Abstract

Introduction

Educational programs on chronic cough may improve patient care, but little is known about how Canadian physicians manage this common debilitating condition. We aimed to investigate Canadian physicians’ perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge of chronic cough.

Methods

We administered a 10-min anonymous, online, cross-sectional survey to 3321 Canadian physicians in the Leger Opinion Panel who managed adult patients with chronic cough and had been in practice for > 2 years.

Results

Between July 30 and September 22, 2021, 179 physicians (101 general practitioners [GPs] and 78 specialists [25 allergists, 28 respirologists, and 25 ear/nose/throat specialists]) completed the survey (response rate: 5.4%). In a month, GPs saw a mean of 27 patients with chronic cough, whereas specialists saw 46. About one-third of physicians appropriately identified a duration of > 8 weeks as the definition for chronic cough. Many physicians reported not using international chronic cough management guidelines. Patient referrals and care pathways varied considerably, and patients frequently experienced lost to follow-up. While physicians endorsed nasal and inhaled corticosteroids as common treatments for chronic cough, they rarely used other guideline-recommended treatments. Both GPs and specialists expressed high interest in education on chronic cough.

Conclusion

This survey of Canadian physicians demonstrates low uptake of recent advances in chronic cough diagnosis, disease categorization, and pharmacologic management. Canadian physicians also report unfamiliarity with guideline-recommended therapies, including centrally acting neuromodulators for refractory or unexplained chronic cough. This data highlights the need for educational programs and collaborative care models on chronic cough in primary and specialist care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic cough is a prevalent and debilitating condition that increases in incidence with age [1]. Although chronic cough can be caused by underlying conditions—such as asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), or use of medications (i.e., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) [2,3,4]—in many patients, there remains no identifiable cause [5]. Due to the complex and often multifactorial etiology of chronic cough, its diagnosis and treatment span multiple medical specialties. Management of chronic cough can thus involve healthcare professionals ranging from general practitioners to medical and surgical subspecialists [6].

The 2020 European Respiratory Society (ERS) [7] and 2018 American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines [8] define chronic cough as a cough that persists for > 8 weeks. These guidelines also include the terms “refractory chronic cough” (RCC)—coughing that persists despite optimal treatment of underlying conditions—and “unexplained chronic cough” (UCC)—coughing with no underlying cause despite thorough investigation [7,8,9]. Since many patients with chronic cough present with a sensitive cough reflex to low levels of thermal, chemical, and mechanical stimulation, guidelines now refer to this pathophysiological phenomenon as “cough hypersensitivity syndrome” (CHS) [7, 10].

Chronic cough can cause substantial burden on both patients and healthcare systems [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Approximately half of patients with RCC or UCC report more than 20 coughs/hour along with symptoms of hoarseness and chest/stomach pains [16]. In addition to these physical symptoms, chronic cough can have substantial impact on psychosocial well-being [12, 17]. Almost all chronic cough patients (96%) in a European survey reported that cough impacts their health-related quality of life [18]. Sleep loss/disruption and social embarrassment represent other common concerns [15]. In the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, baseline or incident chronic cough was associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms and psychological distress [19]. A recent U.S. survey also found that individuals with chronic cough had a two-fold increase in hospitalizations and emergency department visits compared to individuals without chronic cough [12].

Although recently published guidelines inform optimal management of chronic cough, diagnosis and treatment of this condition remains challenging [9, 20] and studies support the need for more educational resources [21]. To inform future education on chronic cough among Canadian physicians, we conducted a survey investigating Canadian physicians’ perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge of chronic cough.

Methods

Study Design

We administered a 10-min, online, cross-sectional survey to anonymous Canadian physicians. Without review of clinical data or patient registries, physicians responded based on their experience and perceptions of their clinical practice. The study, which did not collect patient or clinical data, did not require ethics board review.

We developed our survey from a prior Spanish questionnaire designed by allergists, general practitioners, and respirologists exploring perceptions and practices for the diagnosis and management of chronic cough [22]. Survey questions had pre-populated (closed) response options and employed different scales depending on the question. The survey, available in English and French, collected physicians’ demographics, their perceived diagnosis and management of chronic cough, their perceived impact of chronic cough on patients’ quality of life, and need for education on chronic cough (Supplementary Appendix).

Leger Marketing hosted the survey online and on mobile applications for smartphones and tablets. We made the survey available for 6 weeks between July 30 to September 22, 2021. All collected data were de-identified.

Survey Participants

To ensure broad Canadian physician representation, we recruited survey participants based on specialty and province of practice through the Leger Marketing LEO (Leger Opinion) panel. The Leger Opinion consumer panel consists of ~ 500,000 active Canadian members, among which 50,000 represent health care providers (HCPs). HCPs registered with LEO must undergo verification that includes manual confirmation from local colleges. We distributed our survey to 3321 HCPs in the Leger Opinion who potentially met eligibility to participate in the study. To enroll in the study, participants had to (1) be a general practitioner (GP), allergist, respirologist, or ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist who saw patients with chronic cough in their clinical practice; (2) be in active clinical practice for ≥ 2 years and spend ≥ 60% of their time every week in direct patient care; (3) see ≥ 75 adult patients per month across all conditions; and (4) provide electronic informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

This exploratory study had no a priori sample size calculation. We enrolled a non-probability sample and performed descriptive statistics on complete data.

Results

Between July 30 and September 22, 2021, we invited 3321 potentially eligible Canadian HCPs to participate in the survey. Among those invited, 179 proved eligible and completed the full survey (response rate: 5.4%). The 179 HCPs included 101 GPs and 78 specialists (25 allergists, 28 respirologists, and 25 ENTs). Respondents were mostly male, based in Ontario, had been in practice for approximately 20 years, and saw over 250 adult patients per month (Table 1).

Use of Terms and Guidelines for Chronic Cough

Both GPs and specialists endorsed variable definitions for chronic cough (Fig. 1A). Seven percent of GPs and 12% of specialists did not have a set criterion for defining chronic cough. While diagnosing, over 65% of GPs and specialists used the terms RCC and UCC “often” or “sometimes”, but the other one-third “rarely” or “never” used these terms. Respondents used the term CHS less frequently (Fig. 1B). More specialists than GPs reported having high familiarity (8–10 on a 10-point scale ranging from “1 = not familiar at all” to “10 = very familiar”) with the CHEST (44% vs 8%) and ERS (27% vs 3%) guidelines for chronic cough (Fig. 1C). Few GPs chose “often” as the frequency with which they followed the guidelines. Higher proportions of specialists (21% [ERS] to 31% [CHEST]) often followed the guidelines, but another 24% (CHEST) to 31% (ERS) never followed them (Fig. 1D).

Physicians’ use of (A) definitions and (B) terminology for chronic cough, (C) familiarity with CHEST and ERS guidelines, and (D) use of CHEST and ERS chronic cough guidelines. CHS cough hypersensitivity syndrome, CHEST American College of Chest Physicians, ERS European Respiratory Society, GP general practitioner, RCC refractory chronic cough, UCC unexplained chronic cough

Perceptions of Chronic Cough

About one-quarter of specialists considered RCC (26%) and UCC (28%) to “often” represent a distinct disease compared with 5% and 7% of GPs (Fig. 2). Specialists, more frequently than GPs, perceived RCC and UCC to “often” represent a symptom of either a respiratory (26% RCC and 23% UCC) or non-respiratory (18% RCC and 22% UCC) disease (Fig. 2).

A smaller proportion of GPs (30%) than specialists (60%) endorsed chronic cough as a more frequent symptom in women than in men; 36% of GPs expressed uncertainty. GPs and specialists had similar perceptions about other aspects of chronic cough (Supplemental Fig. 1A).

Approximately half of the surveyed physicians (48% of GPs and 50% of specialists) highly agreed (8–10 on a 10-point scale ranging from “1 = not agree at all” to “10 = maximum agreement”) that chronic cough disappears when the underlying disease is treated (Supplemental Fig. 1B). A substantial proportion of physicians also highly agreed that, after a while, chronic cough usually disappears by itself (26% of GPs and 26% of specialists) or that chronic cough does not usually disappear by itself but persists over time (20% of GPs and 29% of specialists).

Most physicians (54% of GPs and 65% of specialists) perceived chronic cough to have high impact (8–10 on a 10-point scale ranging from “1 = no impact” to “10 = very high impact”) on patients’ quality of life, while 44% of GPs and 33% of specialists considered this disease to have moderate impact. Sixty-five percent of GPs and 59% of specialists believed chronic cough to have high impact on sleep (Supplemental Fig. 2). Other areas believed to be highly impacted included physical activity/exercise (56% of GPs and 41% of specialists) and social life (44% of GPs and 58% of specialists).

Chronic Cough in Physicians’ Practices

Based on the definition of chronic cough as a cough lasting > 8 weeks, GPs reported seeing an average of 27 patients with chronic cough in a typical month (6% of their total monthly patients), while specialists reported seeing 46 patients (16% of their total monthly patients). To educate and answer chronic cough-related questions with patients, GPs reported spending an average of 17 min, whereas specialists reported 23 min. Both times are comparable to the average visit time for complex multi-system diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and type 2 diabetes. Physicians endorsed asthma, GERD, and rhinitis/upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) as common etiologies for chronic cough (Supplemental Fig. 3).

GPs reported that they “often” or “sometimes” refer patients with chronic cough to a respirologist (86%), ENT specialist (81%), allergist (68%), gastroenterologist (53%), pharmacist (26%), or psychiatrist (10%). Specialists also reported frequent referrals to respirologists (74%), ENTs (77%), allergists (70%), gastroenterologists (56%), pharmacists (28%), and psychiatrists (28%).

Diagnosis of Chronic Cough

Fewer GPs (44%) than specialists (56%) had diagnostic protocols for chronic cough in their practices. Most physicians (66% of GPs and 71% of specialists) considered diagnostic protocols for chronic cough as “very necessary” or “necessary”; the remaining respondents considered the protocols “slightly necessary” or “not necessary”.

Diagnostic tests frequently ordered by GPs and specialists (8–10 points on a 10-point scale ranging from “1 = never perform” to “10 = always perform”) included chest radiography (86% of GPs and 85% of specialists), followed by spirometry (52% of GPs and 67% of specialists) (Supplemental Fig. 4A). GPs estimated that 71% of their patients with chronic cough, versus 64% of those seen by specialists, received a diagnosis or had underlying causes ruled out in < 6 months. In a minority of patients (11% for GPs and 16% for specialists), physicians believed that a diagnosis of chronic cough could take > 1 year (Supplemental Fig. 4A).

Treatment and Follow-up of Chronic Cough

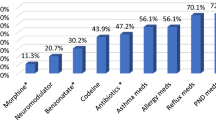

Sixty-three percent of GPs and 69% of specialists reported frequently prescribing nasal corticosteroids for chronic cough (Fig. 3). GPs and specialists also frequently prescribed inhaled corticosteroids, inhaled bronchodilators, and proton pump inhibitors. Fewer than 5% of GPs and < 25% of specialists prescribed neuromodulators, including pregabalin, gabapentin and morphine.

Over half of GPs (62%) and specialists (53%) reported that they “often” began treatment and assumed follow-up, but other care patterns involving follow-up by different specialists were also endorsed (Fig. 4A). Specialists frequently referred patients back to GPs; 15% reported that they “often” referred patients to a GP after beginning treatment, and another 15% indicated that they “often” referred to a GP without prescribing treatment. Both GPs (17%) and specialists (41%) reported that patients were “often” lost to follow-up. Compared to specialists, more GPs perceived chronic cough as “usually controlled in primary care” than “usually controlled in pneumonology” (Fig. 4B).

Education in Chronic Cough

Twelve percent of GPs and 36% of specialists reported attending a training course or activity related to chronic cough. Forty-nine percent of GPs and 60% of specialists indicated high interest in receiving additional training on the management of chronic cough (Supplemental Fig. 5).

Discussion

Summary of Findings

Our survey of Canadian physicians reveals that GPs and specialists lack familiarity with the definitions and guidelines in chronic cough; that most physicians do not consider RCC/UCC to represent distinct disease entities; that physicians estimate investigations of chronic cough to take > 6 months in about one-third of patients; that centrally acting neuromodulators remain rarely prescribed; and that many chronic cough patients are lost to follow-up.

Findings in Context

Although current guidelines define chronic cough as a cough lasting > 8 weeks [7, 8], the definition and nomenclature have changed over time. An acute post-viral cough usually self-limits within 3 weeks, so guidelines initially considered cough lasting > 3 weeks as an appropriate definition [23]. Longitudinal follow-up of post-viral coughs suggested, however, that they may take up to 8 weeks to resolve [24, 25]. In a systematic review examining prevalence of chronic cough, most primary studies conducted between 1980 and 2013 used the British Medical Research Council’s definition of chronic bronchitis—a cough duration of ≥ 3 months in 2 consecutive years—as the threshold duration for chronic cough [26]. Recent clinical trials in chronic cough have used a minimum duration of 12 months to allow time for adequate assessment, investigations, and treatment trials [27, 28] that more confidently render a diagnosis of RCC or UCC. Our finding of variable responses regarding diagnostic criteria for chronic cough are thus unsurprising and underscore the need for better education on recent guidelines and practice updates.

Although two-thirds of respondents used the terms RCC and UCC in their practice, they generally regarded these conditions as symptoms of underlying diseases rather than diseases of themselves. Clinical trials employ the terms RCC and UCC [27,28,29,30], but the terminology may not yet be fully integrated into clinical practice. ERS [7] and CHEST [8] guidelines suggest that the diagnosis of RCC or UCC requires appropriate testing and/or empirical trials of treatment. The results from this survey suggest that these diagnostic protocols may not be fully used in clinical practice. Physicians may avoid the term UCC, particularly when they suspect that neuronal dysregulation (i.e., CHS) is the underlying cause for cough and thus not truly “unexplained.” CHS provides a useful pathophysiological term, but there are no agreed upon diagnostic criteria or objective tests for this condition. This may explain the less frequent usage of CHS compared to RCC and UCC.

Although respondents estimated that around two-thirds of patients received a diagnosis or had underlying causes ruled out within the first 6 months of care, about one-third of patients had this process take more than 6 months. For some patients, delays in referrals and tests likely contribute to this extended time to diagnosis. The long time estimated to diagnose chronic cough supports the entry criterion of coughing for > 12 months employed in recent clinical trials [27, 28].

Chronic cough management surveys from other countries [13, 22, 31] similarly demonstrate that, particularly among GPs, there remains low use of guideline-recommended therapies such as gabapentin, morphine, and pregabalin [7, 8, 32]. Low and delayed adoption of clinical guidelines can occur across multiple therapeutic areas [33, 34] and may relate to varying factors including lack of awareness/familiarity, guideline complexity, and organizational constraints [35]. Physician and/or patient fears, confirmed by qualitative research, represent major barriers to guideline uptake [36]. Related to chronic cough, patients and physicians may have concerns about well-known opiate-related toxicities, dependance [37], and neuromodulator adverse effects [38]. The treatment of chronic cough includes an off-label use of neuromodulators and the data to support their efficacy is primarily based on subjective cough assessments and low-quality evidence from small studies [7, 39]. Surveys have found that neither patients nor physicians perceive neuromodulators to be effective therapies [14, 15, 21]. Other guideline-recommended therapies, such as speech therapy, are not well established across Canada, and their long-term effects on cough frequency requires further investigation [40]. These issues support the need for large randomized trials that provide evidence of additional treatment options for chronic cough.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study represents the first to investigate Canadian physicians’ perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge of chronic cough. Limitations of our study include, however, restricted sampling of physicians in the Leger Opinion panel; a low response rate; possible sampling bias toward physicians who have greater interest in or knowledge of chronic cough; low geographic representation in certain parts of Canada; potential self-report biases; and a small sample size.

Implications and Conclusions

Our survey findings highlight the need for better education on chronic cough and improved collaborative care models with clear referral and management paths between GPs and specialists. Future programs to address educational gaps may improve patient outcomes and reduce the substantial burden of chronic cough on physicians, patients, and the healthcare system.

References

Satia I, Mayhew AJ, Sohel N et al (2021) Prevalence, incidence, and characteristics of chronic cough among adults from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). ERJ Open Res 7(2):00160–02021. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00160-2021

Smyrnios NA, Irwin RS, Curley FJ (1995) Chronic cough with a history of excessive sputum production. The spectrum and frequency of causes, key components of the diagnostic evaluation, and outcome of specific therapy. Chest 108(4):991–997. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.108.4.991

Dicpinigaitis PV (2006) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 129(1 Suppl):169S-173S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.169S

Farooqi MAM, Cheng V, Wahab M, Shahid I, O’Byrne PM, Satia I (2020) Investigations and management of chronic cough: a 2020 update from the European Respiratory Society Chronic Cough Task Force. Pol Arch Intern Med 139(9):789–795. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.15484

Haque RA, Usmani OS (2005) Barnes PJ (2005) Chronic idiopathic cough: a discrete clinical entity? Chest 127(5):1710–1713. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.127.5.1710

Kaplan AG (2019) Chronic cough in adults: make the diagnosis and make a difference. Pulm Ther 5(1):11–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-019-0089-7

Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K et al (2020) ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J 55(1):1901136. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01136-2019

Irwin RS, French CL, Chang AB, Altman KW, CHEST Expert Cough Panel (2018) Classification of cough as a symptom in adults and management algorithms. CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 153(1):196–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.016

Satia I, Wahab M, Kum E et al (2021) Chronic cough: investigations, management, current and future treatments. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med 5(6):404–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2021.1979904

Morice AH, Millqvist E, Belvisi MG et al (2014) Expert opinion on the cough hypersensitivity syndrome in respiratory medicine. Eur Respir J 44(5):1132–1148. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00218613

Hull JH, Langerman H, ul-Haq Z, Kamalati T, Lucas A, Levy ML (2021) Burden and impact of chronic cough in UK primary care: a dataset analysis. BMJ Open 11:e054832. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054832

Meltzer EO, Zeiger RS, Dicpinigaitis P et al (2021) Prevalence and burden of chronic cough in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 9(11):4037-4044.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2021.07.022

Zeiger RS, Schatz M, Butler RK, Weaver JP, Bali V, Chen W (2020) Burden of specialist-diagnosed chronic cough in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 8(5):1645–1657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.01.054

Zeiger RS, Schatz M, Hong B et al (2021) Patient-reported burden of chronic cough in a managed care organization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 9(4):1624–1637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.018

Prenner B, Topp R, Beltyukova S, Fox C (2022) Referrals, etiology, prevalence, symptoms, and treatments of chronic cough. A survey of allergy specialists. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 20:22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2022.08.993

Dicpinigaitis PV, Birring SS, Blaiss M et al (2022) Demographic, clinical, and patient-reported outcome data from 2 global, phase 3 trials of chronic cough. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2022.05.003

Kum E, Guyatt GH, Munoz C et al (2022) Assessing cough symptom severity in refractory or unexplained chronic cough: findings from patient focus groups and an international expert panel. ERJ Open Res 8(1):00667–02021. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00667-2021

Chamberlain SAF, Garrod R, Douiri A et al (2015) The impact of chronic cough: a cross-sectional European survey. Lung 193(3):401–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/x00408-015-9701-2

Satia I, Mayhew AJ, Sohel N et al (2022) Impact of mental health and personality traits on the incidence of chronic cough in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. ERJ Open Res 8(2):00119–02022. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00119-2022

Chung KF, McGarvey L, Song WJ et al (2022) Cough hypersensitivity and chronic cough. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 8(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-022-00370-w

Gowan TM, Huffman M, Weiner M et al (2021) Management of chronic cough in adult primary care: a qualitative study. Lung 199(5):563–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-021-00478-y

Puente-Maestu L, Molina-París J, Trigueros JA et al (2021) A survey of physicians’ perception of the use and effectiveness of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in chronic cough patients. Lung 199(5):507–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-021-00475-1

Irwin RS, Boulet LP, Cloutier MM et al (1998) Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom. A consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest 114:133S-181S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.114.2_supplement.133s

Poe RH, Israel RH, Utell MJ, Hall WJ (1982) Chronic cough: bronchoscopy or pulmonary function testing? Am Rev Respir Dis 126(1):160–162. https://doi.org/10.1164/arrd.1982.126.1.160

Poe RH, Harder RV, Israel RH, Kallay MC (1989) Chronic persistent cough. Experience in diagnosis and outcome using an anatomic diagnostic protocol. Chest 95(4):723–728. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.95.4.723

Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S et al (2016) Defining chronic cough: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 8(2):146–155. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2016.8.2.146

Morice A, Smith JA, McGarvey L et al (2021) Eliapixant (BAY1817080), a P2X3 receptor antagonist, in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover pase 2a study. Eur Respir J 58(5):2004240. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.04240-2020

McGarvey LP, Birring SS, Morice AH et al (2022) Efficacy and safety of gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, in refractory chronic cough and unexplained chronic cough (COUGH-1 and COUGH-2): results from two double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet 399(10328):909–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02348-5

Ryan NM, Birring SS, Gibson PG (2012) Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 380(9853):1583–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60776-4

Chamberlain Mitchell SAF, Garrod R, Clark L et al (2017) Physiotherapy, and speech and language therapy intervention for patients with refractory chronic cough: a multicentre randomised control trial. Thorax 72(2):129–136. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-2008843

Leuppi JD, Guggisberg P, Koch D et al (2022) Understanding physician’s knowledge and perception of chronic cough in Switzerland. Curr Med Res Opin 38(8):1459–1466. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2022.2057154

Gibson P, Wang G, McGarvey L et al (2016) Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guidelines and expert panel report. Chest 149(1):27–44. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.15-1496

Overington JD, Huang YC, Abramson MJ et al (2014) Implementing clinical guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: barriers and solutions. J Thorac Dis 6(11):1586–1596. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.11.25

Howard M, Noppens R, Gonzalez N, Jones PM, Payne SM (2021) Seven years on from the Canadian Airway Focus Group Difficult Airway Guidelines: an observational survey. Can J Anaesth 68(9):1331–1336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02056-5

Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A (2016) Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation—a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel) 4(3):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030036

Jiang V, Marshall Brooks E, Tong ST et al (2020) Factors influencing update of changes to clinical preventive guidelines. J Am Board Fam Med 33(2):271–278. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2020.02.190146

Belzak L, Halverson J (2018) Evidence synthesis—the opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 38(6):224–233. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.38.6.02

Mattson CL, Chowdhury F, Gilson TP (2022) Notes from the field: trends in gabapentin detection and involvement in drug overdose deaths—23 states and the District of Columbia, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 71(19):664–666. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7119a3

Morice A, Dicpinigaitis P, McGarvey L, Birring SS (2021) Chronic cough: new insights and future prospects. Eur Respir Rev 30(162):210127. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0127-2021

Slinger C, Mehdi SB, Milan SJ et al (2019) Speech and language therapy for management of chronic cough. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7(7):CD013067. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013067

Acknowledgements

The authors of the study would like to thank the survey participants. We also thank Fusion MD Medical Science Network, Inc. (Montreal, Canada) for providing manuscript support with funding from Merck Canada, Inc.

Funding

The study and medical writing support was funded by Merck Canada, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work and the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. All authors were involved in drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

EK, DB, and MW report no conflicts of interest. ND is currently supported by the Canadian Asthma Allery and Immunology Foundation Type II Inflammation Sanofi Genzyme Award. TA and SS are employees of Merck Canada, Inc. KQ reports personal fees from Merck. PH reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Cyclomedica, Grifols, and Vertex, and speaker and/or consulting fees from Acceleron, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Grifols, Janssen, Sanofi Genzyme, Takeda, and Valeo. MC reports payment or honoraria speaking from GSK, AstraZeneca, Respiplus, Valeo and Covis. Has received support for attending meetings by Sanofi. Participated in advisory boards for Novartis, GSK, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Respiplus, Trudell, Valeo, CMD and Covis. PL reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and GSK. AE has participated in advisory boards for ALK Abello, AstraZeneca, Aralez, Bausch Health, LEO Pharma, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer, has been a speaker for ALK Abello, AstraZeneca, Miravo, Medexus, and Mylan. Her institution has received research grants from ALK Abello, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Bayer LLC, Medexus, Novartis, and Regeneron. She has also served as an independent consultant to Bayer LLC and Regeneron. LPB has previously received research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, GSK, Merck, Novartis, and Sanofi-Regeneron and speaker and/or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Covis, Novartis, GSK, Merck, and Sanofi-Regeneron. AK is a member of advisory boards/speaker’s bureaus for AstraZeneca, Behring, Belus, Boehringer Ingelheim, Covis, Cipla, Eisai, GSK, Merck Frosst, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva, Trudell, and Valeo. SKF served on an advisory board for Merck and sponsored talks for GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim. IS is currently supported by the E.J. Moran Campbell Early Career Award, McMaster University and reports grants from ERS Respire 3 Marie Curie fellowship, Merck, GSK and MITACS and speaker and/or consulting fees from Merck, GSK, AstraZeneca, Roche, Genentech and Respiplus.

Ethical Approval

This survey did not collect patient or clinical data and therefore did not require ethics board review.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kum, E., Brister, D., Diab, N. et al. Canadian Health Care Professionals’ Familiarity with Chronic Cough Guidelines and Experiences with Diagnosis and Management: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Lung 201, 47–55 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-023-00604-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-023-00604-y