Abstract

To evaluate oncologic and functional outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer included in an induction chemotherapy (ICT)-based larynx preservation program in daily clinical practice. All patients with locally advanced (T3/4, N0–3, M0) hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, technically suitable for total pharyngo-laryngectomy, treated by docetaxel (75 mg/m2, day 1), cisplatin (75 mg/m2, day 1) and 5-fluorouracil (750 mg/m2/day, day 1–5) (TPF)-ICT (2–3 cycles) for larynx preservation at our institution between 2004 and 2013, were included in this retrospective study. Prognostic factors of oncologic (overall, cause-specific and recurrence-free survival: OS, SS and RFS) and functional (dysphagia outcome and severity scale, permanent enteral nutrition, larynx preservation) outcomes were assessed in univariate and multivariate analyses. A total of 53 patients (42 men and 11 women, mean age 58.6 ± 8.2 years) were included in this study. Grade 3–4 toxicities were experienced by 17 (32 %) patients during ICT. The rate of poor response (response <50 % without larynx remobilization) to ICT was 10 %. At 5 years, OS, SS and RFS rates were 56, 60 and 54 %, respectively. Four patients required definitive enteral nutrition (permanent enteral tube feeding). The rate of patients alive, disease-free and with a functional larynx at 2 years was 58 %. T4 tumor stage (p = 0.005) and response to ICT <50 % (p = 0.02) were independent prognostic factors of OS. Response to ICT was significantly associated with the risk of permanent enteral nutrition (p = 0.04) and larynx preservation (p = 0.01). In daily clinical practice, a TPF-ICT-based larynx preservation protocol can be used in patients with locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer with satisfactory results in terms of tolerance, efficacy and oncologic and functional outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Most patients with hypopharyngeal cancer are diagnosed with locally advanced disease. Despite some advances in therapeutic management, patients with hypopharyngeal cancer still harbor a poor prognosis [1, 2]. With the development of organ preservation trials, total pharyngolaryngectomy (TPL) is increasingly used as a salvage procedure after failure of conservative treatments [3, 4]. Docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil (TPF)-based induction chemotherapy (ICT) followed by radiotherapy (RT, more or less CT) in good responders or definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) are two well-validated strategies for larynx preservation in patients with hypopharynx/larynx cancer who are candidates for TPL [4, 5]. In Europe, and particularly in France, ICT-based protocols tend to be preferred to CRT, unlike in the United States where CRT remains the standard for avoiding TPL.

Oncologic and functional results of therapy in patients with locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer have been recently reported in several laryngeal preservation clinical trials [5, 7]. These results are difficult to transpose into daily clinical practice because patients included in clinical trials are highly selected based on their age, PS (performance status) and comorbidities. Furthermore, the results of larynx-preservation protocols in patients with hypopharyngeal cancer are insufficiently documented because most laryngeal preservation clinical trials have included a majority of patients with laryngeal cancer.

The objectives of the present study were to evaluate oncologic and functional outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer included in an ICT-based larynx preservation program in daily clinical practice.

Materials and methods

All patients with locally advanced (T3/4, N0–3, M0) hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, technically suitable for TPL, treated by TPF-ICT for larynx preservation at our institution between June 2004 and June 2013 were included in this retrospective study. An informed written consent was required to participate in this study and the protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of our institution. Patients received 2–3 cycles of TPF (docetaxel 75 mg/m2 on day 1, cisplatin 75 mg/m2 on day 1, and fluorouracil 750 mg/m2 per day on days 1 through 5) at 3-week intervals. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was administered prophylactically (one subcutaneous injection of pegfilgrastim per ICT cycle), but we did not use prophylactic antibiotics during ICT. Two weeks after the second or third treatment cycle, patients underwent endoscopy under general anesthesia and a CT-scan of the neck and chest. Patients with complete response to ICT after 2 cycles did not receive the third cycle of ICT. The third cycle of ICT was optional and was used in cases of partial response to ICT to improve the response and only if the tolerance of ICT was satisfactory. Good responders to induction chemotherapy (at least 50 % regression of their primary tumor volume evaluated by both CT-scan and endoscopy and/or recovery of larynx mobility) received conventional external beam RT (one 2-Gy fraction per day 5 days per week for a total of 70 Gy), more or less cisplatin (3 cycles of 100 mg/m2 cisplatin per day on days 1, 22, and 43 of RT) or cetuximab (loading dose of cetuximab 400 mg/m2 on day 1 of the week preceding RT and, thereafter, a weekly dose of 250 mg/m2 during RT). Poor responders to induction chemotherapy underwent immediate TPL (median time between tumor response assessment and TPL = 22 days).

General health status was determined by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score and the WHO performance status (PS). Patients were staged according to the 2009 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system. Post-therapeutic clinical examinations of the patients were scheduled every 2 months during the first 2 years, then every 4 months. Signs of local, regional or distant recurrence of the tumor were sought at each consultation. A head and neck computed tomography scan and a thoracic computed tomography scan were performed 3–4 months after the end of treatment, every year for 2 years, then in cases of clinical suspicion of recurrent disease. Overall survival (OS), cause-specific survival (SS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were determined by Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Swallowing was evaluated using the “Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale” (DOSS) [8]. This well-standardized scale is used to classify the ability to swallow in 7 steps as follows: level 7: normal diet in all situations; level 6: normal diet within functional limits/modified independence; level 5: modified diet, mild dysphagia, distant supervision, may need one diet consistency restricted; level 4: modified diet, mild-moderate dysphagia, intermittent supervision/cueing, one or two consistencies restricted; level 3: modified diet, moderate dysphagia, total assistance, supervision, or strategies, two or more diet consistencies restricted; level 2: non-oral nutrition necessary, moderately severe dysphagia, maximum assistance or use of strategies with partial per-oral nutrition only; level 1: severe dysphagia, unable to tolerate any per-oral nutrition safely.

The presented functional outcome (DOSS, permanent enteral nutrition) corresponds to the results reported at the follow-up visit scheduled 6 months after the end of treatment. Patients who died or presented a tumor recurrence in the first 6 months after the end of treatment were not evaluated for dysphagia. We determined the laryngeal function preservation rate as defined by the proportion of patients without TPL, tracheotomy or enteral tube-feeding.

The impact of the following factors: patient age (< vs ≥60 years), gender, ASA score (< vs ≥3), PS (0 vs 1), weight loss (< vs ≥10 % of body weight), body mass index (BMI), alcohol abuse, tobacco consumption, T stage (T3 vs T4), N stage (< vs ≥1 and < vs ≥2), response to ICT (< vs ≥50 %) on oncologic (OS, SS, and LRC) and functional (DOSS ≥6, permanent enteral nutrition, larynx preservation, i.e. no TPL) outcomes was investigated by univariate and multivariate analysis. For oncologic outcomes, statistical analyses were performed using log rank tests. All variables associated with p < 0.10 on univariate analyses were included in Cox regression models. For functional outcomes, statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t tests for BMI and Chi squared tests for the other factors. All variables associated with p < 0.10 on univariate analyses were included in logistic regression models. All statistical tests were performed with the R.2.10.1 software program for Windows, with a threshold of significance of 5 %.

Results

A total of 53 patients, 42 men and 11 women, mean age 58.6 ± 8.2 years (from 31 to 80 years), were included in the present study. Their main clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Therapeutic management and oncologic outcomes

Two patients received only 1 cycle of ICT due to severe toxicities. Twenty-four patients received two cycles of ICT and 27 patients received three cycles of ICT. Two patients died during the ICT period (1 patient after 1 cycle and 1 patient after 2 cycles of ICT). The cause of these two deaths remains unknown (patients died at home without identified severe ICT toxicity). Consequently, fifty patients were evaluable for response to ICT. Partial response (≥50 % decrease in primary tumor volume) was experienced by 45 patients (90 %) including 18 (36 %) cases of complete response. Among the 44 patients with unilateral larynx fixation before therapy evaluable for tumor response, 31 (70 %) recovered larynx mobility after ICT. The nodal response to ICT was evaluable in 36 patients (37 patients were classified as N ≥ 1). There were 27 (75 %) partial nodal responses to ICT including 8 (22 %) cases of complete response. Apart from the 2 patients who died during ICT, 17 patients (32 %) experienced some grade 3–4 toxicity, in particular, febrile neutropenia (n = 4), renal toxicity (n = 3) and mucositis (n = 3). The rate of grade 3–4 toxicity in patients who received 2 or 3 cycles of ICT was 50 % (12/24) and 19 % (5/27), respectively.

Of the 50 evaluable patients after ICT, 5 were poor responders (<50 % decrease in primary tumor volume without larynx remobilization) and were offered immediate radical surgery (3 refused and received chemoradiotherapy, 2 underwent TPL). Among the 45 responders to ICT, 34 received RT+cisplatin or carboplatin, 5 received RT+cetuximab and 6 received RT alone. One patient who received only one cycle of ICT due to toxicity received RT+cisplatin.

During RT (RT alone or with carboplatin, cisplatin or cetuximab), 27 patients experienced some grade 3–4 toxicity, including mucositis (n = 9), renal toxicity (n = 7), anemia, thrombopenia or neutropenia (n = 6) and dermatitis (n = 5). The rate of grade 3–4 toxicity in patients who received RT alone, RT+cetuximab or RT+cisplatin/carboplatin was 29 % (2/7, 2 cases of mucositis), 71 % (5/7, including 4 dermatitis), and 54 % (20/37, including 6 renal toxicity and 6 mucositis), respectively.

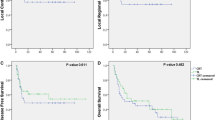

Median follow-up was 41 months (95 % CI 37–67 months). At the time of our evaluation, 18 patients had died, 16 from their cancer and 2 from another disease. Kaplan–Meier survival curves for OS, SS and RFS are shown in Fig. 1. Detailed oncologic outcomes (OS, SS and RFS rates) are shown in Table 2. Tumor recurrence was observed in 18 patients. The three most frequent recurrence modalities were: (1) isolated local recurrence (n = 6), (2) local and regional recurrence (n = 6), (3) regional and metastatic recurrence (n = 3). Apart from the two non-responders to ICT who underwent immediate TPL, eight patients underwent salvage TPL for local (±regional) tumor recurrence after non-surgical initial therapy.

Functional outcomes

Enteral nutrition was required in 17 patients (32 %) and was initiated before therapy in three cases, during ICT in six cases, during surgery in one case (TPL in a poor responder to ICT) and during RT in seven cases. Four (8 %) patients required definitive enteral nutrition. For the 13 other patients, the mean duration of enteral nutrition was 14.8 ± 11.1 months. Forty-eight patients were evaluable for dysphagia. The mean DOSS score was 5.3 ± 1.6. At the time of functional evaluation, 28 patients had recovered a normal diet (DOSS level 6 and 7). No patients required tracheotomy for persistent larynx obstruction after larynx preservation therapy. At the time of this study, 10 patients had undergone TPL. The number of patients who were alive, disease-free and with a functional larynx at 2 years was 31 (58 % of the 53 patients).

Prognostic factors of oncologic and functional outcomes

Prognostic factors of oncologic and functional outcomes are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

T stage (T4) and response to ICT (<50 %) were independent pejorative prognostic factors of OS (T4: OR 4.49, 95 % CI 1.52–13.25; response ≥50 %: OR 0.22, 95 % CI 0.06–0.80) and RFS (T4: OR 5.06, 95 % CI 1.55–16.49; response ≥50 %: OR 0.22, 95 % CI 0.06–0.72). BMI before therapy and response to ICT (<50 %) were independent pejorative prognostic factors of SS (BMI: OR 0.78, 95 % CI 0.63–0.98; response ≥50 %: OR 0.24, 95 % CI 0.06–0.88).

Response to ICT (<50 %) was the only independent predictive factor of poor functional outcomes (DOSS, permanent enteral nutrition, larynx preservation).

Discussion

Patients with locally advanced hypopharynx cancer suitable for TPL are managed as often as possible in a larynx-preservation program [1, 2, 4]. Two main approaches to larynx preservation have been evaluated: induction CT followed by RT in good responders to induction CT and concurrent RT+CT [4]. However, primary TPL remains the first therapeutic option in patients with macroscopic thyroid/cricoid cartilage invasion (T4) or with contraindication to CT [3, 4]. In Europe, and particularly in France, induction CT-based protocols tend to be preferred to concurrent RT+CT [4–6]. Several randomized phase III studies have established the docetaxel-cisplatin-fluorouracil (TPF) regimen as the gold standard of induction CT in patients with stage III–IV head and neck cancer [5, 7]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the TPF regimen provides a significantly higher larynx preservation rate, with no difference in OS compared with PF alone [5, 7].

Larynx preservation trials were generally based on careful patient selection and included a large majority of patients with laryngeal cancer [4–7]. Therefore, results of such studies, and particularly regarding patients with hypopharyngeal cancer, have to be transposed into daily practice with caution. In our institution, TPF-ICT followed by RT ± CT in good responders was the preferred modality of larynx preservation. It is not recommended to include patients with large T4 tumors in a larynx preservation program [4]. However, in clinical practice, a significant proportion of patients refuse radical surgery as the primary modality of treatment, and conservative non-surgical treatments are sometimes offered to young patients with small extra-laryngeal tumor extension. Therefore, in this series, a small proportion (17 %) of patients with T4-hypopharyngeal cancer had been included in a larynx preservation program. The results of the present study show that T4 tumor stage was the main pejorative prognostic factor. This corroborates the international consensus regarding larynx preservation protocols that recommend radical surgery as initial treatment for T4 lesions [4]. In recent larynx preservation clinical trials, response to ICT ≥50 % along with larynx remobilization were required to avoid TPL [4–6]. Interestingly, in this series, response to ICT was the second most important prognostic factor and was the only predictive factor of larynx preservation. Taken together, all these results suggest that patients who are inadequately treated with larynx preservation protocols instead of radical surgery are exposed to a higher risk of death and, finally, little chance of organ preservation. This is of particular importance on account of the current controversy about a possible deleterious impact on the survival of hypopharynx/larynx cancer patients due to the implementation of larynx preservation protocols outside clinical trials [4].

Safety and efficacy of TPF-ICT in this study were comparable to those reported in recent clinical trials [4–7]. Indeed, in the TREMPLIN phase II study, 23.5 % of patients experienced some grade 3–4 toxicity during ICT in comparison to 32 % in the present study and 15 % were poor responders to ICT in comparison to 10 % in the present study [6]. Therefore, the results of the present study suggest that, in daily clinical practice, TPF-ICT can be used for larynx preservation in patients with locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer, with satisfactory results in terms of tolerance and early efficacy. Moreover, similarly to the TREMPLIN study, we showed that during RT, mucositis and renal dysfunction were the main grade 3–4 toxicities observed in patients who received cisplatin or carboplatin whereas dermatitis was the most common toxicity encountered in patients who received cetuximab [6]. In clinical practice, the treatment associated with radiotherapy after ICT depends on the response and tolerance to ICT. Today, the protocol that can best compare with RT alone after ICT is still to be determined [6].

Oncologic outcomes reported in the present study were satisfactory in comparison to most published studies. Indeed, at 5 years, we found OS, SS and RFS rates of 56, 60 and 54 %, respectively. In the EORTC trial 24891, Lefebvre et al. reported 5-year OS and RFS rates of 38 and 31.7 %, respectively, for patients treated by PF-ICT followed by RT alone [9]. The better oncologic outcomes reported in the present study could probably be attributed to the addition of docetaxel to the ICT regimen, while several randomized phase III studies have established the TPF regimen to be the gold standard of ICT [4, 5, 7, 10]. In a series of 33 patients treated by concurrent RT+CT for locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer, Huang et al. found OS, SS and RFS rates of 44, 56 and 41 %, respectively [11].

In the TREMPLIN study, a composite end point, laryngoesophageal dysfunction-free survival (which included death, local relapse, laryngectomy, tracheotomy, and/or feeding tube at 2 years or later) was introduced after the study was designed [6]. No difference was detected in this end point between the two arms of treatment 2 years after random assignment: 79 % for the RT+cisplatin arm versus 72 % for the RT+cetuximab arm. In the present study, we found a laryngoesophageal dysfunction-free survival at 2 years of 58 %. This result, slightly lower than the results of the TREMPLIN study, could be mainly explained by the inclusion of approximately 40 % of patients with laryngeal cancer in the TREMPLIN study, resulting in better oncologic outcomes (OS rates at 3 years of 75 % for the cisplatin arm and 73 % for the cetuximab arm, compared to 67 % in the present study). Regarding specifically laryngoesophageal dysfunction, in the present study we found no cases of tracheotomy and only 2 cases of feeding tube dependence at 2 years or later. Finally, laryngoesophageal dysfunction, defined as the need for tracheotomy or feeding tube, is a relatively rare event after TPF-ICT-based larynx preservation protocols, and cancer-related deaths as well as local recurrence requiring TPL are the main events impacting laryngoesophageal dysfunction-free survival.

Interestingly, response to ICT, which was one of the main prognostic factors of oncologic outcomes, was also the main predictor of functional results. Indeed, after multivariate analyses, response to ICT <50 % was associated with a poorer DOSS score and a higher risk of permanent enteral nutrition. In this study, we observed 32 % of the patients requiring enteral nutrition but only 8 % of patients needing definitive enteral nutrition. In this regard, in a recent study assessing gastrostomy tube placement in patients with hypopharyngeal cancer treated with RT or RT+CT, Bhayani et al. showed that 70 % of patients required gastrostomy tube placement and that 28 % of patients maintained a gastrostomy tube at 1-year follow-up [12]. Rates of enteral nutrition during therapy are difficult to compare between studies because these rates depend largely on the nutritional support policy of each institution during head and neck cancer treatment. Indeed, some centers place feeding tubes prophylactically in all patients before treatment, while others elect to wait until feeding tube placement is clinically indicated [13, 14]. However, the relatively low rate of enteral nutrition during therapy observed in the present study could be explained, at least in part, by the rapid functional improvement produced by ICT in good responders. This rapid functional recovery, associated with the antitumor effect of ICT which can be obtained before radiation therapy, is one of the potential benefits of ICT in comparison to concurrent RT+CT in the context of larynx preservation strategies.

Conclusion

We can conclude from the results of the present study that a TPF-ICT-based larynx preservation protocol can be used in daily clinical practice for patients with locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer with satisfactory results in terms of tolerance and efficacy, and produced oncologic and functional outcomes comparable to those reported in recent larynx-preservation clinical trials. T4 tumor stage and poor response to ICT were the main predictors of worse oncologic and functional results, confirming that radical surgery remains the most appropriate treatment for tumors with large cartilaginous invasion or in cases of poor response to ICT.

References

Hirano S, Tateya I, Kitamura M et al (2010) Ten years single institutional experience of treatment for advanced hypopharyngeal cancer in Kyoto University. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 563:56–61

Takes RP, Strojan P, Silver CE et al (2012) Current trends in initial management of hypopharyngeal cancer: the declining use of open surgery. Head Neck 34:270–281

Agopian B, Dassonville O, Chamorey E et al (2011) Total pharyngolaryngectomy in the 21st century: indications, oncologic and functional outcomes. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 132:209–214

Lefebvre JL, Ang KK (2009) Larynx Preservation Consensus Panel. Larynx preservation clinical trial design: key issues and recommendations-a consensus panel summary. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 73:1293–1303

Pointreau Y, Garaud P, Chapet S et al (2009) Randomized trial of induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with or without docetaxel for larynx preservation. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:498–506

Lefebvre JL, Pointreau Y, Rolland F et al (2013) Induction chemotherapy followed by either chemoradiotherapy or bioradiotherapy for larynx preservation: the TREMPLIN randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol 31:853–859

Posner MR, Norris CM, Wirth LJ et al (2009) Sequential therapy for the locally advanced larynx and hypopharynx cancer subgroup in TAX 324: survival, surgery, and organ preservation. Ann Oncol 20:921–927

O’Neil KH, Purdy M, Falk J et al (1999) The dysphagia outcome and severity scale. Dysphagia 14:139–145

Lefebvre JL, Andry G, Chevalier D, EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Group et al (2012) Laryngeal preservation with induction chemotherapy for hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: 10-year results of EORTC trial 24891. Ann Oncol 23:2708–2714

Vermorken JB, Remenar E, van Herpen C, EORTC 24971/TAX 323 Study Group et al (2007) Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 357:1695–1704

Huang WY, Jen YM, Chen CM et al (2010) Intensity modulated radiotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy for larynx preservation of advanced resectable hypopharyngeal cancer. Radiat Oncol 5:37–44

Bhayani MK, Hutcheson KA, Barringer DA et al (2013) Gastrostomy tube placement in patients with hypopharyngeal cancer treated with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy: factors affecting placement and dependence. Head Neck 35:1641–1646

Ravasco P (2011) Nutritional support in head and neck cancer: how and why? Anticancer Drugs 22:639–646

Atasoy BM, Yonal O, Demirel B et al (2012) The impact of early percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement on treatment completeness and nutritional status in locally advanced head and neck cancer patients receiving chemoradiotherapy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 269:275–282

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bozec, A., Benezery, K., Ettaiche, M. et al. Induction chemotherapy-based larynx preservation program for locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer: oncologic and functional outcomes and prognostic factors. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273, 3299–3306 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-016-3919-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-016-3919-3