsis BC, Ranjit RU, Malavade S et al (2013) Spontaneous resolution of ophthalmologic symptoms following bilateral traumatic carotid cavernous fistulae. Digit J Ophthalmol 19:33–38

Maciej W, Tadeusz P, Pawel B et al (2013) Posttraumatic bilateral carotid-cavernous fistula. J Int Adv Otol 9:417–422

Chiriac A, Iliescu BF, Dobrin N, Poeata I (2014) One-step endovascular treatment of bilateral traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulae with atypical clinical course. Turk Neurosurg 24:422–426

Ke L, Yang Y, Yuan J (2017) Bilateral carotid-cavernous fistula with spontaneous resolution: a case report and literature review. Medicine 96(19):e6869

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Docherty, G., Eslami, M., Jiang, K. et al. Bilateral carotid cavernous sinus fistula: a case report and review of the literature. J Neurol 265, 453–459 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-017-8657-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-017-8657-y